Abstract

Objectives

This article describes successful institutionally-based programs for providing high quality palliative care to people with cancer and their family members. Challenges and opportunities for program development are also described.

Data Sources

Published literature from 2000 to present describing concurrent oncology palliative care clinical trials, standards and guidelines were reviewed.

Conclusion

Clinical trials have demonstrated feasibility and positive outcomes and formed the basis for consensus guidelines that support concurrent oncology palliative care models.

Implications for nursing practice

Oncology nurses should advocate for all patients with advanced cancer and their families to have access to concurrent oncology palliative oncology care from the time of diagnosis with a life-limiting cancer.

Keywords: Cancer palliative care models, review, palliative care standards

In 2009, cancer claimed more than 565,000 American lives, at a rate of approximately 1,500 people a day.1 As most cancers are not immediately fatal, patients will experience months to years of life-limiting illness with a relatively brief period of decline prior to death.2–5Since the early 1980s hospice services have been available to provide holistic pain and symptom management resources to patients with cancer who approach end of life (EOL) and their families. Although hospice services have been a tremendous source of care and comfort they are often “too little too late” because hospice referrals frequently occur close to the time of death.6, 7 Two Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports detailed unnecessary suffering resulting from inadequacies of the current health care system in providing end of life (EOL) care.8, 9

The goal of palliative care is “ to prevent and relieve suffering and to support the best possible quality of life for patients’ and their families, regardless of the stage of the disease or the need for other therapies.”10 (p.6) Although the idea of offering palliative care services early in the illness trajectory is not new, it was considered radical when originally proposed by the World Health Organization11. Until recently palliative care was rarely available for patients and their families early in the disease trajectory. So while it is imperative to improve cancer care systems at EOL, preventing the use of unwanted, aggressive interventions may have a greater overall impact on the quality of EOL care.3, 12, 17 International oncology and palliative care expert panels9–11, 18 have recommended early introduction of concurrent oncology palliative care (COPC) to improve patients’ quality of life and EOL care. ‘Simultaneous’ and ‘comprehensive supportive care’ are synonymous model names.19–21 The central thrust of COPC is to ensure that patient values, preferences, and treatment goals guide care throughout the illness, from diagnosis through death.

Despite demonstrated feasibility and increasing acceptance, cancer centers wishing to implement concurrent oncology palliative care still face many challenges. The purpose of this article is to first describe the structure, processes, and outcomes of COPC using one successful model of patient and family-centered oncology palliative care, and then to summarize innovative ways to overcome three key challenges of implementation: 1) ‘gate-keeping’, 2) providing quality care during care transitions, and 3) measuring outcomes of success. Readers are also referred to other excellent sources that describe program exemplars and provide guidance for program development10, 22–24.

Successful Models of Providing Oncology Palliative Care: Structure, Processes, Outcomes

In 1998 the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) program entitled “Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care” issued a call for demonstration projects and four cancer centers were funded to bring hospice principles earlier into the disease trajectory. 25–28 These four centers pilot-tested different models of integrated care and were able to demonstrate feasibility and acceptance by both patients and clinicians.19, 20, 28, 29 Founded on these early successes, numerous cancer organizations have developed standards and guidelines that recommend COPC from the time of diagnosis of a life-limiting cancer.9, 30, 31

According to the National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care and the National Quality Forum (NQF) Preferred Practices guidelines10, 18 model palliative care programs should address the eight domains of palliative care (see Tables 1 and 2). However, it is generally not known to what extent palliative programs are consistent with these guidelines. A recent survey of 71 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers and 71 non-NCI cancer centers was conducted to determine the availability of palliative care services in cancer centers. In that study the authors did not use the NCP guidelines, but rather defined palliative care services as “the presence of at least 1 palliative care physician”.32 (p. 1056) Using this definition virtually all NCI-designated cancer centers and 50 (78%) of the non-NCI cancer centers surveyed indicated that they had a ‘currently active’ palliative care program.

Table 1.

National Consensus Panel Eight Domains of Quality Palliative Care and Corresponding National Quality Forum Preferred Practices ([BOLDED] ENTRIES REFER TO CORRESPONDING DOMAIN FROM – see Table 2)

| NCP Domains of Quality Palliative Care |

NQF Preferred Practices |

|---|---|

| 1. Structure and processes of care | 1. Provide palliative and hospice care by an interdisciplinary team of skilled palliative care professionals, including, for example, physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, spiritual care counselors, and others who collaborate with primary healthcare professional(s). [4. STAFFING] |

| 2. Provide access to palliative and hospice care that is responsive to the patient and family 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. [3. AVAILABILITY] | |

| 3. Provide continuing education to all healthcare professionals on the domains of palliative care and hospice care. [8. EDUCATION] | |

| 4. Provide adequate training and clinical support to assure that professional staff are confident in their ability to provide palliative care for patients. [12. STAFF WELLNESS] | |

| 5. Hospice care and specialized palliative care professionals should be appropriately trained, credentialed, and/or certified in their area of expertise. [4. STAFFING] | |

| 6. Formulate, utilize, and regularly review a timely care plan based on a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment of the values, preferences, goals, and needs of the patient and family and, to the extent that existing privacy laws permit, ensure that the plan is broadly disseminated, both internally and externally, to all professionals involved in the patient’s care. | |

| 7. Ensure that upon transfer between healthcare settings, there is timely and thorough communication of the patient’s goals, preferences, values, and clinical information so that continuity of care and seamless follow-up are assured.[11. CONTINUITY OF CARE] | |

| 8. Healthcare professionals should present hospice as an option to all patients and families when death within a year would not be surprising and should reintroduce the hospice option as the patient declines. [11. CONTINUITY OF CARE] | |

| 9. Patients and caregivers should be asked by palliative and hospice care programs to assess physicians’/healthcare professionals’ ability to discuss hospice as an option. | |

| 10. Enable patients to make informed decisions about their care by educating them on the process of their disease, prognosis, and the benefits and burdens of potential interventions. | |

| 11. Provide education and support to families and unlicensed caregivers based on the patient’s individualized care plan to assure safe and appropriate care for the patient. | |

| 2. Physical aspects of care | 12. Measure and document pain, dyspnea, constipation, and other symptoms using available standardized scales. [5. MEASUREMENT & 6. QI ] |

| 13. Assess and manage symptoms and side effects in a timely, safe, and effective manner to a level that is acceptable to the patient and family. [5. MEASUREMENT & 6. QI ] | |

