Abstract

Pancreatitis caused by activation of digestive zymogens in the exocrine pancreas is a serious chronic health problem in alcoholic patients. However, mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis remains obscure due to lack of a suitable animal model. Earlier, we reported pancreatic injury and substantial increases in endogenous formation of fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) in the pancreas of hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH)-deficient (ADH−) deer mice fed 4% ethanol. To understand the mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we evaluated dose-dependent metabolism of ethanol and related pancreatic injury in ADH− and hepatic ADH-normal (ADH+) deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol via Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet daily for 2 months. Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was remarkably increased and the concentration was ~1.5-fold greater in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. At the end of the experiment, remarkable increases in pancreatic FAEEs and significant pancreatic injury indicated by the presence of prominent perinuclear space, pyknotic nuclei, apoptotic bodies and dilation of glandular ER were found only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. This pancreatic injury was further supported by increased plasma lipase and pancreatic cathepsin B (a lysosomal hydrolase capable of activating trypsinogen), trypsinogen activation peptide (by-product of trypsinogen activation process) and glucose-regulated protein 78 (endoplasmic reticulum stress marker). These findings suggest that ADH-deficiency and high alcohol levels in the body are the key factors in ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Therefore, determining how this early stage of pancreatic injury advances to inflammation stage could be important for understanding the mechanism(s) of alcoholic pancreatitis.

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis, an inflammatory disorder, is a devastating disease primarily initiated by tissue autolysis of exocrine pancreas due to activated proteolytic (digestive) enzymes in the exocrine pancreas. Histological spectrum of alcoholic pancreatitis ranges from acute necrotizing inflammation (acute pancreatitis) to irreversible structural and functional destruction (chronic pancreatitis) of the gland (Lankisch and Banks, 1998; Witt et al., 2007). Alcoholic patients presenting their first attack of symptomatic pancreatitis usually exhibit elements of underlying chronic pancreatitis indicating a chronic nature of the disease (Singh and Simsek, 1990; Lankisch and Banks, 1998; Brunner et al., 2004). Ethanol exposure alters lipid metabolism and its homeostasis and causes fatty infiltration (steatosis) in the pancreas of experimental animals (Wilson et al., 1982; Simsek and Singh, 1990; Lopez et al., 1996). However, sequel of early events leading to inflammation in the gland is not well understood primarily due to lack of a suitable animal model (Schneider et al., 2002; Pandol and Raraty, 2007; Kaphalia, 2010). Therefore, developing a suitable animal model that reproduces key histological features (inflammation and fibrosis) and for understanding the mechanism(s) of alcoholic pancreatitis are important for its early prevention and reversal.

Majority of ingested ethanol (~90%) is metabolized by hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to acetaldehyde, which is further metabolized to acetate by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) at the rate it is formed (Rognstad and Grunnet, 1979). Substantial inhibition of hepatic ADH and/or ALDH is reported in chronic alcoholics (Nuutinen et al., 1983; Kershengol’ts et al., 1985; Palmer and Jenkins, 1985; Panes et al., 1989, 1993). Hepatic ADH is also inhibited in vitro, in vivo after ethanol exposure in laboratory animals and even during early stage of fatty liver in alcoholics (Shore and Theorell, 1966; Baker et al., 1973; Zahlten et al., 1980; Thomas et al., 1982; Sharkawi, 1984; Kaphalia et al., 1996; Ciuclan et al., 2010). Ethanol exposure to rats fed 4-methylpyrazole (hepatic ADH inhibitor) is shown to increase formation of fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs, nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol) by several folds and cause pancreatitis-like injury (Manautou and Carlson, 1991; Werner et al., 2002). Metabolism of ethanol via nonoxidative pathway to FAEEs (catalyzed by FAEE synthase) is suggested to be a major pathway for ethanol disposition in the pancreas frequently damaged during chronic alcohol abuse (Laposata and Lange, 1986; Kaphalia et al., 2004). Due to abundant FAEE synthase found in the mammalian pancreas and the lipophilic nature of FAEEs, greater amounts of FAEEs are formed and accumulated in the pancreas (Laposata and Lange, 1986; Bhopale et al., 2006).

Among several oxidative and nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol (acetaldehyde, phosphatidylethanol, ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate), FAEEs are known to cause pancreatic toxicity, activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells and activator protein 1 (key regulators of the inflammation) and other pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (Gukovskaya et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2008; Petersen et al., 2009). Therefore, role of endogenously formed nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol in etiopathogenesis of alcoholic pancreatitis needs to be investigated.

In previous study, we reported substantial increases in FAEE formation, pancreatic injury and significant mortality in hepatic ADH-deficient (ADH−) vs. hepatic ADH-normal (ADH+) deer mice fed 4% ethanol for 2 months (Bhopale et al., 2006). In the present study, we determined dose-dependent metabolism of ethanol and associated pancreatic injury including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in deer mouse model to determine the metabolic basis and mechanism(s) of alcoholic pancreatitis.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

FAEEs from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and [1-14C] oleic acid (specific activity 56 mCi/mmol) from NEN (Boston, MA) were used. Monoclonal antibodies raised against synthetic peptide (KLH-coupled) derived from the sequence around Gly584 of human glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78 or BiP) and affinity purified goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA). Unless specified, all the chemicals, reagents and solvents used in the present study were from Sigma or Fisher Scientific, NJ.

Animal experiments

Hepatic ADH negative phenotype (ADH−) deer mice, a natural genetic variant of Peromyscus maniculatus, and ADH positive (ADH+) deer mice (male, ~1 year old, ~20g weight) obtained from Peromyscus Stock Center, University of South Carolina, Department of Biological Sciences, Columbia, SC were housed in UTMB’s Animal Resource Center. Considering an average life span of deer mice 4–5 years, one year age can be assumed equivalent to adult human age. After a mandatory 10 weeks quarantine as per institutional regulation, animals were acclimatized for additional one week. Animals were divided as control and experimental groups and the experimental group was fed Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA) for a week followed by 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol in the liquid diet (Bhopale et al., 2006). Control animals for each group were pair-fed liquid diets containing equivalent calories substituted by maltose-dextrin. At the end of 2 months of ethanol feeding, blood was withdrawn directly from the hearts of animals anesthetized with Nembutal™ and transferred to heparinized tubes. Fifty μL aliquot of whole blood was sampled in gas chromatograph (GC) autosampler vial for the analysis of blood alcohol and acetaldehyde levels (Wu et al., 2008). Remaining blood was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min and the plasma separated and stored at −80°C until the analysis.

