Abstract

Nedd4-2 is an archetypal HECT ubiquitin E3 ligase that disposes target proteins for degradation. Because of the proven roles of Nedd4-2 in degradation of membrane proteins, such as epithelial Na+ channel, we examined the effect of Nedd4-2 on the apical Ca2+ channel TRPV6, which is involved in transcellular Ca2+ transport in the intestine using the Xenopus laevis oocyte system. We demonstrated that a significant amount of Nedd4-2 protein was distributed to the absorptive epithelial cells in ileum, cecum, and colon along with TRPV6. When co-expressed in oocytes, Nedd4-2 and, to a lesser extent, Nedd4 down-regulated the protein abundance and Ca2+ influx of TRPV6 and TRPV5, respectively. TRPV6 ubiquitination was increased, and its stability was decreased by Nedd4-2. The Nedd4-2 inhibitory effects on TRPV6 were partially blocked by proteasome inhibitor MG132 but not by the lysosome inhibitor chloroquine. The rate of TRPV6 internalization was not significantly altered by Nedd4-2. The HECT domain was essential to the inhibitory effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 and to their association. The WW1 and WW2 domains interacted with TRPV6 terminal regions, and a disruption of the interactions by D204H and D376H mutations in the WW1 and WW2 domains increased TRPV6 ubiquitination and degradation. Thus, WW1 and WW2 may serve as a molecular switch to limit the ubiquitination of TRPV6 by the HECT domain. In conclusion, Nedd4-2 may regulate TRPV6 protein abundance in intestinal epithelia by controlling TRPV6 ubiquitination.

Keywords: Calcium Channels, Calcium Transport, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Intestine, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitination, Nedd4, Nedd4-2, TRPV5, TRPV6

Introduction

TRPV6 (transient receptor potential cation channels, vanilloid subfamily, subtype 6; also known as CaT1) is an epithelial Ca2+ channel expressed in the apical membrane of intestine epithelial cells (1, 2). It mediates the first step of transcellular Ca2+ transport and is considered to be a gatekeeper for active Ca2+ absorption. The biosynthesis of TRPV6 is highly regulated by 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 at the transcriptional level (3). This is supported by the fact that multiple vitamin D-responsive elements have been identified in the TRPV6 gene promoter (4). Furthermore, a 90% reduction of duodenal TRPV6 mRNA was observed in vitamin D receptor knock-out (KO) mice (5). 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 levels were elevated in Trpv6 KO mice together with a 60% reduction in intestinal Ca2+ absorption, indicating a key role of vitamin D in regulating the synthesis of TRPV6 (6). TRPV6 is also induced by estrogens and the reproductive cycle at transcriptional levels (7). The trafficking and stability of TRPV6 are regulated by proteins such as S100A10-annexin II complex (8) and β-glucuronidase Klotho, respectively (9, 10). The serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinases SGK1 and SGK3 have been reported to regulate TRPV6 (11). Our previous work showed that WNK3, a member of the WNK (with no lysine (K)) protein kinase family, increases complexly glycosylated mature TRPV6 protein at the cell surface (12), whereas WNK4 has little effect (13). In contrast to biosynthesis, trafficking, and stability of TRPV6, little is known about the pathway via which TRPV6 protein is degraded. Identification of mechanisms responsible for TRPV6 degradation will provide new insights into the regulation of intestinal Ca2+ absorption.

Nedd4-2 (neuronal precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4-2) is an archetypal member of the E3 ligase family. It is well known for regulating cell surface stability of membrane proteins by the addition of ubiquitin chains to them, followed by endocytosis and lysosomal or proteasomal degradation (14–16). The best characterized Nedd4-2 substrate is the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC)4 (17, 18). Nedd4-2 inhibits ENaC by binding to its PY motif (19). This down-regulation of ENaC is physiologically important because ENaC mutants lacking the PY motif disrupt Nedd4-2 binding and cause Liddle syndrome, a hereditary hypertension caused by elevated ENaC stability/activity (17, 19, 20).

Nedd4-2 is broadly expressed in many tissues, such as brain (21), lung (22), liver (21), prostate (23), kidney (22), and intestine (22, 24). In line with its distribution, it has a variety of membrane proteins as substrates. The ubiquitination mediated by Nedd4-2 is required for the down-regulation of many membrane proteins, such as voltage-gated Na+ channel (25), neurotrophin receptor TrkA (26), potassium channel KCNQ (27, 28), Cl− channel ClC-2 (29), Na+-glucose co-transporter SGLT1 (30), and Na+-phosphate co-transporter NaPi IIb (24). The list of ion channels/transporters regulated by Nedd4-2 has grown longer since the identification of ENaC as a substrate of Nedd4-2. Nevertheless, physiologically relevant substrates of Nedd4-2 are yet to be identified.

Based on the role of Nedd4-2 in degradation of membrane proteins, we tested the effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 in this study. We show that TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 are co-expressed in the intestinal tract and that TRPV6 is degraded by Nedd4-2 via the ubiquitination pathway. We also found that an interaction between TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 WW1 and WW2 domains plays a critical role in controlling the degradation of TRPV6.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

cDNA Constructs

The human TRPV6 cDNA was described previously (31). The human Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 cDNAs (hNedd4, BC152562; hNedd4-2, BC032597 and BC019345) were purchased from Open Biosystems, Inc. (Huntsville, AL). The cDNAs were subcloned into the Xenopus laevis oocyte expression vector pIN (13, 32). To obtain the full-length hNedd4-2, the XhoI/EcoRV fragment of BC019345 was used to replace the corresponding segment in BC032597, which lacks 1067–1198 bp in the Nedd4-2 open reading frame. The resultant cDNA was cloned into our pIN vector as the full-length human Nedd4-2. To detect protein expression of the Nedd4-2 construct lacking the homology to the E6-associated protein C terminus (HECT) domain and for the purpose of co-immunoprecipitation, a hemagglutinin epitope (HA tag) was added to the N terminus of Nedd4-2 using a PCR-based approach. The Nedd4-2 C922S mutant was generated using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions and confirmed by sequencing.

Ca2+ Uptake in X. laevis Oocytes

The animal protocol used in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In vitro transcription, injection of the resultant capped synthetic cRNAs into oocytes, and a 45Ca2+ uptake assay in oocytes were conducted as described previously (12). cRNAs were injected at 12.5 ng/oocyte unless stated otherwise. When a combination of two or three cRNAs was required, we mixed the cRNAs in such a way that the concentration of individual cRNAs was maintained. Defolliculated X. laevis oocytes were kept at 18 °C in 0.5× L-15 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 5% heat-inactivated horse serum, penicillin at 10,000 units/liter, streptomycin at 10 mg/liter, and amphotericin B at 25 μg/liter. Two days after injection, uptake experiments were carried out at room temperature (24 °C) for a period of 30 min. Standard uptake solution contained 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2 (including 45CaCl2 at 10 μCi/ml), and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. Oocytes were washed six times with ice-cold standard uptake solution without 45CaCl2 after a 30-min uptake. They were then dissolved in 10% SDS solution. The incorporated 45Ca2+ was determined using a scintillation counter. Ca2+ uptake data are presented as mean values from at least three experiments with 7–9 oocytes/group, using the S.E. as the index of dispersion.

Two-microelectrode Voltage Clamp

Voltage clamp experiments were performed as described previously (33). The resistance of microelectrodes filled with 3 m KCl was 0.5–5 megaohms. In experiments involving voltage jumping or holding, currents and voltages were digitized at 0.3 and 200 ms/sample, respectively. After ∼3 min of stabilization of membrane potential following impalement with the microelectrodes, the oocyte was clamped at a holding potential of −50 mV. Then 100-ms voltage pulses between −160 and +60 mV, in 20-mV increments, were applied, and steady state currents were obtained as the average values 80–95 ms after initiation of the voltage pulses. The standard perfusion solution contained 100 mm choline chloride, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.5 with Tris base and HCl. Choline chloride was substituted with NaCl when Na+-evoked currents were tested.

