Abstract

Recently, Sazanov’s group reported the X-ray structure of whole complex I [Nature, 465, 441 (2010)], which presented a strong clue for a “piston-like” structure as a key element in an “indirect” proton pump. We have studied the NuoL subunit which has a high sequence similarity to Na+/H+ antiporters, as do the NuoM and N subunits. We constructed 27 site-directed NuoL mutants. Our data suggest that the H+/e− stoichiometry seems to have decreased from (4H+/2e−) in the wild-type to approximately (3H+/2e−) in NuoL mutants. We propose a revised hypothesis that each of the “direct” and the “indirect” proton pumps transports 2H+ per 2e−.

Keywords: NADH-quinone oxidoreductase, Complex I, SQNf-gated “direct” proton pump, QNs-induced “indirect” proton pump, Conformationally-driven H+ pump

1. Introduction

NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is located at the entry point of the respiratory chain in both mitochondria and bacteria. It catalyzes transfer of two electrons from NADH to quinone (Q) pool. Coupled with this exergonic electron transfer reaction, about four protons (current consensus value) are transported across the mitochondrial inner membrane or bacterial cytoplasmic membrane to generate the proton electrochemical potential with a 4H+/2e− stoichiometry, which drives ATP synthesis [1,2]. It should be pointed out that two scalar protons are simultaneously taken up from the negative side of the energy converting membrane, and transfer two protons to the quinone pool. The bovine heart complex I has a molecular weight close to 980 kDa, consisting of 45 dissimilar protein subunits [3]. Bacterial complex I has a smaller molecular weight (~500 kDa) made of 13–14 subunits [4] (In Escherichia coli complex I, NuoC and NuoD subunits are fused together). The total number and general physicochemical properties of prosthetic groups are similar to the mitochondrial counterparts. Therefore, bacterial complex I is useful as a minimal model of mitochondrial complex I.

Both eukaryotic and prokaryotic complex I molecules have a unique L-shape, composed of almost equally sized intra- and extra- membrane parts [5,6]. The extra-membrane part contains all prosthetic groups, one non-covalently bound FMN, 8 iron-sulfur (Fe/S) clusters (some bacteria contain one extra Fe/S cluster) [7,8].

The proton translocation takes place in the membrane spanning domain of complex I [9,10], where no prosthetic groups are located [11–13], except for two protein-associated QNf and QNs molecules [7,14,15]. Binding sites of these Q species [16–19] and of many complex I inhibitors are localized in the intra-membrane domains [20,21] close to the locus surrounded by the NuoD/49 kDa, NuoB/PSST, NuoH/ND1, and NuoN/ND2 subunits (E. coli/human complex I subunit nomenclature)2. Sequence changes in this area correlate with many human diseases [22] indicating that this is one of the most important locations in complex I. Extensive studies have been conducted for NuoD and NuoB [23,24], NuoH [20,21,25] and NuoN [19,26] subunits.

In 2006, Sazanov and Hinchliffe reported the X-ray crystal structure of hydrophilic extra-membrane domain of Thermus thermophilus HB-8 at 3.3 Å resolution [11]. This confirmed the total number of flavin and Fe/S clusters predicted by EPR [7] and revealed a long line (~95 Å) of the major electron transfer pathway; NAD→FMN-N3-N1b-N4-N5-N6a/b-N2→Q. Another Fe/S cluster N1a has a lower Em value than the substrate couple (NADH/NAD+) and is localized on the other side of the major respiratory chain. It may have an antioxidant function for the semiflavin site [11].

Ohnishi and her collaborators characterized previously two distinct protein-associated semiquinone (SQ) species in the NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) segment of the respiratory chain [7,14]. They are designated as fast-relaxing semiquinone species (SQNf) and slow-relaxing semiquinone species (SQNs). The signal intensity of SQNf is dependent on the poised proton electrochemical potential , while that of SQNs is not. Based on a detailed analysis of the direct spin–spin interaction between reduced cluster N2 and SQNf, their mutual center-to-center distance was calculated as 12 Å. The projection of the N2-SQNf vector along the membrane normal was found to be only 5 Å [27]. Therefore, Ohnishi and Salerno proposed a directly quinone-coupled, SQNf-gated proton pumping mechanism [28].

This “direct” proton pump hypothesis was revised to include both SQNf and SQNs molecules. The proton transport machineries must be located in the membrane spanning domain of complex I. Thus, we attempted to answer this tough question in complex I, namely, how these two different functions can be coupled with each other. This is a new “chimera model” in which the “direct” SQNf-gated proton pump transports 2H+ and the “indirect” SQNs-induced proton pump transports 2H+ [29].

Recently, Sazanov’s group reported a long-awaited first X-ray structure of the membrane part of E. coli complex I at 3.9 Å resolution and the whole complex I of T. thermophilus at 4.5 Å resolution [30]. They found that the largest NuoL, NuoM and NuoN subunits have Na+/H+ antiporter-like structures. Surprisingly, they found that the NuoL subunit differs in an important aspect from NuoM and NuoN subunits: it has an unusually long amphipathic α-helix, which runs parallel to the membrane extending close to the bound Q and electron transfer chain. Therefore, they proposed a unique “piston-like” mechanism for proton pumping by complex I in which this long, horizontal α-helix acts as a “connecting rod” that can simultaneously open and close channels of antiporter homolog subunits, NuoL, NuoM, and NuoN.

