Abstract

Objective To determine which bedside method of detecting inadvertent endobronchial intubation in adults has the highest sensitivity and specificity.

Design Prospective randomised blinded study.

Setting Department of anaesthesia in tertiary academic hospital.

Participants 160 consecutive patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists category I or II) aged 19-75 scheduled for elective gynaecological or urological surgery.

Interventions Patients were randomly assigned to eight study groups. In four groups, an endotracheal tube was fibreoptically positioned 2.5-4.0 cm above the carina, whereas in the other four groups the tube was positioned in the right mainstem bronchus. The four groups differed in the bedside test used to verify the position of the endotracheal tube. To determine whether the tube was properly positioned in the trachea, in each patient first year residents and experienced anaesthetists were randomly assigned to independently perform bilateral auscultation of the chest (auscultation); observation and palpation of symmetrical chest movements (observation); estimation of the position of the tube by the insertion depth (tube depth); or a combination of all three (all three).

Main outcome measures Correct and incorrect judgments of endotracheal tube position.

Results 160 patients underwent 320 observations by experienced and inexperienced anaesthetists. First year residents missed endobronchial intubation by auscultation in 55% of cases and performed significantly worse than experienced anaesthetists with this bedside test (odds ratio 10.0, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 434). With a sensitivity of 88% (95% confidence interval 75% to 100%) and 100%, respectively, tube depth and the three tests combined were significantly more sensitive for detecting endobronchial intubation than auscultation (65%, 49% to 81%) or observation(43%, 25% to 60%) (P<0.001). The four tested methods had the same specificity for ruling out endobronchial intubation (that is, confirming correct tracheal intubation). The average correct tube insertion depth was 21 cm in women and 23 cm in men. By inserting the tube to these distances, however, the distal tip of the tube was less than 2.5 cm away from the carina (the recommended safety distance, to prevent inadvertent endobronchial intubation with changes in the position of the head in intubated patients) in 20% (24/118) of women and 18% (7/42) of men. Therefore optimal tube insertion depth was considered to be 20 cm in women and 22 cm in men.

Conclusion Less experienced clinicians should rely more on tube insertion depth than on auscultation to detect inadvertent endobronchial intubation. But even experienced physicians will benefit from inserting tubes to 20-21 cm in women and 22-23 cm in men, especially when high ambient noise precludes accurate auscultation (such as in emergency situations or helicopter transport). The highest sensitivity and specificity for ruling out endobronchial intubation, however, is achieved by combining tube depth, auscultation of the lungs, and observation of symmetrical chest movements.

Trial registration NCT01232166.

Introduction

Endotracheal intubation is a routine procedure in anaesthetic, critical care, and emergency practice. The procedure is performed by many clinicians from different specialties with different levels of experience in airway management. Numerous studies have been published comparing different methods of discerning between endotracheal and oesophageal placement of the tube.1 2 3 Serious complications can occur from inadvertent placement of the endotracheal tube in a mainstem bronchus, such as hypoxaemia caused by atelectasis formation in the unventilated lung and hyperinflation and barotrauma with development of a pneumothorax of the intubated lung.4 Furthermore, the American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed Claims Project showed that endobronchial intubation accounts for 2% of adverse respiratory claims in adults and 4% in children.5 6 Proper positioning of the endotracheal tube in relation to the carina is therefore clinically important.

Institutions like the American Heart Association and the European Resuscitation Council7 8 and major textbooks on anaesthetics9 10 recommend bilateral auscultation of the chest to diagnose and prevent endobronchial intubation. Brunel et al, however, found that 60% of endobronchial intubations in patients in intensive care occurred despite equal breath sounds on examination.11 Even continuous auscultation could not detect endobronchial intubation in 79 cases reported in the Australian Incident Monitoring Study.12 Other clinical tests to verify correct positioning have therefore become routine, including observation of symmetrical chest movements, palpation of symmetrical chest expansion, and use of the cm scale printed on the endotracheal tube.4 13

We compared the sensitivity and specificity of different bedside methods of verifying correct placement of the endotracheal tube: bilateral auscultation of the chest; observation and palpation of symmetrical chest movements; use of the cm scale printed on the tube; and a combination of all three methods. We further hypothesised that sensitivity and specificity of these clinical methods would increase as a function of the anaesthetist’s experience.

