Abstract

Objectives. We examined racial/ethnic discrimination experiences of Chinese American adolescents to determine how discrimination is linked to poor adjustment (i.e., loneliness, anxiety, and somatization) and how the context of the family can buffer or exacerbate these links.

Methods. We collected survey data from 181 Chinese American adolescents and their parents in Northern California. We conducted hierarchical regression analyses to examine main effects and 2-way interactions of perceived discrimination with family conflict and family cohesion.

Results. Discrimination was related to poorer adjustment in terms of loneliness, anxiety, and somatization, but family conflict and cohesion modified these relations. Greater family conflict exacerbated the negative effects of discrimination, and greater family cohesion buffered the negative effects of discrimination.

Conclusions. Our findings highlight the importance of identifying family-level moderators to help adolescents and their families handle experiences of discrimination.

Discrimination is one of the most significant stressors facing adolescents in immigrant families, especially those who are ethnic minorities.1–4 Discrimination is robustly linked to a host of negative outcomes for immigrants of Asian background, at least among college students and adults. These negative outcomes include lower levels of social competence, social connectedness, and self-esteem, and higher levels of substance abuse, depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and chronic illness (i.e., heart disease, pain, and respiratory illnesses).5–9 However, there are few studies of younger populations that include Asian American adolescents.

Although discrimination at any age is harmful, there are several reasons to focus on discrimination during adolescence. Adolescents who experience discrimination adjust more poorly in terms of having lower self-esteem and more depressive symptoms.10–12 Further, adolescents have fewer and less sophisticated coping strategies to deal with stressors (such as discrimination) than do adults.13 Finally, adolescence is a time when issues of identity, self-concept, and self-esteem come to the fore.14,15 Thus, assaults on a person's sense of self may be particularly harmful during this developmental period, when the adolescent's sense of self is still emerging. To address the lack of literature on discrimination among Asian American adolescents, we examined the racial/ethnic discrimination experiences of Chinese American adolescents to determine how discrimination is linked to poorer adjustment (i.e., loneliness, anxiety, and somatization) and how the context of the family can buffer or exacerbate these links.

LONELINESS, ANXIETY, AND SOMATIZATION

Loneliness has been defined as the “aversive state experienced when a discrepancy exists between the interpersonal relationships one wishes to have, and those that one perceives they currently have.”16(p698) Loneliness appears to peak during adolescence.16 Given the rejection implied by experiences of discrimination, we expect that greater discrimination is associated with greater loneliness. In addition to loneliness, we focused on anxiety. Anxiety may be of particular concern for Asian American populations. Asian American college students, for instance, have reported greater anxiety than have European American college students17 and greater anxiety when facing discrimination than have Latino college students.18 We expect that discrimination is linked to anxiety for Asian American adolescents as well. We also focused on somatization as an indicator of poor physical adjustment. Although an association between discrimination and physical health has been found among Asian American adults,5 this association has yet to be examined among Asian American adolescents. In sum, we expect that greater perceptions of discrimination will be associated with greater adolescent loneliness, anxiety, and somatization.

PERCEIVED DISCRIMINATION AS A RISK FACTOR

We consider perceived discrimination to be a risk factor that threatens positive adolescent development. Risk factors have been defined as “individual or environmental hazards that increase an individual's vulnerability for negative developmental behaviors, events, or outcomes.”19(p385) Not all children and adolescents, however, react the same way when exposed to the same risks.20 There is an important context that can either exacerbate or combat risk: the family.20–22 Although the family has long been recognized as a key context for adolescent adjustment, little research has focused on how families can exacerbate or alleviate the effects of discrimination in particular.23

FAMILY CONFLICT AND COHESION

Family conflict is a vulnerability factor,21 given that a negative family climate is a major contributor to a variety of psychological problems for children and adolescents in immigrant families.24–27 Notably, family conflict may have particularly dire consequences for adolescents of Chinese background because Chinese culture emphasizes family interdependence, obligation, and cohesion. Because a conflictual family environment may add to adolescent distress, we hypothesize that greater family conflict would exacerbate the negative effects of discrimination.

