Abstract

Objectives

To determine antibacterial activity of capuramycin analogues SQ997, SQ922, SQ641 and RKS2244 against several non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).

Methods

In vitro antibiotic activities, i.e. MIC, MBC, rate of killing and synergistic interaction with other antibiotics, were evaluated.

Results

SQ641 was the most active compound against all the NTM species studied. The MIC of SQ641 was ≤0.06–4 mg/L for Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC; n = 20), 0.125–2 mg/L for M. avium paratuberculosis (MAP; n = 9), 0.125–2 mg/L for Mycobacterium kansasii (MKN;n = 2), 0.25–1 mg/L for Mycobacterium abscessus (MAB; n = 11), 4 mg/L for Mycobacterium smegmatis (MSMG; n = 1), and 1 and 8 mg/L for Mycobacterium ulcerans (MUL; n = 1), by microdilution and agar dilution methods, respectively. SQ641 was bactericidal against NTM, with an MBC/MIC ratio of 1 to 32, and killed all mycobacteria faster than positive control drugs for each strain. In chequerboard titrations, SQ641 was synergistic with ethambutol against both MAC and MSMG, and was synergistic with streptomycin and rifabutin against MAB.

Conclusions

In vitro, SQ641 was the most potent of the capuramycin analogues against all NTM tested, both laboratory and clinical strains.

Keywords: Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis, Mycobacterium abscessus, SQ641

Introduction

Capuramycin is one of a new class of nucleoside antibiotics that target the bacterial enzyme phospho-N-acetylmuramyl-pentapeptide-translocase (translocase-1, TL-1 or MraY), an essential enzyme in peptidoglycan (PG) biosynthesis.1,2 PG is unique to bacteria, including mycobacteria, but antibiotics that inhibit its biosynthesis, such as penicillins, cephalosporins and vancomycin, are not active against mycobacteria. d-Cycloserine is the only PG-inhibiting commercially available antibiotic that is effective against mycobacterial infections.3

Capuramycin was first isolated from the spent medium of Streptomyces griseus cultures, and showed activity against mycobacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes, but no activity against Gram-negative bacteria.4 A methylated derivative of capuramycin was isolated by Sankyo (now Daiichi–Sankyo, Japan) with a similar antibiotic spectrum.5 Subsequently, Sankyo scientists synthesized several thousand capuramycin analogues to improve its antibiotic activity.6–8 SQ641 was the most active compound in this class, with good in vitro activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) strains.9

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are in the same genus as the well-known human pathogen Mtb, but have very different environmental habitats: they can be isolated from water, soil, vegetation and from other animals, and are distributed worldwide. Although many NTM species can infect humans, they generally only cause severe disease in immunocompromised individuals. NTM infections are most often seen in people with immunological defects or with pre-existing conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis and pneumoconiosis. Unlike Mtb, however, NTM are not transmissible person to person. The incidence of NTM infections is on the rise around the globe, perhaps due to increased awareness and advances in diagnostic laboratory technologies.

MAC is the most common NTM causing human disease: it causes lung infections in adults, cervical lymphadenitis in children, and disseminated disease in HIV-infected individuals.10 Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP), which is genetically closely related to MAC, causes chronic granulomatous enteritis (Johne's disease) in ruminants.11 In humans, MAP has been associated with Crohn's disease (a granulomatous colitis); however, its role in the aetiology of the disease has not been clearly established.12,13 Mycobacterium kansasii (MKN) is the second most common NTM and causes pulmonary infection resembling tuberculosis and disseminated disease in AIDS patients. MKN infections are treated with antitubercular drugs, to which the organism is quite susceptible.10 Mycobacterium abscessus (MAB), on the other hand, causes chronic lung infections, and post-traumatic and post-surgical wound infections in normal individuals, and disseminated skin infections and catheter infections in immunosuppressed individuals.10,14 MAB strains are resistant to most antitubercular drugs and susceptibility to other antibiotics is highly variable. Consequently, antibiotic susceptibility testing is recommended for all clinical isolates before initiating treatment.10 Mycobacterium ulcerans (MUL) causes indolent, progressive, necrotic lesions of the skin and underlying tissue (also known as ‘Buruli ulcer’). Although the organism is susceptible to antimycobacterial drugs, their use is secondary to surgical intervention.15

We previously analysed in vitro activities of capuramycin analogues against Mtb and identified SQ641 as the most potent analogue for this mycobacterial species.16 In the present study, we investigated in vitro activities of the most active capuramycin analogues, including SQ641, against a variety of medically important NTM.

