Abstract

Research indicates that social influences impact college alcohol consumption. However, little work has addressed how selection processes may serve as an influential factor predicting alcohol use in this population. A model of influence and selection processes contributing to alcohol use across the transition to college was examined using structural equation modeling among a sample of late adolescents (N=193). Results indicate selection processes occur as students transition into college and have the opportunity to seek out and join new friend circles, while peer influence occurs once students have settled within a circle of friends at college. Implications for prevention are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Rarely does alcohol consumption occur before early adolescence (Maggs & Schulenberg, 2005). Within a few years however, alcohol use and misuse escalate to lifetime peaks (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2001; Schulenberg et al., 1996). Alcohol is the most commonly used drug among American adolescents (Callas, Flynn, & Worden, 2004). Approximately 3 out of every 10 American adolescents experience problems related to alcohol use and about 1 out of every 15 adolescents will eventually become dependent upon alcohol (Martin et al., 1995). As documented in a national survey, 69% of eighth graders and 88% of twelfth graders have tried alcohol; these rates are higher among adolescents who transition into college (Epstein, Botvin, Diaz, & Schinke, 1995; Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2005; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002).

For many adolescents, age-related contextual changes such as transitioning into college bring about more personal freedom, and an increasing amount of time is spent with peers (Bagozzi & Lee, 2002; Borsari & Carey, 2001; Wood, Read, Palfai, & Stevenson, 2001). During peer interactions, adolescents construct perceptions of normative behaviors and attitudes (social norms) for that group; these perceptions may influence individual behavior and attitudes (Bagozzi & Lee, 2002; Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Wood et al., 2001). There are two distinct categories of social norms that exist within the literature which refer to two different types of perceptions (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallegren, 1990; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004). The first type, injunctive norms, refers to one's perceptions of the extent to which others approve or disapprove of a particular behavior. The second type of social norms is descriptive norms. Descriptive norms refer to one's perceptions of what others actually do (e.g., how much one's closest friends drink). The current study focuses solely on descriptive norms.

The present study aims to integrate two relatively disparate yet related fields of inquiry regarding engagement in alcohol use and misuse during the transition to college, namely research on social influences and peer selection. Although a number of studies have examined selection and influence processes as explanations for the origin of behavioral and attitudinal similarities between adolescents and their peers in middle and high school (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Epstein et al., 1995; Fisher & Bauman, 1988; Kandel, 1978), there is surprisingly little empirical research investigating these constructs as they work simultaneously to establish patterns of alcohol consumption among college populations. A model is proposed in which normative perceptions of peer alcohol use and self-reports of drinking behavior assessed the summer following high school graduation predict normative perceptions of one's closest friends alcohol use and one's own drinking behavior in the first year of college. This study investigates the extent to which social influence and selection processes contribute to the construction of normative perceptions of alcohol use and actual alcohol use in college. Exploring the associations between influence, selection, and alcohol use is an important step toward identifying the antecedents of the proximal targets of alcohol interventions at the college level. The rest of the introduction will be devoted to: a) A review of the literature regarding alcohol use in college, social influence, and peer selection and b) A rationale for the examination of these constructs simultaneously.

Alcohol Use in College

The drinking style of the college population, characterized by weekend binges, is unique in comparison to their same-age non-college peers; this pattern places college students at high risk for immediate negative consequences (Baer & Carney, 1993; Dawson et al., 2004; Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005). Several studies have concluded that the overall prevalence of heavy episodic drinking (defined in these cases as consuming 5 or more drinks in a row for men and 4 or more drinks in a row for women) among college students has remained remarkably stable over the last several decades, with 40 to 45% reporting heavy drinking within a two week period (Centers for Disease Control, 1997; Johnston, O'Malley, & Bachman, 2003; Wechsler et al., 2002). At this percentage, it is clear that alcohol use and abuse in college settings has been and remains a serious public health problem, as heavy drinking in college is a contributing factor to many other problems among college students including academic impairment; psychological problems; high-risk sexual behaviors; verbal, physical, and sexual violence; personal injuries or death; property damage; and legal costs (Hingson et al., 2005; Larimer, Irvine, Kilmer, & Marlatt, 1997; Read et al., 2002; Sher, Bartholow, & Nanda, 2001; Wechsler et al., 2002).

