Abstract

This paper reports a new strategy based on plasma etching that allows us to exclusively probe the SERS-active molecules adsorbed in the hot-spot region formed between two Ag nanocubes. Experimentally, we verified that the enhancement factor of the hot spot (EFhot-spot) was strongly dependent on its orientation relative to the laser polarization. For the hot spot formed between two Ag nanocubes of 100 nm in edge length, the EFhot-spot was found to vary from 1.0×108 to 4.1×106 and 4.4×105 as the long axis of the dimer was changed from 0 (parallel) to 45 and 90 (perpendicular) degrees relative to the direction of laser polarization. These results suggest a maximum enhancement of Raman signals by ~170 folds for the hot spot relative to the EF obtained for a single Ag nanocube of similar size. While the hot spot made a major contribution to the observed SERS signals when the dimer's long axis was parallel to the laser polarization, the hot spot did not contribute additionally to the detected signals when the dimer was in other orientations relative to the laser polarization.

Keywords: SERS, hot spot, silver, nanocube, dimer

There has been a renewed interest in surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) following the demonstration of single-molecule detection with substrates made of Ag nanoparticles.[1, 2] In this system, it is thought that the giant enhancements that allowed for single-molecule detection did not occur homogeneously over the entire substrate. Instead, they occurred only at particular sites, the so-called hot spots.[3] Hot spots can be defined as junctions or gaps between two or more closely-spaced particles, in which enormous electromagnetic enhancements often arise as compared to individual particles.[4] The commonly used method for producing SERS substrates containing hot spots relies on the uncontrolled aggregation of Ag or Au nanoparticles as induced by a salt.[5] While these aggregates can provide strong SERS signals, the poor reproducibility on the fabrication as well as the broad size distribution and shape irregularity of the involved Ag nanoparticles imposes many challenges for correlating the detected scattering enhancement to the specific feature of a hot spot. Thus, although the hot-spot phenomenon has been extensively investigated from both theoretical and experimental perspectives, it still remains an elusive, feebly understood subject. In this regard, individual dimers of nanoparticles represent an ultimate system for quantitatively investigating the hot-spot phenomenon. At least, they would enable an easier correlation between specific hot-spot structures and the observed SERS intensities.[6–8] On the other hand, enhancements strong enough for ultrasensitive analysis and even single-molecule detection have been proposed for dimers consisting of Ag nanoparticles.[9] Despite these advantages, there are still limitations associated with the utilization of nanoparticle dimers for studying the hot spot. Due to the size and shape of the usually employed nanoparticles, SERS molecules absorbed inside and outside the hot-spot region can contribute to the detected SERS intensities.[6–9] As a result, the experimentally determined enhancement factor (EF) represents the average enhancement from the entire surface of the dimer. In this regard, determination of EFs exclusive from the hot-spot region still remains a great challenge.

In this paper, we describe a new strategy based on plasma etching for exclusively measuring the SERS signals from those molecules located in the hot-spot region formed between two Ag nanocubes. In this approach, the dimer of Ag nanocubes was functionalized with SERS probe molecules and then briefly exposed to plasma etching to selectively remove those molecules outside the hot-spot region. With the aid of registration marks, we were able to experimentally determine the SERS enhancement factor associated with the hot spot at different orientations relative to the laser polarization. To our knowledge, this work represents the first attempt to isolate the hot spot formed between two Ag nanoparticles, followed by measurements of the SERS enhancement factor intrinsic to a hot spot.

Figure S1 shows a typical SEM image of the sharp Ag nanocubes used in our SERS studies, which had an edge length of 100±5.7 nm. We chose them for a number of reasons. For example, they can be routinely synthesized with good uniformity in terms of shape and size distribution via the polyol method.[10] Their sharp corners and relatively large dimensions ensure that we will be able to obtain strong SERS signals as compared to smaller or rounded particles.[11] Also, they represent an ideal system for the isolation of the hot spot through plasma etching. We employed 4-methyl-benzenethiol (4-MBT) and 1,4-benzenedithiol (1,4-BDT) as the SERS probe molecules because they are known to form well-defined monolayers on Ag surfaces via a strong Ag-S linkage with characteristic molecular footprints. These attributes are critical to estimating the total number of molecules being probed and therefore the EF.[12] Moreover, these molecules are expected to be able to penetrate into the hot-spot region between two Ag nanocubes owing to their relatively small sizes.

