FK 506, a potent immunosuppressive macrolide antibiotic, has undergone clinical testing at the Presbyterian University and Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh since January 1989. The initial clinical trials were directed at liver transplant recipients with refractory rejection1,2 and pursuant to these dramatic and gratifying results FK 506 was introduced as primary immunosuppression in kidney and liver recipients in March 1989.3,4 Since October 1989, in a prospective clinical trial, 30 patients have undergone orthotopic cardiac transplantation with FK 506 and low-dose steroids as primary immunosuppression. Dramatic results were also attained in five patients with cardiac rejection refractory to all known conventional treatment who underwent rescue therapy with FK 506.

METHODS

Patient Group

Thirty patients were prospectively entered into this study from October 1989 to August 1990. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to transplantation for the use of FK 506 and steroids as the sole immunosuppressive therapy: five patients received conventional cyclosporine-based immunosuppression during this period.

In this study group there were 25 males and five females, 22 were adults and eight children (age range 22 days to 61 years) and eight (27%) required mechanical circulatory support prior to transplantation in the form of the Novacor left ventricular assist device (LVAS) (3), intraaortic balloon pump (IABP) (4), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (1). The etiology of cardiomyopathy included idiopathic (11), ischemic (11), congenital (5), valvular (2), and hypertrophic (1). In the eight pediatric patients (<18 years), five had complex congenital heart disease. Three of the children each had five previous thoracic operations, one was on ECMO for 8 days prior to transplantation, and one child underwent cardiac transplantation at 22 days of age for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Median follow-up of these 30 patients was 110 days (range 13–317 days) as of August 1990. No attempt was made to selectively enroll patients in this study based on severity of illness or preoperative status.

Five patients were treated with FK 506 rescue therapy who had cardiac rejection refractory to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. There were three children and two adults in this group. Two of these patients were referred to our institution from other centers.

FK 506 Therapy

FK 506 was administered intravenously for 24–72 hours after cardiac transplantation at a dose of 0.15/mg/kg/d in two divided doses. Oral FK 506 was begun 36–72 hours after transplantation, with a 12-hour overlap with the intravenous drug, upon return of gastrointestinal function. The oral maintenance dose of FK 506 required to attain a level of 1.5–3 ng/mL (12 hour through serum ELISA by the technique of Temura)5 has ranged from 0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg/d, Methylprednisolone, 7 mg/kg, was administered intravenously in the operating room and 5 mg/kg postoperatively for 24 hours in three divided doses. Thereafter patients received 0.15 mg/kg/d prednisone orally once a day. Prednisone was then tapered and discontinued based on rejection history.

Other Agents

All patients entered into the FK 506 immunotherapy protocol were placed on prophylactic oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, acyclovir, and mycostatin.

Monitoring for Rejection

Posttransplant surveillance on all patients involved weekly transvenous endomyocardial biopsies (excluding the neonatal patient) during hospitalization and at slowly increased intervals after discharge. Biopsies were graded using hematoxylin and eosin staining after light microscopy by a pathologist who was blinded to the immunosuppressive protocol of the patient. Biopsy grades were defined according to a modified Billingham scale. Rejection was defined by the presence of myocyte necrosis in association with an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (grade 3 or moderate rejection) or with hemorrhage (grade 4 or severe rejection).

Monitoring for Infection

All patients were followed by an infectious disease specialist. Pretransplant titers for hepatitis B, herpesvirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), toxoplasma, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were performed on all donors and recipients. The diagnosis of infection was made using clinical criteria as previously defined by this institution.6

Complete blood screening was performed daily in the hospital and at all follow-up visits. Questionnaires to identify untoward side effects of FK 506 were completed on all patients.

RESULTS

Survival

Twenty-six of 30 (86.6%) patients entered into this trial are alive. The earliest death occurred on the fourth postoperative day secondary to pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure. Two other deaths occurred at 30 and 54 days from causes unknown; neither of these latter two patients had any episode of rejection. One patient died of sudden death at home on an exercise cycle and permission was denied for postmortem examination. The other patient died of low cardiac output, the etiology of which remains unclear despite complete postmortem examination; no evidence of cellular or humoral rejection was evident in the heart. The fourth and latest death occurred in a child at 90 days secondary to sepsis. This child had preexisting lung disease and bronchiectasis and succumbed to pulmonary and disseminated cryptococcal infection. Toxoplasmosis and cytomegalovirus infections also contributed to this patient’s demise. In addition, this child had severe cachexia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypogammaglobulinemia secondary to his cardiac condition. His immunosuppression consisted of very low-dose FK 506 without steroids and no cardiac rejection occurred. No mortality has been attributed to FK 506 therapy or to acute or refractory cardiac rejection.