Their paper presented the first structural clue regarding the mechanism of indirect pump. It will lead to the new development of structure/function relationship in complex I as explained by Ohnishi in the News and view of the same issue of nature [31].

Using site-specific mutagenesis approaches, we have obtained the first experimental evidence which indicates the “indirect” coupling mechanism in the NuoL subunit. This will be briefly presented in this paper.

We hope that our new “chimera” model, which is different from any of the previously published models, will illuminate the new mechanistic details of energy coupling in complex I3.

2. Result

2.1. Our mutagenesis study on the possible “indirect” proton pumping mechanism in the NuoL subunit

Three large intra-membrane subunits of complex I (NuoL, NuoM, and NuoN) have a high similarity of the primary sequence among each other [12,13], and between complex I and multi-subunit Na+/H+ antiporters [32,33]. Thus, their involvement in the “indirect” proton pump has been the subject of speculation for some time. Although NuoL subunit was shown to be located at the far end of the membrane arm of complex I, this was photo-affinity-labeled by the potent complex I inhibitor fenpyroximate, and the electron transfer activity was simultaneously inhibited with the labeling. In addition, this labeling was completely blocked by the pretreatment with rotenone and piericidin A, both of which are well known to bind to the Q-binding sites [17,18]. We focused on this enigmatic NuoL subunit which was the only remaining subunit not investigated by site-directed mutagenesis approach [33,34–36].

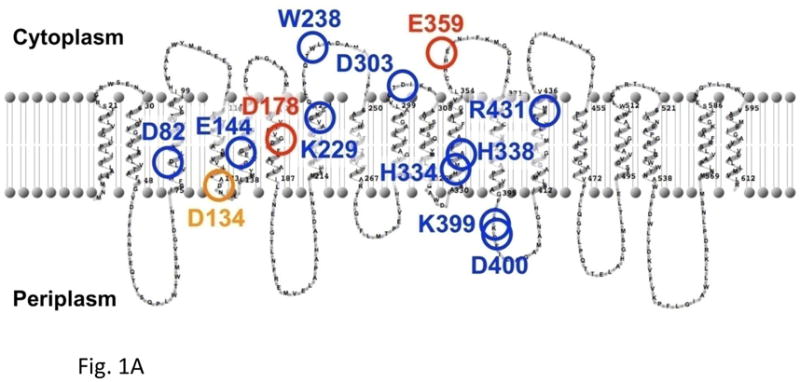

Fig. 1A shows a secondary structure model of NuoL subunit of E. coli complex I, predicted by using TMHMM and TopPred software which correspond reasonably well to the structure determined by cryo-electron microscopy at 8 Å resolution [32]. We have selected 13 highly conserved amino acid residues in E. coli NuoL subunit. Blue circles are mutated amino acid residues which are conserved between NuoL and MrpA of multi-subunit monovalent cation antiporters. Red are conserved only within the complex I family. Orange is conserved in complex I from bacteria and plants, and MrpA of multi-subunit cation antiporters. Since these residues could thus be involved in the proton transfer activities, we constructed 27 site-directed NuoL point mutants to investigate their roles.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1A. The secondary structure model of the E. coli NuoL/ND5 subunit, and putative locations of the mutated amino acids in this study. Blue circles: conserved amino acid residues in NuoL/ND5 of complex I, and MrpA of multi-subunit cation antiporters. Red circles: conserved amino acid residues only in NuoL/ND5 of complex I. Orange circles: conserved amino acid residues in NuoL/ND5 of complex I from bacteria and plants, and MrpA of multi-subunit cation antiporters. These marked amino acid residues are likely to be involved in the “indirect” proton pump. All descriptions are in the text. It is interesting to point out in this secondary structure model that the long “piston” like amphipathic α-helix appears to be represented as two membrane spanning helices, residues 521–586.

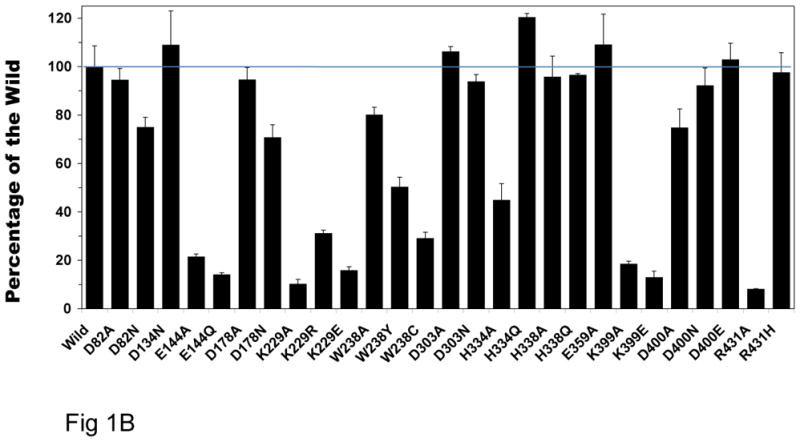

Fig. 1B. Deamino-NADH oxidase activities of wild-type and all 27 NuoL site-specific mutants. The dNADH oxidase activity assays were performed spectrophotometrically at 37 °C with 50 μg/ml of membrane samples in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA. The reaction was started by the addition of 0.15 mM dNADH, and the measurements were followed at a wavelength of 340 nm. Percent activity of all mutants were shown using the wild-type as a control (852 nmol dNADH oxidation min−1 mg−1).

