Abstract

Objectives

To quantify the potential impact of mass rape on HIV incidence in seven conflict-afflicted-countries (CACs), with severe HIV epidemics, in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Design

Uncertainty analysis of a risk equation model.

Methods

A mathematical model was used to evaluate the potential impact of mass rape on increasing HIV incidence in women and girls in: Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, southern Sudan and Uganda. The model was parameterized with data from UNAIDS/WHO and the US Census Bureau’s International Data Base. Incidence data from UNAIDS/WHO were used for calibration.

Results

Mass rape could cause ~five HIV infections per 100,000 females per year in the DRC, Sudan, Somalia and Sierra Leone, double that in Burundi and Rwanda, and quadruple that in Uganda. The number of females infected per year due to mass rape is likely to be relatively low in Somalia and Sierra Leone, 127 (median: Inter-Quartile-Range (IQR) 55–254) and 156 (median: IQR 69–305), respectively. Numbers could be high in the DRC and Uganda: 1,120 (median: IQR 527–2,360) and 2,172 (median: IQR 1,031–4,668), respectively. In Burundi, Rwanda and Sudan numbers are likely to be intermediate. Under extreme conditions 10,000 women and girls could be infected per year in the DRC, and 20,000 women and girls in Uganda. Mass rape could increase annual incidence by ~ 7% (median: IQR 3–15).

Conclusions

Interventions and treatment targeted to rape survivors during armed conflicts could reduce HIV incidence. Support should be provided both on the basis of human rights and public health.

Keywords: Risk equation model, Mass rape, Incidence, HIV, conflict-affected countries, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Systematic mass rape during armed conflict [1–3] now occurs so frequently that it has been recognized, and legally defined, by the United Nations as a weapon of war [4]. The highest number of armed conflicts occur in Sub-Saharan Africa [5] where many Conflict-Afflicted-Countries (CACs) have a high prevalence of HIV [6]. Consequently it has been hypothesized by several authors [7–11], that mass rape may be increasing HIV epidemics in some CACs. This hypothesis has recently been questioned by Spiegel et al. [12] who have assessed the link between mass rape and HIV prevalence by conducting a detailed review of the literature. In their review they included studies from seven CACs in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), southern Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Burundi [12]. Despite the fact that data show these countries have a high prevalence of HIV [6] and that wide-scale rape has occurred, the authors found no data to show rape has increased HIV prevalence [12]. Their finding has recently been corroborated by Amena et al. [13] who used a risk equation model to estimate the potential impact of mass rape on HIV prevalence in the same seven CACs investigated by Spiegel and colleagues [12]. Their risk modeling shows that even under the most extreme circumstance the impact of mass rape on prevalence could be expected to be negligible (i.e., they determined that prevalence would only increase by 0.023%) [13]. However Amena and colleagues did not assess the potential impact of mass rape in CACs on increasing HIV incidence. Here, we use risk equation modeling to investigate the potential impact of mass rape on increasing HIV incidence (as well as prevalence) in the DRC, southern Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Burundi.

To inform our modeling we obtained parameter estimates from the literature. Reliable statistics on mass rape are difficult to obtain, but surveys have revealed that the number of women who are raped during conflicts can be extremely high. In Sierra Leone 9% of women reported war-related sexual assaults [14], while in Liberia 15% of women reported rape or sexual coercion [15]. It has been estimated hundreds of thousands of women were raped during the genocide in Rwanda in the early 1990’s [16, 17]. Widespread sexual violence has been reported during the current conflict in the DRC [3, 18–21]; for example, the organization Malteser International registered more than 20,000 female rape survivors during the three year period 2005–2007 [19]. For the time period November 2008 to March 2009 it has been estimated over a thousand women were raped each month in the DRC [22].

