Abstract

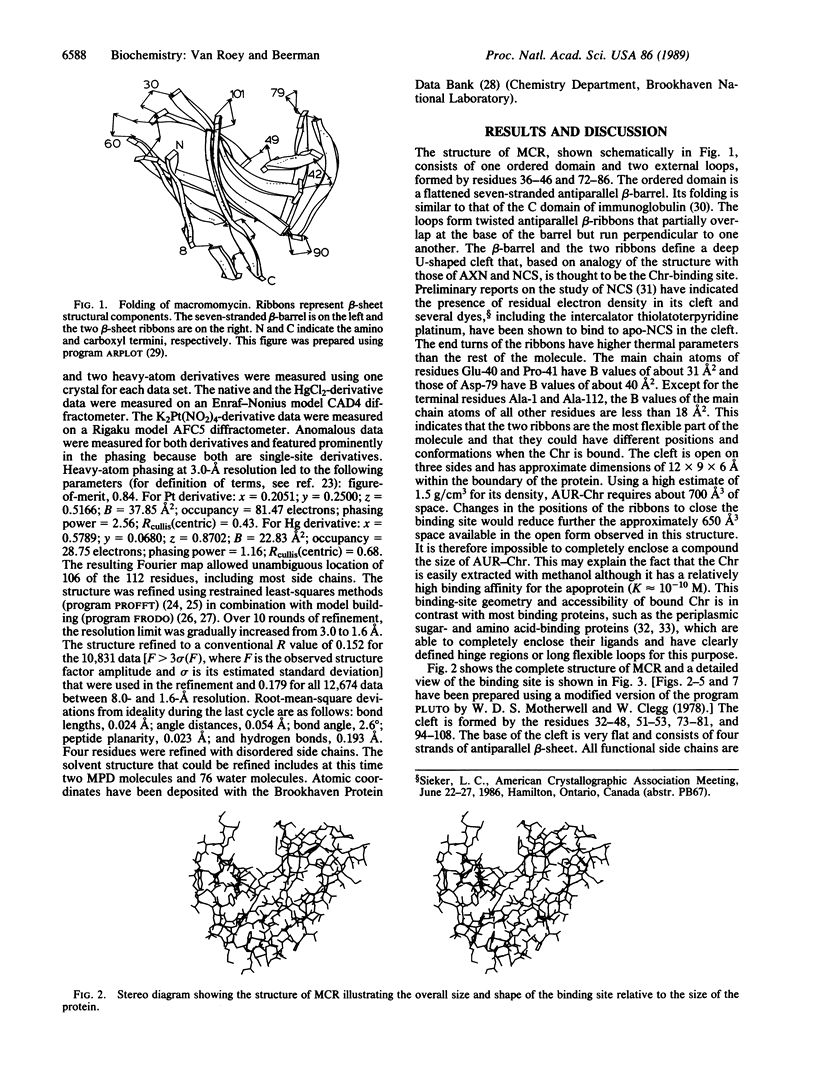

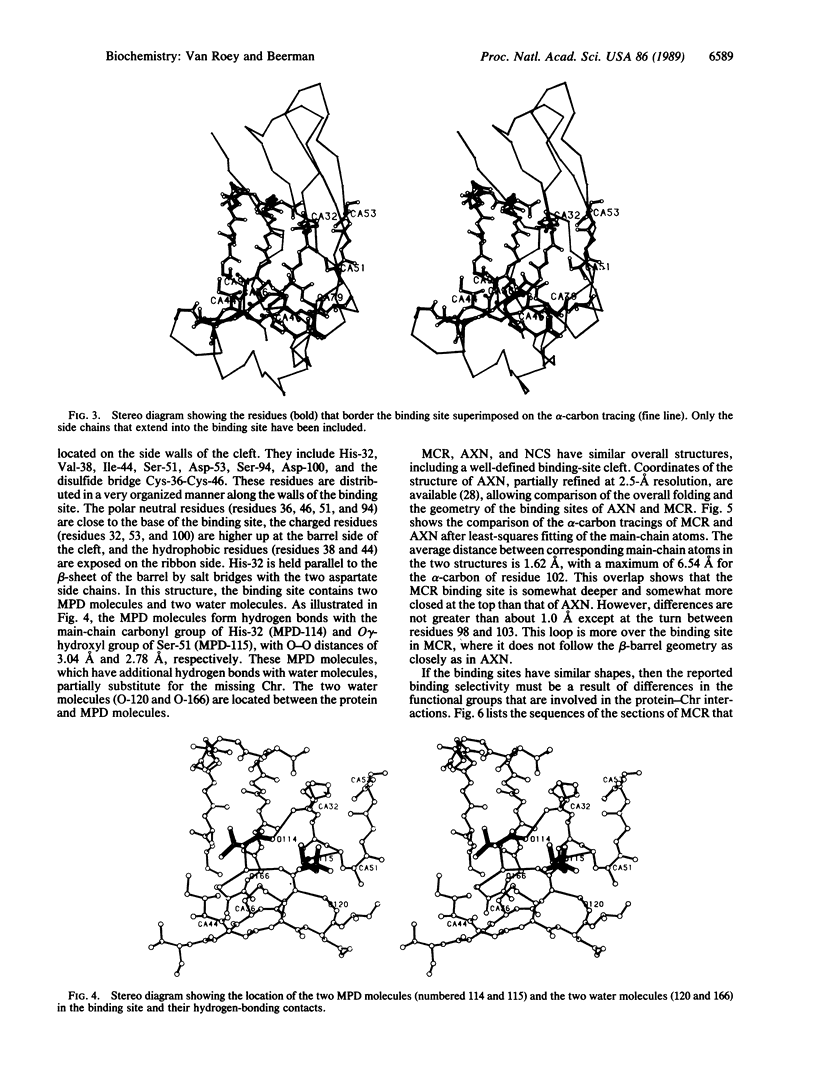

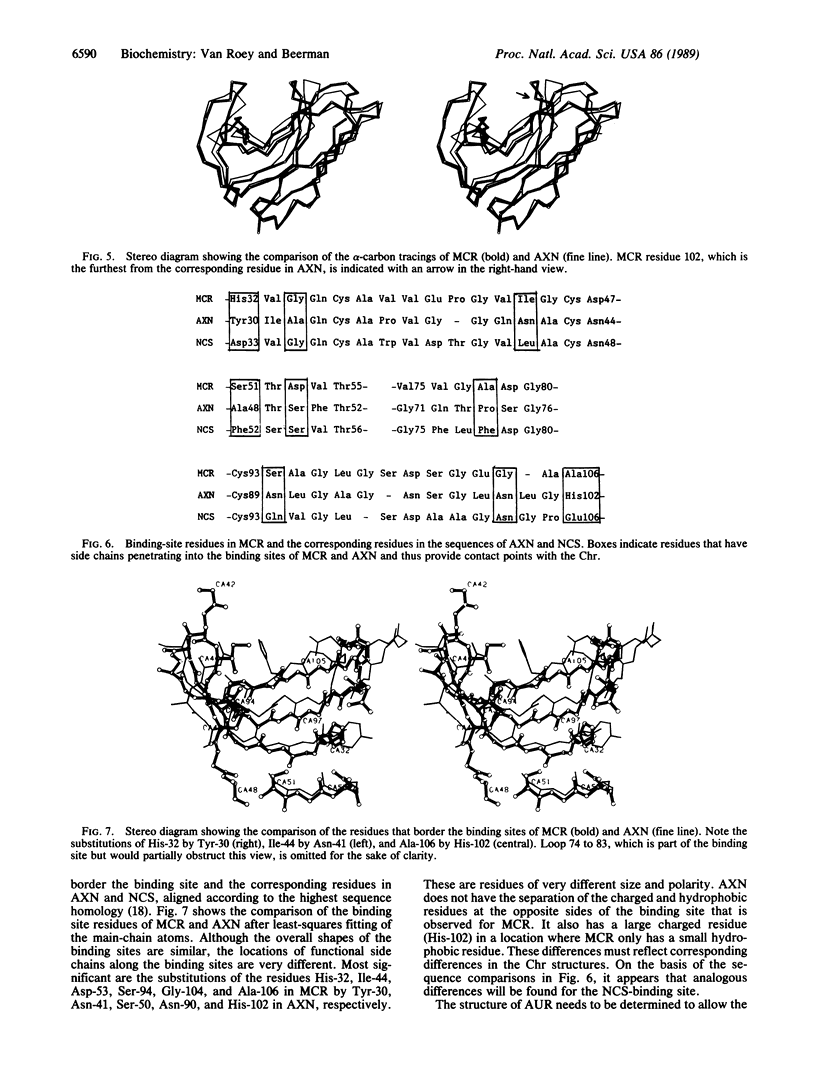

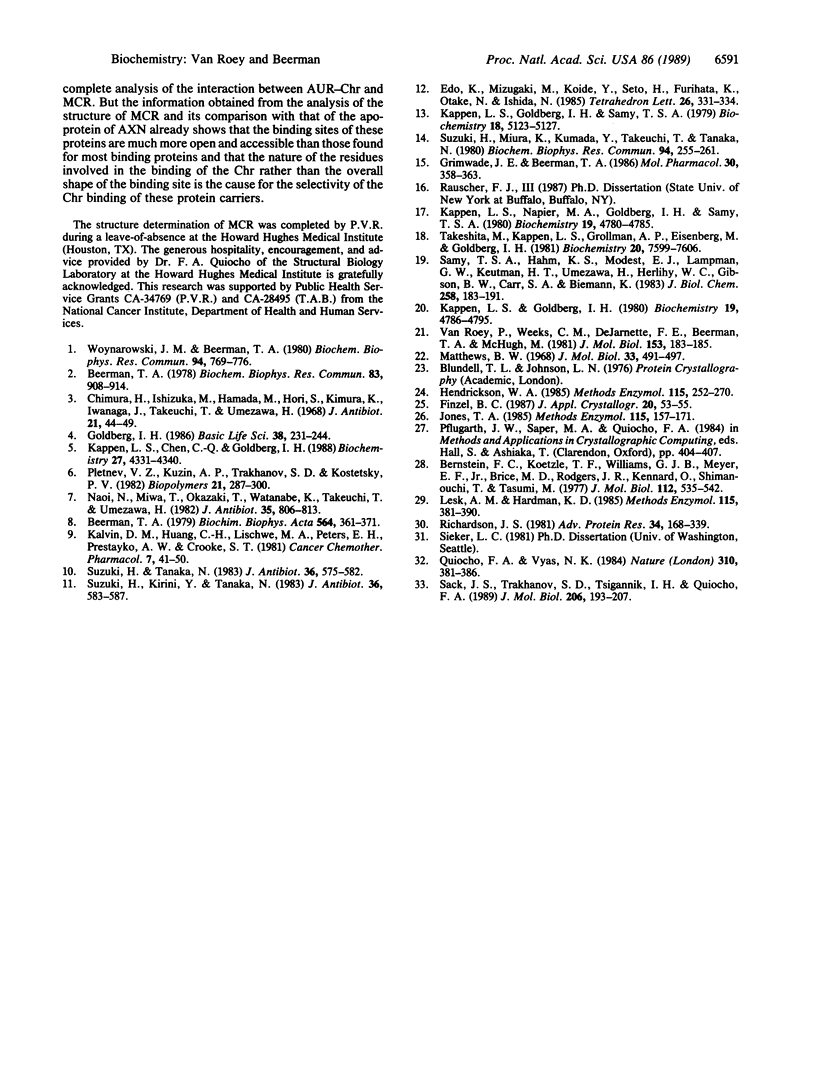

The crystal structure of macromomycin, the apoprotein of the antitumor antibiotic auromomycin, has been determined and refined at 1.6-A resolution. The overall structure is composed of a flattened seven-stranded antiparallel beta-barrel and two antiparallel beta-sheet ribbons. The barrel and the ribbons define a deep cleft that is the chromophore binding site. The cleft is very accessible and in this structure is occupied by two 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol and two water molecules. The overall shape of the binding site is similar to that of the analogue actinoxanthin. Highly specific side chains that are not conserved between different analogues extend into the binding site and may be important to the chromophore binding specificity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beerman T. A. Cellular DNA damage by the antitumor protein macromomycin and its relationship to cell growth inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Aug 14;83(3):908–914. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman T. A. Strand scission of superhelical and linear duplex DNAs by the antitumor protein macromomycin. Relationship of in vitro DNA damage to cell growth inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979 Oct 25;564(3):361–371. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein F. C., Koetzle T. F., Williams G. J., Meyer E. F., Jr, Brice M. D., Rodgers J. R., Kennard O., Shimanouchi T., Tasumi M. The Protein Data Bank: a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. J Mol Biol. 1977 May 25;112(3):535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimura H., Ishizuka M., Hamada M., Hori S., Kimura K. A new antibiotic, macromomycin, exhibiting antitumor and antimicrobial activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1968 Jan;21(1):44–49. