Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between perceived discrimination and use of mental health services among a national sample of Asian Americans.

Methods. Our data came from the National Latino and Asian American Study, the first national survey of Asian Americans. Our sample included 600 Chinese, 508 Filipinos, 520 Vietnamese, and 467 other Asians (n=2095). We used logistic regression to examine the association between discrimination and formal and informal service use and the interactive effect of discrimination and English language proficiency.

Results. Perceived discrimination was associated with more use of informal services, but not with less use of formal services. Additionally, higher levels of perceived discrimination combined with lower English proficiency were associated with more use of informal services.

Conclusions. The effect of perceived discrimination and language proficiency on service use indicates a need for more bilingual services and more collaborations between formal service systems and community resources.

Asian Americans are one of the fastest-growing racial groups in the United States and also one of the most understudied.1 Recent data from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), the first national study of Asian Americans, show that they have a sizeable burden of mental illness, with a 17.30% overall lifetime rate of any psychiatric disorder and a 9.19% 12-month rate.2 At the same time, low utilization rates of mental health services by Asian Americans are well documented.3–7 Nationally, Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders are one third as likely as Whites to use available mental health services.3 Low use rates have been reported for emergency and inpatient services4–6 as well as outpatient services.4,7,8

In the United States over a 12-month period, only 3.1% of Asian Americans use specialty mental health services, compared with 5.59% of African Americans, 5.94% of Caribbean Blacks, 4.44% of Mexicans, 5.55% of Cubans, and 8.8% of the general population.9–11 In a study by Abe-Kim et al., only 8.6% of Asian Americans sought any mental health services compared with 17.9% of the general population.12 Kimerling and Baumrind found that Asian American women were less likely than White women to report perceived need for mental health services, even when accounting for frequency of mental distress. Among women who did perceive a need to seek mental health services, Asian American women were less likely to use services even when health insurance was controlled.13

Despite low use rates for formal services, research has established that Asian Americans are more likely to use informal support systems for help with mental health issues as to use formal services. Data from the Chinese American Epidemiology Study (CAPES) found that of Chinese Americans experiencing mental health problems in the past 6 months, fewer than 6% saw mental health professionals, 4% saw medical doctors, and 8% saw a minister or priest.14 A study using data from the Filipino American Community Epidemiological Study (FACES) found that of the 25% of Filipino Americans who used any type of care in the past 12 months, 17% went to the lay system (a friend or relative), 7% used medical doctors, 4% saw a clergy member or indigenous healer, and only 3% saw a mental health specialist.15 In a study using data from the CAPES, negative attitudes toward formal mental health services were correlated with more informal service use.16

Discrimination is a major stressor experienced by American ethnic groups.17 Experiences with discrimination shape one's appraisal of the world and hinder the ability to control one's environment, thus reinforcing secondary social status and internalizing negative stereotypes.18–20 There are many well-documented examples of policies and practices that have systematically discriminated against Asian Americans throughout US history.21,22 Contemporary forms of discrimination include the model minority stereotype (which highlights the aggregation of success indicators while masking the challenges of immigrant populations), hate crimes, racial profiling, and employment discrimination.23–28 Increasingly, researchers have demonstrated an association between racial discrimination and mental disorders among Asian Americans.29–38

Discrimination also may be a barrier to help seeking among Asian Americans. Indeed, research has found that perceived discrimination is significantly correlated with underuse of mental health care among Asian Americans.39 Further, it is possible that discrimination may interact with other barriers to treatment. For example, Spencer and Chen found that discrimination based on speaking a different language or speaking with an accent was associated with use of more informal services among Chinese Americans.16 Uba cites racial and cultural biases—such as culturally inappropriate services, differential receipt of services, a history of institutional discrimination, and a suspicion of the service delivery system—as critical barriers to service use for Asian Americans.40