| 3. Psychological and psychiatric aspects of care | 14. Measure and document anxiety, depression, delirium, behavioral disturbances, and other common psychological symptoms using available standardized scales. [5. MEASUREMENT & 6. QI ] |

| 15. Manage anxiety, depression, delirium, behavioral disturbances, and other common psychological symptoms in a timely, safe, and effective manner to a level that is acceptable to the patient and family. [5. MEASUREMENT & 6. QI ] | |

| 16. Assess and manage the psychological reactions of patients and families (including stress, anticipatory grief, and coping) in a regular, ongoing fashion in order to address emotional and functional impairment and loss. [5. MEASUREMENT & 6. QI ] | |

| 17. Develop and offer a grief and bereavement care plan to provide services to patients and families prior to and for at least 13 months after the death of the patient. [9. BEREAVEMENT] | |

| 4. Social aspects of care | 18. Conduct regular patient and family care conferences with physicians and other appropriate members of the interdisciplinary team to provide information, to discuss goals of care, disease prognosis, and advance care planning, and to offer support. |

| 19. Develop and implement a comprehensive social care plan that addresses the social, practical, and legal needs of the patient and caregivers, including but not limited to relationships, communication, existing social and cultural networks, decision-making, work and school settings, finances, sexuality/intimacy, caregiver availability/stress, and access to medicines and equipment. [4. STAFFING] | |

| 5. Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care |

20. Develop and document a plan based on an assessment of religious, spiritual, and existential concerns using a structured instrument, and integrate the information obtained from the assessment into the palliative care plan. [4. STAFFING] |

| 21. Provide information about the availability of spiritual care services, and make spiritual care available either through organizational spiritual care counseling or through the patient’s own clergy relationships. [4. STAFFING] | |

| 22. Specialized palliative and hospice care teams should include spiritual care professionals appropriately trained and certified in palliative care. [4. STAFFING] | |

| 23. Specialized palliative and hospice spiritual care professionals should build partnerships with community clergy and provide education and counseling related to end-of-life care. [4. STAFFING] | |

| 6. Cultural aspects of care | 24. Incorporate cultural assessment as a component of comprehensive palliative and hospice care assessment, including but not limited to locus of decision-making, preferences regarding disclosure of information, truth telling and decision-making, dietary preferences, language, family communication, desire for support measures such as palliative therapies and complementary and alternative medicine, perspectives on death, suffering, and grieving, and funeral/burial rituals. |

| 7. Care of the imminently dying patient |

26. Recognize and document the transition to the active dying phase, and communicate to the patient, family, and staff the expectation of imminent death. |

| 27. Educate the family on a timely basis regarding the signs and symptoms of imminent death in an age- appropriate, developmentally appropriate, and culturally appropriate manner. | |

| 28. As part of the ongoing care planning process, routinely ascertain and document patient and family wishes about the care setting for the site of death, and fulfill patient and family preferences when possible. [11. CONTINUITY OF CARE] | |

| 29. Provide adequate dosage of analgesics and sedatives as appropriate to achieve patient comfort during the active dying phase, and address concerns and fears about using narcotics and of analgesics hastening death. | |

| 30. Treat the body after death with respect according to the cultural and religious practices of the family and in accordance with local law. [9. BEREAVEMENT | |

| 31. Facilitate effective grieving by implementing in a timely manner a bereavement care plan after the patient’s death, when the family remains the focus of care. [9. BEREAVEMENT | |

| 8. Ethical and legal aspects of care | 32. Document the designated surrogate/decisionmaker in accordance with state law for every patient in primary, acute, and long-term care and in palliative and hospice care. |

| 33. Document the patient/surrogate preferences for goals of care, treatment options, and setting of care at first assessment and at frequent intervals as conditions change. | |

| 34. Convert the patient treatment goals into medical orders, and ensure that the information is transferable and applicable across care settings, including long- term care, emergency medical services, and hospital care, through a program such as the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) program. | |

| 35. Make advance directives and surrogacy designations available across care settings, while protecting patient privacy and adherence to HIPAA regulations, for example, by using Internet-based registries or electronic personal health records. | |

| 36. Develop healthcare and community collaborations to promote advance care planning and the completion of advance directives for all individuals, for example, the Respecting Choices and Community Conversations on Compassionate Care programs. | |

| 37. Establish or have access to ethics committees or ethics consultation across care settings to address ethical conflicts at the end of life. | |

| 38. For minors with decision-making capacity, document the child’s views and preferences for medical care, including assent for treatment, and give them appropriate weight in decision-making. Make appropriate professional staff members available to both the child and the adult decision-maker for consultation and intervention when the child’s wishes differ from those of the adult decision-maker. | |

Data from: 10, 18, 24

TABLE 2.

Consensus Recommendations for Operational Features of Palliative Care Programs

| RECOMMENDATIONS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | NQFa | Must have | Should have |

|

1. Program Administration To effectively integrate palliative care services into hospital culture and practice, so that the program’s mission is aligned with that of the hospital, the program must have both visibility and voice within the hospital management structure. This can best be accomplished by (1) ensuring that a program has a designated program director, with dedicated funding for program director duties and (2) a routine mechanism for program reporting and planning that is integrated into the hospital management committee structure. |

Palliative care program staff integrated into the management structure of the hospital to ensure that program consideration of hospital mission/goals. Processes, outcomes, and strategic planning are developed in consideration of hospital mission/goals. |

Systems that integrate palliative care practices into the care of all seriously ill patients, not just those seen by the program. |

|

|

2. Types of Services The three components of a fully integrated palliative care program are an inpatient consultation service, outpatient practice, and geographic inpatient unit. All three serve different but complementary functions to support patients/ families through the illness experience. Because a consultation practice has the ability to serve patients throughout the entire hospital, this is typically recommended as the first point of program development. |

A consultation service that is available to all hospital inpatients. |

Resources for outpatient palliative care services, especially in hospitals with more than 300 beds. An inpatient palliative care geographic unit, especially in hospitals with more than 300 beds. |

|

|

3. Availability Patients, families and hospital staff need palliative care services that are available for both routine and emergency services. |

2 | Monday–Friday inpatient consultation availability and 24/7 telephone support. |

