Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in the United States. New evidence reveals significant structural and metabolic changes in skeletal muscle after stroke. Muscle alterations include gross atrophy and shift to fast myosin heavy chain in the hemiparetic (contralateral) leg muscle; both are related to gait deficit severity. The underlying molecular mechanisms of this atrophy and muscle phenotype shift are not known. Inflammatory markers are also present in contralateral leg muscle after stroke. Individuals with stroke have a high prevalence of insulin resistance and diabetes. Skeletal muscle is a major site for insulin-glucose metabolism. Increasing evidence suggests that inflammatory pathway activation and oxidative injury could lead to wasting, altered function, and impaired insulin action in skeletal muscle. The health benefits of exercise in disabled populations have now been recognized. Aerobic exercise improves fitness, strength, and ambulatory performance in subjects with chronic stroke. Therapeutic exercise may modify or reverse skeletal muscle abnormalities.

Keywords: body composition, exercise, inflammation, insulin-glucose metabolism, myosin heavy chain isoforms, rehabilitation, sarcopenia, skeletal muscle, stroke, walking

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the leading cause of chronic disability in the United States, and hemiparesis is the most common chronic disabling sequela after stroke [1–3]. A paucity of literature exists on skeletal muscle abnormalities and their clinical relevance after stroke. The majority of conventional stroke rehabilitation occurs during the subacute period. Unfortunately, little rehabilitation care is prescribed during the chronic stroke phase. Few or no evidence-based recommendations promote regular exercise after stroke. Moreover, the conventional physical therapy administered during the subacute recovery period likely does not provide adequate exercise stimulus to reverse the potential skeletal muscle abnormalities or deconditioning that follow stroke [4–5]. Skeletal muscle has not been systematically pursued as a potential target for exercise and/or rehabilitation after stroke. This article outlines our current knowledge on (1) alterations of body composition and muscle structure and function in aging, inactivity, and after spinal cord injury (SCI); (2) alterations of muscle structure and function after stroke; (3) tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and inflammatory pathway activation as possible mediators of muscle atrophy and muscle injury; and (4) the beneficial effects of exercise interventions on skeletal muscle of individuals with stroke.

ALTERATIONS OF BODY COMPOSITION AND MUSCLE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION IN AGING, INACTIVITY, AND AFTER SPINAL CORD INJURY

Adaptations in Skeletal Muscle Molecular Phenotype: Skeletal Muscle Plasticity

Mammalian skeletal muscle fibers have great adaptive potential. Muscle fibers have the ability to adjust their molecular, metabolic, and functional properties in response to altered functional demands, mechanical loading, or changes in neuromuscular activity. Myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms have different structural, enzymatic, and regulatory contractile properties and can thereby impart functional diversity to muscles. Slow-twitch muscle (MHC type I) isoform fibers are rich in mitochondria, resistant to fatigue, and less pH sensitive because of their highly oxidative metabolism [6–7]. Fast-twitch fibers vary in metabolic enzymes and fiber diameter. The larger fast-twitch fibers are glycolytic fibers (MHC type IIx), and the others are glycolytic/oxidative fibers (MHC type IIa). Both fast-twitch fiber types have larger diameters and faster force-generation capacity than slow-twitch fibers (MHC type I). The slow-twitch MHC type I isoform fibers are fatigue resistant, while the fast-twitch MHC type IIx isoform fibers fatigue easily and the fast-twitch MHC type IIa isoform fibers exhibit intermediate fatigue resistance. Regulation of MHC gene expression is controlled by a complex set of processes. Muscle fiber structural and functional characteristics are not fixed; they can be modified in response to several physiological and pathological conditions. Muscle MHC phenotype is regulated by growth hormone, insulin growth factor, thyroid, changes in load, innervation patterns, age-related changes, hypoxia, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPkinase) and stress pathway activation, electrical stimulation, and exercise [8–15]. The type and proportion of MHC isoforms expressed can serve as a cellular “marker” for muscle plasticity in response to perturbations. Muscle fiber properties can also be modified by pharmacological agents such as beta2-adrenergic agonists and corticosteroids. We would like to understand the factors regulating contractile protein, MHC, and skeletal muscle adaptations in response to altered use, loading states, and neural activation patterns after stroke. This information would inform efforts to assess the effect of various rehabilitation strategies that target skeletal muscle for chronic stroke.