Morphological studies

The pancreas was excised for gross examination and a portion was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining for the light microscopy (Bhopale et al., 2006). Selected sections of the pancreas were also stained with Masson Trichrome stain to examine fibrous tissue formation. Sections were also stained with antibodies raised against CD3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA) to determine inflammatory infiltrate and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) coupled with KLH in rabbits (Alpha Diagnostic Int., San Antonio, TX) to evaluate oxidative stress. After removal of unbound primary antibodies, the sections were incubated with followed by incubation with avidin and biotinylated horse radish peroxidase secondary antibodies. The color was developed by diaminobenzidine (Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc., CA). The images were captured with an Olympus IX71 microscope equipped with digital camera DP71 and OLYMPUS MICRO DP71, VER 03.01 software.

For examining ultrastructural changes, 1 – 3 mm pieces of pancreas were fixed in fixing buffer, stained and examined in a Philips 201 or CM100 electron microscope as described previously (Bhopale et al., 2006).

TUNEL assay

Apoptosis in paraffin-embedded thin sections of pancreas was determined by in situ end labeling using TdT-FragEL™ in situ apoptosis detection kit from Calbiochem® (QIA33, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Blood alcohol and acetaldehyde levels

The levels of blood alcohol and acetaldehyde were determined by head space GC as described previously (Wu et al., 2006, 2008).

Amylase and lipase assays

Plasma amylase and lipase were assayed using Biotron Diagnostics kits (Hemet, CA) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

FAEE synthase assay

Ethanol exposure is known to induce pancreatic FAEE synthase activity (Pfutzer et al., 2002). Therefore, pancreatic FAEE synthase was assayed using [1-14C] oleic acid as substrate (Kaphalia and Ansari, 2003).

Cathepsin B assay

Pancreatic lysosomal hydrolases such as cathepsin B, induced by ethanol exposure, can activate trypsinogen (Korsten et al., 1995). FAEEs are also known to increase the fragility of lysosomal membranes and release cathepsin B in the cytoplasmic compartment (Haber et al., 1993). Therefore, cytoplasmic cathepsin B was assayed using a Fluorogenic activity assay kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Protein was determined according to Lowry et al. (1951).

Quantitation of trypsinogen activation peptide

The activation of trypsinogen (one of the zymogens synthesized and stored in the pancreatic acinar cells) occurs in the proximal small intestine during digestion by a gut hormone, enterokinase, which releases trypsinogen activation peptide as a reaction byproduct (TAP, Rinderknecht, 1986). However, premature activation of trypsinogen within the acinar cells may release TAP in the pancreas and circulation. Previously, we found no appreciable change in plasma TAP of ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 4% ethanol for 2 months (Bhopale et al., 2006). Therefore, TAP was directly measured in the post nuclear fraction of pancreatic homogenate by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) developed in our laboratory (Wu et al., 2008).

Plasma and pancreatic lipids and FAEEs

Total lipid contents and FAEEs were determined in the plasma and pancreas of control and ethanol-fed deer mice as described earlier (Bhopale et al., 2006). In brief, extracted lipids were subjected to solid phase extraction to separate into neutral lipids and phospholipids. The neutral lipid fraction was dried under nitrogen and subjected to thin layer chromatography. The ester fraction was eluted and analyzed by GC and/or GC-mass spectrometry (Kaphalia et al., 2004; Bhopale et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2008). The recovery of internal standard was >70% and the data were corrected for the percent recovery. The values are expressed as mg/g and μg/g tissue (wet weight) for the lipids and FAEEs, respectively.

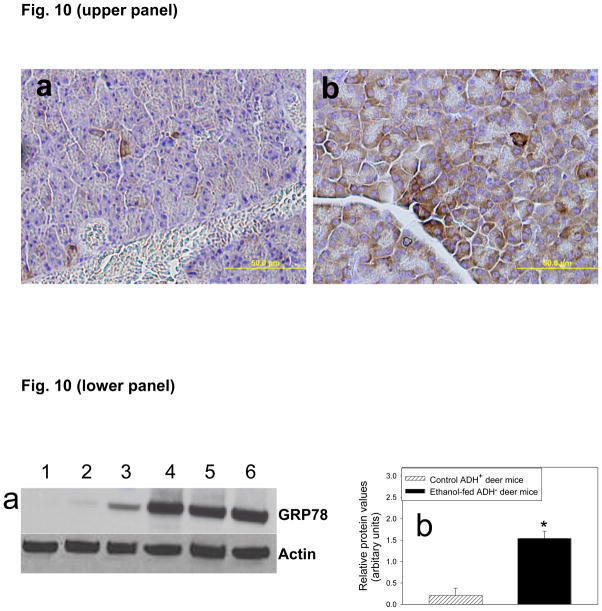

Characterization of endoplasmic reticulum stress

In view of our published results on ethanol-induced swelling of glandular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cisternae in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 4% ethanol for 2 months (Bhopale et al., 2006), we characterized ER stress by measuring glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78/BiP, marker of ER stress) in the pancreatic post nuclear fraction. The proteins were separated on polyacrylamide gels, transblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane for the Western blot analysis using antibodies against GRP78 (1:1000 dilution) and affinity purified HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit antibodies, and the relative band intensities determined as described earlier by Wu et al. (2008).