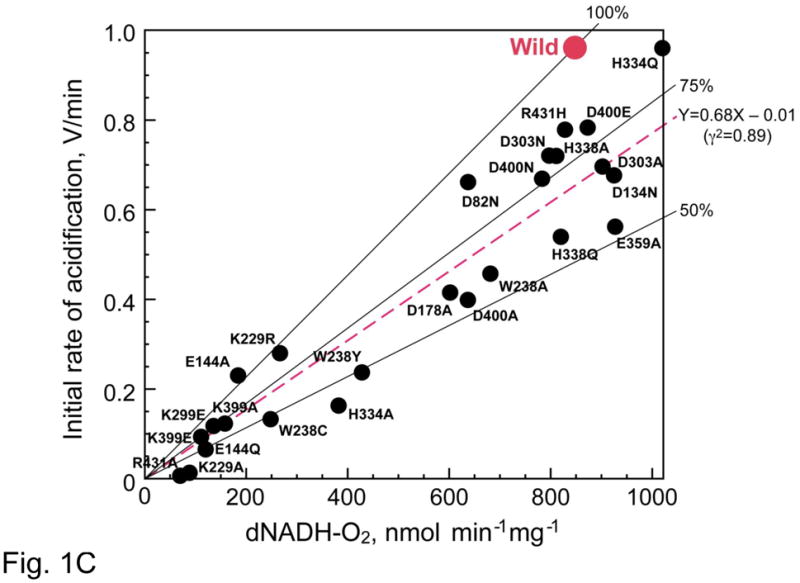

Fig. 1C. Linear regression analysis of the entire data. Proton pump activity was measured at 30 °C by acridine orange (AO, ex = 493 nm, em = 530 nm) fluorescence quenching in 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 5 μM AO as described in Ref. [45]. If we assign the wild (red spot) is situated at X = 1 and Y = 1, all mutants data can be expressed by Y = 0.68X − 0.01. The mutations caused the relative proton pumping efficiency decrease to 68%. This value is close to 75% which suggests that the proton pumping stoichiometry is decreased from the wild-type (4H+/2e−) to (3H+/2e−) by the mutations of NuoL/ND5.

In E. coli there are two different NADH-Q reductases, one is the counterpart of mitochondrial complex I and the other is an alternative non-energy converting enzyme. For simplicity, we call the former enzyme as E. coli complex I. We can specifically measure its activity using deamino-NADH (dNADH) which is not oxidized by the other enzyme [37] as a substrate.

This study provides the first experimental evidence for the function of the “indirect” coupling mechanism in complex I. This was achieved by the use of all site-directed NuoL mutants and utilizing a specific proton transport inhibitor, 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), as presented in Table 1, which will be described later part of the text.

Table 1.

Effect of EIPA on the initial rate of H+ transfer/dNADH-O2 activity of E. coli complex I Wild D178N

| EIPA 50 μM | Wild |

D178N |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | − | + | |

| Initial rate (V/ml) | 0.964 ± 0.085 100% | 0.603 ± 0.05a) 62.6% | 0.458 ± 0.01b) 47.5% | 0.45 ± 0.09c) 46.6% |

| dNADH-O2 activity (nmol/min/mg) | 913 ± 24.5 100% | 863 ± 48.6d) 94.5% | 630 ± 51.8e) 69.0% | 568 ± 26.2f) 62.2% |

Data is expressed in means ± S.D. from 3 to 6 measurements. Significance of difference in the initial rate of acidification: the effects of EIPA on the wild-type acidification is significant (P < 0.01) as shown by the control and (a). The wild-type and mutants (b and c) are significant (p < 0.01) for both ±EIPA; effect of EIPA on the mutant is insignificant difference (between (b) and (c)). Significance of difference in the respiration: effect of EIPA in the wild-type (the control and (d)) is not significant; the difference between wild-type and mutants (e and f) are significant with P < 0.01. The effects of EIPA on the mutants (between (e) and (f)) were not significant.

Fig. 1B shows dNADH oxidase activity of complex I using membrane vesicles prepared from wild-type and all 27 NuoL mutant membranes. These mutants were constructed by chromosomal homologous recombination following the modified method reported by Kao et al. [38]. Percent activity of all mutants was shown relative to the wild-type. dNADH oxidase activity of E144, K229, K399 mutants showed drastically decreased to 10–30% of the wild-type.

In order to investigate whether mutation in NuoL affects the subunit assembly of complex I, each membrane suspension was subjected to SDS–PAGE using the discontinuous system of Laemmli [39]. The expression of the E. coli complex I subunits was immunochemically determined by using antibodies specific to NuoB and to an oligopeptide (EcoNuoL-1) synthesized for NuoL subunit. Western blot analysis of blue native gel electrophoresis [40,41] showed that in these mutants the amount of the assembled complex I was significantly decreased. There are 14 mutant membranes in which complex I was fully assembled. However, even among those mutants, mutation still had strong effects on the activity and tightness of assembly. For example, three site-specific mutants (W238A, W238Y, W238C) and two (R431H and R431A) mutants show quite different subunit assembly and activities.

