Abstract

Cellular uptake of cobalamin (Cbl) occurs by endocytosis of transcobalamin (TC) saturated with Cbl by the transcobalamin receptor (TCblR/CD320). The cell cycle associated over expression of this receptor in many cancer cells, provides a suitable target for delivering chemotherapeutic drugs and cytotoxic molecules to these cells while minimizing the effect on the normal cell population. We have used monoclonal antibodies to the extracellular domain of TCblR to deliver saporin conjugated secondary antibody to various cell lines propagating in culture. A molar ratio of 2.5:10nM of primary:secondary antibody concentration was identified as the lowest concentration needed to produce the optimum cytotoxic effect. The effect was more pronounced when cells were seeded at lower density suggesting lack of cell division in a fraction of the cells at higher density as the likely explanation. Cells in suspension culture such as K562 and U266 cells were more severely affected than adherent cultures such as SW48 and KB cells. This differential effect of the anti TCblR-saporin antibody conjugate and the ability of an anti TCblR antibody to target proliferating cells was further evident by the virtual lack of any effect on primary skin fibroblasts and minimal effect on bone marrow cells. These results indicate that preferential targeting of some cancer cells could be accomplished via the TCblR receptor.

Keywords: Transcobalamin, CD320, monoclonal antibodies, vitamin B12

Introduction

Cellular uptake of vitamin B12 (cobalamin, Cbl) is mediated by the transcobalamin receptor (TCblR/CD320) on the plasma membrane that specifically binds transcobalamin (TC), a plasma protein saturated with Cbl (1, 2, 3). The TCblR protein is structurally related to the LDL receptor family with two LDLR type A domains separated by a cysteine-rich CUB like domain and contains a single transmembrane region followed by a short cytoplasmic tail (4). The expression of this receptor appears to be cell cycle associated with highest expression in actively proliferating cells and is substantially down regulated in quiescent cells (5, 6, 7). This differential expression of the receptor serves to provide optimum delivery of the vitamin to cells during the early phase of DNA synthesis. This process ensures adequate functioning of Cbl dependent enzymes, especially the methionine synthase that is essential for recycling of methyl folate to generate folates needed for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis (8). The more proliferative a cell, the higher the need for folates and Cbl and this need for Cbl is met by the increased expression of TCblR in cancer cells that may have inherently lost the ability to stop dividing and differentiate. Selective targeting of cancer cells for destruction by delivering drugs and toxins preferentially to these cells has been the ultimate objective of cancer therapy. The search for tumor specific markers and the strategies to utilize these in cancer therapy have been pursued for decades with mixed results. This can be attributed to multiple factors that include the lack of specificity of the target antigen, cellular events that can alter the targeting and to the complex and diverse nature of cancer itself. Recently, potent toxins such as ricin A chain, gelonin, saporin, cholera toxin, diphtheria toxin, pseudomonas exotoxin have been utilized to target these molecules to tumors as conjugates of antibodies or as chimeric proteins with varying success (9, 10). We have utilized the cell cycle associated expression of TCblR to deliver saporin, an inhibitor of ribosomal assembly (11) to cancer cells using monoclonal antibodies to the extra cellular domain of TCblR.

Materials & Methods

Monoclonal antibodies were generated to the recombinant extracellular domain of TCblR expressed in HEK 293 cells and purified as described previously (4). Purified antibodies were used to study the delivery of saporin conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Advanced Drug Targeting) to various cell lines maintained in culture. We used K562 (ATCC CCL 243) human erythroleukemia cells and U266 (ATCC TIB 196) human myeloma that propagate as a suspension culture; SW48 (ATCC CCL-231) human colon adenocarcinoma cells and KB (ATCC CCL-17) human epidermoid carcinoma that propagate as adherent cells and human embryonic kidney stem cells, HEK 293 (ATCC CRL-1573). These cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection Center, Rockville, MD and have been identified by karyotyping. Second and third passage cells were frozen in aliquots and used for these studies. MCH 064, MCH 065 and RF peripheral skin fibroblast cultures in passage 9 – 12 were from The Repository for Mutant Human Cell Strains, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Canada. Fresh human bone marrow mononuclear cells were obtained from Lonza, Walkersville, MD. In addition, HEK 293 cells stably transfected with the cDNA for TCblR in pcDNA 3.1 to overexpress the receptor were used (HEK293TR). These cells have about a ten fold higher expression of TCblR constitutively driven by the CMV promoter and therefore TCblR expression is not cell cycle associated. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. The primary antibody was incubated with the Saporin conjugated secondary antibody for 1h at room temperature to form the complex prior to use in the culture.