The probability that a woman raped during an armed conflict will become infected with HIV depends on whether the rapist is infected with HIV or not, and the probability that HIV is transmitted during the rape. The probability the rapist is infected can be expected to be related to the prevalence of HIV in armed combatants. Several studies have found that in CACs with severe HIV epidemics, the HIV prevalence among the military forces can be significantly greater than in the general population. For example, a recent study of 21 African countries found, on average, HIV prevalence within the military was six times as high as that of males aged 15–24 in the general population [23]. In Uganda, the HIV prevalence among military was 10 times higher than among males aged 15–24 in the general population [23]. The probability that HIV is transmitted during an act of rape is unknown. However, this transmission probability is likely to be higher than for consensual sex as mass rape often involves violence and genital trauma including widely reported cases of vaginal fistulae [21, 24, 25]. For consensual sex between heterosexuals in Africa, the per act probability of HIV transmission (given that the partner is infected) has been estimated to be 0.0009 (range: 0.0006–0.0012) and to rise to 0.0559 (range: 0.0044–0.1073) if Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) are present [26]. Notably, the highest rate of STIs occur in sub-Saharan Africa [27] and armed combatants often have high STI rates [28, 29]. Taken together, the available data suggest that the probability that a woman raped during conflict would become infected with HIV could be fairly high.

Methods

We used the static risk equation model (Equation 1) developed by Amena and colleagues [13] to estimate the number of new HIV infections that could occur in the DRC, southern Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Burundi (over one year) due to mass rape. Following Anema et al. [13] we assume that the population at-risk of rape is females aged between 5 and 49 years old. Equation 1 shows the number of uninfected women and girls (5 to 49 years old) that could become infected with HIV due to mass rape during armed conflicts ( ) is calculated as the product of the number of women and girls (5 to 49 years old) who are currently uninfected (X5–49), the proportion of the female population (5 to 49 years old) who are raped (r), the prevalence of HIV among the assailants (Pr) and the average probability of transmission per act of rape (βar):

| (1) |

The HIV prevalence among assailants (Pr) is assumed to be higher than the HIV prevalence in the rest of the male population (P), such that then Pr = α × P or α = Pr/P where α, is called the prevalence ratio, and is assumed to be greater than, or equal to, one.

To make calculations using Equation 1 we estimated parameters from data. We used data from UNAIDS/WHO [30] to determine HIV prevalence (i.e., P) in the DRC, southern Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Burundi. We then estimated the number of uninfected women and girls aged between 5–49 years old (i.e., X5–49) in each of the seven CACs by subtracting the number of prevalent infections (determined from UNAIDS/WHO data [30]) from the total number of females aged 5 to 49 years old (determined from demographic data in the United States (US) Census Bureau’s International Data Base [31]). For the remaining parameters in Equation 1 we explored, for comparative purposes, the same ranges that Amena et al. [13] used in their analyses. Hence we assumed 1%–15% of the female population (5 to 49 years old) could be raped (i.e., r varied from 0.01 to 0.15), the prevalence of HIV in assailants would be one to eight times greater than in the general male population (i.e., α varied from 1 to 8) and the average probability of HIV transmission per act of rape (βar) varied between 0.0028–0.032.

We used Equation 2 to calculate country-specific annual HIV incidence due to consensual sex among uninfected women and girls aged 15 to 49 years old ( ). This incidence is calculated as the product of several factors: the number of uninfected women and girls aged 15 to 49 (X15–49), the HIV prevalence in the general male population (P), the average probability of HIV transmission per partnership (βp) and the average number of new consensual sex partners per year (c):

| (2) |

where βp = 1−(1−βac)n, n is the number of sex acts per consensual partnership per year and βac is the average probability of HIV transmission per consensual sex act. We estimated the value for X15–49, as we had for X5–49, using HIV prevalence data from UNAIDS/WHO [30] and demographic data from the US Census Bureau’s International Data Base [31]. We assumed that the probability of transmitting HIV during one act of rape is equal to or greater than during one act of consensual sex. Therefore we set βac to be the lowest value of βar (i.e., βac was set to 0.0028). We calibrated our risk equation model by setting ranges for c and n; calibration occurred when the country-specific HIV incidence (in times of no conflict) estimated by the model matched the UNAIDS estimate of incidence. At calibration c ranged from 0.5 to 1 and n ranged from 20 to 100.

