The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as “not just the absence of mental disorder” but “as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1(p2) Mental illness, on the other hand, is the “term that refers collectively to all diagnosable mental disorders” that are “health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior (or some combination thereof) associated with distress and/or impaired functioning.”2(p5)

Further, WHO has long defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease, or infirmity.”3(p100) Given these definitions, it should be clear that there is no health without mental health.

Tourists in Beijing, China, practice tai chi at a Buddist temple. Photograph by Michael Wolf. Printed with permission of Aurora Photos.

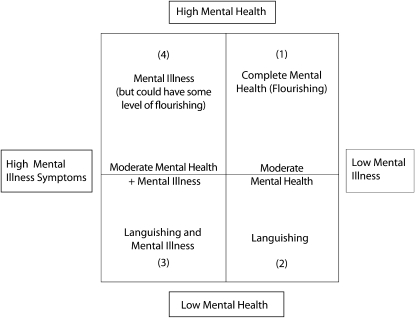

Recent arguments suggest that mental illness and mental health are related and can co-occur in individuals.4,5 This relationship is defined by the two-continuum model, which is best explained by a four-quadrant scheme that includes mental health, languishing, flourishing, and mental illness (Figure 1). In this model, Keyes considers flourishing as a state “filled with positive emotions and to be functioning well psychologically and socially,”4(p210) languishing as a state of “emptiness, and stagnation” 4(p210) in which the person describes his life as one of despair (i.e., “hollow,” “empty”), 4(p210) and mental illness as the presence of a set of symptoms (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM III R]) indicative of major depression over a 12-month period.

FIGURE 1.

Two-continuum model of mental health.

Source. Adapted from Keyes.5

In the first quadrant of this system, there is no mental illness, and a person in this quadrant experiences complete mental health, defined by Keyes as flourishing.5 People who fall into the second quadrant have moderate mental health and exhibit low symptoms of a mental illness. People who are experiencing some symptoms of mental illness and exhibit poor mental health are considered to be in a languishing state of mental health and fall into the third quadrant. The fourth quadrant is made up of those who have a high level of mental illness but who also may exhibit some degree of flourishing (i.e., exhibit a level of resilience and coping factors). At any level of mental health other than complete mental health, people do not function at optimal capacity and have some signs and symptoms of mental illness. Keyes describes states of coexistence of mental illness and mental health in an analysis of the Midlife Development in the US Study, in which he found that only 17% of the participants ages 25 to 74 years experienced complete mental health, 57% experienced some combination of mental illness and mental health, 12% were in a state of languishing, and 14% had experienced a major depressive episode in the past 12 months.4 Kessler et al. reported that an estimated 26% of persons living in the United States age 18 years and older suffered from a diagnosable mental illness in a given year.6

MENTAL HEALTH AND CHRONIC DISEASE

Epidemiologic studies have provided evidence of a strong link between mental illness, mental health, and physical health, especially as it relates to chronic disease occurrence, course, and treatment. For example, depression has been shown to affect the occurrence, treatment, and outcome of several chronic diseases and conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and obesity.7 Mental illnesses such as depression and indicators of mental illness such as frequent mental distress are related to certain risk behaviors, including physical inactivity, smoking, drinking,8 and insufficient sleep.9,10 Emerging evidence shows that positive mental health is associated with improved health outcomes. For example, in one study, individuals with mentally healthy attributes (such as optimism) had a lower risk for coronary heart disease.11 Keyes also demonstrated a significantly lower prevalence of chronic disease among those who met the criteria for complete mental health.12

Additionally, higher emotional well-being, which is an important facet of positive mental health, has been shown to be related to longevity.13 Further, in this same issue Keyes et al. show that losses of positive mental health lead to increasing risk of mental illness, and Snowden et al. show that recovery from mental illness can lead to gains in the level of positive mental health.14,15

A COMPREHENSIVE PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH IS WARRANTED