Methods

The study included 160 patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists category I/II) aged 19-75. All were scheduled for elective gynaecological or urological surgery in an academic tertiary hospital. Patients with pre-existing lung disease, pleural effusion, anticipated difficult airway, or known endobronchial or tracheal lesions or who were at risk for aspiration of gastric contents were excluded.

Anaesthesia was induced with intravenous bolus doses of 2-3 mg/kg propofol, 2 µg/kg fentanyl, and 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium. The trachea was intubated by using direct laryngoscopy with a standard endotracheal tube without a Murphy eye. To prevent endobronchial lesions, women were intubated with a 6.5 mm inner diameter tube, and men were intubated with a 7.5 mm inner diameter tube. The tube cuff pressure was continuously monitored and kept less than 30 cm H2O. To prevent any damage to the lungs, the airway pressure limit valve of the anaesthesia machine was set to 25 cm H2O.

Design

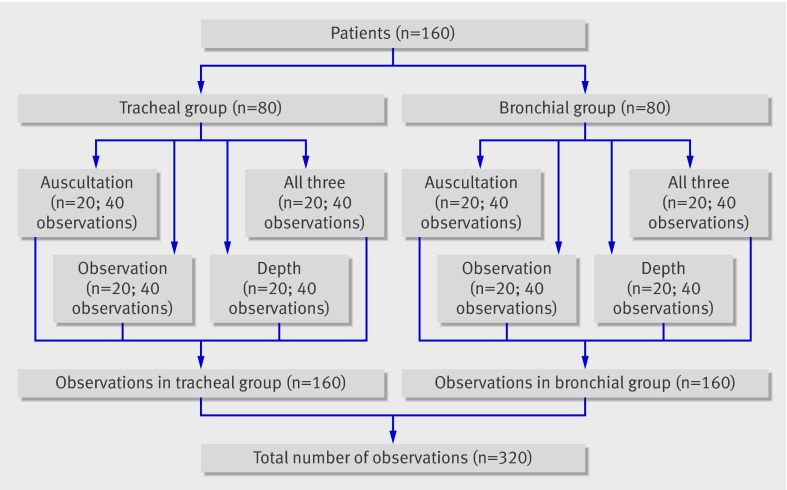

This was a prospective randomised blinded trial. Randomisation was based on computer generated sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes that were opened after induction of anaesthesia. Each envelope contained two instructions: where the endotracheal tube had to be placed in relation to the carina (that is, endobronchially or endotracheally), and which clinical test(s) had to be used by the two study anaesthetists to verify the position of the tube. Accordingly 160 patients were randomly assigned to one of eight groups, each including 20 participants (figure).

Group assignment according to randomisation of 160 patients; an experienced and an inexperienced anaesthetist independently assessed each patient, resulting in 320 observations

Intervention

In four of these eight groups, one of two anaesthetists (CS or SCK) positioned the endotracheal tube 2.5-4 cm above the carina (three to four tracheal rings, the “correct” position) using direct visualisation through a fibreoptic bronchoscope (tracheal group). In the other four study groups the same anaesthetists positioned the tube in the right mainstem bronchus (the “wrong” position), again under direct visualisation through a fibreoptic bronchoscope (bronchial group). To verify the position of the tube, each patient within the tracheal and bronchial groups was assessed by either bilateral auscultation of the lungs only, with the patient’s thorax and head covered with blankets to blind participants to thorax movements and tube insertion depth (auscultation group, n=20); or observation and palpation of symmetrical chest movements without auscultation of the lungs, with the patient’s head covered with blankets to blind participants to tube insertion depth (observation group, n=20); or estimation of tube position by observing the tube cm scale without lung auscultation, with the patient’s thorax covered by blankets to blind participants to thorax movements (tube depth group, n=20); or a combination of all three methods mentioned above (n=20) (figure).

After the tube was bronchoscopically positioned according to the randomised designation, an anaesthetist with at least two years’ experience in anaesthetics and a first year resident in anaesthetics, each blinded to tube position, independently assessed each patient to evaluate the tube position.

During the evaluation process the patients’ lungs were manually ventilated with a maximum peak inspiratory pressure of 25 cm H2O. The anaesthesia machine was covered with blankets to blind study anaesthetists to values on various monitors (such as end tidal CO2 or pressure-volume loops). Study anaesthetists had a maximum of 30 seconds to judge the tube position. After making their judgments, anaesthetists left the operating room without being informed about the real position of the tube to exclude a learning effect; the experienced and inexperienced anaesthetists were not permitted to consult each other. After completion of the evaluation process of the position of the tube in bronchial group, the tube was correctly positioned three to four tracheal rings (2.5-4 cm) above the carina.