Binding specificity of the monoclonal antibodies

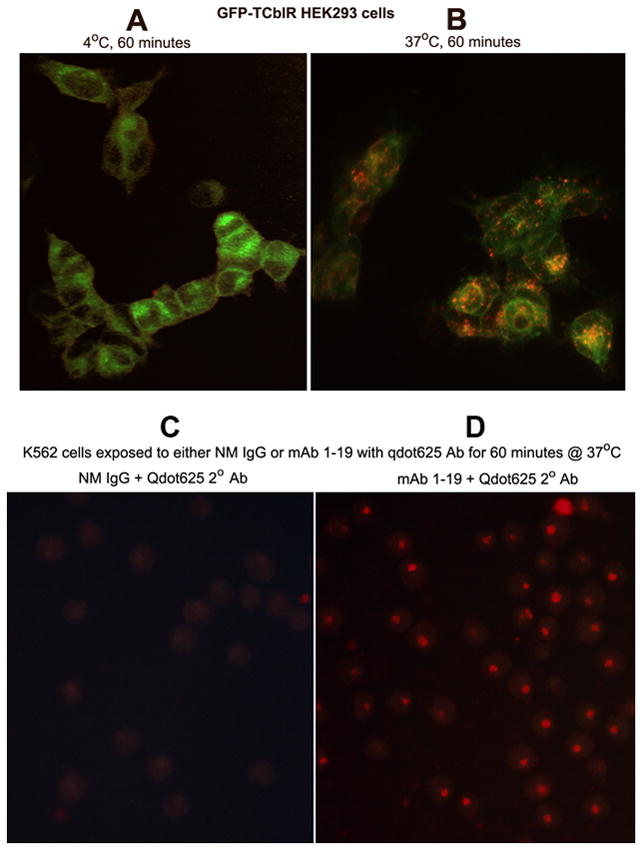

Binding and internalization of antibody directed to TCblR was determined in HEK293 cells that were engineered to express a Green Fluorescent Protein tag in the cytoplasmic end of TCblR. For this determination, mAb1-25 was pre-incubated with quantum dot (qdot) 625 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary Ab (Invitrogen) for 60 minutes to form a complex and then incubated with cells in culture.

The specificity of monoclonal antibody binding was tested in K562 cells that expressed the native TCblR. The binding and internalization of mAb1-19-qdot 625 complex was determined at 4°C and 37°C and normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control.

Determination of optimum concentration of primary antibody

To determine the optimum concentration of mAb for the in vitro cell-kill studies, mAb1-25 was pre-incubated with Saporin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary Ab at a 1:1 molar ratio for 60 minutes to form a complex. Various concentrations of this mAb/Sap-Ab complex (0.1 pM to 50 nM) were incubated with 10,000 SW48 (colon carcinoma) or K562 (erythroleukemia) cells in 96 well culture plates for 72 hours and viable cells were quantified by the MTS assay (Promega).