Other immigrant-related factors are important correlates of service use. For example, rates of use were found to vary by generation: US-born, third-generation or later Asian Americans had higher rates of use of specialty mental health services than did first- or second-generation individuals.12 Other studies that have examined correlates of service use among Asian Americans have identified cultural factors, such as shame and loss of face41–44; lack of ethnic match between provider and client, bilingual providers, knowledge of available services, and insurance coverage; socioeconomic factors; and neighborhood poverty.12,25,45–49 Language is a particularly important correlate of service use for Asian Americans: those who have poor English skills may be less likely to use mental health services. For example, a study of East Asian immigrants found that English fluency was positively related to willingness to use psychological services.50

We examined the association between perceived discrimination and service use, controlling for demographic characteristics, poverty status, immigration status, and barriers to services related to access and attitudes, in a national representative sample of Asian Americans using data from the NLAAS. Specifically, we examined rates of formal and informal service use. We hypothesized that discrimination would be associated with less use of formal services and more use of informal services. We also hypothesized that individuals with low English proficiency in addition to higher rates of self-reported discrimination would be less likely to use formal services and more likely to use informal services for mental health problems.

METHODS

Data for this study come from the NLAAS, a household survey conducted between May 2002 and November 2003. The current analyses include only the sample of Asian Americans. The sampling procedure included 3 components: (1) core sampling of primary sampling units (metropolitan statistical areas and counties) and secondary sampling units (from continuous groupings of census blocks) using probability sampling according to the size of the census block, from which housing units and household members were sampled; (2) high-density supplemental sampling of census block groups with a density of targeted ethnic groups of greater than 5%; and (3) second-respondent sampling to recruit participants from households where a primary respondent had already been interviewed. Survey weights were developed to take into account the joint probabilities of selection for these 3 components and to allow the sample estimates to be nationally representative. Details of the complex sample design are found in Heeringa et al.51

A total of 2095 Asian American adults were interviewed in either English, Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin), Tagalog, or Vietnamese by trained bilingual interviewers, who used computer-assisted interviewing software. Further details of the study procedures and field implementation have been previously documented.51–53 Our sample included 600 Chinese, 508 Filipinos, 520 Vietnamese, and 467 other Asians (Table 1). The 467 other Asians comprised 107 Japanese, 141 Asian Indians, 81 Koreans, 39 Pacific Islanders, and 99 members of other small subgroups.

TABLE 1.

Individual Characteristics of Asian Americans and Their Use of Mental Health Services: National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002–2003

| Characteristic | No. (%) or Mean (SD) |

| 12-month use of mental health services | |

| Use of any formal mental health service | 83 (3.70) |

| Use of any informal mental health service | 60 (2.91) |

| Use of any mental health-related service | 179 (8.56) |

| Mental and physical health status | |

| Any 12-month psychiatric disorder | 192 (9.46) |

| Chronic illnesses (range = 0–10) | 1.34 (1.45) |

| Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination (1 = low, 4 = high) | 1.72 (0.69) |

| English proficiency good or excellent | 1292 (66.19) |

| Barriers to service use | |

| No health insurance | 290 (13.16) |

| Embarrassment (1 = low, 4 = high) | 2.12 (0.98) |

| Generational status | |

| Foreign-born, first-generation immigrant | 1369 (76.94) |

| US-born, second generation | 272 (13.68) |

| US-born, third generation | 182 (9.38) |

| In poverty | 357 (17.55) |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age, y | 41.33 (15.61) |

| Female | 998 (52.55) |

| Married | 1376 (65.39) |

| Ethnic group | |

| Chinese | 600 (28.69) |

| Filipino | 508 (21.59) |

| Vietnamese | 520 (12.93) |

| Other Asian | 467 (36.79) |

Note. Analyses are weighted to be nationally representative; survey design effects are taken into account.

Measures

Mental health–related service use.