Western Blot Analysis

Two days after injection with different cRNAs, oocytes were washed with modified Barth's solution (MBS). Oocytes were lysed with lysis buffer (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris·Cl, 1% Triton X-100 plus protease inhibitor mixture, pH 7.6) at 20 μl/oocyte and centrifuged at 2,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove the cellular debris and yolk proteins. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (7.5% acrylamide). In general, extract supernatant corresponding to one oocyte was loaded per lane. After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by multiple washes in PBS-Tween 20. Monoclonal anti-HA antibody (product H9658, 1:5,000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The rabbit anti-TRPV6 antiserum (1:3000) was customer-raised with a synthetic peptide antigen corresponding to amino acids 359–377 of the first extracellular loop of TRPV6 by Open Biosystems, Inc. This antiserum specifically recognizes TRPV6 without cross-reaction with TRPV5. The anti-Nedd4-2 antibody (ab46521, 1:2,000) was purchased from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). The anti-β-actin antibody (sc-47778, 1:5,000) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were incubated in the blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature, followed by multiple washes with PBS-Tween 20. Chemiluminescence was detected using a SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate kit (Pierce) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

Surface Expression and Internalization Measurement

Surface expression of TRPV6 was detected by an anti-TRPV6 antiserum, which recognizes the extracellular loop of TRPV6 using an approach described previously (12). Water-injected oocytes and oocytes injected with cRNA for TRPV6 alone or with Nedd4-2 were incubated at 18 °C for 2 days. The oocytes were then blocked in MBS with 1% BSA at 4 °C for 60 min, labeled with our anti-TRPV6 antiserum (1:10,000) in 1% BSA at 4 °C for 30 min, and washed at 4 °C (two times for 15 min each in MBS with 1% BSA; four times for 5 min each in MBS). For measuring the endocytosis rate of TRPV6, each group of oocytes was then incubated in MBS at room temperature to allow internalization of antibody-labeled surface TRPV6 proteins. At each time point (0, 15, and 30 min), oocytes were transferred to ice-cold MBS. After that, all of the oocytes were fixed in PLP fixative solution (2% paraformaldehyde, 0.075 m lysine, 0.037 m sodium phosphate buffer, and 0.01 m NaIO4, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 1 h. The fixed oocytes were washed with ice-cold MBS for 5 min and then with ice-cold MBS with 1% BSA for 15 min three times. The oocytes were incubated with HRP-coupled secondary antibody (sc-2004, goat anti-rabbit, 1:20,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 1% BSA for 30 min, followed by extensive wash with MBS at 4 °C (seven times for 5 min each). Individual oocytes were placed in 25 μl of SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and incubated at room temperature for exactly 1 min. Chemiluminescence was quantified using an FB12 single tube luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany) and recorded by FB12/Sirius software. Background chemiluminescence signals from control oocytes were subtracted, and the levels of signal at time 0 were defined as 100%. Chemiluminescence signals were plotted as a function of time, and the curves were fitted using linear regression with SigmaPlot 10 (Systat Software, Chicago, IL). The slopes of the curves represent rate of TRPV6 internalization.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HA-Nedd4-2 and TRPV6 were co-expressed in X. laevis oocytes. Two days after injection, oocytes were treated with 25 μm MG132 in 0.5× L-15 medium for 5 h. Oocytes were then washed with modified Barth's solution and lysed with lysis buffer at 20 μl/oocyte and centrifuged at 2,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove the cellular debris and yolk proteins. Samples were precleared by adding Protein A/G-agarose (sc-2003, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) to remove nonspecific agarose binders from the protein mixture. Our customer-made TRPV6 antiserum (1:20) was then added to the lysates and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. Next, Protein A/G-agarose was added, and samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated proteins bound to the agarose beads were washed three times using PBS, and proteins were eluted from the beads by boiling the samples in loading buffer. The eluted samples were analyzed for the presence of HA-Nedd4-2 by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody.

Purification of GST Fusion Protein

Nedd4-2 C2, WW1, WW2, WW3, WW4, and HECT domains were amplified by PCR and then subcloned into pGEX-6P-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences) and transferred into competent Escherichia coli BL21 by the heat shock method. After incubation at 37 °C overnight, a one-fiftieth volume culture was transferred to 25 ml of fresh LB medium with 10 mg/ml ampicillin. Fusion protein expression was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.1 mm after A600 of liquid cultures to 0.6–0.8 and continued incubation for an additional 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifuging at 2,500 × g for 10 min and lysed by adding lysozyme at 0.1 mg/ml and DNase I at 5 units/ml. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, supernatant was transferred to a glutathione-Sepharose 4B MicroSpin column (Amersham Biosciences) and mixed gently at room temperature for 5–10 min or at 4 °C overnight to ensure optimal binding of GST proteins to the glutathione-Sepharose 4B matrix. After washing by PBS, purified GST fusion protein was eluted by glutathione elution buffer.

Far Western Analysis

Far Western analysis was performed as described (34). 35S-Labeled protein probes were synthesized using TNT® SP6 High-Yield Master Mix following the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). The translation products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and radioautography.

To prepare membranes with Nedd4-2 domains or the TRPV6 C-terminal region, each GST fusion protein was separated by SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide) and was transferred to PVDF membranes by standard procedures. The membranes were blocked at room temperature for 2 h in Blotto solution (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 25 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5% nonfat dry milk). Then the membranes were incubated in Hyb 75 (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 75 mm KCl, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 1% nonfat dry milk) for 15 min at room temperature. 35S-Labeled probes were diluted in 3 ml of Hyb 75. Far Western experiments were carried out at 4 °C with gentle rocking for 4–5 h or overnight. The membranes were washed for 15 min three times with Hyb 75 and then air dried and exposed to x-ray films.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

Intestinal tissues were harvested from healthy adult rats immediately after anesthesia. Approximately 1.5–2-cm tissues were excised from duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon. Tissues were washed by ice-cold PBS to remove food residues. Using TRIzol reagent, total RNA was isolated according to the instructions of the manufacture (Invitrogen). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with oligo(dT) primer and the SuperScript III first strand kit (Invitrogen). A housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), served as a control gene to verify the consistency of reverse transcription. The rat TRPV6 fragment was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-CATCTTCCAGACAGAGGACCC-3′ (1527–1547 of open reading frame, sense) and 5′-TTAGATCTGGTACTCCCAGCCCT-3′ (2184–2162, antisense). For rat Nedd4-2, the primers were 5′-CTGAAGCCCAATGGGTCAG-3′ (2332–2350, sense) and 5′-TTAATCCACACCTTCGAAGCC-3′ (2892–2872, antisense). For rat Nedd4, the primers used were 5′-GACATGGAGTCCGTGGATAGTG-3′ (1984–2005, sense) and 5′-CTAATCAACCCCATCAAAGC-3′ (2670–2650, antisense). Amplification reactions were performed with Premix rTaq (Takara) for 25 cycles using Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY).

Immunofluorescent Staining

Fresh rat intestinal tissues were cut into 0.2–0.3-cm pieces. X. laevis oocytes were washed with Barth's solution 48 h after injection. Tissues and oocytes were fixed in PLP fixative at room temperature for 2 h. After the removal of PLP fixative, the tissues were incubated in PBS solution with 15% sucrose at 4 °C overnight. Tissues and oocytes were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and frozen in −42 °C cold 2-methylbutane. The tissues were sectioned at 6-μm thickness using a Leica Reichert Jung Frigocut 2800 cryostat (Leica Instruments GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

After being fixed in cold acetone at −20 °C for 20 min and washed with PBS (pH 7.5) at room temperature for 15 min, sections were incubated with blocking solution (PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA) at room temperature for 1 h. Sections were then incubated with anti-Nedd4-2 or TRPV6 antiserum (1:100 dilution in blocking solution) in a humidified chamber overnight at 4 °C. After being washed with PBS (pH 7.5) three times for 5 min each, sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC antibody (sc-2012, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (A11012, 1:1,000, Invitrogen) in a humidified chamber at room temperature for 2 h in darkness. Photographs were captured by using a Leica DC500 12-megapixel camera and Leica DMIRB fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) with an FITC filter (blue, 450–490 nm/LP515) for Nedd4-2 and then with a rhodamine filter (green, 515–560 nm/LP590) for TRPV6.

