Abstract

In Drosophila melanogaster, hypomorphic mutations in the gap gene giant (gt) have long been known to affect ecdysone titers resulting in developmental delay and the production of large (giant) larvae, pupae and adults. However, the mechanism by which gt regulates ecdysone production has remained elusive. Here we show that hypomorphic gt mutations lead to ecdysone deficiency and developmental delay by affecting the specification of the PG neurons that produce prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH). The gt1 hypomorphic mutation leads to random loss of PTTH production in one or more of the 4 PG neurons in the larval brain. In cases where PTTH production is lost in all four PG neurons, delayed development and giant larvae are produced. Since immunostaining shows no evidence for Gt expression in the PG neurons once PTTH production is detectable, it is unlikely that Gt directly regulates PTTH expression. Instead, we find that innervation of the prothoracic gland by the PG neurons is absent in gt hypomorphic larvae that do not express PTTH. In addition, PG neuron axon fasciculation is abnormal in many gt hypomorphic larvae. Since several other anteriorly expressed gap genes such as tailless and orthodenticle have previously been found to affect the fate of the cebral labrum, a region of the brain that gives rise to the neuroendocrine cells that innervate the ring gland, we conclude that gt likely controls ecdysone production indirectly by contributing the peptidergic phenotype of the PTTH-producing neurons in the embryo.

Keywords: giant, ecdysone, prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH), axon guidance, ring gland, prothoracic gland, developmental delay

Introduction

The giant (gt) locus codes for a zinc finger containing transcription factor that is widely known for its role in specifying early anterior/posterior pattern in the blastoderm embryo (Capovilla et al., 1992; Eldon and Pirrotta, 1991; Reinitz and Levine, 1990; Stanojevic et al., 1991). Amorphic gt alleles lead to embryonic lethality due to the loss of posterior abdominal segments 5–7 and sometimes 8, as well as labral and labial structures in the head region. (Gergen and Wieschaus, 1985; Mohler et al., 1989; Petschek et al., 1987). However, the original gt alleles were discovered and partially characterized as mutations that produced large larvae as a result of developmental delay (Bridges, 1928). These mutants played an important role in the early history of Drosophila genetics because they also produced larger than normal polytene chromosomes that aided early cytogenetic studies (Bridges, 1935).

The viable gt alleles exhibit variable penetrance (~25% females, 13% males) that can be enhanced in females when placed over a deficiency, suggesting that they are hypomorphic mutations that enable some mutant larvae to survive past the early essential embryonic requirement for gt (Schwartz et al., 1984). These larvae exhibit pronounced developmental delay especially during the third instar stage and pupate approximately 5 days later than wildtype (Schwartz et al., 1984).

Post-embryonic development in holometabolous insects is characterized by defined molting periods followed by metamorphosis. The precise timing of these events is regulated at a systemic level in response to multiple cues such as nutritional status, body size, organ development and environmental conditions (Edgar, 2006; Menut et al., 2007; Mirth and Riddiford, 2007; Nijhout, 2003). These cues likely regulate developmental timing in several ways, but ultimately they impinge upon the production and secretion of the insect steroid hormone ecdysone. In gt hypomorphic larvae, the protracted third instar stage appears to result from a delay in the rise of ecdysone titer that precedes the initiation of metamorphosis, since feeding these animals 20-hydroxecdysone (20-E) reverts the delay phenotype leading to normal size larvae that pupate at the appropriate time (Schwartz et al., 1984).

The molecular mechanism by which gt controls ecdysone production has been a longstanding mystery. In many insects, the regulation of ecdysone production in larvae involves two major components: a pair of bilaterally symmetric neurons (PG neurons) located in the cebral labrum portion of the brain, and the prothoracic gland, the endocrine organ that actually produces and secretes ecdysone (Gilbert et al., 2002). In Drosophila, the PG neurons directly innervate the prothoracic gland (Siegmund and Korge, 2001) and induce production and secretion of ecdysone by releasing an adenotropic peptide hormone called prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) (McBrayer et al., 2007). PTTH signals through the receptor tyrosine kinase Torso to activate a RAS/ERK cascade that ultimately stimulates transcription of ecdysone biosynthetic enzymes (Rewitz et al., 2009). Intriguingly, elimination of PTTH signaling delays the rise in ecdysone titer and the onset of pupation by approximately 5 days resulting in large pupae and adults, similar to those produced by gt hypomorphs (McBrayer et al., 2007; Rewitz et al., 2009). The similarity in phenotype between gt hypomorphs and loss of PTTH signaling prompted us to investigate whether gt in some way controls PTTH signaling. Here we report that rather than directly regulating PTTH production in the PG neurons, gt indirectly controls PTTH and subsequent ecdysone production by influencing the development of the PTTH-producing PG neurons.

