Abstract

Background

There is current debate on the appropriate type and extent of medical testing for amateur and hobby athletes before they engage in sports. In particular, views diverge on the value of an ECG at rest.

Methods

We selectively searched the Medline and Embase databases for relevant publications that appeared from 1990 to 2008. The most pertinent ones are discussed here along with current reviews and guidelines that give recommendations on pre-participation testing for amateur athletes.

Results

History-taking and physical examination are standard around the world. The American guidelines on pre-participation examination do not recommend an ECG at rest, yet the guidelines for most European countries explicitly recommend it. No prospective cohort studies have been performed to date that might provide high-grade evidence (class and level) to support this practice. We discuss the pros and cons of an ECG at rest and also present the guideline recommendations on exercise-ECG testing for amateur athletes over age 40.

Conclusion

In accordance with the current European recommendations, and in consideration of the risks of athletic activity, we recommend that all persons participating in sports should undergo a pre-participation examination that includes an ECG at rest. Although primary-prevention campaigns advise physically inactive persons to get regular exercise, prospective studies are still lacking as a basis for recommendations in this group.

The pre-participation examination in sports medicine enables the physician to identify clinically latent or already present diseases that could pose a danger to health if the patient were to engage in intense physical activity. In rare cases, life-threatening conditions can occur, followed by death or resuscitation. The goal of the pre-participation examination is to make athletic activity as safe as possible by minimizing the associated risks to health. This also includes disease prevention.

An Internet-based poll of endurance athletes revealed that only 85% of sports medicine consultations included a physical examination and only 67% included an ECG at rest (1). In the current literature, there is a lack of agreement on the proper content and extent of the pre-participation examination for either leisure-time or high-performance athletes (2– 5, e1– e4). In this article, we present general medical and cardiological aspects of the pre-participation examination.

Methods

A selective search of relevant literature published from 1990 to 2008 was performed in the Medline and Embase databases, on the basis of the following search terms:

pre-participation examination

leisure-time sports

cardiac risk

sudden death during sporting activity

ECG

stress ECG.

An extensive list of references can be found at www.dgsp.de. For the present article, we also made use of review articles, books (13, e6), guidelines, and recommendations (5, 6, 22, e1– e7).

Risks from exercise and sports

The risk of cardiovascular complications during sporting activities is higher in persons who are just beginning to participate in sports or are starting again after an interval of inactivity, as well as in persons over age 35 with latent diseases (6– 9, 10, 13, e8– e12). The risk of a cardiac event during intense sporting activity is 15% to 50% higher in the first few hours of the activity, especially in restarters (e6, e13– e18). The number of expected deaths per 100 000 persons engaging in sports per year lies in the range of 0.5 to 1; in Italy, the corresponding figure is 2.1 deaths per 100 000 persons who are active in sports and 0.8 deaths per 100 000 persons of comparable age who are not active in sports (6, 8, e4, e19– e22). The overall death rate in the normal population over age 35 is 1 to 2 deaths per 1000 persons per year (6, 7, 19). An American case registry documents an increasing number of deaths in recent years, most commonly in (American) football, basketball, and soccer, with marathon running in 14th place (8). These increasing numbers in the American registry are due to improved documentation, greater awareness among physicians, and better reporting (8).

