Abstract

White-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) serve as the principal reservoir for Borrelia burgdorferi and have been shown to remain infected for life. Complex infections with multiple genetic variants of B. burgdorferi occur in mice through multiple exposures to infected ticks or through exposure to ticks infected with multiple variants of B. burgdorferi. Using a combination of cloning and single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP), B. burgdorferi ospC variation was assessed in serial samples collected from individual P. leucopus during a single transmission season. In individuals with ospC variation, at least seven ospC variants were recognized at each time point. One to four of these variants predominated at each time point; however, the predominant variants seldom remained consistent in an individual mouse throughout the entire sampling period. These results confirmed that mice in southern Maryland were persistently infected with multiple variants of B. burgdorferi throughout the transmission season. However, the presence of multiple ospC variants and the fluctuations in the frequency of these variants indicates that either new ospC variants are regularly introduced to this mouse population and predominate while the existing infections are cleared, or that the variation detected in the genetic profile at different time points reflects a complex mixture of B. burgdorferi populations whose relative frequencies may continually change. Key Words: Borrelia—Ixodes—Lyme disease.

Introduction

Peromyscus leucopus, the white-footed mouse, serves as a host for larval and nymphal Ixodes scapularis, the vector of Borrelia burgdorferi and etiologic agent of Lyme disease in eastern North America. Peromyscus leucopus and other rodents remain infected for 1 year or longer when infected with B. burgdorferi, making them extremely successful reservoirs for continuing the enzootic cycle of this bacterium (Johnson et al. 1984, Duray and Johnson 1986, Donahue et al. 1987, Barthold et al. 1993, Hofmeister et al. 1999). In field studies, B. burgdorferi is detected throughout the year in P. leucopus, with the highest prevalence (∼75%) occurring between June and August (Anderson et al. 1987). In mice with existing infections, new infections can be introduced through subsequent tick bites (Bunikis et al. 2004).

Recent studies concluded that B. burgdorferi persistence is related to pathogen diversity (Hefty et al. 2002). Borrelia burgdorferi from mixed strain infections in mice can be successfully transferred to xenodiagnostic ticks. However, in almost all cases, only one strain is detected in the tick, suggesting that interference exists between the experimental infecting strains (Derdakova et al. 2004). Elias et al. (2002) hypothesized that in vitro growth of clonal B. burgdorferi strains may result in a heterogeneous population due to instabilities in the genome under the in vitro conditions.

The outer surface protein C (ospC) gene is frequently analyzed as a marker of infection but is of additional interest due to the high levels of diversity at both global and local scales (Wang et al. 1999). OspC is a highly polymorphic gene with 22 recognized groups where differentiation is defined by less than 2% sequence divergence within and greater than 8% sequence divergence between groups (Seinost et al. 1999, Wang et al. 1999). Between samples, the amino acid sequence identity of ospC is only 70–74% (Jauris-Heipke et al. 1993), with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolated in the United States being more heterogeneous than European isolates, suggesting that B. burgdorferi s.s. originated in the United States (Marti Ras et al. 1997).

Pathogenicity and degree of invasiveness have been associated with certain ospC groups (Seinost et al. 1999, Lagal et al. 2003). However, Lagal et al. (2003) determined that the clinical presentation of Lyme disease cannot be reliably predicted by the ospC sequence. In C3H mice, the severity and dissemination of B. burgdorferi depends on the isolate used for the infection which is not necessarily associated with the ospC sequence (Wang et al. 2001, 2002). Based on ospC sequences and original isolate source, Seinost et al. (1999) suggested three categories for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto: (1) isolates not from humans, (2) isolates from erythema migrans in humans, and (3) isolates from disseminated infections in humans, with this last group considered as the invasive group. Recent studies indicated that these groupings may not be accurate since two-thirds of human isolates in the mid-Atlantic region did not cluster with these invasive groups when sequenced (Alghaferi et al. 2005).

Multiple B. burgdorferi strains can exist in an individual mouse or tick at a given time point (Hofmeister et al. 1999, Wang et al. 1999). In mice experimentally infected with a mixture of B. burgdorferi clones, the relative dominance of the clones shifts during infection (Hofmeister et al. 1999). The mechanism behind this variance is not understood, but in some individuals, only one clone from the original heterogeneous mixture was detected at different time points, suggesting that competition or immune pressure from the host may be involved in selection of the dominant clones.