Rejection

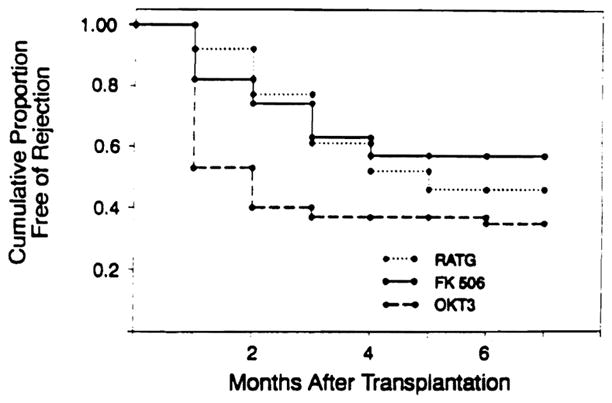

At 3 months posttransplant there were 10 episodes of rejection in eight patients. Beyond 3 months no new episodes of rejection had occurred. Four episodes of rejection occurred at 4, 5 and 6 months posttransplant in three patients with prior episodes of rejection during the first 3 months. The episodes of treated (moderate or severe, modified Billingham criteria 3 or 4) rejection at 90 days in this study were 0.45 per patient (N = 22). The actuarial freedom from rejection at 3 months was 60% and remained so at 6 and 9 months (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Actuarial freedom from rejection.

Rejection episodes of moderate severity (Billingham criteria 3) were preferentially treated by increased doses of FK 506, 4–8 mg/d in the adult patients and 1–4 mg/d in the pediatric patients. Moderate or severe rejection (Billingham criteria 3 or 4) was treated either by intravenous methylprednisolone, 1 g for 24 or 48 hours, or with a short course oral prednisone taper, 100–20 mg over 5 days, in those patients in whom FK levels were already in the high therapeutic range or in whom azotemia (BUN >50 and creatinine >2.0) limited further manipulation of FK therapy. Only one patient required the addition of other immunosuppressive agents; 4 months posttransplant he received 5 days of OKT3 (total dose 25 mg) and azathioprine was added to this therapy.

Infection

Three major infections in two patients were present prior to cardiac transplantation. One patient had two pretransplant infections, staphylococcal line sepsis secondary to an IABP, and a positive sternal wound culture for Candida at the time of Novacor LVAS removal. This same patient had pulmonary emboli and infarctions yet remained free of infection posttransplant managed on FK 506 as his sole immunosuppressive agent. Amphotericin was administered for 5 weeks after transplantation. The other patient with a pretransplant infection had a klebsiella pneumonia during IABP support which had been treated for 8 days when a donor heart became available. This patient recovered without further infection.

Posttransplant there were eight infections in seven of 30 patients on primary FK 506 therapy. No patient in the rescue group had a diagnosed infection. There were four (13%) major infections which consisted of two gastrointestinal CMV infections which both responded to ganciclovir, one gram-negative pneumonia, and one cryptococcemia with CMV and toxoplasmosis which was fatal (see “Survival”). There were four (13%) minor infections, two herpes infections, and two varicella infections in children. Freedom from major infection in the primary FK 506 group at the median follow-up of 110 days is 87%.

Cardiac Function

All surviving patients enjoy excellent cardiac function. The average left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in the group measured by gated nuclear scan and/or echocardiography is 70%. The range of LVEF is 58% to 75% at the time of longest follow-up.