RESULTS

Nedd4-2 Co-localizes with TRPV6 in Rat Intestine

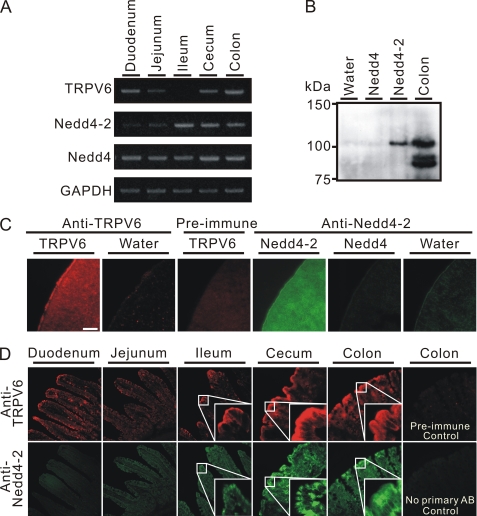

Compared with the well known distribution of Nedd4-2 in the kidney, less is known about its distribution in the intestinal tract. We thus investigated the distribution pattern of Nedd4-2 in the rat intestinal tract and compared it with that of TRPV6. First, we used RT-PCR approach to assess the mRNA level of Nedd4-2, Nedd4, and TRPV6 in rat intestinal tract tissue. As shown in Fig. 1A, Nedd4-2 mRNA was strongly expressed in ileum, cecum, and colon and weakly expressed in duodenum and jejunum. In contrast, the mRNA level of Nedd4, another E3 HECT family member, did not vary significantly along the intestinal tract. TRPV6 was strongly expressed in duodenum, cecum, and colon, weakly expressed in jejunum, and undetectable in ileum (Fig. 1A). This is consistent with the TRPV6 mRNA distribution pattern described previously with Northern blot and in situ hybridization approaches (1). Next, we validated the Nedd4-2 and TRPV6 antisera. As shown in Fig. 1B, the antiserum against Nedd4-2 recognized only Nedd4-2 and not Nedd4 exogenously expressed in X. laevis oocytes by Western blot analysis. A low level of endogenous Nedd4-2 in X. laevis oocytes was detected by this antiserum as well (Fig. 1B). The Nedd4-2 antiserum also recognized a band of identical molecular weight to Nedd4-2 and two bands with lower molecular weight in rat colon lysates (Fig. 1B). These bands probably represent Nedd4-2 and its splice variants. The TRPV6 antiserum, but not the preimmune serum, recognized signals along the plasma membrane and inside oocytes expressing TRPV6 exogenously, but no specific signal was detectable in the control oocytes (Fig. 1C). Nedd4-2 antiserum recognized Nedd4-2 along the plasma membrane and intracellularly, and no specific signal was detectable in Nedd4-expressing and control oocytes (Fig. 1C). Thus, these two antisera were well suited for detecting TRPV6 and Nedd4-2, respectively, by immunofluorescent staining. As previously reported in mouse intestine (2), TRPV6 protein was detected in all of the segments of the rat intestine tested, with the strongest expression in the cecum and colon (Fig. 1D). Although TRPV6 mRNA was not detected by RT-PCR (25 cycles) in the ileum (Fig. 1A), TRPV6 protein was detectable by immunostaining in the same segment (Fig. 1D, top). A similar phenomenon was reported in mice using a different antibody (2). Because we did detect TRPV6 mRNA expression in ileum by RT-PCR at higher cycle numbers (35–40 cycles; data not shown), it is likely that TRPV6 protein was more stable, or the translation efficiency of TRPV6 was high in the ileum. Parallel immunofluorescent staining experiments were performed with Nedd4-2 antiserum using adjacent sections of intestinal tissues (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the level of mRNA (Fig. 1A), Nedd4-2 proteins were strongly expressed in ileum, cecum, and colon, moderately in jejunum, and weakly in duodenum (Fig. 1D). Whereas TRPV6 exhibited staining at the plasma membrane, Nedd4-2 showed both membrane and intracellular distribution. Nedd4-2 and TRPV6 were highly co-localized in the cecum, colon, and ileum (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of Nedd4-2 and TRPV6 in rat intestinal tract. A, RT-PCR results showing expression of TRPV6, Nedd4, and Nedd4-2 in rat intestine at the mRNA level. All PCR experiments were performed for 25 cycles. B, anti-Nedd4-2 antiserum specifically recognized Nedd4-2 but not Nedd4 exogenously expressed in X. laevis oocytes by Western blot analysis. A band with the same size as Nedd4-2 and two bands of lower molecular weight were recognized by this antiserum in rat colon lysate. C, immunofluorescent staining of oocytes injected with cRNAs for TRPV6, Nedd4-2, Nedd4, or water (as controls) with antisera against TRPV6 and Nedd4-2, respectively. TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 antisera recognized TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 expressed in the plasma membrane and cytoplasma of oocytes without specific staining in water or Nedd4 cRNA-injected oocytes. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, immunofluorescent staining of rat intestine tissues with TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 antisera in adjacent sections. TRPV6 antiserum labeled strongly in apical membrane in all segments of rat intestine tested. Nedd4-2 antiserum exhibited weak intracellular staining in duodenum and jejunum and strong staining in ileum, cecum, and colon. Preimmune serum (for control of TRPV6 staining) and secondary antibody alone (for control of Nedd4-2 staining) exhibited no specific staining in colon, respectively. Magnification was ×250 and ×800 for regular and enlarged sections, respectively.

Nedd4-2 Decreases TRPV6 Activity and Protein Level

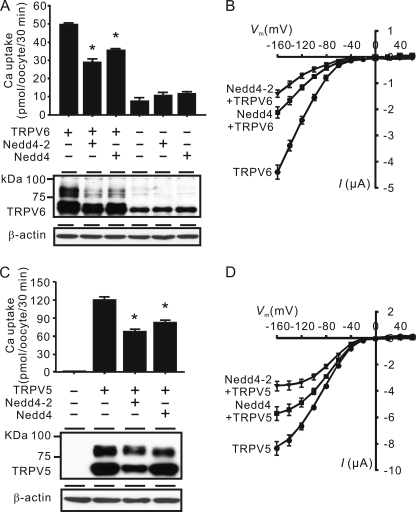

We tested the effects of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake by performing co-expression studies in X. laevis oocytes. When TRPV6 was expressed in oocytes alone, it mediated a robust increase in Ca2+ uptake over the control oocytes (injected with water) at 2 days after injection. When co-expressed with Nedd4-2, TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake was decreased by 47.9 ± 1.4% compared with oocytes expressing TRPV6 alone (Fig. 2A, top). Nedd4, another ubiquitin E3 ligase, also reduced TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake by 28.3 ± 1.8% (Fig. 2A). Measuring TRPV6 Ca2+ current in X. laevis oocytes is hindered by the endogenous Ca2+-activated Cl− channel; however, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, TRPV6 is permeable to Na+, and therefore TRPV6-mediated Na+ current can be used as a measure of TRPV6 activity (12). The Na+ current mediated by TRPV6 was also decreased by Nedd4-2 and, to a lesser extent, by Nedd4, as assessed by voltage clamp (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the reduction in TRPV6 activity, TRPV6 protein level was also decreased by Nedd4-2 and, to a lesser extent, by Nedd4 (Fig. 2A, lower panel). Different N-glycosylated forms of TRPV6 could be detected by Western blot analysis (12, 13); the two bands below 75 kDa represent unglycosylated and core-glycosylated forms, and the group of bands higher than 75 kDa represent complex-glycosylated forms. Nonspecific bands, especially the one that corresponds to the unglycosylated TRPV6, may be detected in control oocytes, although their abundance varied from batch to batch. Nedd4-2 and Nedd4 decreased both groups of TRPV6 bands but had little effect on nonspecific bands (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 2.