Social Influence

Substance use among adolescents has been attributed to an interaction between multiple influences (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). The factors influencing alcohol misuse in college can be grouped into four major categories: individual factors, ecological factors, parental influences, and peer influences (Baer, 2002; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992). Peer influences in relation to alcohol use in college are typically discussed in the form of affiliation with alcohol-using peers, peer modeling of drinking behavior, perceived peer norms of alcohol consumption, and perceived prevalence of adolescent alcohol use (Baer & Carney, 1993; Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991; Larimer & Neighbors, 2003; Read et al., 2002). Social influence, in the form of peer influence, is a particularly strong and proximal predictor of college aged alcohol use and abuse and is the focus of the present study (Callas et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2001).

Social learning theory (SLT) specifies the processes by which social influences, such as perceived norms, may contribute to drinking behavior in college populations (Larimer et al., 1997; Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005; Wood et al., 2001). SLT in the context of adolescent substance use focuses on the source of substance-specific beliefs and related behaviors (Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, & Radosevich, 1979; Bandura, 1977). Specifically, SLT posits that adolescents obtain their substance-specific attitudes and beliefs from influential role models such as their parents and peers (Bandura, 1977, 1982). SLT hypothesizes that (1) adolescents come to form their substance-specific attitudes and beliefs through observation of role models, (2) adolescents imitate the observed behaviors, (3) the behavior is socially reinforced, and (4) as a result of social reinforcement, expectations for positive consequences develop (Akers et al., 1979; Bandura, 1977; Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005). Based on SLT, Scheier and Botvin (1997) suggested that the single most important reason adolescents drink is the need for social approval by their immediate peers, as they are noted as the predominant influence during this developmental period (Bagozzi & Lee, 2002; Borsari & Carey, 2001; Wood et al., 2001). Perceived peer norms refer to judgments people make about the acceptability and typicality of various peer behaviors (Borsari & Carey, 2001). The assessment of perceived peer norms in alcohol research represents an attempt to measure an individual's understanding of the social tone, level of acceptance, and prevalence of drinking behavior among peers (Baer, 2002; Graham, Marks, & Hanson, 1991; Thombs, Olds, & Ray-Tomasek, 2001). Research indicates that individuals who perceive alcohol use to be more prevalent and acceptable, that is, those who report greater perceived norms, show greater alcohol use and misuse themselves (Baer et al., 1991; Sher, Bartholow, & Nanda, 2001; Thombs et al., 2004).

Peer Selection

Generally neglected in research on college students’ substance use is the examination of the origin of behavioral similarity among individuals and their peers. In research with early and middle adolescents, in contrast, peer group similarity or homogeneity has been found to be a result of both influence and peer selection processes (Chassin et al., 1986; Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Sieving, Perry, & Williams, 2000; Wills & Cleary, 1999). Peer selection refers to a mechanism whereby observed similarities between peers are the result of individuals choosing and keeping friends based on whether their beliefs and behaviors are similar to their own (Kandel, 1978). Unlike processes of peer influence, where the direction of effect is assumed to flow from the peer to the individual, peer selection is a process in which the direction of the effect is assumed to originate within the individual (Fisher & Bauman, 1988). The integration of research involving both processes of influence and selection at the college level would lend to a more complete understanding of the mechanisms through which college students choose to use and/or misuse alcohol.