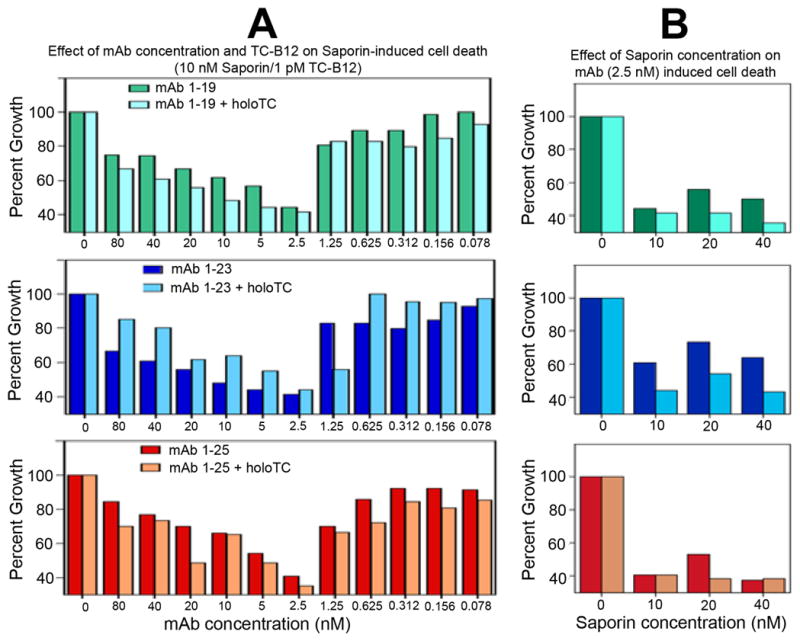

Determination of optimum ratio of mAb to Saporin-Ab

For using the anti TCblR antibodies as carrier of Saporin into cells via TCblR, the optimum ratio of primary monoclonal antibody to Saporin conjugated secondary antibody was determined. SW48 colon carcinoma cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in 96 well culture plates. In one set of experiments, the concentration of primary mAb was varied from 0.078 to 80 nM while the concentration of secondary Ab was kept constant at 10 nM. In another set of experiments, the concentration of the primary mAb was kept constant at 2.5 nM and the concentration of Saporin-Ab was varied from 10 to 40 nM. Cell viability was determined after 72 hours by the MTS assay.

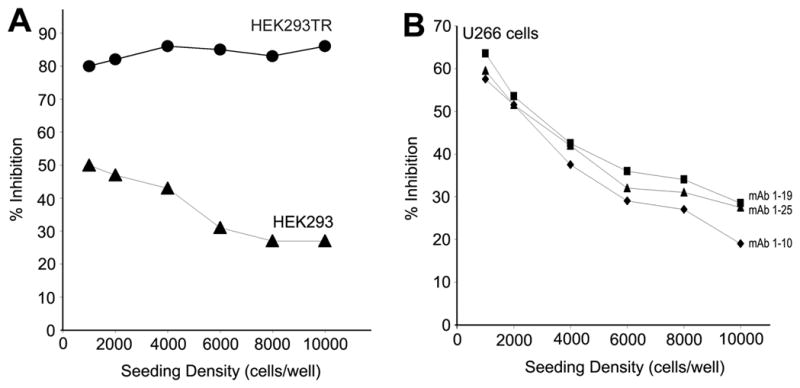

Effect of cell seeding density on efficacy of mAb/Saporin-Ab complex

Seeding density defines the proliferative phase of the culture and therefore cells seeded at lower density would replicate longer until the cell population reaches confluency. Since TCblR expression is highest in actively dividing cells, we tested cell lines at seeding densities varying from 1000–10000 cells /well with three different primary antibodies at 2.5 nM mAb and 10 nM Saporin-Ab concentration.