24/7 inpatient consultation availability, especially in hospitals with more than 300 beds. |

|

4. Staffing The following disciplines are essential to provide palliative care services: physician, nursing, social work and chaplaincy. In addition, mental health services must be available. Depending on the institution and staff, basic mental health screening services can be provided by an appropriately trained social worker, chaplain, or nurse with psychiatric training. Ideally a psychologist or psychiatrist are also available for complex mental health needs. Social work, chaplaincy, and mental health services can be provided by dedicated palliative care fulltime equivalent positions or by existing hospital staff, although their work in support of the palliative care program will still need to be accounted and paid for, and not just “added on” to their existing job responsibilities. |

1, 5, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 |

Specific funding for a designated palliative care physician(s). All certified in hospice and palliative medicine (HPM) or committed to working toward board certification. Specific funding for a designated palliative care nurse(s), with advance practice nursing preferred. All program nurses must be certified by the National Board for Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nursing (NBCHPN) or committed to working toward board certification. Appropriately trained staff to provide mental health services. Social worker(s) and chaplain(s) available to provide clinical care as part of an interdisciplinary team. Administrative support (secretary/ administrative assistant position) in hospitals with either more than 150 beds or a consult service with volume >15 consults per month. |

|

|

5. Measurement Providing evidence of the value of palliative care programs to patients, families, referring physicians and hospital administrators is critical for program sustainability and growth. Key outcome measures can be divided into four domains (examples provided):

|

12, 13, 14, 15, 16 |

Operational metrics for all consultations. Customer, clinical and financial metrics that are tracked either continuously or intermittently. |

|

|

6. Quality Improvement Palliative care programs must be held accountable to the same quality-improvement standards as other hospital clinical programs. |

12, 13, 14, 15, 16 |

Quality improvement activities, continuous or intermittent, for (a) pain, (b) non-pain symptoms, (c) psychosocial/spiritual distress and (d) communication between health care providers and patients/ surrogates. |

|

|

7. Marketing As a new specialty, the palliative care program is responsible for making its presence and range of services known to the key stakeholders for quality care. |

Marketing materials and strategies appropriate for hospital staff, patients, and families. |

||

|

8. Education As a new specialty, the palliative care program is responsible for helping develop and coordinate educational opportunities and resources to improve the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behavior of all health professionals |

3 | Palliative care educational resources for hospital physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, health professional trainees, and any other staff the program feels are essential to fulfill its mission and goals. |

|

|

9. Bereavement Services There are no currently accepted best practice features of bereavement services to recommend. Common elements present in many programs include telephone or letter follow-up, sympathy cards, registry of community resources for support groups and counseling services, an remembrance services. All programs are encouraged to develop a bereavement policy and make changes as needed through quality-improvement initiatives. |

17, 30, 31 | A bereavement policy and procedure that describes bereavement services provided to families of patients impacted by the palliative care program. |

|

|

10. Patient Identification In most hospitals, palliative care consultations originate from a physician order. To facilitate referrals for “at-risk” patients, many hospitals have begun adopting screening |

A working relationship with the appropriate departments to adopt palliative care screening criteria for patients in the emergency department, general med/surgical wards and intensive care units. |

||

|

11. Continuity of Care Coordination of care as patients move from one care site to another is especially critical for patients with serious,often life-limiting diseases, and is a cornerstone of palliative care clinical work. |

7, 8, 28 | Policies and procedures that specify the manner in which transitions across care sites (e.g., hospital to home hospice) will be handled to ensure excellent communication between facilities. A working relationship with one or more community hospice providers. |

|

|

12. Staff Wellness The psychological demands on palliative care staff are often overwhelming, placing practitioners at risk for burnout and a range of other mental health problems. Common examples of team wellness activities are team retreats, regularly scheduled patient debriefing exercises, relaxation-exercise training and individual referral for staff counseling. |

4 | Policies and procedures that promote palliative care team wellness. |

NQF column numbers represent the specific National Quality Forum Hospice and Palliative Medicine Preferred Practice. (SEE TABLE 1) Data from10, 18, 24

The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) is a national organization that assists hospitals and health systems nationwide to establish high quality palliative care programs (see www.CAPC.org). They describe staff models (see Table 3) that developing palliative care programs should consider with inpatient, outpatient, and community (home care) components. In Hui et al.’s survey (33), NCI-designated centers were more likely than non-NCI centers to have an inpatient consultation team (92% vs 56%; <.001) or outpatient clinic (59% vs 22%; <.001). However, few NCI and non-NCI-designated programs had dedicated acute care beds,(26% vs 20%, or institution operated hospice programs,31% vs. 42%, respectively.32

Table 3.

Palliative Care Program Model Options

| Characteristics | Solo Practitioner Model |

Full Team Model | Geographic Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophy/Approach |

|

|

|

| Service Model |

|

|

|

| Staffing and Budget Implications |

|

|

|

| Patient Volume Thresholds |

|

|

|

| Benefits/Advantages |

|

|

|

| Disadvantages/Threats |

|

|

|

At the Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC), an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center serving a mostly rural population in northern New England, a successful COPC program for patients newly-diagnosed with advanced cancer was introduced in 1999 as the RWJF-funded Project ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends) demonstration project. Over the past decade, this program has grown to a full service clinical and research program consistent with the eight domains of the NCP guidelines. From 1999–2001, Project ENABLE served 380 patients (and their caregivers) (deaths=268)12, 28. The aims of the project were to determine whether: 1) a palliative care intervention could be implemented in three distinctly different cancer care systems (an NCI-designated cancer center, a community ambulatory private practice, and a rural cancer outreach clinic), and 2) the intervention could be initiated at the time of diagnosis of advanced stage cancer. Patients with advanced lung, gastrointestinal, and breast cancer were eligible to participate. The ENABLE intervention consisted of an advanced practice palliative care nurse (APPCN) and a series of in-person, group psycho-educational seminars called Charting Your Course (CYC). The APPCN met with each patient to conduct a broad palliative care evaluation that covered physical, psychosocial, spiritual and functional needs of the patient. She was then responsible for coordinating care within the cancer center and in the patient’s community in order to meet these needs. Patients were followed by the APPCN during cancer center visits and by phone until death. CYC was a four-session seminar series for patients and family members that covered a broad array of topics including learning problem-solving skills, managing symptoms, financial information, complementary therapies / nutrition, family issues, community resources, spiritual issues, decision making and advance care planning, overcoming barriers to communication with clinicians and family, and dealing with unfinished business, loss, and grief. The materials for the seminars were also available in a self-help, manualized format for patients who could not attend the seminars in person.