Materials and methods

Mycobacteria

The following NTM were used in these studies: 20 human isolates of MAC strains (generously provided by Oregon State University and the University of Texas Health Center); 9 human isolates of MAP (from the University of Wisconsin); 10 clinical isolates (University of Texas Health Center) and 1 ATCC strain of MAB; 2 strains of MKN (ATCC 12478 and 35775); and 1 strain each of Mycobacterium smegmatis (MSMG; strain MC2155) and MUL (ATCC 19423). MAP strains were cultivated in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% oleic acid, albumin, dextrose and catalase (OADC) and 2 mg/L mycobactin J (Allied Monitor, Fayette, MO, USA). Other NTM, except MKN, were cultivated in 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% albumin, dextrose and catalase and 0.05% Tween 80. MKN was grown in 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% OADC and 0.05% Tween 80.

Antimicrobial agents

Capuramycin analogues were obtained from Daiichi–Sankyo. Clarithromycin was obtained from Abbott Laboratories (IL, USA), rifabutin from Adria Laboratories (OH, USA), and rifalazil from Kaneka Corp. (Japan). Cefoxitin was obtained from Spectrum Chemical Mfg Corp. (Gardena, CA, USA), and moxifloxacin was purchased from Bayer Corp. (Washington, DC, USA). Amikacin, ethambutol, rifampicin, ciprofloxacin and streptomycin were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Determination of MICs

MICs for MAC, MAB, MSMG and MKN were determined by standard microdilution in 96-well microtitre plates17 using 7H9 broth containing 0.05% Tween 80. The lowest concentration of drug causing no visible growth after 48–72 h (for rapid growers) or 2 weeks (for slow growers) at 37°C was considered to be the MIC. MICs for MUL were determined by microdilution, as described above, as well as by the agar dilution method. Agar plates were incubated at 30°C for 1 month before reading. The susceptibility of MAP strains was determined by macrobroth dilution using MGITTM ParaTB medium and the BACTECTM MGITTM 960 system (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA).18

MBC determination

MBC was determined by microdilution, wherein serial dilutions of antimicrobial agents, in triplicate, were made in 100 µL volumes in 96-well plates. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to 0.1 OD at λ = 600, diluted 1/100 and dispensed in 100 µL aliquots to all the wells, including drug-free controls. Initial cfu of the bacterial suspensions were determined by plating 10-fold dilutions on 7H11 agar plates. After 2 weeks of incubation at 37°C, MICs were recorded. From wells showing no visible growth, 100 µL volumes of the drug dilutions were cultured on 7H11 agar plates to determine the remaining cfu. The lowest concentration of the drug causing a 99.9% reduction in cfu was considered to be the MBC. For MAP, MBC was determined by plating from MGIT signal-negative tubes (MIC and higher concentrations). The subsampling was done on days 8–10 (the same day or the day after the 1% control tubes became MGIT positive). An aliquot of 0.1 mL of 10-fold dilutions was plated on 7H11 agar with mycobactin J for counting cfu. The MBC was the lowest concentration of drug showing ∼2 log reduction from the initial (day 0) cfu.

Rate of killing of MAC

1× MBC of SQ641 and clarithromycin was prepared in 10 mL of 7H9 broth in 50 mL tubes in duplicate. One-week-old MAC cultures were adjusted to 0.1 OD600 and 100 µL was dispensed to each tube. The tubes were incubated on a shaker incubator at 37°C. On days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 14, the cfu of the cultures were determined by culturing 100 µL aliquots of 10-fold dilutions on 7H11 agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 weeks before counting cfu. The mean cfu for each drug was plotted against different times.