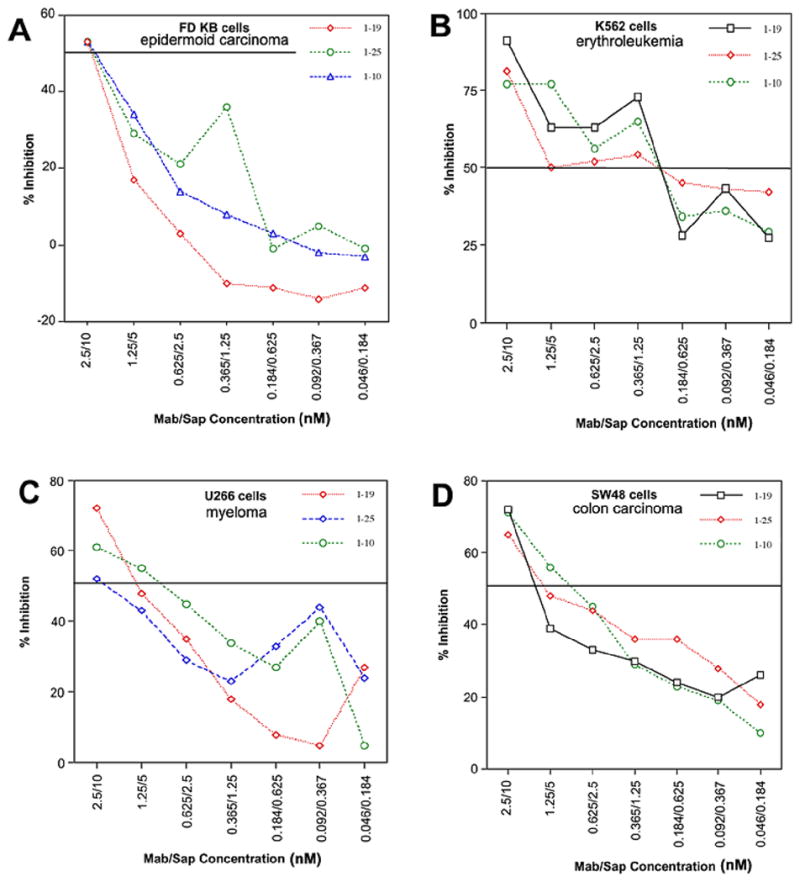

Determination for mAb/Saporin-Ab concentration required for inhibiting cell growth by 50% (IC50)

Since the toxic effect of Saporin-Ab was more pronounced in cell cultures seeded at lower density, the IC50 determinations were done with cells seeded at 1000 cells/well in 96 well plates, a mAb/Saporin-Ab ratio of 1:4 and a primary antibody concentration range of 0.046 – 2.5 nM. Viable cells were determined by the MTS assay after 96 hours in culture.

Specificity of TCblR pathway for delivering the Saporin-Ab toxin

The specificity of the TCblR-mediated pathway for internalization of the mAb-Saporin-Ab toxin complex was determined by adding soluble receptor to the culture medium. The soluble receptor would compete with the cell surface receptor for the antibody and this would reduce the Ab-toxin available for cellular uptake resulting in a decrease in percent inhibition. For this experiment, SW48 cells were seeded in 96 well plates at 2000 cells/ well and the amount of mAb/Saporin-Ab used was equivalent to the IC50 concentration.

Specificity of anti-TCblR mAb for delivering the Saporin-Ab toxin

A100 fold excess primary mAb or normal mouse IgG was added to the incubation medium containing a mAb/Saporin-Ab concentration of 2.5/10 nM. A decrease in the anti-TCblR mAb/Saporin-Ab induced inhibition of cell growth should be observed when excess primary Ab is present since the ratio of Sap-Ab labeled primary mAb to unlabelled primary mAb should be lower and this increases the probability of unlabelled mAb binding to TCblR. The addition of normal mouse IgG should also result in a decrease in cell-kill since the secondary Sap-Ab would also bind to the normal mouse IgG and this complex cannot bind to TCblR.

Results

Cells stably transfected to express a chimeric TCblR with GFP tagged to the cytoplasmic end of the receptor show discrete membrane associated fluorescence. As shown in Figure 1A, binding of the mAb1-25-qdot 625red complex at 4°C was restricted to surface receptors as indicated by mostly membrane associated diffused fluorescence dispersed throughout the periphery of the cell. Binding and internalization of the mAb1-25-qdot 625red complex bound to TCblR occurred at 37°C as indicated by segregation of receptors to discrete regions in the membrane as well as the cytoplasm indicated by colocalization of the red and green fluorescence (1B). Similar binding and internalization was observed with mAb1-19-qdot 625red complex when incubated with K562 cells expressing normal levels of non-GFP native TCblR (1D). The specificity of binding and internalization was confirmed by substituting normal mouse IgG for the primary antibody and incubating with K562 cells which failed to show any binding and internalization of qdot 625red (fig 1C).

