Abstract

A 1.5-year-old female rabbit (doe) was presented with a 3-day history of lethargy, anorexia, and mild facial swelling. The animal died shortly after examination and severe, acute hemorrhagic pneumonia was noted grossly. An alphaherpesvirus consistent with leporid herpesvirus-4 was isolated and characterized from this animal. This is the first confirmed report of the disease in Canada.

Résumé

Pneumonie hémorragique et nécrosante aiguë, splénite et dermatite chez un lapin de compagnie causées par un herpèsvirus nouveau (herpèsvirus-4 léporidé). Une lapine âgée de 1,5 an a été présentée avec une anamnèse de 3 jours de léthargie, d’anorexie et d’enflure faciale légère. L’animal est mort peu de temps après l’examen et une pneumonie aiguë grave a été sommairement observée. Un alphaherpèsvirus conforme au herpèsvirus-4 léporidé a été isolé et caractérisé chez cet animal. Il s’agit du premier rapport confirmé de la maladie au Canada.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Naturally occurring herpesvirus infections are rare in domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculi). Infection of healthy domestic rabbits with a gammaherpesvirus, leporid herpesvirus-2 (LHV-2), has been documented (1); however, infected animals are asymptomatic. Further, O. cuniculi are not susceptible to gammaherpesvirus diseases of cottontail rabbits (Silvilagus spp.), such as those caused by infection with LHV-1 and LHV-3 (2,3). Encephalitis and death following infection with human herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), an alphaherpesvirus, have been described sporadically in pet rabbits and are associated with close contact with an infected human (4–7). In the early 1990’s two herpesvirus-like outbreaks with high mortality characterized by lesions of ulcerative dermatitis, pneumonia, splenic necrosis, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage were reported from commercial rabbitries in Alberta (8) and Saskatchewan (9), respectively. However, the causative agents were never isolated and fully characterized from either outbreak. A recent outbreak of herpesvirus infection and disease occurred in pet and meat rabbits in Alaska with significant mortality (10). Affected animals presented with conjunctivitis, subcutaneous swellings, lethargy, respiratory distress, and abortion. A novel alphaherpesvirus, termed leporid herpesvirus-4 (LHV-4), was isolated and characterized from that outbreak (11). This report describes a pet rabbit that was fatally infected with LHV-4; the first characterized and documented case of this infection in Canada.

Case description

A 1.5-year-old intact female New Zealand white rabbit weighing 4.9 kg was presented to a veterinary clinic with a 3-day history of lethargy, anorexia, and facial swelling. The animal appeared to be well managed with good nutrition and was fed a balanced pelleted rabbit chow produced by a local feedmill, crushed oats, fresh grass, lettuce, and hay harvested from the owner’s rural property. Water was provided ad libitum by water bowl. The affected animal was 1 of 6 on the property and the animals were housed in a large hutch on a grassy enclosure surrounded by a sturdy chain link fence. The enclosure was cleaned out frequently and fresh straw bedding provided, as needed. Chipmunks, other small mammals and occasionally birds were seen within the enclosure on a number of occasions and direct contact with other forms of wildlife could occur across the fence. Two dogs also resided on the property. None of the other rabbits were showing any abnormal clinical signs at the time the case animal was presented; however, the dam of the affected rabbit became ill 5 d later, developing depression, anorexia, and head and neck swelling. Although this second animal subsequently survived, it was blind on recovery and no further workup was done.

Upon clinical examination of the index case, the animal was noted to be tachypneic. Facial swelling was noted in the area of the right nares and upper lip. A 1-cm diameter crusted sore was noted on the nasal planum and excessive waxy debris was also present in the left ear. A presumptive diagnosis of Pasteurella multocida-induced pneumonia was made and the animal was treated with 30 mg/kg of chloramphenicol palmitate (Chlor-Palm 250; Vétoquinol, Lavaltrie, Quebec) and prescribed more of the same to be given by mouth every 12 h. Mineral oil was instilled into the left ear and mild bleeding and ulceration was noted when cleaning the debris out of the ear. Panalog ointment (Fort Dodge/Wyeth, Guelph, Ontario) was instilled into the ear and the animal was discharged. Approximately 30 min after leaving the clinic, the owner reported that the rabbit began choking and bleeding from the nose. The animal died shortly afterwards and was submitted for necropsy examination.

