SUMMARY

Globally, the mental health system is being transformed into a strengths-based, recovery-oriented system of care, to which the concept of active living is central. Based on an integrative review of the literature, this paper presents a heuristic conceptual framework of the potential contribution that enjoyable and meaningful leisure experiences can have in active living, recovery, health and life quality among persons with mental illness. This framework is holistic and reflects the humanistic approach to mental illness endorsed by the United Nations and the World Health Organization. It also includes ecological factors such as health care systems and environmental factors as well as cultural influences that can facilitate and/or hamper recovery, active living and health/life quality. Unique to this framework is our conceptualization of active living from a broad-based and meaning-oriented perspective rather than the traditional, narrower conceptualization which focuses on physical activity and exercise. Conceptualizing active living in this manner suggests a unique and culturally sensitive potential for leisure experiences to contribute to recovery, health and life quality. In particular, this paper highlights the potential of leisure engagements as a positive, strengths-based and potentially cost-effective means for helping people better deal with the challenges of living with mental illness.

Keywords: culture, recreation, mental health, quality of life

LEISURE AS A CONTEXT FOR ACTIVE LIVING, RECOVERY, HEALTH AND LIFE QUALITY FOR PERSONS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT

Globally, mental disorders are prevalent across all cultures—more than 450 million people suffer from mental disorders worldwide (Hyman et al., 2006). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2001a) estimated that mental disorders would account for 15% of the total burden of disease in the year 2020, and showed that mental disorders would be the principal cause of Years Lived with Disability internationally. Despite advances in pharmacological and psychosocial treatments, the quality and adequacy of health care for persons with mental illness ‘remain fragmented, disconnected, and often inadequate, frustrating the opportunity for recovery’ (New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003, p. 1).

Within Transforming Mental Health Care in America, Federal Action Agenda, recovery is emphasized as the single most important goal for the mental health system (USDHHS, 2006). Also, as a follow-up to the 2001 World Health Report, the mental health Global Action Programme (mhGAP) was developed and provides a strategy for closing the gap between what is urgently needed and what is currently available to help individuals and families affected by mental illness (WHO, 2001a). Achieving the highest level of recovery was identified as a major goal of the mhGAP (WHO).

RECOVERY DEFINED

According to the National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery, derived from over 110 expert panelist deliberations, recovery is defined as ‘a journey of healing and transformation enabling a person with a mental health problem to live a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential’ (USDHHS, 2006). Recovery involves a holistic, person-centered, strengths-based approach that focuses on: self-direction, respect, hope, connectedness, peer support, empowerment, spiritual fulfillment and meaningful life (including education, employment and leisure) (Sells et al., 2006; USDHHS, 2006). The practical use of these key elements of recovery (e.g. hope as the very idea that recovery is possible) was emphasized in Sartorius and Schulze's (Sartorius and Schulze, 2005) document based on reports from the World Psychiatric Association's effort to fight against stigma of mental illness.

Understanding the true meaning and essence of recovery as an expectation for and by people with mental illness is a global concern. Davidson and Roe conducted an extensive review of the empirical literature on recovery from an international perspective (Davidson and Roe, 2007). They identified two complementary meanings of recovery—‘The first meaning of recovery from mental illness derives from over 30 years of longitudinal clinical research, which has shown that improvement is just as common, if not more so, than progressive deterioration. The second meaning of recovery in derives from the Mental Health Consumer/Survivor Movement, and refers instead to a person's rights to self-determination and inclusion in community life, despite continuing to suffer from mental illness’ (p. 459).

Ramon et al. also surveyed the meanings of the term recovery from a global perspective, with particular attention given to service users' definitions (Ramon et al., 2007). They concluded, ‘Recovery is not about going back to a pre-illness state, and means something very different from the ‘old’ emphasis on controlling symptoms or cure. Rather, it is a complex and multifaceted concept, both a process and an outcome, the features of which include strength, self-agency and hope, interdependency and giving, and systematic effort, which entails risk-taking’ (p. 119).

RE-DEFINING ACTIVE LIVING

The concept of recovery is based on a vision that a majority of people with mental illness can lead meaningful lives in their community (Clay et al., 2005). Within the USA, active living is a public health issue and its health benefits have been well documented. Beneficial outcomes include improved health (Tudor and Bassett, 2004), physical functioning (Brach et al., 2004), health-related quality of life (Brown et al., 2004) and lower mortality (Gregg et al., 2003). However, active living is typically understood from a physical activity/exercise perspective. This is increasingly the case in an international context, as well (e.g. Murray, 2006; Carless, 2007). While physical activity and exercise is undeniably a core component in active living, there is a risk of over-emphasizing physical activity as the defining element of active living. This creates a biased view of active living by overlooking the potential value of other types of activities that promote active engagement in one's life, such as non-physical or less physically demanding forms of leisure (e.g. expressive/creative, social, spiritual or cultural forms of leisure).

We propose a broader and more strength-based, humanistic approach to the conceptualization of active living. This conceptualization views active living as being actively engaged in living all aspects of one's life both personally and in families and communities in a meaningful and enriching way rather than the narrower conceptualization of active living, which is predominately biased toward physical activity and exercise only (Iwasaki et al., 2006; Kaczynski and Henderson, 2007). Both the United Nations (UN; Quinn et al., 2002) and World Health Organization (WHO, 2005) support such a conceptualization, given their endorsement of a broad and strengths-based, human rights approach to health promotion among global populations (including individuals with disabilities such as mental illness) in both developing and developed countries.

