Abstract

Background

Using the National Burn Repository (NBR), we sought to identify markers for injury severity and deep venous thrombosis (DVT) risk after electrical injury.

Methods

We identified adult patients in the NBR admitted with an electrical injury between 1995 and 2007 (n=1469). Patients who died within 24 hours or were admitted for less than 1 day and hospitals reporting no complications were excluded. Independent variables included total body surface area (TBSA) burned, duration of ICU stay and hospital admission, duration of mechanical ventilation, number of operative procedures, amputation, and early fasciotomy. Early fasciotomy was defined as fasciotomy performed on a patient’s first trip to the operating room and was used as a proxy for severity of electrical injury. Deep venous thrombosis and death were the dependent variables.

Results

Among electrically injured patients, 10.4% had early fasciotomy. Patients who had early fasciotomy had significantly prolonged ICU stays (10.3 days vs. 4.8 days, p<0.001), hospital days (36.7 days vs. 17.1 days, p<0.001), amputations (49.0% vs. 4.6%, p<0.001), and number of operative codes (17.6 vs. 5.4, p<0.001). DVT incidence was 0.9%. Electrically injured patients who had early fasciotomy were significantly more likely to have a DVT when compared to patients who did not have early fasciotomy (7.55% vs. 0.95%, p=0.002).

Conclusions

Early fasciotomy after electrical injury is a marker for increased injury severity. Among patients who have early fasciotomy after electrical injury, 7.5% develop DVT and 49% require amputation during their initial hospitalization.

INTRODUCTION

Electrical injuries represent a small proportion of the total burn injuries that occur in North America 1, 2. The mechanisms of thermal and electrical injury are inherently different. Thermal injury occurs from superficial to deep with the majority of injury apparent on clinical examination. By contrast, a large portion of electrical injury occurs from deep to superficial. Although soft tissue injury at the contact points may be detected on examination, deep tissue injury from electrical current may not be visible on initial clinical presentation.

Nerves and blood vessels have the lowest resistance to current. Conversely, bone has the highest resistance to current. Once in the body, current travels within nerves, within blood vessels, and along bones. Thus, electrical current is more likely to injure deep structures within the extremity. Following an electrical burn injury, typically there is injury to deep muscles leading to myonecrosis. Within 48 hours of the injury, the patient may experience a compartment syndrome related to the progressive myonecrosis and fluid resuscitation 3–5. The consequences of an untreated extremity compartment syndrome can range in severity from irreversible muscle damage to devastating destruction necessitating amputation. In order to prevent these complications of compartment syndrome, traditional management of severe extremity electrical injury includes early surgical exploration, fasciotomy, and debridement within 24 hours of injury 3.

Electrical injuries are the most devastating of all burn injuries, with cardiac, pulmonary, renal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic complications being common 4. Patients with electrical injury have multiple risk factors for deep venous thrombosis (DVT). These include increased ICU length of stay, number of operative procedures, and concomitant cutaneous burns 6–11. In addition, as blood vessels have low resistance to current flow (and are adjacent to high-resistance bone), direct electrical injury to vascular structures may increase DVT risk 3, 4, 12. In animal models, electricity is one of the techniques used to reproducibly create DVT 13, 14.

Using the National Burn Repository (NBR), we sought to identify markers for injury severity and DVT risk after electrical injury. We hypothesize that fasciotomy will be a proxy marker for increased injury severity, as evidenced by increased length of ICU stay and number of operative procedures. We further hypothesize that the fasciotomy will be associated with increased risk of deep venous thrombosis following an electrical burn injury.

METHODS

The American Burn Association’s National Burn Repository is a voluntary data set which compiles information from centers in the United States and Canada. The data set includes de-identified, HIPAA compliant, patient-level data which is also de-identified with respect to the burn center providing care. Data acquisition and entry is performed by trained chart reviewers. Reviewers identify eligible patients treated at their centers and collect data using a standardized format. Data is then uploaded to the NBR’s central data collection system. Patient-level data is acquired for demographics and medical comorbidities, etiology and extent of burn injury, ventilator days, ICU days, hospital length of stay, and patient disposition. Additionally, ICD-9 procedural codes are captured for both bedside and operative procedures. Over 100 complications are recorded in the NBR. Complications must be supported by data from morbidity and mortality conference and confirmed by the institution’s burn surgery attending staff. The NBR has previously been described in detail 9, 15, 16.