Despite positive results, a number of problems emerged. First, the authors discovered that one APPCN could not evaluate and follow all eligible patients on a face-to-face basis. The number of patients who were interested in participating in the program and the hectic nature of the oncology clinics made one-to-one interactions for all patients impossible. Although many enrolled patients were interested in attending the CYC seminars, approximately 50% could not attend because of distance, lack of transportation or other limiting physical factors. Consequently, the essential content of the CYC intervention was provided by the APPCN over the phone and by sending materials via mail, both of which turned out to be effective strategies. Based on this experience and the success of other phone-based interventions being tested in the institution’s community practices,33, 34 the authors provided the intervention by phone in a subsequent randomized clinical trial (RCT)35.

Second, the intervention was not designed to have the robust clinical interaction offered by an interdisciplinary team. So with generous support from a philanthropic donor, an internationally recognized leader in palliative medicine was recruited to construct an interdisciplinary palliative care clinical team. And finally, the original demonstration project was designed only as a feasibility project. To determine effectiveness relative to patient and family outcomes, the program was subsequently tested in the ENABLE II RCT (R01 CA101704) (N=322; deaths=231).35 Although the clinical palliative care program at NCCC now extends to non-cancer patient populations this article focuses on the program as it relates to cancer patients.

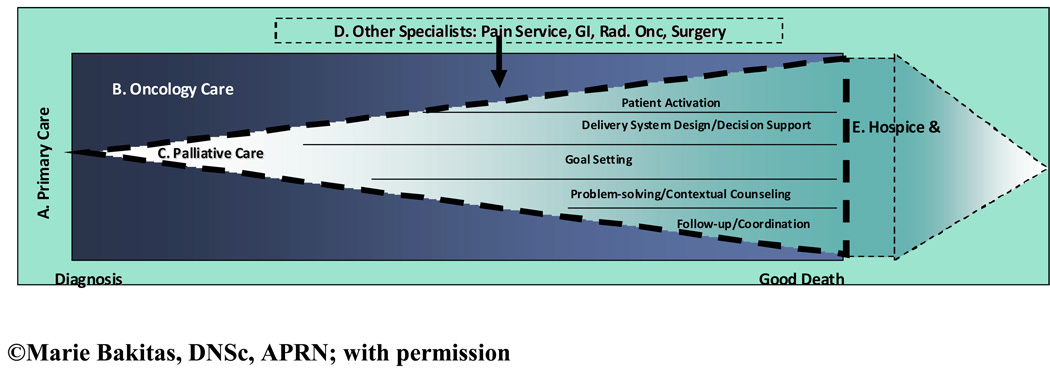

In the NCCC ENABLE COPC model, illustrated in Figure 1, patients are managed throughout the cancer trajectory within the context of primary care (A, the outermost area of the diagram). Although oncology care (i.e., anti-cancer treatments) predominates (B, the darker shaded section of the diagram), COPC is introduced at the time of an advanced cancer diagnosis (C, light-colored inner section of the diagram). The theoretical orientation of ENABLE was based on the principles of prevention,36, 37 the World Health Organization (WHO) Continuum of Care model,11 and the team’s prior research using the Chronic Care Model (CCM) to develop ‘informed, activated patients’.34, 38, 40 A CCM-based telephone intervention that focused on patient activation or empowerment, an essential element of a productive clinical interaction, was successful in improving rural primary care patients clinical care and outcomes.34 Consequently, the authors adapted and tested it in the palliative cancer population in the RCT called ENABLE II.25, 28, 35 The ENABLE II intervention targeted the CCM “5 As” of behavior change (ask, advise, agree, assist, and arrange).41, 42 In ENABLE II, specially-trained palliative care advance practice nurses implemented a manualized curriculum to educate patients in problem-solving and communication skills. The goal was to empower patients to: 1) share their personal values, life circumstances, and expectations for care with their clinicians; 2) achieve their desired level of participation in decision-making;43 and 3) identify needed information for symptom self-care to manage the predictable biopsychosocial challenges of advanced, life-limiting cancer. As seen within section C of Figure 1, the CCM “5 As” comprise the palliative care counseling domains: patient activation, decision support, goal setting, problem-solving, and coordination.41

Figure 1.

A Model of Concurrent Oncology Palliative Care

As the effectiveness of disease-modifying anti-cancer treatments lessen (section B), the use of palliative care strategies increases (section C). If complex palliative care issues arise, other specialists may be consulted (e.g., Pain Service for placement of an intraspinal pain pump) (section D in the diagram). Towards the end of life, hospice services (section E in the diagram) may be integrated to provide more intensive support in the home and community including bereavement support for family members following the patient’s death. Finally, as family members transition back to primary care, hospice support decreases. Dashed lines in the diagram signify ‘porous’ boundaries between different care systems.

The ENABLE II RCT outcomes showed that compared to a usual care control group, intervention participants had higher quality of life (QOL) and mood on the assessments following the intervention and prior to death. Post-hoc analyses revealed an unexpected finding--intervention participants had a lower risk of death in the year after enrollment (hazard ratio 0.67 [95% CI, 0.496–0.906] p = 0.009) and a median survival of 14 vs. 8.5 months (p = 0.14).35

Although the ENABLE COPC model preceded publication of the NCP guidelines,10 all eight NCP domains were addressed in the model. The program now consists of integrated, interdisciplinary clinical and research teams that provide care via outpatient and outreach clinics, phone-based prospective and follow-up care, and inpatient consultation, including oversight of EOL care on an inpatient oncology/hematology special care unit. As a tertiary center in a predominantly rural environment, the palliative care service collaborates closely with dozens of community-based hospice programs across Northern New England. Additionally, a focused effort, called the North Country Palliative Care Collaborative (NCPCC) (funded by the Tillotson Foundation)44 is comprised of 150 individuals, representing hospitals, home health and hospice agencies, nursing homes, physicians’ practices, community pharmacies, and other social service providers. The goal of the NCPCC is to raise community awareness and to provide palliative and EOL care expertise to address the specific challenges of providing palliative care in rural communities. The knowledge and specialized resources developed will contribute to national standards for best practices in serving rural populations.