To compare proton pumping efficiency of the wild-type and NuoL mutants, we measured uncoupler sensitive dNADH oxidase reaction of E. coli membrane vesicle preparations. We measured the proton pumping activity of complex I in the presence of exogenous Q (decylubiquinone) as an electron acceptor and 5 mM KCN, which inhibits the bo3 oxidase that exists in the downstream of the E. coli respiratory chain. We confirmed that H+ pumping activity of cytochrome bo3 in NuoL mutants was unchanged. By simultaneously testing the H+ pumping activity in the succinate → cytochrome bo3 oxidation activity, no change was seen in NuoL mutants. To compare the proton pumping activity among mutants more quantitatively, the concentration of membrane vesicles was set to 50 μg/ml. Up to this concentration, both the initial acidification rate (initial proton pumping rate) and dNADH oxidation rate change linearly with the protein concentration. In order to analyze the accurate relationship between the relative proton pumping efficiency of wild-type and all NuoL mutants, we analyzed the relationship between initial acidification rate and electron transfer rates of both wild-type and all NuoL mutants.4

Fig. 1C shows the relative proton pumping efficiency of all 27 homologous mutagenesis samples relative to the wild-type. The ordinate stands for the initial proton transport activity and the abscissa for the electron transfer activity. The location of the wildtype is assigned for the location of (X = 1, and Y = 1) for the sake of simplicity. If a mutant loses both respiration and proton transport in the same degree, then, the proton stoichiometry will still be the same, and the location of that mutant on this chart is on the line connecting between the origin and (X = 1 and Y = 1). In other words, how much a mutant lost the proton transport below the stoichiometry of (4H+/2e−) is shown by the position of the mutant below this line. As shown in the figure, all mutant samples had a lower efficiency than the wild-type. The linear regression analysis revealed that the position of all mutants can be expressed by the equation of

where the correlation coefficient r = 0.94.

The value of the slope is 0.68. This is closer to 0.75 (i.e., 3H+/2e−) rather than 0.50 (2H+/2e+). Therefore, the proton stoichiometry of (4H+/2e−) in the wild-type seems to have decreased to (3H+/2e−) by the mutation in NuoL. As mentioned earlier, proton pumping efficiency of most mutants seem to be related to the tightness of the NuoL subunit assembly. Although the high correlation coefficient seems to indicate a quite good fit by the linear regression, we should apply the same approach to the NuoM subunit, and confirm that similar result would be obtained by the mutagenesis for NuoM subunit.

Here we would like to show an excellent application of a specific proton transfer inhibitor, EIPA, to further support the indirect proton pumping reaction occurring in the NuoL subunit.

Amiloride derivative, EIPA, was known as a specific inhibitor of K+ or Na+/H+ antiporters and can also inhibit electron transport activity of complex I. Nakamaru-Ogiso et al. found it as an inhibitor of proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of bovine heart SMP with the same effective concentration as that of the Na+/H+ antiporters [17,18]. However, electron transfer activity of E. coli complex I was found to be much less sensitive (IC50 >100 μM) [17]. However, it was recently discovered by Nakamaru- Ogiso (unpublished finding) that proton transfer activity is much more sensitive to EIPA. At 50 μM, maximal inhibition was obtained, but electron transfer was not inhibited even up to 100 μM. Similar observation was reported by Dlaskova et al. that in rat liver mitochondrial system, proton transfer activity is much more sensitive to EIPA than the electron transfer activity [42]. Therefore, amiloride is considered to be primarily a specific H+ pump inhibitor for complex I, which turns out to be very beneficial for our study of “indirect” coupling mechanism in E. coli NuoL subunit.

Table 1 shows the effect of antiporter inhibitor, EIPA on the initial rate of proton transfer (acidification) and dNADH respiration of wild-type and NuoL mutant D178N. In this example, the initial rate of acidification of the wild-type was inhibited by about 37% by EIPA, while that of D178N was already inhibited to about a half by the NuoL mutation. EIPA has no effect on the proton transfer of the mutant, suggesting that indirect proton transport had been already inhibited by the NuoL mutagenesis. In contrast, the respiration of the wild-type was not affected by EIPA addition, while that of mutant is decreased by about 30%. However, the respiration of mutant was not further inhibited by EIPA. Since this set of experiment is very crucial, we made statistic analysis of Table 1 experiment using ANOVA, as described in Table 1.

From the relatively low response of NuoM to photoaffinity analog of inhibitors fenpyroximate [17] and asimicin [19], it was suggested that NuoM may also be less sensitive to EIPA than that of NuoL. Therefore, under the current mutagenesis study of NuoL subunit, NuoM subunit is functional for its “indirect” proton pumping. However, we also plan to conduct this line of experiment using reconstituted proteoliposome system with purified E. coli complex I.

3. Discussion

3.1. A chimera model

There have been three types of approaches to the question of electron-proton coupling in complex I: (i) indirect coupling, (ii) chimera models of having both direct and indirect coupling, and (iii) direct coupling.

Yagi’s group [43], Brandt’s group [44] and Wikström’s group [45] proposed the indirect coupling. However, no experimental evidence for the molecular mechanism of the “indirect” coupling has so far been reported.

Sazanov et al. [12,13], Friedrich [46] pursued the chimera models (simultaneous direct and indirect proton pumping mechanisms).

Ohnishi and Salerno proposed a hypothesis that the proton pump is operated by the redox-driven local conformational change of a Q-binding protein, and the bound form of a SQ anion (QNf·−) serves as its gate [28]. However, we recognized that no need of explaining the proton pumping stoichiometry of (4H+/2e−) by only one “direct” coupling mechanism.