The tube was correctly positioned in relation to the carina by using a slight modification of the method described by Evron et al.14 Specifically, the bronchoscope was advanced to the distance of the carina. The insertion depth of the bronchoscope was then marked, the bronchoscope pulled back until the tip of the tube was seen, and the distance from the marker to the aperture of the breathing circuit measured. The number of tracheal rings was counted as the bronchoscope was withdrawn and was always between three and four above the carina. As the tip-carina distance was known precisely by applying this method, no additional chest radiography was done. We used an extra thin bronchoscope (Olympus BF-20) with an outer diameter of only 2 mm to prevent any damage to the bronchial tree.

Thirty two anaesthetists with at least two years’ training in anaesthetics and 22 with less than 12 months’ training participated in the study. A large number of anaesthetists were asked to participate to exclude a learning effect during the study.

Main outcome measures

An independent investigator recorded the correct and incorrect judgments of the tube position and the individual depths of correct and endobronchial tube positions in all patients.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means (SD) or counts and relative frequencies. We used a logistic regression model to compare the frequencies of correct and incorrect identification of tube position between the bedside tests. Incorrect status was the outcome and the predictor was each bedside test as index variable. As each patient was examined by two examiners we allowed for clustering by calculating robust standard errors.

Sensitivities and specificities were calculated as proportions of correct observations. To allow for clustering we used a linear random intercept model with generalised least squares estimates, assuming a Gaussian distribution of the random effects with patients as the cluster variable. We used the Wald test from a linear random effects model, with bedside test as covariate, to assess differences in sensitivities and specificities between bedside tests.

We tested whether experienced examiners differed from inexperienced examiners in their ability to identify a correctly positioned endotracheal tube. Given the design, the examiners can be seen as matched pairs nested within patients. We used an exact McNemar’s method to test the hypothesis of no difference between experienced and inexperienced examiners’ ability and calculated matched odds ratios with exact 95% confidence intervals. We repeated this analysis for each bedside test. The difference in tube insertion depth between women and men was compared with an unpaired t test. A two sided P<0.05 was generally considered significant. For data management and calculations we used MS Excel 11.5 and Stata 9.2 for Mac OS X.

Results

We asked 164 consecutive patients to participate in the study, and 160 category I or II (American Society of Anesthesiologists) patients gave written informed consent and were recruited to the study. There were more women than men (118 v 42), and, as might be expected, men were taller and heavier than the women. The tracheal and bronchial groups assessed by the same clinical method, however, were well balanced for age, weight, and height (table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics split according to position of tube and method of assessment of position of tube. Figures are means (SD)

| Method of assessment* of position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auscultation | Observation | Depth | All three | |

| Bronchial position† | ||||

| Men | 10 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Women | 10 | 10 | 14 | 18 |

| Age (year): | ||||

| Men | 55 (23) | 65 (5) | 61 (5) | 54 (3) |

| Women | 40 (11) | 38 (14) | 42 (16) | 37 (11) |

| Weight (kg): | ||||

| Men | 80 (20) | 88 (16) | 100 (25) | 90 (10) |

| Women | 67 (21) | 68 (15) | 63 (16) | 65 (15) |

| Height (cm): | ||||

| Men | 171 (12) | 175 (8) | 173 (9) | 180 (12) |

| Women | 162 (5) | 163 (7) | 159 (12) | 165 (8) |

| Tracheal position‡ | ||||

| Men | 0 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Women | 20 | 16 | 18 | 12 |

| Age (year): | ||||

| Men | 0 | 58 (8) | 66 (4) | 56 (7) |

| Women | 44 (15) | 45 (15) | 46 (18) | 40 (14) |

| Weight (kg): | ||||

| Men | 0 | 90 (14) | 90 (4) | 104 (24) |

| Women | 70 (14) | 72 (15) | 68 (13) | 66 (15) |

| Height (cm): | ||||

| Men | 0 | 176 (4) | 180 (7) | 183 (9) |

| Women | 167 (5) | 167 (5) | 163 (4) | 169 (6) |

*Bilateral auscultation of chest (auscultation); observation of symmetrical chest movements (observation); checking cm scale (depth); or combination of all three (all three).