Nedd4-2 and Nedd4 decreased Ca2+ uptake, Na+ current, and protein abundance of TRPV6 and TRPV5 in X. laevis oocytes. A, Ca2+ uptake values of control oocytes or oocytes expressing Nedd4-2, Nedd4, TRPV6, or TRPV6 together with Nedd4-2 or Nedd4. Data are presented as means ± S.E. (error bars) of six independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus TRPV6 alone group. Representative Western blot analyses for proteins extracted from different groups using antisera against TRPV6 and β-actin (as loading control) are shown (bottom). B, current-voltage (I-V) plots of Na+-evoked currents in oocytes expressing TRPV6 alone or together with Nedd4-2 or Nedd4. Oocytes expressing Nedd4-2 or Nedd4 exhibited negligible currents similar to water-injected oocytes (not shown). Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of 14 oocytes in each group from four independent experiments. C, Ca2+ uptake in control oocytes (water-injected) or oocytes injected with TRPV5 cRNA alone or together with Nedd4-2 and Nedd4, respectively. Data are presented as means ± S.E. of six independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus TRPV5 alone group. TRPV5 protein level was decreased by Nedd4-2 or Nedd4 (bottom). D, current-voltage plots of Na+-evoked currents in oocytes expressing TRPV5 alone or together with Nedd4-2 or Nedd4. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of 18 oocytes in each group from three independent experiments. All experiments were performed at 2 days after injection of cRNAs.

We also determined the effects of Nedd4-2 and Nedd4 on TRPV5 (Fig. 2, C and D). TRPV5 is another epithelial channel that shares 75% amino acid identity with TRPV6 (35, 36). Unlike TRPV6, TRPV5 is specifically expressed in the distal convoluted tubule and connecting tubule, where it is responsible for the fine tuning of Ca2+ reabsorption (37, 38). In the presence of Nedd4-2 or Nedd4, TRPV5-mediated Ca2+ uptake decreased by 51.9 ± 1.7 or 26.2 ± 4.8% (Fig. 2C, top). TRPV5-mediated Na+ currents were also similarly decreased by Nedd4-2 and Nedd4, respectively (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the decreased activity of TRPV5, the protein level of TRPV5 was decreased by Nedd4-2 and Nedd4 correspondingly (Fig. 2C, bottom). In all cases, Nedd4-2 exhibited stronger inhibitory effects than Nedd4 on both TRPV6 and TRPV5.

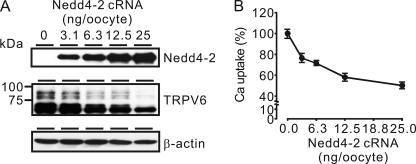

Nedd4-2 inhibited TRPV6 dose-dependently. TRPV6 protein level decreased gradually as the level of Nedd4-2 protein increased (Fig. 3A). Similarly, TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake was further decreased as the level of Nedd4-2 increased (Fig. 3B). We used 12.5 ng/oocyte of Nedd4-2 cRNA in the following experiments because this dosage of Nedd4-2 exhibited a maximal inhibitory effect on TRPV6, although Nedd4-2 exerted a significant effect on TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ influx at a cRNA level as low as 3.2 ng/oocyte (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Nedd4-2 dose-dependently decreased TRPV6 protein abundance (A) and TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake (B). Groups of X. laevis oocytes were injected with 12.5 ng of TRPV6 cRNA with 0, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, or 25 ng of Nedd4-2 cRNA, and Ca2+ uptake experiments were performed 2 days later. Data are presented as a percentage of Ca2+ uptake of the group injected with TRPV6 cRNA alone. Representative Western blot analyses show that TRPV6 protein level decreased as Nedd4-2 protein level increased, and β-actin (loading control) was at a similar level in all of the groups (A). Error bars, S.E.

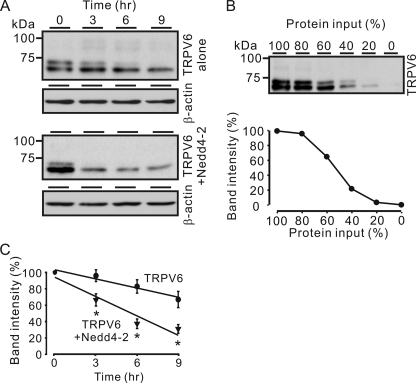

Nedd4-2 Decreases TRPV6 Stability

Because Nedd4-2 can target proteins for degradation, we determined the effects of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 stability. We examined the stability of TRPV6 protein by treating the oocytes with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, for 0, 3, 6, or 9 h at 2 days after injection. Lysates were analyzed by Western blot with the TRPV6 antiserum, and the band densities were quantified by Gel-Pro Analyzer 4.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD). The amount of protein was loaded within a linear range of detection, as determined with different loading levels of lysates from oocytes expressing TRPV6 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). Nedd4-2 significantly increased the TRPV6 degradation rate (Fig. 4A). After cycloheximide treatment for 9 h, 69.6 ± 5.3% of the total TRPV6 was degraded by Nedd4-2, whereas only 33.3 ± 9.9% of TRPV6 protein was degraded in the absence of Nedd4-2 (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Nedd4-2 decreased TRPV6 stability. X. laevis oocytes were injected with 12.5 ng of TRPV6 cRNA alone or together with 12.5 ng of Nedd4-2 cRNA. Two days after injection, the stability of TRPV6 protein was examined by treating the oocytes with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, for 0, 3, 6, or 9 h. A, representative Western blot analyses show the level of TRPV6 proteins at each time point in the presence and absence of Nedd4-2. The level of β-actin determined by Western blotting was used as a control for equal loading. B, assessment of the linear range of TRPV6 band intensity. Oocyte lysates containing TRPV6 protein were loaded at varying levels in different lanes and were run together with samples in A, and the linear range of TRPV6 protein level and band intensity were determined. Shown are a representative Western blot for TRPV6 (top) and the derived relationship of band intensity and TRPV6 protein level (bottom). TRPV6 band intensity is expressed as a percentage of that at 100% input. C, rate of TRPV6 protein degradation in the presence or absence of Nedd4-2. Protein level is expressed as a percentage of band intensity at time 0. Data from seven blots are shown as means ± S.E. (error bars). *, p < 0.05 versus the TRPV6 alone group.

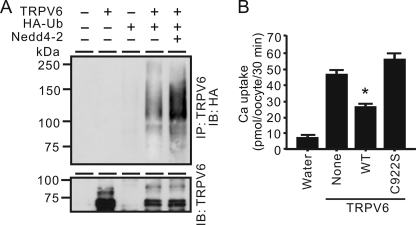

Nedd4-2 Increases Ubiquitination of TRPV6

To confirm the effect of ubiquitin ligase activity of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6, we co-injected HA-ubiquitin and TRPV6 with or without Nedd4-2. Twenty-four hours after injection, oocytes were treated with 25 μm MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, and then harvested 5 h later. After the immunoprecipitation by anti-TRPV6 antibody, ubiquitinated TRPV6 was detected with antibody against HA. Ubiquitination of TRPV6 was dramatically increased by Nedd4-2 (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

The ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of Nedd4-2 was essential to its inhibitory effect on TRPV6. A, ubiquitination of TRPV6 was enhanced by Nedd4-2. Oocytes were injected with cRNA for TRPV6, Nedd4-2, and HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) alone or in combination. Twenty-four hours after injection, oocytes were treated with 25 μm MG132 for 5 h before harvesting. TRPV6 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with a TRPV6 antiserum and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-HA to detect ubiquitinated TRPV6. A Western blot with TRPV6 antiserum is shown at the bottom. B, ligase activity of Nedd4-2 was necessary for the down-regulation of TRPV6. TRPV6 was expressed alone or together with WT Nedd4-2 or Nedd4-2 C922S mutant in oocytes. Data are presented as means ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus TRPV6 alone.