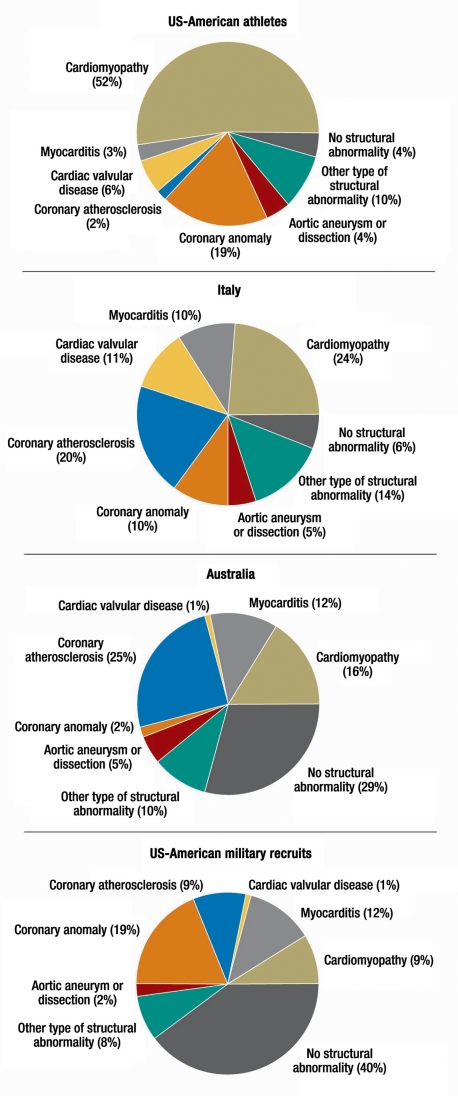

The causes and frequency of cardiovascular complications vary from one cohort study to another (figure 1) (e8– e10, e22). Hypertrophic (obstructive) cardiomyopathy (abbreviated HCM or HOCM) is common in the USA because of its high prevalence among Afro-American athletes; it is much rarer among Caucasian athletes, and in Europe (11). In a study carried out in Italy, arrhythmogenic right-ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) (9, 10, e22) was found to be a common cause. In other studies, the most common finding was a structurally normal heart (6, e8– e10, e22) (figure 1). A post-mortem genetic study („molecular autopsy“) is now recommended in cases of unexplained death during sporting activity (9, 10).

Figure 1.

Among persons over age 35 or 40 (depending on the study; e23), coronary heart disease is the most common cause of cardiac events during sporting activity (6, 8, 19, e6, e22, e24). All over the world, similar recommendations have been issued for further evaluation in this age group (2– 5, 23, e1– e5).

The pre-participation examination in sports medicine

Recommendations regarding the pre-participation examination are based on scientific evidence insofar as relevant studies are available (19, 13, 23, e4, e5, e14, e24– e25). The target groups for evaluation are new participants and restarters in amateur athletics and ambitious leisure-time sports, regardless of age. An Italian retrospective study involving more than 34 000 subjects revealed sports-associated deaths to be less common in persons who had undergone pre-participation examinations by qualified sports physicians (e3). As no large-scale, prospective cohort studies have been performed, there remains disagreement about recommendations in the areas of general medicine and cardiology. There is a consensus, however, that the pre-participation examination in sports medicine should include the following (evidence level C) (4, 5, 12, 13, 19, e1– e7, e26– e29):

a general medical history and sports-related history, with a standardized questionnaire followed by supplementary questioning by a physician;

a physical examination;

an ECG at rest performed and interpreted by qualified personnel.

History

A number of different historical questionnaires have been developed for persons participating in sports (12). A simple and popular one is the Canadian PAR-Q (12, e13, e15) (http://uwfitness.uwaterloo.ca/PDF/ par-q.pdf). The prospective athlete answers seven easy questions; if any are answered in the affirmative, a medical examination is definitely recommended. This questionnaire is meant as a guide only, yet it is adequately validated, specific, and reliable, especially for persons over age 35 (e13, e15). It is administered to nearly all persons applying to run in city marathons in Germany. These persons are thereby alerted to the health risks, and they are advised to get a medical examination if they answer any question „Yes.“

Other, more extensive sports history questionnaires have been published (12). The one used in the German-speaking countries is based on a consensus recommendation derived from many years of clinical experience in sports medicine (12). Most of this three-page questionnaire can be filled out by the prospective athlete him- or herself; only a few questions require additional questioning by a physician. No large-scale prospective studies have been published regarding the use of historical and clinical data to reduce the risk of cardiac events. The current evidence suggests that the ECG at rest is a much more sensitive test than the history and physical examination (5, 19, 23, 24, e19, e24– e28).

Family history is particularly important (13, 14). If there is any history of premature death in a near relative, or of a known, hereditary disease such as Brugada syndrome or cardiomyopathy, a detailed cardiological examination is needed. Persons complaining of syncope, palpitations, dizziness of unknown cause, chest pain, or unusual exertional dyspnea should also undergo further diagnostic assessment. Anyone over age 45 who participates in sports should be tested for coronary heart disease, particularly if one or more risk factors are present (12– 14, e24). Current and previous sporting activities should always be asked about so that potential risks can be assessed at the start of training.