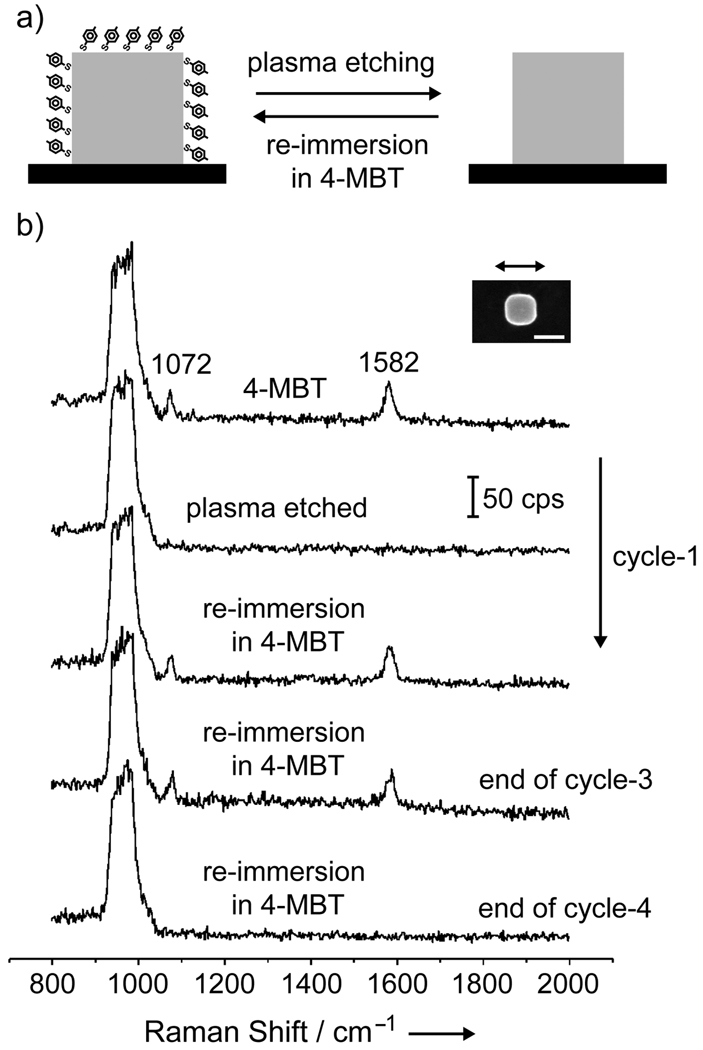

We started our measurements by investigating the effect of plasma etching on individual Ag nanocubes (Figure 1a). Specifically, we would like to know whether 4-MBT molecules adsorbed on the surface of a Ag nanocube could be removed by brief plasma etching. We were also interested in understanding if the plasma etching would lead to any physical and/or chemical changes to the Ag nanocube, including its capability to enhance the SERS signals from 4-MBT re-deposited on the Ag nanocube. Figure 1b shows a set of SERS spectra taken from the same Ag nanocube, which was functionalized with 4-MBT, plasma etched for 2 min, and then refunctionalized with 4-MBT by immersing into its solution. With the assistance of registration marks, we were able to locate the same Ag nanocube (see the inset) and take SERS spectra from it during these steps. We also repeated the cycle of functionalization, etching, and refunctionalization a number of times to see if plasma etching would eventually cause any irreversible change to the Ag surface. As clearly shown in Figure 1b, the initial spectrum (top trace) presents the characteristic SERS peaks for 4-MBT at 1072 and 1582 cm−1.[13] Here, the nanocube was oriented with one of its edges parallel to the laser polarization. The peak at 1072 cm−1 is due to a combination of the phenyl ring-breathing mode, CH in-plane bending, and CS stretching, while the peak at 1582 cm−1 can be assigned to phenyl ring stretching motion (8a vibrational mode).[14] The broad band at 900–1000 cm−1 came from the Si substrate. After the sample had been plasma etched for 2 min, both the 4-MBT peaks disappeared from the SERS spectrum (second trace from the top), indicating complete removal of the 4-MBT molecules from the surface of the nanocube. Interestingly, both peaks of 4-MBT appeared again in the SERS spectrum (third trace from the top) after the etched sample had been re-immersed in the 4-MBT solution. No significant change was observed for the SERS peaks of 4-MBT when the first and third spectra were compared. This result suggests that the number of 4-MBT molecules that were re-deposited on the Ag nanocube after plasma etching was essentially the same as the number of molecules initially adsorbed on the Ag nanocube. It also implies that plasma etching merely removes the 4-MBT molecules from the surface of the Ag nanocube when the exposure time is relatively short. The complete cycle comprising of plasma etching and re-immersion in 4-MBT could be repeated up to three times without observing major deterioration in the SERS spectrum. However, after the fourth cycle, no 4-MBT peaks could be detected. It is possible that surface oxidation after an extended exposure to the oxygen-based plasma will hamper the adsorption of 4-MBT onto the surface.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the approach employed for removal and functionalization of a single Ag nanocube with 4-MBT via plasma etching and re-immersion in a 4-MBT solution. (b) SERS spectra from a single Ag nanocube functionalized with 4-MBT, followed by successive cycles of plasma etching and re-immersion in 4-MBT (from top to bottom, respectively). The exchange process could occur up to three cycles of plasma etching and re-immersion in 4-MBT solution. After the fourth round of plasma etching, the Ag nanocubes could not be re-functionalized with 4-MBT any further. The SEM image in the inset was taken after the fourth round of plasma etching; the slight truncation at corners is probably due to surface oxidation under extended exposure to the oxygen-plasma. The scale bar in the inset corresponds to 100 nm.