Influence, Selection, and Alcohol Use in College

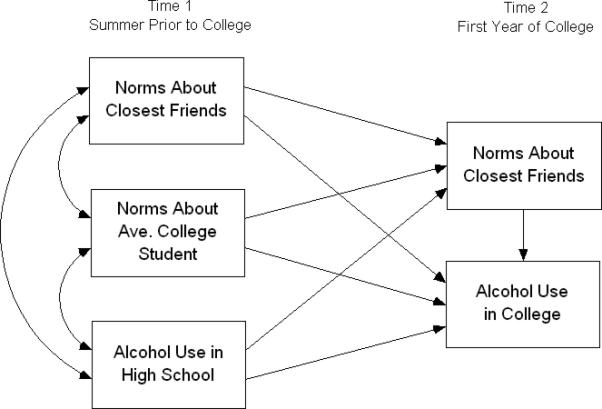

The importance of examining influence and selection simultaneously is supported by theoretical literatures purporting the interaction of active organisms and active environments in developmental processes (Lerner, 1982; Rutter, 1996; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). This framework assumes that individuals play a role in their own development. In the present study, the perceived drinking norms about the average college student, as held before entering college, as well as the perceived drinking norms about one's high school friends and individual high school alcohol use may influence students during their first year of college to selectively and differentially expose themselves to various developmental opportunities and peer groups, where in turn, new friend norms are formed and reinforced (Scarr, 1992; Shanahan, Sulloway, & Hofer, 2000; Zirkel, 1992). As such, since research on peer selection refers to a phenomenon where similarities between peers are due to individuals choosing friends based on whether their beliefs and behaviors are similar to their own (Fisher & Bauman, 1988; Kandel, 1978), the current study proposes that students entering college will first seek out new friends who drinking behavior is thought to be similar to their own prior drinking behavior. Additionally, as research on social influence suggests that the single most important reason adolescents drink is the need for social approval by their immediate peers (Scheier and Botvin, 1997), we hypothesize that upon settling into college and establishing new friend networks, a new set of friend norms will be formed which have the potential to influence drinking behavior during college. An illustration of this hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1. An examination of these processes of influence and selection simultaneously, particularly across this developmental transition into college, may help to shed light on appropriate or successful timing and targets for interventions designed to reduce the onset and extent of young adult alcohol misuse.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Model Predicting Drinking Norms and Alcohol Use Across the Transition to College

The present study examines processes of selection and influence in the prediction of perceived drinking norms and alcohol use across the transition to college in order to address two primary research questions. (1) Do perceived drinking norms about the average college student before one has entered college influence one's close friend drinking norms and own drinking in college? (2) Do close friend drinking norms and own drinking prior to college impact college friend drinking norms and, in turn, one's own alcohol use? Also, as past peer influence research has indicated, it is expected that college friend drinking norms will be highly associated with individual drinking in college.

METHOD

Sample and Procedure

The University Life Transitions (ULTRA) Project utilized a two-wave design. Incoming first-year students (M= 18.99 years, SD = .50) at a large public university in the Southwest United States were invited to complete surveys as part of free, entertainment-oriented health promotion sessions put on by the university's Campus Health. Data collection followed a dinner the night before 2-day mandatory college orientation sessions during the summer prior to students’ first year at university (Time 1; N = 943). The response rate at Time 1 was high (98%). Incentives at Time 1 were t-shirts and entry into raffles for $20. About half (51.4%) of the Time 1 sample were women and the majority (82.8%) were White, with 6.5% Hispanic, 4.1% Multicultural, 3.8% Asian American, 1.9% African American, 0.5% Native American, and 0.2% International students.

A targeted subsample (N=202) participated in 10 weekly telephone interviews across the following spring semester (Time 2). The 10 interviews focused on alcohol use, expectancies, and consequences. Each week a number of unique questions were asked. Participants were eligible if they (a) were first-year students (96%); (b) were under age 21 (99.8%); (c) lived on-campus (86.3%); (d) reported consuming at least one drink of alcohol during their senior year of high school (79.3%); and (e) had indicated their willingness to be contacted for follow-up (64.6%). Of the 390 who met these criteria, 342 telephone numbers were successfully identified and called. Eighty-seven were not reached (e.g., had dropped out of school). Of the 255 contacted, 202 (79.3%) agreed to participate. Of the 202 that agreed to participate, 193 provided complete data on the variables used in the current study.

Characteristics of the resulting sample of 193 cases with complete data are as follows: Participants averaged 18.26 years (SD = .5) at Time 1. All lived on campus, 53% planned to join a fraternity/sorority, 65% were female, and 83% self-identified as white, non-Hispanic. These characteristics, while not representative of college students in the US, make this group more at risk for heavy drinking, as they are young, residential, and relatively interested in the Greek system (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000).