We then divided Equation 1 (which specifies the number of HIV infections due to mass rape of 5 to 49 year olds during conflict) by Equation 2 (which specifies the number of HIV infections due to consensual sex in 15 to 49 year olds in peace time) to determine the percentage increase in the annual number of HIV infections in women and girls due to mass rape during conflict:

| (3) |

To obtain quantitative estimates using the above expression we used uncertainty analysis and sampled ranges on the following parameters: the proportion of the population who are raped, the prevalence ratio, the average probability of HIV transmission per act of rape, the average number of consensual partnerships per year and the average number of sex acts per consensual partnership per year. We assume that - in any particular year - the average probability of transmission per act of rape can be regarded as approximately constant. We make this assumption because the average value of this probability depends upon the level of infectivity averaged over all the perpetrators in the population. Over one year the infectiousness of some of these individuals may change (e.g., some individuals will move from primary to chronic infection), but the infectiousness of the majority of these individuals is unlikely to change substantially over this time period. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that - over a year - the average probability of transmission per act of rape remains approximately constant. However, if we were modeling the impact of rape over a period of several years it would be necessary to include variability in infectiousness over time (i.e., to include variation in βar over time).

We then sampled all of the parameter ranges using Latin Hypercube Sampling [32] and used this sample to run 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations. We therefore made 10,000 estimates for each of the seven CACs.

Results

UNAIDS/WHO data [30] show that HIV prevalence and incidence in the general populations of the seven CACs we are investigating is high, with the lowest prevalence occurring in Somalia and the highest in Uganda (Table 1). Notably, calibration ensured that the incidence estimated by our model is in close agreement with the UNAIDS/WHO incidence data; compare column 5 in Table 1 with column 2 in Table 2. In terms of incidence rates we estimate that mass rape could cause a median of five new HIV infections per 100,000 women per year in the DRC, southern Sudan, Sierra Leone and Somalia, double that number in Burundi and Rwanda, and quadruple that number in Uganda (Table 2).

Table 1.

Country-specific demographic and HIV prevalence and incidence data; *HIV prevalence calculated using data from UNAIDS/WHO [30] and the United States Census Bureau’s International Data Base [31]. Prevalence is calculated for individuals aged between 5 and 49 years old.

| Country | Population size [30] | Prevalence in men (%) | Prevalence in women (%) | HIV incidence [39] per 100,000 individuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi | 8,508,000 | 2.0–3.5 | 1.4–2.5 | 100–200 |

| DRC | 62,636,000 | 1.5–2.0 | 1.1–1.3 | 100–200 |

| Rwanda | 9,725,000 | 2.1–2.6 | 2.9–3.7 | 200–300 |

| Sierra Leone | 5,866,000 | 1.7–3.1 | 1.2–2.2 | 200–300 |

| Somalia | 8,699,000 | 0.2–0.7 | 0.1–0.2 | <100 |

| Sudan | 38,560,000 | 1.3–2.7 | 0.7–1.8 | 100–200 |

| Uganda | 30,884,000 | 6.7–8.2 | 4.4–5.5 | 300–1000 |

Table 2.

Estimates from risk equation modeling of the potential impact of mass rape on HIV incidence and prevalence.

| Country | Incidence without mass rape | Incidence due to mass rape | % increase in incidence due to mass rape | % increase in prevalence due to mass rape |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per 100,000 individuals median (IQR) | Per 100,000 Individuals median (IQR) | median (IQR) | median (IQR) | |

| Burundi | 214 (144–291) | 9 (4–17) | 7 (3–15) | 0.009 (0.004–0.017) |

| DRC | 132 (91–176) | 5 (2–10) | 6 (3–13) | 0.005 (0.002–0.010) |

| Rwanda | 259 (177–349) | 10 (5–20) | 6 (3–14) | 0.010 (0.004–0.020) |

| Sierra Leone | 186 (123–249) | 7 (3–14) | 6 (3–13) | 0.007 (0.003–0.014) |

| Somalia | 97 (65–146) | 4 (2–8) | 6 (3–13) | 0.004 (0.001–0.008) |

| Sudan | 135 (89–187) | 5 (2–11) | 6 (3–15) | 0.005 (0.002–0.011) |

| Uganda | 537 (375–730) | 20 (10–44) | 7 (3–14) | 0.019 (0.009–0.042) |

Estimates for column 2 are for women and girls aged 15 to 49 years old; estimates for columns 3, 4 and 5 are for women and girls aged 5 to 49 years old. IQR represents InterQuartile Range.