Mental health–related service use was assessed with the question, “In the past 12 months, did you go to see [provider on list] for problems with your emotions, nerves, or your use of alcohol or drugs?” We classified the 13 services on the list into 3 categories: (1) formal service (psychiatrist; psychologist; social worker; counselor; any other mental health professionals, such as a psychotherapist or mental health nurse), (2) informal service (a religious or spiritual advisor such as a minister, priest, pastor, or rabbi; any other healer, such as an herbalist, doctor of oriental medicine, chiropractor, or spiritualist; hotline; Internet support group or chat room; self-help group), and (3) general health service (general practitioner or family doctor; any other medical doctor; nurse, occupational therapist, or other health professional).

Three dichotomous variables were computed: use of formal service (1 = at least 1 formal service; 0 = none), informal service (1 = at least 1 informal service; 0 = none), and use of any service (1 = at least 1 of the listed services; 0 = none). We used 12-month service use rather than lifetime service use to limit the threats of recall bias and temporal ordering of causal factors. Our categories are similar to those used in a study of service use by Abe-Kim et al. that also used the NLAAS.12 We used these categories to distinguish the effects of discrimination on Asian Americans’ use of specialty mental health services (formal service delivery systems) compared with their use of other possible sources of help (informal systems). Users of general health services include those who speak to their health care provider about mental health issues.

Mental and physical health status.

The following 4 categories of 12-month psychiatric disorders were dichotomous variables indicating the presence or absence of a disorder within the past 12 months: (1) depressive disorders (major depressive disorder or dysthymia), (2) anxiety disorders (panic attack, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder), (3) substance disorders (alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, or drug dependence), or (4) eating disorders (anorexia or bulimia). This variable was assessed with the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI).54

Chronic illness was assessed by the WMH-CIDI checklist of the following 10 lifetime physical problems: arthritis or rheumatism, chronic back or neck problems, frequent or severe headaches, stroke, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma, tuberculosis, diabetes or high blood sugar, and cancer.54 The sum of these items ranged from 1 to 10. Mental and physical health statuses are often correlated with service use on the basis of need for services, above and beyond attitudes and experiences with discrimination, and were therefore included in this study as covariates. For example, Wang et al. found in the National Comorbidity Study that 41.1% of individuals in the general population with any psychiatric disorder used some form of mental health services, compared with 10.1% that did not report a disorder.9

Discrimination.

Perceived discrimination was assessed by 3 questions: (1) “How often do people dislike you because of your race/ethnicity?” (2) “How often do people treat you unfairly because of your race/ethnicity?” and (3) “How often have you seen friends treated unfairly because of their race/ethnicity?” Responses to these questions were summed and averaged; the range was 1 = never to 4 = often (α = 0.86).

Language proficiency.

English language proficiency was assessed by the question, “How well do you speak English?” (1 = excellent or good; 0 = fair or poor).

Barriers to service use.

We computed 2 variables to measure barriers to service use. No health insurance was dichotomously coded, with 1 = respondent had “no health insurance” and 0 = respondent had some form of health insurance. Shame was assessed by the question, “How embarrassed would you be if your friends knew you were getting professional help for an emotional problem?” The scale ranged from 1 = not at all embarrassed to 4 = very embarrassed.

Other variables we assessed included the following: generational status comprised 3 categories (0 = foreign-born, first-generation immigrant; 1 = US-born, second generation; 2 = US-born, third generation), similar to the categories used by Takeuchi et al.2; poverty status was a binary variable indicating whether the family income was beneath the federal poverty threshold for the corresponding family size in 2000; demographic characteristics included age in years, gender (1 = female; 0 = male), and marital status (1 = married; 0 = other).