A broader conceptualization of active living may be particularly salient to persons with mental illness not only because sedentary and inactive lifestyles are prevalent among this population group (McElroy et al., 2006), but also because their lives are often characterized by loneliness and isolation and a disconnection from their community (Lemaire and Mallik, 2005). A conceptualization of active living that is attentive to the humanistic as well as physical outcomes derived from activity may be more effective in this population, especially since it can embrace the individual's need for meaning-seeking or -making. Examples of activities that illustrate this conceptualization of active living would include: (a) Tai Chi, a physical activity that promotes physical health but which also focuses on body-mind-spirit harmony; (b) social leisure activities with peers/friends that promote emotional health and which do not emphasize living with mental illness as an issue (i.e. stigma); and (c) culturally meaningful, spiritually refreshing and/or creative/expressive leisure activity such as art/crafts, music and dance that promote self-expression and identity.

ENJOYABLE AND MEANINGFUL LEISURE AS A CONTEXT FOR ACTIVE LIVING

In this paper, leisure is defined as a relatively freely chosen humanistic activity and its accompanying experiences and emotions (e.g. enjoyment and happiness) that can potentially make one's life more enriched and meaningful. The meaning-seeking or meaning-making functions of leisure have a long tradition in the leisure research field (e.g. Shaw, 1985; Samdahl, 1988; Henderson et al., 1996; Kelly and Freysinger, 2000). Recently, Iwasaki (Iwasaki, 2008) identified key pathways to meaning-making through leisure-like pursuits in global contexts. He showed that in people's quest for a meaningful life, these leisure-generated pathways seem to simultaneously involve both ‘remedying the bad’ (e.g. coping with/healing from stressful or traumatic experiences, reducing suffering) and ‘enhancing the good’ (e.g. promoting life satisfaction and life quality) through facilitating, for example, positive emotions, identities, spirituality, connections and a harmony, human strengths and resilience, and learning and human development across the lifespan. Overall, these notions of leisure emphasize: (a) meaning-oriented emotional, spiritual, social and cultural properties of leisure that reflect a broader and humanistic perspective than physical activity alone, and (b) the role of meaning-making through leisure in promoting active living, health and life quality for people including individuals with mental illness. Leisure is a key context for active living and an important pathway toward recovery, health promotion and life-quality enhancement. Leisure represents broad aspects of human functioning including emotional, spiritual, social, cultural and physical elements. The forms that leisure expressions take (e.g. sport, exercise, art, crafts, visits with friends) are secondary to the meanings derived from and associated with the leisure experiences, and it is the outcomes/meanings derived that present the potential contributions to these pathways.

Recent research has shown that leisure opportunities (e.g. through a peer-run program at recreation centers) can play a key role in the recovery of persons with mental illness (Swarbrick and Brice, 2006). Davidson et al.'s multinational study on recovery from serious mental illness highlighted the importance of going out and engaging in ‘normal’ activities, and having meaningful social roles and positive relationships outside of the formal mental health system (Davidson et al., 2005) . Not only can leisure and recreation provide an opportunity for going out and socially valued normal activities, but these activities can also provide a context for having a positive relationship and pursuing a meaningful social role among people including individuals with disabilities (Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2006; Hutchinson et al., 2008). Fullagar's qualitative study with 48 women with depression in Australia found that creative (e.g. art/craft, gardening, writing, music), actively embodied (e.g. walking, yoga, Tai Chi, swimming) and social (e.g. cafes, friend/support groups) leisure activities acted as a counter-depressant by eliciting positive emotions (e.g. joy, pleasure, courage) that facilitated recovery and transformation in ways that biomedical treatments could not (Fullagar, 2008). These findings show important practical implications that advocate a more humanistic, strengths-based and potentially cost-effective health-care approach.

PURPOSE STATEMENT

Unfortunately, active living and health promotion research for individuals with mental illness has never directly integrated the concept of recovery. Conceptualizing active living from a broader, humanistic and meaning-oriented perspective is proposed as being preferable over a narrow single-dimensional (e.g. physical activity) perspective. Also, leisure pursuits seem to provide an important context for active living and recovery-oriented health and life-quality promotion (Godbey et al., 2005; Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005; Sallis et al., 2005). This potential, however, has been neglected (and perhaps undervalued) and seldom studied directly. Therefore, based on an integrative review of the literature, this paper presents a heuristic conceptual framework of the potential role of enjoyable and meaningful leisure in facilitating active living, recovery and health/life-quality promotion among persons with mental illness from a more holistic/ecological and humanistic perspective in a global cross-cultural context. Holistic and ecological concepts supported by Ng et al. (Ng et al., 2009), DeLeon (DeLeon, 2000) and Bambery and Abell (Bambery and Abell, 2006) are a basis of our framework.