In contrast to family conflict, family cohesion is a protective factor.21 Family cohesion is defined as having a close, connected relationship with family members.28 Greater family cohesion has been linked to less distress among Asian American adults9 and less family conflict among Asian American college students25 and Filipino and Chinese adolescents.29 Few studies, however, have considered how family cohesion may moderate the impact of negative events. One study of Asian American adults found that family support buffered the negative effects of discrimination.7 Because a cohesive family can offer support in times of distress, we hypothesized that greater family cohesion would buffer the negative effects of adolescents' perceived discrimination.

METHODS

We drew our sample from San Francisco, California, an ethnically diverse city whose population is 31.3% Asians and Pacific Islanders. Chinese Americans are the largest group among the city's Asians and Pacific Islanders (19.6%).30 San Francisco has a rich history of Chinese immigration, starting in the mid-1800s. Today San Francisco is a culturally vibrant city with a strong and highly visible Chinese American community.

Recruitment

We recruited adolescents from 2 San Francisco high schools with large Chinese American populations; more than half of the students in each school came from Chinese immigrant backgrounds (N = 1366). For this study, 23% of the Chinese American students in the 2 schools (n = 309) participated. Overall, the school contexts reflected a diversity of ethnic groups, as did the larger community, but the school populations included an overrepresentation of Asians. To achieve an adequate sample size with sufficient power for multivariate analyses, we targeted these 2 schools precisely because they had higher proportions of Chinese American students.

We went to the 2 target schools and made announcements about the study to school assemblies and to after-school clubs geared toward students of Chinese background. We handed out consent forms at the assemblies and clubs for adolescents to take home to their parents. We also posted fliers at the schools describing the study. The announcements and fliers stated that we were interested in Chinese American adolescents' experiences of growing up in the San Francisco area. Interested adolescents could pick up consent forms at a designated classroom. Those who obtained a signed guardian or parent consent form and signed an assent form were given the survey. Adolescents completed the survey during classroom hours or immediately after school. Parents were not present during survey completion. Adolescents were compensated $15 each. Adolescents who completed the survey were given a parent survey packet to take home, with instructions for their parents to complete the survey and mail it back to the researchers. Parents were also compensated $15 each for completing a survey. We collected surveys from June 2001 through October 2001.

Measures

The adolescents completed items measuring perceived discrimination, loneliness, anxiety, and somatization. Parents completed items measuring family conflict and cohesion.

Perceived discrimination.

Adolescents' perceptions of discrimination were measured by 3 items: “How often have you been treated unfairly because you are Asian?” “How often do people dislike you because you are Asian?” “How often have you seen friends or family be treated unfairly because they are Asian?”31 The response scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Mean scores were calculated so that a higher score indicated greater discrimination. The Cronbach α was 0.82.

Loneliness.

The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale32 is the most widely used measure of loneliness, consisting of 20 items measuring the discrepancy between desired levels of social contact and achieved levels of social contact. Adolescents indicated the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “I lack companionship” and “I feel part of a group of friends,” using a scale of 1 (never) to 4 (often). Positive items were reverse-coded and mean scores were calculated so that a higher score indicated more loneliness. The Cronbach α was 0.89.

Anxiety and somatization.

Two subscales from the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory33 were used to measure anxiety and somatization. For anxiety (6 items), adolescents reported how much a series of problems (e.g., “nervousness or shakiness inside,” “suddenly scared for no reason”) had caused them distress in the previous 7 days. For somatization (7 items), adolescents reported how much a series of problems (e.g., “nausea or upset stomach,” “pains in the heart and chest”) had caused them distress in the previous 7 days. Both response scales ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Mean scores for each subscale were calculated so that a higher score indicated greater anxiety and greater somatization. The Cronbach α for anxiety was 0.83; the Cronbach α for somatization was 0.83.

Family conflict.