In vitro synergy between antimicrobial agents

Synergy between drugs was determined by chequerboard titration in 96-well microtitre plates.16 One drug was diluted vertically and the second drug horizontally to get a matrix of different combinations of the two drugs. Similar dilutions of individual drugs and the drug-free medium control were included in each test plate. After the addition of mycobacterial suspensions, plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 weeks (for slow growers) and 96 h (for fast growers). From the MIC of the drugs alone and in combination, we calculated the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) and the FIC index (FICI). FIC is the MIC in combination divided by the MIC of the individual drug and FICI is the sum of the FICs of individual drugs. An FICI of ≤0.5 is considered synergistic, an FICI of >4.0 is considered antagonistic and an FICI of >0.5–4 is considered to indicate no interaction.19

Results

In vitro inhibitory activity of capuramycin analogues against NTM

NTM are heterogeneous with respect to their rate of growth, colony morphology, pigmentation, pathogenicity and drug susceptibility. Smooth transparent colony morphology is associated with increased virulence and increased resistance to antimicrobials.20 Of the two rapidly growing NTM, the MSMG MC2155 strain formed rough, flat, non-pigmented colonies, whereas the MAB strains formed non-pigmented, rough and smooth colonies. MKN strains formed rough colonies with pigmentation following exposure to light and both strains required OADC enrichment for luxuriant growth. MAC strains were more diverse with respect to colony morphology and pigmentation. All of the three commonly encountered colony types (smooth transparent, smooth opaque and rough opaque) were observed, and a few formed pinpoint colonies.

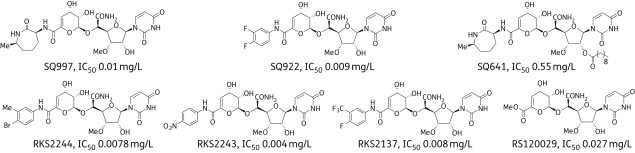

Initially, 11 different capuramycin analogues were screened for activity against four different mycobacterial species. From these, the four best analogues were selected for further investigation. Structures of the capuramycin analogues and IC50 values against TL-1 are shown in Figure 1. SQ997 is the fermentation product of S. griseus (SANK 60196). It differs from capuramycin in having a methyl group in the caprolactam ring. SQ641 is derived from SQ997 by introducing a 10-carbon lipid tail to the sugar moiety of the nucleoside. SQ922, RKS2244, RKS2137 and RKS2243 are semi-synthetic compounds bearing phenyl-type substituents instead of the caprolactam ring (Figure 1). These compounds were synthesized from RKS120029, another capuramycin metabolite, obtained by fermentation of the same strain of S. griseus in medium containing unnatural amino acids to alter the biosynthetic pathway.

Figure 1.

Structures of capuramycin analogues. IC50s = concentrations of the compounds inhibiting 50% of the activity of the TL-1 enzyme.

Among the capuramycin analogues tested against the MAC strains, SQ641 was the most active compound, followed by RKS2244, SQ922 and SQ997. The MIC of SQ641 ranged from ≤0.062 to 4.0 mg/L (Table 1), with an MIC90 of 2 mg/L. The order of activity of the positive control drugs against the same MAC strains was rifabutin > clarithromycin > amikacin > ethambutol. These are the four drugs that are generally used to treat MAC infections. The MIC of rifabutin, the most active compound against MAC, ranged from 0.0078 to 1.0 mg/L and the MIC90 was 0.25 mg/L.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)

| MIC (mg/L) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Colony type | SQ997 | SQ922 | SQ641 | RKS2244 | CLR | AMK | EMB | RFB |

| JSH1 | ST | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 0.125 |

| A5 | SO | 16 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 4 | 1 | 0.015 |

| 100 | SO | 16 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 | 4 | 0.031 |

| 101 | SO | 8 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 1 | 0.015 |

| 104 | IM | 16 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 0.015 |

| 109 | IM | 8 | 0.5 | ≤0.062 | 0.25 | 0.062 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.0078 |