Ligase activity of E3 ligase family members roots in the HECT domain (14), and mutation of a conserved cysteine (amino acid 922 in human Nedd4-2) in this domain results in ubiquitin ligase deficiency (39). To determine the role of Nedd4-2 ubiquitin ligase activity in the degradation of TRPV6, we mutated cysteine 922 to serine (C922S). The effects of wild-type and C922S Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 were compared in the X. laevis oocyte system. The C922S mutant lost its ability to inhibit TRPV6 (Fig. 5B). Thus, the inhibitory effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 was dependent on its ubiquitin ligase activity.

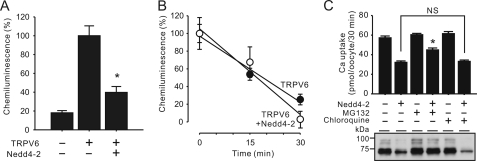

Nedd4-2 Increases the Proteasomal Degradation of TRPV6

The regulation of TRPV6 by Nedd4-2 could be via monoubiquitination and endocytosis or polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. We do not know the nature of the ubiquitination of TRPV6 by Nedd4-2 because both polyubiquitination of a single lysine and monoubiquitination of multiple lysines on TRPV6 can result in the high molecular weight bands in Fig. 5A. We thus evaluated the endocytosis rate of TRPV6 and the pathway for TRPV6 degradation induced by Nedd4-2.

Using an antiserum against part of the first extracellular loop of TRPV6, we were able to detect TRPV6 expressed at the surface of oocytes. In the presence of Nedd4-2, surface-expressed TRPV6 was decreased by 73.5 ± 7.7% (Fig. 6A). The rates of TRPV6 endocytosis were 3.2 ± 0.6 and 2.5 ± 0.3%/min in the presence and absence of Nedd4-2, respectively (Fig. 6B). They were not significantly different. The presence of lysosome inhibitor chloroquine (100 μm) had no effect on the action of Nedd4-2, whereas proteasome inhibitor MG132 (25 μm) alleviated the inhibitory effects of TRPV6 Ca2+ uptake and TRPV6 protein abundance (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Nedd4-2 did not increase the endocytosis TRPV6 but facilitated the proteasomal degradation of TRPV6. A, surface TRPV6 abundance was decreased by Nedd4-2. Oocytes expressing TRPV6 alone or with Nedd4-2 and control oocytes were probed with an antiserum that recognizes the first extracellular loop of TRPV6. The oocytes were then fixed for 1 h at 4 °C and then incubated with an HRP-coupled secondary antibody. Chemiluminescence signals of individual oocytes developed with HRP substrate were detected using a luminometer. The values are expressed as percentages of the chemiluminescence signal level of the TRPV6 alone group. Data from 40–57 oocytes in each group from two batches of oocytes are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars). *, p < 0.01 versus TRPV6 alone group. B, Nedd4-2 did not alter the endocytosis of surface TRPV6. Oocytes were treated with the same maneuver as in A except that they were incubated for 0, 15, and 30 min for endocytosis at room temperature before incubation with secondary antibody. The values are expressed as percentages of the chemiluminescence signal levels at time 0 of the TRPV6 group or the TRPV6 plus Nedd4-2 group. Background values of water-injected control groups were subtracted. Data from 18–61 oocytes in each group from two batches of oocytes are presented as mean ± S.E. C, effects of proteasome inhibitor MG132 and lysosome inhibitor chloroquine on the regulation of TRPV6 by Nedd4-2. Oocytes expressing TRPV6 alone or with Nedd4-2 were incubated with 25 μm MG132 or 100 μm chloroquine for 5 h before Ca2+ uptake and Western blot experiments were performed. Data are presented as means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus the TRPV6 plus Nedd4-2 group; NS, not statistically significant (p > 0.01).

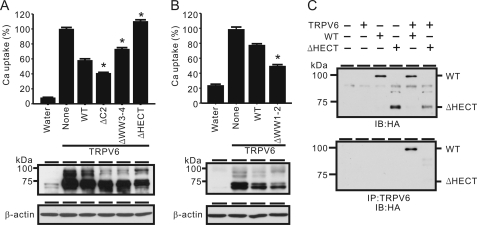

HECT Domain Is Necessary for the Association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6

We next assessed which domain of Nedd4-2 is essential for its action on TRPV6. Nedd4-2 consists of an N-terminal C2 (calcium-dependent lipid binding) domain, followed by four WW domains, which interact with target proteins, and a C-terminal ubiquitin ligase HECT domain. We deleted C2, WW1-2, WW3-4, and HECT domains individually and evaluated the effect of each construct on TRPV6 using the X. laevis oocyte system (Fig. 7, A and B). Deletion of the C2 (amino acids 1–166) or WW1-2 domain (amino acids 194–398) resulted in an enhanced inhibitory effect on TRPV6. Deletion of the WW3-4 domain (amino acids 478–561) slightly alleviated the inhibitory effect, whereas removal of the HECT domain (amino acids 618–955) completely abolished the inhibitory effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6. In fact, TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake was significantly increased by the HECT-deleted Nedd4-2 construct over the control group expressing TRPV6 alone, indicating that this construct may have a dominant negative effect on the endogenous Nedd4-2 because a Nedd4-2-like band was detected in control oocytes (Fig. 1B). It is worth noting that the WW1-2-deleted construct made the oocytes unhealthy at the regular dose of cRNA injection (12.5 ng of cRNA/oocyte). At 1.6 ng of cRNA/oocyte, the action of this construct was much more effective on TRPV6 than the wild-type Nedd4-2 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Assessment of Nedd4-2 domains on TRPV6. A and B, WT Nedd4-2 and Nedd4-2 constructs lacking C2 (ΔC2, without amino acids 1–166), WW1-2 (ΔWW1-2, without amino acids 194–398), WW3-4 (ΔWW3-4, without amino acids 478–561), or HECT (ΔHECT, without amino acids 618–955) were co-injected with TRPV6, and the Ca2+ uptake and TRPV6 protein level were determined 2 days later. A, all cRNAs were injected at 12.5 ng/oocyte; B, WT and ΔWW1-2 were injected at 1.6 ng/oocyte because ΔWW1-2 construct expression made oocytes unhealthy. *, p < 0.01 versus WT plus TRPV6 group. β-Actin was detected by Western blot analysis as a loading control. Only the ΔHECT construct was unable to inhibit TRPV6. C, HECT domain was necessary for the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6. Top, immunoblotting (IB) with the anti-HA antibody showed the expression of HA tagged wild-type and ΔHECT Nedd4-2 constructs. Bottom, HA-tagged Nedd4-2 proteins co-immunoprecipitated (IP) with TRPV6 proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody. HECT domain deletion abolished the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6. Error bars, S.E.

An association with TRPV6 might be necessary for the action of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6. TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 are co-expressed in the intestine (Fig. 1D), and a physical association between TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 is possible although no PY motif was identified in TRPV6. We first evaluated the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6 using a co-immunoprecipitation approach. Oocytes were co-injected with TRPV6 and HA-Nedd4-2 and treated with 25 μm MG132 for 5 h 1 day after injection. The equal expression of HA-Nedd4-2 in the presence and absence of TRPV6 was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 7C). After co-immunoprecipitation with TRPV6 antiserum, HA-Nedd4-2 associated with TRPV6 was detected by an anti-HA antibody (Fig. 7C). In contrast, the same procedure did not reveal an association between the HECT-deleted construct and TRPV6 (Fig. 7C). This indicates that the HECT domain is essential in regulating TRPV6 as well as in the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6.