†Tube placed in right main stem bronchus.

‡Tube placed 2.5-4 cm above carina..

The results of clinical tests differed significantly in sensitivity for detection of endobronchial intubation (P<0.001). Calculation of odds ratios showed that the depth method and all three methods combined were most useful for correct judgment of the position of the endotracheal tube (table 2). Sensitivity was greatest with the combination of all three clinical tests, but interestingly, tube depth alone was almost as sensitive as the combination of all three clinical tests (88% v 100%; table 3). Tube depth was considerably more sensitive than auscultation of the lungs or observation and palpation of chest movements. In fact, tube depth was most specific in ruling out endobronchial intubation, but this difference did not reach significance (P=0.38). Because of a baseline imbalance, we included sex as a covariate in all regression analyses. Estimates remained virtually unchanged (data not presented).

Table 2.

Summary of 2×2 tables indicating correct and incorrect diagnoses of endobronchial intubation and correct and incorrect diagnoses of excluding endobronchial intubation by different methods for assessment of position of endotracheal tube.* Each of 20 patients in each group assessed independently by experienced and inexperienced anaesthetists resulting in 40 independent observations

| Tube position and diagnosis | Auscultation | Observation | Depth | All three |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endobronchial position: | ||||

| Correct diagnosis | 26 | 17 | 35 | 40 |

| Incorrect diagnosis | 14 | 23 | 5 | 0 |

| Tracheal position: | ||||

| Correct diagnosis | 37 | 36 | 39 | 38 |

| Incorrect diagnosis | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI)† | 10.5 (2.3 to 47.5), P=0.002 | 19.9 (4.5 to 88.5), P<0.001 | 3.2 (0.6 to 17.0), P=0.18 | 1 |

*Bilateral auscultation of chest; observation of symmetrical chest movements; checking cm scale (depth); or combination of all three.

†Odds ratio to predict incorrect tube position according to bedside test with “all three” as baseline category from logistic regression model with 95% confidence intervals calculated from robust standard errors to allow for correlation within patients.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, and 95% confidence intervals of four methods* used to detect or exclude endobronchial intubation estimated with linear random effects models to allow for correlation within patients

| Auscultation | Observation | Depth | All three | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity† (95% CI) | 65 (49 to 81) | 43 (25 to 60) | 88 (75 to 100) | 100‡ |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 93 (84 to 100) | 90 (81 to 100) | 98 (93 to 100.0) | 95 (88 to 100) |

*Bilateral auscultation of chest; observation of symmetrical chest movements; checking cm scale (depth); or combination of all three.

†P<0.001 for difference between methods.

‡Confidence interval not estimable.

Correct evaluation of tube position was a function of anaesthetist’s experience. Experience significantly increased the chance of correct diagnosis (odds ratio 4.6, 95% confidence interval 1.7 to 15.5; P<0.001). The discordance between experienced and inexperienced anaesthetists was mostly explained by auscultation (10.0, 1.4 to 434) and, to some extent, by observation (4.5, 0.9 to 42.8) but not by depth (1.0, 0.1 to 13.8) (table 4).

Table 4.

Influence of anaesthetist’s experience* on detecting or excluding endobronchial intubation by four methods† (n=20 in each group)

| Tube position and diagnosis | Auscultation | Observation | Depth | All three |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endobronchial position: | ||||

| First year correct/incorrect | 9/11 | 7/13 | 17/3 | 20/0 |

| Experienced correct/incorrect | 17/3 | 10/10 | 18/2 | 20/0 |

| Tracheal position: | ||||

| First year correct/incorrect | 18/2 | 16/4 | 20/0 | 18/2 |

| Experienced correct/incorrect | 19/1 | 20/0 | 19/1 | 20/0 |

| Odds ratio‡ (95% CI) | 10.0 (1.4 to 434), P=0.01 | 4.5 (0.9 to 42.8), P=0.065 | 1.0 (0.1 to 13.8), P=0.99 | P=0.5§ |

*Experienced=anaesthetists with at least 2 years of training in anaesthetics; first year=residents with maximum of 1 year of training in anaesthetics.

†Bilateral auscultation of chest; observation of symmetrical chest movements; checking cm scale (depth); or combination of all three.