In the indirect mechanism, redox energy from the electron transfer chain is coupled with the proton pumping even through a long-range conformational change. From information obtained by disruption of purified bovine heart complex I into subcomplexes (1α, 1β, 1γ, 1λ) using detergent [12] and cryo-electron microscopy analysis [13,32], Sazanov et al. proposed that the intra-membrane subunits, ND4/NuoM and ND5/NuoL, are located at the distal end of the membrane arm, and may be involved in the long-distance conformation-driven proton pumping, since both ND4 and ND5 (as well as ND2) subunits have a high sequence similarity to multi- subunit K+/H+ or Na+/H+ antiporters [33,47,48].

In the recent paper, Sazanov’s group presented a strong structural clue for a long-range conformational change could be exerted by the movement of a piston-like structure made of a long amphipathic α-helix, which runs parallel to the membrane [30]. Since we now have an existing structural basis for a long-range conformational change, and a strong indication for indirect proton pumping from the mutagenesis data presented in this paper, we present a revised hypothesis that the SQ-gated direct proton pump transports 2H+, while the long-range conformational change-driven proton pump transports another 2H+ across the energy converting membranes [29].

3.2. Revised direct pump mechanism

The terminology of “direct” redox-coupled and “indirect” conformation- coupled systems has been often used. This terminology may be somewhat misleading because even the latter “indirect” proton pump system associated with respiration is still driven by the free energy coming from the redox reaction between NADH and Q pool, as we recently discussed in Ref. [29] which can account for (4H+/2e−) stoichiometry.