For immunohistochemical localization of GRP78 in the pancreas, paraffin-embedded thin sections (5 μm) were mounted on glass slides and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and antigen unmasking done by emerging the slides in boiling 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were cooled, washed with distilled water followed by incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide. After blocking, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies (1: 200 dilutions) overnight at 4°C and unbound primary antibodies were removed by washing with phosphate buffered saline. The sections were incubated with secondary antibodies followed by ABE avidin/biotin. Staining was done by diaminobenzidine and the images were captured with an Olympus IX71 microscope as described earlier.

Statistical analysis

The data sets were analyzed for statistical significance using Student t-test and ANOVA or Student-Newman-Keul’s multiple comparison test and p value <0.05 was considered significant. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean) of 5 animals per group unless indicated.

Results

Greater increases in BAC in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol resulted in substantial endogenous formation of FAEEs and injury in the pancreas including ER stress. BACs were found to be <10 mg% in both strains fed 1 or 2% ethanol. Irrespective of strain and doses of ethanol used in the present study, we found comparable levels of acetaldehyde, an oxidative metabolite of ethanol. Pancreatic injury assessed morphologically and by the injury markers suggest an early stage injury. However, the data presented herein suggest that hepatic ADH deficiency and dose of ethanol play critical role in ethanol-induced pancreatic injury.

BAC and blood acetaldehyde levels

The recovery of ethanol and acetaldehyde from the blood samples by head space GC analysis was found to be > 95%. Although BAC in ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol were far greater than those fed 1 or 2% ethanol, BAC increased ~1.5 fold in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. Average BACs were 3.9 vs. 2.9, 9.8 vs. 6.7 and 137.2 vs. 89.0 mg% in ADH− vs. ADH+ fed 1, 2 and 3.5% ethanol, respectively (Fig. 1). However, no statistical significance was found between the blood acetaldehyde levels in ethanol-fed ADH− and ADH+ deer mice at corresponding doses; average being 0.06 vs. 0.05, 0.09 vs. 0.17 and 0.24 vs. 0.34 mg% in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5 % ethanol, respectively. These results indicate that hepatic ADH-deficiency significantly increases BAC without any significant change in blood acetaldehyde levels.

Fig. 1.

BAC in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5). * - p value <0.05.

Lipids and FAEE levels in the plasma and pancreas

Plasma and pancreatic lipids

Total lipids in the plasma were significantly not altered between ethanol-fed vs. pair-fed control animals (data not shown). However, pancreatic lipids were significantly increased (~1.4 fold) only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol as compared to those in corresponding controls (Fig. 2). The levels were comparable among ADH− deer mice fed 1 or 2% ethanol, ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol and respective pair-fed controls (Fig. 2). Thus, hepatic ADH-deficiency appears to be a critical factor in ethanol-induced lipid metabolomic changes in the pancreas particularly at high ethanol doses.

Fig. 2.

Total lipids in the pancreas of ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5). * - p value <0.05.

Plasma and pancreatic FAEEs

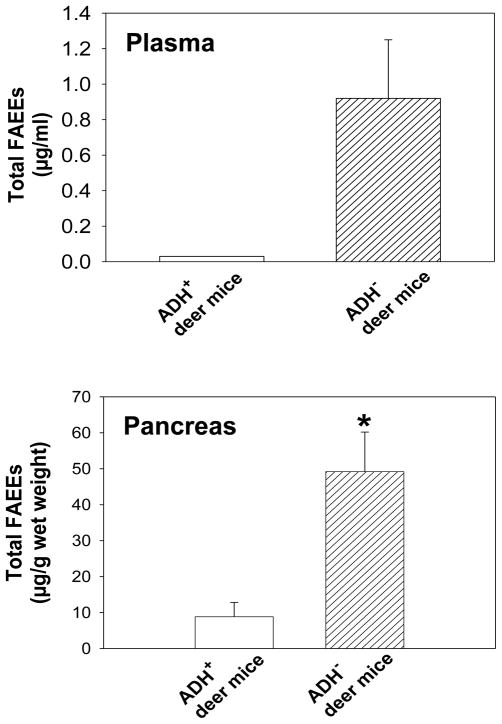

Average total plasma FAEEs was estimated to be 0.92 μg/ml in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol (Fig. 3); palmitic (16:0) and oleic (18:1) FAEEs being the major esters accounting >75% by weight (0.23 and 0.55 μg/ml, respectively). Stearic (18:0) and linoleic (18:2) FAEEs were detected in two and one out of four animals, respectively. Only one out of four ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol and ADH− deer mice fed 2% ethanol showed 16:0 and/or 18:1 FAEE residues. No detectable amounts of FAEEs were found in ADH− deer mice fed 1% ethanol or ADH+ deer mice fed 1 or 2% ethanol.

Fig. 3.

Total FAEE concentration in the plasma and pancreas of ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Values are mean ± SEM (n=4 for plasma, n=5 for pancreas). * - p value <0.05; p value for the plasma FAEEs could not be determined because only one out of four plasma samples of each ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol and pair-fed ADH− deer mice corresponding to 3.5% ethanol showed FAEE residues.

The FAEE levels in the pancreas were found to be ~6 fold greater in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol (Fig. 3). Two out of five pair-fed control ADH− deer mice corresponding to those fed 3.5% ethanol also contained 16:0 and 18:1 FAEEs. Two out of 5 each ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 2% ethanol showed FAEE residues in the pancreas. However, no FAEE residues were detected in either strain fed 1% ethanol or pair-fed controls (Fig. 3) of both strains corresponding to 1 or 2% ethanol doses. Average pancreatic total FAEEs were estimated to be 49.20 μg/g in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol vs. 2.38 μg/g in corresponding controls (Fig. 3). Average values for 16:0, 18:1, 18:2 and arachidonic (20:4) FAEEs in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol were found to be 4.55, 9.88, 21.40 and 12.80 μg/g (wet weights), respectively. Average total FAEE levels were found to be 8.64 μg/g in the pancreas of ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol vs. 2.27 μg/g in corresponding pair-fed controls. Our results indicate that the ethanol concentration in the body and hepatic ADH-deficiency are critical for the endogenous formation of FAEEs in the pancreas. The plasma FAEE levels truly reflect pancreatic FAEE levels in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol.

