Abstract

The National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine have called for making the healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development of young people a national priority. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in the US Department of Health and Human Services is uniquely positioned to help develop national mental health policies that promote mental health and prevent mental illnesses.

In this article I describe the role of mental health in overall health, I make the case for a public health approach to mental health promotion and mental illness prevention, and I outline a strategy to promote individual, family, and community resilience. I also describe how SAMHSA works to achieve these goals.

Ultimately, true health reform will not succeed without a comprehensive, committed focus on the mental health needs of all Americans.

IN 2009, THE NATIONAL REsearch Council and the Institute of Medicine released the much-anticipated report Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities.1 The report, which called for making the healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development of young people a national priority, was commissioned by the Center for Mental Health Services in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department of Health and Human Services. In recommending the inclusion of mental health promotion in the full spectrum of mental health interventions, this report aligns squarely with calls to adopt a proactive public health approach to improve mental health in the United States.

The report's authors concluded that “the nation is now well positioned to equip young people with the skills, interests, assets, and health habits needed to live healthy, happy, and productive lives in caring relationships that strengthen the social fabric.”1(p13) This perspective must be the foundation of efforts not only to transform the delivery of behavioral health care in this country but also to alter the very concept of health itself. The stakes are high; as the World Health Organization notes, mental health is “central to building a healthy, inclusive, and productive society.”2

THE CASE FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

There isn't a moment to lose in efforts to promote mental health in this country. When measured across all age groups, mental illnesses are among the leading causes of disability worldwide (Table 1).3 The financial costs are staggering: by 2014, US expenditures on mental health and substance abuse treatment are projected to reach $239 billion.4 The costs in human suffering, however, are incalculable. The majority of lifetime mental illnesses begin in young people. Half of all diagnosable lifetime cases of mental illness begin by age 14, and three fourths of all lifetime cases start by age 24.5 There often are long delays—sometimes decades—between the first onset of symptoms and the time when individuals seek and receive treatment. These delays increase morbidity and prolong recovery, but recent research has found that early interventions yielded positive results for children, families, and communities.6

TABLE 1.

Leading Causes of Years Lost to Disability (YLD), by Gender: Worldwide, 2004

| Rank | Cause | YLD (in Millions) | Percentage of Total YLD |

| Males | |||

| Rank | |||

| 1 | Unipolar depressive disorders | 24.3 | 8.3 |

| 2 | Alcohol use disorders | 19.9 | 6.8 |

| 3 | Hearing loss, adult onset | 14.1 | 4.8 |

| 4 | Refractive errors | 13.8 | 4.7 |

| 5 | Schizophrenia | 8.3 | 2.8 |

| 6 | Cataracts | 7.9 | 2.7 |

| 7 | Bipolar disorder | 7.3 | 2.5 |

| 8 | COPD | 6.9 | 2.4 |

| 9 | Asthma | 6.6 | 2.2 |

| 10 | Falls | 6.3 | 2.2 |

| Females | |||

| Rank | |||

| 1 | Unipolar depressive disorders | 41.0 | 13.4 |

| 2 | Refractive errors | 14.0 | 4.6 |

| 3 | Hearing loss, adult onset | 13.3 | 4.3 |

| 4 | Cataracts | 9.9 | 3.2 |

| 5 | Osteoarthritis | 9.5 | 3.1 |

| 6 | Schizophrenia | 8.0 | 2.6 |

| 7 | Anemia | 7.4 | 2.4 |

| 8 | Bipolar disorder | 7.1 | 2.3 |

| 9 | Birth asphyxia and birth trauma | 6.9 | 2.3 |

| 10 | Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 5.8 | 1.9 |

Note. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Source. World Health Organization.3

Progress in neuroscience, molecular biology, and genomics provides the foundation for understanding the prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders and the promotion of mental health. This fact underscores the importance of positive early experiences in building a foundation for all subsequent learning, behavior, and health.7 One of the preeminent thinkers and researchers in this field is Mark Greenberg, director of the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies curriculum, an evidence-based preventive intervention for young children. He has concluded that most efforts to prevent drug and alcohol abuse, teen pregnancy, and violence—often conducted by separate, categorically funded programs—neglect opportunities to promote the healthy behaviors that could forestall these negative outcomes.

Greenberg says,

If we teach children from the beginning, early in their school years, how to become effective problem solvers, how to have self-control, [and] how to show emotional regulation, when they get to categorical problems, like AIDS issues or sexuality or violence … they'll have the underlying skills that are necessary to help them manage these problems.8(p15)

This principle is the rationale governing SAMHSA's Linking Actions for Unmet Needs in Children's Health initiative, launched in 2008 to promote the wellness of young children. This initiative defines wellness as a state of positive physical, emotional, social, and behavioral health. The initiative's goal is to create healthy, safe, supportive environments for children, allowing them to enter school ready to learn and succeed.

MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Mental health is much more than the absence of mental illness; it is what makes life enjoyable, productive, and fulfilling, and it contributes to social capital and economic development in societies.2 A decade ago, the US surgeon general's report on mental health offered important distinctions between the terms “mental health” and “mental illness.” “Mental health,” the surgeon general said, “is a state of successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and to cope with adversity.”9(p4) Personal well-being, satisfying family and interpersonal relationships, and positive contributions to community or society are all made possible by mental health.9

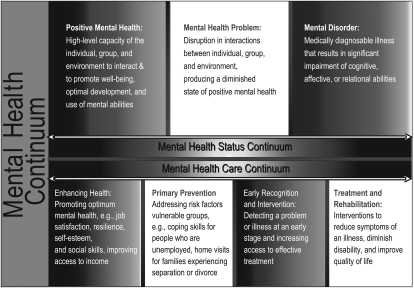

At the other end of the continuum is mental illness, a term that refers collectively to disorders that are characterized by “alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior … associated with distress and/or impaired functioning.”9(p5) Though mental disorders were once believed to be debilitating lifelong conditions, the surgeon general's report made clear that when individuals with mental illnesses receive the right combination of treatment and support, and when they have a voice in decisions concerning their care, they can and do recover (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Mental health viewed as a continuum.

Mental health is intimately connected with physical health and well-being. In a 2003 report, the New Freedom Commission on Mental Health envisioned a society in which “Americans understand that mental health is essential to overall health.”10 This signaled a shift from a reactive, deficits-based model of treatment and intervention to a proactive, strengths-based model of promotion and prevention.

DISEASE PREVENTION AND HEALTH PROMOTION

Mental illness prevention and mental health promotion are related, complementary activities, but each component has an important, distinct role. Prevention emphasizes the avoidance of risk factors; promotion aims to enhance an individual's ability to achieve a positive sense of self-esteem, mastery, well-being, and social inclusion. Equally important, mental health promotion activities are designed to strengthen an individual's ability to cope with adversity.1

Promoting mental health goes beyond a focus on the individual. When mental health is valued, “decisions taken by government and business improve rather than compromise the population's mental health, and people can make informed choices about their behavior.”11(p42) Mental health promotion means that policymakers must consider the mental health implications of all public policy.2

A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH

Mental health promotion is predicated on the understanding that the mind and the body are inseparable. So-called Cartesian dualism—a principle named for French philosopher René Descartes, who viewed the “mind” as completely separate from the “body”—underlies the belief in the separation between “mental” and “physical” health that persists to this day, despite nearly a century of scientific evidence to the contrary (e.g., Canon12 and Selye13). The notion that either mental or physical health can exist alone is a significant barrier to support for mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment.11 Such preconceptions can even be deadly. Research has found that individuals with the most serious mental illnesses died at age 53 years, on average.14 Individuals in the study samples died from treatable medical conditions caused by modifiable risk factors, including smoking, obesity, substance use, and inadequate access to medical care.14

The recently enacted Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, with its requirement that all benefit packages in health exchanges include coverage for treatment of mental illnesses and substance use disorders at parity with the medical or surgical benefit, demonstrates that behavioral health has come of age. Just as mental health is part of overall health, so too is the promotion of mental health integral to health promotion and public health.

In an oft-cited seminal work, the Institute of Medicine defined public health as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.”15(p1) Developing effective public policies designed to promote mental health and prevent mental illnesses requires assessing the health of communities and individuals and providing assurance that they will have the care they need. Ultimately, the public health approach is “an optimistic approach that provides tools for individuals and communities to proceed in a positive, problem-solving manner.”16(p14)

Because mind and body are one, many of the interventions designed to improve mental health will also promote physical health and vice versa. One such approach is to embed mental health promotion activities in existing health promotion programs. Examples include providing support to families to improve nurturing of children, thereby reducing the chances of child abuse and neglect; addressing physical health, bullying, and aggression in schools; and supporting the care of older adults.11

SPECIFIC ACTIVITIES TO PROMOTE MENTAL HEALTH

The new report by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine presents a road map for improving the mental health of the nation. First, we must target interventions to strengthen individuals by building their resilience. Resilience is not something that an individual either has or doesn't have; it involves thoughts and behaviors that can be learned and developed.16 In fact, a significant body of mental health research suggests that certain individual strengths can act as protective barriers against the onset of mental health problems. These strengths include courage, hope, optimism, interpersonal skills, and perseverance, among others. Such character traits function as a buffer against adversity and psychological disorders, and they may be the key to resilience.16,17

But individuals cannot be nurtured in isolation. We also must strengthen families because strong, healthy families support resilient, mentally healthy individuals. Improved family functioning and positive parenting serve as mediators of positive outcomes and can moderate poverty-related risks.1 Finally, we must strengthen the communities in which individuals live, work, learn, and play. To improve the overall health of individuals and the communities in which they live, we must address the personal, social, economic, and environmental determinants of health. For individuals with mental health problems, this means focusing on such issues as poverty, widespread unemployment, and inequitable distribution of health care resources. Changes in social policy that reduce exposure to poverty-related risks are at least as important as other interventions for preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders in young people.1

Promoting individual, family, and community resilience requires a 3-pronged approach. First, we must disseminate evidence-based promotion and prevention programs across a range of family, school, and community settings. Priority must be given to programs that have been tested and replicated in real-world environments, that have reasonable costs, and that are supported by tools that will help those using the programs to implement key elements with fidelity. Mental health and substance abuse interventions that have been scientifically tested and can be readily disseminated are listed in SAMHSA's National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices, a searchable database of interventions for the promotion of mental health and the prevention and treatment of mental and substance use disorders.