‡Matched odds ratio for correct diagnosis of experienced v inexperienced anaesthetists with 95% confidence interval and exact McNemar’s significance probability.

§Odds ratio and 95% CI not estimable.

In the bronchial group, by design, the depth of the tip of the endotracheal tube was deeper than in the tracheal group. The final correct position was deeper in men than in women (table 5). With the usual recommended insertion depth of 21 cm in women and 23 cm in men, the distal tip of the tube was less than 2.5 cm away from the carina (the recommended safety distance, to prevent inadvertent endobronchial intubation with changes in the position of the head in intubated patients) in 20% (24/118) of women and 18% (7/42) of men. The shortest correct intubation depth we observed was 19 cm in 10 women with an average height of 157 cm and a BMI of 28.4. An insertion depth of 20 cm in women and 22 cm in men would thus have provided correct positioning in all our patients.

Table 5.

Mean (SD) correct insertion depth (cm) and insertion depth during endobronchial intubation of endotracheal tube measured at incisors in women and men

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Tube in correct tracheal position* | 21.3 (1.2) | 22.7 (1.3)† |

| Tube in incorrect bronchial position‡ | 25.6 (1.7) | 27.1 (2.1)† |

*Insertion depth measured in 160 patients after correct placement of tube 2.5-4 cm above carina.

†P<0.05 compared with women.

‡Insertion depth measured in 80 patients after placement of tube in right mainstem bronchus.

Discussion

Practical implications particularly for clinicians with less experience in airway management

Among single tests, the best way of excluding inadvertent endobronchial intubation with the highest sensitivity is by observing the cm scale printed on each endotracheal tube. Sensitivity of this simple clinical test exceeds auscultation of the lungs by 23%. Furthermore, tube depth seems to be almost independent of the user’s experience and can be used by clinicians even at the beginning of their training with a high sensitivity and specificity. When all three bedside tests were combined—namely, bilateral auscultation of the lungs, observation and palpation of symmetrical chest movements, and referencing the endotracheal tube cm scale—sensitivity was higher than observing the cm scale alone.

Anaesthetists in their first year of training correctly diagnosed endobronchial intubation by auscultation in less than half of the cases. This result is consistent with the findings of Brunel et al, who found that 60% of endobronchial intubations confirmed by chest radiography in patients in an intensive care unit occurred despite equal breath sounds on examination.11 The observed poor detection rate suggests that patients intubated by less experienced clinicians are at risk for endobronchial related complications including atelectasis formation or barotrauma caused by over- inflation of the intubated lung.

Alternative methods for detection of inadvertent endobronchial intubation:

To improve the accuracy of tube placement, various techniques such as ultrasonography of the lungs,15 acoustic reflectometry,16 and computerised analysis of breath sounds via an electronic stethoscope17 have been proposed. Such methods, however, have limited availability and require specialised knowledge for proper use. Another method to prevent endobronchial intubation is to advance the tube to a mark placed on some tubes immediately proximal to the cuff, thereby indicating the correct positioning. The limitation of this method, however, is that this mark is not visible or is poorly visible in patients in whom the view to the vocal cords is limited (that is, those with Cormack-Lehane score III and IV); such patients comprise 6% of those intubated in the operating room and 19% of those intubated before hospital admission.18

Comparison with the 21/23 cm rule

A commonly used and cited method to estimate the correct depth of the endotracheal tube is the 21/23 cm rule—that is, a correct depth of near 21 cm for women and 23 cm for men.4 13 In our study population, no single patient would have been intubated endobronchially had we followed the 21/23 cm rule. To prevent inadvertent endobronchial intubation with changes in the position of the head in intubated patients a safety distance of 2.5 cm from the distal end of the tube to the carina is recommended. Inserting tubes according to the 21/23 cm rule would have resulted in a shorter distance than recommended in 24 of 118 women (20%) and seven of 42 men (18%) of our study population. Changing the 21/23 rule to a 20/22 rule, meaning an insertion depth of 20 cm for adult women and 22 cm for adult men, would have meant the recommended safety margin was not achieved in only 10 of 118 (9%) women and in none of the men. The shortest correct intubation depth we observed was 19 cm in 10 women with an average height of 157 cm and a BMI of 28.4. Therefore, a general 20/22 cm rule, with the possible exception of using 19 cm for smaller women with a higher BMI, might be a safer approach. Clinicians should accept tube depths that differ much from 20 cm in women and 22 cm in men only with extreme caution.