Measures

At Time 1, established self-report measures with known psychometric properties were used. Time 2 phone interviews used similar measures, adapted and piloted for repeated oral Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) administration.

Drinking Norms About Closest Friends (Time 1)

At Time 1 (prior to college entrance), participants’ perceptions of the drinking norms of their closest friends in high school were measured by the question, “How many drinks on a typical Friday night do your closest friends drink?” Possible responses were open-ended, and ranged from 0 to 23 drinks (M = 4.91, SD = 3.51) (Baer, 1994; adapted).

Drinking Norms About the Average College Student (Time 1)

The perceived drinking norms of the average college student were measured using an item adapted from Baer (1994); “How many drinks on a typical Friday night does an average college student drink?” Possible responses were open-ended, and ranged from 0-23 drinks (M = 5.57, SD = 2.75).

Alcohol Use in High School (Time 1)

To assess the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumed during senior year of high school (Grade 12), students were asked two questions: (a) “During the past 12 months how often, on average, did you drink beer, wine, or liquor?” Possible responses for this question were: 0 = “I did not drink at all”, 1 = “less than once per month”, 2 = “once a month”, 3 = “once every two weeks”, 4 = “once a week”, 5 = “2-3 days a week”, 6 = “4-6 days a week”, or 7 = “everyday.” (b) “Think of all the times during the past 12 months when you drank beer, wine or liquor. On average, how many drinks did you have on each occasion?” Possible responses for this question were: 0 = “I did not drink at all”, 1 = “1 drink”, 2 = “2-3 drinks”, 3 = “4-6 drinks”, 4 = “7-9 drinks”, 5 = “10-12 drinks” or 6 = “more than 12 drinks.” Scores from each question were multiplied in order to obtain an estimated total of the quantity of alcohol consumed by each individual. For example, in an individual reports drinking 2-3 drinks, 2-3 days a week, their total estimated level of consumption would be 10 (2 × 5). High scores thus indicated higher total levels of drinking (Dawson, 2003). Scores ranged from 0 to 30 (M = 7.92, SD = 5.94).

Drinking Norms About Closest Friends (Time 2)

At Time 2, the perceived drinking norms about one's closest friends in college were assessed by asking, “Please estimate how much different types of college freshmen drink. Please assume you are rating a typical freshman of your same sex.”...“On a typical Friday night, how many drinks do you think your closest friends drink?” (Baer, 1994; adapted). Responses ranged from 0 to 15 drinks (M = 4.67, SD = 3.45).

Alcohol Use During the First Year in College (Time 2)

The quantity and frequency of alcohol use during the second semester of the first year of college was also assessed by asking students two questions: (a) “During the past 10 weeks, how often on average, did you drink beer, wine, or liquor?” The response format for this question was 0 = “I did not drink at all”, 1 = “less than once per month”, 2 = “once a month”, 3 = “once every two weeks”, 4 = “once a week”, 5 = “2-3 days a week”, 6 = “4-6 days a week”, and 7 = “everyday.” ; (b), “For this question, think about only those days during the past 10 weeks that you did drink alcohol. On average, on those days that you drank how many drinks did you have?” Possible responses for this item were: 0 = “I did not drink at all”, 1 = “1 drink”, 2 = “2-3 drinks”, 3 = “4-6 drinks”, 4 = “7-9 drinks”, 5 = “10-12 drinks” or 6 = “more than 12 drinks.” Similar to the measure of alcohol use at Time 1, scores from each question were multiplied in order to obtain an estimated total of the quantity of alcohol consumed by each individual (Dawson, 2003). Scores ranged from 0 to 30 (M = 9.89, SD = 6.15).