First, inspired by Chinese medicine's holistic model, Ng et al. (Ng et al., 2009) conceptualized an Eastern body-mind-spirit approach to achieving a primary therapy goal of facilitating a harmonious equilibrium within oneself as well as between oneself and the natural and social environment. Advocating the notion of ‘beyond survivorship,’ this approach focuses on human strengths and thriving. For example, in this approach, striving for a vibrant mind/spirit is pursued through Tai Chi and Qigong exercises, which enable one to appreciate and affirm one's life through meaning-making, which can be a catalyst to transform clients for positive change. The aim of this holistic approach is to activate an interconnected body-mind-spirit system in order to reestablish a balance and harmony among clients contextualized within their broader community, society and environment.

DeLeon's Therapeutic Community (TC) model is also relevant to this holistic and ecological concept (DeLeon, 2000). The TC model is more comprehensive and integrative than those based on symptom reduction alone. It emphasizes the transformative influences of one's identity and culture through collective intervention formats using the power of social groups in augmenting active learning, personal and social responsibility, and collective growth. DeLeon's TC model aims to achieve an existentially derived and authentic purpose in life as the primary value of living, which he theorizes to include personal and social accountability, collective learning, community involvement and good citizenry within a broad societal system. These concepts are also in line with Bambery and Abell's (Bambery and Abell, 2006) urge for shifting the mental health field's current paradigm of psychopathology to a more holistic and ecological perspective by supporting Fromm's (Fromm, 1941, 1955, 1976) advocacy for a more comprehensive treatment of individuals including its sensitivity to a macro-context in which society (e.g. culture, historical forces, social class) influences one's behavior. These notions are further supported by Bambery and Abell's case study that addressed both individual psychopathology and larger societal ills influencing their study participants' lives including family, social and environmental factors from an ecological perspective.

TOWARD A HOLISTIC/ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE ROLES OF LEISURE IN ACTIVE LIVING, RECOVERY AND HEALTH/LIFE-QUALITY PROMOTION AMONG PERSONS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

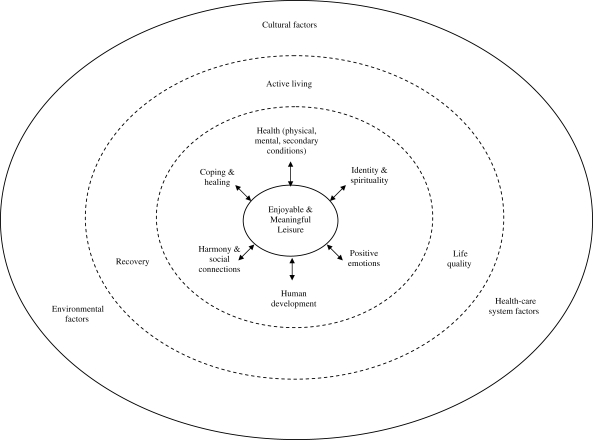

Using a holistic and ecological perspective, our proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1) depicts the potential interrelationships among active living, recovery and health/life quality among people with mental illness. These potential pathways were derived from an extensive and comprehensive review of the literature including both qualitative and quantitative data from studies conducted in a cross-cultural, international context.

Fig. 1:

A heuristic holistic/ecological framework of the roles of leisure in active living, recovery and health/life-quality promotion among persons with mental illness. Broken lines (---) represent transactional reciprocal relationships and connectedness between the various factors depicted in the framework.

In this framework, enjoyable and meaningful leisure expressions are emphasized as a key context for active living, and as a major pathway to recovery, health and life quality. We recognize that other activities (e.g. employment) also contribute to active living and the reader should not think that we are placing leisure as the sole construct contributing to active living. Rather, this conceptual framework is developed to highlight how enjoyable and meaningful leisure, an often neglected life activity in the rehabilitation process, can and should be considered when designing interventions to promote active living, recovery and health/life quality for individuals with mental illness.

As depicted with bi-directional arrows, enjoyable and meaningful leisure is assumed to function as a critical proactive agent via its potential to promote personal identity and spirituality, positive emotions, harmony and social connections, effective coping and healing, human development, and physical and mental health. The bi-directional arrows also indicate the converse that personal identity and spirituality, harmony and social connections, coping and healing, etc., in turn, influence leisure expressions.

The circular structure in our framework illustrates a system of micro and macro factors from a holistic/ecological perspective. The factors within the outer circle (i.e. cultural, environmental and health-care system factors) are considered more macro than the factors within the inner circle. Also, both the distinction and interconnectedness between micro and macro factors are implied. For example, personal identity and spirituality as a micro element are located within the inner circle along with other potential leisure outcomes such as positive emotions, harmony and social connections, coping/healing and health, which are distinguished from (yet are connected to) cultural factors as a macro element. On the other hand, active living, recovery and life quality are highlighted as key leisure-generated outcomes, contextualized within the outer layer of macro factors (i.e. cultural, environmental and health-care system factors). These transactional reciprocal relationships and connectedness between the various factors within multiple layers of circles are depicted with broken lines (---) of circles in the conceptual framework. It must, however, be cautioned that our intention here is not to suggest causation. Rather, our conceptual framework is presented as a ‘heuristic’ map to stimulate a more balanced, holistic/ecological and humanistic orientation of practice toward active living, recovery and the promotion of health and life quality among culturally diverse groups of people with mental illness in a global context. It is also recognized that this reciprocal transaction can be both positive and negative. That is, discretionary time behaviors (leisure) can be detrimental to health just as environmental factors can support or impede meaningful leisure experiences. Nevertheless, this article focuses on ideal transaction.

POTENTIAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF LEISURE TO ACTIVE LIVING, RECOVERY AND HEALTH/LIFE QUALITY AMONG PEOPLE WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

Leisure's potential has increasingly been shown in a series of empirical research. For example, Lloyd et al.'s (Lloyd et al., 2007) study with 44 Australian clubhouse members with mental illness found a significant association between leisure motivation (measured with leisure motivation scale, Beard and Ragheb, 1983) and recovery (measured with recovery assessment scale, Corrigan et al., 2004). Specifically, individuals who were motivated to engage in leisure were functioning well at a higher level of recovery, while goal- and success-oriented leisure motivation (r = 0.84) and leisure motivation toward personal confidence and hope (r = 0.83) had strongest correlations with recovery. These findings are consistent with Hodgson and Lloyd's (Hodgson and Lloyd, 2002) qualitative study showing that the involvement in leisure activities plays a vital role in relapse prevention for individuals with dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance misuse, and with Moloney (Moloney, 2002) and Ryan (Ryan, 2002) who emphasized that the engagement in leisure is instrumental in a journey for recovery from a consumer perspective. Trauer et al.'s study with 55 clients with serious mental illness reported that one's satisfaction with leisure had the strongest association with global well-being (GWB) (r = 0.76) (Trauer et al., 1998). This association between leisure satisfaction and GWB was greater than any other life-domain measures such as health, family and social relations. Also, Lloyd et al.'s (Lloyd et al., 2001) study found that individuals with mental illness who participated in a community-based rehabilitation program reported positive effects of leisure on intellectual stimulation, relaxation and enjoyable relationships with others. By integrating the findings of these studies, Lloyd et al. (Lloyd et al., 2007) emphasized that leisure-based programs should be considered for community reintegration and social inclusion of people with mental illness. This recommendation is in line with Heasman and Atwal's (Heasman and Atwal, 2004) finding that leisure participation can contribute to greater social inclusion among British adults with mental illness.

Frances' (Frances, 2006) evidence-based review highlighted the role of outdoor recreation (e.g. walking, cycling, hiking, kayaking, canoeing) as a viable therapeutic means for people with mental illness, particularly its role in facilitating positive identity and life quality (Frances, 2006). Also, Babiss' (Babiss, 2002) ethnographic study of women with mental illness provided evidence that expressive activities such as art, music, writing and dance promote the process toward recovery, specifically as a vehicle for learning about self and for identifying feelings one cannot express verbally. Babiss indicated that ‘expression just for the sake of expression has value’ (p. 118), while emphasizing ‘the stunning importance of the human interaction and the human touch’ (p. 106). In fact, self-expressions and meaningful interpersonal interactions are two key benefits of leisure and recreation (Driver and Bruns, 1999).

Yanos and Moos' integrated model of the determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia identified leisure activities as a key dimension of social functioning (Yanos and Moos, 2007). Minato and Zemke's study with 89 community residents (aged 19–64 years) with schizophrenia in Sapporo, Japan showed that leisure can act as a stress-reliever (Minato and Zemke, 2004). As shown earlier, Davidson et al.'s (Davidson et al., 2005) international study (conducted in Italy, Norway, Sweden and the USA) found that going out and engaging in normal activities, having meaningful social roles and maintaining positive interpersonal relationships outside of the formal mental health system were found as salient themes of recovery processes.

From a positive strengths-based perspective, Carruthers and Hood (Carruthers and Hood, 2004) stressed the role of therapeutic recreation services for individuals with mental illness in facilitating resilience, thriving and life satisfaction. Pedlar et al.'s study pointed to the importance of informal recreation opportunities (e.g. informal get-together during which women inmates with mental health challenges living in a prison system spent a leisurely evening together with people from the community) rather than a conventional formalized intervention to facilitate friendship and community reintegration (Pedlar et al., 2008).

The notion of leisure as an antidote to depressive symptomotology was shown in Fullagar's (Fullagar, 2008) study with 48 Australian women with depression. This study drew on post-structural feminist theories of emotion to explore the significance of leisure within women's narratives of recovery from depression. Specifically, Fullagar found evidence that leisure: (a) helped open up positive experiences of self beyond the experiences with the medical/clinical treatment, (b) had transformative effects on gender identity (learning really ‘who I am’), (c) generated ‘hope’ that there is life beyond depression and (d) enabled the women to exercise a sense of entitlement to play and enjoy life. Importantly, recovery-oriented leisure practices involved setting new boundaries for self (e.g. personal space) and others, and elicited emotions (e.g. joy, pleasure, courage) that facilitated transformation in ways that biomedical treatments could not. Fullagar stated, ‘The recovery practices adopted by women were significant not because of the “activities” themselves but in terms of the meanings they attributed to their emerging identities. Women talked about how they engaged in leisure “for” themselves (e.g. alone or with others)’ through creative (e.g. art/craft, gardening, writing, reading, music, community theatre, self-education), actively embodied (e.g. martial arts, walking, bowls, dance, yoga, Tai Chi, swimming, meditation) and social activities (e.g. cafes, dance courses, support groups, pets, church, helping others) (p. 42).