| NIH-Cl1 | ST | 8 | >32 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0.062 |

| NIH-Cl2 | IM | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 32 | 2 | 0.0078 |

| NIH-Cl3 | RO | 16 | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 32 | 0.031 |

| NIH-Cl4 | IM | 8 | 2 | 0.125 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.0078 |

| MA4256 | RO | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | ND | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0.25 |

| MA4103 | SO | 8 | 4 | 2 | ND | 8 | 16 | 32 | 0.25 |

| MA4100 | ST | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | ND | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 0.125 |

| MA4252 | RO | 8 | 2 | 1 | ND | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0.25 |

| MA4124 | rough pinpoint | 8 | 8 | 2 | ND | >32 | 16 | 32 | 0.25 |

| MA2924 | ST | 4 | 2 | 1 | ND | 8 | 16 | 32 | 1 |

| MA4250 | ST | 8 | 4 | 2 | ND | 8 | 32 | >32 | 0.25 |

| MA4109 | ST | 8 | 2 | 2 | ND | 1 | 8 | 2 | 0.125 |

| MA4112 | smooth pinpoint | 8 | 4 | 1 | ND | 0.5 | 8 | >32 | 0.125 |

| MA4143 | ST | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | ND | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 |

CLR, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin; EMB, ethambutol; RFB, rifabutin; ST, smooth transparent; SO, smooth opaque; IM, intermediate; RO, rough opaque; ND, not done.

MIC determined in 7H9 broth with 0.05% Tween 80.

Coded compounds (including ethambutol) were sent to the University of Wisconsin for testing against MAP strains. When the code was revealed, among the six different capuramycin analogues tested, SQ641 was the most potent, with an MIC of 0.125–2 mg/L. SQ641 was followed by RKS2244 with an MIC of 2–16 mg/L. The MIC of the positive control, ethambutol, was 2–8 mg/L (Table 2). The capuramycin analogue susceptibility pattern of MAC and MAP strains was similar.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP)

| MIC/MBC (mg/L) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ997 |

SQ641 |

RKS2137 |

RKS2243 |

RKS2244 |

RS120029 |

EMB |

||||||||

| Strain | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC |

| Linda | 16 | 32 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 8 | >32 | ND | 4 | 8 |

| Ben | 32 | 64 | 1 | 4 | >4 | ND | >4 | ND | 8 | 32 | >4 | ND | 8 | 16 |

| Holland | 32 | ND | 2 | 8 | 16 | ND | >4 | ND | 16 | 64 | >32 | ND | 8 | 16 |

| Dominic | 16 | 32 | 2 | 16 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 32 | ND | ND | 4 | 16 |

| UCF3 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ND | 4 | ND | 4 | 4 | >4 | ND | 4 | 4 |

| UCF4 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 16 | ND | ND | 4 | 4 |

| UCF5 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 32 | ND | ND | 4 | 16 |

| UCF7 | 16 | 64 | 1 | 32 | >4 | ND | >4 | ND | 8 | 32 | >4 | ND | 8 | 64 |

| UCF8 | 8 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 4 | ND | 4 | ND | 2 | 2 | >4 | ND | 2 | 2 |

EMB, ethambutol; ND, not done.

SQ641 was the most active compound against both MKN strains, with MICs of 1 mg/L. RKS2244 was active against only one of the two strains tested. All of the five positive control drugs (rifampicin, clarithromycin, amikacin, moxifloxacin and ethambutol) were quite active against both strains (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antibacterial activities of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium kansasii (MKN) strains

| MIC (mg/L) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | SQ997 | SQ922 | SQ641 | RKS2244 | RIF | CLR | AMK | MXF | EMB |

| 35775 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.031 | 1 |

| 12478 | 16 | 16 | 1 | >32 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.125 | 2 |

RIF, rifampicin; CLR, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin; MXF, moxifloxacin; EMB, ethambutol.

MIC determined in 7H9 broth with 0.05% Tween 80 and 10% OADC.