Morphological changes in the pancreas

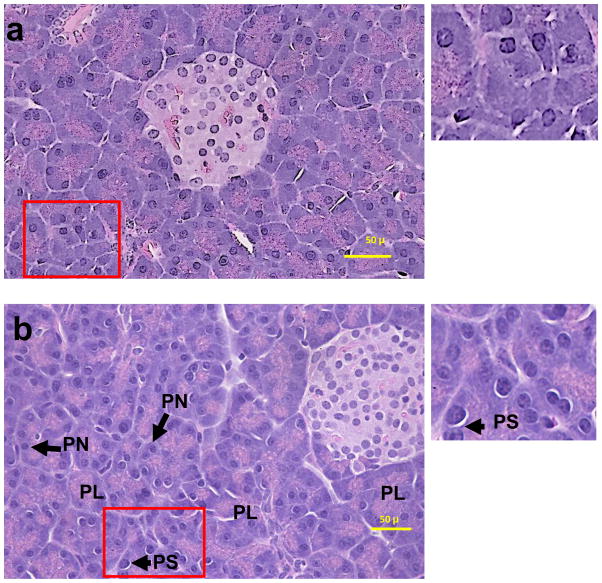

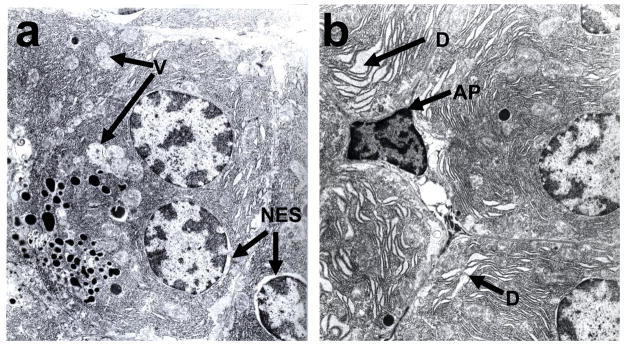

Pancreatic morphology was significantly altered only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. The changes include partial loss of acinar architecture, presence of prominent perinuclear space and pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 4). The fibrous tissue formation and inflammation response and oxidative stress were negative based upon lack of staining with trichrome, antibodies against CD3 and 4-HNE antibodies in ethanol-fed groups, respectively (data not shown). No significant changes were observed in ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol and both strains fed 1 or 2% ethanol. The ultrastructural changes observed in the pancreas of ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol include presence of apoptotic bodies, swelling of nuclear envelope, enlargement of intercellular spaces, and dilation and swelling of the glandular ER cisternae indicating ER stress (Fig. 5). The apoptosis was also confirmed by TUNEL assay (Fig. 6). However, ultrastructural changes, particularly, disintegration of granular ER and formation of multiple small vesicles were also observed in some acinar cells of ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol only (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

H & E stained pancreatic sections ADH+ (a) and ADH− (b) deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Histological changes are shown to be partial loss of acinar structure (PL), presence of perinuclear space (PS) and pyknotic nuclei (PN) only in the pancreas of ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol.

Fig. 5.

Electron micrographs of pancreas of ADH+ (a) and ADH− (b) deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Presence of apoptotic cell (AP) and swelling of glandular ER (denoted by D) was found only in pancreas of ADH− deer mice. However, disintegration of glandular ER of acini to vesicles (V) and swelling of nuclear envelope (NES) was also seen in ADH+ deer mice (marked by arrows).

Fig. 6.

TUNEL assay using TdT-FragEL™ in situ apoptosis detection kit in paraffin-embedded thin sections of pancreas of ADH+ deer mice (a) and ADH− deer mice (b) fed 3.5% ethanol. Intensely stained apoptotic cells are marked by the arrows.

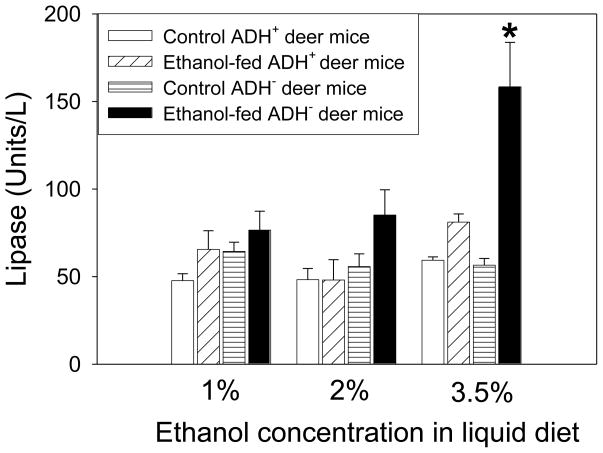

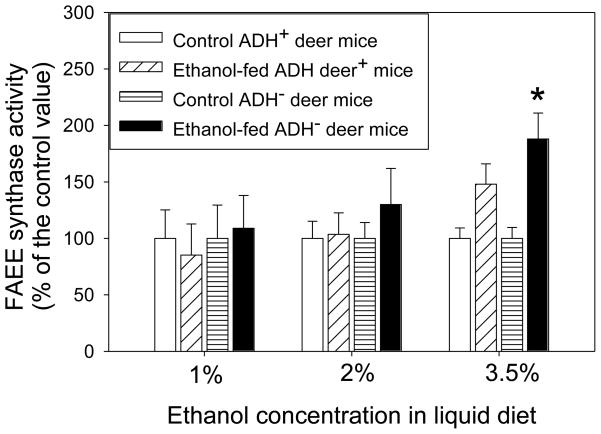

Markers of pancreatic injury and ER stress

Between the two conventional markers of pancreatic injury (lipase and amylase), only the plasma lipase was significantly elevated in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5 % ethanol (Fig. 7). Plasma amylase levels did not show any significant change in all the groups of ethanol-fed animals vs. respective pair-fed controls (data not shown). However, the pancreatic FAEE synthase activity increased 2 folds only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol as compared to respective pair-fed control group (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Lipase activity in the plasma of ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5). *- p value <0.05.