Muscle Changes Related to Aging, Immobility, and Spinal Cord Injury

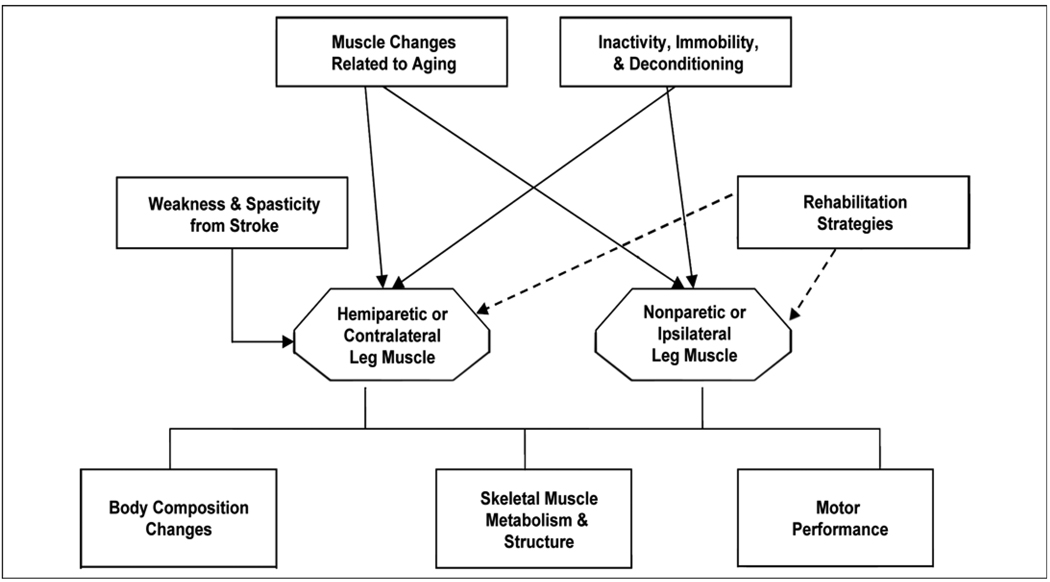

Sarcopenia of aging is a multifactorial process that affects skeletal muscle, including that of individuals with chronic stroke (Figure 1). Aging is associated with reduced strength, contraction velocity, and injury recovery [16–17]. Aging also results in decreased synthesis of myofibrillar components, increased production of catabolic cytokines, atrophy, and altered muscle metabolism [18–21]. With aging, motor unit dropout is coupled with increased motor unit size. The motor unit size increases because of reinnervation of adjacent denervated muscle fibers. Fast-twitch fibers are the most vulnerable to denervation and then reinnervation by slow-twitch motor neurons [22]. Normal aging leads to larger slow-twitch and smaller fast-twitch motor units, with an overall increase in slow-twitch fiber mass. This age-related increase in slow-twitch muscle is in opposition to our finding of increased fast-twitch MHC isoforms after stroke [23]. Aging also results in single fibers coexpressing multiple MHC isoforms [24]. Independent of age-related MHC isoform phenotype changes, calcium-activated myosin adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) activity and maximum unloaded shortening velocity are reduced and contribute to age-related slowing of muscle contraction [25]. In humans, a decline in muscle strength begins at age 40 and is more dramatic after age 65. Although muscle mass decreases by 30 to 40 percent with sarcopenia of aging, muscle force and power decrease to a much greater extent, which suggests further alterations in muscle contractile properties and metabolism [20].

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of potential influences on skeletal muscle in individuals with chronic stroke.

The disability of stroke leads to a relative inactivity, especially in the hemiparetic contralateral limb. Immobilized muscle has reduced eccentric, concentric, and isometric strength [26]. Physical inactivity results in reduced muscle mass and function, which parallel the declines that occur with aging. Muscle unloading produces a net deficit in quadriceps muscle total RNA, total messenger RNA (mRNA), and specific MHC mRNA levels, which can be partially restored with exercise [27]. Muscle immobilization reduces muscle fiber cross-sectional area [26] and downregulates MHC type I mRNA expression, while it upregulates MHC type IIx mRNA expression [26]. Physical inactivity produces similar degrees of muscle atrophy in young and old animals; however, recovery from the muscle atrophy is significantly delayed and reduced in older versus younger animals, thereby limiting recovery potential [16–17,28]. Exercise may prevent or delay sarcopenia by reducing the loss of muscle mass and strength through changes in myosin expression, even in aged mammals. However, the response to exercise is decreased in aged muscle. Because recovery from disuse atrophy is delayed with aging, minimizing the period of unweighting and immobilization is optimal. These biological processes that occur in muscle with aging and inactivity are essentially unexplored areas in stroke rehabilitation and have potentially great clinical relevance.

Skeletal muscle following stroke may be affected by the altered central neural activation and spasticity, similar to the muscle changes that occur after SCI. The weakness and spasticity have an interesting influence on the muscle, causing both reduced motor unit recruitment and excessive cocontraction, with an overactive stretch reflex. SCI induces a rapid loss of muscle mass and replacement with intramuscular fat [29]. MHC transcriptional activity is reduced and a shift to a fast-twitch MHC isoform profile occurs, especially an increase in MHC type IIx isoforms [30–31]. Skeletal muscle sodium-potassium ATPase concentration is reduced in spastic muscle [32]. The increased shortening velocity and fatigability of the paralyzed quadriceps muscles after SCI and other conditions that result in spasticity are probably secondary to the shift to fast-twitch MHC isoforms, reduced sodium-potassium ATPase concentration, reduced capillary density, and reduced oxidative capacity [32–36]. In addition, gene expression of enzymes that affect protein degradation (calpain-1 and enzymes associated with polyubquitination) is increased [30], which could contribute to muscle wasting after SCI. These findings suggest that muscle atrophy after SCI is likely a multifactorial process that affects transcription, translation, and protein degradation.

ALTERATIONS OF MUSCLE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION AFTER STROKE

Muscular Atrophy and Phenotype Shift After Stroke: Relation to Fitness and Function