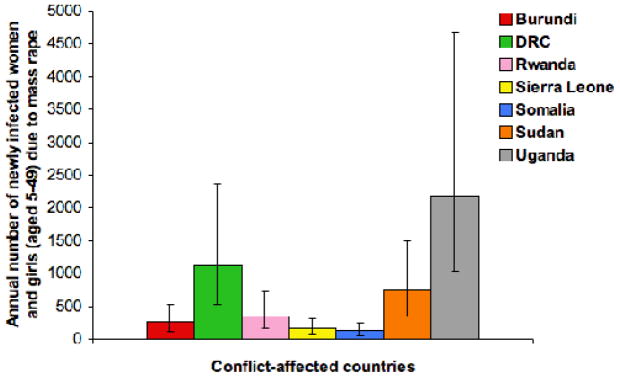

Due to differences in population sizes, we estimate that the annual number of women and girls (aged 5–49) that could become infected with HIV due to mass rape varies substantially among the seven CACs (Figure 1). For two of these countries our estimates show that this number would be relatively low; for Somalia 127 (median: Inter-Quartile-Range (IQR) 55–254) new HIV infections and for Sierra Leone 156 (median: IQR 69–305) new HIV infections (Figure 1). However in the DRC and Uganda our estimates show the numbers could be high; for the DRC 1,120 (median: IQR 527–2,360) new HIV infections and for Uganda 2,172 (median: IQR 1,031–4,668) new HIV infections. For Burundi, Rwanda and Sudan the numbers are intermediate (Figure 1). In total, we estimate that 4,948 (median; IQR 2,043–10,329) women and girls could be infected with HIV due to mass rape each year in the seven CACs we have investigated.

Figure 1.

Estimates of the number of women and girls (aged 5–49) who could become infected in a year as a consequence of mass rape during armed combat. Estimates were made using an uncertainty analysis of the risk model (shown in Equation 1); results from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations are plotted. Vertical bars represent median values and vertical error bars represent inter-quartile ranges.

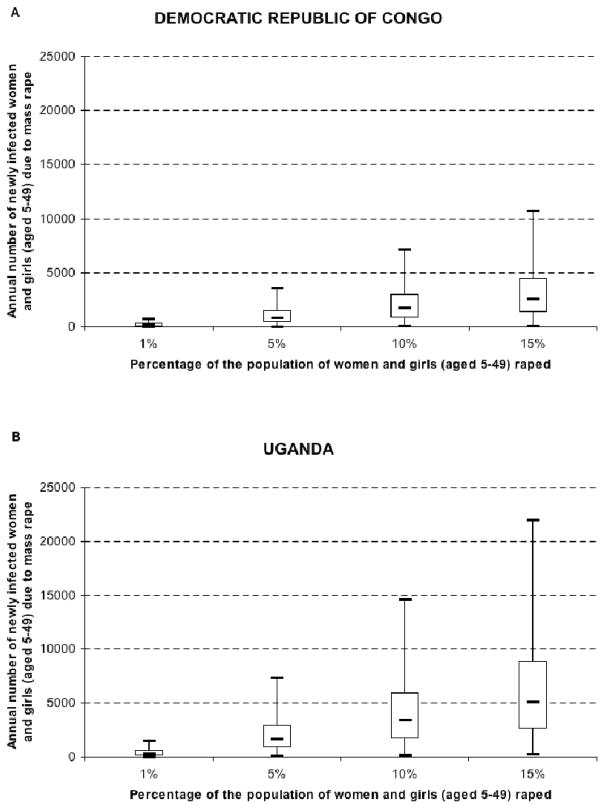

Figure 2 shows, for the DRC (A) and Uganda (B), the estimates from the uncertainty analysis of the annual number of new HIV infections in women and girls (aged 5–49) due to mass rape. The graphs in Figure 2 were constructed by varying all the parameters in the risk equation and then stratifying the estimates on the basis of the prevalence of rape. This Figure illustrates that the distribution of the model-based estimates is highly skewed. The distribution is skewed as parameter ranges are sampled during the uncertainty analysis in order to account for heterogeneities in transmission risk due to the presence of STIs or other cofactors [33, 34]. The skewed distribution in estimates also reflects the sampled variability in the prevalence ratio; the prevalence of HIV in assailants relative to the prevalence in the general population will substantially affect the influence of mass rape on increasing incidence. Notably, Figure 2 shows that under extreme conditions 10,000 women and girls could be infected per year in the DRC, and 20,000 women and girls could be infected per year in Uganda.

Figure 2.