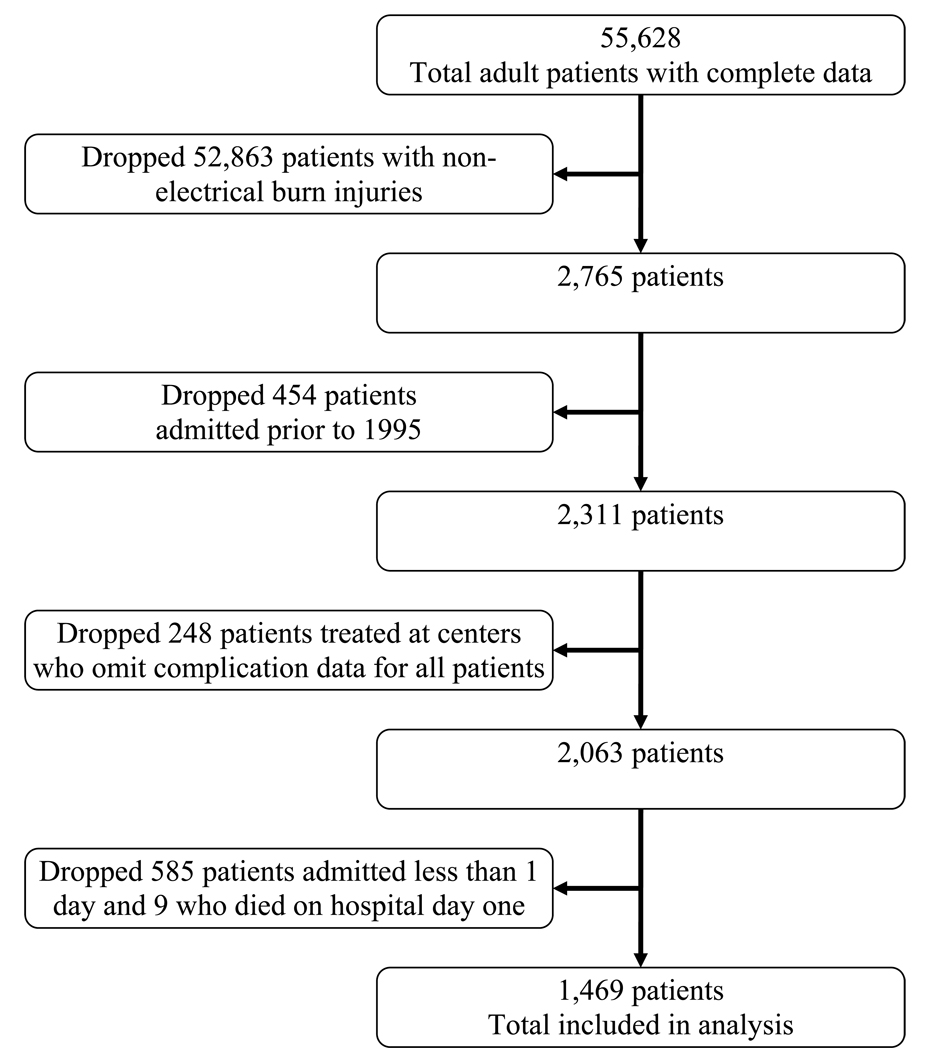

The NBR data set was kindly provided by the American Burn Association. Data sets were cleaned and merged using the Stata 11 statistical package (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). A graphic depiction of exclusion criteria is provided in Figure 1. Only patients with documented electrical injury were included in this analysis. Patients whose burn etiology was coded as electrical injury in addition to another type of burn (fire/flame, scald, etc) were also included.

Figure 1.