The Asian American Family Conflicts Scale-Likelihood25 consists of 10 items measuring the likelihood of intergenerational family conflict typical in Asian American families. We modified the original scale for use with parents. Parents used a scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always) to rate the likelihood of certain situations occurring, such as “You want your children to sacrifice their personal interests for the sake of the family, but they feel this is unfair.” Mean scores were calculated so that higher scores indicated a greater likelihood of conflict. The Cronbach α was 0.87.

Family cohesion.

We used the family cohesion subscale from the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales II28 to assess the degree of emotional closeness among family members. This 16-item subscale has been widely used in family research and found to be reliable and valid with Chinese American families and adolescents.29,34 Parents responded to such items as “Family members feel very close to each other” on a scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Mean scores were calculated so that higher scores indicated greater family cohesion. The Cronbach α was 0.84.

RESULTS

For this study we included only adolescents who had parent survey data. This restricted sample consisted of 181 (57% of the larger Chinese American adolescent sample of 309) 9th- and 10th-grade Chinese American adolescents and their parents. The adolescents' mean age was 14.8 years (SD = 0.74), ranging from 13 to 17 years; 63% were female. A majority (66%) of the adolescents were US born, and 29% percent were foreign born. Most of the adolescents grew up with both parents (89%), and most had at least 1 sibling (86%).

Most of the parents who filled out the parent survey were mothers (71%). Of these, 4% had completed elementary school or less, 11% had attended middle school, 15% had attended some high school, 31% had graduated from high school, 19% had attended some college or university, and 20% had graduated from college or university or more. For fathers who filled out the parent survey, 7% had completed elementary school or less, 15% had attended middle school, 16% had attended some high school, 28% had graduated from high school, 16% had attended some college or university, and 19% had graduated from college or university or more.

To test whether the adolescents with parent data differed from adolescents without parent data, we compared the 2 groups on age, gender distribution, immigrant status (US born vs foreign born), parent education, adolescent-perceived discrimination, loneliness, anxiety, and somatization. Adolescents with parent data did not differ from adolescents without parent data with regard to age (t307 = −1.78; P = .08), immigrant status (χ21 = 2.04; P = .17), mother education (t302 = −0.36; P = .72), father education (t298 = 0.12, P = .91), perceived discrimination (t307 = −1.25; P = .21), loneliness (t307 = 0.93; P = .35), anxiety (t307 = −0.14; P = .89), or somatization (t307 = 0.03; P = .97). The 2 groups differed in gender distribution (χ21 = 6.93; P = .008); females constituted a higher proportion of adolescents with parent data (63% females) than of adolescents without parent data (48% females).

Table 1 presents descriptives and bivariate correlations for the main study variables. We first examined whether demographic variables (age, gender, immigrant status, and mother and father education) accounted for variance among the 3 dependent variables (loneliness, anxiety, and somatization). Only maternal education was positively related to somatization (r = 0.18; P = .015). No other demographic variable was related to any of the other dependent variables. Thus, maternal education was controlled for in the analyses for somatization.

TABLE 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptives of Main Study Variables: Chinese American Adolescents (n = 181), San Francisco, CA, 2001

| Perceived Discriminationa | Lonelinessa | Anxietya | Somatizationa | Family Conflictb | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Perceived Discriminationa | … | … | … | … | … | 1.86 (0.68) | 1–5 |

| Lonelinessa | 0.31† | … | … | … | … | 1.81 (0.44) | 1–4 |

| Anxietya | 0.34† | 0.51† | … | … | … | 1.81 (0.78) | 1–5 |

| Somatizationa | 0.29† | 0.42† | 0.64† | … | … | 1.62 (0.62) | 1–5 |

| Family conflictb | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.03 | … | 2.50 (0.81) | 1–5 |

| Family cohesionb | 0.02 | −0.14* | −0.17** | −0.14* | −0.14* | 3.65 (0.49) | 1–5 |

Note. Ellipses indicate that results are not applicable.

Based on adolescent report.