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.21.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg I. H. Novel types of DNA-sugar damage in neocarzinostatin cytotoxicity and mutagenesis. Basic Life Sci. 1986;38:231–244. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9462-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade J. E., Beerman T. A. Measurement of bleomycin, neocarzinostatin, and auromomycin cleavage of cell-free and intracellular simian virus 40 DNA and chromatin. Mol Pharmacol. 1986 Oct;30(4):358–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson W. A. Stereochemically restrained refinement of macromolecular structures. Methods Enzymol. 1985;115:252–270. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. A. Diffraction methods for biological macromolecules. Interactive computer graphics: FRODO. Methods Enzymol. 1985;115:157–171. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvin D. M., Huang C. H., Lischwe M. A., Peters E. H., Prestayko A. W., Crooke S. T. DNA breakage activity of the methanol extract of auromomycin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1981;7(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00258212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Chen C. Q., Goldberg I. H. Atypical abasic sites generated by neocarzinostatin at sequence-specific cytidylate residues in oligodeoxynucleotides. Biochemistry. 1988 Jun 14;27(12):4331–4340. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Goldberg I. H., Samy T. S. Contrasts in the actions of protein antibiotics on deoxyribonucleic acid structure and function. Biochemistry. 1979 Nov 13;18(23):5123–5127. doi: 10.1021/bi00590a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Goldberg I. H. Stabilization of neocarzinostatin nonprotein chromophore activity by interaction with apoprotein and with HeLa cells. Biochemistry. 1980 Oct 14;19(21):4786–4790. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Napier M. A., Goldberg I. H., Samy T. S. Requirement for reducing agents in deoxyribonucleic acid strand scisson by the purified chromophore of auromomycin. Biochemistry. 1980 Oct 14;19(21):4780–4785. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesk A. M., Hardman K. D. Computer-generated pictures of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1985;115:381–390. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B. W. Solvent content of protein crystals. J Mol Biol. 1968 Apr 28;33(2):491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naoi N., Miwa T., Okazaki T., Watanabe K., Takeuchi T., Umezawa H. Studies on the reconstitution of macromomycin a d auromomycin from the chromophore and protein moieties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1982 Jul;35(7):806–813. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiocho F. A., Vyas N. K. Novel stereospecificity of the L-arabinose-binding protein. Nature. 1984 Aug 2;310(5976):381–386. doi: 10.1038/310381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. S. The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem. 1981;34:167–339. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack J. S., Trakhanov S. D., Tsigannik I. H., Quiocho F. A. Structure of the L-leucine-binding protein refined at 2.4 A resolution and comparison with the Leu/Ile/Val-binding protein structure. J Mol Biol. 1989 Mar 5;206(1):193–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samy T. S., Hahm K. S., Modest E. J., Lampman G. W., Keutmann H. T., Umezawa H., Herlihy W. C., Gibson B. W., Carr S. A., Biemann