Thus, active engagements in leisure give attention to the experiences and meanings derived from these engagements. For example, individuals with mental illness can engage in a nature walk with peers and/or friends that can provide an opportunity to gain social (e.g. companionship), emotional (e.g. positive moods) and spiritual (e.g. spiritual renewal) benefits within a natural environment beyond physical and physiological benefits of a nature walk. Empirical evidence is emerging to demonstrate that enjoyable and meaningful leisure can facilitate coping with stress and healing from trauma, and promote hope, identity (e.g. deeper understanding of self), connectedness, appreciation for life, human growth/transformation and life quality among people including persons with mental illness (e.g. Kleiber et al., 2002; Hutchinson et al., 2006, 2008; Iwasaki et al., 2006). Consistent with this evidence, Ritsner et al.'s (Ritsner et al., 2005) study with Jewish or Arab Israelis with mental illness found that leisure activities facilitated finding meaning in life, which counteracted negative states of depression and emotional distress. In addition, a recent National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI, 2004) document included an illustration about the power of enjoyable and meaningful forms of actively engaged leisure for individuals with serious mental illness.

Furthermore, from a health-promoting perspective, leisure seems to have the potential to reduce secondary health conditions (e.g. obesity) of individuals with mental illness. Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2000) defines secondary conditions as ‘medical, social, emotional, family, or community problems that a person with a primary disabling condition likely experiences.’ It has been shown that the reduction and prevention of secondary conditions are very important for persons with mental illness because of their adverse effects on health and life quality (Johnson, 1997; Perese and Perese, 2003; Merikangas and Kalaydjian, 2007). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) also recognizes the importance of managing secondary conditions of people with disabilities (WHO, 2001b). Beyond the primary disabling conditions, physical, social and environmental factors amendable through public health intervention are widely acknowledged to mediate the development of secondary conditions (Wilber et al., 2002), yet targeted lifestyle interventions for persons with mental illness are lacking (Bradshaw et al., 2005).

Within our model, and supported by recent research findings, the potential exists in utilizing leisure activities within a health promotion framework, especially physically and socially active leisure. For example, Richardson et al. (Richardson et al., 2005) implemented an 18-week lifestyle intervention program to promote physical activity and healthy eating among 39 individuals with serious mental illness and found observable weight loss (to reverse weight gain as a secondary condition) over the course of the intervention. Also, Cournos and Goldfinger (Cournos and Goldfinger, 2005) reported some success with a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention to promote walking among individuals with comorbid depression and diabetes (i.e. another secondary condition). The role of social leisure in dealing with social isolation (still as another secondary condition) has been found (e.g. Heasman and Atwal, 2004; Davidson et al., 2005; Pedlar et al., 2008), as well as the role of leisure in relapse prevention for individuals with dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance misuse (Hodgson and Lloyd, 2002).

IMPORTANCE OF CULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS

The framework includes cultural factors, health care systems and other environmental factors (e.g. family and peer support, socio-economic living conditions, neighborhood and community including parks and recreation centers, educational and employment opportunities). The interactive effects of these macro factors are assumed to influence the other components included in the framework, which is consistent with an ecological perspective of health and disability (WHO, 2001b).

Giving attention to cultural factors (e.g. race/ethnicity) is a must in the conceptualizations of leisure, active living, recovery, health promotion, life quality and health care, and its interrelationships. For example, Davidson et al.'s (Davidson et al., 2005) multinational study showed that cultural differences among individuals with mental illness from each country were noted primarily in the nature of the opportunities and supports offered rather than in the nature of the recovery processes described. Mendenhall (Mendenhall, 2008) discussed factoring culture into outcome measurement in mental health, while Warren (Warren, 2007) described cultural aspects of bipolar disorder and interpersonal meaning for clients and psychiatric nurses. Also, Ida (Ida, 2007) suggested that the critical role of culture should be acknowledged in the recovery and healing process within the context of ‘racism, sexism, colonization, homophobia, and poverty, as well as the stigma and shame associated with having a mental illness’ (p. 49). Hopper et al., 2007) conducted a cross-cultural inquiry into marital prospects after psychosis, and Rosen (Rosen, 2003) discussed how developed countries can learn from developing countries in challenging psychiatric stigma from a cross-cultural perspective. This may ‘include wider communal involvement in addressing external (psycho-sociocultural) causal or precipitating factors (e.g., losses, lack of meaningful role, spiritual crises) rather than relying on internal biological explanations and treatments’ (Rosen, 2003, p. S95). Fallot showed that spirituality is central to self-understanding and recovery experiences of many individuals with mental illness, and that recognizing the role of spirituality and religion in a particular culture is often essential to offering culturally competent services (Fallot, 2001). Also, Hwang et al. (Hwang et al., 2008) provided a conceptual paradigm for understanding how cultural factors (e.g. cultural meanings, norms, expressions) influence several core domains of mental health, including (a) the prevalence of mental illness, (b) etiology of disease, (c) phenomenology of distress, (d) diagnostic and assessment issues, (e) coping styles and help-seeking pathways and (f) treatment and intervention issues. In addition, cultural meanings of leisure engagements for racial/ethnic minorities should be acknowledged rather than imposing a dominant western idea of leisure, as emphasized in Iwasaki et al.'s (Iwasaki et al., 2007) call for a power-balance between East and West in leisure research.