Materials and methods

Drosophila stocks and husbandry

The gt1 and gtE6 lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila stock center. gt1; ptth-HA stocks were generated by standard genetic methods. Genomic ptth-HA-50A line (yw; ptth-HA) and the yw; Feb211-Gal4; UAS-GFP (Feb211-GFP) line were described previously (McBrayer et al., 2007; Siegmund and Korge, 2001). gt1;UAS-GFP;Feb211-Gal4 larvae were obtained by crossing Feb211-GFP males to gt1 females and selecting male larvae. Flies were raised at 25°C on standard food in vials.

Immunohistochemistry

The following antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions for immunohistochemistry: rat anti-HA 3F10 (Roche) 1/500, rat anti-Gt (generous gift from Dr. Vincenzo Pirrotta) 1/500 and mouse anti-CSP (Iowa Hybridoma Bank) 1/100. The Alexa series (Invitrogen) of secondary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence at 1/500 dilution. CNSs from third instar wandering larvae were dissected out and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature for anti-HA and anti-CSP staining. Antibody staining and washes of larval CNSs were conducted in 0.1% Triton-X100 in 1X PBS (PBST). Primary antibody treatments of CNSs were done at 4°C for 24 hours. Embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes and all subsequent antibody reactions were in PBS + 0.1% Tween-20. Samples were mounted in 80% glycerol in PBS and visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 with a CARV unit for confocal microscopy.

Results and discussion

Hypomorphic mutations in giant show stochastic elimination of PTTH expression in PG neurons

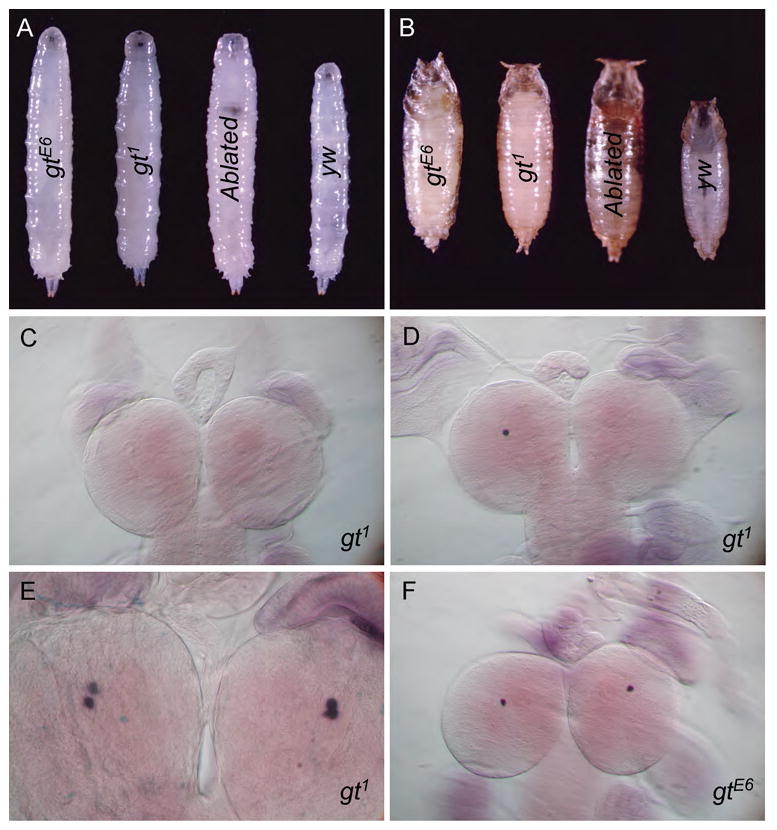

The phenotypes seen in gt hypomorphic alleles (Schwartz et al., 1984), although less penetrant, are remarkably similar to those described for loss of the PTTH-producing PG neurons or PTTH signal transduction components. These include a developmental delay and low ecdysone titers during the prolonged third instar stage, production of large larvae, pupa and adults, and the ability to rescue these phenotypes by feeding larvae 20HE (Fig. 1A and B, (McBrayer et al., 2007; Rewitz et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 1984). To examine if loss of gt affected the expression of PTTH in the PG neurons, we carried out in situ hybridization using a ptth probe on brains of hypomorphic gt1 or gtE6 mutants prepared from wandering third instar or large feeding larvae. Similar in situ hybridization experiments with wild type CNSs show four distinct ptth producing PG neurons, two in each brain lobe (McBrayer et al., 2007). However, gt mutant larva containing hypomorphic alleles revealed varying degrees of abnormal ptth expression depending on the individual larvae and mutant allele. Hemizygous gt1 male mutant larva display the most variability with approximately one third of the larvae exhibiting a developmental delay phenotype that correlates with either one or no cell expressing ptth (Fig. 1C and D). Other larvae that were not excessively large, exhibit relatively normal ptth expression (Fig. 1E). Individuals containing the gtE6 allele frequently exhibited expression within only one cell of the pair of bilateral PTTH-expressing neurons within each brain hemisphere instead of the usual two (Fig. 1F). We conclude that the similarity in phenotype between ablation of PG neurons and the gt hypomorphic mutants and the semi-penetrant phenotype of the gt hypomorphic allele is likely caused by the partial loss of ptth expression in the PG neurons. As shown previously (McBrayer et al., 2007), the loss of the ptth neurons leads to a defect in the expression of many ecdysone biosynthetic enzymes which likely accounts for the low and delayed peak in ecdysone titer and a delayed onset of metamorphosis in gt hypomorphs (Schwartz et al., 1984).