Against MAB strains, SQ641 had the lowest MIC of all the compounds tested, including six positive control drugs. The MIC of SQ641 ranged from 0.25 to 1.0 mg/L. SQ997 and SQ922 were least active against MAB compared with activity against MAC and Mtb.16 Among the six positive controls, rifabutin showed the lowest MIC of 1–2 mg/L, which is higher than its MIC for MAC. The activity of the other five controls was variable, with cefoxitin showing the least activity. There was no correlation between colony morphology and the drug susceptibility of the MAB strains (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibacterial activities of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium abscessus (MAB) strains

| MIC (mg/L) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Colony morphology | SQ997 | SQ922 | SQ641 | CLR | AMK | RFB | FOX | MXF | CIP |

| 700869 | rough | 16 | 16 | 0.5 | >32 | 4 | 2 | 16 | >32 | >32 |

| MC5746 | rough | 16 | 16 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | >32 | 4 | 2 |

| MC5691 | smooth | 32 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 4 |

| MC5750 | rough | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 2 | 2 |

| MC5692 | smooth | 32 | 16 | 0.5 | >32 | >32 | 1 | 32 | 16 | 32 |

| MC5686 | rough | 32 | 16 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MC5706 | smooth | 16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 4 |

| MC5700 | rough | 32 | 16 | 1 | 0.5 | 8 | 2 | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| MC5676 | mucoid | 16 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 |

| MC5025 | rough | 32 | 16 | 0.25 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 4 |

| MC5712 | smooth | 32 | 16 | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

CLR, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin; RFB, rifabutin; FOX, cefoxitin; MXF, moxifloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

MIC determined in 7H9 broth with 0.05% Tween 80.

The MIC of SQ641 for MUL was 8 mg/L by agar dilution and 1 mg/L by microdilution. The MIC of clarithromycin was 1 and 0.125 mg/L and that of amikacin was 0.5 and 1 mg/L by agar dilution and microdilution, respectively. Variation in the MIC between agar dilution and broth dilution methods is not uncommon, and depends on the medium, the drug and the organism.21

To ascertain whether iron affects the in vitro activity of SQ641, we determined the MICs of SQ641 for MSMG, MAB (700869) and MAC (101, JSH1 and NIH-Cl1) in Sautons' medium with and without iron. There was no difference in the MIC of SQ641 in the absence of iron, indicating that iron has no role in the in vitro activity of the compound.

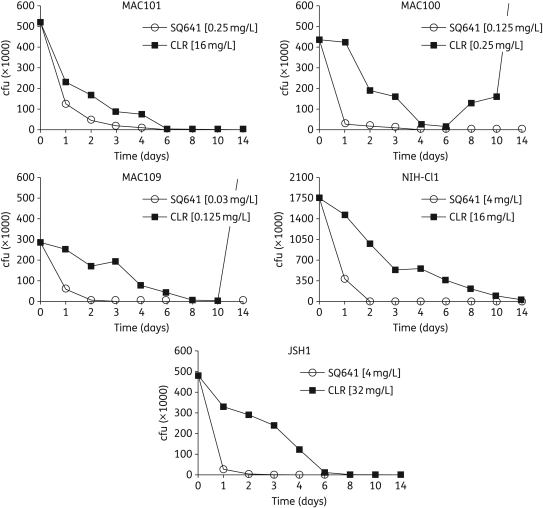

Rate of killing of MAC

The rate at which SQ641 and clarithromycin killed was determined against five different MAC strains. Two of these strains (NIH-Cl1 and JSH1) formed smooth transparent colonies and are relatively more resistant to antimicrobial agents. All the five MAC strains were killed by SQ641 much faster than by clarithromycin. SQ641 reduced viability by ≥50% within 24 h in all five strains, and by ≥90% within 2 days in three strains and within 4 days in two strains. Clarithromycin took nearly 2 days to reduce viability by ≥50% and ≥6 days to reduce viability by ≥90%. In one strain, clarithromycin took 2 weeks to kill 90%, and in another two strains the organisms grew back to more than the initial cfu (Figure 2). In all the strains exposed to clarithromycin, viable organisms could be detected at the end of 2 weeks, but not so with SQ641 exposure, showing that SQ641 kills MAC thoroughly and faster than clarithromycin.