Based on parent report.

*P = .06; **P < .05; †P < .001.

We used hierarchical multiple regressions to test our hypotheses. All variables included in interactions were first centered to reduce multicollinearity. We conducted 3 regressions to examine predictors of adolescent loneliness, anxiety, and somatization. In step 1, we entered perceived discrimination (with the exception of analyses with somatization that entered maternal education as step 1). In step 2, we entered family conflict and cohesion as a block. In step 3, we entered 2 interactions as a block: discrimination by family conflict and discrimination by family cohesion.

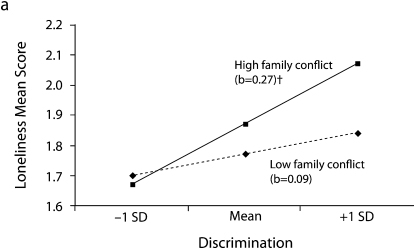

As hypothesized, there was a main effect of discrimination on loneliness (Table 2). Those adolescents who reported greater perceived discrimination also reported greater loneliness. Family cohesion—but not family conflict—was directly related to loneliness, so that greater family cohesion was related to less adolescent loneliness. There was also a significant family conflict by discrimination interaction. To clarify this interaction, we used Holmbeck's method35 for post hoc probing of significant moderation effects. Family conflict was dichotomized by a median split to distinguish families with high levels of conflict from families with low levels of conflict. Post hoc analyses showed that discrimination was unrelated to loneliness for adolescents with low levels of family conflict, and that discrimination was positively related to loneliness for adolescents with high levels of family conflict, such that greater discrimination was related to more loneliness (Figure 1a).

TABLE 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Adolescent Adjustment on Perceived Discrimination, Family Conflict, and Family Cohesion: Chinese American Adolescents (n = 181), San Francisco, CA, 2001

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

| Variable | b (SE) | B | b (SE) | B | b (SE) | B | b (SE) | B |

| Loneliness | ||||||||

| Perceived discrimination | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.31† | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.30† | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.28† | ||

| Family conflict | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.08 | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.08 | ||||

| Family cohesion | −0.12 (0.06) | −0.14** | −0.12 (0.06) | −0.14** | ||||

| Perceived discrimination × family conflict | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.15** | ||||||

| Perceived discrimination × family cohesion | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.03 | ||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| Perceived discrimination | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.34† | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.34† | 0.32 (0.08) | 0.28† | ||

| Family conflict | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.05 | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.03 | ||||

| Family cohesion | −0.28 (0.11) | −0.17** | −0.30 (0.11) | −0.19*** | ||||

| Perceived discrimination × family conflict | 0.22 (0.09) | 0.16** | ||||||

| Perceived discrimination × family cohesion | −39 (0.16) | −0.17** | ||||||

| Somatization | ||||||||

| Maternal educationa | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.18** | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.24*** | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.24*** | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.23*** |

| Perceived discrimination | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.34† | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.34† | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.30† | ||

| Family conflict | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.02 | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.02 | ||||

| Family cohesion | −0.16 (0.09) | −0.11 | −0.16 (0.09) | −0.12 | ||||

| Perceived discrimination × family conflict | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.12 | ||||||

| Perceived discrimination × family cohesion | −0.14 (0.13) | −0.08 | ||||||

Note. Perceived discrimination is based on adolescent report; family conflict and family cohesion are based on parent report.

Maternal education is coded as: 1 = completed elementary school or less, 2 = attended middle school, 3 = attended some high school, 4 = graduated from high school, 5 = attended some college or university, and 6 = graduated from college or university or more.

**P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001.

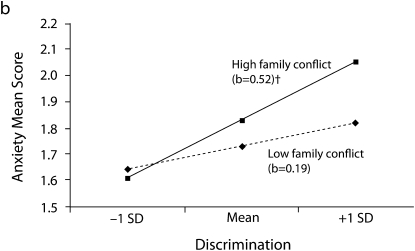

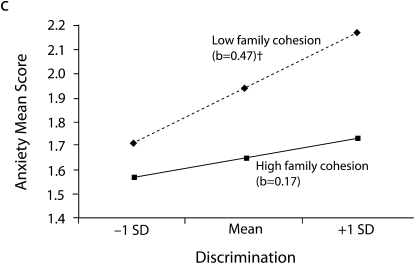

FIGURE 1.