Physical examination

The pre-participation examination should always include a physical examination with blood pressure measurement (1). The physician should look for malformations, skin changes (e.g., acne as a sign of anabolic steroid abuse), and anomalies and variations such as those of Marfan syndrome (e24), which are more commonly seen in tall athletes (basketball players, volleyball players, rowers) (2, 12, 13, e1, e2). Meticulous auscultation of the heart in the supine and sitting positions, and with a Valsalva maneuver, enables the physician to detect the position- or loading-dependent bruits of mitral valve prolapse and HCM. Pulsus bisferiens (biphasic pulse) arouses suspicion of HOCM, while fixed splitting of the second heart sound indicates an atrial septal defect (ASD).

ECG at rest

There is disagreement about the importance of an ECG at rest as a component of the pre-participation examination (evidence level IIa/C) (3, 5, 14, e35). It is required in nine European countries and recommended in six (5). In Germany, an ECG at rest is recommended for persons aged 12 years or older who are beginning to participate in sports. For persons aged 35 or older, an ECG at rest is recommended once every two years, if there are any corresponding symptoms, as part of the statutory medical insurance check-up (”Check-up 35”) and the preventive examination in occupational medicine.

In the USA, an ECG at rest is not routinely included in the pre-participation examination for persons about to undertake sporting activities (15). The current guidelines of the American Heart Association (AHA) (3, e2, e4– e5, e35) recommend one only for persons aged 40 or older (3). A number of studies have addressed the validity of an ECG at rest for persons participating in sports. Of 158 persons who died suddenly during sporting activities, 134 were found to have had heart disease; the sports-medicine check-up without an ECG at rest had aroused suspicion of cardiovascular disease in only 3% of cases (e10, e21). Two prospective, small-scale studies of school children revealed abnormal findings in 0.2% and 2% (e15, e16), while a much larger Italian study revealed abnormal findings in 11.8%, of which 4.8% (e23) were pathological and led to exclusion from sports. According to the Italian data, which covered a 25-year period, 95% of persons with HOCM had pathological findings (23).

Physicians without extensive experience in the interpretation of ECG’s may have difficulty interpreting an athlete’s ECG at rest. This requires special cardiological knowledge relating to sports, in particular with respect to hypertrophic, dilated, and arrhythmogenic right and left ventricular cardiomyopathies (ARVD, ALVD), as well as ion channel disorders such as the long and short QT syndromes (LQTS and SQTS) and Brugada syndrome (11, 17– 19, 21, 24, e25). The recommendations of Corrado et al. (4, 6, 12, e1) are considered standard for the interpretation of an athlete’s ECG. Minor differences between the American and European criteria for pathological findings in the ”sports ECG” concern the QT duration, Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, ventricular extrasystoles, and transient ventricular tachycardias (4).

While history-taking and a physical examination are universally recommended as basic elements of the pre-participation check-up, the role of an ECG at rest for prospective athletes is still a matter of debate.

The ECG at rest: pro and con

Arguments against performing an ECG at rest

Normal variant findings in the ECG at rest are common in high-performance athletes and less common in leisure-time athletes. Negative T waves are common, and not pathological, up to age 16 and in Afro-American athletes (6, e6, e19, e25, e28, e29).

Misinterpretation and false-positive findings are not uncommon, even in expert hands (15).

Physicians interpreting the ECG who do not have special expertise in sports cardiology can miss the diagnosis of newly appreciated entities such as ion channel diseases or cardiomyopathies (box 1).

Some heart diseases are not accompanied by any typical ECG changes (Marfan syndrome, coronary heart disease).

The sensitivity and cost-effectiveness of the ECG at rest are low (15, e19, e24, e25, e38), and false-positive findings entail considerable further costs (e23, e25, e38).

Box 1. Typical abnormal findings on rest ECG: evaluation and interpretation depending on history and physical findings.

Signs of left ventricular hypertrophy without endurance training

AV block without endurance training

Q waves arousing suspicion of prior ischemic event(s) (coronary heart disease?)