Figure 2.

Time-to-kill graphs of SQ641 against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). SQ641 and clarithromycin (CLR) were tested at 1× MBC.

Bactericidal activity

Capuramycin analogues were not only bactericidal against Mtb (MBC/MIC ratio 1 to 2), but were also lytic, causing bacterial disintegration.16 SQ641 was also bactericidal against NTM, with an MBC/MIC ratio of 1 to 32 (Tables 2 and 5). In fact, SQ641 had a favourable MBC/MIC ratio (≤2) against the majority of the strains (17 out of 26) and the compound was more bactericidal against MAC than MAB. The MBC/MIC ratio of clarithromycin against MAC strains (n = 9) was very wide, ranging from 1 to 128; the ratio was 8 against two strains, 128 against one strain, 64 against one strain and 1 against the rest. The MBC/MIC ratio of amikacin against five MAB strains ranged from 1 to >4 and two strains had a ratio of ≥4. The MBC/MIC ratio of rifampicin against MKN and streptomycin against MSMG was between 1 and 2 (Table 5). Therefore, the bactericidal activity of SQ641 is comparable to or better than that of the existing drugs used for the treatment of NTM infections.

Table 5.

Bactericidal activity of SQ641 against different non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM)

| NTM | Strain | SQ641 |

CLR/RIF/AMK/STRa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) | MBC (mg/L) | MBC/MIC ratio | MIC (mg/L) | MBC (mg/L) | MBC/MIC ratio | ||

| MAC | A5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | 16 | 64 |

| JSH1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 8 | |

| 100 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| 101 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.125 | 16 | 128 | |

| 104 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 109 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| NIH-Cl1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 8 | |

| NIH-Cl2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| NIH-Cl4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| MKN | 12478 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 1 |

| 35775 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 2 | |

| MAB | 700869 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 32 | 2 |

| MC5750 | 0.25 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | |

| MC5691 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | >32 | >4 | |

| MC5686 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 1 | |

| MC5746 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 4 | |

| MSMG | MC2155 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

CLR, clarithromycin; RIF, rifampicin; AMK, amikacin; STR, streptomycin; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; MKN, Mycobacterium kansasii; MAB, Mycobacterium abscessus; MSMG, Mycobacterium smegmatis.

MIC and MBC determined in 7H9 broth with 0.05% Tween 80.

aCLR against MAC, RIF against MKN, AMK against MAB and STR against MSMG.

Synergistic activity with other antimycobacterial drugs

Most mycobacterial infections are treated with a combination of multiple drugs in a regimen. Synergistic interaction with existing drugs is a valuable attribute of a new drug candidate. Among the four capuramycin analogues, only SQ641 showed synergy with other antimycobacterial drugs against NTM: it was synergistic (FICI ≤ 0.5) with ethambutol across all the ethambutol-susceptible NTM, even in ethambutol-resistant MAC JSH1 strain (Table 6). Synergy between SQ641 and ethambutol was also observed against Mtb.16 SQ641 was also synergistic with streptomycin and rifabutin in MAB.

Table 6.

Synergy between SQ641 and other antimicrobial agents against NTM

| MIC (mg/L) |

FICIa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Drug combination | alone | combination | |

| MAC (A5) | SQ641 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.75 |

| CLR | 0.125 | 0.031 | ||

| SQ641 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.75 | |

| AMK | 2.0 | 0.5 | ||

| SQ641 | 0.25 | 0.062 | 0.31 | |

| EMB | 1.0 | 0.062 | ||

| MAC (JSH1) | SQ641 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| CLR | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.625 | |

| AMK | 16.0 | 8.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| EMB | 32.0 | 8.0 | ||

| MAC (NIH-Cl1) | SQ641 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| CLR | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.75 | |

| AMK | 8.0 | 4.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 2.0 | 0.062 | 0.281 | |

| EMB | 8.0 | 2.0 | ||

| MAB (ATCC 700869) | SQ641 | 0.5 | 0.062 | 0.375 |

| STR | 8.0 | 2.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 0.5 | 0.062 | 0.25 | |