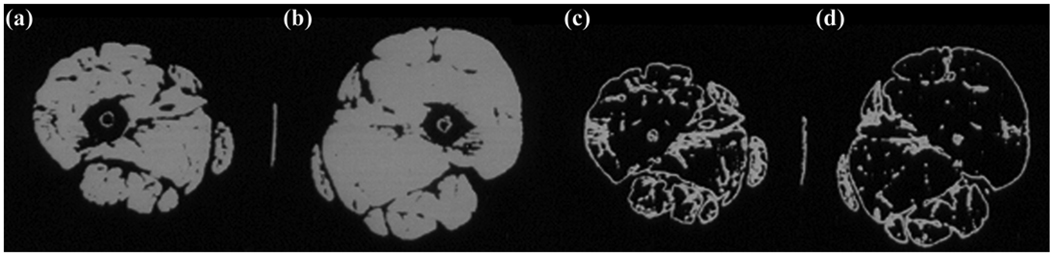

Traditionally, upper motor neuron injury, as occurs in stroke, is not believed to result in muscular atrophy. Few studies have examined muscle abnormalities after stroke and their relationship to fitness and function. We examined relationships between gait deficit severity, peak oxygen consumption (VO2), and body composition using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in 60 chronic hemiparetic stroke patients and found that lean mass of the contralateral limb was lower than that of the ipsilateral limb (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] = 8.3 ± 1.6 kg vs 8.6 ± 1.7 kg, p < 0.001) [37]. Stepwise regression revealed that both contralateral thigh lean mass (r = 0.61) and walking speed (cumulative r = 0.79) were independent and robust predictors of reduced fitness (VO2) and accounted for 62 percent of the observed variance (p < 0.01). In contrast, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, the modified Ashworth spasticity scale, stroke onset latency, and percent body fat were unrelated to VO2. These DXA results are substantiated by bilateral midthigh computed tomography cross-sectional area measurements in 30 chronic stroke patients. The contralateral midthigh area (mean ± SEM = 86.1 ± 29.3 cm2) had 20 percent lower muscle cross-sectional area (p < 0.001) than the ipsilateral midthigh area (mean ± SEM = 100.9 ± 27.9 cm2) (Figure 2) [38]. The reduced thigh muscle mass predicted lower VO2 in these patients [37]. The contralateral thigh muscle also had 25 percent higher intramuscular area fat deposition (p < 0.001) (Figure 2), a finding strongly associated with insulin resistance and its complications [38–40]. The reduced muscle mass and increased intramuscular fat are similar to recent findings in individuals with incomplete SCI [29]. Although these results suggest that reduced muscle mass is fundamentally related to poor fitness and physical performance capacity after stroke, they do not establish causality and do not account for reduced central muscle activation.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (CT) images show atrophy of (a) paretic leg midthigh muscle area compared with (b) nonparetic thigh. Low-density CT lean-tissue imaging of same individual shows increased intramuscular fat content in (c) paretic compared with (d) nonparetic thigh after stroke.

Altered Muscle Phenotype in Stroke

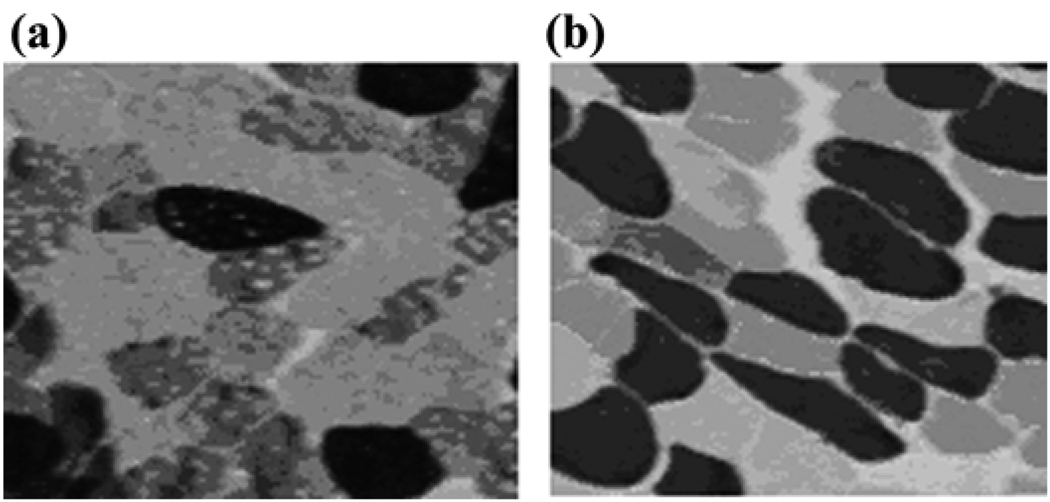

Little is known about skeletal muscle phenotypic abnormalities after stroke. Mechanisms for skeletal muscle alterations are probably similar in stroke and incomplete SCI, with reduced neuromuscular activation and muscle unloading but retained neuromuscular connectivity. Basic pathological studies reveal variable results with altered fiber type proportions, including selective fast-twitch MHC fiber atrophy and specific loss of slow-twitch MHC fibers in hemiparetic limbs of stroke patients [36,41–44]. The most comprehensive study by Landin et al. revealed (1) a shift to greater fast-twitch fiber proportions in the contralateral leg vastus lateralis (VL) muscle based on ATPase staining and (2) a reliance on anaerobic metabolism with rapid lactate generation during isolated contralateral or hemiparetic limb exercise in contrast to the oxidative metabolism during isolated ipsilateral leg exercise [44]. These findings are concordant with the major shift to fast-twitch MHC that we found in our recent study using routine ATPase staining at pH 4.6 and MHC immunohistochemistry and gel electrophoresis of bilateral leg VL muscle biopsies (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Bilateral VL biopsies from 13 untrained stroke patients showed a significantly elevated proportion of fast-twitch MHC isoforms in the contralateral (mean ± SEM = 68% ± 14%, range 46%–88% of total MHC) versus ipsilateral leg (mean ± SEM = 50% ± 13%, range 32%–76%, p < 0.005) [23]. Interestingly, this shift to fast-twitch MHC composition in the contralateral muscle parallels that seen in animals and humans after SCI [45–46]. This result suggests that neurological alterations may be partially responsible for the muscle phenotype shift. The shift to fast-twitch MHC is in contrast to the shift to slow-twitch MHC in aging, where fast-twitch fibers are lost through denervation and slow-twitch fiber density increases through reinnervation [22]. The shift to fast-twitch MHC after stroke in contralateral leg muscle would be expected to result in a more fatigable muscle fiber type that could be more insulin resistant. In the contralateral leg only, the proportion of fast-twitch MHC isoform is strongly and negatively correlated to self-selected walking speed (r = –0.78, p < 0.005), which suggests that neurological gait deficit severity may be a major contributor to MHC isoform expression and account for as much as 61 percent of its variance. The findings suggest that shifts in muscle phenotype may be fundamentally related to neuromuscular function. In our cohort, the muscular atrophy and the shift to the fast-twitch MHC isoform in the contralateral leg were both strong predictors of gait deficit severity [23,37]. Unfortunately, the current studies cannot explain the direction of these relationships; i.e., whether the atrophy and the shift in MHC expression are caused by or are a result of the gait deficit.

Figure 3.

Muscle tissue cross-sectional samples from (a) paretic and (b) nonparetic vastus lateralis (VL) muscle after stroke were stained with adenosine triphosphatase at pH 4.6. In paretic muscle, clear lack of slow-twitch myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoform (type I [dark]) fibers and relative atrophy of fast-twitch MHC isoform (type IIa [light] and type IIx [medium]) fibers were present compared with normal mosaic equal distribution of slow- and fast-twitch MHC isoform fibers in nonparetic VL muscle.