Besides cultural factors, the other macro factors included in the framework represent health care systems and other environmental factors. Certainly, access to and the approaches used in mental health care systems will affect active living and recovery, including the propensity to consider leisure-based active living in overall health and life quality. Consider, for example, the personal recovery experiences described by Schiff (Schiff, 2004). As a consumer–survivor, Schiff described a recovery process that involved connections with others, the environment and the world as a key contributor to life quality. Specifically, besides her inner desire for ‘wanting to get better’ (p. 215), she talked about her own recovering experiences facilitated by her relationships with patients, medical staff and some others at university, and through reclaiming social roles with peers including helping others who have mental illness. Similarly, from a consumer perspective, Happell's (Happell, 2008) study found a supportive environment, especially connectedness with and encouragement/support from staff and peers, as a key aspect of mental health services to enhance recovery, while emphasizing that increased attention should be given to the views and opinions of consumers to develop more responsive mental health services. Also, Yanos and Moos (Yanos and Moos, 2007) identified various environmental conditions—including social climate (e.g. community stigma, economic conditions, local mental health policies), resources (e.g. social support, family resources) and stressors (e.g. family relationships, neighborhood disadvantage)—as key determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia.

Besides ensuring the quality and accessibility of resources essential for daily community living (e.g. safety/security, health care, educational and employment opportunities), creating a more active-living-friendly neighborhood and community for people with mental illness is very important. To achieve this aim, however, the maintenance of accessible/inclusive, user-friendly and pleasant parks and recreation centers that offer a diverse range of opportunities for all to enjoy quality leisure time is a top priority. Recently, both American Journal of Preventive Medicine (e.g. Godbey et al., 2005; Sallis et al., 2005) and Leisure Sciences (e.g. Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005) featured a special issue on the role of recreation and leisure in promoting active lifestyles in neighborhoods and communities (e.g. engineering a safe/secure, visually attractive and user-friendly urban-park landscape) from a transdisciplinary perspective (e.g. urban planning, landscape architecture, engineering, leisure sciences, medicine, public health).

HOLISTIC, PERSON-CENTERED, RECOVERY-ORIENTED, STRENGTHS-BASED, AND CULTURALLY SENSITIVE HEALTH AND HUMAN CARE

Another proposition implied in this framework is that persons with mental illness are in favor of and demand more holistic, person-centered, recovery-oriented, strengths-based and culturally sensitive health and human care beyond illness-focused care. Integrating humanistic leisure-based programs into health care systems would give attention to the wholeness of the individual and her/his life, in which personal and social behavior (including leisure behavior) and cultural and environmental factors influence each other. The quality and accessibility of community health care systems are an important factor for the lives of people with mental illness because the ability of those systems to adequately meet the unique needs of persons with mental illness is a critical concern for their health and life quality.

CONCLUSION

This paper has presented a heuristic conceptual framework in which the centrality of leisure engagements from a broader and more balanced experience- and meaning-oriented perspective (than simply behavioral) is viewed as a proactive, strengths-based agent and context for active living to facilitate recovery and health/life-quality enhancement. Emphasized in the framework include the functions of enjoyable and meaningful leisure not only to promote personal identity and spirituality, positive emotions, harmony and social connections, effective coping and healing functions, human development, and physical and mental health, but also the effects of these interrelated elements on promoting more enjoyable and meaningful leisure in a reciprocal way for persons with mental illness. This reciprocal transaction can, however, be both positive and negative. That is, negative discretionary time behaviors (e.g. deviant leisure; Rojek, 1999) can be detrimental to individuals just as environmental factors can support or impede meaningful leisure experiences.

Also, by adopting a holistic and ecological perspective, this framework stresses the significance of social and environmental factors including the need to transform neighborhoods and communities to be more resourceful and active-living friendly. From a global international perspective, however, the impact of cultural/cross-cultural factors should not be ignored as these are closely interconnected with neighborhood and community factors, health care systems and the other social and environmental factors (e.g. socio-economic).

Although potential contributions of leisure to active living, recovery and the promotion of health and life quality have been shown, empirical evidence is limited. Thus, we caution that: (a) key ideas presented in our heuristic conceptual framework do not necessarily imply causation with strong magnitude and duration in change through leisure, and (b) other factors may be responsible for the promotion of active living, recovery, health and life quality. Rather, the framework presented, while based on preliminary, empirical evidence, should be considered ‘heuristic’ with the intention to stimulate a more balanced, holistic/ecological and humanistic orientation for research and practice that focus on active living, recovery and the enhancement of health and life quality among culturally diverse groups of people with mental illness from both clinical and research perspectives. This paper offers some concepts that can be a guide for further thinking and inquiry about active-living and health promoting pathways through leisure from a holistic, strengths-based and humanistic perspective for culturally diverse populations with mental illness in a global context.

FUNDING

This paper is based on our project supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (Award Number R21MH086136).