Fig. 8.

Pancreatic FAEE synthase activity in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol for 2 months expressed as percent of the control value. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5). *- p value <0.05.

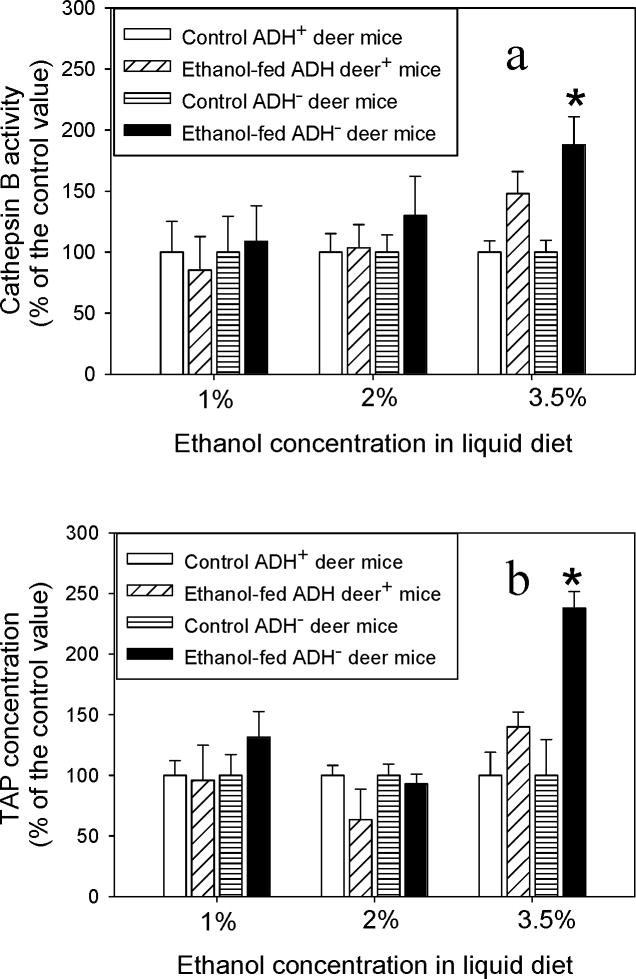

The average values for cathepsin B were ~109, 130 and 188% in ADH− deer mice vs. ~85, 103 and 148% in ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol, respectively, than the respective control values (Fig. 9a). Similarly, average pancreatic TAP values were 130, 93 and 238% in ADH− deer mice and ~96, 66 and 140% in ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 or 3.5% ethanol, respectively, as compared to corresponding controls (Fig. 9b).

Fig. 9.

Pancreatic cathepsin B (a) and TAP (b) in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed 1, 2 and 3.5% ethanol for 2 months expressed as percent of the control value. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5). *- p value <0.05.

As shown by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 10, upper panel) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 10, lower panel), GRP78/Bip (an established marker of ER stress) was significantly over expressed in the pancreas of ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol than that in pair-fed control group. The relative average intensity of GRP78 bands was ~7 fold greater in the pancreas of ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol than its pair-fed controls (Fig. 10a and b, lower panel). However, no significant changes were observed either in ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol or ADH− and ADH+ deer mice fed 1 or 2% ethanol as compared to the corresponding pair-fed controls (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

Immunohistochemical staining of GRP78/BiP (upper panel) in the pancreas of ADH+ (a) and ADH− (b) deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol for 2 months. The brown staining indicates GRP78 expression. Similarly, lower panel shows Western blot analysis of the homogenates of pancreas of pair-fed (lanes 1–3) and ethanol (3.5%)-fed (lanes 4–6) ADH− deer mice for 2 months. Lower panel shows western blot analysis (a) and intensity of bands using densitometry analysis (b). Ten μg proteins were loaded in each well. β-actin was used as loading control. Values are mean ± SEM (n=3). *- p value <0.05.

Discussion

After biliary duct disease, chronic alcohol abuse is the second major cause of pancreatitis (Kaphalia, 2010). Pancreatic steatosis is early stage pathology of alcoholic pancreatitis that develops after long-term ethanol exposure (Wilson et al., 1982; Lopez et al., 1996; Simsek and Singh, 1990). How this early stage steatosis progresses to inflammation stage in alcoholic pancreatitis is not well understood. Our findings after subchronic exposure of ethanol to deer mice suggest that both hepatic ADH deficiency and alcohol concentration in the body are the determining factors for the initiation of ethanol-induced pancreatic injury, which can progress to inflammation and fibrosis stages after chronic exposure.

ADH− deer mice lack hepatic ADH 1 isoform and metabolize ethanol in vivo at rates approximately one half that in ADH+ deer mice despite increases in hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 (cyp 2E1) levels by several folds (Burnett and Felder, 1980; Shigeta et al., 1984). A similar rise of BAC in animals fed 3.5% ethanol could be attributed to increased intake of ethanol vs. the rate of ethanol oxidation and excretion. In fact, BAC may rise as high as ~15 fold greater in ADH 1 knockout mice vs. wild type at 6 hr after an ethanol dose of 3.5 g/kg body weight (Deltour et al., 1999). Contrary to BAC, comparable levels of acetaldehyde (oxidative metabolite of ethanol) in both strains could be attributed to rapid oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetate catalyzed by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase at the rate it is formed (Rognstad and Grunnet, 1979). Despite the hepatic ADH deficiency, some amount of ingested ethanol can also be oxidized by other isozymes of ADH and microsomal cyp 2E1 (Kaphalia and Ansari, 2001). About 10 fold reduced production of acetaldehyde has been reported in the hepatic cytosol of ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice incubated with ethanol (EkstrÖm et al., 1989). However, ours is the first report to compare blood acetaldehyde levels in ADH− and ADH+ deer mice after subchronic ethanol exposure.