At necropsy, the rabbit was in good body condition with abundant internal fat stores. There was generalized purple-red mottling and petechiation of the lungs. The lungs were fleshy with multiple palpable small hemorrhagic nodules present throughout the parenchyma. The tracheal mucosa was mildly congested. Within the abdomen, the spleen was congested and there was transmural reddening of the caudal 2 cm of the ileum. A blood clot was present within the ileal lumen at the same level.

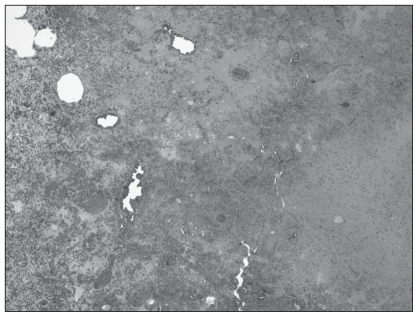

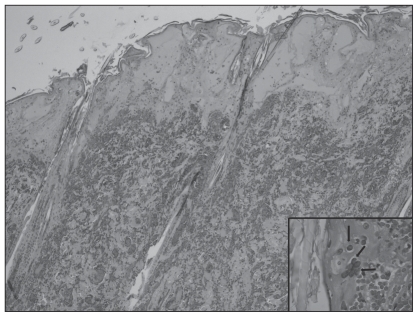

Microscopically, the most significant lesions were confined to the lungs, spleen, skin, and ileum. There was a marked, generalized necrotizing and hemorrhagic bronchopneumonia with denuding of airways and severe generalized alveolar flooding with edema fluid, fibrin, and infiltrating heterophils and macrophages (Figure 1). Numerous bronchiolar epithelial cells, pneumocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages contained prominent glassy eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusions and there was fibrinoid necrosis and thrombosis of several arterioles as well as fibrin thrombi. There was also massive fibrinohemorrhagic necrosis of the spleen with similar intranuclear inclusions in endothelial and stromal cells. The crusted mass on the face consisted of full thickness necrosis extending through the dermis with fibrinoid necrosis of smaller subtending arterioles, edema, and marked mixed infiltrates of heterophils and macrophages. Numerous epithelial and endothelial cells contained large, glassy eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions (Figure 2). There was transmural necrosis of the ileum with marked luminal hemorrhage, fibrin exudation, and bacterial overgrowth. The brain was not affected in this animal. Based on these findings, systemic infection with a lapine herpesvirus was suspected.

Figure 1.

Severe pulmonary hemorrhage, edema, and necrosis in lung sections from the rabbit that was presented with a history of lethargy, anorexia, and facial swelling. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E), ×40.

Figure 2.

Full thickness necrosis of facial skin, multinucleated giant cells, and typical glassy herpetic intranuclear inclusion bodies in epithelial cells (inset, arrows, ×650). H & E, ×40.

To characterize the virus, lung and skin samples were homogenized in virus transport media consisting of Hanks balanced salt solution with phenol red (Fisher, Whitby, Ontario), 0.5% lactalbumin hydrolysate (Fisher), HEPES (25 mM) (Fisher), penicillin: 62 500 units/500 mL (Fisher), and streptomycin: 62 500 μg/500 mL (Gibco Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario). The supernatant was filtered using a Millex 0.45 μm syringe filter (Fisher) and inoculated onto decanted tube monolayer cell cultures of rabbit kidney-13 cells grown in HMEM (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio, USA) with 10% fetal bovine sera (FBS) (PPA Laboratories, Etobicoke, Ontario), VERO cells grown in EMEM (Gibco Invitrogen), with 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco Invitrogen) and 10% FBS, Marden-Darby canine kidney cells grown in EMEM, with 1% lactalbumin hydrolysate, and Crandell feline kidney (CRFK) cells maintained in equal parts of IMDM (Gibco Invitrogen), EMEM and L-15 (Gibco Invitrogen) with 10% FBS. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h all cell monolayers were re-fed with similar maintenance media containing only 2% or 5% FBS. Infected and control uninfected tube cultures were examined daily under an inverted light microscope with phase contrast for cytopathic effect (CPE). Multinucleated giant cells and syncytia formation, a characteristic herpesvirus-induced CPE, was seen 3 d post-infection in CRFK cells only. Cell-associated viral particles were released by freezing and thawing the infected cells once. Negatively stained EM grids of virus particles were prepared and examined using a Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope. Ultrastructural examination demonstrated symmetrical icosahedral nucleocapsids approximately 100 nm in diameter, that were consistent with herpesvirus morphology and size. The virus-infected CRFK cell monolayers were negative in direct fluorescence antibody tests for canine and feline herpesviruses using monospecific reagents (VMRD, Pullman, Washington, USA).