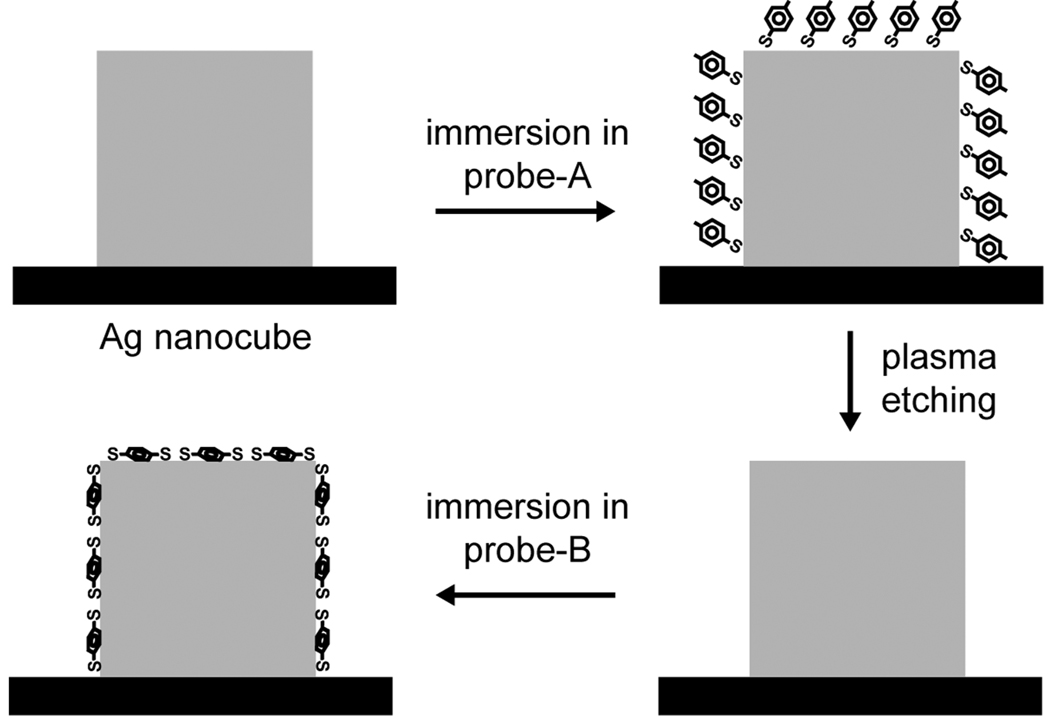

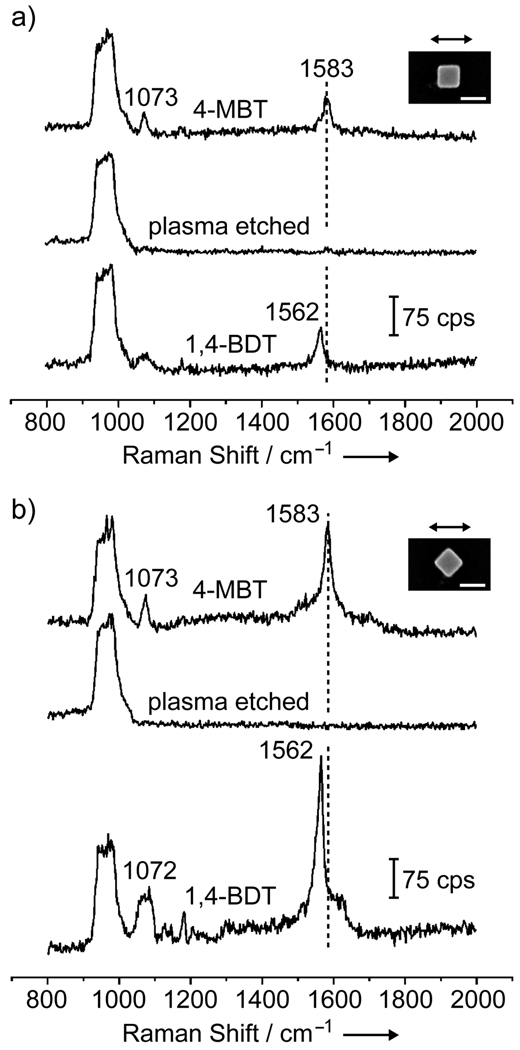

The plasma etching could also be employed to change the probe molecules adsorbed on the surface of an individual Ag nanocube. This concept is illustrated in Figure 2. In the first step, the nanocube is functionalized with 4-MBT (probe-A). Then, the probe-A molecules are removed by briefly subjecting the sample to plasma etching. Finally, the sample is immersed in a solution containing 1,4-BDT (probe-B). Figure 3 shows the SERS spectra recorded from a sample going through these steps. In Figure 3a, the nanocube was oriented with one of its edges parallel to the laser polarization. The initial spectrum (top trace) presents the characteristic peaks for 4-MBT at 1073 and 1583 cm−1,[13] which completely disappeared after plasma etching (middle trace). After immersion in a 1,4-BDT solution, the characteristic peaks for 1,4-BDT appeared in the SERS spectrum as a result of the adsorption of 1,4-BDT onto the nanocube. In this case, we observed a shift in phenyl ring stretching motion band (8a mode) from 1582 cm−1 (for 4-MBT) to 1562 cm−1 (for 1,4-BDT).[15] The same trend was also observed when the nanocube was orientated with one of its face diagonals parallel to the laser polarization, as shown in Figure 3b. In this case, the intensities of the SERS signals were much stronger as compared to those in Figure 3a. As previously reported by our group, the SERS signals taken from a single Ag nanocube had a strong dependence on the laser polarization, which could be attributed to the difference in near-field distribution over the surface of a nanocube under different polarization directions.