Analyses

We computed weighted descriptive statistics so that the sample would be nationally representative. We used Stata version 9.2 SVY command (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) to adjust for complex survey design effects and to allow for estimation of standard errors in the presence of stratification and clustering. We used logistic regression to examine the association between perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health service use and the interactive effect of discrimination and English language proficiency. Our first set of models focused on the association between perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and the 3 types of service use (formal, informal, and any mental health–related service). We controlled for 12-month psychiatric disorder, chronic illness, barriers to service use, English language proficiency, generational status, poverty status, and demographic characteristics. In our second set of models, we added the interaction of perceived discrimination and English language proficiency. We computed interaction terms for discrimination × English proficiency. In preliminary analyses, we found that the coefficient for language proficiency did not differ significantly when discrimination was not included in the model. Also, the correlation between discrimination and language proficiency was quite low (−0.005); therefore, we tested only the moderating effects of these variables to examine whether the amount of discrimination reported depended on the level of English proficiency. We used α = 0.05 as our level of statistical significance; all confidence intervals and odds ratios are reported at 95%. We estimated the predicted probabilities of service use by holding all other control variables at their survey means.

RESULTS

Overall, levels of psychiatric disorders were comparable to those in other studies of Asian Americans, with 9.5% reporting any disorder. A mean of 1.72 was reported for our measure of perceived discrimination, indicating that respondents experienced moderate levels of discrimination. About 13% reported having no health insurance and modest levels of embarrassment about seeking services (mean embarassment = 2.1; SD = 0.98). About 8.6% indicated that they sought any mental health–related services in the past 12 months, including 3.7% seeking formal services and 2.9% seeking informal services.

Table 2 reports the results of our logistic regression analyses for factors related to use of mental health services during a 12-month period. Third-generation Asian Americans were twice as likely to use any services and more than 3 times as likely to use formal services as were first-generation individuals. Second-generation status was associated with a lower likelihood of use of informal services than first-generation status. Ethnicity was not associated with differences in formal, informal, or any service use, therefore we did not conduct further analyses by ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Regression Results of Factors Related to Use of Mental Health Services Among Asian Americans During a 12-Month Period: National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002–2003

| Use of Any Formal Mental Health Service |

Use of Any Informal Mental Health Service |

Use of Any Mental Health–Related Service |

||||

| Model I-1, OR (95% CI) | Model I-2, OR (95% CI) | Model II-1, OR (95% CI) | Model II-2, OR (95% CI) | Model III-1, OR (95% CI) | Model III-2, OR (95% CI) | |

| Mental and physical health status | ||||||

| Any 12-month psychiatric disorder | 7.55*** (3.82, 14.94) | 7.36*** (3.66, 14.79) | 6.75*** (3.06, 14.91) | 6.62*** (2.96, 14.83) | 5.58*** (3.58, 8.71) | 5.51*** (3.48, 8.72) |

| Chronic illness | 1.45*** (1.24, 1.71) | 1.45*** (1.23, 1.71) | 1.19*(0.98, 1.43) | 1.18*(0.98, 1.43) | 1.46*** (1.30, 1.65) | 1.46*** (1.30, 1.65) |

| Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination | 1.29 (0.74, 2.26) | 1.80 (0.78, 4.18) | 1.51** (1.10, 2.09) | 2.35*** (1.35, 4.10) | 1.26* (0.97, 1.64) | 1.46 (0.87, 2.46) |

| English proficiency good or excellent | 1.87 (0.82, 4.23) | 5.07* (0.87, 29.60) | 1.23 (0.36, 4.22) | 4.62*** (1.53, 13.95) | 1.31 (0.73, 2.38) | 2.07 (0.58, 7.33) |

| Perceived discrimination × English good or excellent | NAa | 0.61 (0.26, 1.41) | NA | 0.54 (0.28, 1.03) | NA | 0.79 (0.40, 1.56) |

| Barriers to service use | ||||||

| No health insurance | 1.49 (0.82, 2.70) | 1.41 (0.77, 2.58) | 2.41** (1.18, 4.94) | 2.36** (1.15, 4.87) | 1.26 (0.74, 2.13) | 1.24 (0.74, 2.07) |