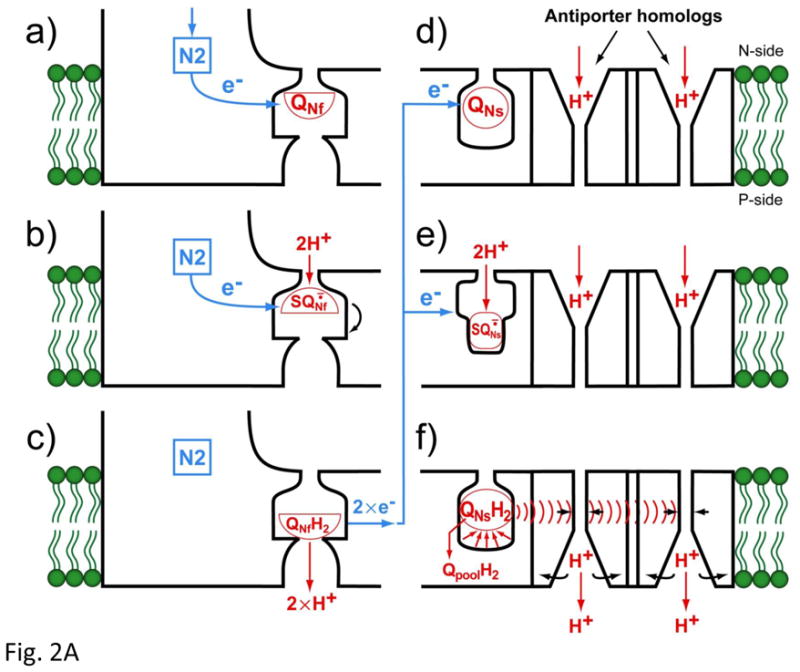

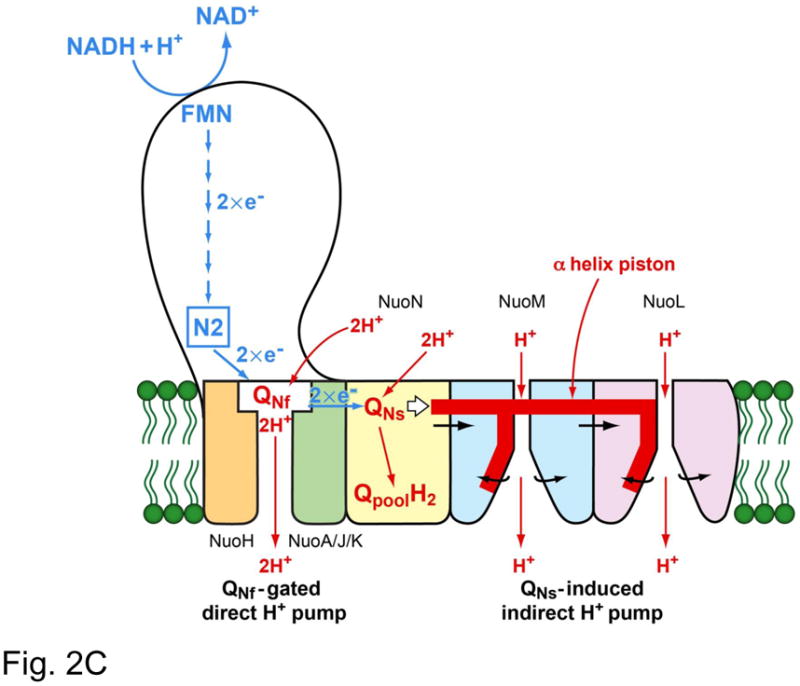

We now present a revised model involving two Q species. In Fig. 2A, the left panel (a–c) shows a direct pump mechanism which transports 2 protons (2H+/2e−). The reaction proceeds as follows: (a) QNf accepts an electron from iron-sulfur cluster N2 to form QNf·− which was found to be an anionic form below pH 8.5 [27]. (b) The intensity of QNf·− is very sensitive to the proton electrochemical potential . In mitochondria, this can be approximated with the membrane potential ΔΨ. The QNf·− has a higher affinity constant than both Q and QH2, and it binds tightly to the Q pocket. (c) When the SQ accepts a second electron from cluster N2, it takes up two protons from the matrix side (N-side). This triggers eversion of the SQ-binding protein. After the SQ is fully reduced to QH2 and eversion is complete, two electrons are transferred to QNs one by one, and two protons are released together into the proton- well, likely composed of a bundled NuoH, A, J, K subunits. This concludes a cycle in which (2H+/2e−) were vectorially transported by the “direct” pump.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2A. (a–c) Schematic mechanism of the SQNf gated direct proton pump and (d–f) SQNs-induced indirect proton pump.

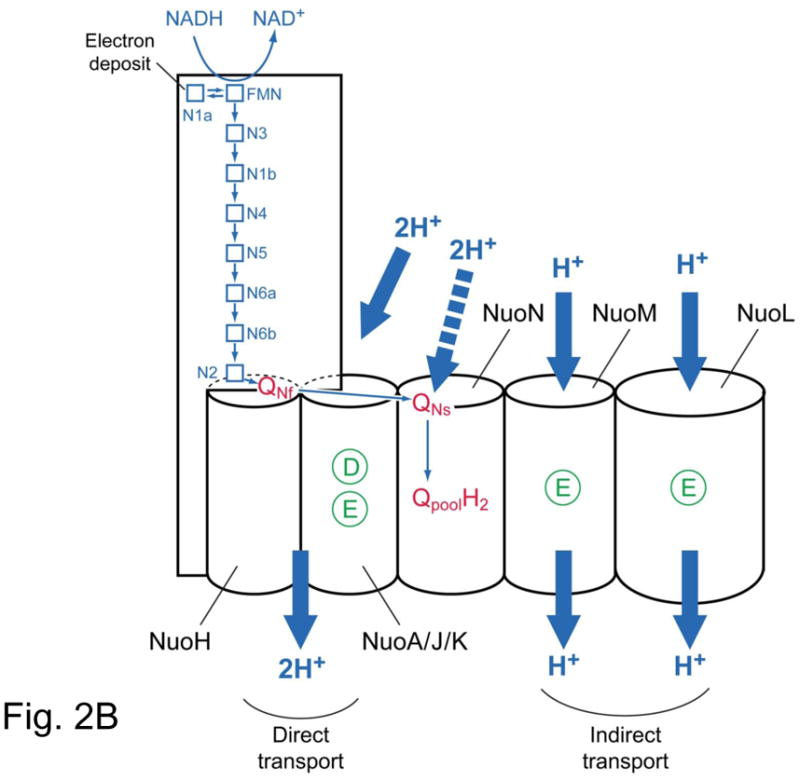

Fig. 2B. Schematic presentation of electron transfer and proton transport in complex I. Membrane subunit NuoH/ND1 NuoN/ND2 have no D (aspartic acid) and E (glutamic acid) residue which are involved in proton transport. The rest of subunit NuoA/ND3, Nuok/ND4L, NuoM/ND4, NuoL/ND5 have D and/or E, which are essential for the proton transport.

Fig. 2C. Our hypothetical model of proton transport in complex I. The direct transport is gated by QNf and carries 2 protons. The indirect transport is triggered by QNs and with the “piston” mechanism of Sazanov’s group [30], pumps 2 protons.

3.3. Indirect proton pump mechanism

(d) QNs is originally in the oxidized form. (e) When it accepts an electron, it is reduced to the SQ form, which must bind more strongly to the quinone-pocket since it is many orders of magnitude more stable than free ubiquinone. Kstab. of QNs·− = 2.0 in the isolated bovine heart complex I [14]. (f) Reduction with a second electron causes the uptake of 2 scalar protons from the N-side, producing the quinol (QNsH2), which has a much weaker binding constant than QNs·−. When the reduced Q is released from the quinonepocket to the Q pool, it causes a large conformational change of the pocket. This conformational change will be conducted through the long amphipathic α-helix (what Sazanov’s group called a “piston”) to reach the antiporter homologs. Then, the α-helix would cause the reorientation of the channel proteins [48], and release the proton at the P-side (intermembrane space).

3.4. How many antiporter channels could be driven by the “piston?”

According to the X-ray structure presented by Sazanov’s group, proton transport mechanisms of complex I are kind of indirect conformationally driven for all 3 antiporter homologs, NuoL, M, and N subunits. Three subunits individually transfer one proton each across the membrane through the “piston”-driven conformational mechanism [30]. In their model, complex I carries one proton through the Fe/S cluster N2/quinone-related indirect transport of one proton via bundled NuoH, A, J, and K subunits, and three protons through “piston”-driven conformational mechanism in NuoN, M, and L antiporter homolog subunits, individually. We would like to point out that the ratios of protons carried by the N2 pathway and the non-N2 pathway may be both (2H+/2e−) and (2H+/2e−), respectively, for the following reasons: (i) Although the cluster N2 transfers an electron, Q would receive it as two to complete the reaction cycle, unless we find a specific reason as in case of QA in the bacterial reaction center [49]. Therefore, it is hard to imagine to consider one proton is carried through one Q; (ii) although all of subunits NuoL, NuoM and NuoN have the high sequence similarity with antiporter homologs and they all contain highly conserved amino acidic residues in the intra-membrane domain, NuoN is different in that the mutations of acidic residues not change the proton transport of complex I [26]. (iii) Our result on the mutation study on NuoL are in favor of the idea that 2 protons are originally indirectly transported, but the mutation in NuoL kills one of them on average. We will elaborate this in the following section.