Previous cross-sectional studies in our laboratory have confirmed high diversity in ospC among rodent samples collected in southern Maryland, but the maintenance of this diversity within individuals throughout a transmission season had not been explored. The current study investigated whether the ospC variation observed in samples was attributable to the presence of multiple B. burgdorferi variants at each time point. We hypothesized that the observed ospC variant changes could be the result of a persistent infection complicated by the introduction of new variants, the resolution of the original infection and the subsequent introduction of new infectious variants, or the fluctuation in the relative frequency of individual variants in a complex infection.

Methods

Sample collection and extraction

Peromyscus leucopus were trapped once a month from May through October 2002 in southern Maryland. One hundred Sherman traps (H.B. Sherman Traps, Tallahassee, FL) were placed in a 50 m × 200 m grid for 3 consecutive nights each month. At the time of first capture for each trapping period, ear tissue punch biopsies (2 mm) were collected. Tissue samples were extracted using the QIAamp DNA MiniKit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol with a single modification. After step 3 of the Tissue Protocol, samples were centrifuged for 3.5 min at 13,000 rpm to pellet the undigested hair, continued at step 4 using the supernatant, and eluted in 50 μL of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) water.

PCR-based pathogen detection

Samples were obtained from mice that were sampled at least twice and were positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for B. burgdorferi ospC, following the protocol of Wang et al. (1999) with modifications. The protocol was modified to use 1.5 μL (∼22 ng) of template DNA for the first round of PCR, and the annealing temperature was increased from 54°C to 60°C for the second round of PCR.

Cold single strand conformation polymorphism

Single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) was performed twice to analyze the genetic diversity of ospC (Orita et al. 1989, Norris et al. 1999). The first round was to determine whether the ospC fragment variation changed between sampling times in an individual mouse. The second round was performed after cloning amplicons from individuals whose ospC banding pattern varied at different time points in the first SSCP. For each positive clone, 5 μL of PCR product was added to 7 μL of denaturing loading mix (90% deionized formamide, 2% 1M NaOH, 8% ddH2O, 0.005 g xylene cyanol, 0.005 g bromophenol blue) and heated to 95°C for 7 min before snap annealing on ice. A 10-μL volume of each mixture was loaded on a nondenaturing 38.5% polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed at 4°C at constant 25 mA for approximately 3 h on a vertical gel unit (16 × 18 cm, SE600 series; Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA). Gels were stained using SYBR Green I Nucleic Acid Stain (Cambrex Bio-Science, Rockland, ME) and photodocumented.

Cloning and data analysis

ospC samples from four individuals with varying banding patterns and from two individuals with constant banding patterns were cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). The ospC amplicon vector fusion was transformed into OneShot TOP10 chemically competent Escherichia coli cells. A minimum of 94 transformed colonies were selected and screened by PCR using the ospC inner forward and outer reverse primers. For PCR, 1 μL of the sample diluted in 50 μL HPLC water was used as template. A minimum of 72 of the randomly selected 94 transformed clones from each original sample were used for analysis using SSCP. Banding patterns observed on SSCP gels were analyzed for differences within an individual. The number of different variants and changes in the frequency of those variants in individual mice were examined over the sampling period.