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to conducting the primary analyses, the data were examined for the presence of bias due to attrition and missing data. First, attrition analyses tested for mean-level differences between eligible individuals who at Time 1 agreed to be contacted for the Time 2 portion of the study and those who did not. Independent sample t-tests were run to examine potential differences between the three Time 1 variables of interest: alcohol use, perceived drinking norms about one's closest friends, and perceived drinking norms about the average college student. Results indicated that only the index of alcohol use differed between the two mentioned groups, such that the individuals who agreed to be contacted drank slightly less than those individuals who did not agree to be contacted, Mean difference in score = 1.5 [SD = .58], t (736) = -2.52, p < .05. There were no differences in the perceived drinking norms of high school friends or of the average college student, nor were there any demographic differences between individuals who agreed to participate and those that did not; that is, gender, ethnicity, and self-reported high school GPA were not significantly different from each other (p's > .05).

Second, an examination of the Time 1 and Time 2 data was conducted to check for the presence of missing data due to participants skipping questions. Results revealed slightly less than 1% of the data was missing; a missing data analysis was run in SPSS utilizing the EM algorithm for data imputation. In short, the EM procedure examines the data case by case, and in the event of missing data imputes the predicted value based on all other variables in the data set (Graham & Donaldson, 1993; Little & Rubin, 1987). The imputed score is the expected value of a regression equation using all other variables of interest as predictors as well as a correction term. As the percent of missingness was less than 1% of the data, single imputation has been shown as an acceptable method with negligible biasing effects (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Analyses were performed using this imputed data set.

Third, correlations, means, standard deviations, ranges, and skewness statistics were run in order to test for the variability and normality of the variables in the model (see Table 1). The skewness statistics were within the acceptable range of -2 to 2 (< 1.70), such that no transformations were necessary.

Table 1.

Drinking Norms and Alcohol Use Variables: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Mean | SD | Range | Skew | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Norms of Average College Student (T1) | 5.57 | 2.75 | 20 | 1.42 | ||||

| 2. Norms of Closest Friends (T1) | 4.91 | 3.50 | 23 | 1.70 | .608** | |||

| 3. Norms of Closest Friends (T2) | 4.67 | 3.45 | 22 | 1.52 | .245** | .457** | ||

| 4. Alcohol Use in High School (T1) | 7.90 | 5.94 | 30 | 1.04 | .387** | .656** | .385** | |

| 5. Alcohol Use in College (T2) | 9.89 | 6.15 | 30 | .43 | .257** | .449** | .563** | .543** |

N = 193. T1 = Time 1, High School. T2 = Time 2, College.

p < .01.

RESULTS

Analysis of the Hypothesized Model

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to assess the fit of the hypothesized model presented in Figure 1. Global fit indices examined the fit of the hypothesized model to the observed patterns of relationships in the data, local fit indices (standardized path coefficients) tested the significance of direct associations, and estimates of indirect effects evaluated the significance of associations through mediating variables. A series of models were examined, beginning with a saturated structure and subsequently deleting non-significant pathways. The deletions of pathways seen in the hypothesized model represent failures to confirm the hypotheses associated with the respective pathway.

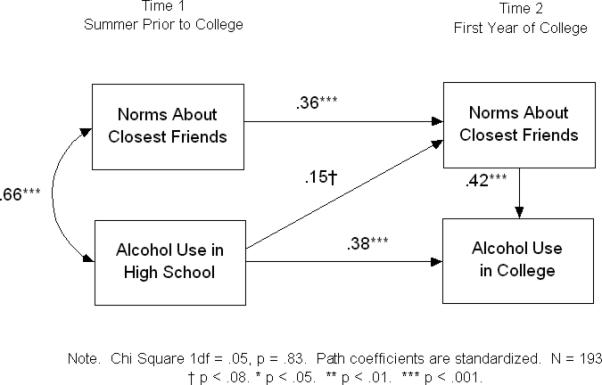

The retained model fit the observed data well, χ2 (1) = .05 , p = .83, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (see Figure 2). Processes of selection were examined via two direct effects on the perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2. The perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 1 significantly predicted perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2, b = .36, p < .001. The effect of alcohol use at Time 1 on perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2 also approached significance, b = .15, p < .08. The perceived drinking norms of the average college student at Time 1 did not significantly predict the perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2 or alcohol use at Time 2. As such, perceived drinking norms of the average college student at Time 1 were dropped from the model in order to provide clarity and brevity in the retained model.