[16] In addition to the shift in position for the 8a band from 1583 to 1562 cm−1, broadening was observed for the band at 1072 cm−1 for 1,4-BDT as compared to 4-MBT. This is because the ordinary Raman spectrum of 1,4-BDT displays two bands in this region (1080 and 1065 cm−1), which tend to broaden and overlap in the SERS spectrum due to interactions between the Ag surface and the π-orbital system of the benzene ring.[15] The SERS spectrum for 1,4-BDT also displayed a weak signal at 1180 cm−1 that could be assigned to the 9a vibrational mode (CH bending).[15]

Figure 2.

Schematic of the approach employed for the exchange between 4-MBT (probe-A) and 1,4-BDT (probe-B) on a single Ag nanocube. The Ag nanocube is functionalized with probe-A and then exposed to plasma etching to remove the absorbed probe-A molecules from the surface of the nanocube. In the next step, the nanocube is immersed in a solution of probe-B molecules. As 4-MBT and 1,4-BDT present different Raman signatures, the exchange process can be readily monitored by observing the shift in the 8a band (1550–1600 cm−1) for the benzene ring.

Figure 3.

SERS spectra from a single Ag nanocube functionalized with 4-MBT (top trace), followed by plasma etching for 2 min (middle), and immersion in a 1,4-BDT solution (bottom). In (a) and (b), the laser was polarized along an edge and a face diagonal of the Ag nanocube, respectively. The scale bar in the inset corresponds to 100 nm.