Regression lines for relations between perceived discrimination and (a) loneliness and family conflict, (b) anxiety and family conflict, and (c) anxiety and family cohesion: Chinese American adolescents, San Francisco, CA, 2001.

Note. Data presented here describe a 2-way interaction. The sample size was n = 181.

†P < .001.

Also as hypothesized, there was a main effect of discrimination on anxiety (Table 2). Those adolescents who reported greater perceived discrimination reported greater anxiety. Family conflict was not directly related to anxiety, but cohesion was directly related to anxiety such that greater family cohesion was linked to less adolescent anxiety. Interpretation of these findings is tempered by 2 statistically significant interactions that emerged: family conflict by discrimination for anxiety, and family cohesion by discrimination for anxiety. Post hoc analyses showed that discrimination was unrelated to anxiety for adolescents with low levels of family conflict but was positively related to anxiety for those with high levels of family conflict; thus, greater discrimination was related to more anxiety (Figure 1b). Furthermore, discrimination was unrelated to anxiety for adolescents with high levels of family cohesion but was positively related to anxiety for those with low levels of family cohesion; thus, greater discrimination was associated with more anxiety (Figure 1c).

As hypothesized, there was a main effect of discrimination on somatization (Table 2). After controlling for maternal education, adolescents who reported greater perceived discrimination also reported greater somatization. Family conflict and cohesion were not directly related to somatization, and no interactions were detected.

DISCUSSION

Although discrimination is hurtful at any point in life, adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to discrimination because of the developmental issues—e.g., an emerging sense of self, the importance of peers—that define adolescence. We examined how family interactions either exacerbated or buffered the negative effects of discrimination during adolescence. Discrimination was related to poorer adjustment in terms of loneliness, anxiety, and somatization, but family conflict and cohesion modified these relations. Specifically, greater family conflict exacerbated the negative effects of discrimination, and greater family cohesion buffered the negative effects of discrimination. Our findings highlight the importance of identifying family-level moderators to help adolescents and their families handle experiences of discrimination. Doing so moves us beyond targeting only individual-level characteristics—developing a stronger ethnic identity or learning personal coping strategies—when helping adolescents deal with discrimination.

Discrimination Linked to Adolescents' Mental and Physical Health

In accordance with previous studies,10–12 our results show that discrimination was associated with negative adjustment in terms of loneliness, anxiety, and somatization. The combination of an emerging sense of self and identity during adolescence and experiences of discrimination directly targeting one's sense of self creates a context of risk for greater loneliness. Because loneliness, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem may be interrelated,36,37 it is possible that discrimination increases adolescents' sense of loneliness; this, in turn, may increase depressive symptoms and decrease self-esteem. Indeed, if loneliness is shown to be a key mediator of such relations, intervention programs that bolster adolescents' networks of support (familial or peer) may be critical in combating the negative effects of discrimination.

In addition to loneliness, discrimination is also linked to anxiety and somatization. Thus, discrimination is associated with both psychosocial and physical manifestations of adjustment. Although discrimination has been linked to physical illnesses such as heart disease, pain, and respiratory illnesses among adults,5,9 our study of adolescents shows links to physical disturbances in a much younger sample. Prolonged exposure to discrimination, starting in childhood and adolescence, could be a risk factor for later adult illness and diseases. The physical illnesses we see in adulthood could be foreshadowed by processes set in motion much earlier in life.

Family Conflict and Family Cohesion Matter

The findings of the current study are consistent with evidence that discrimination is associated with poorer adjustment, but our results also highlight the complexity of these relations. At low levels of discrimination, the adolescents in our sample showed comparable adjustment; at high levels, however, family interactions mattered. Negative family interactions exacerbated the effects of perceived discrimination, and positive interactions buffered the effects of greater perceived discrimination.