REFERENCES

- Babiss F. An ethnographic study of mental health treatment and outcomes: Doing what works. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2002;18:1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bambery M., Abell S. Relocating the nexus of psychopathology and treatment: Thoughts on the contribution of Erich Fromm to contemporary psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2006;36:175–182. doi:10.1007/s10879-006-9022-0. [Google Scholar]

- Beard J. G., Ragheb M. G. Measuring leisure motivation. Journal of Leisure Research. 1983;15:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Brach J. S., Simonsick E. M., Kritchevsky S., Yaffe K., Newman A. B. The association between physical function and lifestyle activity and exercise in the health, aging and body composition study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52154.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw T., Lovel K., Harris N. Healthy living interventions and schizophrenia: a systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49:634–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03338.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. W., Brown D. R., Heath G. W., Balluz L., Giles W. H., Ford E. S., et al. Associations between physical activity dose and health-related quality of life. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36:890–896. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000126778.77049.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carless D. Phases in physical activity initiation and maintenance among men with serious mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2007;9:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers C. P., Hood C. D. The power of the positive: leisure and well-being. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2004;38:225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers C., Hood C. D. Building a life of meaning through therapeutic recreation: the leisure and well-being model, Part I. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2007;41:276–297. [Google Scholar]

- Clay S., Schell B., Corrigan P. W., Ralph R. O. On Our Own, Together: Peer Programs for People with Mental Illness. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Salzer M., Ralph R. O. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:1035–1041. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournos F., Goldfinger S. M. Frontline reports. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:353–355. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L., Borg M., Mann I. Processes of recovery in serious mental illness: findings from a multinational study. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2005;8:177–201. (Special issue: Process and contexts of recovery, Part I) doi:10.1080/15487760500339360. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L., Roe D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: one strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. Journal of Mental Health. 2007;16:459–470. doi:10.1080/09638230701482394. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon G. The Therapeutic Community: Theory, Model, and Method. New York, NY: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Driver B. L., Bruns D. H. Concepts and uses of the benefits approach to leisure. In: Jackson E. I., Burton T. L., editors. Leisure Studies: Prospects for the Twenty-first Century. State College, PA: Venture Publishing; 1999. pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- Fallot R. D. The place of spirituality and religion in mental health services. In: Lamb H. R., editor. Best of New Directions for Mental Health Services, 1979–2001. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances K. Outdoor recreation as an occupation to improve quality of life for people with enduring mental health problems. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;69:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. Escape from Freedom. New York, NY: Reinhart; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. The Sane Society. Canada: Ballantine Books; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York, NY: Harper and Row, Publishers; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar S. Leisure practices as counter-depressants: Emotion-work and emotion-play within women's recovery from depression. Leisure Sciences. 2008;30:35–52. doi:10.1080/01490400701756345. [Google Scholar]

- Godbey G., Caldwell L., Floyd M., Payne L. Contributions of leisure studies and recreation research to the active living agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.027. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg E. W., Cauley J. A., Stone K., Thompson T. J., Bauer D. C., Cummings S. R., et al. Relationship of changes in physical activity and mortality among older women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2379–2386. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2379. doi:10.1001/jama.289.18.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B. Determining the effectiveness of mental health services from a consumer perspective: Part 1: enhancing recovery. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008;17:116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00519.x. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman D., Atwal A. The active advice pilot project: leisure enhancement and social inclusion for people with severe mental health problems. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;67:511–514. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson K. A., Bialeschki M. D. Leisure and active lifestyles: research reflections. Leisure Sciences. 2005;27:355–365. doi:10.1080/01490400500225559. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson K. A., Bialeschki M. D., Shaw S. M., Freysinger V. Both Gains and Gaps: Feminist Perspectives on Women's Leisure. State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson S., Lloyd C. Leisure as a relapse prevention strategy. British Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2002;9:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K., Wanderling J., Narayanan P. To have and to hold: a cross-cultural inquiry into marital prospects after psychosis. Global Public Health. 2007;2:257–280. doi: 10.1080/17441690600855778. doi:10.1080/17441690600855778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S., Leblanc A., Booth R. More than ‘Just Having Fun’: reconsidering the role of enjoyment in therapeutic recreation practice. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2006;40:220–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S. L., Bland A. D., Kleiber D. A. Leisure and stress-coping: implications for therapeutic recreation practice. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2008;42:9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W.-C., Myers H. F., Abe-Kim J., Ting J. Y. A conceptual paradigm for understanding culture's impact on mental health: the cultural influences on mental health (CIMH) model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman S., Chisholm D., Kessler R., Patel V., Whiteford H. Mental disorders. In: Jamison D. T., Breman J. G., Measham A. R., Alleyne G., Claeson M., Evans D. B., Jha P., Mills A., Musgrove P., et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Ida D. J. Cultural competency and recovery within diverse populations. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2007;31:49–53. doi: 10.2975/31.1.2007.49.53. (Special issue: Mental health recovery and system transformation). doi:10.2975/31.1.2007.49.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y. Pathways to meaning-making through leisure in global contexts. Journal of Leisure Research. 2008;40:231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y., MacKay K., Mactavish J., Ristock J., Bartlett J. Voices from the margins: stress, active living, and leisure as a contributor to coping with stress. Leisure Sciences. 2006;28:163–180. doi:10.1080/01490400500484065. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y., Nishino H., Onda T., Bowling C. Leisure research in a global world: time to reverse the western domination in leisure research? Leisure Sciences. 2007;29:113–117. doi:10.1080/01490400600983453. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R. An existential model of group therapy for chronic mental conditions. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy. 1997;47:227–250. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1997.11490819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski A. T., Henderson K. A. Environmental correlates of physical activity: a review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leisure Sciences. 2007;29:315–354. doi:10.1080/01490400701394865. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. R., Freysinger V. J. 21st Century Leisure: Current Issues. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiber D. A., Hutchinson S. L., Williams R. Leisure as a resource in transcending negative life events: self-protection, self-restoration, and personal transformation. Leisure Sciences. 2002;24:219–236. doi:10.1080/01490400252900167. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire G. S., Mallik K. Barriers to community integration for participants in community-based psychiatric rehabilitation. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2005;19:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.04.004. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C., King R., Lampe J., McDougall S. The leisure satisfaction of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2001;25:107–113. doi: 10.1037/h0095035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C., King R., McCarthy M. The association between leisure motivation and recovery: a pilot study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2007;54:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy S., Allison D., Bray G. Obesity and Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall M. Factoring culture into outcomes measurement in mental health. In: Loue S., Sajatovic M., editors. Diversity Issues in the Diagnosis, Treatment and Research of Mood Disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., Kalaydjian A. Magnitude and impact of comorbidity of mental disorders from epidemiologic surveys. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:353–358. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281c61dc5. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281c61dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minato M., Zemke R. Time use of people with schizophrenia living in the community. Occupational Therapy International. 2004;11:177–191. doi: 10.1002/oti.205. doi:10.1002/oti.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney T. My journey of recovery. Newparadigm. 2002 (5 December) [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. Editorial. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. 2006;8:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Policy Research Institute. Arlington, VA: Author; 2004. Roadmap to Recovery and Cure: Final Report of the NAMI Policy Research Institute Task Force on Serious Mental Illness Research. [Google Scholar]