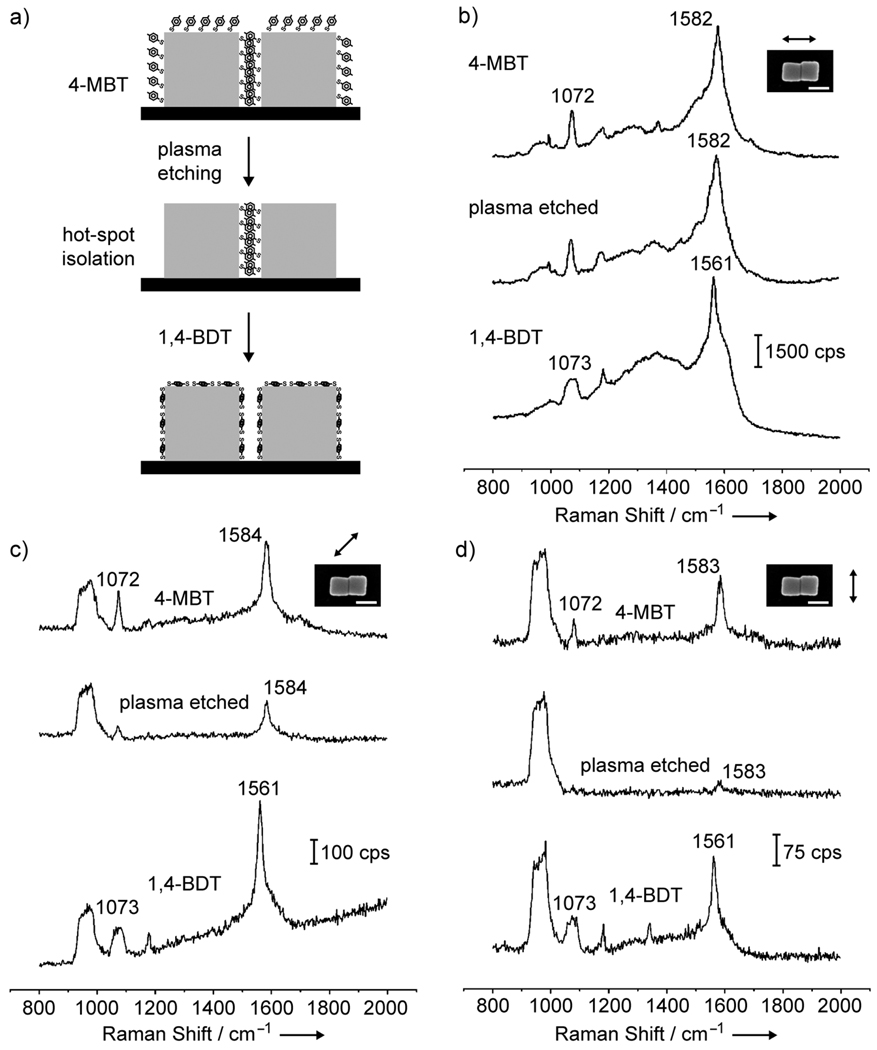

After the experimental details for surface functionalization and plasma etching had been established for individual Ag nanocubes, we turned our attention to dimers of Ag nanocubes. In this case, we aimed at isolating the 4-MBT molecules located in the hot-spot region by exposing the sample to plasma etching under similar conditions as employed for the individual nanocubes. It is important to note that under the conditions used in this work, both 4-MBT and 1,4-BDT are expected to be present on the Ag surface as a complete monolayer. Therefore, for individual Ag nanocubes, the plasma etching was responsible for the removal of a 4-MBT monolayer adsorbed on the Ag surface. Similarly, for nanocube dimers, the plasma etching is expected to remove a monolayer of 4-MBT molecules present on the surface. As the hot-spot region in the nanocube dimers comprises a narrow gap between two nearly touching nanocubes, the 4-MBT molecules in the hot spot can be considered as a multilayer resist relative to the oxygen plasma (Fig. 4a). If each 4-MBT molecule has a 0.19 nm2 footprint, each 4-MBT molecule can be assumed to occupy a circular area of 0.249 nm in diameter on the Ag surface. As the nanocubes have an edge length of 100 nm, approximately 400 layers of 4-MBT molecules can be present in the hot-spot region along the vertical direction. Therefore, it will require a much longer time to remove the 4-MBT molecules located in the hot spot as compared to those molecules outside the hot-spot region. This scenario explains why plasma etching can serve as an effective method for isolating the hot spot formed between two Ag nanocubes. In order to demonstrate that no significant change took place on the surface of the nanocube dimers during plasma etching, the sample was also immersed in a 1,4-BDT solution after the hot spot had been isolated.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic of the approach employed for probing the hot spot formed in a dimer of Ag nanocubes. The dimer was functionalized with 4-MBT and then exposed to plasma etching to remove the adsorbed 4-MBT molecules. In this case, only the 4-MBT molecules outside the hotspot region (i.e., outside the two touching faces) were removed during the plasma etching. The nanocube dimer was then immersed in a 1,4-BDT solution, resulting in the complete replacement of 4-MBT by 1,4-BDT over its entire surface. (b–d) SERS spectra from a Ag nanocube dimmer functionalized with 4-MBT (top), followed by after plasma etching for 2 min (middle) and then immersion in a 1,4-BDT solution (bottom). The laser was polarized at 0, 45 and 90 degrees with respect to the long axis of the dimer. The scale bars in the insets correspond to 100 nm.