Family conflict exacerbated the effects of discrimination on loneliness and anxiety. Adolescents who felt lonely because their sense of self was being denigrated by people outside the family did worse when the adolescents were also engaged in conflict with parents at home. Thus, experiencing challenges in multiple contexts compounded feelings of loneliness and anxiety. In the language that Luthar et al.21 suggested to more precisely label vulnerability factors, family conflict appears to be a “vulnerable-reactive” factor—one that heightens the disadvantages associated with increasing levels of risk or stress.

We found that family cohesion did not buffer against feelings of greater loneliness associated with discrimination. Because the importance of peers is heightened during adolescence, familial support may not be enough to overcome feelings of loneliness. Future research could investigate whether peer support buffers effects of discrimination. Adopting an ecological perspective and including multiple contexts will be important for understanding how different microsystems (such as the family and the peer group) interact and collectively affect an adolescent's experience of discrimination.

Family cohesion did, however, buffer the effects of discrimination on anxiety. Adolescents who were able to rely on their parents for support, companionship, and comfort reported much less distress, even when facing higher levels of discrimination. Indeed, levels of anxiety among adolescents with supportive parents were as low as levels among those who experienced much less discrimination. Family cohesion appears to be a protective-stabilizing factor,21 providing some protection against disadvantages despite increasing levels of risk or stress.

It is encouraging that family cohesion buffered the negative effects of discrimination (at least for anxiety) because it may be difficult for some parents to openly discuss discrimination and how to cope with it. In African American families, most parents actively socialize their children to deal with racism and discrimination; for instance, many African American parents engage their children in discussions to prepare them to face these experiences.38 However, little is known about how families of other racial/ethnic backgrounds socialize their children to handle racism and discrimination.39 Anecdotal evidence suggests that in some Asian American families, open discussion of racism and discrimination may be discouraged.40 Also, Asian cultural values emphasize that dwelling on upsetting thoughts or events will only exacerbate the problem.41 Consequently, it may be useful for intervention and prevention programs geared toward Asian American families to highlight alternate strategies in addition to verbally discussing how to cope with experiences of racism and discrimination.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study has several limitations. First, the study was cross-sectional; therefore, we cannot determine the direction of effects between discrimination and poor adjustment. There are, however, a handful of longitudinal studies suggesting that experiences of discrimination lead to poorer adjustment among adolescents.11,12 Future research could examine the interplay between discrimination, adjustment, and family context over time to better understand how family processes contribute to discrimination and its consequences.

The second limitation is that we had a restricted sample of adolescents with parent data. Although such adolescents did not differ greatly from their counterparts without parent data, our sample may not be representative of the broader population of Chinese American families. However, because most studies of discrimination among adolescents include only adolescent-reported data, our study has the advantage of offering a parent perspective on family functioning. The third limitation is that we did not have information on adolescents and parents who did not participate in the study. Thus, the findings and conclusions of the study are limited to families who are amenable to participating in a research study, thereby reflecting a selection bias.

The fourth limitation is the use of interaction analyses to test for moderation effects. The effect sizes reported in our study are small, which is a common finding.42,43 Nonetheless, studies of interactive effects show how and when risk factors can negatively affect development.44 The identification of factors amenable to modification, such as parental support, offers important information for the development of effective interventions.44 Future research should continue the search for moderators to identify malleable variables that have the potential to counter the deleterious effects of discrimination.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant MH61573).

We are grateful to the adolescents and parents who participated in the study and to the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful comments on the article.

Human Participant Protection

The study protocol was approved by San Francisco State University's institutional review board.