The next stage of development for the program is to expand this care model to other oncology patients including those who are not based exclusively at the cancer center, but rather receive their oncology care primarily in their own communities. Although this intervention was originally tested in ‘poor prognosis’ solid tumor patients, a follow up RCT is now testing this approach in patients with hematological malignancies. Research indicates that palliative care is frequently not offered to this population.45, 46

Despite many successes, the program has faced a number of challenges. The three challenges that have been of greatest concern and are common among both developing and mature COPC programs are: 1) establishing structures and processes to identify all appropriate patients and overcome so called ‘gate-keeping’ whereby patients are not referred early for COPC; 2) maintaining consistent, expert palliative care across multiple transitions of care from diagnosis to EOL; and 3) establishing relevant quality indicators to measure outcomes of providing integrated COPC. Each of these challenges is described below in more detail.

Challenges and Opportunities of Successful Models

Overcoming Gate-Keeping

A common challenge that most programs have or will face is resistance to referral to palliative care by oncologists who are concerned that a referral to palliative care will mean the end of cancer treatment and a loss of patients’ hope, both of which may be counter to the ‘curative’ philosophy that many patients have when they go to a cancer center.47–49 Furthermore, even oncologists who believe in the supportive care available from palliative care specialists may fear that they will lose control or contact with their patients and patients will feel ‘abandoned’ by the oncology care team.50 Hence, some oncology clinicians may use ‘gate-keeping’ to prevent their patients from being referred to COPC, especially early in the diagnosis when ‘active’ cancer treatments are still being explored.

A number of innovative approaches can overcome clinician gate-keeping. Initiating palliative care in the outpatient setting as recommended by the NCP and NFQ10, 18 is one strategy that has been used to overcome negative biases that palliative care is only appropriate at EOL or after all other anti-cancer or disease-focused treatments are exhausted. Hui et al.32 reported that while the majority of cancer centers reported a palliative care presence, less than half had an outpatient component to care. They pointed out that because oncology care is provided primarily on an outpatient basis, the lack of outpatient palliative care could decrease referrals, coordination of care, and communication among clinicians.

Placing palliative care services within the geographical region of the oncology clinic, when feasible, provides real time collaboration on mutual patients and ongoing opportunity for palliative care education with attending physicians, medical and nursing students, residents, and fellows. Having geographic presence begins to normalize COPC, and has the added potential benefit of having palliative care appointments in tandem with oncology or chemotherapy appointments. This patient-centered approach to care is particularly valuable for patients who travel some distance for appointments.

Another challenge related to ‘gate-keeping’ is the name “palliative care”. Fadul and colleagues21 examined clinician comfort with referring to a palliative care versus a supportive care service. They found that there was more reported distress from providers and perceived distress from patients when the word “palliative” was used to describe the services, particularly when referrals were made early in disease trajectory. There was less of an issue when the referral was clearly for EOL care. An important issue is to determine if the name “palliative care” is a barrier to service use; if so, proactive and intentional education with colleagues and patients will be essential. One way the authors’ developing service dealt with this challenge was to focus first on describing the available services rather than on the term “palliative” that is, upon introduction to clinicians or patients the team described its role as ‘consultants to oncologists… that assist in the care of patients and families facing serious illness’. The team tells these individuals that it has a ‘focus on symptom management, comfort and quality of life, and can assist patients and families with complex decision making’.

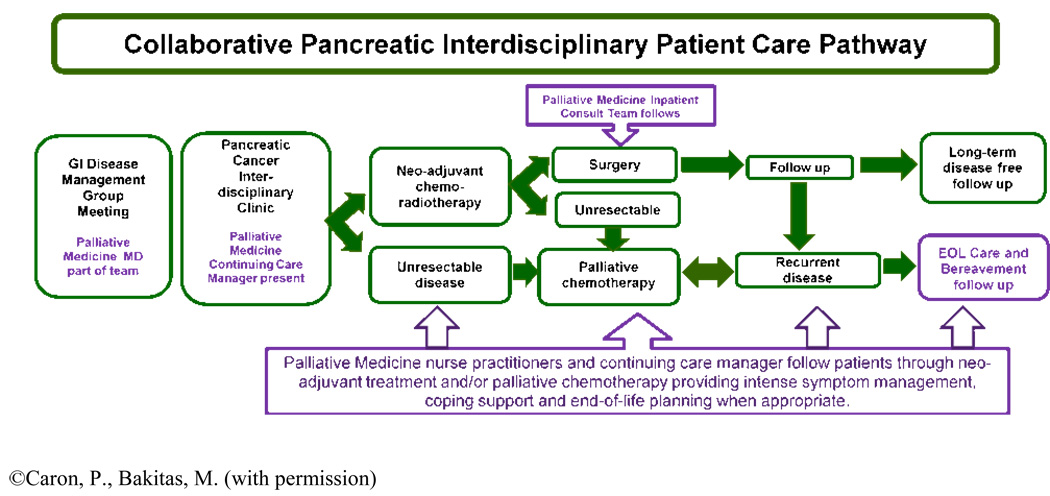

Processes such as implementing a standardized care pathway or disease specific algorithm which includes palliative care consultation ensures that appropriate services are introduced to virtually all appropriate patients as part of a systematic protocol rather than at the discretion of individual clinicians.51 Currently at NCCC, the diagnoses of pancreatic cancer, stage IIIB or IV non-small cell lung cancer, extensive stage small cell lung cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme trigger an automatic referral for an introductory palliative care outpatient appointment that is initiated by the scheduling secretary following the patient’s presentation at the disease-specific tumor board (see Figure 2). Another specific trigger for referral could be offering COPC to all patients enrolled in Phase I or II clinical trials.19, 52, 53

Figure 2.

Integrated Concurrent Oncology Palliative Care Pathway

Incorporating a Palliative Care Team (PCT) referral as part of the treatment team up front minimizes the resistance to referral later when ‘there’s nothing left to be done’. Early integration normalizes palliative care involvement and begins the process of building relationships before a crisis occurs, i.e., when patients are functioning well enough to be home and out in the community. Many palliative care issues can be better addressed prior to functional status decline. For example, studies have shown decision making around advance care planning is much less threatening when patients are feeling well,54 rather than during an inpatient crisis or when death is imminent. Psycho-emotional issues can be explored with greater ease when physical symptoms are controlled. Seemingly simple matters such as having a first meeting with the patient while he or she is in street clothes and returning home later that day may lend itself to a safer, more expansive and comprehensive experience.