Figure 4, b–d, shows the SERS spectra from a nanocube dimer that was functionalized with 4-MBT (top trace), followed by plasma etching for 2 min (middle trace) and then immersion in a 1,4-BDT solution (bottom trace). In Figure 4b, the long axis of the dimer was parallel to the laser polarization. The SERS spectrum from the Ag nanocube dimer functionalized with 4-MBT clearly showed the characteristic peaks for 4-MBT at 1072 and 1582 cm−1.[13,14] The much stronger intensity of the SERS signals as compared to Figures 1b and 3a reflects a higher SERS activity for the dimer relative to the individual nanocubes due to the presence of a hot spot. We employed the peak at 1582 cm−1 to estimate the EF as described in the supporting information. Based on our assumptions, the EF for the initial nanocube dimer (EFdimer) functionalized with 4-MBT (Figure 4b, top trace) was 2.2×107. In comparison, the EF calculated for an individual Ag nanocube (EFcube) under the same polarization (Figure 3a, top trace) was 5.9×105. This indicates that the EFdimer was ~37 times higher than EFcube. After plasma etching (Figure 4b, middle trace), a slight decrease in the intensity was observed for the 4-MBT bands at 1072 and 1582 cm−1. This slight reduction due to the removal of 4-MBT molecules from the region outside the hot-spot region indicates that the molecules in the hot spot were the major contributors to the SERS signals from the dimer. By assuming that only the 4-MBT molecules adsorbed in the hot-spot region were present in the nanocube dimer after plasma etching, the calculated EF for the hot-spot (EFhot-spot) was 1.0×108. In this case, EFhot-spot was higher than EFdimer and EFcube by a factor of 4.5 and 170, respectively. After the sample was immersed in a 1,4-BDT solution, all the peaks due to 4-MBT were replaced by the characteristic peaks of 1,4-BDT (Figure 4b, bottom trace), as it can be observed from the shifting of the 8a band to 1561 cm−1 and the broadening of the 1073 cm−1 peak. This result indicates that, in addition to be adsorbed onto the faces of the nanocubes outside the hot spot, 1,4-BDT replaced the 4-MBT molecules in the hot-spot region. The stronger interaction between 1,4-BDT and Ag than 4-MBT and Ag may provide the driving force for this process (Figure S2 and S3).[13–15,17] After complete replacement of 4-MBT by 1,4-BDT, EFdimer was 1.9×107, which is close to the initial EFdimer obtained with 4-MBT, indicating that no significant change on the surface of the nanocube dimers occurred as a result of plasma etching.