Figure 1.

Binding and uptake of mAb 1–19 in HEK293TR cells expressing GFP tagged TCblR (A & B) and in K562 cells expressing native TCblR (C & D). The mAb was tagged with goat anti mouse Qdot 625red nano particles. Figure shows membrane expression of TCblR-GFP and surface binding of Qdot 625red indicated by low level evenly scattered fluorescence (A) and internalization of Qdot 625red indicated by brighter segregated red-green/yellow fluorescence at 37°C. Uptake of Qdot 625red in K562 cells incubated with anti TCblR mAb (D) and lack of uptake when normal mouse IgG is substituted for the mAb (C).

Initial titration of the mAb/Sap-Ab complex at 1:1 molar ratio incubated with SW48 or K562 cells for 72 hours indicated that a primary Ab concentration of 2–5 nM was adequate for testing the ability of these antibodies to deliver Saporin toxin to cancer cells In order to determine the optimum ratio of Saporin conjugated secondary antibody to the anti TCblR primary mAb, in the first set of experiments the Saporin-Ab concentration was kept constant at 10 nM and the concentration of primary mAb was varied from 0.078 to 80 nM. In the second set of experiments, the concentration of the primary mAb was kept constant at 2.5 nM and the concentration of Saporin-Ab was varied from 10 to 40 nM. All three anti-TCblR mAbs tested yielded similar results with 2.5 nM concentration of the primary mAb as most effective in inhibiting cell growth (Figure 2A). The addition of 3.7 nM holo-TC to the culture, did not have a significant effect on the outcome even though minor differences were observed due to TC-Cbl competing with the antibody for uptake. The concentration of TC-Cbl used was in excess over the normal TC-Cbl of 0.5 – 1.5 nM in plasma. Increasing the concentration of Saporin-Ab did not produce any increase in cell death (Figure 2B). Thus a mAb concentration of 2.5 nM and a Saporin-Ab concentration of 10 nM (i.e. a mAb/Saporin-Ab ratio of 1:4) appeared optimum for delivering antibody-toxin into cells via the TCblR pathway.

Figure 2.

The optimum ratio of the anti TCblR mAb to the Saporin conjugated secondary mAb was determined by varying the concentration of the mAb from 0.078 – 80 nM at a constant concentration of Saporin conjugated secondary antibody of 10nM (A) and by varying the concentration of secondary mAb from 10 – 40 nM at a primary mAb concentration of 2.5 nM (B). maximum effect was observed at mAb/ Sap-Ab concentration of 2.5/10 nM (1:4 ratio).

HEK 293 cells stably transfected to over express TCblR were highly sensitive to mAb-Saporin-Ab, resulting in a >90% inhibition of cell growth. The expression of TCblR in these cells is driven by the CMV promoter and is not dependent on the cell cycle or proliferative state of the cell. The relationship between TCblR expression and the effect of the mAb-Saporin conjugate was evident when normal HEK293 cells and HEK293TR cells over expressing TCblR were seeded at varying densities and exposed to the mAb-Saporin. Whereas the effect of the toxin decreased with increasing cell density for normal HEK293 cells, greater than 80% of the HEK293TR cells were killed at all cell densities (figure 3A). Thus the effectiveness of the toxin was directly related to the level of receptor expression. For all cell lines tested where the receptor expression is related to the proliferative state of the cells in culture, most effect was observed when seeded at lower density as shown for U266 cells in figure 3B. All three mAbs tested, yielded similar results. For comparing the effective delivery of toxin, IC50 determinations were done and are shown in figure 4 for two suspension cultures and two adherent cell lines. For most cell lines, the IC50 was in the 0.625 – 2.5 nM range for the primary mAb concentration.

Figure 3.