Several reports suggest that hepatic cyp 2E1 plays a minor role in ethanol oxidation (Burnett and Felder, 1980; Shigeta et al., 1984; Norsten et al., 1989; Wu et al., 2006). Even increased BAC in ADH+ deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol found in our studies could be attributed to down regulation of hepatic ADH 1 as reported recently in intragastric ethanol infusion mouse model (Ciuclan et al., 2010). Although pancreatitis occurs frequently in patients dying from alcoholic liver disease, different risk factors may confer susceptibility to alcoholic chronic pancreatitis vs. alcoholic liver disease (Nagata et al., 1982; Renner et al., 1984; Nakamura et al., 2004). Extrahepatic organs such as pancreas have been reported to possess no or little oxidative metabolism for ethanol (Laposata and Lange, 1986). Increases in body’s ethanol concentration in our model due to hepatic ADH deficiency may facilitate its greater circulation to extrahepatic organs such as pancreas frequently damaged during chronic alcohol abuse (Laposata and Lange, 1986). However, role of hepatic ADH polymorphism in alcoholic pancreatitis as well as its parallelism with alcoholic liver disease yet to be established (Renner et al., 1984; Hanck et al., 2003).

Fatty pancreas found only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol could be attributed to greater synthesis of neutral lipids such as triacylglycerides and cholesterol esters due to increased transcription of genes regulating the biosynthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol after exposure to ethanol (Wilson et al., 1982; Simsek and Singh, 1990; Lopez et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2006; Bhopale et al., 2006; Kaphalia, 2010). It is likely that etherification of fatty acids and cholesterol acts as compensatory mechanism for the disposition of both, excess circulating ethanol as well as accumulated fatty acids and cholesterol in the pancreas. Ethanol exposure is also known to induce pancreatic fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE) synthase activity, which is abundant in mammalian pancreas (Pfutzer et al., 2002). Such induction can also contribute to the enhanced endogenous synthesis of FAEEs in the pancreas. FAEEs are known pancreatic toxins and cause injury to pancreatic acinar cells (Werner et al., 1997, 2002; Criddle et al., 2004, 2006; Bhopale et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2008; Petersen et al., 2009). Pancreatic injury observed in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol could be attributed to substantial formation of FAEEs (nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol) in the pancreas, since statistically different levels of blood acetaldehyde in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed ethanol were not found in the present study.

Most likely, the synthesis of FAEEs takes place in ER membranes of pancreatic acinar cells; a major site for the synthesis of cellular proteins and lipids as ~5 folds greater levels of FAEEs were found in the microsomal fraction than those in the cytosolic fraction of the pancreatic homogenate incubated with [1-14C] ethanol (unpublished data). Being lipophilic, FAEEs accumulate in lipid-rich membranes of the exocrine pancreas and can impair membrane functions and/or be transported to mitochondria along with fatty acids causing mitochondrial toxicity such as uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (Lange and Sobel, 1983). In fact, FAEEs are known to consistently evoke Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores, increase fragility of lysosomal membrane, activate trypsinogen (zymogen) and cause cell death (Haber et al., 1993; Criddle et al., 2004, 2006; Bhopale et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2008; Petersen et al., 2009). These esters can also activate key regulators of the inflammation and other pro-inflammatory signalling pathways as compared to their inactivation by acetaldehyde (Kaphalia and Ansari, 2001; Gukovskaya et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2008). In our study, ethanol-induced pancreatic toxicity appears to be restricted to exocrine pancreas as enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of FAEEs are mainly localized in the acinar cells of exocrine pancreas. This is evident from the intact islets of Langerhans (endocrine pancreas) in our morphological studies. It is likely that late stage pancreatitis and fibrosis leading to massive structural and functional destruction of the gland may also inflict endocrine pancreas. However, a literature report indicating FAEEs-induced oxidative stress is not available yet to the best of our knowledge.

It takes several years of alcohol abuse to induce chronic pancreatitis in certain number of individuals. Increased endogenous concentration of FAEEs could be responsible for the initiation of pancreatic injury as found in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. Increasing the endogenously formed FAEEs by prolonging the durations of ethanol exposure progresses the disease to inflammation stage and beyond; a hypothesis yet to be tested in our animal model. A small amount of FAEEs formed in some pair-fed controls corresponding to 3.5% ethanol-fed deer mice of both strains could be related to endogenous production of ethanol through fermentation of dextrose by the gut bacteria (Menzey et al., 1975).

Pancreatitis-like injury has been reported in vivo in rats by FAEEs (Werner et al., 1997). A reduced energy out put due to uncoupling effect of FAEEs on oxidative phosphorylation may significantly impair normal functions of ER membranes resulting in ER stress and apoptotic cell death as found in the present study. We have ruled out the role of acetaldehyde in ER stress due to its comparable levels in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed ethanol. As discussed earlier, increased fragility of the lysosomal membrane by FAEEs could release hydrolase (cathepsin B) capable of activating trypsinogen to trypsin; a critical mediator of cell death by necrosis and inflammatory processes (Lankisch and Banks, 1998; Ji et al., 2009). Elevated cytoplasmic cathepsin B as found in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol can also indirectly induce a cascade of inflammatory responses (Fortunato et al., 2006). Thus, trypsin and cathepsin B induced significantly in ADH− vs. ADH+ deer mice fed ethanol could be critical mediators of necrotic cell death (Haber et al., 1993; Halangk et al., 2000; Kukor et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2006). However, pancreatic injury assessed in our model appears to be an early stage. Therefore, prolonging the duration of ethanol exposure in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol (an optimal tolerable dose) could be important for understanding the metabolic basis and mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis.