Repolarization abnormalities with or without deep negative T waves

Transient ST segment elevation

Prolonged or shortened QT interval

Pre-excitation (delta wave)

Repolarization abnormalities: epsilon wave

(atypical) Right bundle branch block arousing suspicion of Brugada syndrome (physical findings!)

Left bundle branch block (permanent or intermittent)

Atrial fibrillation (intermittent, persistent or permanent, in some cases at night or associated with bradycardia)

Arguments in favor of performing an ECG at rest

An ECG at rest is relatively inexpensive and can be obtained in many physicians’ practices (including those of sports physicians).

Typical pathological findings, such as deep negative T waves, are common, particularly in HOCM (82%); other diseases can also manifest themselves with negative T waves or other changes, such as epsilon waves (high sensitivity) (4, e1).

Left bundle branch block and certain types of right bundle branch block indicate the presence of structural heart disease (4) (box 2).

The current diagnostic criteria (4, 12, 13) standardize and simplify the interpretation of ECGs and improve diagnostic accuracy (4, e1– e3).

False-positive findings are less common in younger athletes and less well trained individuals than in high-performance athletes.

Abnormal ECG findings “disqualify” some 2% of prospective athletes from high-performance sports but can also save lives (4, 5, 16– 19, e5, e25).

If heart disease is diagnosed, it might be possible (depending on the specific diagnosis) to protect the patient’s relatives from adverse cardiac events through further testing (e.g., echocardiography) (4, 13, 14, e2, e4, e19, e23, e24, e30).

An Italian population-based study found an association between the performance of ECGs at rest and a marked decline in sudden deaths (e3): in 25 years of observation, the rate of sudden death dropped from 3.5 to 0.6 per 100 000 person years.

Box 2. Causes of cardiac events among athletes.

-

Cardiomyopathy

hypertrophic

with/without outflow obstruction

dilated, “non-compaction”

arrhythmogenic, right or left ventricular (ARVD, ALVD)

-

Ion channel diseases:

long or short QT syndrome (LQTS, SQTS)

Brugada syndrome

pre-excitation syndrome (with intermittent atrial fluctuation)

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT)

early repolarization

Coronary anomalies, aortic aneurysm or dissection, myocarditis

Cardiac valvular disease, Marfan syndrome

-

Coronary heart disease:

particularly in athletes over age 35

when more than one risk factor is present

in the presence of arterial hypertension (severe)

Consideration of the argument for ECG at rest

The expertise of persons performing sports-medicine evaluations varies from country to country: in the USA, some sports-medicine evaluations are performed by non-physicians, while sports physicians in Italy undergo at least four years of specialized training, including sports cardiology. This type of training is now a desired objective across Europe. No data are available on the cost-effectiveness or sensitivity of sports-medicine evaluations in top athletes in Germany. Preliminary cost-effectiveness calculations for pre-participation sports-medicine evaluations have yielded values between 8000 and 30 000 US dollars per life saved and per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). By current American criteria, these figures imply that such evaluations are worthwhile as a means of saving lives and are, at least, justifiable as a means of improving the quality of life (13, e19).

There are also sound medicolegal and ethical reasons for ECG screening, which have led the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and most European countries to require it (e31, e32).

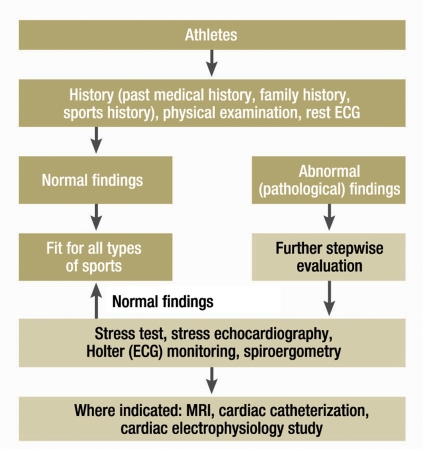

A 12-channel ECG at rest is, therefore, included in the current recommendations of the European countries and the IOC (consensus recommendation) (4, 12, 13, e4, e31, e32). A still unsettled issue is whether an ECG should be performed in childhood or just before the individual begins participating in sports, as ion channel diseases can already pose a danger to health at an early age (24, e7, e15, e16, e19, e22). When the ECG at rest reveals an abnormality, further evaluation should be performed as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