Figure 2.

Final Model Predicting Drinking Norms and Alcohol Use Across the Transition to College

Influence was examined via the direct effect of perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2 on the reported alcohol use at Time 2. A positive and significant association was found, such that higher levels of perceived alcohol use of one's closest friends predicted higher levels of personal alcohol use, b = .42, p < .001. In addition, alcohol use at Time 1 predicted alcohol use at Time 2, b = .38, p < .001. This later relationship is indicative of moderate stability of alcohol use across the transition to college for those students who drank alcohol in high school.

In addition, the indirect effects of this model were examined. A marginally significant indirect effect was seen for perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 1 on alcohol use at Time 2 by way of the perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends in college, b = .15, p < .08. The indirect effect of alcohol use at Time 1 on alcohol use at Time 2 through perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 2 was not significant, b = .06, p > .10.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the extent to which processes of selection and social influence contributed to the construction of perceived drinking norms and actual alcohol use in college. Selection processes were believed to occur as students transitioned into college and had the opportunity to seek out and join new friend circles, and peer influence was thought to occur once students had settled within a circle of friends in college. Perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends and alcohol use assessed prior to college entrance predicted perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends during the first year of college, which in turn predicted actual alcohol use in college. The first path supports the notion that students are selecting into a college peer group that is similar to the characteristics of their previous peer group and own use. The second mentioned path is evidence of influence, as once students are in a circle of friends at college, the habits of those friends may impact individual drinking habits as well. It is important to note that only the perceived drinking norms of one's closest friends at Time 1 displayed a positive and significant relationship with the norms of one's closest friends at Time 2. The perceived drinking norms of the average college student did not predict later friend norms. This suggests that influence is not occurring across the transition to college, as students are not choosing friends based on what they perceive college students to be like, rather they appear to be choosing friends who are similar to them. Results also revealed a positive path from alcohol use in the senior year of high school to the drinking norms of one's closest friends in college, which further supports the notion that students may be selecting into groups based on similarity to their own characteristics.

Selection Processes

Findings provide some support for the hypothesized process of selection. Results indicated moderate stability across the transition from high school to college in perceptions of the drinking behavior of one's closest friends. To the extent that students develop new close friendships between the summer after high school graduation and second semester of their first year, this stability in perceptions is consistent with peer selection research which posits that, in regard to substance use among adolescent populations, substance users are more likely to choose other substance users as their friends, whereas non-users will typically choose other non-users (Ennett & Bauman, 1994).

A selection process is also echoed in the positive path between reported alcohol use in high school and the normative perception of one's closest friends in college. Consistent with previous research on selection, the normative perceptions of alcohol use of one's closest friends in college appears to be the result, at least in part, of individuals forming relationships with new friends (and eventually establishing new norms, consistent with influence as discussed in the next section) based on their perceived similarity in alcohol use and alcohol using peers (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Fisher & Bauman, 1988; Kandel, 1978).

Influence Processes

Results from this study are also consistent with processes of influence as described by Social Learning Theory which posits that influence works through the behaviors and attitudes of a potentially influential source (peers) which, in turn, impacts individual behavior (Bandura, 1977; Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005). The normative perceptions of one's closest friends predicted one's drinking in college, such that the more an individual perceived his/her friends as drinking in college, the more he/she drank. However, in the present study, it appears that an individual's drinking behavior was largely predicted by the perceived drinking behavior of his/her closest friends, whereas in past research, norms of the average student have also been linked with individual alcohol use (Larimer et al., 1997; Read et al., 2005; Thombs et al., 2001). These findings suggest that the norms of one's closest friends may be more powerful sources of influence than average student norms and should be more consistently examined in norms literature.

The Relationship between Selection and Influence

In order to examine processes of selection and influence together, the indirect pathways of this model were examined. Closest friend norms as assessed in high school indirectly predicted actual drinking in college through closest friend norms in college. Practically speaking, the evidence from this indirect pathway suggests that processes of selection are influencing later behavior, and should therefore be taken into consideration when designing alcohol misuse interventions targeting normative perceptions across the transition to college.