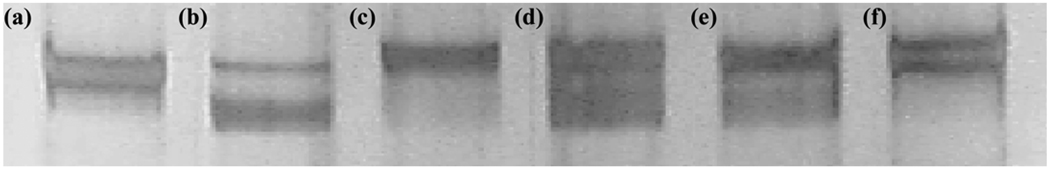

Figure 4.

Silver-stained gel electrophoresis for slow- and fast-twitch myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms in paretic and nonparetic vastus lateralis muscles. (a) Rat extensor digitorum longus (predominantly fast-twitch MHC: upper band), (b) rat soleus (predominantly slow-twitch MHC: lower band), (c) and (f) hemiparetic limb of subject with stroke (absent slow-twitch MHC), and (d) and (e) nonparetic limb of subject with stroke (equal proportions of slow- and fast-twitch MHC).

TNF-α AND INFLAMMATORY PATHWAY ACTIVATION AS POSSIBLE MEDIATORS OF MUSCLE ATROPHY AND ALTERED MUSCLE METABOLISM AFTER STROKE

TNF-α and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) have been implicated with muscular atrophy in models of disuse, cachexia, and sarcopenia. TNF-α may contribute to atrophy through a number of mechanisms, including inhibition of protein synthesis and reduced expression of MyoD, a transcriptional regulator of myofiber gene expression and accelerated protein breakdown through activation of ubiquitin proteases and NF-κB and apoptotic cell death [47–52]. TNF-α appears to preferentially downregulate adult slow-twitch MHC protein synthesis and enhance its degradation [53], which may in part explain our findings of elevated fast-twitch MHC in the hemiparetic leg. TNF-α also activates NF-κB transcriptional factor [54], which may increase inducible nitric oxide [55–56] with subsequent formation of reactive oxygen species [57] and oxidative injury [58–62]. In vitro studies show that oxidative stress activates p38 MAPkinase signaling pathways, which regulate gene expression that could potentially influence muscle structure and function [63]. The presence of reactive oxidative species disturbs muscle redox status and can result in muscle fatigue and/or injury and further activates NF-κB [62]. Cytokine-independent activation of NF-κB is also associated with muscle atrophy [64]. These inflammatory mediators can negatively affect muscle mass, structural proteins, and performance.

Although TNF-α is negligibly expressed in skeletal muscle, we found that TNF-α mRNA expression is elevated in the contralateral VL muscle of patients with stroke compared with the ipsilateral leg of patients with stroke and age-matched nonneurological control subjects [65]. TNF-α mRNA levels were three times higher in contralateral leg muscle of patients with stroke than in control muscles. A trend existed for almost two times higher TNF-α in the ipsilateral leg muscle compared with nondisabled control subjects. The finding of elevated TNF-α in both the contralateral and ipsilateral leg muscles suggests a systemic as well as local inflammation that could augment hemiparetic leg muscular atrophy and increase insulin resistance after stroke. Three-quarters of these subjects with stroke and elevated skeletal muscle TNF-α were on anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin, or hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase medications and insulin sensitizers, which suggests that these medications are not capable of completely countering inflammation at the level of the skeletal muscle. We also found, using a complementary DNA NF-κB signaling gene miniarray (GE SuperArray, General Electric, Co; Fairfield, Connecticut), that NF-κB inflammatory pathway gene activation is differentially upregulated in the contralateral compared with the ipsilateral VL muscle (N = 6).* Products of NF-κB activation could mediate atrophy, accelerate oxidative injury, and alter important structural proteins. Elevated TNF-α protein and mRNA in frail elderly skeletal muscles can be decreased with strength training [66]. Thus, interventions aimed at attenuating elevated skeletal muscle inflammatory pathways may represent new targets for reducing both disability and cardiovascular disease risk after stroke.

A remarkably large incidence of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes is present in individuals who had stroke [67–68]. New evidence from the Dutch Transient Ischemic Attack Trial reveals a two- and threefold increased risk of stroke for individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes, respectively [68]. Circulating levels of TNF-α and interleukin-6 are elevated in subjects with type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance [69–70]. Systemic and muscle-specific elevations in TNF-α are strongly linked to insulin resistance and diabetes [71]. TNF-α directly impairs insulin signaling in muscle [72] and is inversely related to maximum glucose disposal rate [71–74]. Exercise can reduce TNF-α and improve skeletal muscle metabolism and systemic insulin sensitivity [75]. Hence, better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of accelerated inflammation in the contralateral leg muscle of subjects with stroke and effects of exercise may have important implications for cardiovascular health of people who remain at high risk for stroke recurrence.

BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF EXERCISE INTERVENTIONS ON SKELETAL MUSCLE IN CHRONIC STROKE

A number of aerobic and resistive exercise training strategies have proven beneficial for patients with chronic stroke. These exercise strategies include treadmill, robot-assisted walking, and strength training [76– 80]. Exercise may have many beneficial effects at the level of skeletal muscle after stroke. It may prevent changes associated with physical inactivity. Exercise in nonneurological populations and animal models can prevent or delay sarcopenia through changes in myosin expression and reduce loss of muscle mass and strength [37,81]. Elevated TNF-α protein and mRNA in frail elderly skeletal muscles can be decreased with strength training [66]. Aerobic exercise can produce skeletal muscle adaptations that protect myocytes and muscle fibers from muscle injury, improve muscle performance, and delay muscle fatigue [27,81–84]. To our knowledge, the effects of exercise on muscle structure and function have never been systematically studied after stroke.