All abnormal findings in the patient’s history, physical examination, or ECG at rest require further general medical and cardiological investigation (figure 2). This investigation can include, for example, transthoracic echocardiography, stress ECG or Holter (ECG) monitoring, or pulmonary function testing, and it should be performed even when the patient has typical exercise-related complaints such as dyspnea, exercise-induced asthma, chest pain, or palpitations—all the more so if the patient has sustained one or more syncopal events. Laboratory tests should be performed as well (12). The proper interpretation of an athlete’s ECG requires specific expertise; in case of doubt, a sports physician with knowledge of the relevant cardiology should be consulted (cf. www.dgsp.de [in German]).

An ECG at rest is not a reliable means of diagnosing coronary heart disease, a condition that may be present, but clinically silent, in older athletes. Such persons should, therefore, undergo a stress ECG (6, 15, 20, e14, e33, e34).

Stress ECG

A stress ECG aids in the recognition of coronary ischemia, arrhythmia, and blood-pressure changes on exertion (16, 18– 20, e15, e33, e34). Ergometric data are not only of diagnostic use, but also serve as the basis for training recommendations (16, e33).

A stress ECG is not a standard element of routine pre-participation testing (18, 19). According to the guidelines, it is indicated only in older persons (men over 45, women over 55) who are about to undertake intensive physical training (Boxes 1 and 3) (16, 18, e15, e33, e34). In this age group, the positive predictive value of a stress ECG is approximately 85%, with pre-test probability 21% and specificity 77% (± 17%). The evidence underlying the guidelines’ recommendations is of level IIb (16, e33, e34).

Box 3. Evidence of possibly pathological ECG changes in persons engaging in sports (from e1, 16).

-

P wave:

Left atrial enlargement: negative portion of P wave in lead V1 >0.1 mV deep and >0.04 s long

Right atrial load: enlarged P waves in leads II and III, or amplitude in V1 >0.25 mV

-

QRS complex:

Vector in the frontal plane: right axis deviation (> +120°) or left axis deviation – 30 to – 90°

Increased voltage: R or S amplitude in the limb leads >2 mV, S in V1 or V 2 >3 mV, or R in V5 or V6 >3 mV (see also Sokolow-Lyon Index)

-

Abnormal Q wave:

Duration longer than 0.04 s or >25% of the height of the following R-wave or QS waves in two or more leads

Right or left bundle branch block with QRS duration >0.12 s

R or R’ wave in lead V1 >0.5mV and R/S ratio >1

-

ST segment, T wave, QT duration:

ST depression or T-wave flattening or inversion in 2 or more leads

Prolongation of the frequency-corrected QT duration beyond 0.44 s (men) or 0.46 s (women)

-

Arrythmias and conduction abnormalities:

Complex ventricular arrhythmias (salvoes, couplets, ventricular tachycardias are considered abnormal)

Frequent ventricular extrasystoles (> 30/hour or > 1000/24 hours) are considered to lie in a “gray zone” between normal and abnormal

Supraventricular tachycardias, atrial flutter or fibrillation

Shortened PQ interval (AV time) (<0.12) with or without delta wave

Sinus bradycardia with heart rate below 40/min at rest (although this can be a normal finding in high-performance athletes)

1st*1, 2nd, or 3rd-degree AV-Block (this can also be a normal finding in high-performance athletes)

1* No shortening on hyperventilation or brief exercise

Comments:

“Atypical” right bundle branch block: evaluation for Brugada syndrome or ARVD

Prolonged QT duration: evaluation for a congenital or acquired long QT syndrome

Shortened QT duration can also be abnormal (so-called short QT syndrome), but note: trained athletes can also have a prolonged QT duration

Slow („slurred“) initial QRS upstroke (delta wave): evaluate for WPW syndrome. Note: in WPW syndrome, Q waves must be absent in I, aVL, and V6, as septal activation is missing.