In comparison to previous work examining alcohol misuse across the transition to college, where normative perceptions are viewed solely as predictors of behavior (Nagoshi, 1999; Thombs, 2000; Wood et al., 2001), the present model attempts to explore issues of process, examining how both selection and influence might work to predict drinking behavior across the transition to college. Although this design is not sufficiently complex to draw strong conclusions about the ideal timing and focus of alcohol interventions, findings from this study would suggest that the targeted process of an intervention should vary across time. During high school for example, it may be more effective to focus on whom individuals become friends with and how much alcohol they drink, as this study indicates that past use and past friends are strong predictors of future use and future friends. Across the transition to college, it is possible that targeting normative perceptions may be more effective if norms of one's closest friends are also taken into consideration in addition to the perceived norms of the average college student, as this study has concluded that norms of one's closest friends in high school are positively related to later friend norms and later drinking. It is possible that accounting for multiple processes (selection and influence) may enhance effectiveness of an intervention over time (Greenberg, 2004).

Limitations

There were three limitations to note in this study. First, sample characteristics serve to potentially limit the generalizability of the present results. The sample was from only one post-secondary institution, and was predominately White (83%), female (65%), and Greek (53% planned to join). Based on eligibility criteria for participation, 100 percent were alcohol using. Although these sample characteristics are representative of individuals at risk for heavy drinking (Wechsler et al., 2000), this sample does not adequately reflect the general college population, and does not lend itself well to the examination of group differences between diverse demographic backgrounds.

A second limitation is the availability of only two points of measurement. Measuring norms of the average college student multiple times beginning in high school and across the college years would provide more fine-grained information about how these perceptions evolve over this transitional period. Additionally, the cross sectional piece of this study examining the relationship between normative beliefs and alcohol use at Time 2 would have been more compelling had alcohol use been measured at an additional time point.

Third, it is possible that the relationship between closest friend norms at Time 1 and Time 2 is driven by participants rating the same friends at both occasions, as some individuals’ high school friends may have attended the same university. To the extent that this phenomenon occurred, selection processes may be overestimated. Future research should distinguish stable friends from new friends in order to properly measure the predictive power of selection.

Future Directions

This study tested a novel model of the simultaneous processes of selection and influence as they relate to alcohol use in the first year of college. This work has important implications for better understanding effective uses of timing and focus for interventions designed to reduce alcohol misuse and the associated negative consequences among college students.

Further analyses should examine the processes of selection and influence as they differ across between-person variables (e.g., gender, socioeconomic status, generational college status, place of residence, athletic participation, Greek affiliation). An examination of demographic variables as potential moderators of the relationships depicted in the model would direct research in knowing for which groups the notion of selection and influence processes are most powerful.

Additional consideration should be paid to the possibility of designing person-specific interventions among college populations targeting the norms of one's closest friends. Programs like the Brief Motivational Intervention (Borsari & Carey, 2005) or the motivational intervention program of Marlatt and colleagues (1998), which relate an individual's drinking behavior to college and national norms, might show more pronounced effects if the focus of the individual feedback provided was based on one's closest friends. These programs typically utilize campus mental health professionals or are administered using web-based programs and have been found to be effective at reducing alcohol misuse among college populations (Borsari & Carey, 2005; Marlatt et al., 1998; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004). It may also be possible to utilize forms of social network analysis (Ennett & Bauman, 1994; Ennett et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2006) to develop a college intervention using these closest friend norms to influence behavior rather than the norms of the average college student. This intervention technique could use perceived closest friend norms along with actual friend reports of drinking behavior in a form of motivational interviewing (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005) to decrease college drinking. Of course, to the extent that heavy drinkers have developed close friendships with other heavy drinkers, this approach may have some limitations.