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final report. (DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832). [Google Scholar]

- Ng S. M., Chan C. L. W., Leung P. P. Y., Chan C. H. Y., Yau J. K. Y. Beyond survivorship: achieving a harmonious dynamic equilibrium using a Chinese medicine framework in health and mental health. Social Work in Mental Health. 2009;7:62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pedlar A., Yuen F., Fortune D. Incarcerated women and leisure: making good girls out of bad? Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2008;42:24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Perese E., Perese K. Health problems of women with severe mental illness. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2003;15:212–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00361.x. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn G., Degener T., Bruce A., Burke C., Castellino J., Kenna P., et al. The Current Use and Future Potential of United Nations Human Rights Instruments in the Context of Disability. New York, NY: United Nations; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon S., Healy B., Renouf N. Recovery from mental illness as an emergent concept and practice in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2007;53:108–122. doi: 10.1177/0020764006075018. doi:10.1177/0020764006075018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C. R., Avripas S. A., Neal D. L., Marcus S. M. Increasing lifestyle physical activity in patients with depression or other serious mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:379–388. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200511000-00004. doi:10.1097/00131746-200511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsner M., Kurs R., Gibel A., Ratner Y., Endicott J. Validity of an abbreviated Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q-18) for schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and mood disorders patients. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:1693–1703. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-2816-9. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-2816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojek C. Deviant leisure: the dark side of free-time activity. In: Jackson E. L., Burton T. L., editors. Leisure Studies: Prospects for the Twenty-first Century. State College, PA: Venture Publishing; 1999. pp. 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen A. What developed countries can learn from developing countries in challenging psychiatric stigma. Australasian Psychiatry. 2003;11(Suppl. 1):S89–S95. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. My road to recovery. Newparadigm. 2002 (4 December) [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J. F., Linton L., Kraft M. K. The first Active Living Research Conference: growth of a transdisciplinary field. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(Suppl. 2):93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samdahl D. M. A symbolic interactionist model of leisure: theory and empirical support. Leisure Sciences. 1988;10:27–39. doi:10.1080/01490408809512174. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N., Schulze H. Reducing the Stigma of Mental Illness: A Report from a Global Programme of the World Psychiatric Association. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff A. C. Recovery and mental illness: analysis and personal reflections. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27:212–218. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.212.218. doi:10.2975/27.2004.212.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sells D., Borg M., Marin I. Arenas of recovery for persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2006;9:3–16. (Special issue: Process and contexts of recovery, Part II). doi:10.1080/15487760500339402. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw S. M. The meaning of leisure in everyday life. Leisure Sciences. 1985;7:1–24. doi:10.1080/01490408509512105. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrick M., Brice G. H., Jr Sharing the message of hope, wellness, and recovery with consumers psychiatric hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2006;9:101–109. doi:10.1080/15487760600876196. [Google Scholar]

- Trauer T., Duckmanton R. A., Chiu E. A study of the quality of life of the severely mentally ill. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1998;44:79–91. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400201. doi:10.1177/002076409804400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor L. C., Bassett D. R., Jr How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Medicine. 2004;34:1–8. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Rockville, MD: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Transforming Mental Health Care in America, Federal Action Agenda: First Steps. Rockville, MD: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Warren B. J. Cultural aspects of bipolar disorder: interpersonal meaning for clients & psychiatric nurses. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services. 2007;45:32–37. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber N., Mitra M., Walker D. K., Allen D., Meyers A. R., Tupper P. Disability as a public health issue: findings and reflections from the Massachusetts Survey of secondary conditions. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80:393–421. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00009. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2001a. The World Health Report 2001—Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Resource Book on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yanos P. T., Moos R. H. Determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia: an integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]