To overcome gate-keeping due to clinician concerns about losing contact with patients or patients feeling abandoned, palliative care providers must maintain excellent and open lines of communication. Some electronic medical record (EMR) systems may provide a relatively simple solution to this issue. For example, using the EMR, a palliative care provider can instantly send notes to the patient’s entire team of providers including the medical oncologist, primary care physician, surgeon, and radiation oncologist. As noted earlier, geographic proximity to the patient’s oncology team also fosters regular communication and nurtures collegial relationships. Participation and invitation to attend each discipline’s interdisciplinary team meetings is an additional strategy to build trusting relationships that will maintain open lines of referral to palliative care clinicians.

Providing Expert COPC Across Transitions of Care

According to Coleman,55 transitions of care is a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care within the same location. Seamless transitions are a key element of integrated, high quality COPC models. The NCP and NQF practices (See Tables 1 and 2) identify “continuity of care” as an important aspect of quality palliative care. The guidelines state that palliative care is integral to all healthcare delivery system settings (hospital, emergency department, nursing home, home care, assisted living facilities, outpatient, and nontraditional environments, such as schools). Table 4 provides an example of how a newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer patient might experience smooth transitions of care using a COPC approach compared to common usual oncology care.

Table 4.

How a Concurrent Oncology Palliative Care Programs Might Influence “Usual Care” for Advanced Cancer Patients and their Families

| “Usual” Care | Care Process with a COPC |

|---|---|

| Patient is diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer and meets with oncologist. Treatment plan is developed and explained to patient/caregiver in detail. Expected side effects of treatment plan reviewed. |

Patient is diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer and meets with oncologist. Patient meets criteria (eg newly diagnosed IIIB or IV lung cancer) and is also referred for initial outpatient Palliative Care Team (PCT) Consultation and standardized holistic assessment

|

| Overwhelmed caregiver calls oncology regarding symptoms and is directed to ED with subsequent admission. |

Patient develops anticipated disease and/or chemotherapy-related symptoms/side effects and caregiver contacts PCT staff by phone. Instructed to come to clinic for evaluation. Caregiver anxiety previously identified, addressed and psychosocial PCTmembers consulted for ongoing support. |

| Inpatient / hospitalist medical team continues diagnostic workup |

Patient requires brief, planned hospital admit for symptom relief; continuity of care ensured by preplanned inpatient PCT follow up over hospitalization, including management of caregiver needs. |

| Patient undergoes tests and procedures. Symptom management per medical team. Patient and caregiver feel overwhelmed when a DNR discussion is broached by intern staff. Tension develops between the team and patient who asks ‘am I dying? Why are they giving up on me?’. |

PCT assists with symptom assessment and management including recommendations for palliative symptom interventions. Goals of care addressed in an ongoing fashion to assure interventions match patient/family goals. Advance Care Planning discussions that happened at diagnosis are reviewed. If patient is approaching end of life, desired place of death is identified with patient and caregivers and plans for final days are carefully crafted for optimum patient comfort. |

| Patient’s disease process is not able to be reversed. Patient develops acute deterioration and is transferred to the intensive care unit on ventilator. |

Discharge plan coordinated by inpatient PCT for patient to have home care (or hospice care) as needed. If death is imminent, standardized Comfort Measures Order Set is implemented. |

| After prolonged stay, patient dies in hospital. Family is in shock, feeling unprepared for death. |

Patient dies in preferred site of death. Bereavement care offered to family after the death |

Many challenges exist to providing quality transitions of care for palliative oncology patients and their families. Patients require complex continuous management as they have many symptoms related to the disease or to the treatment of the disease. They may experience heightened vulnerability during care transitions and frequently require care from multiple specialists. Thus, communication of their goals of care, medications, etc, can easily “fall through the cracks”.55–57 For example, when a symptomatic patient presents to an emergency department, emergency care providers may focus only on life-saving interventions rather than symptom control. They may not take the time to discuss the patient’s goals and preferences. This can result in patients receiving unwanted diagnostics, interventions, or hospital admissions.

Other challenges include communication difficulties that are inherent in caring for oncology patients with multiple oncology specialists (such as surgeons, and medical and radiation oncologists) and primary care providers in the community.58 Rural settings and regional cancer centers who collaborate with multiple visiting nurse associations and community hospitals present unique challenges to smooth patient hand-offs. Specifically, continuity of care is difficult to maintain when patients live at a distance from the treatment center, when there are few palliative care resources in local communities, when there is variable clinical expertise in rural communities, and when there are high turnover rates of nursing and medical personnel. These high turnover rates make it difficult for cancer center-based palliative care teams to build and maintain relationships with community providers. This situation may also signal inadequate experience or palliative oncology expertise in the community which will require both immediate and long-term education and consultation to ensure that the patient and family receive the same level of palliative care services at home as they receive in the tertiary center.

Integral structures to assure continuity of care across settings include an accountable care manager or care coordinator with palliative care expertise and written plans of care that are ‘portable’ and communicated across settings.25, 55, 57 The accountable team coordinator collaborates with professional and informal caregivers in each location of care to ensure coordination, communication, and continuity of palliative care across institutional and homecare settings. Maintaining regular contact by phone, between oncology appointments with patients who are at a distance from the cancer center, may also be accomplished via telephone using the skills of a palliative care specialist triage nurse. Typical triage nurse responsibilities can include prescription refills and pre-authorizations, general symptom evaluation, medication management, on-going education about the disease, treatments, and assistance with communication to community providers including hospice. Calls to patients 1–2 days prior to clinic appointments to review symptoms can help identify patient/family needs prepare patients and clinicians for an efficient, effective visit. Although input is primarily via the telephone, providing occasional opportunities for the triage nurse to participate in outpatient care, may enhance future telephone interactions.

Regardless of care location or level, the advanced cancer patient’s care should be based on a comprehensive care plan that is available to all providers so that the patient’s goals, preferences and clinical status are well-communicated.57 Components of the transitional care plan include logistical arrangements such as getting to the clinic, advance care planning preferences, patient and family education, and coordination among the health professionals involved in the transition. A primary area of attention is proactive management to prevent or address care desired in the event of crises and the avoidance of unnecessary transfers. An essential element of the documented care plan is documentation of the patient’s values and preferences for care in the form of an advance directive or advanced care planning note. This information must be readily accessible to all members of the medical team. This note can communicate the patient’s wishes regarding a surrogate medical decisions maker, preferences for specific life-prolonging treatments, and code status. Additionally, a checklist can be used when transitioning a patient from hospital to home hospice, which will remind the discharging team of certain important steps to providing a smooth transition to home and to the care of the hospice team and primary care clinician. With the patients’ goals and preferences in mind, items that are necessary to check off as completed include medications for crisis management, ensuring that the pharmacy carries the prescribed medications, verifying who will be overseeing the patient’s medical care at home, identifying who the patient will call in a crisis, and electronically sending the palliative care consultation.