Study exclusion criteria

Independent variables for this analysis included age, gender, presence of medical comorbidites, total body surface area (TBSA) burned, duration of ICU admission, duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of hospital admission, number of operative procedures performed, amputation, and early fasciotomy.

The NBR identifies operative and bedside procedures via ICD-9 procedural codes. We identified non-digit amputations which involved the upper and lower extremites. Upper extremity amputations were identified using ICD-9 procedural codes 84.0, 84.00, and 84.03–84.09. Lower extremity amputations were identified using ICD-9 procedural codes 84.1, 84.10, and 84.12–84.19. Carpal tunnel release was identified using ICD-9 procedural code 04.43. Fasciotomy was identified using ICD-9 procedural codes 83.14 and 83.09. For study purposes, early fasciotomy was defined as fasciotomy which was performed on the patient’s first trip to the operating room. Data for patients who had fasciotomy was reviewed by hand to confirm timing of this procedure. The NBR does not include data on hospital day when a procedure was performed.

The NBR records both deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus (PE) among its list of complications. Additionally, we created a venous thromboembolism (VTE) variable which included patients with either DVT or PE. Death during initial hospitalization was identified as an additional dependent variable of interest. DVT, VTE, and death were utilized as our dependent variables in this analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata 11 statistical package. Descriptive statistics were generated to examine the incidence of DVT, PE, and VTE. Bivariate statistics were generated to identify any association between need for early fasciotomy and length of stay, number of ventilator days, number of operative codes, amputation, and death. Bivariate statistics were also performed to identify independent variables associated with DVT.

RESULTS

The data sets provided by the American Burn Association were merged, resulting in complete data for 55,628 burned patients whose age was ≥18. A total of 52,863 patients had non-electrical injuries and were dropped from the analysis. After several additional exclusions (Figure 1), a total of 1,469 electrically injured patients with length of stay ≥1 day were identified.

In electrically injured patients, the overall rate of DVT was 0.92% and PE was 0.20%. All patients with PE also had DVT. Thus, VTE incidence was 0.92%. In this series, 96% of electrical burn patients were male. Additionally, all VTE events occurred in male patients.

Fasciotomy was identified using ICD-9 procedural codes. Early fasciotomy, defined as fasciotomy performed during a patient’s first trip to the operating room, was confirmed using hand-review of data. Among electrically injured patients, 10.4% had early fasciotomy. Thirty-one percent of early fasciotomy patients had a concomitant ICD-9 procedural code for carpal tunnel release.

Early fasciotomy was associated with significantly increased number of ICU days (10.3 vs. 4.8, p<0.001), ventilator days (10.4 vs. 3.0, p<0.001), hospital days (35.7 vs. 17.1, p<0.001), and total number of operative codes (17.6 vs. 5.4, p<0.001) when compared to patients who did not have early fasciotomy. Early fasciotomy was also associated with significant increases in amputation (49.0% vs. 4.6%, p<0.001). Thus, early fasciotomy was associated with increased severity of injury. Early fasciotomy was not significantly associated with death (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate statistics examining early fasciotomy as a marker for illness severity

| Early Fasciotomy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Yes | No | p value |

| ICU days, mean | 10.3 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Ventilator days, mean | 10.4 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Hospital days, mean | 35.7 | 17.1 | <0.001 |

| Total number of operative codes, mean | 17.6 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Amputation during hospitalization, % | 49.0 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Death during hospitalization, % | 3.9% | 2.5% | 0.40 |

Early fasciotomy was used as a proxy marker for severity of electrical injury. Those patients who had early fasciotomy were at increased risk to develop DVT when compared to patients who did not have early fasciotomy (7.55% vs. 0.95%, p=0.002). The combination of early fasciotomy and increased TBSA was associated with increased DVT risk (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

DVT incidence in electrically injured patients stratified by TBSA burned and need for early fasciotomy. Thermal burn only data is provided for comparison and was performed during a prior analysis of the National Burn Repository 9.