| RFB | 2.0 | 0.25 | ||

| MSMG (MC2155) | SQ641 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| INH | 8.0 | 1.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.75 | |

| RIF | 8.0 | 2.0 | ||

| SQ641 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| STR | 0.5 | 0.25 | ||

| SQ641 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 0.375 | |

| EMB | 0.5 | 0.12 | ||

CLR, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin; EMB, ethambutol; STR, streptomycin; RFB, rifabutin; RIF, rifampicin; FICI, fractional inhibitory concentration index; INH, isoniazid.

MIC determined in 7H9 broth with 0.05% Tween 80.

a≤0.5, synergistic (bold font); >4.0, antagonistic; >0.5–4, no interaction.19

Discussion

SQ641 was highly effective across all mycobacterial species, with the best activity against MAC. Generally, susceptibility of MAC strains to antimicrobial agents is highly variable. With SQ641, variability was much less and it was faster acting than the other anti-MAC drugs. SQ641 is derived from SQ997 by acylation with a decanoic anhydride, which makes it more lipophilic than the other capuramycin analogues and improves its permeability through the lipid-rich mycobacterial cell wall. Even though the SQ641 IC50 against TL-1 is considerably higher than that of its parent compound (see Figure 1), its MIC is significantly lower. Dissonance between TL-1 IC50 values and MIC was apparent with many other compounds in this series.7 Since TL-1 is a transmembrane protein, with its active site facing the cytoplasmic side, antibiotics have to permeate through bacterial envelope layers and the plasma membrane before reaching this target. Compounds vary in their permeability and active efflux. In any case, MIC rather than IC50 is the most effective indicator of the efficacy of a compound.

To improve efficacy and prevent the development of drug resistance, mycobacterial infections are always treated with a combination of antimicrobial agents. Drug combinations that are synergistic are generally more effective and, therefore, preferable.22–25 In this context, SQ641 is synergistic with ethambutol against MAC (including an ethambutol-resistant strain), MSMG and Mtb.16 The drug is also synergistic with rifabutin and streptomycin against MAB. By blocking PG biosynthesis, SQ641 may improve the permeability and accumulation of the companion drugs. In vitro synergy between antibiotics, however, should be interpreted with caution, since in vivo plasma and tissue concentrations of the individual antibiotics in combination depends on their pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics as well as drug–drug interactions. Whether the observed in vitro synergy between SQ641 and other antimycobacterial drugs prevail in vivo is being investigated. Among the NTM, infections due to MAC and MAB are recalcitrant to treatment, and there is a real dearth of new antimicrobial agents to treat such infections. Excellent in vitro activity combined with synergistic effects with other antimycobacterial drugs underscores the potential utility of SQ641 for the treatment of NTM infections.

SQ641 has several very attractive features: it has a unique mode of action compared with all commercially available antibiotics;4,6–8 it is bactericidal and fast-acting; and it displays lasting post-antibiotic effect.16 Furthermore, it induces a low frequency of resistance development, is effective at acidic pH, is active against slowly replicating bacteria (V. M. Reddy, Sequella, Inc.), is synergistic with other antimycobacterial drugs and is very stable. SQ641 is, however, poorly absorbed when delivered orally. Intranasally, SQ641 suspension showed modest in vivo activity against MAC and Mtb.9 SQ641 solubilized in tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) or TPGS-micellar formulations and given parenterally also showed modest efficacy against Mtb in a chronic TB mouse model.26 In this set of experiments,26 drug dosage was limited due to toxicity of the delivery vehicle. To harness SQ641's attractive features and overcome its limitations, we are chemically modifying the compound and developing particulate drug formulations to target the drug to macrophages, subvert efflux pumps, and enhance intracellular and in vivo efficacy.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH (1R43AI084211-01).

Transparency declarations

T. D., E. B., L. E., C. A. N. and V. M. R. are Sequella, Inc. employees. L. E. and C. A. N. own stock and T. D., E. B. and V. M. R. own stock options in Sequella, Inc. M. Y. K. and M. T. C.: none to declare.