Box plots (median, inter-quartile range, minimum and maximum) showing estimates of the number of women and girls (aged 5–49) who could become infected with HIV in a year as a consequence of mass rape versus the prevalence of rape: (A) the Democratic Republic of Congo (B) Uganda. Estimates made using an uncertainty analysis of the risk model (Equation 1); results from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations are plotted.

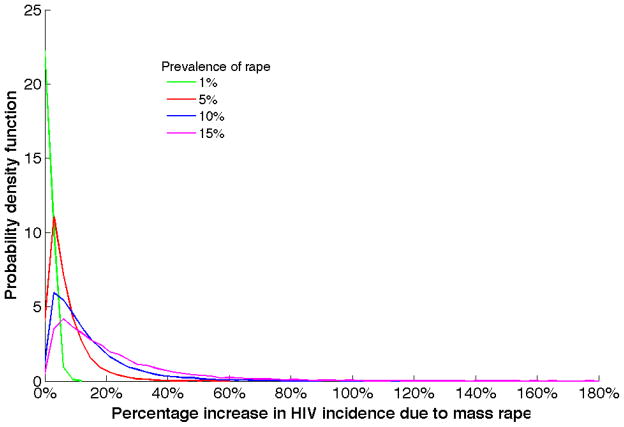

Our analysis shows that mass rape could have a significant effect on increasing incidence, but would have a negligible impact on prevalence (Table 2). Specifically we calculate that the median increase in incidence would be 6 to 7%, but the median increase in prevalence would be less than 0.02%. Figure 3 shows that relationship between the increase in incidence and the prevalence of rape. Our calculations show that in CACs where 15% of girls and women are raped the annual HIV incidence could increase by a median of 15% (Figure 3). However, the increase in incidence under these conditions could be significantly greater; 25% of the Monte Carlo simulations in our uncertainty analysis show that incidence could be increased by more than 27% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Probability density function of the percentage increase in incidence due to mass rape during armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Estimates stratified by the prevalence of rape. Estimates made using an uncertainty analysis of the risk model (Equation 1); results from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations are plotted.

Discussion

The impact of mass rape on HIV epidemics in CACs is currently unknown. It is difficult to capture incidence data in contexts of crisis, thus there is a paucity of data availalable for assessing the consequences of mass rape on HIV incidence. We have addressed this problem by using a quantitative risk assessment framework to assess the potential effect of mass rape on HIV incidence. We have also assessed the potential effect on HIV prevalence. Our risk modeling indicates that even under extreme conditions mass rape is likely to have a negligible impact on HIV prevalence. Our results with respect to the potential effect of mass rape on HIV prevalence are in agreement with those previously published by Amena et al. [13] who calculated that prevalence would increase by only 0.023% even if: 15% of the female population was raped, prevalence of HIV in the group of assailants was eight times greater than in the general population, and the transmission probability of HIV per act of rape was four times greater than the transmission probability per act of consensual sex [13]. However Amena et al. [13] focused only on HIV prevalence, whereas we have assessed the potential impact of mass rape on HIV incidence as well as prevalence. Notably, our results show that although mass rape in CACs may not significantly affect prevalence it could significantly affect incidence. Whilst our analysis is unlikely to have produced precise estimates of the impact of mass rape on incidence it demonstrates the potential magnitude of the effect. Consequently we can conclude that thousands of women and girls could be infected with HIV each year due to mass rape in CACs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, it should be note that the true value for the probability of transmission per act of rape could be as high as 0.1073 if STIs are present [26]. If the probability of transmission is this high then the number of women and girls who are infected due to mass rape each year could be three times higher than we have estimated.

Our analysis has only examined the consequence of mass rape on HIV incidence due to direct infection. Mass rape also indirectly increases HIV incidence through at least two other mechanisms: women who become infected through rape can transmit HIV to their future male partners and some survivors of rape may be infected with an STI (other than HIV) that increases their susceptibility to HIV. Moreover, our analysis does not include the fact that mass rape leads to unwanted pregnancies and subsequent HIV infections due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). Clearly, more sophisticated mathematical models that include these additional effects in order to more adequately assess the impact of mass rape in CACs on HIV epidemics are needed. Since we have not included these effects in our current analyses our estimates are likely to be under-estimates of the effect of mass rape on increasing incidence (and ultimately prevalence) of HIV epidemics.

