Abstract

Severe meningoencephalitis and endometritis associated with necrotizing vasculitis, thrombosis, and infarction were found at necropsy of a 4-year-old Aberdeen Angus cow with a history of abortion and neurological signs. Focal pyogranulomatous pneumonia and nephritis were also present. Fungal hyphae typical of zygomycetes were abundant within lesions, and Mortierella wolfii was cultured from multiple tissues. This is believed to be the first report of systemic mortierellosis following abortion in North America, and the second reported instance of encephalitis caused by M. wolfii in a cow.

Résumé

Infection systémique par Mortierella wolfii suivie d’un avortement chez une vache. Une méningoencéphalite et une endométrite graves associées à une vasculite nécrosante, à la thrombose et à des infarcti ont été constatés chez une vache Aberdeen Angus âgée de 4 ans avec des antécédents d’avortement et de signes neurologiques. Une pneumonie pyogranulomateuse focale et une néphrite étaient aussi présentes. Des hyphes fongiques typiques des zygomycètes étaient abondants dans les lésions et Mortierella wolfii a été cultivé dans de nombreux tissus. On croit qu’il s’agit du premier rapport de mortierellose systémique après l’avortement en Amérique du Nord et le deuxième cas signalé d’encéphalite causé par M. wolfii chez une vache.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Mycotic infection is an important cause of bovine abortion in many countries, including Canada (1,2). The zygomycete Mortierella wolfii has been implicated in a large proportion of mycotic abortions in areas of New Zealand where it is associated with a “distinctive mycotic abortion-pneumonia syndrome” (3,4). Infection with this fungus is apparently uncommon in cattle elsewhere. To our knowledge, the case reported here is the first report of M. wolfii infection in Canada, and the first report of systemic mortierellosis in an adult bovine in North America.

Case description

A 4-year-old Aberdeen Angus cow from west-central Saskatchewan was submitted during February, 2002 to Prairie Diagnostic Services Inc. at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan for postmortem examination. She had shown clinical signs of lethargy, anorexia, ataxia, and blindness prior to euthanasia, and had aborted recently at approximately 5 mo gestation. A left shift with a band neutrophil count of 0.611 × 109/L (normal range: 0.000 to 0.120 × 109/L) and mild toxic change were detected in blood collected prior to euthanasia. The total solids to fibrinogen ratio was 8:1 indicating hyperfibrinogenemia.

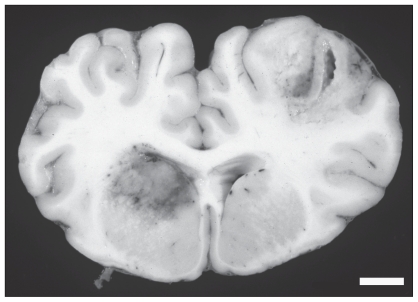

At necropsy, the carcass was fresh and the cow was in good nutritional condition. Significant lesions were restricted to the brain, uterus, lungs, and kidneys. In the brain, there were multifocal adhesions of the leptomeninges to the dura mater over the left and right cerebral hemispheres. The leptomeninges in these areas were thickened, red, and opaque, and purulent material was present. Sectioning of the brain revealed 4, randomly distributed, 1- to 3-cm areas of malacia and hemorrhage predominantly in the gray matter of the cerebral cortex and corpus striatum (Figure 1). Some of these lesions were cavitated. The right horn of the uterus was 20 cm in diameter and contained foul-smelling retained placental remnants; no fetus was present. The endometrium was diffusely thickened, reddened and covered by necrotic debris. There were several, randomly scattered, 1- to 4-mm, white nodules within the kidneys and lungs. Representative tissue samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h, processed routinely for histological examination and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Grocott’s modification of Gomorri’s methenamine silver method with H & E counterstain (5) was used on selected tissues. Fresh sections of the brain, the retained placenta, and the kidney were submitted for routine culture.

Figure 1.

Two large foci of hemorrhage and malacia involve the cerebral cortex and corpus striatum. Bar = 1 cm.

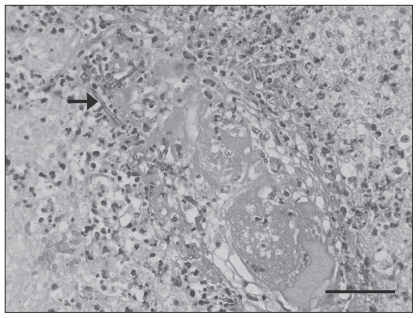

Microscopic lesions within the brain were most notable in the cerebrum and corpus striatum and extended into the leptomeninges. In affected areas, up to 80% of the normal tissue architecture was obscured by foci of neuronal necrosis and rarefaction of the neuropil, surrounded by an intense band of degenerate neutrophils admixed with macrophages; reactive astrocytes were present. In these areas, there was severe necrotizing vasculitis, characterized by fibrinoid change within the vessel wall, accumulation of nuclear debris and degenerate neutrophils (Figure 2). Vessels frequently contained thrombi. Many fungal hyphae were seen within the thrombi, in the vessel walls, and within the necrotic foci. The hyphae were rarely septate, up to 20 μm wide with bulbous dilations with non-parallel walls and wide angle branching consistent with zygomycete fungi (6) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph demonstrating necrotizing vasculitis, thrombosis, and numerous fungal hyphae (arrow) in the brain. Grocott’s modification of Gomori’s methenamine-silver method, with hematoxylin and eosin counterstain. Bar = 50 μm.