For further characterization, the virus was propagated in CRFK cells and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted as described (12) and amplified by the primer sets indicated in Table 1, which were based on the ribonucleotide reductase (RR) gene sequences of LHV-4 and were designed to cover the entire 3391 base pairs (bp) gene (Figure 3B). The polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were made in 50 μL final volume with 1 × PCR buffer (200 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM KCl, pH 8.8), 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM dNTPs, 20 pmol of each primer, 2 U Pfu polymerase and 100 ng DNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles and a 10-minute final extension at 72°C. For each cycle, the denaturation occurred at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 54°C for 20 s and extension at 72°C for 3 min. Four DNA fragments were amplified and isolated (Figure 3A). The PCR products were purified, cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), and their sequences were determined at the Sequencing Facility of the Laboratory Services Division, University of Guelph and deposited to GenBank (accession number GQ413968). The sequences were compared to the GenBank database and there was 99% homology between the RR gene sequences of the recently described novel rabbit herpesvirus (LHV-4; accession number EU119871) (11) and sequences of our isolate from Ontario, designated LHV-4 ON1.

Table 1.

Forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sets for amplification of a novel rabbit herpesvirus ribonucleotide reductase gene

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Location | Purpose/Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1-F | ATGACGCCCACCAACGTCTC | 1–20 | F1 amplification |

| F1-R | CATAGACCGTAGGCGGTTC | 1599–1617 | F1 amplification |

| F2-F | GCACAGTGTGTGTTAGACG | 1471–1490 | F2 amplification |

| F2-R | ACGTGAACAGGAACCGGTAG | 2614–2633 | F2 and F4 amplification |

| F3-F | TGTGGCCAAGAACAACGATA | 2446–2465 | F3 and F4 amplification |

| F3-R | CTAGAGGTCGTTCACCACCG | 3372–3391 | F3 amplification |

Figure 3.

Panel A — Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of the PCR products (F1, F2, F3, and F4) following amplification of the entire ribonucleotide reductase gene of an Ontario rabbit herpesvirus, LHV-4 ON1. Lane M is a 1-kb DNA ladder. Panel B — Location of the 4 overlapping PCR fragments of the ribonucleotide reductase gene of LHV-4 ON1.

Discussion

Herpesviruses are categorized into subfamilies; alpha, beta, and gamma, largely based on the rapidity of viral replication and cytopathic effects. Alphaherpesviruses typically demonstrate rapid replication and are highly pathogenic to permissive cells following infection. The recent description of a leporid herpesvirus-4 outbreak in domestic rabbits from Alaska characterized by swift disease onset with high mortality is suggestive of an alphaherpesvirus classification, as is the rapid progression of disease in this case. In both reports, vasculitis was a prominent microscopic feature of the disease with facial swelling and hemorrhagic and necrotizing lesions found in the spleen, lung, and skin of infected animals.

Encephalitis is commonly seen in experimental herpetic infections of rabbits (13) as well as natural disease induced by HSV-1 infection in domestic rabbits (6,7). Brain was not examined in the Alaskan cases (10) and neurologic lesions were not noted in tissue from the current case. Moreover, PCR primers specific for the polymerase gene of HSV-1 did not amplify this new Ontario rabbit isolate (LHV-4 ON1). Interestingly, CNS changes were not noted in the 2 untyped herpesvirus cases with high mortality reported in commercial rabbits from Canada in the 1990’s (8,9). A lack of nervous system tropism may be a feature of infection with LHV-4, distinguishing it from infection with HSV-1 in rabbits.

In the current report, 2 of 6 pet rabbits were presented moribund. Up to 50% morbidity and 29% mortality were observed in the other confirmed report of LHV-4 in rabbits (10). Factors contributing to disease susceptibility and resistance are undefined; however, all cases of LHV-4 infection, both confirmed and suspected, have occurred in the summer months (8–10). It is not known if heat stress exacerbates viral infection or actinic exposure reactivates latent herpetic infection.