Figure 1. Hypomorphic giant mutants are phenotypically similar to PG neuron ablated flies and show variable loss of PTTH expression in the PG neurons.

gt1 and gtE6 larvae exhibit a prolonged third instar stage in about 25% of females and 13% of males. This phenotype, although much less penetrant, is similar to PG neuron ablated larvae (ptth>Gal4/UAS-grim). This prolonged third instar stage gives rise to larvae and pupae that are significantly larger than yw control animals (A and B, pictures were taken at same magnification and settings and fused using Photoshop). Consistently, ptth expression, as observed by in situ hybridization, is lost from all four PG neurons in the developmentally delayed gt1 larvae (C). Normally developing gt hypomorphic larvae show a variable stochastic loss of ptth expression ranging from one-three of the four PG neurons (D–E). Many of them express ptth in all four PG neurons similar to wild type animals (E) and most of these animals show no developmental delay.

Gt is not expressed in PTTH-producing neurons or the prothoracic gland

Since gt encodes a zinc finger-containing DNA binding factor, one possible explanation for loss of ptth expression in the PG neurons of gt hypomorphic mutants is that Gt directly controls ptth transcription. Alternatively, Gt could indirectly regulate ptth transcription by several possible mechanisms. For example, in the late embryo, gt has been reported to be expressed in the ring gland (Capovilla et al., 1992). The ring gland expression is intriguing since one way to restrict ptth expression to only the two neurons that innervate the prothoracic gland is by delivery of a required retrograde signal from the target tissue. Such a mechanism is involved in regulating the peptidergic phenotype of the FMRF producing Tv neurons (Allan et al., 2003; Marques, 2003), and perhaps gt expression in the ring gland could play an analogous role in regulating a retrograde signal that controls ptth expression.

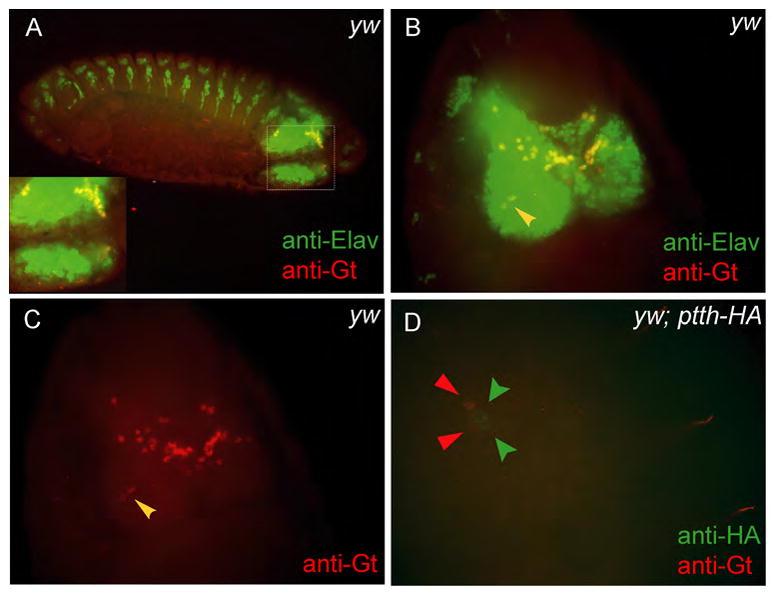

To address these possibilities, we used immuno-staining to examine Gt expression in both larvae and embryos. We found no evidence for Gt expression in larval or embryonic prothoracic glands (data not shown) or in the larval PG neurons. In the embryo we detect dynamic expression of Gt in various portions of the developing brain (Fig. 2A, B and D). At stage 14 there are two prominent Gt-expressing neurons in the lateral portion of each brain hemisphere that could be either the PG neurons or perhaps their precursors (Fig. 2B and C, yellow arrowheads). To examine this issue, we attempted to double stain embryonic brains for Gt and PTTH using a transgenic line that expresses an HA-tagged form of PTTH (McBrayer et al., 2007). However, embryonic expression of PTTH-HA in the PG neurons does not begin until approximately stage 17–18, and at this time we no longer detect consistent Gt expression in the brain. In a few rare embryos we do see simultaneous Gt and PTTH staining within the brain but they are in adjacent non-overlapping cells (Fig. 2D, red and green arrowheads showing Gt and PTTH-HA expressing cells respectively). We conclude that Gt is unlikely to directly regulate ptth transcription in the PG neurons or indirectly regulate ptth expression via production of a retrograde signal from the prothoracic gland since neither the prothoracic glands nor the PG neurons co-express Gt and PTTH. We suspect that the previously-reported expression of Gt in the embryonic ring gland (Eldon and Pirrotta, 1991) was a misidentified portion of the dorsal brain.