These findings suggest that public health must focus on preventing and treating mental illness but at the same time must promote mental health by addressing the emotional, social, and psychological well-being of the population. The barrier to this goal may lie in the strategies that should be used to facilitate mental health promotion. Research findings suggest that using individual approaches may have limited success for improving mental health.16 It is clear, then, that population-based interventions are needed, but to date few population-level intervention studies with large sample sizes have been conducted. Health promotion principles may be a starting point to develop effective population-based interventions. WHO defines health promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over their health and its determinants, and thereby improve their health.”17(p10) Health promotion is also defined by O'Donnell as “the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to move toward a state of optimal health,”18(p5) which includes physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health. Using these principles, mental health promotion will require a broad-based approach that fosters personal resilience within a supportive community environment. O'Donnell notes that creating a supportive environment might have the greatest lasting impact on optimal health.18 Addressing issues of racism and inequalities in housing, education, social justice, community safety, outlets for healthy food, and community participation may foster a more supportive community environment.19–21 Achieving these conditions will require that public health understand and address the social determinants of mental health.22 This focus may require social policy interventions at the community level to ensure equity in livable wages, safe housing and neighborhoods, attractive and safe places for physical activity, and access to affordable and healthy food. At the individual level, people need to be educated on the importance of positive mental health and well-managed mental illness, ways to cope in the face of adversity, and the role that mental health care shares with physical health care in helping them take control of their total health. Additionally, a comprehensive approach to address the social stigma of mental illness is needed. This approach should include nondiscriminatory policies that provide equal parity and reimbursement for mental illness treatment as well as educational programs and campaigns to better educate the public on mental illness. Stigma can affect the overall health, employment opportunities, and lack of social acceptance of those with mental illnesses.

THE CHARGE TO PUBLIC HEALTH

The 1999 surgeon general's report on mental health called for a broad public health approach that included not only clinical diagnosis and treatment of mental illness but also surveillance, research, and promotion of mental health.2,22 Furthermore, a recent workgroup of mental health experts, representing state health departments, academic institutions, professional organizations, community-based organizations, and federal agencies, suggested that new measures for mental health be developed and incorporated into national surveys.23 The group also suggested that more research should be conducted on the relationship between mental health and chronic diseases. This approach would suggest that surveillance data are needed to assess not only the prevalence of mental illness in the population but also the mental health status and its correlates in the population.

If public health is to meet the contemporary challenge of protecting and promoting the public's health, mental health promotion and protection must be incorporated into the overall goal of traditional treatment and risk model for health promotion. This approach requires the understanding that mental illness is a chronic disease that has a high rate of relapse and recurrence and is estimated to be second only to cardiovascular disease as a source of the global burden of disease by 2020.24 Therefore, the goal of total health for the population as a whole will require an integrated approach, with all health professionals working across disciplines, organizations, and health systems, including those addressing physical health and mental health and those encompassing primary care, mental health, and public health.19,22,25

References

- 1.Herman H, Saxena S, Moodie R, Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. A Report of the World Health Organization and Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration With the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Dept of Health and Human Services Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Preamble to the Constitution. New York, NY: International Health Conference; signed on July 22, 1946 (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2), entered into force on April 7, 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:207–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keyes CLM. Complete Mental health: an agenda for the 21st century. Keyes CLM, Haidt J. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walter EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A14 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/jan/04_0066.htm. Accessed May 02, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Dube SR, et al. The association of depression and anxiety with obesity and unhealthy behaviors among community-dwelling US adults. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strine TW, Chapman DP. Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health–related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Med. 2005;6(1):23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandeputte M, De Weerd A. Sleep disorders and depressive feelings. A global survey with the Beck depression scale. Sleep Med. 2003;4(4):343–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubzansky LD, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Kawachi I. Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and Coronary Heart Disease in the Normative Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:910–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyes CLM. Chronic physical conditions and aging: Is mental health a potential protective factor? Ageing Int. 2005;30(1):88–104 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danner DD, Snowdon DA, Friesen WV. Positive emotions in early life and longevity: findings from the Nun Study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(5):804–813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keyes CLM, Dhingra P, Simoes E. Change in level of positive mental health predicts risk of mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2366–2371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snowden M, Dhingra P, Keyes CLM, Anderson L. Is there a change in late-life mental well-being? Findings from MIDUS I and II. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2385–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truong KD, Ma S. A systematic review of relations between neighborhoods and mental health. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9(3):137–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(S1):10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donnell MP. Definition of health promotion: part III: expanding the definition. Am J Health Promot. 1989;3:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Primm AB, Vasquez MJT, Mays RA, et al. The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(1):A20 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0125.htm. Accessed May 27, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Dept of Health and Human Services (2001). Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satcher D, Druss BG. Bridging mental health and public health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(1):A03 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0133.htm. Accessed June 1, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giles WH, Collins JL. A shared worldview: mental health and public health at the crossroads. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(1):A02 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/ jan/09_0181.htm. Accessed June 3, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray JL, Lopez AD, Summary: The Global Burden of Disease. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sammons-Posey D, Guerrero R, Perry GS, Edwards VJ, White-Cooper S, Presley-Cantrell L. The role of state health departments in advancing a new mental health agenda. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(1):A06 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/ jan/09_0129.htm. Accessed June 2, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]