| Embarrassment | 0.74 (0.49, 1.13) | 0.74 (0.48, 1.14) | 0.76 (0.46, 1.26) | 0.76 (0.46, 1.25) | 0.73** (0.56, 0.96) | 0.73** (0.56, 0.95) |

| Generational status | ||||||

| First-generation immigrant (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| US-born, second generation | 1.18 (0.38, 3.69) | 1.18 (0.39, 3.60) | 0.42** (0.18, 0.97) | 0.42** (0.18, 0.97) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.49) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.46) |

| US-born, third generation | 3.35*** (1.94, 5.80) | 3.26*** (1.89, 5.60) | 2.41* (0.98, 5.91) | 2.32* (0.94, 5.71) | 2.09** (1.02, 4.28) | 2.06** (1.00, 4.26) |

| In poverty | 1.32 (0.56, 3.13) | 1.28 (0.55, 3.00) | 0.46* (0.21, 1.05) | 0.44*(0.19, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.54, 1.59) | 0.93 (0.54, 1.59) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| Female | 1.26 (0.68, 2.35) | 1.31 (0.71, 2.44) | 2.41* (0.84, 6.90) | 2.52*(0.89, 7.17) | 1.47 (0.78, 2.76) | 1.49 (0.80, 2.76) |

| Married | 0.31*** (0.18, 0.55) | 0.32*** (0.18, 0.55) | 0.54 (0.20, 1.44) | 0.55 (0.21, 1.44) | 0.51*** (0.34, 0.76) | 0.51*** (0.34, 0.76) |

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| Chinese (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Filipino | 0.61 (0.28, 1.36) | 0.62 (0.29, 1.34) | 0.52 (0.23, 1.17) | 0.51* (0.23, 1.13) | 0.98 (0.56, 1.72) | 0.98 (0.56, 1.70) |

| Vietnamese | 1.49 (0.61, 3.64) | 1.52 (0.62, 3.77) | 0.62 (0.22, 1.76) | 0.61 (0.21, 1.79) | 1.77 (0.87, 3.62) | 1.81* (0.90, 3.64) |

| Other Asian | 0.68 (0.22, 2.12) | 0.67 (0.22, 2.06) | 0.82 (0.31, 2.17) | 0.79 (0.31, 2.00) | 1.22 (0.59, 2.54) | 1.22 (0.59, 2.50) |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable. Analyses are weighted to be nationally representative; survey design effects are taken into account. Models I-1, II-1, and III-1 include all variables in the model except discrimination. Models I-2, II-2, and III-2 include discrimination in the model.

In these models the interaction term was not included so that the main effects could be seen before the effect of the interaction term.

*P < .10; **P < .05, ***P < .01.

Asian Americans who experienced a psychiatric disorder in the past 12 months were 6.8 times more likely to use informal services and 7.6 times more likely to use formal services than were Asian Americans who did not experience a psychiatric disorder. Those who did not have health insurance were 2.4 times more likely to use informal services than were those who had insurance. Shame was associated with a lower likelihood of using any services. When we used other codings of the shame variable, including dichotomous and categorical values, the results were similar. The main effect of discrimination was a greater likelihood of using informal services. English proficiency was not associated with service use.

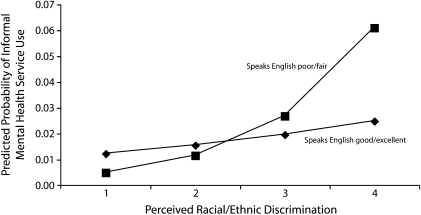

We examined the interaction between perceived discrimination and English proficiency. As shown in Figure 1, those with poor or fair English proficiency and a perception of higher levels of discrimination used informal services more than those with good or excellent English proficiency. Other interaction terms examined were not statistically significant.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted probability of use of informal mental health services among Asian Americans, by perceived discrimination and English proficiency: National Latino and Asian American Study, 2002–2003.