Our findings are consistent with the work by Evron et al, who used a topographic landmark protocol to estimate the correct tube depth and compared this technique with the traditional 21/23 cm rule.14 In their protocol, insertion depth was determined by adding the distance measured from the right corner of the mouth to the right mandibular angle to the distance measured from the right mandibular angle to a point situated on the centre of a line running transversally through the middle of the sternal manubrium. The authors showed that the 21/23 cm rule resulted in a low incidence of endobronchial intubations (5%), but tube repositioning was necessary in 59% of patients compared with only 24% in those patients in whom their landmark protocol was used. The reported high repositioning rate was probably because the authors used a desired tip-carina distance of 4 cm whereas in our study we targeted 2.5 cm.

Relevance of this study in emergency situations

This study was performed in the controlled environment of elective surgery in American Society of Anesthesiologists category I or II patients without respiratory pathology. Even in this controlled situation, first year residents failed to diagnose endobronchial intubation by auscultation in 55% and experienced anaesthetists failed in 15%. In the less controlled setting of emergency intubation in the emergency room or on a ward during resuscitation, with patients often having underlying respiratory pathology, asymmetrical breath sounds might result from underlying pathology. Diagnosis of endobronchial intubation could therefore be impossible by auscultation or observation of symmetrical chest expansion. Additionally, there might be other pressing clinical concerns (such as shock, ongoing bleeding) that make serious auscultation even more difficult, especially for less experienced practitioners.

The sensitivity of auscultation will presumably be even lower in less controlled and noisier circumstances, such as commonly encountered during emergency intubation before admission. Indeed, Schwartz et al showed that the incidence of bronchial intubation by physicians is as high as 15.5% in prehospital emergency care settings and that women are at greater risk than men.19 Under some prehospital circumstances, such as helicopter transport, ambient noise makes auscultation of the lungs essentially impossible. Under such difficult conditions the 20/22 cm rule would be especially helpful.

We note that the 20/22 cm rule does not preclude oesophageal intubation. End tidal CO2 should thus always be measured to confirm that the tube is in the trachea, and CO2 monitoring is recommended by various national and international societies.7 20 Furthermore, the 20/22 cm rule does not obviate the need for auscultation, which remains important for detection of pathological breath sounds including rales and wheezing, especially in intubated patients.

The morphometric characteristics of our study patients were typical for a Western population. The 20/22 cm rule might require modification for populations that are substantially larger or smaller.

Limitations of study

A possible weakness of this study is the relatively small number of patients within each of the eight groups, though to our knowledge our study had the largest number of observations regarding endobronchial intubation. A further limitation is the difference in the number of women and men included in the study (74% v 26%). The incidence of inadvertent endobronchial intubation is higher in women than in men. The study of Brunel et al in intensive care units documented that 70% of endobronchial intubations that were missed by clinical examination occurred in women.11 This finding was confirmed more recently by the Thai Anesthesia Incident Monitoring Study, in which 72% of inadvertent endobronchial intubations occurred in women and only 28% in men.21 Schwartz et al also showed that women are at greater risk for endobronchial intubation after emergency intubations.19 The problem of inadvertent endobronchial intubation is therefore more relevant to women and we therefore considered the imbalance towards more women acceptable.

Conclusions

We conclude that auscultation alone is inadequate for assessment of the depth of endotracheal tube insertion and that checking for symmetrical chest movements is of little use. The hierarchy of the methods used to assess the correct insertion depth should be changed and clinicians should rely more on depth insertion than on auscultation. Even experienced physicians will benefit from using a 20/22 cm rule, and the rule would be especially helpful for physicians with less experience in airway management and in situations where auscultation is difficult or impossible. Clinicians should accept tube insertion depths that differ much from 20 cm in women and 22 cm in men only with extreme caution.