A. Effect of cell seeding density and receptor expression on Saporin induced cell death. Cells seeded at lower density showed the highest effect due to higher proliferative activity and the native receptor expression coupled to this activity. In constitutively high TCblR expressing HEK293TR cells, the effect of Saporin was independent of seeding cell density. B. Seeding density dependent inhibition of cell growth of U 266 myeloma cells in suspension culture.

Figure 4.

Determination of IC 50 for two adherent (A & B) and two suspension (C & D) cultures. The primary mAb to Saporin secondary antibody concentration was maintained at 2.5:10 nM.

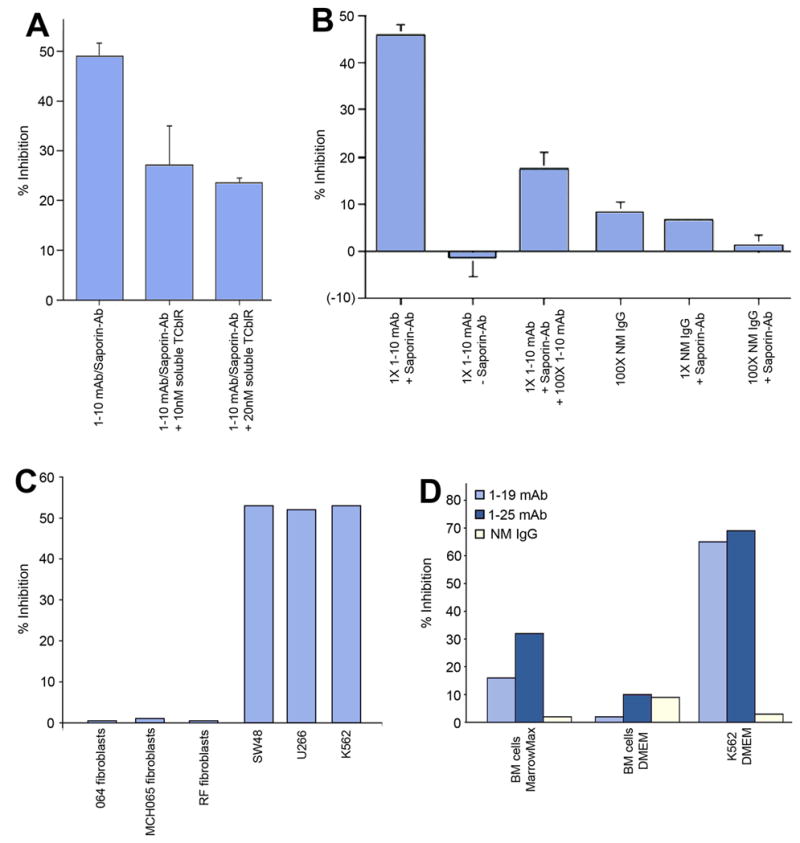

The specificity of the TCblR pathway was evident from the decreased effect of the toxin when soluble recombinant TCblR was added to the culture medium. Soluble receptor in the culture medium would compete with the cell surface receptor for the antibody and reduce the Ab-toxin available for cellular uptake, resulting in a decrease in percent inhibition as shown in Figure 5A. The specificity of mouse anti-TCblR mAb for delivering the Saporin-Ab toxin was determined by adding either a 100-fold excess primary mAb or normal mouse IgG to the incubation medium. The inhibition of cell growth seen with anti-TCblR mAb1-10/Saporin-Ab was decreased when either excess primary Ab or normal mouse IgG was added. Primary mAb or normal mouse IgG in the absence of Saporin-Ab had no effect on cell growth (Figure 5B). The growth inhibitory effect of TCblR mAb/Saporin-Ab complex appeared to be specific for tumor cell lines, since three different normal human fibroblast cell lines were not inhibited under the identical culture conditions (Figure 5C). The effect on the bone marrow cells appeared to be considerably less when maintained in DMEM compared to Marrowmax medium but far less than the inhibition observed with many tumor cell lines ( Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The specificity of mAb/Saporin-Ab for TCblR was demonstarted by adding purified soluble TCblR to the culture medium, which resulted in decreased availability of mAb/Saporin to receptors on cells and decreased cell death (Panel A). The inhibitory effect of the mAb-Saporin Ab also decreased when excess primary mAb or normal mouse IgG was added to the culture. No inhibition of cell growth was observed when saporin-Ab was withheld or when primary mAb was withheld (Panel B). Values are expressed as percentage of maximum inhibition shown in the first bar. Panel C shows the specificity of mAb-Sap-Ab for cancer cells and lack of toxicity to primary skin fibroblasts. Panel D shows the effect of mAb-SapAb on human bone marrow cells in vitro.