DISCUSSION

Our data from a national sample of Asian Americans indicate that perceived discrimination was associated with more use of informal services, as hypothesized. However, counter to our hypothesis, discrimination was not associated with less use of formal services. Further, language proficiency was not associated with any kind of service use. However, we also hypothesized that individuals who had less English proficiency and perceived more discrimination would be less likely to use formal services and more likely to use informal services. Our data show that higher levels of perceived discrimination in addition to lower English proficiency were associated with more use of informal services, but not with less use of formal services.

Studies of service use among Asian Americans suggest that utilization rates may be associated with the use of traditional healing methods.55 Although family and extended family often serve as an active support and source of help for psychological problems, the family may turn to outside help within their community, consulting indigenous healers and community elders for assistance when unable to resolve the problem.56,57 Delay of treatment that could have mitigated symptoms of mental health problems may occur as a result of seeking informal services when symptoms become severe and unmanageable, even if these informal supports are helpful.

The lack of association between perceived discrimination, English proficiency, and formal service use could be attributed to at least 2 factors. First, we could not examine causal relationships in this cross-sectional sample, and therefore it is possible that individuals experienced discrimination after using formal services. Second, it is possible that individuals with low English proficiency used ethnic-centered formal services or services tailored to Asian Americans (e.g., access to translators). We could not determine whether such formal services were used. More research is necessary to determine what factors draw Asian Americans to formal services despite their experiences with discrimination or lack of English proficiency.

In addition, our findings are consistent with previous research that highlights the significance of immigration-related factors.9,58 Specifically, compared with first-generation Asian Americans, the third generation used more formal services and the second generation used fewer informal services. Given these findings, culturally relevant services and outreach to these communities should be mindful of generational differences. Although empirically based Western interventions may be used by some second- and third-generation Asian Americans, cultural barriers may still be significant. Interestingly, first- and third-generation Asian Americans in our study were equally likely to use informal services, which indicates that collaboration between formal and informal service and support systems is warranted.

Increasingly, community health workers are being recognized as effective bridges between health care systems and minority communities,59–65 including Asian communities.66,67 Although community health workers are effective at helping minority populations to access physical health care, their promise for mental health access has yet to be fully explored. Another promising model in mental health services is the use of peer support, which often involves mutual support groups, consumer-run services, and the employment of consumers as providers within clinical settings.68 Community health workers and peer support specialists could mitigate negative attitudes related to discrimination, including discrimination based on language proficiency. More research must examine the implications of English proficiency, not only in terms of communication but of language bias in the form of English-only policies.

Our study also suggests that lack of health insurance is associated with more use of informal services and that embarrassment about seeking services is associated with less overall service use. Lack of health insurance is a common barrier to health care access among low-income racial and ethnic minorities.69 These findings are consistent with those of Spencer and Chen,16 who found that informal service use was higher among Chinese Americans without health insurance. Embarrassment about seeking services could also be related to traditional barriers such as stigma, but it might also be associated with cultural barriers such as fear of loss of face.41,43,70 Shame and loss of face are significant factors affecting service use because of the highly stigmatized nature of mental illness in many Asian cultures. Loss of face is a key interpersonal dynamic in Asian social relations that defines an individual's social integrity and the perception of the individual as an integral member of a group.70

Limitations

We did not conduct analyses stratified by ethnicity because the sample sizes were too small and because we did not detect significant differences in service use by ethnicity. However, we caution against using these findings to generalize to all Asian ethnic groups. Such monolithic approaches, although useful for calling attention to an understudied group as a whole, also obfuscate differential histories of immigration and adaptation among these ethnic groups.

Other limitations should be noted. First, it would have been informative to include a measure of language-based discrimination, but we did not have such a measure. Therefore, some of the interaction between discrimination and language proficiency may have resulted from language discrimination. Second, despite our use of a large, national sample of Asian Americans, the occurrence of mental health–related service use was quite low, which limited our statistical power to observe differences when they indeed existed. This also limited our ability to disaggregate our sample by ethnicity, gender, immigration status, or other significant factors that might have explained our findings more thoroughly. The NLAAS is a landmark study and will continue to yield new insights into the Asian American experience in the United States; however, it will likely also raise new questions that require further investigation.