Results

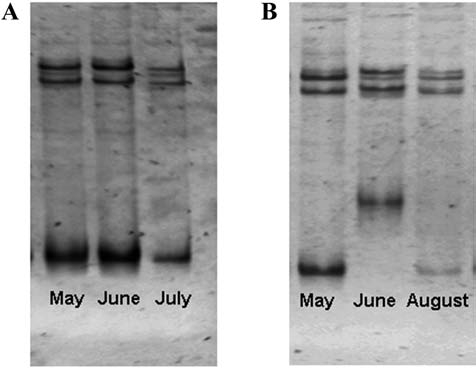

Tissue samples were collected from 59 P. leucopus captured during two or more trapping periods. Of these, 28 (48%) were positive for B. burgdorferi infection by ospC PCR during at least two sampling periods. ospC diversity was analyzed using SSCP for 26 individuals; two individuals were not completed due to poor PCR results. The SSCP banding patterns for 18 individuals (18/26; 69%) remained the same at all sampling times (Fig. 1A). When samples from individuals with consistent banding patterns were cloned and examined using SSCP, the banding patterns were identical in all clones from a single sample and between all samples from that individual, confirming that only one ospC variant was present in each of these individuals. Banding patterns that differed at subsequent time points were observed in 31% (8/26) of individuals (Fig. 1B). Each of these individuals was captured and sampled between two and five times during the 6-month trapping period. High ospC diversity was observed on SSCP within any single sample from individuals with changing banding patterns (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) gels illustrating banding patterns of ospC-positive P. leucopus that were sampled in multiple months. (A) SSCP gel illustrating conserved banding pattern across time points for a single animal. (B) SSCP gel illustrating variable banding patterns across time points for a single animal.

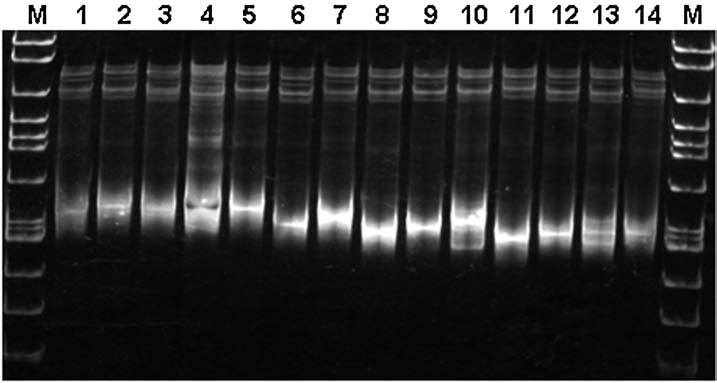

FIG. 2.

Single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) gel showing 11 ospC variants recovered by cloning of a single polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicon (2002072311) from an individual P. leucopus (Mouse 005). Identical banding patterns are in lanes 2 and 5; lanes 6 and 9; and lanes 8 and 12. The molecular marker (M) is used as a guide for identifying banding patterns and not as a size indicator.

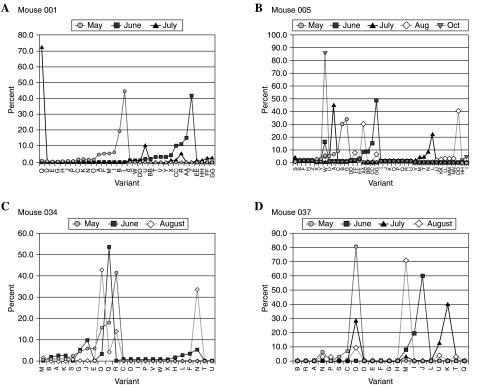

In a subset of four individuals whose ospC banding pattern changed over time, SSCP analysis revealed 21–41 ospC variants per individual. At any time point, however, the number of variants observed in an individual was 7–19 (Fig. 3). The majority of these variants represented less than 10% of the clones analyzed in a single sample; variants that were present in more than 10% of the clones analyzed were considered to be predominant. In any one individual, the total number of predominant variants from all samples analyzed was 7–9 (Table 1), with one to four variants predominating (frequencies of 10–87%) at each time point (Table 2). The relative dominance of the ospC variants present in an individual mouse shifted in serial samples, often appearing at a much lower frequency or not detectable at all. Conversely, a variant detected at a low frequency in 1 month could be present in the majority of the clones analyzed from a sample collected in a later month. In addition, variants that were not detected at all during one sampling period could be detected in a majority of clones in another sample from that same individual. Due to the nature of this study and the large number of SSCP variants observed, variation was quantified based on banding patterns rather than on sequence data.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of ospC variants identified in individual P. leucopus each month. The letter designations for each variant are valid within each individual only. They do not correspond between individuals.

Table 1.

ospC Variants Observed for a Subset of Individual P. leucopus When the ospC PCR Product was Cloned and Analyzed by SSCP

| Mouse | Number of samples cloned | Total number of variants identified | Total number of predominant variants* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 3 | 34 | 8 |

| 005 | 5 | 41 | 9 |

| 034 | 3 | 24 | 7 |

| 037 | 4 | 21 | 8 |

Predominant variants are those occurring in more than 10% of clones analyzed.