Figure 2. Giant is expressed in the embryonic brain including two neurons adjacent to the PG neurons.

Co-staining wild-type embryos with anti-Elav (a pan-neuronal marker) and anti-Gt show that Gt is expressed in the developing embryonic brain even at late embryonic stages (A). At stage 14 there are two prominent Gt-expressing neurons in the lateral portion of each brain lobe, positioned ideally to be either the PG neurons themselves or precursors to PG neurons (B and C (red channel from B), yellow arrowheads). To check if the PG neurons in the embryo express Gt, PTTH-HA expressing embryos were co-stained with anti-HA and anti-Gt antibodies (D). PTTH-HA expression is seen very late during embryogenesis by which time Gt expression fades. However, on rare occasions two Gt expressing cells (red arrowheads) could be seen right next to the PTTH-HA expressing PG neurons (green arrowheads) (D).

gt1 affects the development of PTTH-producing neurons

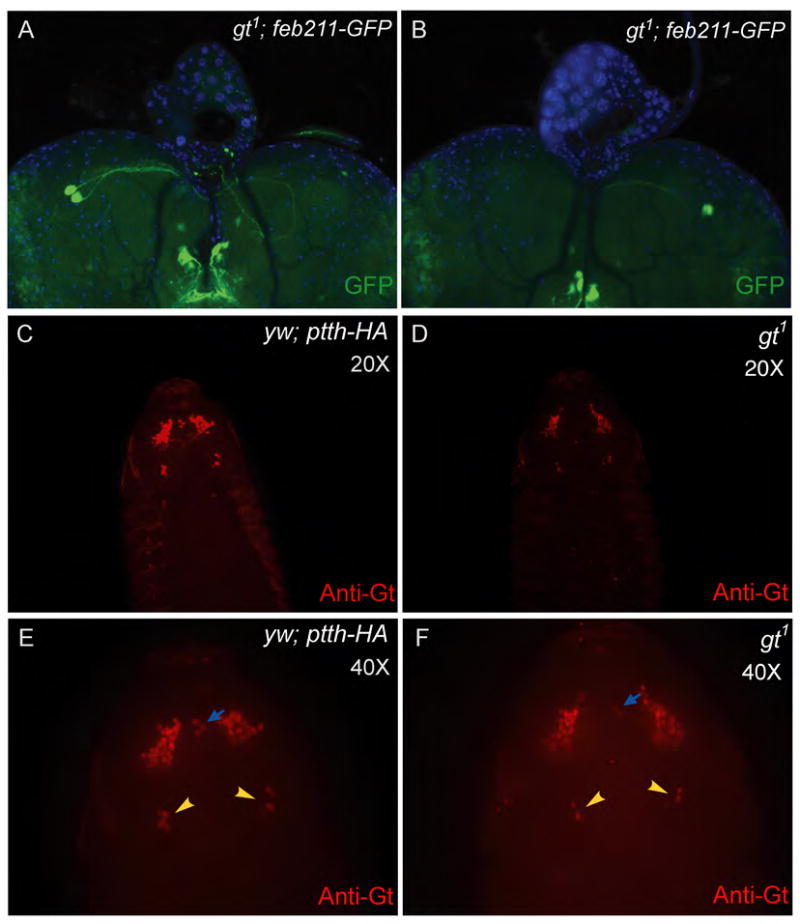

In the absence of any evidence supporting a role for Gt in regulating ptth transcription, we sought to determine if loss of Gt affects the specification of PG neurons. Besides ptth, the only other described marker for PG neuron fate is the Feb211-Gal4 enhancer trap line (Siegmund and Korge, 2001) that contains an insertion into an unknown gene on chromosome 3. Analysis of expression from this enhancer line in gt1 mutant larvae revealed a similar stochastic loss of GFP expression in different numbers of PG neurons as seen for ptth expression itself (Fig. 3, A and B). The all or none response observed for both ptth and Feb211-Gal4 expression in gt hypomorphs is consistent with a stochastic loss of PG neurons in these mutants.

Figure 3. Hyomorphic mutations in gt affects expression of an independent PG neuron marker Feb211-GFP and may affect PG neuron development by an expression threshold effect.