References

- 1.Bugg TD, Lloyd AJ, Roper DI. Phospho-MurNAc-pentapeptide translocase (MraY) as a target for antibacterial agents and antibacterial proteins. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2006;6:85–106. doi: 10.2174/187152606784112128. doi:10.2174/187152606784112128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura K, Bugg TD. Recent advances in antimicrobial nucleoside antibiotics targeting cell wall biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:252–73. doi: 10.1039/b202149h. doi:10.1039/b202149h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien R. The treatment of tuberculosis. In: Reichman LB, Hershfield ES, editors. Tuberculosis: A Comprehensive International Approach. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 207–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi H, Sato S, Yoshida S, et al. Capuramycin, a new nucleoside antibiotic. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot. 1986;39:1047–53. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muramatsu Y, Muramatsu A, Ohnuki T, et al. Studies on novel bacterial translocase I inhibitors, A-5300359s. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and structure elucidation of A-500359 A, C, D and G. J Antibiot. 2003;56:243–52. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotoda H, Furukawa M, Daigo M, et al. Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of capuramycin analogues. Part 1: substitution of the azepan-2-one moiety of capuramycin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2829–32. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00596-1. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotoda H, Daigo M, Furukawa M, et al. Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of capuramycin analogues. Part 2: acylated derivatives of capuramycin-related compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2833–36. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00597-3. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotoda H, Kanenko M, Inukai M, et al. Antibacterial Compound. USA: Sankyo Company, Limited (Tokyo, JP); 2007. US Patent #7157442B2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koga T, Fukuoka T, Doi N, et al. Activity of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare in vitro and in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:755–60. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh417. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chacon O, Bermudez LE, Barletta RG. Johne's disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:329–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123726. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce ES. Where are all the Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in patients with Crohn's disease? PLoS Path. 2009;5:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uzoigwe JC, Khaitsa ML, Gibbs PS. Epidemiological evidence for Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis as a cause of Crohn's disease. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:1057–68. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807008448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756–63. doi: 10.1086/504381. doi:10.1086/504381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson PDR, Stinear T, Small PLC, et al. Buruli ulcer (M. ulcerans): new insights and new hope for disease control. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2:282–86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020108. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy VM, Einck L, Nacy CA. In vitro antimycobacterial activities of capuramycin analogues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:719–21. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01469-07. doi:10.1128/AAC.01469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace RJ, Nash DR, Steel LC. Susceptibility testing of slowly growing mycobacteria by a microdilution MIC method with 7H9 broth. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:976–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.976-981.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnan MY, Manning EJB, Collins MT. Comparison of three methods for susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis to 11 antimicrobial drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:310–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp184. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odds FC. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy VM, Luna-Herrera J, Gangadharam PRJ. Pathobiological significance of colony morphology in Mycobacterium avium complex. Microbial Pathog. 1996;21:97–109. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0046. doi:10.1006/mpat.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heifets LB. Antituberculosis drugs: antimicrobial activity in vitro. In: Heifets LB, editor. Drug Susceptibility in the Chemotherapy of Mycobacterial Infections. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 13–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chadwick EG, Shulman ST, Yogev R. Correlation of antibiotic synergy in vitro and in vivo: use of an animal model of neutropenic gram-negative sepsis. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:670–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moody JA, Fasching CE, Petterson LR, et al. Ceftazidime and amikacin alone and in combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1987;6:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(87)90115-5. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(87)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le T, Bayer AS. Combination antibiotic therapy for infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:615–21. doi: 10.1086/367661. doi:10.1086/367661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacqueline C, Navas D, Batard E, et al. In vitro and in vivo synergistic activities of linezolid combined with subinhibitory concentrations of imipenem against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:45–51. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.45-51.2005. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.1.45-51.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikonenko BV, Reddy VM, Protopopova M, et al. Activity of SQ641, a capuramycin analog, in a murine model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;53:3138–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00366-09. doi:10.1128/AAC.00366-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]