The current study provides a framework for understanding the processes of selection and influence across the transition to college. Enhanced knowledge of the formation of interpersonal relationships during this period of great change can inform developmental and intervention scientists focusing on safe and healthy development during college. In addition, the current study examining both the effects of the perceived norms of the average college student and perceived norms of one's closest friends illustrates ways in which existing intervention programs and paradigms (Borsari & Carey, 2005; Marlatt et al., 1998) might be modified to improve upon previous results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R03 AA013763 to J. Maggs from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and T32 DA017629 to M. Greenberg from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

REFERENCES

- Akers RL, Krohn MD, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:636–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Carney MM. Biases in the perceptions of the consequences of alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi RP, Lee K. Multiple routes for social influence: The role of compliance, internalization, and social identity. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallegren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Callas PW, Flynn BS, Worden JK. Potentially modifiable psychosocial factors associated with alcohol use during early adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1503–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: National College Health Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 1995. MMWR. 1997;46(SS-6):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman S, Montello D, McGrew J. Changes in peer and parent influence during adolescence: Longitudinal versus cross-sectional perspectives on smoking initiation. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol Research and Health. 2003;27:18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, DuRant RH. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal or Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Diaz T, Schinke SP. The role of social factors and individual characteristics in promoting alcohol use among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:39–46. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LA, Bauman KE. Influence and selection in the friend-adolescent relationship: Findings from studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18:289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Donaldson SI. Evaluating interventions with differential attrition: The importance of nonresponse mechanisms and use of followup data. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78:119–128. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Marks G, Hansen WB. Social influence processes affecting adolescent substance use. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:291–298. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M. Current and future challenges in school-based prevention: The researcher perspective. Prevention Science. 2004;5:5–13. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013976.84939.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975-2002. Government Printing Office; Washington: 2003. (NIH Publication No. 03-5376) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2004. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2005. (NIH Publication No. 05-5726) [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Homophily, selection and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Irvine DL, Kilmer JR, Marlatt GA. College drinking and the Greek system: Examining the role of perceived norms for high-risk behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Neighbors C. Normative misperception and the impact of descriptive and injunctive norms on college student gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:235–243. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Children and adolescents as producers of their own development. Developmental Review. 1982;2:342–370. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg J. Initiation and course of alcohol use among adolescents and young adults. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2005. pp. 29–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Somers JM, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a two-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto A, Bukstein OM, Moss HB. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:672–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT. Perceived control of drinkingand other predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college students sample. Addiction Research. 1999;7:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M, Sweeting H, West P, Young R, Gordon J, Turner K. Adolescent substance use in different social and peer contexts: A social network analysis. Drugs: Education, Prevention, & Policy. 2006;13:519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Capone C. A prospective investigation of relations between social influences and alcohol involvement during the transition into college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:23–34. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Davidoff OJ, McLacken J, Campbell JF. Making the transition from high school to college: The role of alcohol-related social influences factors in student's drinking. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:53–65. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Transitions and turning points in developmental psychopathology as applied to the age span between childhood and mid-adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:603–626. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S. Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Development. 1992;63:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype-environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, Botvin GJ. Expectancies as mediators of the effects of social influences and alcohol knowledge on adolescent alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL. Moving targets: Modeling developmental trajectories of adolescent alcohol misuse, individual and peer risk factors, and intervention effects. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan JJ, Sulloway FJ, Hofer SM. Change and constancy in developmental contexts. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Nanda S. Short- and long-term effects of fraternity and sorority membership on heavy drinking: A social norms perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Perry CL, Williams CL. Do friendships change behaviors, or do behaviors change friendships? Examining paths of influence in young adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL. A test of the perceived norms model to explain drinking patterns among university student athletes. Journal of American College Health. 2000;49:75–83. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Dotterer S, Olds RS, Sharp KE, Raub CG. A close look at why one social norms campaign did not reduce student drinking. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53:61–68. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.2.61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Olds RS, Ray-Tomasek J. Adolescent perceptions of college student drinking. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2001;25:492–501. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990's: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Peer and adolescent substance use among 6th-9th graders: Latent growth analysis of influence versus selection mechanisms. Health Psychology. 1999;18:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Palfai TP, Stevenson JF. Social influence processes and college student drinking: The mediational role of alcohol outcome expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirkel S. Developing independence in a life transition: Investing the self in the concerns of the day. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:506–521. [Google Scholar]