Maintaining continuity when a crisis occurs is particularly challenging, but is also one of the most important times for the patient to have the attention of familiar care providers. The authors’ program found a creative way to do this by developing an automated system that notifies the PCT that a patient from the outpatient setting has been admitted to the hospital. This type of automated system allows for patients to have continuity across care settings and fosters communication of the patient’s goals, preferences, medications and clinical status during the hand-off from the outpatient team to the inpatient team. This system, called the “outs who are in” program was developed to provide continuity of care across settings. During the morning interdisciplinary meeting, these patients are identified through a tracking system in the EMR and the team is notified of their admission. The patient’s clinical status and goals are discussed and these patients are then added to the inpatient team consult list. Team consultation may range from supportive care visits from the team chaplain, to attention from the social worker, healing arts practitioner, or volunteers. However, some patients will also require expert communication and consultation for symptom management or integrating known preferences for care into the inpatient and discharge care plans.

Measuring Program Successes

Once a COPC program is in place another on-going challenge is to continuously measure and demonstrate program outcomes that are valuable to patients, families, administrators, and insurers. Demonstration of value added may be needed to secure initial or ongoing funding of a new palliative care clinical program. Every program should have a plan to measure and monitor its effect on the quality of patient care, ideally beginning prior to and then at the inception of the new program. Some measures will be useful for internal planning for staffing, need for program growth, and productivity. These same measures could then be compared to other programs as external benchmarks, especially for newer programs under development. Ultimately the data collected can be used to assure that high quality palliative care is provided across organizations.59

A number of frameworks exist that provide a foundation for assessing quality indicators in palliative care.60 10, 61, 62 Table 5 summarizes four key areas to consider in determining important metrics to continuously or intermittently monitor selected outcomes. Since the publication of NCP guidelines and NQF preferred practices (see Tables 2 and 3) consensus is building regarding essential domains and outcomes to measure different aspects of program evaluation. Although a comprehensive discussion of recommended metrics is beyond the scope of this paper, the reader is directed to recently published consensus recommendations to measure hospital-based palliative care programs24, consultation services,59, inpatient units,63, and clinical care and patient satisfaction.64

Table 5.

Metric Categories

| Metric Domain | Examples |

|---|---|

| Operational | Patient Demographics (Diagnosis, age, gender, ethnicity) referring clinician, disposition, hospital length of stay |

| Clinical | Symptom scores, psychosocial symptom assessment |

| Customer (Patient, Family, Referring Clinicians) |

Patient, family, referring clinician satisfaction surveys |

| Financial | Costs (pre- and post- HBPC consultation), inpatient palliative unit, net loss/gain for inpatient deaths |

Data from: 62

Measuring cost outcomes or cost effectiveness may also be a critical feature of program evaluation. The cost savings or ‘cost avoidance’ due to involvement of the palliative care team, especially in complex cases, is important, but can be more difficult to quantify and measure than direct revenue for services performed. While clinicians are tempted to proffer anecdotes of cost savings by descriptions of clinical encounters, administrators are more interested in data demonstrating improved symptom management, reduced hospital days, consumer satisfaction or cost savings generated by rational use of resources. As stated in a recent review of this topic, “Programs need to be able to demonstrate that they are providing value, and data provide a means of doing that.” 65 (p. 544) Recent reviews of palliative care influences on costs provide examples of how COPC programs may wish to evaluate their comparative effectiveness66–68

Three important challenges in measuring palliative care outcomes are: 1) whose perspective should be captured?, 2) who will do the ‘measuring’?, and 3) are there appropriate tools that are reliable and valid to capture data that will be meaningful? Data sources include patients, proxies (i.e., family caregivers), clinicians, and administrative data bases. Each has pros and cons to consider that should relate specifically to the question to be answered. Measuring outcomes can be costly in terms of staff time or identifying non-staff interviewers, chart auditors, or other data collectors. This is perhaps one of the bigger barriers to all programs having an active measurement component. Finally, although many tools have been developed and used in research, clinically meaningful tools for gathering data from patients who are seriously ill are only beginning to be developed and there is more controversy than consensus.12, 69–71

Although measurement of outcomes for program evaluation and quality improvement are important, continued development of rigor in measuring outcomes in the oncology palliative care research settings will ultimately provide the evidence base to ensure that palliative care will continue to flourish in the era of health care reform and limited financial resources. Health services researchers and others with expertise in measurement of palliative care outcomes are equally essential to the interdisciplinary team in managing the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer and their families.