In a gt1 background Feb211-GFP expression is lost in a stochastic manner identical to ptth in figure 1(A and B) indicating that the fate of the PG neurons may be affected and not just ptth expression. A comparison of Gt immunostaining intensity between control and gt1 embryos indicates that Gt expression is reduced in the gt1 embryo (C and D, exposure time: C (1.693 sec) and D (1.754 sec). At higher magnification, and increased exposure time, the gt1 embryo in D shows loss of Gt expression in several bilaterally symmetric Gt-expressing cells (E and F, yellow arrowheads). Loss of Gt is also seen in a cluster of three cells positioned anteriorly (E and F, blue arrows).

The gt1 mutation has been shown to be associated with two spontaneous insertions, one near the 5′ region of the gene and the other in the 3′ region (Mohler et al., 1989). We predict that these insertions likely affect gt expression levels during embryogenesis, and altered gt expression may affect the specification of different neuron subtypes within the brain including precursors that give rise to the PG neurons. To examine this issue in more detail, we sought to determine if Gt expression is reduced or if fewer cells express Gt in gt1 mutant animals compared to wild type embryos. Figure 3(C–F) shows a comparison between control and gt1 stage 13 embryos. We observe that under identical staining and exposure conditions, Gt staining intensity in the control embryo is stronger compared to the gt1 embryo (Figure: 3 C and D). The primary staining is in an anterior medial position that is anatomically close to or overlapping with the pars intercerebralis (PI) and pars lateralis (PL) region of the brain that gives rise to a number of neurosecretory cells including several neurons that innervate the corpus cardaicum and corpus allatum, two other portions of the ring gland (de Velasco et al., 2007). The PI placode derives from neuroepithilium that expresses tailless and orthodenticle, two anteriorly expressed gap genes. The exact origin of the PG neurons has not been established, but they may be derived from two other placodes that reside more posterior to the PI region (de Velasco et al., 2007). Interestingly, we note a prominent cluster of approximately 5 bilateral posterior midline neurons that express Gt in stage 13 embryos (Fig 3E, yellow arrowheads). In equivalently staged gt1 mutant embryos (Fig. 3F), the number of cells in this cluster that express Gt is reduced to two to four cells (Fig. 3F, yellow arrowheads). Similarly, staining of a cluster of three cells positioned anteriorly on the midline axis (Fig. 3E and F, blue arrows) is also dramatically reduced in the gt1 sample.