Table 2.

ospC Variant Frequencies for a Subset of Individual P. leucopus by Month

| Mouse | Month | Number of clones analyzed by SSCP | Number of variants present | Number of predominant variants* | Range of variant frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | May | 109 | 17 | 2 | 1–45 |

| June | 98 | 14 | 4 | 1–42 | |

| July | 72 | 9 | 2 | 1–72 | |

| 005 | May | 80 | 13 | 2 | 1–34 |

| June | 88 | 8 | 3 | 1–49 | |

| July | 73 | 15 | 2 | 1–45 | |

| August | 82 | 11 | 2 | 1–40 | |

| October | 89 | 7 | 1 | 1–87 | |

| 034 | May | 82 | 11 | 3 | 1–42 |

| June | 111 | 19 | 1 | 1–53 | |

| August | 98 | 8 | 3 | 1–43 | |

| 037 | May | 91 | 8 | 1 | 1–80 |

| June | 87 | 10 | 2 | 1–60 | |

| July | 85 | 10 | 3 | 1–40 | |

| August | 89 | 9 | 2 | 1–71 |

Predominant variants are those occurring in more than 10% of clones analyzed.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to determine whether the ospC changes observed by SSCP in serial samples from individual mice were the result of concurrent infections with multiple variants of B. burgdorferi or whether they were evidence of successive infection with different ospC variants. This study is the first to our knowledge to examine the temporal genetic variation of B. burgdorferi within individuals by intensively studying serial samples from mice. The small sample size (n = 4) limits the conclusions that can be made regarding B. burgdorferi infections in all P. leucopus populations. However, a wide number of ospC variants were present in an individual mouse at different time points. Furthermore, some variants appeared in or disappeared from the individual at different time points. In all of the individuals displaying ospC variation, minor variants were always present with the major or predominant variants.

This study investigated the number of B. burgdorferi ospC variations detected within persistently infected individual P. leucopus and whether the frequency of those variants changed or remained constant during a transmission season. Although nearly 70% of the individuals appeared to maintain an infection with a single ospC variant, the remainder displayed infections of a far more complex nature. This second group of mice displayed concurrent infection with more than one ospC type as evidenced by the SSCP banding patterns that changed from sample to sample. The changes observed in the SSCP banding patterns in these individuals were hypothesized to be due to fluctuations within complex infections of multiple ospC variants or due to the introduction of new infections with different variants. Our results show that different situations can coexist in an individual mouse: some ospC variants were detected repeatedly over the span of months, but at varying levels; other variants completely disappeared from subsequent samples; still other variants appeared for the first time several months after the study began, possibly indicating the introduction of a new infection. In order to fully understand the implications of this study, all variants need to be sequenced. Sequence data would confirm whether or not the differences seen in ospC variants in these serial samples are sufficiently divergent (>8%) to be considered different variants and would allow comparison of the variants to the current ospC groups.

The immune response to B. burgdorferi in P. leucopus prevents re-infection with the same ospC variant as the original infecting variant but does not prevent infection with spirochetes carrying other ospC groups through subsequent exposures (Preac-Mursic et al. 1992, Probert et al. 1997). Multiple variants of ospC are known to infect at least 30% of P. leucopus in southern Maryland, with 25% of the mice infected with at least three different ospC groups simultaneously (Anderson and Norris 2006). Based on SSCP, approximately 31% of P. leucopus in our study were infected with multiple variants of ospC, confirming the point prevalence findings of Anderson and Norris (2006). Experimentally, infection with two strains of ospC can be maintained as subpopulations which persist in the mouse and then re-emerge at a later time (Hofmeister et al. 1999, Derdakova et al. 2004). In our study of naturally infected P. leucopus, a variant that was clearly prevalent in an individual and became either less common or undetectable at later points in time suggests that the variant was being maintained below a detectable level, that the variant had been completely eliminated from the mouse, or that the variant had possibly undergone genetic modifications of ospC. Intensive study of the ospC variants in four mice showed that the most frequent variant in a mouse remained so only during one sampling time point. Although the variant may have been present in earlier or later samples, it was never again the most prevalent variant in that individual. This indicates that the mouse's immune system may be able to control the infection, thereby preventing it from becoming the most prevalent variant again, even though it may remain in circulation as a minor variant. This would allow other ospC variants to become established as the most abundant variants at other time points.