* p<0.001, comparison of DVT rate between electrically injured patients with TBSA 0–20% and TBSA >20%

** p=0.002, comparison of DVT rate between electrically injured patients who required and did not require early fasciotomy

Using bivariate statistics, each additional percent TBSA burned (OR 1.05, p<0.001), need for ICU admission (OR 8.51, p=0.048), each additional ICU day (OR 1.04, p<0.001), each additional mechanical ventilation day (OR 1.04, p=0.01), each additional operative procedure (OR 1.14, p<0.001), and early fasciotomy (OR 8.52, p=0.002) were associated with significantly increased DVT risk. Each additional year of age and presence of ≥ 2 medical comorbidities were not significantly associated with DVT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate statistics examining risk factors for DVT

| Risk Factors | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (each year) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.465 |

| ≥ 2 medical comorbidities | 7.47 (0.88–63.27) | 0.065 |

| TBSA burned (each additional percent) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | <0.001 |

| TBSA burned 0–20% >20% |

Comparison 17.90 (3.68–86.94) |

--------- <0.001 |

| Admission to ICU | 8.51 (1.02–70.96) | 0.048 |

| Length of ICU admission (each additional day) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation >48 hours | 12.00 (2.82–51.09) | 0.001 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation (each additional day) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.01 |

| Operative procedure (each additional) | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | <0.001 |

| Early fasciotomy | 8.52 (2.22–32.78) | 0.002 |

DISCUSSION

After electrical injury, early fasciotomy is associated with significantly increased ICU and hospital length of stay, number of ventilator days, and number of operative procedures. Additionally, early fasciotomy is associated with a 10-fold increase in amputation (49.0% vs. 4.6%). Overall, 0.9% of patients with electrical injury develop DVT during their initial admission. This is 1.8 times higher than reported DVT rates from the NBR for thermally injured patients (0.48%) 9. Among the subset of patients who have early fasciotomy, DVT incidence increases to 7.5%. Bivariate statistics demonstrate that increased TBSA burned, increased length of ICU stay, increased number of ventilator days, increased number of operative procedures, and early fasciotomy were significantly associated with DVT.

Electrical injury is commonly used as a reliable, reproducible method to produce DVT in animal models. In mice, intraluminal thrombus can be seen within minutes of the electrical injury. Intraluminal clot will reliably form with electrical stimuli applied from within (to the endothelium) or from without (to the vein wall) 13. In rabbit models, angiogram evidence of electricity-induced vessel injury is seen within 15 minutes; damage progresses over the first 48 hours 14. In animal models, there is a clearly defined association between electrical injury and DVT.

In several clinical case studies, there has also been an association identified between electrical injury and venous thrombosis. Thrombosis of subcutaneous 17, axial 18, 19, central 18, 20, and intracerebral 21 veins have been reported to occur after electrical injury. The clinical presentation of thrombosis can occur within 30 minutes, though in some cases clinical presentation was delayed by several weeks. An additional case report discusses a low voltage electrical injury in a woman at 34 weeks gestation. The child was delivered for fetal distress at 36 weeks gestation and a thrombosis was identified in the child’s renal vein 22. While these case reports document a temporal relationship between an electrical injury and venous thrombosis, causality has clearly not been demonstrated.

The association between electrical injury and vein damage has also been noted in the reconstructive surgery literature. In a series of patients who required free flap upper extremity reconstruction, flap success rate was notably different between electrically injured versus non-electrically injured patients (81% versus 97%). The authors conclude that “in high voltage electric injuries, higher [vein thrombosis] rates should be expected because of possible recipient vessel injuries” 23.

The mechanism by which electrical injury may cause DVT remains unclear. Using a retrospective analysis of a large database, we cannot provide a causal mechanism. However, our analysis indicates that patients who have early fasciotomy are at significantly increased DVT risk. Two hypotheses may explain this phenomenon. Early fasciotomy indicates a more severe electrical injury, as evidenced by significantly increased ICU length of stay, ventilator days, amputations, and number of operative procedures. In thermally injured patients, increased TBSA burned, number of ICU days, and number of procedural codes were independently associated with significantly increased VTE risk 9. Additionally, the severe electrical injury passes along bone, causing direct injury to deep structures, including the axial veins. Subsequent increased intra-compartment pressure may indirectly impede venous outflow and cause venous stasis. The resultant venous dilation can cause intimal microtears which activates the local clotting cascade 24. Through both direct and indirect effects on the vein wall, electrical injury may predispose to DVT.