Second, we also must pursue rigorous scientific inquiry—including research into the promotion of mental health—that aims to improve both the quality and the implementation of interventions across diverse settings. Along these lines, SAMSHA is working with partners at the National Institute of Mental Health to implement a comprehensive science-to-service agenda.

Finally, we must increase public understanding and acceptance of mental health promotion and mental illness prevention. Lack of public understanding or support for promotion and prevention increases the likelihood that society will fail to prevent the development of problems in childhood and adolescence.1 SAMHSA's Campaign for Mental Health Recovery is a national public education effort designed to improve the general understanding of mental illnesses, promote recovery, and encourage help-seeking behaviors across the life span. The campaign's first theme, “What a Difference a Friend Makes,” aims to educate and encourage people aged 18 to 25 years to support friends who are experiencing a mental health problem. Our new teen suicide prevention campaign, “We Can Help Us,” links teens to others who have struggled with difficult emotions.

SAMHSA is also a sponsor of This Emotional Life, a groundbreaking PBS series that examines the latest biological and social science behind human nature to better understand what drives emotions and what leads to greater fulfillment. In addition, SAMHSA is a sponsor of Bring Change 2 Mind, a nonprofit organization founded by actress Glenn Close that works to dispel misconceptions about mental illnesses and provide access to information and support.

COLLABORATION FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

The work of promoting mental health and preventing mental illnesses must be a wide-ranging effort that includes individuals, volunteer organizations, governments, industry, and the media. SAMHSA is proud to lead a broad-based coalition called Federal Partners for Mental Health, which comprises representatives from more than 20 federal agencies and offices that have been meeting for more than 5 years to create more rational, accessible, and transparent mental health care. Together, the Federal Partners coalition created the Federal Action Agenda,18,19 which is both a vision and a plan to achieve optimal mental health for all citizens and recovery and wellness for individuals with mental disorders. The ongoing work of the Federal Partners has already resulted in such achievements as the development of materials that support integrated care for mental and general health conditions and enhanced services for veterans and active-duty military at risk for suicide.

Ultimately, if health promotion principles are to drive mental health policies and programs, they must be legitimized as part of a national agenda.20 Comprehensive agendas for mental health promotion and mental illness prevention have been developed in a number of countries, including Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. In the United States, SAMHSA is uniquely positioned to help lead the effort toward development of national mental health policies. Congress created SAMHSA in 1992 “to improve the provision of treatment and related services to individuals with respect to substance abuse and mental illness” and “to improve prevention services, [and] promote mental health.”21

SAMHSA can provide critical leadership by laying the groundwork for development of national mental health policies and by supporting fiscal policies that promote holistic, person-centered health care. We can do this by

building the information base for mental health promotion;

promoting the science and practice of public health;

strengthening the connections between science and service;

harnessing evolving communication technology;

supporting integrated health care models;

training and developing 21st-century health care leaders; and

emphasizing the importance of performance management to ensure that programs and services achieve the desired results.

MOVING FORWARD

Professionals in mental health and public health must work together with concerned citizens to help all Americans understand that mental health is essential for overall health. We should band together to cultivate strong, enlightened leaders who acknowledge that the mental health implications of public policies are as important as—if not more important than—their political or economic impact. I urge us not to waver in our dedication to translate the science of mental health promotion and mental illness prevention into services that improve the lives of individuals of all ages. Ultimately, true health reform cannot and will not succeed without a comprehensive, committed focus on the mental health of all Americans.

References

- 1.National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan for Europe: Facing the Challenges, Building Solutions. Helsinki, Finland: World Health Organization; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levit KR, Kassed CA, Coffey RM, et al. Projections of National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment, 2004–2014. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. DHHS publication SMA-08-4326 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Young Children and Their Families. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shonkoff JP. Mobilizing science to revitalize early childhood policy. Issues Sci Technol. 2009;Fall:79–85 [Google Scholar]

- 8.DuPont NC. Update on Emotional Competency: Helping to Prepare Our Youth to Become Effective Adults. Cranston RI: Rhode Island Department of Mental Health, Retardation, and Hospitals; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. DHHS publication SMA-03-3832 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermann H, Jané-Llopis E. Mental health promotion in public health. Promot Educ. 2005;12:42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canon WB. The Wisdom of the Body. New York, NY: Norton; 1926 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selye H. The Stress of Life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME. Morbidity and Mortality in People With Serious Mental Illness. Alexandria, VA: Medical Directors Council, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis NJ. The promotion of mental health and the prevention of mental and behavioral disorders: surely the time is right. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2002;4(1):3–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Federal Action Agenda: First Steps. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2005. DHHS publication SMA-05-4060 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Federal Action Agenda: “A Living Agenda.” Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. DHHS publication SMA-08-4060 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandiver VL. Integrating Health Promotion & Mental Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Public Law 102-321. Subtitle A, Section 101(d)(2), July 10, 1992. [Google Scholar]