We stress that the type of modeling exercise that we have conducted in this study is only designed to model epidemiological processes. Such exercises cannot evaluate the impact of physical damage due to violent assault nor the unimaginable long-term suffering and psychological scarring due to rape [35]. In addition, modeling cannot be used to quantify the fact that survivors of sexual violence are often stigmatized and rejected by their partners and family [35]. Stringent protocols for supporting and treating women and girls subjected to rape in conflict situations are urgently needed. These protocols should include immediate medical care for traumatic genital injury caused by forced sex and treatment for STIs. However, it may not always be possible to implement such protocols. Even raising the issue of rape in conflict situations can itself prove hazardous. For example, in 2006, a Norwegian humanitarian organization was expelled from South Darfur following allegations of false reporting of rape cases and “promoting a foreign agenda” [36]. Although 250,000 people had been killed in the conflict and a further 300,000 displaced a government spokesman for South Darfur stated that no rape cases had occurred. A year previously, two members of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) had been arrested following an MSF report that detailed the treatment they had provided to hundreds of rape survivors in local hospitals [35]. Until 2005, women in Darfur could be threatened with imprisonment if they reported rape and health care staff risked incarceration for treating them. While this policy has now changed, it has left a legacy of mistrust of the state, with women reluctant to report rape and health care workers cautious about treating rape survivors [36].

Clearly medical interventions are needed, on the basis of human rights, to ameliorate the experiences of women caught in the trauma of armed conflict and exposed to mass violence and rape. In our analysis we have extended this perspective. By taking a quantitative risk assessment approach we have shown (for the first time) that mass rape during armed conflicts may significantly increase HIV incidence. Our results have extremely important health policy implications. They indicate that HIV prevention and treatment strategies targeted to rape survivors could potentially have an impact on reducing HIV incidence in CACs. We recommend that interventions for prevention to reduce MTCT and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and terminations of unwanted pregnancies should be made widely available to survivors of rape in regions of armed conflict. During conflicts many women can be forced to migrate and seek shelter in camps, often separating them from social and safety networks and exposing them to sexual violence [37, 38]. Focusing targeted interventions in refugee camps may be an effective means for reaching rape survivors. Further research is needed to improve understanding of the impact of mass rape on HIV epidemics and to assist in the design of evidence-based medical interventions for rape survivors in CACs. With implementation of targeted, effective policies and service interventions it may be possible to reduce HIV incidence during armed conflicts. Consequently, medical interventions and support for rape survivors during armed conflicts should be provided on both the basis of human rights and public health.

Acknowledgments

VS designed the study, carried out the computations, interpreted the results and contributed to writing the manuscript. YH interpreted the results and contributed to writing the manuscript. SB conceived and designed the study, interpreted the results, and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors saw and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding statement: SB and VS are grateful for the financial support of the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant RO1 AI041935). SB also thanks the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for funding. YH did not receive any funding for this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Card C. Rape as a weapon of war. Hypatia. 1996;11:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagan J, Rymond-Richmond W, Palloni A. Racial targeting of sexual violence in Darfur. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1386–1392. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omba Kalonda JC. Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo: impact on public health? Med Trop (Mars) 2008;68:576–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The United Nations Security Council. Resolution. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];Women and peace and security. 2008 1820:2008. Available at: http://www.un.org/Docs/sc/unsc_resolutions08.htm.

- 5.Uppsala University. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];Uppsala Conflict Data Program, UCDP Database. Available at: www.ucdp.uu.se/database.

- 6.UNAIDS. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];AIDS epidemic update. 2009 Available at: http://data.unaids.org:80/pub/Report/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en.pdf.