K. Primary structure of macromomycin, an antitumor antibiotic protein. J Biol Chem. 1983 Jan 10;258(1):183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Kirino Y., Tanaka N. Evidence for involvement of a free radical in DNA-cleaving reaction by macromomycin and auromomycin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983 May;36(5):583–587. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Miura K., Kumada Y., Takeuchi T., Tanaka N. Biological activities of non-protein chromophores of antitumor protein antibiotics: auromycin and neocarzinostatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980 May 14;94(1):255–261. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(80)80214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Tanaka N. Quantitative analysis of DNA-cleaving activities of macromomycin, auromomycin, and their free chromophores, and some DNA-binding characteristics. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983 May;36(5):575–582. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita M., Kappen L. S., Grollman A. P., Eisenberg M., Goldberg I. H. Strand scission of deoxyribonucleic acid by neocarzinostatin, auromomycin, and bleomycin: studies on base release and nucleotide sequence specificity. Biochemistry. 1981 Dec 22;20(26):7599–7606. doi: 10.1021/bi00529a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roey P., Weeks C. M., DeJarnette F. E., Beerman T. A., McHugh M. Preliminary crystallographic study of macromomycin. J Mol Biol. 1981 Nov 25;153(1):183–185. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woynarowski J. M., Beerman T. A. Purification and characterization of macromomycin-I, a protein antibiotic containing a non-protein chromophore. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980 Jun 16;94(3):769–776. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]