What is already known on this topic

Endotracheal intubation is a routine procedure performed by various clinicians with different levels of experience

Serious complications can result from misplacement of an endotracheal tube in a mainstem bronchus

Bilateral auscultation of the lungs is the recommended method for assessing tube position

What this study adds

When using auscultation, clinicians with limited experience missed endobronchial intubation in 55% of cases, and even experienced clinicians were often unable to detect it

When proper position was estimated on the basis of the tube insertion depth, sensitivity was 85% in first year residents and 90% in experienced anaesthetists

Optimal insertion depth was 20 cm in women and 22 cm in men, and clinicians should be concerned if the depth varies much from this

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributors: CS, PK, and SCK contributed to the design of the trial. CS, PK, SCK, and DIS contributed to the interpretation of the results and writing of the manuscript. AL, AS, CG, SCK, CW, and CS contributed to the recruitment of patients, data collection, and management of the trial. CS, DIS, and HH contributed to the statistical analysis. CS is the guarantor.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna and written informed consent was obtained by independent investigators.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c5943

References

- 1.Knapp S, Kofler J, Stoiser B, Thalhammer F, Burgmann H, Posch M, et al. The assessment of four different methods to verify tracheal tube placement in the critical care setting. Anesth Analg 1999;88:766-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grmec S. Comparison of three different methods to confirm tracheal tube placement in emergency intubation. Intensive Care Med 2002;28:701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael DT, Benbassat M, Arnaudov D, Bohorquez A, Nasseri B. Validation study of two-microphone acoustic reflectometry for determination of breathing tube placement in 200 adult patients. Anesthesiology 2002;97:1371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen RL, Cheney FW. Endobronchial intubation, a preventable complication. Anesthesiology 1987;67:255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morray J, Geiduschek J, Caplan R, Gild W, Cheney F. A comparison of pediatric and adult closed malpractice claims. Anesthesiology 1993;78:461-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplan R, Posner K, Ward R, Cheney F. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 1990;72:828-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolan JP, Deakin CD, Soar J, Böttinger BW, Smith G. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005: section 4. Adult advanced life support; airway management. Resuscitation 2005;67:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emergency Cardiac Care Committee and Subcommittees, American Heart Association. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care. JAMA 1992;268:2171-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone D. Airway management. In: Miller R, ed. Anesthesia. 5th ed. Churchill Livingstone, 2000:1431-2.

- 10.Larsen R. Vorgehen bei orotrachealer Intubation. Larsen Anästhesie. Richard Larsen, 1999:463.

- 11.Brunel W, Coleman DL, Schwartz DE, Peper E, Cohen NH. Assessment of routine chest roentgenograms and the physical examination to confirm endotracheal tube position. Chest 1989;96:1043-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klepper ID, Webb RK, Van der Walt JH, Ludbrook GL, Cockings J. The Australian Incident Monitoring Study. The stethoscope: applications and limitations—an analysis of 2000 incident reports. Anaesth Intensive Care 1993;21:575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts JR, Spadafora M, Cone DC. Proper depth placement of oral endotracheal tubes in adults prior to radiographic confirmation. Acad Emerg Med 1995;2:20-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evron S, Weisenberg M, Harow E, Khazin V, Szmuk P, Gavish D, et al. Proper insertion depth of endotracheal tubes in adults by topographic landmarks measurements. J Clin Anesth 2007;19:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun R, Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Sargasyn AE, Melton S, Hamilton DR, et al. Where’s the tube? Evaluation of hand-held ultrasound in confirming endotracheal tube placement. Prehosp Disaster Med 2004;19:366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raphael DT, Lee H. Acoustic reflectometry detection of an endobronchial intubation in a patient with equal breath sounds. J Clin Anesth 2003;15:41-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor CJ, Mansy H, Balk RA, Tuman KJ, Sandler RH. Identification of endotracheal tube malpositions using computerized analysis of breath sounds via electronic stethoscopes. Anesth Analg 2005;101:735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmermann A, Eich C, Russo SG, Natge U, Bräuer A, Rosenblatt WH, et al. Prehospital airway management: a prospective evaluation of anaesthesia trained emergency physicians. Resuscitation 2006;70:179-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz DE, Lieberman JA, Cohen NH. Women are at greater risk than men for malpositioning of the endotracheal tube after emergent intubation. Crit Care Med 1994;22:1127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donald MJ, Paterson B. End tidal carbon dioxide monitoring in prehospital and retrieval medicine: a review. Emerg Med J 2006;23:728-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sintavanuruk K, Rodanant O, Kositanurit I, Akavipat P, Pulnitiporn A, Sriraj W. The Thai Anesthesia Incident Monitoring Study (Thai AIMS) of endobronchial intubation: an analysis of 1996 incident reports. J Med Assoc Thai 2008;91:1854-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]