Discussion

Since the identification of cancer-specific antigens and monoclonal antibodies, the goal in therapeutic developments has been to target the cancer cell for destruction without affecting the normal cellular components. This simple concept has proven to be difficult to execute because of the complex and diverse nature of cancer and biological adaptations that escape treatment modalities. It is now recognized that multipronged approaches tailored to specific cancers and tissue types may be needed to succeed in devising treatments that are cancer specific and less toxic. The therapeutic potential of monoclonal antibodies as immune modulators or as carriers of drugs or toxins is being explored as engineered antibodies that are well tolerated are being developed (12, 13). The use of potent toxins such as ricin, cholera toxin, gelonin and saporin if targeted specifically to cancer cells could be highly effective in destroying these cells (9, 10, 14, 15). This requires a tumor cell specific target antigen that the monoclonal antibody can recognize and deliver the toxin to the cell. Numerous receptors have been explored as target antigens with some degree of success (16, 17). However these antigens are also expressed on normal cells and therefore selective targeting of cancer cells is dictated primarily by differential expression of the target receptor. The generalized toxicity of the conjugate will depend on the number of receptors expressed on each cell type and therefore, receptors that are highly expressed in normal cells, even though over expressed in cancer cells, are not likely to be selective and effective targets because normal cells would also internalize sufficient toxin for destruction. The ideal target antigen would have to be tumor specific or be expressed at such low levels in normal cells that would render the dose ineffective. This same receptor if over expressed in cancer cells would provide a target antigen that could be selective for the tumor cells. The TCblR expression is fairly low with only a few thousand receptors expressed in actively replicating cells during the S phase of the cell cycle (5, 6, 7). Due to the proliferative nature of neoplastic cells this expression is 5 to 10 fold up regulated and sustained in certain cancer cells. This differential expression appears to be sufficient to provide the selectivity needed to target the cancer cell for destruction while sparing the normal cell population. This conclusion is based on the decreased effect on cells seeded at higher density which do not divide at the same rate as cells seeded at lower density and the virtual sparing of normal cells which did divide but failed to internalize sufficient toxin. Because of the essential role of Cbl in the recycling of folate, in Cbl deficiency cells fail to replicate as indicated by the megaloblastic changes in the bone marrow (8). Blocking Cbl uptake into cells by monoclonal antibodies to TC has been used to demonstrate the utility of this strategy in cancer therapy (18, 19). An antibody to TCblR that blocks the binding of TC-Cbl can also prevent cellular uptake of TC-Cbl and could be used to block Cbl uptake into cancer cells. These approaches, even though feasible with virtually no direct systemic toxicity, are not very practical because of the long treatment schedule required to deplete intracellular Cbl. The use of the TC-TCblR pathway to deliver toxins and drugs provides the dose needed to rapidly destroy highly proliferative tumor cells. The cell cycle associated TCblR expression and the high level of expression in certain cancer cells vs normal cells provides selectivity and specificity demanded of this targeting strategy. In utilizing these antibodies in vivo in humans, bone marrow toxicity is a potential concern. The low toxicity observed for these cells in DMEM and slightly higher effect seen in Marrowmax medium is related to proliferation and differentiation of marrow cells in the latter. On average, TCblR expression in embryonic stem cells is similar to that observed in skin fibroblasts (4). Thus the proliferative state of the cells and TCblR expression would dictate marrow toxicity. Even though the effect on the marrow in vitro appears low, far greater toxicity is likely in vivo. Decreasing cell surface receptors by pre dosing with B12 or with antibody without toxin are strategies likely to decrease cell surface receptors to minimize toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant R01DK064732 and by KYTO Biopharma, Toronto, CA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration: Patent application WO2007/117657 A2