For asymptomatic persons who have no risk factors and are under age 55, the guidelines give an optional recommendation for a stress ECG (16, 18, 19) (box 4). Stress ECG testing is recommended for persons over age 45 who have more than one risk factor and are about to undergo intensive physical training (evidence level IIb, guidelines of the AHA, ACC and DGK [12, 16, 18]). A stress ECG is mandatory, however, for persons of any age who have cardiac symptoms, and for persons over age 65 with or without symptoms (12– 19, e33, e34). A stress ECG is not indicated if the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) is less than 0.6 but is indicated if the FRS is greater than 2.0 (15, e15). The FRS is derived from a combination of clinical data (age, smoking status, blood pressure) and laboratory values (total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol).

Box 4. Indications for stress ECG in asymptomatic persons (without any known coronary heart disease).

Class I: None

-

Class II:

Presence of multiple risk factors

Age over 45 years (men) or 55 years (women)

Before physical training

Occupations in which heart disease could endanger public safety

High likelihood of coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, chronic renal failure, etc.

Class III: Routine examination of asymptomatic persons (15, 20, e14)

The AHA generally does not consider stress ECG testing mandatory for asymptomatic persons about to undergo moderate training, as the risks of such training are low, while the test is expensive and unlikely to yield useful information, and the interpretation of its findings is fraught with uncertainty (20). Thus, stress ECG testing should be performed only in accordance with the guidelines, and attention should be paid to quality control. A common error in stress ECG testing is inadequate stress (12, 15, 18– 20, e14, e33, e34). For overweight or obese persons, the current state of the data on stress ECG testing is uncertain, but the same recommendations are in effect, so that cardiac events can be prevented in this group at elevated risk.

Repeating the pre-participation examination

No prospective studies shed light on the question whether the sports-medicine pre-participation examination should be repeated, and, if so, when. The current literature consistently recommends repeating the preventive examination as follows:

every 2–3 years in persons under age 35;

every 1–2 years in persons over age 35, or who have more than one risk factor, or whose examination reveals an abnormal finding (4, 12, e14, e27);

persons who have developed new symptoms or signs of disease should undergo an additional short-term examination.

Overview

The content and extent of the pre-participation examination in sports medicine are currently debated in the USA and Europe, particularly with respect to the ECG at rest; the cost factor plays a much larger role in the USA (13, 21– 24, e24– e26, e30, e35, e36, e38, e39). To date, there have not been any large-scale, prospective, multi-center cohort studies with hard endpoints (mortality and cardiac morbidity) and with long-term follow-up of defined groups of athletes. Such studies will be needed for an accurate determination of the costs and benefits of preventive testing, and, in turn, for a judgment of its proper extent. It is recommended that the ”Check-up 35” now routinely performed in Germany should be supplemented with a pre-participation sports-medicine examination serving the aims of disease prevention, suitability testing for sports, life-style counseling, and counseling for athletic training.

In Germany, as elsewhere, figures on the frequency of medical complications in sports are lacking. In sporting events that involve large numbers of people, such as city marathons, the participants’ medical care and their rate of complications should be prospectively studied with the aid of an anonymized questionnaire filled out by the organizers. This is the only way to determine the risk of participating in sporting events such as community runs, marathons, or triathlons, and to gauge the utility of preventive medical examinations. Such prospective studies will require the collaboration of event organizers and medical rescue services. A questionnaire of this type already exists (personal communication from T. Rüther). In cases of sudden death during sporting activity, a maximally standardized medicolegal autopsy, including a so-called molecular autopsy, might yield important findings (9, 10).

For ethical, medicolegal, and medical reasons, there is now a consensus recommendation (IIa, C) for a pre-participation sports-medicine examination; the proposed standard consists of a uniformly obtained clinical history, physical examination, and ECG at rest interpreted by a qualified specialist. This proposed standard is based on the recommendations of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and of the American and European societies of cardiology, sports medicine, and pediatrics. Public organizations, governmental authorities, the World Health Organization, medical societies, and associations of sports physicians currently advise everyone to take regular physical exercise for the primary prevention of disease. It follows that anyone willing to take this advice should be offered a preventive medical examination, in qualified hands, to minimize the avoidable cardiac risk.

Acknowledgments

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Professor W. Hollmann on the occasion of his eighty-fifth birthday.

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Löllgen has received lecture honoraria from BayerVital.