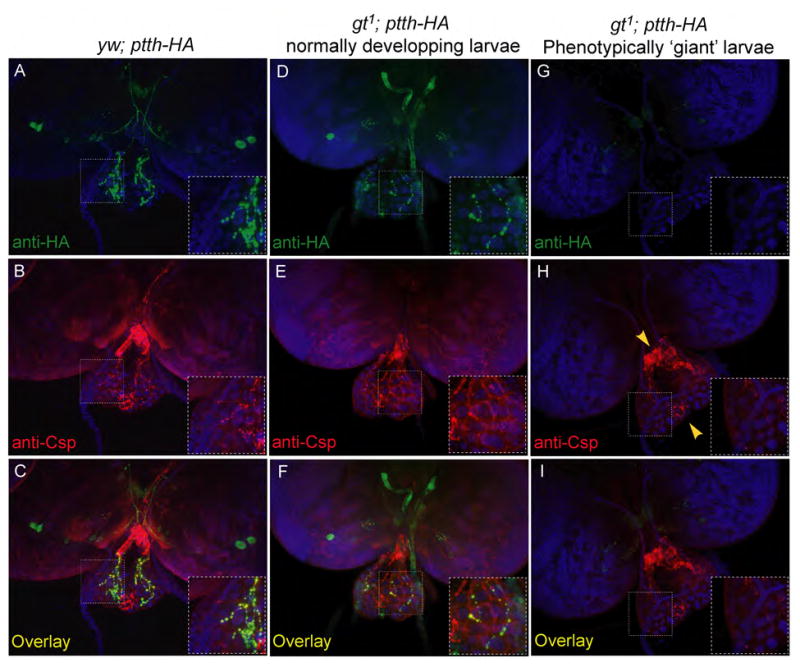

These results suggest that the specification of multiple neuron subtypes in the brain is likely affected in the gt1 mutant animals. Since we have no lineage tracers available to directly determine if the PG neurons are derived from earlier precursors that express Gt, we used an indirect assay to determine if PG neurons are mis-specified in gt1 hypomorphs. Previous axon tracing experiments have revealed that the PG neurons are the only neurons that innervate the prothoracic gland (Siegmund and Korge, 2001). To determine if gt affects the specification of PG neurons, we examined cysteine string protein (Csp) distribution on ring gland cells. Csp is enriched in synaptic boutons. As shown in Figure 4(A–C) Csp co-localizes with PTTH in axon terminals and boutons on the surface of wildtype prothoracic gland cells as well as in gt1 mutant larvae that still show PTTH expression (Fig. 4D–F). In contrast, developmentally delayed gt1 larvae in which PTTH expression is absent from all 4 PG neurons, no Csp-containing boutons are observed on prothoracic gland cells (Fig. 4G–I). In these same larvae however, Csp-containing axons and boutons are still seen within the corpus cardiacum and corpus allatum, two regions of the ring gland that are innervated by different sets of neurons (Fig. 4H, yellow arrowheads (Siegmund and Korge, 2001). We conclude that loss of Gt affects the development of the PG neurons since its absence leads to a loss of prothoracic gland innervation. At this point, we cannot distinguish if Gt directly affects the specification of PG neurons, or if it affects PG neuron development in a cell non-autonomous manner, perhaps by affecting cell-cell interactions during early cortex development. Nevertheless, these experiments add gt to the list of anteriorly expressed gap genes that affect the specification of the proto-cerebrum (Younossi-Hartenstein et al., 1997).

Figure 4. gt1 affects fate of the PTTH-producing PG neurons.

gt1 and yw control larvae expressing PTTH-HA under the endogenous ptth promoter were co-stained with anti-HA and anti-CSP (cysteine string protein) antibodies. PTTH-HA staining is clearly seen in the PG neurons, and sites of innervation on the prothoracic gland in the yw control larvae and in gt1; ptth-HA larvae that develop normally (A and D). CSP co-localizes to the sites of innervation by the PG neurons on the prothoracic glands of these larvae (B, C, E and F). gt1 larvae that manifest the ‘giant’ phenotype do not show any PTTH-HA staining either on the brain lobes where the PG neurons are located or on the prothoracic glands (G). Csp staining is also absent on the prothoracic glands of these larvae indicating a loss of innervation by the PG neurons (H and I). However, Csp staining is still visible on the corpus cardiacum and the corpus allatum that are innervated by a different set of neurons than the PG neurons (H, yellow arrowheads).

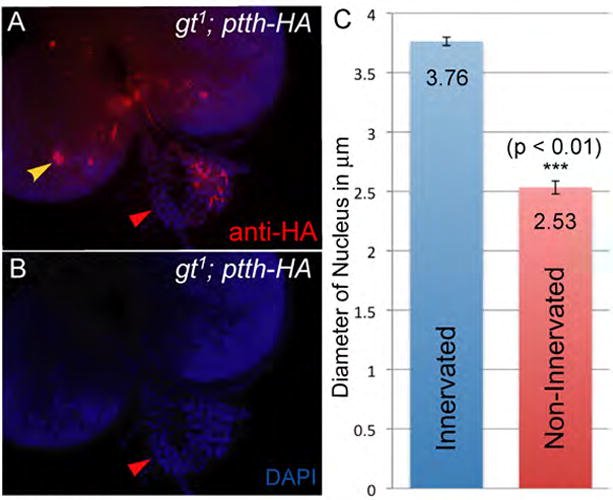

PG neurons provide a tropic signal to the prothoracic gland

In Manduca sexta PTTH is believed to have a tropic effect on the larval prothoracic gland as it has been shown to induce general protein synthesis (Rybczynski and Gilbert, 1994). Similar to Manduca sexta, prothoracic gland cells in Drosophila are mitotically quiescent during larval stages. Nevertheless, the gland cells exhibit substantial growth during the three larval stages and this growth is characterized by the formation of polytene chromosomes and an increase in size of the gland cells (Aggarwal and King, 1969). We observed that gt1 mutant larvae exhibiting unilateral innervation of the prothoracic glands consistently produced an asymmetrically sized gland in which the innervated portion was significantly larger than the non-innervated side (Fig. 5). Measuring the diameter of DAPI stained nuclei revealed that cells on the non-innervated side contained nuclei that are significantly smaller compared to the innervated side (Fig. 5B and C). This difference was consistently observed in all samples that failed to innervate one of the prothoracic glands indicating that DNA synthesis is likely reduced in absence of prothoracic gland innervation. Curiously, as previously reported (McBrayer et al., 2007) when both sides lacked innervation, the ring gland did not appear substantially smaller than wild type (compare Fig: 4 C and I). However these glands are from developmentally delayed larvae in which the extra growth time likely enables them to “catch up” to the wildtype in terms of prothoracic gland size. Ultimately we will need to examine PTTH null mutants to prove that PTTH, and not some other factor, is the tropic signal secreted from the PG neurons. However, the recent finding that PTTH signals through the Drosophila receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Torso is certainly consistent with the idea that PTTH is the tropic factor since the Torso signal is transduced through the canonical Ras-Raf-ERK pathway (Rewitz et al., 2009) which is known to regulate cell proliferation in many systems (reviewed in, McCubrey et al., 2007).