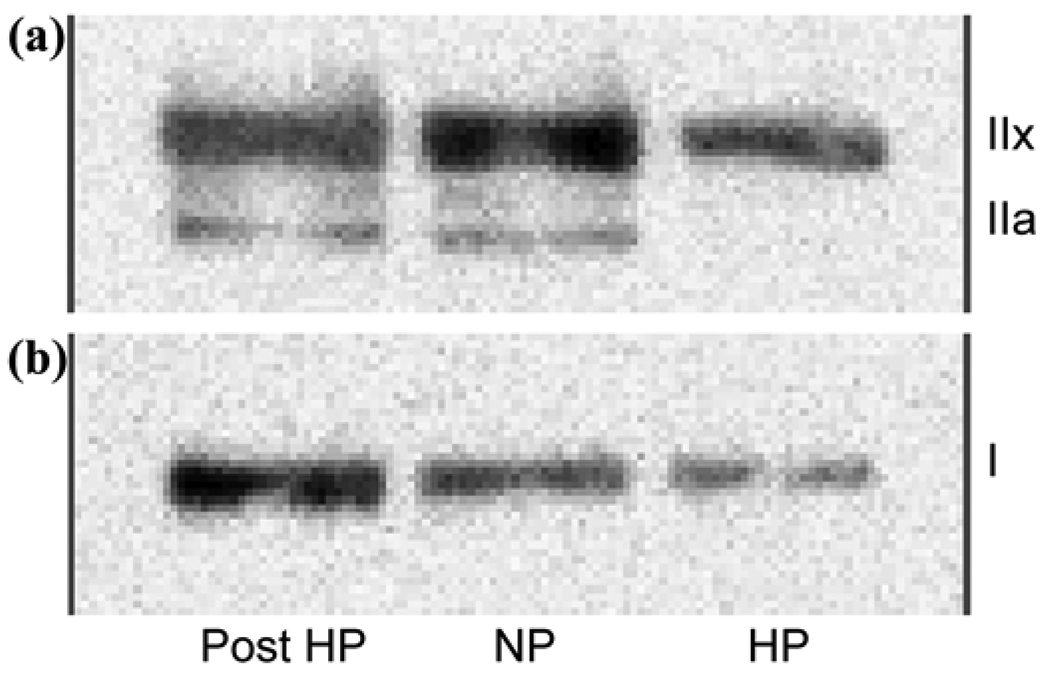

We and others have reported that treadmill aerobic exercise, as a task-oriented training model, improves fitness and mobility function in patients with chronic stroke [76,85–90]. Our results show that treadmill exercise is superior to a program with components of “conventional rehabilitation therapy” for improving fitness and mobility function levels in patients with chronic stroke [85–90]. Aerobic exercise can induce profound molecular changes in “neurologically intact” muscle [91], promoting fast- to slow-twitch MHC fiber conversion. Treadmill exercise had a significant effect on MHC expression. The total MHC concentration and proportion of slow- and fast-twitch MHC type IIa isoforms in the contralateral limb significantly increase after 6 months of treadmill exercise (Figure 5).* In contrast, the control stroke group that was enrolled in a 6-month time-matched stretching program did not have a significant change in the MHC concentration or profile distribution. In a small cohort of patients with chronic stroke, these data suggest that treadmill exercise can reverse the contralateral leg MHC profile abnormalities. The beneficial effects of aerobic exercise training have also been demonstrated in SCI [83,92–93]. Functional electric stimulation can induce skeletal muscle changes, such as a shift to a fast-twitch MHC phenotype in SCI [94–95]. Transcranial electrical nerve stimulation can improve H reflex response and reduce spasticity after stroke and, in combination with task-related training, improve walking function [46,96]. Finally, pharmaceutical agents can also target skeletal muscle. Beta2-adrenergic agonists can induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy by inducing myocyte proliferation, myogenic differentiation, satellite cell recruitment into muscle fibers, and the initiation of translation that increases protein synthesis [97–98]. As our understanding of the ability of exercise rehabilitation strategies to improve skeletal muscle structure and function increases, we will be better poised to prescribe specific rehabilitation protocols that reduce the musculoskeletal component of disability after stroke.

Figure 5.

Western Blot analysis of (a) fast- and (b) slow-twitch myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms shows significant reduction in total MHC in hemiparetic (HP) vastus lateralis muscle, with reduced level of fast-twitch MHC type IIx and slow-twitch MHC and no MHC type IIa isoform fibers compared with nonparetic leg (NP). After 6 months of treadmill aerobic exercise training (Post), significant increases in total MHC and proportions of slow-twitch MHC type I and fast-twitch oxidative MHC type IIa fibers with relative reduction in proportion of MHC type IIx fibers in paretic leg (Post HP) were noted.

SUMMARY

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in the United States. This disability is traditionally attributed to the brain injury and the high risk for recurrent stroke ascribed to preexisting cardiovascular disease risk factors. We propose a new hypothesis that secondary biological abnormalities of muscle atrophy, altered contractile protein expression, and inflammation in the contralateral leg skeletal muscle propagate disability. While animal models and clinical data show that both disuse and abnormal neural innervation can produce such abnormalities, little is known about their presence after stroke and their potential for reversal with exercise. We report altered major structural skeletal muscle proteins and activation of inflammatory pathways in bilateral VL muscle biopsies from untrained hemiparetic stroke patients. Contralateral leg muscle biopsies obtained after the 6-month treadmill exercise program can help us determine the training components of the aerobic treadmill exercise program that produce the greatest beneficial adaptations in skeletal muscle. Study results may provide a biological rationale and new molecular targets for novel pharmacological therapeutics aimed at improving muscle structure and metabolic function after stroke. The biological relevance and potential for clinical applications in both disability reduction and secondary cardiovascular disease prevention will likely extend to other neurological conditions that engender disuse and abnormal neural innervation, such as multiple sclerosis, closed head injury, and SCI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material was based on work supported in part by the Baltimore Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center; the Baltimore VA Maryland Exercise and Robotics Center of Excellence (R. F. Macko); the Baltimore VA Research Enhancement Award Program (R. F. Macko); VA Merit Awards (C. E. Hafer-Macko and A. S. Ryan); a VA Research Career Scientist Award (A. S. Ryan); the University of Maryland Claude D. Pepper Center (grant P30-AG-12583, A. P. Goldberg); and National Institutes of Health (grant R01-AG-019310, A. S. Ryan).