- 7.Ellman T, Culbert H, Torres-Feced V. Treatment of AIDS in conflict-affected settings: a failure of imagination. Lancet. 2005;365:278–280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankins CA, Friedman SR, Zafar T, Dtrathdee SA. Transmission and prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in war settings: implications for current and future armed conflicts. AIDS. 2002;16:2245–2252. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock NB, Duale S, Brown LF, Mathys E, O’maonaigh HC, Abul-Husn NL, Elliott S. Conflict and HIV: A framework for risk assessment to prevent HIV in conflict-affected settings in Africa. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2004;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills EJ, Singh S, Nelson BD, Nachega JB. The impact of conflict on HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:713–717. doi: 10.1258/095646206778691077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker JU, Theodosis C, Kulkarni R. HIV/AIDS, conflict and security in Africa: rethinking relationships. J Int AIDS Soc. 2008;11:3. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel PB, Bennedsen AR, Claass J, Bruns L, Patterson N, Yiweza D, Schilperoord M. Prevalence of HIV infection in conflict-affected and displaced people in seven sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;369:2187–2195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anema A, Joffres MR, Mills E, Spiegel PB. Widespread rape does not directly appear to increase the overall HIV prevalence in conflict-affected countries: so now what? Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amowitz LL, Reis C, Lyons KH, Vann B, Mansaray B, Akinsulure-Smith AM, et al. Prevalence of war-related sexual violence and other human rights abuses among internally displaced persons in Sierra Leone. JAMA. 2002;287:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swiss S, Jennings PJ, Aryee GV, Brown GH, Jappah-Samukai RM, Kamara MS, et al. Violence against women during the Liberian civil conflict. JAMA. 1998;279:625–629. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donovan P. Rape and HIV/AIDS in Rwanda. Lancet. 2002;360 (Suppl):s17–18. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs OCHA. . Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Conflict: A Framework for Prevention and Response. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];2008 Available at: http://ochaonline.un.org/OCHAHome/InFocus/SexualandGenderBasedViolence/AFrameworkforPreventionandResponse/tabid/5929/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- 18.Taback N, Painter R, King B. Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. JAMA. 2008;300:653–654. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner B, Benner MT, Sondorp E, Schmitz KP, Mesmer U, Rosenberger S. Sexual violence in the protracted conflict of DRC programming for rape survivors in South Kivu. Confl Health. 2009;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakabi W. Sexual violence increasing in Democratic Republic of Congo. Lancet. 2008;371:15–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onsrud M, Sjoveian S, Luhiriri R, Mukwege D. Sexual violence-related fistulas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Security Council. Twenty-seventh report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];2009 Available at: http://ochaonline.un.org/OCHAHome/InFocus/SexualandGenderBasedViolence/AFrameworkforPreventionandResponse/tabid/5929/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- 23.Ba O, O’Regan C, Nachega J, Cooper C, Anema A, Rachlis B, Mills EJ. HIV/AIDS in African militaries: an ecological analysis. Med Confl Surviv. 2008;24:88–100. doi: 10.1080/13623690801950260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jewkes R. Comprehensive response to rape needed in conflict settings. Lancet. 2007;369:2140–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60991-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukwege DM, Nangini C. Rape with extreme violence: the new pathology in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:553–563. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];2001 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/en/who_hiv_aids_2001.02.pdf. [PubMed]

- 28.Luque Fernandez MA, Bauernfeind A, Palma Urrutia PP, Ruiz Perez I. Frequency of sexually transmitted infections and related factors in Pweto, Democratic Republic of Congo. Gac Sanit. 2004;22:29–34. doi: 10.1157/13115107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mabey D, Mayaud P. Sexually transmitted diseases in mobile populations. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:18–22. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UNAIDS. UNAIDS/WHO/UNICEF Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV and AIDS, 2008 Update. [Accessed on 17 April 2010]; Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/Epidemiology/epifactsheets.asp.

- 31. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];United States Census Bureau’s International Data Base. Available at: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/country.php.

- 32.Blower SM, Dowlatabadi H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission—An HIV model, as an example. Int Stat Rev. 1994;62:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auvert B, Buve A, Ferry B, Carael M, Morison L, Lagarde E, et al. Ecological and individual level analysis of risk factors for HIV infection in four urban populations in sub-Saharan Africa with different levels of HIV infection. AIDS. 2001;15 (Suppl 4):S15–30. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auvert B, Buve A, Lagarde E, Kahindo M, Chege J, Rutenberg N, et al. Male circumcision and HIV infection in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15 (Suppl 4):S31–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Médecins Sans Frontières. [Accessed on 17 April 2010];Shattered lives: Immediate medical care vital for sexual violence victims. 2009 Available at http://www.msf.org.uk/UploadedFiles/Shattered_Lives_Report_200903043128.pdf.

- 36.Sudan Tribune. Nov 20, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Global Coalition on Women and AIDS. Information Bulletin Series no.2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Sexual violence in conflict settings and the risk of HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlachovà M, Biason L. Women in an insecure world: violence against women: facts, figures and analysis. Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merson MH, O’Malley J, Serwadda D, Apisuk C. The history and challenge of HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:475–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]