Other potential differential diagnoses that should be considered in cases in which pet or commercial rabbits are presented with clinical signs of subcutaneous facial swellings, respiratory distress, or epistaxis include several other viral diseases and bacterial infections. Reports of naturally occurring viral infections inducing clinical disease and death in domestic rabbits are extremely rare in Canada. Neither of the 2 major rabbit viruses that induce high mortality worldwide in O. cuniculi, rabbit viral hemorrhagic disease virus (VHDV; a calicivirus) and myxomatosis virus (a poxvirus), have ever been reported in Canadian pet or commercial rabbits. Both of these viral infections induce a spectrum of clinical signs that could overlap with signs noted in this case and these should be considered potential differentials in similar cases. Viral hemorrhagic disease virus induces rapid multi-organ endothelial damage and hemorrhage that may present as epistaxis, tachypnea, and sudden death, while myxomatosis may present as an acute onset of subcutaneous edema with crusting, lethargy, anorexia, and sudden death. Viral hemorrhagic disease virus has occurred sporadically in commercial US rabbitries (14), as recently as 2005, while myxomatosis is considered enzootic in cottontail rabbits in parts of California with rare occurrences in domestic rabbits (15).

Pasteurella multocida infection is highly prevalent in domestic rabbits in Canada and infected animals may be presented with oculonasal discharge, otitis media, rhinitis, and pneumonia in addition to subcutaneous and systemic abscesses (16). Animals may die suddenly from peracute infections or from ruptured pleural or pulmonary abscesses and this agent should always be considered as a primary differential for rabbits in respiratory distress. Less common causes of bacterial pneumonia in rabbits include Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bordetella bronchiseptica.

In summary, a novel leporid herpesvirus infection consistent with LHV-4 is confirmed and reported for the first time in a Canadian rabbit. The infection produced fulminant disease, characterized by skin lesions, signs of respiratory distress, epistaxis, lethargy and anorexia, culminating in death. Further work needs to be conducted to determine the prevalence of the disease in Canadian rabbit populations, including susceptibility of Silvilagus spp. to infection, as well as factors that may enhance disease susceptibility and resistance. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Zygraich N, Berge E, Brucher JM, Hoorens J, Huygelen C. Experimental infection of rabbits and monkeys with Herpesvirus cuniculi. Res Vet Sci. 1972;13:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hesselton RM, Yang WC, Medveczky P, Sullivan JL. Pathogenesis of Herpesvirus sylvilagus infection in cottontail rabbits. Am J Pathol. 1988;133:639–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt SP, Bates GN, Lewandoski PJ. Probable herpesvirus infection in an eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) J Wildl Dis. 1992;28:618–622. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grest P, Albicker P, Hoelzle L, Wild P, Pospischil A. Herpes simplex encephalitis in a domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) J Comp Pathol. 2002;126:308–311. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2002.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissenböck H, Hainfellner JA, Berger J, Kasper I, Budka H. Naturally occurring herpes simplex encephalitis in a domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) Vet Pathol. 1997;34:44–47. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller K, Fuchs W, Heblinski N, et al. Encephalitis in a rabbit caused by human herpesvirus-1. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235:64–69. doi: 10.2460/javma.235.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruber A, Pakozdy A, Weissenböck H, Csokai J, Kunzel DF. A retrospective study of neurological disease in 118 rabbits. J Comp Path. 2009;140:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swan C, Perry A, Papp-Vid G. Alberta. Herpesvirus-like viral infection in a rabbit. Can Vet J. 1991;32:627–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onderka DK, Papp-Vid G, Perry AW. Fatal herpesvirus infection in commercial rabbits. Can Vet J. 1992;33:539–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin L, Valentine BA, Baker RJ, et al. An outbreak of fatal herpesvirus infection in domestic rabbits in Alaska. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:369–374. doi: 10.1354/vp.45-3-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin L, Löhr CV, Vanarsdall AL, et al. Characterization of a novel alpha-herpesvirus associated with fatal infections of domestic rabbits. Virol. 2008;378:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagy É, Idamakanti N, Carman S. Restriction endonuclease analysis of equine herpesvirus-1 isolates recovered in Ontario 1986–1992 from aborted, stillborn and neonatal foals. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1997;9:143–148. doi: 10.1177/104063879700900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Päivärinta MA, Marttila RJ, Lönnberg P, Rinne UK. Decreased raphe serotonin in rabbits with experimental herpes simplex encephalitis. Neurosci Lett. 1993;156:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90424-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campagnolo ER, Ernst MJ, Berninger ML, Gregg DA, Shumaker TJ, Boghossian AM. Outbreak of rabbit hemorrhagic disease in domestic lagomorphs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;223:1151–1155. 1128. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.223.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton NM, Holmes HT. Myxomatosis in domestic rabbits in Oregon. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977;171:560–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell; 2007. [Google Scholar]