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Tavassoli M, Jacobsen DW. Receptor binding and internalization of immobilized transcobalamin II by mouse leukaemia cells. Nature. 1980;288:713–5. doi: 10.1038/288713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quadros EV, Nakayama Y, Sequeira JM. The binding properties of the human receptor for the cellular uptake of vitamin B12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:1006–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quadros EV. Advances in the understanding of cobalamin assimilation and metabolism. Br J Haematol. 148:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quadros EV, Nakayama Y, Sequeira JM. The protein and the gene encoding the receptor for the cellular uptake of transcobalamin-bound cobalamin. Blood. 2009;113:186–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall CA, Colligan PD, Begley JA. Cyclic activity of the receptors of cobalamin bound to transcobalamin II. J Cell Physiol. 1987;133:187–91. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindemans J, Kroes AC, van Geel J, van Kapel J, Schoester M, Abels J. Uptake of transcobalamin II-bound cobalamin by HL-60 cells: effects of differentiation induction. Exp Cell Res. 1989;184:449–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amagasaki T, Green R, Jacobsen DW. Expression of transcobalamin II receptors by human leukemia K562 and HL-60 cells. Blood. 1990;76:1380–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wickramasinghe SN. Morphology, biology and biochemistry of cobalamin- and folate-deficient bone marrow cells. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1995;8:441–59. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldham RK. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:582–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.9.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel AE, Houston LL, Issell BF, Fathman G. Prospects for immunotoxin therapy in cancer. Annu Rev Med. 1986;37:125–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.37.020186.001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stirpe F, Gasperi-Campani A, Barbieri L, Falasca A, Abbondanza A, Stevens WA. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from the seeds of Saponaria officinalis L. (soapwort), of Agrostemma githago L. (corn cockle) and of Asparagus officinalis L. (asparagus), and from the latex of Hura crepitans L. (sandbox tree) Biochem J. 1983;216:617–25. doi: 10.1042/bj2160617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reilly RM, Sandhu J, Alvarez-Diez TM, Gallinger S, Kirsh J, Stern H. Problems of delivery of monoclonal antibodies. Pharmaceutical and pharmacokinetic solutions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:126–42. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolognesi A, Polito L, Farini V, et al. CD38 as a target of IB4 mAb carrying saporin-S6: design of an immunotoxin for ex vivo depletion of hematological CD38+ neoplasia. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2005;19:145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polito L, Bolognesi A, Tazzari PL, et al. The conjugate Rituximab/saporin-S6 completely inhibits clonogenic growth of CD20-expressing cells and produces a synergistic toxic effect with Fludarabine. Leukemia. 2004;18:1215–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ippoliti R, Lendaro E, D'Agostino I, et al. A chimeric saporin-transferrin conjugate compared to ricin toxin: role of the carrier in intracellular transport and toxicity. Faseb J. 1995;9:1220–5. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.12.7672515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian ZM, Li H, Sun H, Ho K. Targeted drug delivery via the transferrin receptor- mediated endocytosis pathway. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:561–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniels TR, Ng PP, Delgado T, et al. Conjugation of an anti transferrin receptor IgG3-avidin fusion protein with biotinylated saporin results in significant enhancement of its cytotoxicity against malignant hematopoietic cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2995–3008. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quadros EV, Rothenberg SP, McLoughlin P. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to epitopes of human transcobalamin II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:149–54. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLean GR, Quadros EV, Rothenberg SP, Morgan AC, Schrader JW, Ziltener HJ. Antibodies to transcobalamin II block in vitro proliferation of leukemic cells. Blood. 1997;89:235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]