Conclusion

It is clear that the specialties of oncology and palliative care each provide unique contributions to the care of patients with advanced cancer.52 There are increasing examples of successful programs that offer early and integrated care to this population. However, new and existing programs will continue to face the challenges of identifying and intervening early in the disease trajectory, using effective interdisciplinary team approaches that match the unique challenges of geography, culture, and available expertise and resources. Foundational resources are now available in the form of consensus guidelines and measurement practices so that future oncology patients and their families can be assured that they will have access to high quality care regardless of the length of their survivorship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynn J, Adamson D. Living well at the end of life: Adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. Santa Monica, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2008;56:593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Kaasa S. Quality of life in palliative cancer care: results from a cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3884–3894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno J, Clarridge BR, Casey VA, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell BR. Late referrals to palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:908–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapo J, Harrold J, Carroll J, Rickerson E, Cassarrett D. Are we referring patients to hospice too late? Patients' and families' opinions. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:521–527. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley KM, Gelband H. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Consensus Project. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care; Second Edition. Brooklyn, NY: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care. Geneva: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakitas M, Ahles T, Skalla K, et al. Proxy perspectives regarding end-of-life care for persons with cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1854–1861. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakitas M, Lyons K, Hegel M, et al. Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: Baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:75–86. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higginson I, Finlay I, Goodwin D, et al. Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;23:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, et al. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J pain symptom manage. 2003;25:150–168. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teno J, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Welte T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: A national study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, Spence C, Rhodes R, Connor S. Timing of Referral to Hospice and Quality of Care: Length of Stay and Bereaved Family Members' Perceptions of the Timing of Hospice Referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007/8 2007;34(2):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Quality Forum. A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers F, Linder J, Beckett L, Christensen S, Blais J, Gandara D. Simultaneous care: a model approach to the perceived conflict between investigational therapy and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Management. 2004;28(6):548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers F, Linder J. Simultaneous care: Disease treatment and palliative care throughout illness. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1412–1415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What's in a name? Cancer. 2009;115(9):2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant M, Hanson J, Mullan P, Spolum M, Ferrell B. Disseminating End-of-Life Education to Cancer Centers: Overview of Program and of Evaluation. J Cancer Education. 2007;22(3):140–148. doi: 10.1007/BF03174326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier DE, Spragens LH, Sutton S. A Guide to Building a Hospital-Based Palliative Care Program. New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Operational Features for Hospital Palliative Care Programs: Consensus Recommendations. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11:1189–1194. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byock I, Twohig JS, Merriman M, Collins K. Promoting excellence in end-of-life care: a report on innovative models of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:137–151. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robert Wood Johnson. Pioneer programs in palliative care: Nine case studies. New York, NY: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schapiro R, Byock I, Parker S, Twohig JS. Living and dying well with cancer: Successfully integrating palliative care and cancer treatment. Missoula, MT: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakitas M, Stevens M, Ahles T, et al. Project ENABLE: A palliative care demonstration project for advanced cancer patients in three settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:363–372. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esper P, Hampton J, Finn J, Smith D, Regiani S, Pienta K. A new concept in cancer care: the supportive care program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1999;16:713–722. doi: 10.1177/104990919901600608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Palliative Care V.I.2006, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. New York: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahles T, Seville J, Wasson J, et al. Panel-based pain managment in primary care: A pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:584–590. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasson J, Splaine M, Bazos D, Fisher E. Working inside, outside, and side by side to improve the quality of health care. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:513–517. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakitas M, Lyons K, Hegel M, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald N. Palliative care-the fourth phase of cancer prevention. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 1991;15:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald N. The interface between oncology and palliative medicine. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, MacDonald N, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner E. Collaborative managment of chronic illness. An Internal Med. 1997;127:1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner EH, Austin BTCD, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner E. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glasgow R, Emont S, Miller DC. Assessing delivery of the five 'As' for patient-centered counseling. Health Promotion International. 2006;21:245–255. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glasgow R, Whitesides H, Nelson C, King D. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2655–2661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner E, Bennett S, Austin B, Greene S, Schaefer J, Von Korff M. Finding common ground: Patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2005;(11) Supplement 1:S7–S15. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbeil Y, Byock I. Annual Assembly, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Vol. Boston, MA: 2010. Dying Badly at Home: Preventing and Managing Symptomatic Crises. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGrath P. End-of-life care for hematological malignancies: The 'technological imperative' and palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2002;18:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGrath P. Are we making progress? Not in hematology! Omega. 2002;45:331–348. doi: 10.2190/KU5Q-LL8M-FPPA-LT3W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hopkinson JB, Wright DN, Corner JL. Seeking new methodology for palliative care research: challenging assumptions about studying people who are approaching the end of life. Palliat Med. 2005;19:532–537. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1049oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S, Fayers PM, Ovreness T, Underland G, Ahlner-Elmqvist M. Challenges in palliative care research; recruitment, attrition and compliance: experience from a randomized controlled trial. Palliative Medicine. 1999;13:299–310. doi: 10.1191/026921699668963873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies B, Chekryn Reimer J, Brown P, Martens N. Challenges of conducting research in palliative care. Omega. 1995;31:263–273. doi: 10.2190/JX1K-AMYB-CCQX-NG2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bakitas M, Lyons K. Oncology clinicians' perspectives on providing palliative care for their patients with advanced cancer; 10th National Conference on Cancer Nursing Research Oncol Nurs Forum; 2009. p. 36. abstract 44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahluwalia S, Fried T. Physician factors associated with outpatient palliative care referral. Palliat Med. 2009;23:608–615. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Byock I. Palliative Care and Oncology: Growing Better Together. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:170–171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Byock I. Completing the continuum of cancer care: integrating life-prolongation and palliation. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:123–132. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Havens GAD. Differences in the execution/nonexecution of advance directives by community dwelling adults. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:319–333. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<319::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coleman E. Falling Through the Cracks: Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Transitional Care for Persons with Continuous Complex Care Needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meier DE, Beresford L. Palliative care's challenge: Facilitating transitions of care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:416–421. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:556–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Byock I. Principles of Palliative Medicine. In: Walsh D, editor. Palliative Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weissman DE, Meier DE, Spragens LH. Center to Advance Palliative Care Palliative Care Consultation Service Metrics: Consensus Recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1294–1298. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seow H, Snyder CF, Mularski RA, et al. A framework for assessing quality indicators for cancer care at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrell B, Paice J, Koczywas M. New standards and implications for improving the quality of supportive oncology practice. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3824–3831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elwyn G, Buetow S, Hibbard J, Wensing M. Measuring quality through performance. Respecting the subjective: quality measurement from the patient's perspective. BMJ. 2007;335(7628):1021–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39339.490301.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Center to Advance Palliative Care Inpatient Unit Operational Metrics: Consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:21–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weissman DE, Morrison RS, Meier DE. Center to Advance Palliative Care Palliative Care Clinical Care and Customer Satisfaction Metrics Consensus Recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:179–184. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meier DE, Beresford L. Using data to sustain and grow hospital palliative care programs. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:543–547. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas JS, Cassel JB. Cost and Non-Clinical Outcomes of Palliative Care. J pain symptom manage. 2009;38:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of Care Coordination on Hospitalization, Quality of Care, and Health Care Expenditures Among Medicare Beneficiaries: 15 Randomized Trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Internal Med. 2008;168:1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Twaddle M, Maxwell T, Cassel J, et al. Palliative care benchmarks from academic medical centers. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:86–98. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McNiff KK, Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, Eisenberg PD, Kadlubek P, Simone JV. Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: lessons learned from the quality oncology practice initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3832–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mularski RA, Rosenfeld K, Coons S, et al. Measuring outcomes in randomized prospective trials in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1S):S7–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]