The other authors state that they have no conflict of interest as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Leyk D, Rüther T, Wunderlich M, Sievert AP, Erley OM, Löllgen H. Utilization and implementation of sports medical screening examinations. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(36):609–614. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardio-myopathies: An American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006;113:1807–1816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Zipes DP. 36th Bethesda Conference: Eligibility recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1312–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrado D, Basso C, Schiavon M, Pellicia A, Thiene G. Pre-Participation screening of young competitive athletes for prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1981–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pellicia A, Zipes DP, Maron BJ. Bethesda conference #36 and the European Society of Cardiology consensus recommendations revisited: A comparison of U.S. and European criteria for eligibility and disqualification of competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1990–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priori SG, Zipes DP. Malden. Massachusetts: Blackwell; 2006. Sudden cardiac death. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löllgen H, Gerke R, Steinberg T. Der kardiale Zwischenfall im Sport. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103(23):A 1617–A1621. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Circulation. 2009;119:1085–1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. The role of molecular autopsy in unexplained sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:166–172. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221576.33501.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tester DJ, Ackermann MJ. Postmortem long QT syndrome genetic testing for sudden unexplained death in the youth. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syris P, Prasad S, et al. Left dominant -arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2175–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Löllgen H, Hansel J. Vorsorgeuntersuchung bei Sporttreibenden. S1-Leitlinie, 2007, DGSP; wwwd.gsp.de oder www.prof-loellgen.de [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drezner JA. Contemporary approaches to the identification of -athletes at risk for sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008:494–501. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32830b3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson MG, Basavarjaiah S, Whyte GP, Cox S, Loosemore M, Sharma S. Efficacy of personal symptom and family history questionnaire when screening for inherited cardiac pathologies: the role of electrocardiography. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:207–211. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.039420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT. ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines update for exercise testing. Summary article. Circulation. 2002:883–892. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034670.06526.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Löllgen H, Erdmann E, Gitt A. 3rd edition. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2009. Ergometrie. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viskin S, Rosovki U, Sands AJ. Inaccurate electrocardiographic interpretation of long QT: the majority of physicans cannot recognize a long QT when they see one. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaitman BR. An electrocardiogram should not be included in routine preparticipation screening of young athletes. Circulation. 2007;16:2610–2615. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myerburg RJ, Vetter VL. Electrocardiograms should be included in preparticipation screening of athletes. Circulation. 2007;16:2616–2626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haskell W, Lee I-M, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public -health. Circulation. 2007;16:1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maron BJ, Thompson PD, Puffer JC. Cardiovascular preparticipation screening of competitive athletes: Addendum. Circulation. 97:998–2294. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maron BJ, et al. Recommendations for preparticipation screening and the assessment of cardiovascular disease in masters athletes. Circulation. 2001;101:327–334. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellicia A, Maron BJ. Preparticipation cardiovascular evaluation of the competitive athlete: perspectives from the 30-year Italian -experience. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:827–829. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sofi FA, Capalbo A, Pucci N, et al. Cardiovascular evaluation, including resting and exercise electrocardiography, before participation in competitive sports. cross sectional study BMJ. 2008;337:88–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Corrado D, et al. Consensus statement of the study group of sport cardiology of the working group of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise physiology and the working group of myocardial and pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 26. 2005:516–524. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Pellicia A, Saner H. Participation in leisure-time physical activities and competitive sports in patients with cardiovascular diseases: How to get the benefits without risks. Europ J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2005;12:315–317. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000174825.94892.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, Michieli P, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006;296:1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Maron BJ. How should we screen competitive athletes for cardiovascular disease? Europ Heart J. 2005;8:516–524. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Maron BJ, Douglas PS, Graham TP, et al. Task Force 1: Preparticipation screening and diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1322–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Estes NMA, Salem DN, Wang PJ, editors. Sudden cardiac death in the athlete. Armonk NY. Futura Publishing Company. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- e7.Schmitt C, Merkel M, Wondrascheck R, Riexinger T, Luik A. Plötzlicher Herztod bei Jugendlichen und Sportlern. Kardiologie Update. 2009;5:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- e8.Klot S v, Mittleman MA, Dockery DW, et al. Intensity of physical exertion and triggering of myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Marti B. Plötzliche Todesfälle an Schweizer Volksläufen 1978-1987. Schweiz Med Wschr. 1989;119:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Puranik R, Chow CK, Duflou JA. Sudden death in the young. Heart Rhythm. 2005:1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Eckart RE, Scoville SL, Campbell CL. Sudden death in young adults: a 25 year review of autopsy in military recruits 2004. Ann Intern Med. 141:829–834. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC. Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinical, demographic and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Cardinal B. Assessing the physical activity readiness of inactive older adults. Appl Phys Act Quarterly. 1997;14:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- e14.Maron BJ, Araujo CG, Thompson PD, et al. Recommendations for preparticipation screening and the assessment of cardiovascular disease in masters athletes: an advisory for healthcare professionals from the working groups of the World Heart Federation, the International Federation of Sports Medicine, and the American Heart Association Committee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation. 2001;103:327–334. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.ACSM guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. (American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- e16.Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. New Engl J Med. 1984;311:874–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79:733–743. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Tofler GH. Estes NMA, Salem DN, Wang PJ, editors. Triggers of sudden cardiac death in the athlete: Sudden cardiac death in the athlete. Armonk NY. Futura Publishing Company. 1998:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- e19.Papadakis M, Whyte G, Sharma S. Preparticipation screening for cardiovascular abnormalities in young competitive athletes. Brit Med J. 2008;337:806–811. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Maron BJ, Epstein SE, Roberts WC. Causes of sudden death in competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:204–214. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts W, Nuekker P. Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Noronha Sv de, Sharma S, Papadakis M, Desai S, Whyte G, Sheppard MN. Aetiology of sudden death in athletes in the United Kingdom: a pathological study. Heart. 2009;25:1409–1414. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.168369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Pelliccia A, Culasso F, Di Paolo M, et al. Prevalence of abnormal electrocardiograms in a large, unselected population undergoing pre-participation cardiovascular screening. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2006–2010. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Fuller CM, McNulty CM, Spring DA, et al. Prospective screening of 5615 high scholl athletes for risk of sudden cardiac death. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1997;29:1131–1138. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Maron BJ, Mittleman MA, Pelliccia A. Placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2358–2368. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Nora M, Zimmermann F, Ow P, Fenner P, Marek J. Abstract 3718: Preliminary findings of ECG screening in 9125 young adults -Circulation. 2007;116 [Google Scholar]