Figure 5. gt1 hypomorphs reveal that the PG neurons relay a tropic signal to the prothoracic glands that promotes growth.

gt1; ptth-HA CNSs containing only one set of PG neurons (A, yellow arrowhead) mostly innervate only one of the prothoracic glands. The innervated prothoracic gland serves as an internal control for any growth promoting effect of the PG neurons. DAPI staining of these samples show that the prothoracic gland that is not innervated is consistently smaller than the control prothoracic gland (A and B) indicating that the PG neurons provide a tropic signal to the prothoracic glands. The cells in the non-innervated prothoracic gland have much smaller nuclei (B red arrowhead) indicating impaired DNA synthesis. To quantify the difference in size, we determined nuclei diameter for 12 nuclei from one PG and considered the average of these measurements as a single data point representing PG size. PG size was similarly calculated for innervated and non-innervated PGs from three independent brain ring glands complexes. The mean of these measurements is plotted (C) and shows that nuclei within non-innervated PGs are significantly smaller (p-value = 0.005). Significance was calculated using a paired student t-test to negate the effect of variations in PG size between the three samples.

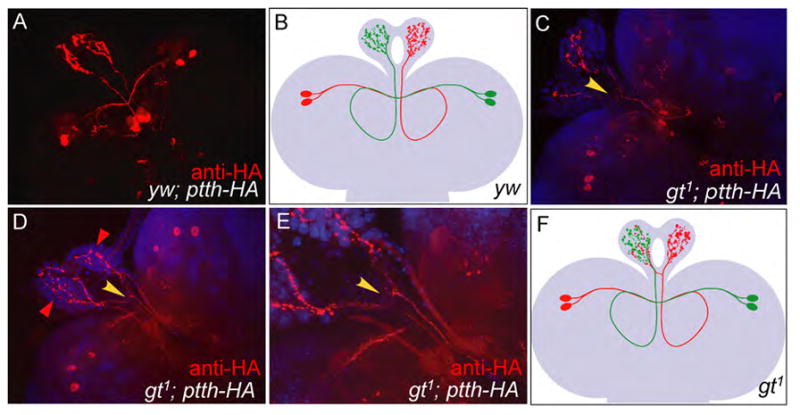

Residual PG neurons show enhanced axon misrouting in gt1 mutant larvae

In addition to the absence of prothoracic gland innervation in many gt1 hypomorphic larvae, we noted that there is an enhanced frequency of axon misrouting in gt mutant larvae that still show ptth-HA expression in one or more of their PG neurons. In wild type larvae, the polarized PG neurons in the left lobe of the brain send out their axons from the cell body across the central axis of the CNS to the right brain lobe. There the axon forms a loop with a left hand twist and then projects anteriorly to innervate the prothoracic gland cells on the right half of the ring gland (Fig. 6A, B and Siegmund & Korge, 2001). Similarly the neurons in the right lobe extend their axons into the left lobe and innervate the left half of the ring gland. This innervation pattern is most clearly revealed in gt1 mutant larvae retaining one pair of the bilateral PG neurons. For example, in a gt1 mutant larva that retains the right side set of PG neurons, there is innervation only within the left prothoracic gland (Fig. 5A). In wild type larvae, the axon tracts from each pair of PG neurons are almost parallel to each other at the base of the ring gland and rarely exhibit cross (only 1 out of 23 CNSs from wt controls showed branching). However, in the gt1 CNSs containing one or two PG neurons in only one brain lobe, we often see the axons branching at the base of the ring gland and innervating both prothoracic glands (Fig. 6C, yellow arrowhead). Interestingly we observed similar branching events in gt1 samples that have all four PG neurons (Fig. 6D and E, yellow arrowhead). This suggests that the cross innervations are not likely to be caused by a mechanism that tries to compensate for the lack of innervation on one side of the prothoracic gland. Consistent with this view, we find that in certain cases such branching events caused excessive innervation of one of the prothoracic glands at the cost of the other (Fig. 6D, red arrowheads). Approximately 24% of gt1 CNSs that retained at least one PG neurons showed cross innervation events with clear branching at the base of the ring gland.

Figure 6. PG neurons in gt1 hypomorphs exhibit an increased frequency of axon misrouting.

Anti-HA staining (red) of yw; ptth-HA CNS shows that axon projections from PG neurons follow a well defined path with the PG neurons in the left lobe of the brain innervating the right prothoracic gland and vice versa (A, modeled in B). Similar staining of gt1; ptth-HA CNSs show that gt1 mutants containing one or two PG neurons in one of the brain lobes often show branching of axons at the base of the ring gland (C, yellow arrowhead). Such branching is also observed in gt1; ptth-HA CNSs that retain all the four PG neurons and, in certain cases, leads to excessive innervation of one of the prothoracic glands at the cost of the other (D, red arrowheads). An enlargement of the base of the ring gland in C clearly shows the branching (E, yellow arrowhead). For a better understanding of the branching pattern a model of gt1 CNS showing axon branching is provided (F). While the model shows axons from only the red PG neurons cross innervating the PGs, either side or both sets of axon bundles are capable of branching at the base of the PG in gt mutant larva.