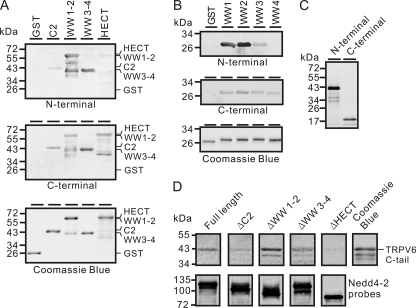

Nedd4-2 Interacts with TRPV6 Directly

To further demonstrate a direct interaction between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6, a Far Western approach was employed. 35S-Labeled N-terminal (amino acids 1–327) and C-terminal (amino acids 578–725) regions of TRPV6 were synthesized in vitro (Fig. 8C). GST fusion Nedd4-2 C2 region (amino acids 1–166, including C2 domain 21–124), WW1-2 region (amino acids 167–438), WW3-4 region (amino acids 439–590), and HECT region (amino acids 591–955, including HECT domain 618–955) were purified and transferred to PVDF membrane and incubated with 35S-labeled N-terminal and C-terminal probes, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8A, the TRPV6 N-terminal probe interacted strongly with WW1-2 and WW3-4 regions and weakly with C2 and HECT regions. The TRPV6 C-terminal probe interacted with all of the domains moderately. By comparing the intensities of bands, it was evident that the N-terminal region had stronger interactions with the WW domains than the C-terminal region, whereas the C-terminal region exhibited more robust interactions with the HECT and C-2 regions than the N-terminal region.

FIGURE 8.

TRPV6 directly interacted with Nedd4-2. A, autoradiography of GST fusion proteins with the Nedd4-2 C2 region (amino acids 1–166, including the C2 domain (amino acids 21–124)), WW1-2 region (amino acids 167–438), WW3-4 region (amino acids 439–590), or HECT region (amino acids 591–955, including the HECT domain 618–955) probed with 35S-labeled TRPV6 N-terminal (top) or C-terminal region (middle). Purified GST fusion proteins stained with Coomassie Blue are shown at the bottom. Note that the bands with lower molecular weights were present in lanes loaded with WW1-2 and HECT fusion proteins (top bands), respectively. The nature of these bands was unknown, but they may represent degraded products. B, autoradiography of individual GST fusion Nedd4-2 WW domains probed with 35S-labeled TRPV6 N-terminal (top) or C-terminal (middle) region. Purified GST fusion WW domains stained with Coomassie Blue are shown at the bottom. C, autoradiography of in vitro synthesized 35S-labeled TRPV6 N-terminal region (1–327 amino acids) and C-terminal region (578–725 amino acids) that were used as probes for A and B. D, autoradiography of GST fusion C-terminal region of TRPV6 (amino acids 597–725; the fusion protein was close to the 43 kDa marker) (top) probed with 35S-labeled Nedd4-2 full-length, ΔC2, ΔWW1-2, ΔWW3-4, and ΔHECT constructs (bottom) described in the legend to Fig. 7. The amounts of different probes were adjusted to the same level for each experiment in A, B, and D based on the band intensity.

To further evaluate the roles of individual WW domains in interacting with TRPV6, Far Western experiments were performed for these WW domains with the TRPV6 N- and C-terminal regions as probes, respectively (Fig. 8B). TRPV6 N-terminal probe interacted strongly with the WW1 and WW2 domains and moderately with the WW3 domain. No interaction was observed between the TRPV6 N-terminal region and the WW4 domain. The TRPV6 C-terminal domain interacted with all of the WW domains moderately (Fig. 8B). The TRPV6 N-terminal region exhibited less robust interaction with individual WW3 and WW4 domains (Fig. 8B) than with the WW3-4 region, indicating that other sequences in the WW3-4 region might also interact with the TRPV6 N-terminal region.

Because the C-terminal region of TRPV6 interacted more strongly with the HECT domain, which is critical for the regulation of TRPV6 by Nedd4-2, we evaluated the interactions between the C-terminal region and the Nedd4-2 constructs lacking C2, WW1-2, WW3-4, and the HECT region, respectively (Fig. 8D). Deletion of the C2 or the WW3-4 region attenuated the interaction; deletion of WW1-2 increased the interaction; deletion of the HECT region greatly reduced the interaction. This is consistent with the co-immunoprecipitation result showing the importance of the HECT domain in its association with TRPV6 (Fig. 7C).

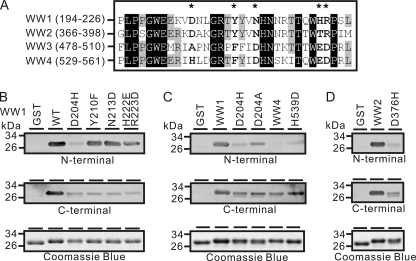

Asp204 Is Essential to the Interaction between WW1 and TRPV6 N-terminal Region

We next set out to identify residues in the WW1 and WW2 domains critical for their interaction with TRPV6 cytoplasmic terminal regions. To this end, the amino acid sequences of four WW domains were aligned (Fig. 9A). Five amino acid residues in WW1 that are conserved in WW1-2 but not in WW3-4 domains were mutated to their corresponding residues in WW3-4. As shown by Far Western analysis, binding between the TRPV6 N-terminal region and the WW1 domain was largely unaffected when Tyr210, Asn213, His222, and Arg223 of WW1 were mutated to their corresponding residues in WW3/4 individually or in combination. However, when Asp204 in WW1 was mutated to the corresponding residue His in WW4, the binding of WW1 to the TRPV6 N-terminal region was greatly reduced (Fig. 9B). In contrast, the interaction between the TRPV6 C-terminal region and WW1 domain was equally reduced by the aforementioned mutations. Similarly, when Asp204 was mutated to the corresponding residue Ala in WW3, WW1 also decreased its ability to bind to TRPV6 N-terminal region (Fig. 9C). Similar to the situation in WW1, the D376H mutation in WW2 also impaired its binding to TRPV6 terminal regions (Fig. 9D). Conversely, mutation of His539 in WW4 to the corresponding residual Asp in WW1 enabled a weak interaction between WW4 and the TRPV6 N-terminal region (Fig. 9C).

FIGURE 9.

Asp204 and Asp376 of Nedd4-2 were critical to the interaction between TRPV6 N-terminal region and WW1 and WW2 domains, respectively. A, sequence alignment of four WW domains of Nedd4-2. *, amino acid residues in WW1 domain that are conserved in WW2 but not in WW3 and WW4 domains. B–D, Far Western analyses of key amino acid residues of WW1 in its interaction with TRPV6 terminal regions. GST fusion WW1, WW2, and WW4 peptides, including the WT and constructs with the indicated mutations, were probed with the 35S-labeled TRPV6 N-terminal region (amino acids 1–327; top) and C-terminal region (amino acids 578–725; middle), respectively. Purified GST fusion WW peptides stained with Coomassie Blue are shown at the bottom. B, D204H mutation in WW1 significantly attenuated the interaction between the TRPV6 N-terminal and WW1 domain. C, D204A mutation in WW1 also attenuated the interaction between the TRPV6 N-terminal region and the WW1 domain. The H539D mutation in the WW4 domain increased the interaction between the TRPV6 N-terminal region and WW4 domain. His539 in WW4 is the counterpart of Asp204 in WW1. D, D376H mutation in the WW2 domain also attenuated the interaction between the TRPV6 N-terminal region and WW2 domain. Asp376 in WW2 is the counterpart of Asp204 in WW1.