3.5. A model for proton transport in complex I

Fig. 2B shows how membrane subunits may be involved in the proton transport. NuoA/ND3, NuoK/ND4L maintain active D and E amino acid residues. Although NuoH/ND1 and NuoJ/ND6 do not contain D and E residues, still NuoA/J/K/H can be a candidate for the proton well through which 2 protons are translocated. The QNf binding site must be located in the loop region above NuoH. This region have D and E acidic residues and most of mitochondrial disease-related natural mutations are found in this region as we explained earlier.

The NuoL/ND5, NuoM/ND4 and NuoN/ND2 have high similarity of both primary sequence and X-ray structure with antiporter homologs [33], and that’s why Sazanov’s group assumed that a “piston” may open-close three subunits simultaneously. However, the D and E residues in NuoN/ND2 were not involved in proton transport [26]. On the other hand, NuoN/ND2 contains both Qbinding as well as inhibitor binding sites [19]. We suggest that this subunit is the site for QNs-binding. Perhaps the conformational change of QNs-binding subunit may push the “piston” and open the indirect proton translocation in NuoL and NuoM [31] by the Sazanov’s proposed mechanism (Fig. 2B).

Our model can explain why the photoaffinity labeling of fenpyroximate was completely prevented by the pre-incubation of not only quinone-pocket acting inhibitors such as rotenone and piericidin A [17], but also by EIPA [17]. The former inhibitors competed with fenpyroximate at the connecting portion between the “piston” like structure [30] and QNs, while EIPA inhibited the antiporter function of the NuoL/ND5 subunit.

In summary, we hypothesize that the proton transport in complex I has a “chimeric” structure; 2 protons are transported by the direct pump mechanism through QNf, and another 2 protons are by the indirect pump mechanism, which is triggered by the energy related to the site occupancy of QNs (Fig. 2C) [29].

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John C. Salerno at Kennesaw State University in GA and Dr. Takao Yagi at Scripps Research Institute in CA for their stimulating and helpful discussions. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant RO1GM030736 (to T.O).

Abbreviations

- BN-PAGE

blue native gel electrophoresis

- dNADH

deamino NADH

- EIPA

5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride

- Q

quinone

- SQ

semiquinone

- SQNf

fast-relaxing semiquinone species

- SQNs

slow relaxing semiquinone species

Footnotes

Nomenclature of subunits: bovine heart complex I subunits ND1, 2, 3,4,5,6 and 4L correspond to E. coli subunits NuoH, N, A, M, L, J and K.

Content of this paper was presented orally in the symposium at 2010 EBEC in Warsaw, Poland. A detailed full paper manuscript on the site-specific mutagenesis work by E. Nakamaru-Ogiso et al. is accepted for publication for J. Biol. Chem.

For statistical analyses, we used a statistic software (StatMate by ATMS Co.; Tokyo), we performed ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test. The linear regression analysis was also made using the same software.