Limitations

The clinical management of electrically injured patients 3, 4 and the physics of electrical injury 5 are well discussed elsewhere and are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

We have previously discussed NBR limitations for an examination of VTE after thermal injury 9. However, our analysis of deep venous thrombosis after electrical injury has several additional limitations which deserve mention.

Operations are numbered sequentially in the NBR. Within each operation number, multiple ICD-9 procedural codes can be entered. The NBR also contains an “OR Visit Number” variable. Unfortunately, one third of these data were coded as missing or invalid, limiting the utility of this variable. To maximize capture of early fasciotomy events, we performed a hand-review of operative codes to determine when the procedures were performed.

The NBR contains data on the location of injury (extremity, trunk, head, etc). However, procedural codes are not linked to a variable which specifies operative location. The combination (present in 31% of early fasciotomy patients) of ICD-9 procedural codes for fasciotomy and carpal tunnel release can be used as a proxy for upper extremity fasciotomy. However, this coding scheme would misclassify patients who had upper extremity fasciotomy without carpal tunnel release. Similarly, although deep venous thrombosis is recorded as a complication, no information is available on upper vs. lower extremity or left vs. right. Thus, based on clinical judgment and experience, we can only infer that deep venous thrombosis events may have occurred in the extremity injured by electricity. Additionally, we were unable to verify findings by Wahl et al, published in 2002, that DVT is more common in a thermally burned vs. non-thermally burned extremity 25.

Electrical injuries represent a small proportion of burn injuries seen at referral centers 1, 2, 26 and represent 2.6% of all patients in the NBR. Similarly, DVT occurs in 1% of electrically injured patients and is thus a rare event. Unfortunately, too few DVT events were present among electrically injured NBR patients to perform multivariable regression analysis. Use of multivariable regression with a paucity of outcome events violates the basic assumptions of regression and may provide inaccurate, potentially misleading results. Although our analysis plan had called for multivariable regression, these data cannot be provided in a statistically robust fashion. Thus, our manuscript is a descriptive paper with several stratified analyses.

In a recent “Glimmer” publication 27, Jeng et al recommend that investigators design an NBR analysis around a “watershed event” in burn prevention or care. One potential “watershed event” relevant to this study includes recent recommendations for screening duplex ultrasound of high risk patients in burn intensive care units 25, 28. To facilitate such an analysis in both thermally and electrically injured patients, future versions of the NBR should include discrete variables on imaging method used for DVT diagnosis, whether the DVT was symptomatic or asymptomatic, hospital day on which the diagnosis was made, as well as type and duration of chemoprophylaxis provided prior to the event.

The NBR contains no data on whether chemoprophylaxis was provided. Thus, we cannot make recommendations on the utility of chemoprophylaxis for VTE prevention after electrical injury. However, electrically injured patients who had early fasciotomy have a significantly higher DVT rate (7.55% vs. 0.95%, p=0.002) than those patients who did not have early fasciotomy. These patients represent a high-risk subgroup for whom aggressive VTE prophylaxis should be considered.

CONCLUSION

Early fasciotomy after electrical injury is associated with significantly increased number of ICU days, ventilator days, hospital days, and total number of operative codes. Thus, early fasciotomy is a marker for increased severity of injury. Patients who have early fasciotomy after electrical injury are at over 7-fold increased risk (7.55% vs. 0.95%) for DVT and over 10-fold increased risk (49.0% vs. 4.6%) for amputation during their initial hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support

Dr. Pannucci receives salary support through NIH grant T32 GM-08616.