Interaction between WW1 and TRPV6 Modulates Nedd4-2 Inhibitory Effect on TRPV6

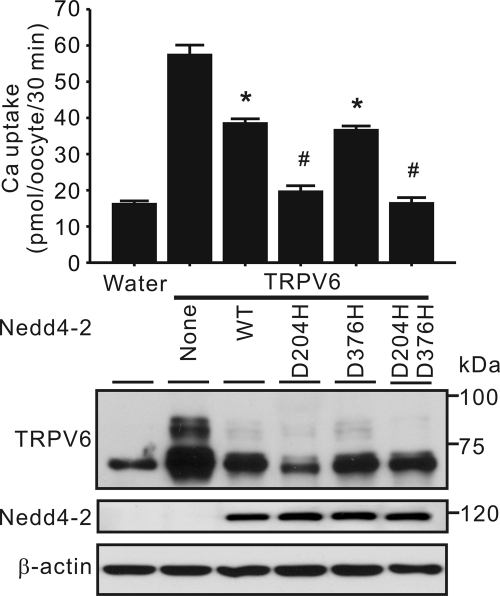

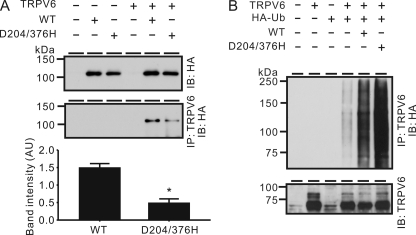

To assess the role of interaction between TRPV6 and WW1 and WW2 domains, wild-type Nedd4-2, D204H, D376H, and D204H/D376H mutants were co-expressed with TRPV6 in X. laevis oocytes, respectively. The D204H mutation in the WW1 domain drastically increased the ability of Nedd4-2 to reduce TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 10). In contrast, the D376H mutation in the WW2 domain did not change the effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 (Fig. 10). Consistent with this, the D204H/D376H double mutant behaved similarly to the D204H mutant (Fig. 10). The association between TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 was decreased by the D204H/D376H double mutations as shown by a co-immunoprecipitation approach (Fig. 11A). Consistent with the Ca2+ uptake result (Fig. 10), ubiquitination of TRPV6 was increased by the D204H/D376H mutant compared with wild-type Nedd4-2 (Fig. 11B).

FIGURE 10.

D204H mutation in Nedd4-2 enhanced its ability to inhibit TRPV6. Top, TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ uptake in oocytes expressing TRPV6 alone or together with WT Nedd4-2, D204H, D376H, or D204H/D376H mutant. Oocytes injected with water (Water) were used as control. Data are presented as means ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus TRPV6 alone group; #, p < 0.01 versus TRPV6 plus wild-type Nedd4-2 group. Representative Western blot analyses using antibodies against TRPV6, Nedd4-2, and β-actin are shown at the bottom.

FIGURE 11.

Nedd4-2 with D204H/D376H double mutations increased TRPV6 ubiquitination without compromising its association with TRPV6. A, association of TRPV6 with HA-Nedd4-2 and HA-Nedd4-2 D204H/D376H in oocytes. Top, immunoblotting (IB) with the anti-HA antibody indicates the equal level of wild-type HA-Nedd4-2 and HA-Nedd4-2 containing the D204H/D376H mutation. HA-Nedd4-2 proteins (wild type or mutant) co-immunoprecipitated with TRPV6 proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody. Bottom, intensity of the co-immunoprecipitated Nedd4-2 band was significantly decreased by the D204H/D376H mutation. Data from four experiments were normalized against band intensity of wild-type or mutant Nedd4-2. *, p < 0.01. AU, arbitrary unit. B, Nedd4-2 D204H/D376H mutant increased the ubiquitination of TRPV6 compared with the wild-type Nedd4-2. Details of the experiments were similar to those described in the legend to Fig. 5A. Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

Degradation is as important as the biosynthesis of a protein in maintaining a functional protein pool in the cell. The degradation of TRPV6 probably plays a role in regulating TRPV6-mediated active Ca2+ absorption. However, little is known about the proteins involved in TRPV6 degradation. In this study, we provided some evidence that the ubiquitin E3 ligase Nedd4-2 plays a role in TRPV6 degradation. We showed that Nedd4-2 is co-expressed with TRPV6 in the rat intestinal epithelial cells. TRPV6 activity was reduced by Nedd4-2 due to the decreased TRPV6 protein abundance. Decreased TRPV6 stability and increased TRPV6 ubiquitination were also observed in the presence of Nedd4-2. The interaction between the HECT domain and the C-terminal region of TRPV6 is essential for the association between the two proteins and the action of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6. In addition, we identified Asp204 as a critical amino acid residue in the WW1-TRPV6 interaction, which is involved in controlling the efficiency of TRPV6 protein ubiquitination and degradation by Nedd4-2.

Nedd4-2 has been shown to be expressed in human small intestine (24). We further described the distribution of Nedd4-2 in various segments of the rat intestinal tract at both mRNA and protein levels. In the small intestine, both Nedd4-2 mRNA and protein levels increase gradually from the proximal to the distal small intestine, with the highest level in the ileum. This is opposite to TRPV6, which shows a decreasing abundance from proximal to distal small intestine. In contrast, the Nedd4 mRNA level is relatively constant along the small intestine. The opposite pattern of TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 expression gradients in the small intestine may further strengthen the high level expression of TRPV6 in the proximal intestine by exerting a minimal effect in this segment. In contrast to the small intestine, both TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 are very abundant in cecum and colon at both mRNA and protein levels. Therefore, TRPV6 in the large intestine is more likely subjected to regulation by Nedd4-2. The complementary distribution pattern between TRPV6 and Nedd4-2 and the stronger effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 suggest a more significant role of Nedd4-2 in regulating TRPV6, although this does not exclude Nedd4 as a potentially important regulator of TRPV6 and TRPV5.

The effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 appears to be similar to those of Nedd4-2 on other membrane transporters, receptors, and ion channels (14). As an archetypal E3 ligase, Nedd4-2 is well known for regulating cell surface stability of the channels by attaching ubiquitin chains to them, followed by endocytosis and lysosomal or proteasomal degradation (14–16). Under the regulation of Nedd4-2, TRPV6 is ubiquitinated and, in turn, degraded via an MG132-sensitive proteasome pathway. We found no evidence that this process occurs only to TRPV6 proteins in the plasma membrane because the rate of TRPV6 endocytosis is not significantly affected by Nedd4-2. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that Nedd4-2 can mediate monoubiquitination on TRPV6, these data suggest that Nedd4-2 mediates polyubiquitination of TRPV6 and facilitates its degradation via a proteasome pathway.

WW domains mediate most of the binding of the Nedd4-like family members with their substrates. The well known binding motif of WW domains within their target proteins, such as ENaC (17), Notch (40), Snap3 (41), KCNQ1 (28), or TrkA neurotrophin receptor (26), is the proline-based recognition sequence PPXY (PY motif). The binding of PY motif to Nedd4-2 mostly occurs at the WW3 and WW4 domains (42, 43). However, not every protein directly binds with the WW domain of Nedd4-type ubiquitin E3 ligases through a PY motif. A chemokine receptor, CXCR4, which has no PY motif, binds with the WW1 or WW2 domains of E3 ubiquitin ligase AIP4 via a 324/325 double serine in its C-terminal region (44). PTEN even interacts with the C2 and HECT domains of Nedd4 (45). Nedd4-2 interacts with TRPV6 with different domains, including the C2, WW, and HECT domains.

Although all domains of Nedd4-2 tested exhibited interactions with either the N-terminal, the C-terminal, or both regions of TRPV6, the HECT domain appears to be the most critical domain for the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6, as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation and Far Western approaches. The C2 domain exhibited a significant interaction with the C-terminal region of TRPV6. The increased inhibition of TRPV6 by the ΔC2 construct (Fig. 7A) suggests that the effect of Nedd4-2 on TRPV6 may be Ca2+-dependent. Most Nedd4-2-targeted proteins interact with its WW3-4 domains. Interestingly, our study revealed that the N-terminal region of TRPV6 interacts with WW1 and WW2 domains, a situation similar to the interaction between CXCR4 and AIP4 (44). However, the interaction between WW1-2 domains and TRPV6 is not indispensable for the association between Nedd4-2 and TRPV6, because other domains, such as the HECT and C2 domains, significantly interact with the TRPV6 C-terminal region.