Increased expression of GRP78 in pancreas only in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol could be associated again with increased endogenous biosynthesis of FAEEs in the exocrine pancreas. Aggregation of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen leads to ER stress in a number of diseases, and can induce unfolded protein response (UPR, a protective mechanism that limits ER stress-induced cell damage). This is an evolutionary conserved mechanism whereby cells respond to stress conditions that target ER membranes (Reddy et al., 2003; Kaplowitz and Ji, 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Kubisch and Logsdon, 2007). Earlier, we have shown that ethanol exposure decreases ATP production and induces apoptosis via activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 in HepG2 cells (Wu et al., 2006). Ethanol itself, even at high concentration, has little effect on the functional performance of isolated pancreatic acinar cells, whereas FAEEs might cause Ca2+-dependent necrosis due to a compromised ATP generation (Criddle et al., 2006; Petersen et al., 2009). Therefore, necrotic cell death in alcoholic pancreatitis could be attributed to a set of multiple toxic events and formation of FAEEs rather than one single event.

The data on substantial formation of endogenous FAEEs, and injury and ER stress in the pancreas of ethanol-fed ADH− deer mice suggest that the key determinants in ethanol-induced pancreatic injury are hepatic ADH-deficiency and high ethanol levels in the body. Our data also suggest that altered lipid homeostasis and increased biosynthesis of FAEEs in the pancreas are closely associated with ER stress and apoptotic cell death observed in ADH− deer mice fed 3.5% ethanol. However, a steady endogenous synthesis of FAEEs and their accumulation during chronic alcohol abuse can attain a concentration toxic to the pancreas. A prolonged ER stress and sustained Ca2+ release from ER membrane can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines and related cytotoxic events resulting into inflammation and necrotic cell death. Therefore, role of endogenously synthesized FAEEs in ethanol-induced ER stress and identification of toxic pathways involved cells death need to be fully elucidated in deer mouse model to unravel the metabolic basis of alcoholic pancreatitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant AA13171 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NIAAA. The authors also acknowledge the assistance of the Research Histopathology Core, Sealy Center for Environmental Health & Medicine, UTMB supported through NIEHS Center grant P30ES06676.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baker H, Luisada-Opper A, Sorrell MF, Thomson AD, Frank O. Inhibition by nicotinic acid of hepatic steatosis and alcohol dehydrogenase in ethanol-treated rats. Exp Mol Pathol. 1973;19:106–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(73)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhopale KK, Wu H, Boor PJ, Popov VL, Ansari GA, Kaphalia BS. Metabolic basis of ethanol-induced hepatic and pancreatic injury in hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase deficient deer mice. Alcohol. 2006;39:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett KG, Felder MR. Ethanol metabolism in Peromyscus genetically deficient in alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner R, Xie J, Bank S. Does acute alcoholic pancreatitis exists with preexisting chronic pancreatitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:201–202. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuclan L, Ehnert S, IIkavets I, et al. TGF-β enhances alcohol dependent hepatocyte damage via down-regulation of alcohol dehydrogenase I. J Hepatol. 2010;52:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criddle DN, Raraty MG, Neoptolemos JP, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH, Sutton R. Ethanol toxicity in pancreatic acinar cells: mediation by nonoxidative fatty acid metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2004;101:10738–10743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403431101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criddle DN, Sutton R, Petersen OH. Role of Ca2+ in pancreatic cell death induced by alcohol metabolites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S14–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltour L, Foglio MH, Duester G. Metabolic deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase Adh1, Adh3, and Adh4 null mutant mice. Overlapping roles of Adh1 and Adh4 in ethanol clearance and metabolism of retinol to retinoic acid. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16796–16801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom G, Cronholm T, Norsten-Hoog C, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Dehydrogenase-dependent metabolism of alcohols in gastric mucosa of deer mice lacking hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:1989–1994. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90008-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norsten C, Cronholm T, Ekstrom G, Handler JA, Thurman RG, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Dehydrogenase-dependent ethanol metabolism in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) lacking cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase. Reversibility and isotope effects in vivo and in subcellular fractions. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5593–5597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato F, Deng X, Gates LK, et al. Pancreatic response to endotoxin after chronic alcohol exposure: switch from apoptosis to necrosis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G232–241. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gukovskaya AS, Mouria M, Gukovsky I, et al. Ethanol metabolism and transcription factor activation in pancreatic acinar cells in rats. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:106–118. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber PS, Wilson JS, Apte MV, Pirola RC. Fatty acid ethyl esters increase rat pancreatic lysosomal fragility. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;121:759–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halangk W, Lerch MM, Brandt-Nedelev B, et al. Role of cathepsin B in intracellular trypsinogen activation and the onset of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:773–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanck C, Schneider A, Whitcomb DC. Genetic polymorphisms in alcoholic pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:613–23. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji B, Gaiser S, Chen X, Ernst SA, Logsdon CD. Intracellular trypsin induces pancreatic acinar cell death but not NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17488–17498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphalia BS. Encyclopedia of Environmental Health. Elsevier; 2010. Pancreatic Toxicology. (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- Kaphalia BS, Ansari GA. Fatty acid ethyl esters and ethanol-induced pancreatitis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2001;47:OL173–179. Online Pub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphalia BS, Ansari GA. Purification and characterization of rat pancreatic fatty acid ethyl ester synthase and its structural and functional relationship to pancreatic cholesterol esterase. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2003;17:338–345. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphalia BS, Cai P, Khan MF, Okorodudu AO, Ansari GA. Fatty acid ethyl esters: markers of alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Alcohol. 2004;34:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaphalia BS, Khan MF, Carroll RM, Aronson J, Ansari GAS. Subchronic toxicity of 2-chloroethanol and 2-bromoethanol in rats. Res Commun Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;1:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz N, Ji C. Unfolding new mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S7–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershengol’ts BM, Alekseev VG, Gavrilova EM, Li NG. Various causes of decreased aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in the rat liver and blood in chronic alcoholic intoxication. Vopr Med Khim. 1985;31:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsten MA, Haber PS, Wilson JS, Lieber CS. The effect of chronic alcohol administration on cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:25–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02825418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisch CH, Logsdon CD. Secretagogues differentially activate endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1804–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00078.