Figure 4c illustrates the SERS spectra from the nanocube dimer in which the long axis of the dimer was at 45° relative to the laser polarization. The SERS signals were weaker compared to those in the spectra shown in Figure 4b as a result of inferior SERS activities under this configuration. The initial spectrum for the nanocube dimer presents the characteristic peaks for 4-MBT. EFdimer was calculated as 2.0×106, representing a 11-fold decrease as compared to the EFdimer calculated from Figure 4b. Comparatively, when the individual nanocube was orientated with a face diagonal parallel to the laser polarization (Fig. 3b, top trace), EFcube was 2.3×106. The fact that EFdimer is close to EFcube under this configuration suggests that the molecules in the hot-spot did not contribute additionally towards the SERS signals observed for the dimer. This is also confirmed by inspecting the SERS spectrum after plasma etching (Fig. 4c, middle trace). In this case, a significant decrease in intensity for both the 1072 and 1584 cm−1 peaks were observed as the 4-MBT molecules were removed from the region outside the hot spot. EFhot-spot was calculated to be 4.1×106, indicating that EFhot-spot is within the same order of magnitude as EFdimer and EFcube. After the sample was immersed in a 1,4-BDT solution, all the peaks due to 4-MBT were replaced by the characteristic peaks of 1,4-BDT (Fig. 4c, bottom trace) and EFdimer was calculated as 1.6×106, which agrees with the initial EFdimer obtained with 4-MBT.

Figure 4d shows the SERS spectra for which the long axis of the dimer was perpendicular to the laser polarization direction. In this case, the SERS signals further decreased in comparison to Figure 4c, and were much weaker relative to Figure 4b. EFdimer was calculated as 6.8×105, which is close to the value of 5.9×105 obtained for single Ag nanocubes (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the molecules in the hot spot did not make any additional contribution toward SERS signals observed for the dimer. After plasma etching, while the peak at 1072 cm−1 completely disappeared, the peak at 1583 cm−1 became very weak and EFhot-spot became 4.4×105, which was on the same order of magnitude as EFdimer and EFcube. After immersion in 1,4-BDT, all the 4-MBT were replaced by the characteristic peaks of 1,4-BDT and EFdimer was found to be 5.4×105.

According to near-field calculations by the discrete-dipole approximation (DDA) method for Ag nanocubes 100 nm in size at 514 nm excitation,[16] the near-field distribution is expected to be concentrated on the faces that form the hot-spot region when the laser polarization is parallel to the dimer long axis. This could lead to a SERS enhancement of 170 folds stronger for EFhot-spot as compared to EFcube. However, when the long axis of the dimer is at 45° and 90° relative to the laser polarization direction, the near-field distributions are expected to be mostly concentrated outside the hot-spot region, i.e., at the corners and on the faces that are perpendicular to the dimer's long axis, respectively. This reduction of near-field distribution in the hot-spot region can be considered to be responsible for the significant decrease in the EFhot-spot when the long axis of the dimer is at 45° and 90° relative to the laser polarization.

In summary, we have demonstrated a simple and versatile approach based on plasma etching for isolating and exclusively probing the hot spot in a dimer of Ag nanocubes. In this approach, the dimer of Ag nanocubes was first functionalized with 4-MBT and the hot spot was then isolated by exposing the sample to plasma etching. The plasma etching only led to the removal of molecules adsorbed on the surface outside the hot-spot region. Finally, the sample was functionalized with 1,4-BDT to demonstrate that the surface of the dimer did not undergo any significant changes during plasma etching. Based on this approach, EFhot-spot was calculated as 1.0×108, 4.1×106, and 4.4×105 as the long axis of the dimer was oriented at 0 (parallel), 45, and 90 (perpendicular) degrees relative to the laser polarization, respectively. Likewise, EFdimer (without isolating the hot spot) was calculated as 2.2×107, 2.0×106 and 6.8×105, respectively. These results indicate that EFhot-spot displayed a strong dependence on the laser polarization, experiencing an increase by a factor of ca. 10 and 230 as the long axis of the dimer was rotated from 90 to 45 degrees and from 90 to 0 (relative to the laser polarization). Similarly, EFdimer displayed an increase by a factor of ca. 3 and 30. By comparing EFhot-spot with EFcube, EFhot-spot was increased by ca. 170 folds when the dimer's long axis was parallel to the direction of laser polarization.