References

- 1.Mitchell P. Proton translocation mechanisms and energy transduction by adenosine triphosphatases: an answer to criticisms. FEBS Lett. 1975;50:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell P. Keilin’s respiratory chain concept and its chemiosmotic consequences. Science. 1979;206:1148–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.388618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll J, Fearnley IM, Shannon RJ, Hirst J, Walker JE. Analysis of the subunit composition of complex I from bovine heart mitochondria. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:117–126. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300014-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yagi T, Yano T, Di Bernardo S, Matsuno-Yagi A. Procaryotic complex I (NDH-1), an overview. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1364:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofhaus G, Weiss H, Leonard K. Electron microscopic analysis of the peripheral and membrane parts of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) J Mol Biol. 1991;221:1027–1043. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guenebaut V, Schlitt A, Weiss H, Leonard K, Friedrich T. Consistent structure between bacterial and mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) J Mol Biol. 1998;276:105–112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnishi T. Iron-sulfur clusters/semiquinones in complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1364:186–206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnishi T, Nakamaru-Ogiso E. Were there any “misassignments” among iron-sulfur clusters N4, N5 and N6b in NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (complex I)? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wikstöm M. Two protons are pumped from the mitochondrial matrix per electron transfered between NADH and ubiquinone. FEBS Lett. 1984;169:300–304. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galkin AS, Grivennikova VG, Vinogradov AD. H+/2e-stoichiometry in NADH-quinone reductase reactions catalyzed by bovine heart submitochondrial particles. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sazanov LA, Hinchliffe P. Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilus. Science. 2006;311:1430–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1123809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sazanov LA, Peak-Chew SY, Fearnley IM, Walker JE. Resolution of the membrane domain of bovine complex I into subcomplexes: implications for the structural organization of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7229–7235. doi: 10.1021/bi000335t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranova EA, Morgan DJ, Sazanov LA. Single particle analysis confirms distal location of subunits NuoL and NuoM in Escherichia coli complex I. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;159:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohnishi T, Johnson JE, Jr, Yano T, Lobrutto R, Widger WR. Thermodynamic and EPR studies of slowly relaxing ubisemiquinone species in the isolated bovine heart complex I. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohnishi T, Ohnishi ST, Shinzawa-Ito K, Yoshikawa S. Functional role of coenzyme Q in the energy coupling of NADH-CoQ oxidoreductase (complex I): stabilization of the semiquinone state with the application of inside-positive membrane potential to proteoliposomes. BioFactors. 2008;32:13–22. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnitsky S, et al. EPR characterization of ubisemiquinones and iron-sulfur cluster N2, central components of the energy coupling in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in situ. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2002;34:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1016083419979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Sakamoto K, Matsuno-Yagi A, Miyoshi H, Yagi T. The ND5 subunit was labeled by a photoaffinity analogue of fenpyroximate in bovine mitochondrial complex I. Biochemistry. 2003;42:746–754. doi: 10.1021/bi0269660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Seo BB, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. Amiloride inhibition of the proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of mammals and bacteria. FEBS Lett. 2003;549:43–46. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Han H, Matsuno-Yagi A, Keinan E, Sinha SC, Yagi T, Ohnishi T. The ND2 subunit is labeled by a photoaffinity analogue of asimicin, a potent complex I inhibitor. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:883–888. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth R, Hagerhall C. Transmembrane orientation and topology of the NADH:quinone oxidoreductase putative quinone binding subunit NuoH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504:352–362. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murai M, Sekiguchi K, Nishioka T, Miyoshi H. Characterization of the inhibitor binding site in mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase by photoaffinity labeling using a quinazoline-type inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2009;48:688–698. doi: 10.1021/bi8019977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace DC. Diseases of the mitochondrial DNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:1175–1212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.005523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tocilescu MA, Fendel U, Zwicker K, Kerscher S, Brandt U. Exploring the ubiquinone binding cavity of respiratory complex I. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29514–29520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fendel U, Tocilescu MA, Kerscher S, Brandt U. Exploring the inhibitor binding pocket of respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurki S, Zickermann V, Kervinen M, Hassinen I, Finel M. Three conserved Glu. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13496–13502. doi: 10.1021/bi001134s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amarneh B, Vik SB. Mutagenesis of subunit N of the Escherichia coli complex I. Identification of the initiation codon and the sensitivity of mutants to decylubiquinone. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4800–4808. doi: 10.1021/bi0340346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yano T, Dunham WR, Ohnishi T. Characterization of the delta muH+-sensitive ubisemiquinone species (SQ(Nf)) and the interaction with cluster N2: new insight into the energy-coupled electron transfer in complex I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1744–1754. doi: 10.1021/bi048132i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohnishi T, Salerno JC. Conformation-driven and semiquinonegated proton-pump mechanism in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4555–4561. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohnishi ST, Salerno JC, Ohnishi T. Possible roles of two quinone molecules in direct and indirect proton pumps of bovine heart NADH-quinone osicoreductase (complex I) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010. 06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efremov RG, Baradaran R, Sazanov LA. The architecture of respiratory complex I. Nature. 2010;465:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature09066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohnishi T. Piston drives a proton pump. Nature. 2010;465:428–429. doi: 10.1038/465428a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baranova EA, Holt PJ, Sazanov LA. Projection structure of the membrane domain of Escherichia coli respiratory complex I at 8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:140–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathiesen C, Hägeräll C. Transmembrane topology of ther NuoL, M and N subuits of NADH:quinone oxidoreductase and their homologues among membrane-bound hydrogenase and bona fide antiporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1556:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao MC, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Characterization of the membrane domain subunit NuoK (ND4L) of the NADH-quinone oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9545–9554. doi: 10.1021/bi050708w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kao MC, Bernardo S, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Matsuno-Yagi A, Miyoshi H, Yagi T. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3562–3571. doi: 10.1021/bi0476477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres-Bacete J, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36914–36922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsushita K, Ohnishi T, Kaback HR. NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase of E. coli aerobic respiratory chain. Biochemistry. 1987;26:7732–7737. doi: 10.1021/bi00398a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kao MC, Di Bernardo S, Perego M, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Functional roles of four conserved charged residues in the membrane domain subunit NuoA of the proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32360–32366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal Biochem. 1991;199:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittig I, Braun HP, Schägger H. Blue native PAGE. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dlaskova A, Hlavata L, Jezek J, Jezek P. Int. J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2098–2109. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. The proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase in the respiratory chain: the secret unlocked. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2266–2274. doi: 10.1021/bi027158b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandt U. Energy converting NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:69–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Euro L, Belevich G, Verkhovsky MI, Wikstrom M, Verkhovskaya M. Conserved lysine residues of the membrane subunit NuoM are involved in energy conversion by the proton-pumping NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1166–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedrich T. Complex I: a chimera of a redox and conformation driven proton pumps? J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2001;33:169–177. doi: 10.1023/a:1010722717257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedrich T, Weiss H. Theor. Biol. 1997;187:529–540. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunte C, Screpanti E, Venturi M, Rimon A, Padan E, Michel H. Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature. 2005;435:1197–1202. doi: 10.1038/nature03692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamura MY, Paddock ML, Graige MS, Feher G. Proton and electron transfer in bacterial reaction centers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:148–163. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]