These results suggest that gt is required not only for correct specification of the PG neurons, but also influences the projection of PG neurites to their target tissue. At present, we cannot distinguish if these axon guidance defects represent reduction in the expression of intrinsic factors within the PG neurons that respond to guidance cues or whether Gt not only affects the specification of the PG neurons themselves, but also surrounding neurons that might provide guidance cues. Ultimately, lineage tracing experiments will be required to determine which neurons are descendent from Gt-expressing cells in order to address these issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Naoki Yamanaka, Aidan Peterson and MaryJane Shimell for comments on the manuscript. MBO is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggarwal SK, King RC. Comparative study of the ring glands from wild type and 1(2)gl mutant drosophila melanogaster. J Morphol. 1969;129:171–99. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan DW, St Pierre SE, Miguel-Aliaga I, Thor S. Specification of neuropeptide cell identity by the integration of retrograde BMP signaling and a combinatorial transcription factor code. Cell. 2003;113:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CB, Gabritschevsky E. The giant mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Part I. The heredity of giant. Z Indukt Abstamm Vererbungsl. 1928;46:231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CB. Salavary chromosome maps. J Hered. 1935;26:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla M, Eldon ED, Pirrotta V. The giant gene of Drosophila encodes a b-ZIP DNA-binding protein that regulates the expression of other segmentation gap genes. Development. 1992;114:99–112. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Velasco B, Erclik T, Shy D, Sclafani J, Lipshitz H, McInnes R, Hartenstein V. Specification and development of the pars intercerebralis and pars lateralis, neuroendocrine command centers in the Drosophila brain. Dev Biol. 2007;302:309–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar B. How flies get their size: genetics meets physiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:907–916. doi: 10.1038/nrg1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldon ED, Pirrotta V. Interactions of the Drosophila gap gene giant with maternal and zygotic pattern-forming genes. Development. 1991;111:367–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen JP, Wieschaus EF. The localized requirements for a gene affecting segmentation in Drosophila: analysis of larvae mosaic for runt. Dev Biol. 1985;109:321–35. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Rybczynski R, Warren JT. Control and biochemical nature of the ecdysteroidogenic pathway. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:883–916. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques G. Retrograde Gbb signaling through the Bmp type 2 receptor Wishful Thinking regulates systemic FMRFa expression in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:5457–5470. doi: 10.1242/dev.00772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer Z, Ono H, Shimell M, Parvy J, Beckstead R, Warren J, Thummel C, Dauphinvillemant C, Gilbert L, Oconnor M. Prothoracicotropic Hormone Regulates Developmental Timing and Body Size in Drosophila. Developmental Cell. 2007;13:857–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EW, Chang F, Lehmann B, Terrian DM, Milella M, Tafuri A, Stivala F, Libra M, Basecke J, Evangelisti C, Martelli AM, Franklin RA. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menut L, Vaccari T, Dionne H, Hill J, Wu G, Bilder D. A mosaic genetic screen for Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressor genes based on defective pupation. Genetics. 2007;177:1667–77. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.078360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirth CK, Riddiford LM. Size assessment and growth control: how adult size is determined in insects. Bioessays. 2007;29:344–55. doi: 10.1002/bies.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler J, Eldon ED, Pirrotta V. A novel spatial transcription pattern associated with the segmentation gene, giant, of Drosophila. Embo J. 1989;8:1539–48. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF. The control of body size in insects. Dev Biol. 2003;261:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petschek JP, Perrimon N, Mahowald AP. Region-specific defects in l(1)giant embryos of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1987;119:175–89. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinitz J, Levine M. Control of the initiation of homeotic gene expression by the gap genes giant and tailless in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1990;140:57–72. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90053-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz KF, Yamanaka N, Gilbert LI, O’Connor MB. The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science. 2009;326:1403–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1176450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybczynski R, Gilbert LI. Changes in general and specific protein synthesis that accompany ecdysteroid synthesis in stimulated prothoracic glands of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;24:175–89. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MB, Imberski RB, Kelly TJ. Analysis of metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster: characterization of giant, an ecdysteroid-deficient mutant. Dev Biol. 1984;103:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigmund T, Korge G. Innervation of the ring gland of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:481–91. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010319)431:4<481::aid-cne1084>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic D, Small S, Levine M. Regulation of a segmentation stripe by overlapping activators and repressors in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 1991;254:1385–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1683715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi-Hartenstein A, Green P, Liaw GJ, Rudolph K, Lengyel J, Hartenstein V. Control of early neurogenesis of the Drosophila brain by the head gap genes tll, otd, ems, and btd. Dev Biol. 1997;182:270–83. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]