References

- 1.García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Dev. 1996;67(5):1891–1914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portes A, Rumbaut R. Legacies: The Story of the Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portes A, Rumbaut R. Immigrant America: A Portrait. 2nd ed.Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero AJ, Carvajal SC, Valle F, Orduña M. Adolescent bicultural stress and its impact on mental well-being among Latinos, Asian Americans, and European Americans. J Community Psychol. 2007;35(4):519–534 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Takeuchi D. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1275–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(1):36–44 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noh S, Kasper V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying YW, Lee P, Tsai J. Cultural orientation and racial discrimination: predictors of coherence in Chinese American young adults. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(4):427–442 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: the impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States–born Asian adults. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(3):787–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton R. Discrimination distress during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(6):679–695 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(2):218–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juang LP, Cookston JT. Acculturation, discrimination, and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Prim Prev. 2009;30(3–4):475–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij V, van de Kommer T, Teerds J. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. J Adolesc. 2002;25(6):603–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erikson E. Identity, Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: Norton; 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harter S. The development of self-representations during childhood and adolescence. : Leary M, Mark R, Tangney JP, Handbook of Self and Identity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:610–642 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrich L, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):695–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okazaki S. Asian American and White American differences on affective distress symptoms: do symptom reports differ across reporting methods? J Cross Cult Psychol. 2000;31(5):603–625 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang WC, Goto S. The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14(4):326–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkins D, Borden L. Problem behaviors, protective factors, and resiliency in adolescence. : Lerner R, Easterbrooks A, Mistry J, Handbook of Psychology: Developmental Psychology. Vol 6 Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2003:373–394 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner EE. Resilience in development. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1995;4(3):81–85 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luthar SS, Cichetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masten A, Garmezy N. Risk, vulnerability, and protective factors in developmental psychopathology. : Lahey B, Kazdin A, Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995:1–52 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabatier C, Berry JW. The role of family acculturation, parental style, and perceived discrimination in the adaptation of second-generation immigrant youth in France and Canada. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2008;5(2):159–185 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juang LP, Syed M, Takagi M. Intergenerational discrepancies of parental control among Chinese American families: links to family conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms. J Adolesc. 2007;30(6):965–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee R, Choe J, Ngo G, Kim V. Construction of the Asian American family conflicts scale. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47(2):211–222 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SL, Yeh M, Liang J, Lau A, McCabe K. Acculturation gap, intergenerational conflict, parenting style, and youth distress in immigrant Chinese American families. Marriage Fam Rev. 2009;45(1):84–106 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uba L. Asian Americans: Personality Patterns, Identity, and Mental Health. London, England: Guilford Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olson DH, Sprenkle DH, Russell CS. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Fam Process. 1979;18(1):3–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuligni AJ. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: a study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Dev Psychol. 1998;34(4):782–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.San Francisco City and County Bay Area Census Web site. Available at: http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/counties/SanFranciscoCounty.htm. Accessed August 16, 2010

- 31.Gil A, Vega W. Two different worlds: acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. J Soc Pers Relat. 1996;13(3):435–456 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. 4th ed.Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chao RK. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev. 2001;72(6):1832–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(1):87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen RW. The uses of loneliness in adolescence. In: Rotenberg KJ, Hymel S, Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1999:244–262 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge A. The timing of middle-childhood peer rejection and friendship: linking early behavior to early-adolescent adjustment. Child Dev. 2007;78(4):1037–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson D. The ecology of children's racial coping: family, school, and community influences. : Weisner T, Discovering Successful Pathways in Children's Development. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2003:84–109 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(5):747–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrod A, Kilkenny R. Balancing Two Worlds: Asian American College Students Tell Their Life Stories. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng D, Leong FT, Geist R. Cultural differences in psychological distress between Asian and Caucasian American college students. J Multicult Couns Devel. 1993;21(3, theme issue):182–190 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luthar SS. Annotation: methodological and conceptual issues in the study of resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34(4):441–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutter M. Statistical and personal interactions, facets, and perspectives. : Magnusson D, Allen V, Human Development: An Interactional Perspective. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1983:295–319 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roosa MW. Some thoughts on resilience, positive development, main effects versus interactions, and the value of resilience. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):567–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]