This study demonstrates that enormous variability exists in ospC isolates, within a small sample size from a small geographic region. The number of ospC variants observed in each mouse at any single time point differed widely, ranging from 7 to 19 at a single time point in an individual mouse. Of the 22 recognized variants of ospC, eight have been identified in Maryland and confirmed through sequencing and phylogenetic analysis (Anderson and Norris 2006). In P. leucopus in southern Maryland, two ospC groups (identified as A and K) occurred in 68% of the samples from a cross-sectional study while two other groups (identified as C and D) were identified in less than 2% of the samples (Anderson and Norris 2006). An earlier study in Baltimore County, Maryland, identified ospC groups A and K in P. leucopus (Hofmeister et al. 1999). Due to the large number of ospC variants recognized in the current study, variants were not identified by sequencing, and, therefore, cannot be defined as belonging to specific ospC groups. However, the number of SSCP variants seen in this study suggest that genetic sequencing of serially collected samples would allow comparison with the findings of these other two studies, and would allow the determination of patterns of predominance of specific ospC groups in individuals showing complex infections with B. burgdorferi. The subtle differences observed in the SSCP banding patterns in our serial samples may represent point mutations. Sequencing results from a previous study identified 127 point mutations among ospC amplicons recovered from P. leucopus and I. scapularis (Anderson and Norris 2006). If all variants in this study were sequenced, the number of variants per sample may be reduced since variants with less than 2% difference between each other would be included in the same group. Alternatively, the ospC variation observed in individuals between time points could also be due to PCR bias for the most prevalent variant in the sample. Bias for certain genotypes has also been demonstrated through the PCR amplification of wild-type and mutant ospA at different frequencies (Malawista et al. 2000). Patterns of bias towards amplification of specific variants, however, were not noted which diminishes this possibility in our dataset.

We have corroborated the laboratory-based experiments of Hofmeister et al. (1999) showing that, in some individual mice, a single clonal population of B. burgdorferi appears to be maintained in a persistent infection. However, we found that, in other P. leucopus, the state of persistent infection was a result of the presence of multiple variants of B. burgdorferi and that the relative frequency of each variant was different at subsequent time points. Fluctuations in the frequency of ospC variants indicates that either new variants are regularly introduced to the mice while the existing infections are minimized or cleared, creating a changing pattern of predominance, or that the B. burgdorferi genetic profile constantly fluctuates in these mice as a result of dynamic spirochete populations. The maintenance of mixed infections of B. burgdorferi in naturally infected P. leucopus is hypothesized to be common (Hofmeister et al. 1999).

The high levels of variability present in individual mouse reservoirs may affect the diversity of variants transmitted to humans via ticks. Therefore, since certain ospC groups may be more infective to humans, the potential disease risk to humans depends on which ospC groups are circulating in the reservoir population. This study demonstrated that not all variants present in this reservoir population can be detected without cloning and that the presence and frequency of variants changes on a temporal scale. Therefore, without the benefit of cloning the samples, the presence of infective variants may go unrecognized.

The extensive ospC variation found in individual mice reinforces the need to fully understand the dynamics of ospC infections in the reservoirs since the vectors can presumably acquire any of these different ospC variants and transmit them to humans. The proposed links between ospC genotype and degree of invasiveness in human disease (Seinost et al. 1999) and the recent findings which contradict this association (Alghaferi et al. 2005) underscore the importance of understanding the complexity of the variants of ospC that are infecting mice. However, recent studies indicate that plasmids lp25 and lp28-1, rather than plasmid cp26 (which contains ospC), are important for infectivity and, in the case of lp28-1, persistence of B. burgdorferi in mammals (Purser and Norris 2000, Labandeira-Rey et al. 2001, 2003). Both of these plasmids encode for virulence factors which may be more important and relevant than ospC when studying B. burgdorferi pathogenesis. Therefore, studies examining these plasmids and the diversity of genes located on them in naturally infected P. leucopus will be useful in future genetic studies of B. burgdorferi.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Training Fellowship (T32ES07141, to K.I.S.) and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement (U50/CCU319554, to D.E.N.).

Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- Alghaferi MY. Anderson JM. Park J. Auwaerter PG, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi ospC heterogeneity among human and murine isolates from a defined region of northern Maryland and southern Pennsylvania: lack of correlation with invasive and noninvasive genotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1879–1884. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1879-1884.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM. Norris DE. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in Peromyseus leucopus, the primary reservoir of Lyme disease in a region of endemicity in Southern Maryland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5331–5341. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00014-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JF. Johnson RC. Magnarelli LA. Seasonal prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in natural populations of white-footed mice, Peromyscus leucopus. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1564–1566. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.8.1564-1566.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW. de Souza MS. Janotka JL. Smith AL, et al. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:959–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunikis J. Tsao J. Luke CJ. Luna MG, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi infection in a natural population of Peromyscus leucopus mice: a longitudinal study in an area where Lyme borreliosis is highly endemic. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1515–1523. doi: 10.1086/382594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdakova M. Dudioak V. Brei B. Brownstein JS, et al. Interaction and transmission of two Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strains in a tick-rodent maintenance system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6783–6788. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6783-6788.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue JG. Piesman J. Spielman A. Reservoir competence of white-footed mice for Lyme disease spirochetes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36:92–96. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duray PH. Johnson RC. The histopathology of experimentally infected hamsters with the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986;181:263–269. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias AF. Stewart PE. Grimm D. Caimano MJ, et al. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2139–2150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2139-2150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefty PS. Jolliff SE. Caimano MJ. Wikel SK, et al. Changes in temporal and spatial patterns of outer surface lipoprotein expression generate population heterogeneity and antigenic diversity in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3468–3478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3468-3478.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister EK. Glass GE. Childs JE. Persing DH. Population dynamics of a naturally occurring heterogeneous mixture of Borrelia burgdorferi clones. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5709–5716. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5709-5716.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauris-Heipke S. Fuchs R. Motz M. Preac-Mursic V, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of the genes coding for the outer surface protein C (ospC) and the flagellin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:37–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00195949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC. Marek N. Kodner C. Infection of Syrian hamsters with Lyme disease spirochetes. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1099–1101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1099-1101.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Rey M. Baker E. Skare J. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.446-455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Rey M. Seshu J. Skare JT. The absence of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi dramatically alters the kinetics of experimental infection via distinct mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4608–4613. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4608-4613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagal V. Postic D. Ruzic-Sabljic E. Baranton G. Genetic diversity among Borrelia strains determined by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of the ospC gene and its association with invasiveness. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5059–5065. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5059-5065.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista SE. Montgomery RR. Wang XM. Fu LL, et al. Geographic clustering of an outer surface protein A mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi. Possible implications of multiple variants for Lyme disease persistence. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:537–541. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti Ras N. Postic D. Foretz M. Baranton G. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, a bacterial species “made in the U.S.A.”? Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1112–1117. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE. Johnson BJB. Piesman J. Maupin GO, et al. Population genetics and phylogenetic analysis of Colorado Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:699–707. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita M. Iwahana H. Kanazawa H. Hayashi K, et al. Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preac-Mursic V. Wilske B. Patsouris E. Jauris S, et al. Active immunization with pC protein of Borrelia burgdorferi protects gerbils against B. burgdorferi infection. Infection. 1992;20:342–349. doi: 10.1007/BF01710681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert WS. Crawford M. Cadiz RB. LeFebvre RB. Immunization with outer surface protein (Osp) A, but not OspC, provides cross-protection of mice challenged with North American isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:400–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser JE. Norris SJ. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13865–13870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seinost G. Dykhuizen DE. Dattwyler RJ. Golde WT, et al. Four clones of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto cause invasive infections in humans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3518–3524. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3518-3524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Ojaimi C. Iyer R. Saksenberg V, et al. Impact of genotypic variation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto on kinetics of dissemination and severity of disease in C3H/HeJ mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4303–4312. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4303-4312.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Ojaimi C. Wu H. Saksenberg V, et al. Disease severity in a murine model of Lyme borreliosis is associated with the genotype of the infecting Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strain. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:782–791. doi: 10.1086/343043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I-N. Dykhuizen DE. Qiu W. Dunn JJ, et al. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics. 1999;151:15–30. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]