Our study revealed an important role of the WW1-2 domains in Nedd4-2 function and regulation. WW1-2 exhibited the strongest interaction with the TRPV6 N-terminal region, although it also interacted moderately with the TRPV6 C-terminal region. The removal of WW1-2 or the disruption of the interaction between WW1-2 and TRPV6 terminal regions by the D204H/D376H mutation each resulted in an increase in inhibitory effects on Ca2+ uptake and protein level of TRPV6 (Figs. 7 and 10). A decrease in association with TRPV6 was observed in the D204H/D376H mutant (Fig. 11); however, this does not necessarily imply a reduction in the interaction between HECT domain and TRPV6. On the contrary, the removal of the WW1-2 region increased the interaction between the TRPV6 C-terminal region and Nedd4-2 possibly through the HECT domain (Fig. 8D). The increased TRPV6 ubiquitination by the D204H/D376H mutant is consistent with an increase in efficiency of Nedd4-2 action on TRPV6. Thus, WW1 and WW2 probably act as a switch. When they bind to TRPV6 terminal regions, the interaction between HECT domain and TRPV6 C-terminal region is limited, and therefore, TRPV6 is ubiquitinated at a low speed; when WW1 and WW2 disassociate from TRPV6 terminal regions, the interaction between the HECT domain and the TRPV6 C-terminal region increases. This turns on the turbo mode of Nedd4-2 and, as a consequence, the efficiency of TRPV6 ubiquitination increases. In addition, the WW1-2 region may also regulate the E3 ligase activity of Nedd4-2 not specifically to TRPV6 because we have noticed that the expression of the ΔWW1-2 construct and, to a lesser extent, the D204H/D376H mutant alone rendered the oocytes unhealthy, although the situation worsened when TRPV6 was co-expressed.

Our data suggest that Nedd4-2 may regulate TRPV6 ubiquitination and degradation at different rates by regulating their interaction. The physiological cues that may strengthen or weaken these interactions are yet to be identified. Like Nedd4-2, Nedd4 appears to inhibit TRPV6 albeit to a lesser extent. Both Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 also inhibit TRPV5. The physiological significance of these regulations warrants further studies.

Acknowledgment

We thank Phillip Chumley for editorial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01DK072154 (to J.-B. P.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Greater SE Affiliate Grant 09GRNT2160024 (to J.-B. P.). Part of this work was presented in abstract form (46).

- ENaC

- epithelial Na+ channel

- HECT

- homology to the E6-associated protein C terminus

- C2

- calcium-dependent lipid binding

- MBS

- modified Barth's solution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peng J. B., Chen X. Z., Berger U. V., Vassilev P. M., Tsukaguchi H., Brown E. M., Hediger M. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22739–22746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhuang L., Peng J. B., Tou L., Takanaga H., Adam R. M., Hediger M. A., Freeman M. R. (2002) Lab. Invest. 82, 1755–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood R. J., Tchack L., Taparia S. (2001) BMC Physiol. 1, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer M. B., Watanuki M., Kim S., Shevde N. K., Pike J. W. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1447–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cromphaut S. J., Dewerchin M., Hoenderop J. G., Stockmans I., Van Herck E., Kato S., Bindels R. J., Collen D., Carmeliet P., Bouillon R., Carmeliet G. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13324–13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianco S. D., Peng J. B., Takanaga H., Suzuki Y., Crescenzi A., Kos C. H., Zhuang L., Freeman M. R., Gouveia C. H., Wu J., Luo H., Mauro T., Brown E. M., Hediger M. A. (2007) J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 274–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Cromphaut S. J., Rummens K., Stockmans I., Van Herck E., Dijcks F. A., Ederveen A. G., Carmeliet P., Verhaeghe J., Bouillon R., Carmeliet G. (2003) J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1725–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Graaf S. F., Hoenderop J. G., Gkika D., Lamers D., Prenen J., Rescher U., Gerke V., Staub O., Nilius B., Bindels R. J. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1478–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Q., Hoefs S., van der Kemp A. W., Topala C. N., Bindels R. J., Hoenderop J. G. (2005) Science 310, 490–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha S. K., Ortega B., Kurosu H., Rosenblatt K. P., Kuro-O M., Huang C. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9805–9810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Böhmer C., Palmada M., Kenngott C., Lindner R., Klaus F., Laufer J., Lang F. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 5586–5590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W., Na T., Peng J. B. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F1472–F1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Y., Cong P., Williams S. R., Zhang W., Na T., Ma H. P., Peng J. B. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 375, 225–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staub O., Rotin D. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86, 669–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glickman M. H., Ciechanover A. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82, 373–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicke L., Schubert H. L., Hill C. P. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 610–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staub O., Dho S., Henry P., Correa J., Ishikawa T., McGlade J., Rotin D. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2371–2380 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staub O., Gautschi I., Ishikawa T., Breitschopf K., Ciechanover A., Schild L., Rotin D. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 6325–6336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schild L., Lu Y., Gautschi I., Schneeberger E., Lifton R. P., Rossier B. C. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2381–2387 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansson J. H., Nelson-Williams C., Suzuki H., Schild L., Shimkets R., Lu Y., Canessa C., Iwasaki T., Rossier B., Lifton R. P. (1995) Nat. Genet. 11, 76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araki N., Umemura M., Miyagi Y., Yabana M., Miki Y., Tamura K., Uchino K., Aoki R., Goshima Y., Umemura S., Ishigami T. (2008) Hypertension 51, 773–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staub O., Yeger H., Plant P. J., Kim H., Ernst S. A., Rotin D. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272, C1871–C1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi H., Grenier J., Fournier A., Labrie C. (2003) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 210, 51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmada M., Dieter M., Speil A., Böhmer C., Mack A. F., Wagner H. J., Klingel K., Kandolf R., Murer H., Biber J., Closs E. I., Lang F. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 287, G143–G150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fotia A. B., Ekberg J., Adams D. J., Cook D. I., Poronnik P., Kumar S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28930–28935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arévalo J. C., Waite J., Rajagopal R., Beyna M., Chen Z. Y., Lee F. S., Chao M. V. (2006) Neuron 50, 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekberg J., Schuetz F., Boase N. A., Conroy S. J., Manning J., Kumar S., Poronnik P., Adams D. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12135–12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jespersen T., Membrez M., Nicolas C. S., Pitard B., Staub O., Olesen S. P., Baró I., Abriel H. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 74, 64–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmada M., Dieter M., Boehmer C., Waldegger S., Lang F. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321, 1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieter M., Palmada M., Rajamanickam J., Aydin A., Busjahn A., Boehmer C., Luft F. C., Lang F. (2004) Obes. Res. 12, 862–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng J. B., Brown E. M., Hediger M. A. (2001) Genomics 76, 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y., Ferguson W. B., Peng J. B. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292, F545–F554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Na T., Zhang W., Jiang Y., Liang Y., Ma H. P., Warnock D. G., Peng J. B. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F1042–F1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Traweger A., Fuchs R., Krizbai I. A., Weiger T. M., Bauer H. C., Bauer H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2692–2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng J. B., Chen X. Z., Berger U. V., Vassilev P. M., Brown E. M., Hediger M. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28186–28194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoenderop J. G., van der Kemp A. W., Hartog A., van de Graaf S. F., van Os C. H., Willems P. H., Bindels R. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8375–8378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loffing J., Loffing-Cueni D., Valderrabano V., Kläusli L., Hebert S. C., Rossier B. C., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J., Kaissling B. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281, F1021–F1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoenderop J. G., van Leeuwen J. P., van der Eerden B. C., Kersten F. F., van der Kemp A. W., Mérillat A. M., Waarsing J. H., Rossier B. C., Vallon V., Hummler E., Bindels R. J. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1906–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamynina E., Debonneville C., Bens M., Vandewalle A., Staub O. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennings M. D., Blankley R. T., Baron M., Golovanov A. P., Avis J. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29032–29042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stawiecka-Mirota M., Pokrzywa W., Morvan J., Zoladek T., Haguenauer-Tsapis R., Urban-Grimal D., Morsomme P. (2007) Traffic 8, 1280–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omerovic J., Santangelo L., Puggioni E. M., Marrocco J., Dall'Armi C., Palumbo C., Belleudi F., Di Marcotullio L., Frati L., Torrisi M. R., Cesareni G., Gulino A., Alimandi M. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 2849–2862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan J. A., Lewis M. J., Nikko E., Pelham H. R. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2429–2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhandari D., Robia S. L., Marchese A. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1324–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X., Shi Y., Wang J., Huang G., Jiang X. (2008) Biochem. J. 414, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W., Na T., Peng J.-B. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 998.16 (Abstract) [Google Scholar]