Experimental Section

The Ag nanocubes were synthesized according to our previously reported procedures.[10] Samples for correlated SEM and SERS experiments were prepared by drop-casting an ethanol suspension of the Ag nanocubes on a Si substrate that had been patterned with registration marks and letting it dry under ambient conditions. In this case, dimers could form spontaneously via aggregation during solvent evaporation. Functionalization with 4-methyl-benzenethiol (4-MBT, Aldrich) or 1,4-benzenedithiol (1,4-BDT, Aldrich) was performed by immersing the substrate containing Ag nanocubes in a 5 mM ethanol solution (5 mL) of 4-MBT or 1,4-BDT, respectively, for 1 h. The sample was then taken out, washed with copious amounts of ethanol, and finally dried under a stream of nitrogen. The plasma etching was performed in a plasma cleaner/sterilizer (Harrick Scientific Corp., PDC-001) operated at 60 Hz and 0.2 Torr of air, with power being set to high. Plasma etching of the sample was performed by placing the Si substrate containing the Ag particles in the plasma cleaner chamber and exposing it to the oxygen plasma for 2 min. Since plasma etching is highly sensitive to many parameters, one needs to at least optimize the etching time and air pressure when this protocol is applied to a specific system. All samples were used immediately for SERS measurements after preparation. The SERS spectra for individual Ag nanocubes and dimers were monitored following each step of functionalization and plasma etching.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the NSF (DMR-0804088) and a 2006 Director’s Pioneer Award from the NIH (5DP1OD000798). P.H.C.C. was supported in part by the Fulbright Program and the Brazilian Ministry of Education (CAPES).

References

- 1.a) Nie S, Emory SR. Sience. 1997;275:1102. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kneipp K, Wang Y, Kneipp H, Perelman LT, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:1667. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recent reviews: Pieczonka NPW, Aroca RF. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:946. doi: 10.1039/b709739p. Stiles PL, Dieringer JA, Shah NL, Van Duyne RP. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008;1:601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112814. Willets KA, Van Duyne RP. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2007;58:267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104607. Kneipp K, Kneipp H, Kneipp J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:443. doi: 10.1021/ar050107x.

- 3.a) Otto A. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2006;37:937. [Google Scholar]; b) Le Ru EC, Etchegoin PG, Meyer M. J. Phys. Chem. 2006;125:104701. doi: 10.1063/1.2360270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Doering WE, Nie S. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:311. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Le Ru EC, Meyer M, Blackie E, Etchegoin PG. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2008;39:1127. [Google Scholar]; b) Le Ru EC, Blackie E, Meyer M, Etchegoin PG. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:13794. [Google Scholar]; c) Wang Z, Pan S, Kraus TD, Du H, Rotheberg LJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133217100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Otto A. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2002;33:593. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kneipp K, Kneipp H, Itzkan I, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2957. doi: 10.1021/cr980133r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Olk P, Renger J, Härtling T, Wenzel MT, Eng LM. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1736. doi: 10.1021/nl070727m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Svedberg F, Li Z, Xu H, Käll M. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2659. doi: 10.1021/nl062101m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Talley CE, Jackson JB, Oubre C, Grady NK, Hollars CW, Lane SM, Huser TR, Nordlander P, Halas NJ. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1569. doi: 10.1021/nl050928v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brandl DW, Oubre C, Nordlander P. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:024701. doi: 10.1063/1.1949169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang H, Halas NJ. Nano Lett. 2005;6:2945. doi: 10.1021/nl062346z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Camargo PHC, Lu X, Xia Y. Nano Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1021/nl803621x. ASAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camden JP, Dieringer JA, Wang Y, Masiello DJ, Marks LD, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12616. doi: 10.1021/ja8051427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Skrabalak SE, Au L, Li X, Xia Y. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2182. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Im SH, Lee YT, Wiley B, Xia Y. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:2192. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:2154. [Google Scholar]; c) Sun Y, Xia Y. Science. 2002;298:2176. doi: 10.1126/science.1077229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) McLellan JM, Siekkinen A, Chen J, Xia Y. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006;427:122. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hao E, Schatz GC. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:357. doi: 10.1063/1.1629280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFarland AD, Young MA, Dieringer JA, Van Duyne RP. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:11279. doi: 10.1021/jp050508u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Khan MA, Hogan TP, Shanker S. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2008;39:893. [Google Scholar]; b) Sauer G, Brehm G, Schneider S. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2004;35:568. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Osawa M, Matsuda N, Yoshii K, Uchida I. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:12702. [Google Scholar]; b) Gui JY, Stern DA, Frank DG, Lu F, Zapien DC, Hubbard AT. Langmuir. 1991;7:955. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Joo SW, Han SW, Kim K. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;240:391. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2001.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cho SH, Han HS, Jang D-J, Kim K, Kim MS. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:10594. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan JM, Li Z-Y, Siekkinen AR, Xia Y. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1013. doi: 10.1021/nl070157q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo K, Borguet E. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:6335. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.