- e27.Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, et al. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1687–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Kindermann W, Dickhuth HH, Nies A, Röcker A, Urhausen A, editors. 2nd edition. Darmstadt: Steinkopf; 2004. Sportkardiologie. [Google Scholar]

- e29.Dickhuth HH, Mayer F, Röcker K, Berg A, editors. Sportmedizin für Ärzte. Köln. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- e30.Pelliccia A. The preparticipation cardiovascular screening of competitive athletes: is it time to change the customary clinical practice? Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2703–2705. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Bille K, Figueiras D, Schamasch P, et al. Sudden cardiac death in athletes: The Lausanne Recommendations. Europ J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2006;13:859–875. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000238397.50341.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.IOC (Int. Olymp. Committee) Lausanne. 2004. Sudden cardiovascular death in sport. Preparticipation screening IOC Medical Commission (eds.) [Google Scholar]

- e33.Löllgen H. 4th edition. Nürnberg: Novartis; 2005. Kardiopulmonale Funktionsdiagnostik. [Google Scholar]

- e34.Trappe H-J, Löllgen H. Leitlinien zur Ergometrie. Z Kardiol. 2000;89:821–837. doi: 10.1007/s003920070190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Kjaer M. Sudden cardiac death associated with sports in young individuals: Is screening the way to avoid it? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Hernelahti M, Heinonen OJ, Karjalainen J, Nylander J, Börjesson M. Sudden cardiac death in young athletes: time for a Nordic approach in screening? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Waller BF, Roberts WC. Sudden death while running in conditioned runners age 40 years or over. Am J Cardiol. 1980;45:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Maron BJ, Thompson PD, Puffer JC, et al. A statement for health professionals from the Sudden Death Committee (clinical cardiology) and Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee (cardiovascular disease in the young), American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;15:850–856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Corrado D, Basso C, Thiene G. Sudden cardiac death in young people with apparently normalheart. Cardiovasc res. 2001;50:399–408. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]