Renal Function and Hypertension

In 20 patients followed for more than 90 days the average serum creatinine prior to transplant was 0.9 ng/dL. When FK 506 was administered intravenously at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg/d, infused either as bolus therapy twice a day or as a continuous 24-hour infusion, there was associated nephrotoxicity. Three patients (10%) required dialysis in the perioperative period; however, renal function returned near baseline within 7–10 days. One of these patients was the 22-day-old neonate who had associated renal vein thrombosis secondary to venous catheters. One of the two adults who required dialysis suffered a cardiac arrest on induction to anesthesia and had an IABP inserted; these events were associated with mild hepatic dysfunction and FK 506 levels greater than 20 ng/mL in the early posttransplant period. Excluding these three patients who required dialysis, peak renal dysfunction occurred at the first postoperative week and the average serum creatinine was 2.6 ng/dL (SD = 1.03). This peak renal dysfunction was associated with an average FK 506 level of 5.1 ng/mL (range 0.8–12 ng/mL). The average serum creatinine at 3 months follow-up was 1.96 ng/dL (SD = .86) and was attained by most patients by the second postoperative week.

Hypertension is rare in patients following cardiac transplantation treated with FK 506 and low-dose steroids. Only three of 20 patients (15%) followed for more than 3 months have required antihypertensive treatment and all are well controlled on a single agent.

Cardiac Rescue Therapy

Five patients were treated with FK 506 who suffered from cardiac rejection refractory to aggressive conventional immunotherapy. All of these patients had been treated with cyclosporine, azathioprine, and steroids; all had received two or more courses of intravenous steroids and two or more courses of antilymphocyte therapy (RATG, Minnesota ALG, or OKT3) and had persistent rejection. In this rescue group three were children, two from our own institution and one referred from another center. The three children suffered from chronic steroid treatment and had marked cushingoid habitus. One adult from our program had chronic rejection over 3 years; the other adult had unrelenting moderate to severe rejection during the first three posttransplant months and was referred to Pittsburgh for rescue therapy.

The rescue patients have tolerated the switch from cyclosporine to FK 506 without significant complications. Cyclosporine was discontinued 24–48 hours prior to FK 506 induction. No loading dose of FK 506 was administered. The patients were begun on oral FK 506, 0.3 mg/kg/d, in two divided doses. Azathioprine was discontinued and steroids were given at half the maintenance dose. Pending improvement in subsequent biopsies, steroids were tapered and all five patients are on one-quarter their previous prednisone dose. All of the children have significantly resolved their cushingoid features; one young girl lost 12.2 kg. The two patients referred from other centers now have normal endomyocardial biopsies. Our three patients experienced significant clinical improvement and their endomyocardial biopsy readings were the mild range (modified Billingham criteria 1–2).

The two adult FK 506 rescue patients both complained of muscle and joint aches and lower limb paresthesias for the first few weeks following the switch in therapy. These have all resolved. Presumably, these symptoms were related to cyclosporine/FK 506 interactions as they have not been observed in primary FK 506 patients. Renal function has remained normal in all rescue patients. The range of follow-up in this group is 90–275 days.

Metabolic Studies and Side Effects

There were eight insulin-dependent diabetics in the 30 patients on primary FK 506 therapy following cardiac transplantation. Three of these eight diabetics were insulin-dependent prior to transplantation. There were five new-onset diabetic patients of 27 nondiabetic recipients (18.5%). All of the new-onset diabetics were also on prednisone (average dose 7 mg/d).

Continued monitoring of hematologic and coagulation indices as well as hepatic function failed to reveal any abnormalities in our patients at this follow-up interval. Cholesterol and triglycerides have been slightly lower than those in cyclosporine-treated patients; however, this is not statistically significant. Two patients have borderline elevated uric acid levels. Slightly elevated serum potassium levels have also been observed in some patients, independent of renal dysfunction, and we have avoided the exogenous administration of potassium in this group unless specifically indicated (serum K+ < 3.5 mEq/L).

Side effects have been rare despite routine questionnaires during hospitalization and during outpatient follow-up. There have been no seizures, cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), or neuropathies secondary to FK 506. One patient in the primary therapy group had a thromboembolic occipital CVA with associated hemorrhage and seizure from which he has recovered with little residual deficit. There have been occasional reports of extremity paresthesia and temperature malsensations usually associated with elevated FK 506 levels. Muscle aches and mild insomnia were also reported rarely. Notably absent in this patient group were complaints of gingival hyperplasia, tremor, or hirsutism.