Necrotizing vasculitis and extensive tissue necrosis associated with similar fungal hyphae were present in the endometrium. The renal and pulmonary nodular masses seen grossly represented 1- to 4-mm foci of pyogranulomatous inflammation centered on aggregates of similar fungal hyphae. Vasculitis with ischemic necrosis was not a prominent feature in these tissues. Fungal elements in the kidney were surrounded by radiating, club-shaped, aggregations of brightly eosinophilic material consistent with Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.

Brain, kidney, and placental remnants were cultured on blood and MacConkey agar plates (Becton Dickinson and Company, Sparks, Maryland, USA). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 or anaerobically (blood agar plates) or normal atmosphere (MacConkey agar plates). Blood agar cultures resulted in heavy growth of mold (4+), alpha Streptococcus species (3+), gram-negative anaerobic rods (3+) and Escherichia coli (3+) from the brain; moderate growth of mold (2+) and light growth of E. coli (1+) from the kidney; and moderate growth of alpha Streptococcus species (2+) from the placenta. Light growth of E. coli (1+) was observed on MacConkey agar plates from brain and kidney. The mold was subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Becton Dickinson) and incubated at ambient (room) temperature for 3 d. It grew rapidly and produced white, velvety mycelium that was examined under a light microscope after staining with lactophenol cotton blue dye, using a sticky tape preparation. The organism was identified as Mortierella wolfii based on cultural characteristics, colony morphology, and examination of hyphae and sporangiospores (7).

Discussion

This cow had systemic mycosis with significant lesions in the brain that accounted for the neurological deficits. The morphological features of the hyphae were consistent with zygomycete fungi and M. wolfii was identified on culture, leading to a final diagnosis of mortierellosis. Given the history of recent abortion, the presence of mycotic endometritis, and the known behavior of M. wolfii, we believe this to be an example of primary mycotic endometritis and fungal abortion leading to hematogenous dissemination of the organism with development of embolic meningoencephalitis, pneumonia and nephritis.

Mycotic placentitis is a worldwide cause of abortion in cattle that is usually sporadic within the herd and generally occurs in the third trimester (1,2). In the Northern hemisphere, mycotic abortion in cattle is encountered most often between November and April; the time of year when gravid cows are most likely to be housed indoors and fed moldy hay or ensilage (1,8). In North America, mycotic infection is associated with a variety of fungal organisms, and has been estimated to cause 3.2% to 6.8% of bovine abortions (1,9–11). Aspergillus spp. are the agents identified most commonly and are responsible for approximately 71% of mycotic abortions (1). Members of the class Zygomycetes, including the genera Absidia, Mortierella, Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Rhizopus, are responsible for an estimated 21% of mycotic abortions in cattle (1). Mortierella wolfii was identified in 0.4% of cases of mycotic abortion in cattle in 1 survey in the United States, but subsequent maternal disease has not been reported (1,12). To the authors’ knowledge, M. wolfii infection has not been reported as a cause of mycotic abortion or maternal disease in Canada.

The situation in North America is in striking contrast to regions of New Zealand where M. wolfii is the most important cause of fungal abortion in cattle and is the etiologic agent in up to 46% of cases of mycotic placentitis (3). Mortierella wolfii infection there is seen almost exclusively in dairy cows, and is typically associated with feeding moldy hay and ensilage, resulting in abortion between 5 mo gestation and term (3). While maternal disease is not observed in most cases of fungal abortion (2), approximately 20% of cows that abort from M. wolfii infection develop acute fatal pneumonia as a sequel to placentitis (13). It is suggested that fungal spores gain access to the venous blood or lymphatics through the respiratory system, alimentary tract, conjunctiva, or skin wounds. The organism then follows a lung-uterus-lung cycle. Spores in the lungs pass through the pulmonary capillaries and enter the arterial system, with hematogenous spread to the placentome resulting in placentitis, endometritis, and subsequent abortion 2 to 5 wk post-infection. At the time of abortion, large numbers of fungi re-enter circulation, resulting in acute embolic pneumonia in the dam within 4 d of the abortion (14).