Dr. Osborne is a current Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

CJ Pannucci, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

NH Osborne, Michigan Surgical Collaborative for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

RM Jaber, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

PS Cederna, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

WL Wahl, Division of Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.DeKoning EP, Hakenewerth A, Platts-Mills TF, Tintinalli JE. Epidemiology of burn injuries presenting to North Carolina emergency departments in 2006–2007. Burns. 2009;35:776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SF, Bessey P, Lentz CW, et al. National Burn Repository 2007 report: A synopsis of the 2007 call for data. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:862–870. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818cb046. discussion 871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnoldo B, Klein M, Gibran NS. Practice guidelines for the management of electrical injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:439–447. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000226250.26567.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF. The diagnosis and management of electrical injuries. Hand Clin. 2009;25:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fish RM, Geddes LA. Conduction of electrical current to and through the human body: A review. Eplasty. 2009;9:e44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KK, Blackbourne LH, Renz EM, et al. Global evacuation of burn patients does not increase the incidence of venous thromboembolic complications. J Trauma. 2008;65:19–24. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181271b8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fecher AM, O'Mara MS, Goldfarb IW, et al. Analysis of deep vein thrombosis in burn patients. Burns. 2004;30:591–593. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrington DT, Mozingo DW, Cancio L, Bird P, Jordan B, Goodwin CW. Thermally injured patients are at significant risk for thromboembolic complications. J Trauma. 2001;50:495–499. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pannucci CJ, Osborne NH, Wahl WL. Venous thromboembolism in thermally injured patients: analysis of the national burn repository. J Burn Care Res. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318204b2ff. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprini JA. Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon. 2005;51:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133:381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt JL, McManus WF, Haney WP, Pruitt BA., Jr Vascular lesions in acute electric injuries. J Trauma. 1974;14:461–473. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooley BC, Szema L, Chen CY, et al. A murine model of deep venous thrombosis: Characterization and validation in transgenic mice. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:498–503. doi: 10.1160/TH05-03-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus HM, Hutto W. Electric burns and frostbite: Patterns of vascular injury. J Trauma. 1982;22:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latenser BA, Miller SF, Bessey PQ, et al. National Burn Repository 2006: A ten-year review. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:635–658. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E31814B25B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeng JC. Advisory Committee to the National Burn Repository. "Open for business!" a primer on the scholarly use of the national burn repository. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:143–144. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31802cfabe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randell P. Mondor's disease and electrocution. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:75–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mocumbi AO. Deep-vein and intracardiac thrombosis of unclear aetiology: Possible association with intermittent low-voltage electrical trauma. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2009;20:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott JR, Klein MB, Gernsheimer T, Honari S, Gibbons J, Gibran NS. Arterial and venous complications of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:71–75. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013E31802C8929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masaki F, Isao T, Aya Y, Nakayama R, Tadaaki Y, Hideyosi T. Extensive thrombosis of the inferior vena cava and portal vein following electrical injury. Burns. 2005;31:660–664. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel A, Lo R. Electric injury with cerebral venous thrombosis. Case report and review of the literature. Stroke. 1993;24:903–905. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anguenot JL. Antenatal renal vein thrombosis after accidental electric shock in a pregnant woman. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18:779–781. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.11.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akinci M, Ay S, Kamiloglu S, Ercetin O. Lateral arm free flaps in the defects of the upper extremity--a review of 72 cases. Hand Surg. 2005;10:177–185. doi: 10.1142/S0218810405002784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comerota AJ, Stewart GJ, Alburger PD, Smalley K, White JV. Operative venodilation: A previously unsuspected factor in the cause of postoperative deep vein thrombosis. Surgery. 1989;106:301–308. discussion 308–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahl WL, Brandt MM, Ahrns KS, et al. Venous thrombosis incidence in burn patients: Preliminary results of a prospective study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:97–102. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao J, Cai BR. A clinical study of electrical injuries. Burns. 1994;20:340–346. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeng JC, Parks J, Phillips BL. Warding off burn injuries, warding off database fishing expeditions: The ABA burn prevention committee takes a turn with a glimmer from the National Burn Repository. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:433–434. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31817108c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wibbenmeyer LA, Hoballah JJ, Amelon MJ, et al. The prevalence of venous thromboembolism of the lower extremity among thermally injured patients determined by duplex sonography. J Trauma. 2003;55:1162–1167. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000057149.42968.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]