Abbreviations

- ATPase

adenosine triphosphatase

- DXA

dual X-ray absorptiometry

- MAPkinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MHC

myosin heavy chain

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VA

Department of Veterans Affairs

- VL

vastus lateralis

- VO2

peak oxygen consumption

Footnotes

Hafer-Macko CE, Unpublished observations, 2008.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart and stroke facts. Dallas (TX): American Heart Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post-Stroke Rehabilitation Guideline Panel, U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Post-stroke rehabilitation: Clinical practice guideline. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gresham GE, Phillips TF, Wolfe PA, McNamara PM, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. Epidemiologic profile of long-term stroke disability: The Framingham study. 1979;60(11):487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, Szidon JP, Fogg L, Tincknell T. Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. 1995;26(1):101–105. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKay-Lyons MJ, Makrides L. Cardiovascular stress during a contemporary stroke rehabilitation program: Is the intensity adequate to induce a training effect? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(10):1378–1383. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.35089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson SK. Ca2+-activated force-generating properties of mammalian skeletal muscle fibres: Histochemically identified single peeled rabbit fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1984;5(6):593–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00713922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottinelli R. Functional heterogeneity of mammalian single muscle fibres: Do myosin isoforms tell the whole story? Pflugers Arch. 2001;443(1):6–17. doi: 10.1007/s004240100700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange KH, Andersen JL, Beyer N, Isaksson F, Larsson B, Rasmussen MH, Juul A, Bülow J, Kjær M. GH administration changes myosin heavy chain isoforms in skeletal muscle but does not augment muscle strength or hypertrophy, either alone or combined with resistance exercise training in healthy elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):513–523. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Alnaqeeb M, Simpson H, Goldspink G. Changes in muscle fibre type, muscle mass and IGF-I gene expression in rabbit skeletal muscle subjected to stretch. J Anat. 1997;190(Pt 4):613–622. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19040613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buller AJ, Proske U. Further observations on back-firing in the motor nerve fibres of a muscle during twitch contractions. J Physiol. 1978;285:59–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higginson J, Wackerhage H, Woods N, Schjerling P, Ratkevicius A, Grunnet N, Quistorff B. Blockades of mitogen-activated protein kinase and calcineurin both change fibre-type markers in skeletal muscle culture. Pflugers Arch. 2002;445(3):437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0939-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pette D, Vrbová G. Adaptation of mammalian skeletal muscle fibers to chronic electrical stimulation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;120:115–202. doi: 10.1007/BFb0036123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochester L, Barron MJ, Chandler CS, Sutton RA, Miller S, Johnson MA. Influence of electrical stimulation of the tibialis anterior muscle in paraplegic subjects. 2. Morphological and histochemical properties. Paraplegia. 1995;33(9):514–522. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pette DJB. Wolffe memorial lecture. Activity-induced fast to slow transitions in mammalian muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16(6):517–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldspink G, Scutt A, Loughna PT, Wells DJ, Jaenicke T, Gerlach GF. Gene expression in skeletal muscle in response to stretch and force generation. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(3 Pt 2):R356–R363. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.3.R356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson LV. Skeletal muscle adaptations with age, inactivity, and therapeutic exercise. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(2):44–57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2002.32.2.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degens H, Alway SE. Skeletal muscle function and hypertrophy are diminished in old age. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27(3):339–347. doi: 10.1002/mus.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE., Jr The effects of aging and training on skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):598–602. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260042401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bemben MG. Age-related alterations in muscular endurance. Sports Med. 1998;25(4):259–269. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199825040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faulkner JA, Brooks SV, Zerba E. Skeletal muscle weakness and fatigue in old age: Underlying mechanisms. Ann Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 1990;10:147–166. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-38445-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shephard RJ. Age and physical work capacity. Exp Aging Res. 1999;25(4):331–343. doi: 10.1080/036107399243788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadhiresan VA, Hassett CA, Faulkner JA. Properties of single motor units in medial gastrocnemius muscles of adult and old rats. J Physiol. 1996;493(Pt 2):543–552. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Deyne PG, Hafer-Macko CE, Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Macko RF. Muscle molecular phenotype after stroke is associated with gait speed. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(2):209–215. doi: 10.1002/mus.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Antona G, Pellegrino MA, Adami R, Rossi R, Carlizzi CN, Canepari M, Saltin B, Bottinelli R. The effect of ageing and immobilization on structure and function of human skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2003;552(Pt 2):499–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe DA, Husom AD, Ferrington DA, Thompson LV. Myofibrillar myosin ATPase activity in hindlimb muscles from young and aged rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(9):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hortobágyi T, Dempsey L, Fraser D, Zheng D, Hamilton G, Lambert J, Dohm L. Changes in muscle strength, muscle fibre size and myofibrillar gene expression after immobilization and retraining in humans. J Physiol. 2000;(524 Pt 1):293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haddad F, Baldwin KM, Tesch PA. Pretranslational markers of contractile protein expression in human skeletal muscle: Effect of limb unloading plus resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(1):46–52. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00553.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka T, Kariya Y, Hoshino Y. Histochemical study on the changes in muscle fibers in relation to the effects of aging on recovery from muscular atrophy caused by disuse in rats. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9(1):76–85. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0734-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorgey AS, Dudley GA. Skeletal muscle atrophy and increased intramuscular fat after incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(4):304–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haddad F, Roy RR, Zhong H, Edgerton VR, Baldwin KM. Atrophy responses to muscle inactivity. II. Molecular markers of protein deficits. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(2):791–802. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01113.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutchinson KJ, Linderman JK, Basso DM. Skeletal muscle adaptations following spinal cord contusion injury in rat and the relationship to locomotor function: A time course study. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18(10):1075–1089. doi: 10.1089/08977150152693764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ditor DS, Hamilton S, Tarnopolsky MA, Green HJ, Craven BC, Parise G, Hicks AL. Na+,K+-ATPase concentration and fiber type distribution after spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(1):38–45. doi: 10.1002/mus.10534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pontén EM, Stål PS. Decreased capillarization and a shift to fast myosin heavy chain IIx in the biceps brachii muscle from young adults with spastic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2007;253(1–2):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talmadge RJ, Roy RR, Caiozzo VJ, Edgerton VR. Mechanical properties of rat soleus after long-term spinal cord transection. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(4):1487–1497. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00053.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerrits HL, Hopman MT, Offringa C, Engelen BG, Sargeant AJ, Jones DA, Haan A. Variability in fibre properties in paralysed human quadriceps muscles and effects of training. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445(6):734–740. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jakobsson F, Edström L, Grimby L, Thornell LE. Disuse of anterior tibial muscle during locomotion and increased proportion of type II fibres in hemiplegia. J Neurol Sci. 1991;105(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90117-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan AS, Dobrovolny CL, Silver KH, Smith GV, Macko RF. Cardiovascular fitness after stroke: Role of muscle mass and gait deficit severity. J Stroke Cerebro Dis. 2000;9:185–191. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2000.7237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan AS, Dobrovolny CL, Smith GV, Silver KH, Macko RF. Hemiparetic muscle atrophy and increased intramuscular fat in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(12):1703–1707. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan AS, Nicklas BJ. Age-related changes in fat deposition in mid-thigh muscle in women: Relationships with metabolic cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(2):126–132. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Diabetes. 1997;46(10):1579–1585. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chokroverty S, Reyes MG, Rubino FA, Barron KD. Hemiplegic amyotrophy. Muscle and motor point biopsy study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33(2):104–110. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500020032006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frontera WR, Grimby L, Larsson L. Firing rate of the lower motoneuron and contractile properties of its muscle fibers after upper motoneuron lesion in man. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20(8):938–947. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199708)20:8<938::aid-mus2>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hachisuka K, Umezu Y, Ogata H. Disuse muscle atrophy of lower limbs in hemiplegic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landin S, Hagenfeldt L, Saltin B, Wahren J. Muscle metabolism during exercise in hemiparetic patients. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53(3):257–269. doi: 10.1042/cs0530257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huey KA, Haddad F, Qin AX, Baldwin KM. Transcriptional regulation of the type I myosin heavy chain gene in denervated rat soleus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284(3):C738–C748. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00389.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shields RK, Dudley-Javoroski S. Musculoskeletal plasticity after acute spinal cord injury: Effects of long-term neuromuscular electrical stimulation training. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95(4):2380–2390. doi: 10.1152/jn.01181.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frost RA, Lang CH, Gelato MC. Transient exposure of human myoblasts to tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits serum and insulin-like growth factor-I stimulated protein synthesis. Endocrinology. 1997;138(10):4153–4159. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Madrid LV, Wang CY, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB-induced loss of MyoD messenger RNA: Possible role in muscle decay and cachexia. Science. 2000;289(5488):2363–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman MN. Tumor necrosis factor induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(5 Pt 1):E727–E730. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.5.E727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheema IR, Hermann C, Postell S, Barnes P. Effect of chronic excess of tumour necrosis factor-alpha on contractile proteins in rat skeletal muscle. Cytobios. 2000;103(404):169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Llovera M, García-Martínez C, Agell N, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. TNF can directly induce the expression of ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system in rat soleus muscles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230(2):238–241. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vescovo G, Zennaro R, Sandri M, Carraro U, Leprotti C, Ceconi C, Ambrosio GB, Dalla Libera L. Apoptosis of skeletal muscle myofibers and interstitial cells in experimental heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30(11):2449–2459. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips T, Leeuwenburgh C. Muscle fiber specific apoptosis and TNF-alpha signaling in sarcopenia are attenuated by life-long calorie restriction. FASEB J. 2005;19(6):668–670. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2870fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li YP, Schwartz RJ, Waddell ID, Holloway BR, Reid MB. Skeletal muscle myocytes undergo protein loss and reactive oxygen-mediated NF-kappaB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha. FASEB J. 1998;12(10):871–880. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.10.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li YP, Reid MB. NF-kappaB mediates the protein loss induced by TNF-alpha in differentiated skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279(4):R1165–R1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams V, Späte U, Kränkel N, Schulze PC, Linke A, Schuler G, Hambrecht R. Nuclear factor-kappa B activation in skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure: Correlation with the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10(4):273–277. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams V, Nehrhoff B, Späte U, Linke A, Schulze PC, Baur A, Gielen S, Hambrecht R, Schuler G. Induction of iNOS expression in skeletal muscle by IL-1beta and NFkappaB activation: An in vitro and in vivo study. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fries DM, Paxinou E, Themistocleous M, Swanberg E, Griendling KK, Salvemini D, Slot JW, Heijnen HF, Hazen SL, Ischiropoulos H. Expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase and intracellular protein tyrosine nitration in vascular smooth muscle cells: Role of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(25):22901–22907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reid MB, Li YP. Tumor necrosis factor and muscle wasting: A cellular perspective. Respir Res. 2001;2(5):269–272. doi: 10.1186/rr67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan ZQ, Sirsjö A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G, Hansson GK. Augmented expression of inducible NO synthase in vascular smooth muscle cells during aging is associated with enhanced NF-kappaB activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(12):2854–2862. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goto S, Nakamura A, Radak Z, Nakamoto H, Takahashi R, Yasuda K, Sakurai Y, Ishii N. Carbonylated proteins in aging and exercise: Immunoblot approaches. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;107(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marshall HE, Merchant K, Stamler JS. Nitrosation and oxidation in the regulation of gene expression. FASEB J. 2000;14(13):1889–1900. doi: 10.1096/fj.00.011rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zarzhevsky N, Menashe O, Carmeli E, Stein H, Reznick AZ. Capacity for recovery and possible mechanisms in immobilization atrophy of young and old animals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;928:212–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li YP, Atkins CM, Sweatt JD, Reid MB. Mitochondria mediate tumor necrosis factor-alpha/NF-kappaB signaling in skeletal muscle myotubes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 1999;1(1):97–104. doi: 10.1089/ars.1999.1.1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hafer-Macko CE, Yu S, Ryan AS, Ivey FM, Macko RF. Elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skeletal muscle after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36(9):2021–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177878.33559.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greiwe JS, Cheng B, Rubin DC, Yarasheski KE, Semenkovich CF. Resistance exercise decreases skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor alpha in frail elderly humans. FASEB J. 2001;15(2):475–482. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0274com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Bravata M, Shulman GI, McVeety JC, Horwitz RI. Impaired insulin sensitivity among nondiabetic patients with a recent TIA or ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1447–1451. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063318.66140.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Garrity BM, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. High prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism and poor sensitivity of fasting plasma glucose in the chronic phase of stroke. Cere-brovasc Dis. 2006;22(5–6):368–371. doi: 10.1159/000094853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mishima Y, Kuyama A, Tada A, Takahashi K, Ishioka T, Kibata M. Relationship between serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha and insulin resistance in obese men with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;52(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Garvey WT, Henry RR, Kern PA. The expression of TNF alpha by human muscle. Relationship to insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(4):1111–1116. doi: 10.1172/JCI118504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Plomgaard P, Bouzakri K, Krogh-Madsen R, Mittendorfer B, Zierath JR, Pedersen BK. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces skeletal muscle insulin resistance in healthy human subjects via inhibition of Akt substrate 160 phosphorylation. Diabetes. 2005;54(10):2939–2945. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamaguchi K, Higashiura K, Ura N, Murakami H, Hyakukoku M, Furuhashi M, Shimamoto K. The effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on tissue specificity and selectivity to insulin signaling. Hypertens Res. 2003;26(5):389–396. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Alvaro C, Teruel T, Hernandez R, Lorenzo M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha produces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by activation of inhibitor kB kinase in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17070–17078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henriksen EJ. Invited review: Effects of acute exercise and exercise training on insulin resistance. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(2):788–796. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01219.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, Szidon JP, Fogg L, Tincknell T. Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. 1995;26(1):101–105. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mayr A, Kofler M, Quirbach E, Matzak H, Fröhlich K, Saltuari L. Prospective, blinded, randomized crossover study of gait rehabilitation in stroke patients using the Lokomat gait orthosis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007;21(4):307–314. doi: 10.1177/1545968307300697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang YR, Wang RY, Lin KH, Chu MY, Chan RC. Task-oriented progressive resistance strength training improves muscle strength and functional performance in individuals with stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(10):860–870. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Teixeira-Salmela LF, Olney SJ, Nadeau S, Brouwer B. Muscle strengthening and physical conditioning to reduce impairment and disability in chronic stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(10):1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ouellette MM, LeBrasseur NK, Bean JF, Phillips E, Stein J, Frontera WR, Fielding RA. High-intensity resistance training improves muscle strength, self-reported function, and disability in long-term stroke survivors. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1404–1409. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127785.73065.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gür H, Gransberg L, VanDyke D, Knutsson E, Larsson L. Relationship between in vivo muscle force at different speeds of isokinetic movements and myosin isoform expression in men and women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;88(6):487–496. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crameri RM, Langberg H, Magnusson P, Jensen CH, Schrøder HD, Olesen JL, Suetta C, Teisner B, Kjaer M. Changes in satellite cells in human skeletal muscle after a single bout of high intensity exercise. J Physiol. 2004;558(Pt 1):333–340. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stewart BG, Tarnopolsky MA, Hicks AL, McCartney N, Mahoney DJ, Staron RS, Phillips SM. Treadmill training-induced adaptations in muscle phenotype in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(1):61–68. doi: 10.1002/mus.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kyrolainen H, Kivela R, Koskinen S, McBride J, Andersen JL, Takala T, Sipila S, Komi PV. Interrelationships between muscle structure, muscle strength, and running economy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(1):45–49. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Macko RF, DeSouza CA, Tretter LD, Silver KH, Smith GV, Anderson PA, Tomoyasu N, Gorman P, Dengel DR. Treadmill aerobic exercise training reduces the energy expenditure and cardiovascular demands of hemiparetic gait in chronic stroke patients. A preliminary report. Stroke. 1997;28(2):326–330. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silver KH, Macko RF, Forrester LW, Goldberg AP, Smith GV. Effects of aerobic treadmill training on gait velocity, cadence, and gait symmetry in chronic hemiparetic stroke: A preliminary report. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2000;14(1):65–71. doi: 10.1177/154596830001400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny CL, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Silver KH. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(7):879–884. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith GV, Forrester LW, Silver KH, Macko RF. Effects of treadmill training on translational balance perturbation responses in chronic hemiparetic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebravasc Dis. 2000;9(5):238–245. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith GV, Silver KH, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. “Task-oriented” exercise improves hamstring strength and spastic reflexes in chronic stroke patients. Stroke. 1999;30(10):2112–2118. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith GV, Macko RF, Silver KH, Goldberg AP. Treadmill aerobic exercise improves quadriceps strength in patients with chronic hemiparesis following stroke: A preliminary report. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 1998;12(3):111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kadi F, Johansson F, Johansson R, Sjöström M, Henriksson J. Effects of one bout of endurance exercise on the expression of myogenin in human quadriceps muscle. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121(4):329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gerrits HL, Hopman MT, Offringa C, Engelen BG, Sargeant AJ, Jones DA, Haan A. Variability in fibre properties in paralysed human quadriceps muscles and effects of training. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445(6):734–740. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kjaer M, Mohr T, Biering-Sørensen F, Bangsbo J. Muscle enzyme adaptation to training and tapering-off in spinalcord-injured humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;84(5):482–486. doi: 10.1007/s004210100386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yan T, Hui-Chan CW, Li LS. Functional electrical stimulation improves motor recovery of the lower extremity and walking ability of subjects with first acute stroke: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Stroke. 2005;36(1):80–85. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149623.24906.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Levin MF, Hui-Chan CW. Relief of hemiparetic spasticity by TENS is associated with improvement in reflex and voluntary motor functions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;85(2):131–142. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90079-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ng SS, Hui-Chan CW. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with task-related training improves lower limb functions in subjects with chronic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2953–2959. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Spurlock DM, McDaneld TG, McIntyre LM. Changes in skeletal muscle gene expression following clenbuterol administration [abstract] BMC Genomics. 2006;7:320. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Signorile JF, Banovac K, Gomez M, Flipse D, Caruso JF, Lowensteyn I. Increased muscle strength in paralyzed patients after spinal cord injury: Effect of beta-2 adrenergic agonist. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(1):55–58. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]