It appears that M. wolfii infection occurs primarily in pregnant animals, with only a few reports of infection of lung (15) and liver (7) in non-pregnant, adult cows. Why pregnant cows are particularly susceptible is not known, but the placentome may possess physical and chemical properties that favor the germination of M. wolfii spores (14). Why only some cows with mycotic placentitis and endometritis develop fatal embolic pneumonia is also unknown. Healthy humans appear to have strong natural immunity to zygomycosis but conditions that result in decreased production or function of macrophages and/or neutrophils may result in invasive fungal disease (6,16). Risk factors in humans include diabetes, malignancies, solid organ transplantation, bone marrow transplantation, iron chelator therapy, and intravenous drug use (6,16,17). No condition that could account for immune system impairment was identified in the cow we described.

This case of mortierellosis is unusual in that the cow had neurological disease and severe lesions in the brain, but had minimal lung involvement. In most cases of bovine mortierellosis, lesions are rare in organs other than the lung and uterus (14). There is only one prior report of M. wolfii causing meningoencephalitis in an adult cow (18). It was hypothesized that after abortion, fungi re-entered the circulation resulting in embolic showering of the brain in that animal (18). A similar pathogenesis is suspected in the present case. Zygomycosis involving the central nervous system (CNS) has been reported in humans and most commonly is a result of direct extension from the nasal cavity or sinuses (6,16,17). Cerebral zygomycosis as a result of hematogenous dissemination is less common and in these cases most lesions are in the basal ganglia, reflecting the propensity of particulate material the size of spores to be distributed to the gray-white junction of the brain and to the basal ganglia via the striatal arteries (17). Involvement of the corpus striatum, which houses the basal ganglia, was a prominent feature in the cow we described.

In conclusion, this appears to be the first reported case of mortierellosis in Canada and the first report of systemic disease caused by M. wolfii in an adult cow in North America. It is the second report of encephalitis caused by M. wolfii in a mature cow. Based on published literature, disease attributed to M. wolfii infection is uncommon in cattle in North America, compared with some other parts of the world. The reasons for this geographic variability are unknown but might reflect differences in prevalence of the organism in the environment, animal husbandry, and feed management. While M. wolfii must be considered a rare cause of bovine abortion and systemic mycosis in Canada, the prevalence may have been underestimated because M. wolfii is difficult to isolate from contaminated material (3). Mortierellosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in mature cows presenting with systemic disease following abortion.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Jennifer Cowell for her valuable technical assistance. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Knudtson WU, Kirkbride CA. Fungi associated with bovine abortion in the northern plains states (USA) J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:181–185. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, editor. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 429–564. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter ME, Cordes DO, Di Menna ME, Hunter R. Fungi isolated from bovine mycotic abortion and pneumonia with special reference to Mortierella wolfii. Res Vet Sci. 1973;14:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbel MJ, Eades SM. Observations on the experimental pathogenicity and toxigenicity of Mortierella wolfii strains of bovine origin. Br Vet J. 1991;147:504–516. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(91)90020-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheehan DC, Hrapchuk BB. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 1980. p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:236–301. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.236-301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzal FA, Connole MD, O’Boyle D, Dobrenov B, Kelly WR. Mortierella wolfii isolated from the liver of a cow in Australia. Vet Rec. 1999;145:260–26. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.9.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constable PD. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs and Goats. 10th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 1471–1474. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves D, McEwen B, Hazlett M, Maxie G, Anderson N. Trends in bovine abortions submitted to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, 1993–1995. Can Vet J. 1996;37:287–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkbride CA. Etiologic agents detected in a 10-year study of bovine abortions and stillbirths. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:175–180. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khodakaram-Tafti A, Ikede BO. A retrospective study of sporadic bovine abortions, stillbirths, and neonatal abnormalities in Atlantic Canada, from 1990–2001. Can Vet J. 2005;46:635–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wohlgemuth K, Knudtson WU. Abortion associated with Mortierella wolfii in cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977;171:437–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordes DO, Dodd DC, O’Hara PJ. Acute mycotic pneumonia of cattle. N Z Vet J. 1964;12:101–104. doi: 10.1080/00480169.1964.33562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordes DO, Carter ME, Di Menna ME. Mycotic pneumonia and placentitis caused by Mortierella wolfii. II. Pathology of experimental infection in cattle. Vet Pathol. 1972;9:190–201. doi: 10.1177/030098587200900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabor LJ. Mycotic pneumonia in a dairy cow caused by Mortierella wolfii. Aust Vet J. 2003;81:409–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb11548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown J. Zygomycosis: An emerging fungal infection. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62:2593–2596. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan W, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munday JS, Laven RA, Orbell GMB, Pandey SK. Meningoencephalitis in an adult cow due to Mortierella wolfii. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006;18:619–626. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]