DISCUSSION

These preliminary results with FK 506 and low-dose steroid immunosuppression hold tremendous promise for the future, as both primary immunotherapy in cardiac transplantation and as an effective agent for rescue therapy in refractory cardiac rejection. In a prospective randomized study performed at the University of Pittsburgh comparing RATG to OKT3 immunoprophylaxis with cyclosporine-based triple-drug therapy the best immunosuppressive results were obtained with RATG prophylaxis. Using RATG immunoprophylaxis and cyclosporine, azathioprine, and high-dose (20 mg/d) prednisone the actuarial freedom from rejection at 90 days posttransplant was 62% with 0.42 episode of rejection per patient.7 The actuarial freedom from rejection in the FK 506 and low-dose steroid immunotherapy group at 90 days posttransplant is 60% with 0.45 episode of rejection per patient. We have been impressed with the ability of this new agent to attain comparable immunosuppression in cardiac transplant recipients to the very best immunosuppressive protocol at the University of Pittsburgh during the last decade. This level of immunosuppression has been achieved without antilymphocyte therapy, without immunoprophylaxis, without azathioprine, and with marked reduction in the steroid requirement. Ten of the 30 patients in this study are on no steroids at all, including all eight pediatric patients. The average steroid dose in the adults is 8.6 mg of prednisone per patient. The ability of FK 506 to reverse cardiac rejection which has been refractory to aggressive treatment with conventional immunotherapeutic tools and the relatively low rate of major (13%) and minor (13%) infections is further testament to the potency and selectivity of its immunosuppressive actions. Another added advantage of FK 506 is the flexibility it introduces to immunosuppressive management. Five of 10 episodes of rejection which occurred in the first 3 months posttransplant were treated by merely increasing the FK 506 dose. All five patients treated for rejection by increasing FK 506 dose had histological improvement on endomyocardial biopsy the following week and only two of the patients have had subsequent rejection. The concept of augmenting immunosuppression and treating rejection by increasing baseline immunotherapy adds a new tool to our armamentarium of antirejection therapy. The biological and immunological basis for this quality of FK 506 is presently under intense study at the University of Pittsburgh.

Despite the excellent tolerance of FK 506 by patients and few observed or reported side effects, renal dysfunction is a price paid when the drug is used as described in this report. We believe that systematic overdosing has occurred in patients receiving FK 506 intravenously in the perioperative period in our attempt to achieve high early FK 506 levels. We have changed initial bolus intravenous FK 506 therapy to continuous infusion, and now, more recently, have lowered the initial intravenous dose to a single 24-hour constant-infusion dose at 0.075 mg/kg, with enteral FK 506 begun on the first postoperative day. The three patients treated in this manner have not suffered from azotemia and oliguria. Further refinements in our knowledge regarding FK 506 dosing and therapeutic levels together with the diminished incidence of hypertension may actually improve the long-term outlook for renal function in cardiac transplant recipients. When compared to the 40 cardiac transplant recipients transplanted at the University of Pittsburgh prior to October 1989, the incidence of hypertension was 70% as opposed to 15% in the FK 506 group (P < .001).

Cardiac function and the quality of life in our small patient group have been excellent. Concerns regarding vasculitis and neuropathy have not been realized. The benefit of steroid sparing and the lack of nonspecific bone marrow suppression, antilymphocyte, and antihypertensive therapy hold tremendous promise for the future of cardiac transplant recipients.

References

- 1.Starzl TE, Todo S, Fung J, Demetris AJ, Venkataramanan R, Jain A. Lancet. 1989;2:1000. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fung JJ, Todo S, Jain A, et al. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todo S, Fung JJ, Demetris AJ, Jain A, Venkataramanan R, Starzl TE. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starzl TE, Fung JJ, Jordan M, et al. JAMA. 1990;264:63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamaura K, Kobayashi M, Hashimoto K, Kojima K, Nagase K, Iwasaki K, Kaizu T, Tanaka H, Niwa M. Transplant Proc. 1987;19(Suppl 16):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusne S, Dummer JS, Singh N, et al. Medicine. 1988;67:132. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198803000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kormos RL, Armitage JM, Dummer JS, Miyamoto, Griffith BP, Hardesty RL. Transplantation. 1990;49:306. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]