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukor Z, Mayerle J, Kruger B, Toth M, Steed PM, Halangk W, et al. Presence of cathepsin B in the human pancreatic secretory pathway and its role in trypsinogen activation during hereditary pancreatitis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21389–21396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange LG, Sobel BE. Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by fatty acid ethyl esters, myocardial metabolites of ethanol. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:724–731. doi: 10.1172/JCI111022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankisch PG, Banks PA. Pancreatitis. New York: Springer-Verlag Berlin; 1998. p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- Laposata EA, Lange LG. Presence of nonoxidative ethanol metabolism in human organs commonly damaged by ethanol abuse. Science. 1986;231:497–499. doi: 10.1126/science.3941913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JM, Bombi JA, Valderrama R, et al. Effects of prolonged ethanol intake and malnutrition on rat pancreas. Gut. 1996;38:285–292. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurements with folin phenol Reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manautou JE, Carlson GP. Ethanol-induced fatty acid ethyl ester formation in vivo and in vitro in rat lung. Toxicology. 1991;70:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(91)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Imbembo AL, Potter JJ, Rent KC, Lombardo RL, Hot PR. Endogenous ethanol production and hepatic disease following jejunoileal bypass for morbid obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:1277–1283. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.11.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Kobayashi Y, Ishikawa A, Maruyama K, Higuchi S. Severe chronic pancreatitis and severe liver cirrhosis have different frequencies and are independent risk factors in male Japanese alcoholics. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:879–887. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norsten C, Cronholm T, Ekstrom G, Handler JA, Thurman RG, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Dehydrogenase-dependent ethanol metabolism in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) lacking cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase. Reversibility and isotope effects in vivo and in subcellular fractions. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5593–5597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutinen H, Lindros KO, Salaspuro M. Determinants of blood acetaldehyde level during ethanol oxidation in chronic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1983;7:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer KR, Jenkins WJ. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in alcoholic subjects. Hepatology. 1985;5:260–263. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandol SJ, Raraty M. Pathobiology of alcoholic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2007;7:105–114. doi: 10.1159/000104235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panes J, Caballeria J, Guitart R, et al. Determinants of ethanol and acetaldehyde metabolism in chronic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panes J, Soler X, Pares A, et al. Influence of liver disease on hepatic alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:708–714. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OH, Tepikin AV, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Sutton R, Criddle DN. Fatty acids, alcohol and fatty acid ethyl esters: Toxic Ca2+ signal generation and pancreatitis. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfutzer RH, Tadic SD, Li HS, et al. Pancreatic cholesterol esterase, ES-10, and fatty acid ethyl ester synthase III gene expression are increased in the pancreas and liver but not in the brain or heart with long-term ethanol feeding in rats. Pancreas. 2002;25:101–106. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RK, Mao C, Baumeister P, Austin RC, Kaufman RJ, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors: role of ATP binding site in suppression of caspase-7 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20915–20924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner IG, Savage WT, Stace NH, Pantoja JL, Schultheis WM, Peters RL. Pancreatitis associated with alcoholic liver disease. A review of 1022 autopsy cases. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:593–599. doi: 10.1007/BF01347290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinderknecht H. Activation of pancreatic zymogens. Normal activation, premature intrapancreatic activation, protective mechanisms against inappropriate activation. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:314–321. doi: 10.1007/BF01318124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognstad R, Grunnet N. Enzymatic pathways of ethanol metabolism. In: Majchrowicz EaNEP., editor. Biochemistry and Pharmacology of Ethanol. New York: Plenum Press; 1979. pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Whitcomb DC, Singer MV. Animal models in alcoholic pancreatitis-What can we learn. Pancreatology. 2002;2:189–203. doi: 10.1159/000058033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkawi M. In vivo inhibition of liver alcohol dehydrogenase by ethanol administration. Life Sci. 1984;35:2353–2357. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigeta Y, Nomura F, Iida S, Leo MA, Felder MR, Lieber CS. Ethanol metabolism in vivo by the microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system in deer mice lacking alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:807–814. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore JD, Theorell H. Substrate inhibition effects in the liver alcohol dehydrogenase reaction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1966;117:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek H, Singh M. Effect of prolonged ethanol intake on pancreatic lipids in the rat pancreas. Pancreas. 1990;5:401–407. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Simsek H. Ethanol and the pancreas. Current status Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1051–1062. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90033-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Halsall S, Peters TJ. Role of hepatic acetaldehyde dehydrogenase in alcoholism: demonstration of persistent reduction of cytosolic activity in abstaining patients. Lancet. 1982;2:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Hu R, Lugea A, et al. Ethanol feeding alters death signaling in the pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;32:351–359. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000220859.93496.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J, Laposata M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, et al. Pancreatic injury in rats induced by fatty acid ethyl ester, a nonoxidative metabolite of alcohol. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:286–294. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J, Saghir M, Warshaw AL, et al. Alcoholic pancreatitis in rats: injury from nonoxidative metabolites of ethanol. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G65–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00419.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JS, Colley PW, Sosula L, Pirola RC, Chapman BA, Somer JB. Alcohol causes a fatty pancreas. A rat model of ethanol-induced pancreatic steatosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1982;6:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1982.tb05389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557–1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Bhopale KK, Ansari GAS, Kaphalia BS. Ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in rat pancreatic acinar AR42J cells: role of fatty acid ethyl esters. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:1–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Cai P, Clemens DL, Jerrells TR, Ansari GA, Kaphalia BS. Metabolic basis of ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in recombinant HepG2 cells: role of nonoxidative metabolism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahlten RN, Jacobson CJ, Neijtek ME. Underestimation of alcohol dehydrogenase as a result of various technical pitfalls of the enzyme assay. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:1973–1976. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Shen X, Wu J, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates cleavage of CREBH to induce a systemic inflammatory response. Cell. 2006;124:587–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]