Third, our study relied primarily on self-reported measures, including perceived discrimination. Our findings were based on a retrospective self-report of discrimination, which is susceptible to recall and reporting biases. Also, although social desirability may be attributed to individuals’ responses to self-reported measures such as discrimination, the measures are similar to those used by other studies of discrimination.16,17,71,72 Additionally, in a study examining self-reported discrimination and mental disorders, Gee et al. found that a measure of social desirability did not explain the association between the variables.31

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our study provides further evidence for the role of discrimination as a critical factor in service use among Asian Americans. Furthermore, it demonstrates that discrimination is correlated with informal service use. It is particularly relevant for immigrant Asian American populations, who may be further hampered in the US mental health system by issues of language proficiency and discriminatory attitudes. Thus, our study has implications for such current trends in the service delivery system as the use of community health workers and peer support. It also stresses the need for academic institutions to continue to recruit and educate culturally appropriate, bilingual providers. Negligence in dealing with these trends could lead to continued inequality and injustice among 1 of the fastest-growing racial groups in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The National Latino and Asian American Study is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grants U01 MH62209 and U01 MH62207), with additional support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, the NLAAS staff, and the study participants, without whom this study would not be possible.

Human Participant Protection

This study used a secondary data set, thus human subject approval was not required.

References

- 1.The American Community—Asians: 2004. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; February 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, et al. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuoka JK, Breaux C, Ryujin DH. National utilization of mental health services by Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders. J Community Psychol. 1997;25(2):141–145 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung FK. The use of mental health services by ethnic minorities. : Myers HF, Wohlford P, Guzman LP, Echemendia RJ, Ethnic Minority Perspectives on Clinical Training and Services in Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1991:23–31 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu T-W, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, Nguyen TD. Ethnic population in public mental health: services choice and level of use. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(11):1429–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin K-M, Cheung F. Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(6):774–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sue S, Morishima JK, The Mental Health of Asian Americans. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bui K-VT, Takeuchi DT. Ethnic minority adolescents and the use of community mental health care services. Am J Community Psychol. 1992;20(4):403–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus K, Kessler R. Twelve month use of mental health services in the Unites States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Martin LA, Williams DR, Baser R. Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):60–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimerling R, Baumrind N. Access to specialty mental health services among women in California. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(6):729–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young K. Help Seeking for Emotional/Psychological Problems Among Chinese Americans in the Los Angeles Area: An Examination of the Effects of Acculturation. Los Angeles: University of California; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong F, Gage SL, Tacata L. Helpseeking behavior among Filipino Americans: a cultural analysis of face and language. J Community Psychol. 2003;31(5):469–488 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer MS, Chen J. Discrimination and mental health service use among Chinese Americans. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):809–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DuBois DL, Burk-Braxton C, Swenson LP, Tevendale HD, Hardesty JL. Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: investigation of an integrative model. Child Dev. 2002;73(5):1573–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR, Willams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethn Health. 2000;5(3–4):243–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan S. Asian Americans: An Interpretive History. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takaki R. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai E, Arguelles D. The New Face of Asian Pacific America. San Francisco, CA: Asian Week; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lien P. Public resistance to electing Asian Americans in Southern California. J Asian Am Stud. 2002;5(1):51–72 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uba L. Asian Americans: Personality Pattern, Identity, and Mental Health. New York, NY: Cuilford Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umemoto K. From Vincent Chen to Joseph Ileto: Asian Pacific Americans and hate crime policy. : Ong P, The State of Asian Pacific America: Transforming Race Relations. Los Angeles, CA: LEAP Publications; 2000:243–278 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Washington, DC: US Commission on Civil Rights; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young K, Takeuchi DT. Racism. : Lee LC, Zane NWS, Handbook of Asian American Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998:401–432 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic Minority Groups in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):496–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):615–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Yip T, Takeuchi DT. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(10):1984–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):624–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):318–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):193–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickrama KAS. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1269–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rumbaut R. The crucible within: ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. Int Migr Rev. 1994;28(4):748–794 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: the impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States–born Asian adults. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(3):787–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, van Ryn M, Phelan S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):894–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uba L. Meeting the mental health needs of Asian Americans: mainstream or segregated services. Prof Psychol. 1982;13(2):215–221 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kung WW. Cultural and practical barriers to seeking mental health treatment for Chinese Americans. J Community Psychol. 2004;32(1):27–43 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leong FTL, Lau ASL. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(4):201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wynaden D, Chapman R, Orb A, McGowan S, Zeeman Z, Yeak S. Factors that influence Asian communities’ access to mental health care. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005;14(2):88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeh M, Hough RL, McCabe K, Lau A, Garland A. Parental beliefs about the causes of child problems: exploring racial/ethnic patterns. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):605–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown ER, Ojeda VD, Wyn R, Levan R. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Insurance and Health Care. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy and Research and The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chow J, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):792–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, Takeuchi DT, Zane NWS. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(4):533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uehara ES, Takeuchi DT, Smukler M. Effects of combining disparate groups in the analysis of ethnic differences: variations among Asian American mental health service consumers in level of community functioning. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22(1):83–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barry DT, Grilo CM. Cultural, psychological, and demographic correlates of willingness to use psychological services among East Asian immigrants. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(1):32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heeringa S, Warner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):221–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alegria M, Takeuchi DT, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng X. Considering context, place, and culture: The National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):208–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pennell BE, Gebier N, Chardoul S, et al. Plan and operation of the National Survey of Health and Stress, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):241–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung RC, Lin K. Help-seeking behavior among Southeast Asian refugees. J Community Psychol. 1994;22(2):109–120 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uba L. A Postmodern Psychology of Asian Americans: Creating Knowledge of a Racial Minority. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang AY, Snowden LR, Sue S. Differences between Asian and white Americans’ help seeking and utilization patterns in the Los Angeles area. J Community Psychol. 1998;26(4):317–326 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nicdao EG, Hong S, Takeuchi DT. Social support and the use of mental health services among Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Res Sociol Health Care. 2008;26:167–184 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eng E, Young R. Lay health advisors as community change agents. Fam Community Health. 1992;15:24–40 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Israel BA. Social networks and social support: implications for natural helper and community level interventions. Health Educ Q. 1985;12(1):65–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewin SA, Dick J, Pond P, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care (Cochrane Review). : The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford, England: Update Software; 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Navarro AM, Senn KL, McNicholas LJ, Kaplan RM, Roppé B, Campo MC. Por La Vida model intervention enhances use of cancer screening tests among Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(1):32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Let K, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):544–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, et al. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Detroit partnership: improving diabetes-related outcomes among African American and Latino adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1552–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han H, Lee H, Kim MT, Kim KB. Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean American women. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(2):318–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lam TK, McPhee SJ, Mock J, et al. Encouraging Vietnamese American women to obtain Pap tests through lay health worker outreach and media education. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(7):516–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, Weingarten R, Stayner D, Tebes JK. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol. 1999;6:165–187 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zane N, Yeh M. The use of culturally based variables in assessment: studies on loss of face. : Kurasaki K, Okazaki S, Sue S, Asian American Mental Health: Assessment Theories and Methods. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002:123–140 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gee GC, Chen J, Spencer M, et al. Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):677–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams DR, Spencer MS, Jackson JS. Race, stress, and physical health: the role of group identity. : Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Self and Identity: Fundamental Issues. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:71–100 [Google Scholar]