Abstract

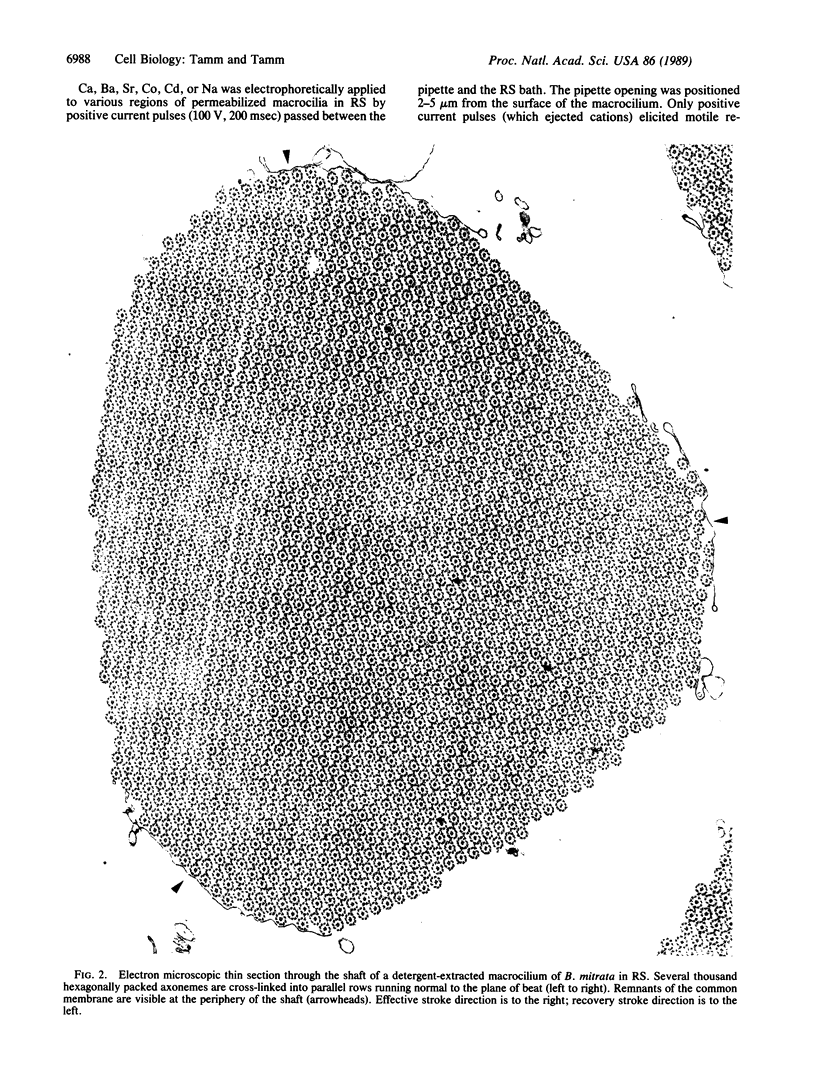

We use the Ca-dependent activation response of macrocilia of the ctenophore Beroë to map the distribution of Ca sensitivity along axonemes of detergent-extracted ATP-reactivated models. Local iontophoretic application of Ca (or Sr or Ba) to any site along the length of demembranated macrocilia in ATP-Mg solution elicits oscillatory bending. Bending responses are localized to the site of application of these cations and do not propagate. Ca sensitivity for initiating bends is, therefore, distributed along the entire length of the axonemes. Since Ca triggers ATP-dependent microtubule sliding disintegration of macrociliary axonemes, a Ca-sensitive mechanism for activating microtubule sliding extends the length of the axonemes. In contrast, local application of Ca to living dissociated macrociliary cells elicits beating only when applied to the base of the macrocilium, indicating that the effective site of Ca entry is localized to the membrane at the ciliary base. Therefore, the spatial distributions of membrane Ca permeability and axonemal Ca sensors do not coincide.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bessen M., Fay R. B., Witman G. B. Calcium control of waveform in isolated flagellar axonemes of Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1980 Aug;86(2):446–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J. Bend propagation by a sliding filament model for flagella. J Exp Biol. 1971 Oct;55(2):289–304. doi: 10.1242/jeb.55.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J. Calcium-induced asymmetrical beating of triton-demembranated sea urchin sperm flagella. J Cell Biol. 1979 Aug;82(2):401–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J., Josslin R., Bobrow L. Calcium ion regulation of flagellar beat symmetry in reactivated sea urchin spermatozoa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974 Jun 4;58(3):795–800. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(74)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J., Nagayama S. M. Modulation of the asymmetry of sea urchin sperm flagellar bending by calmodulin. J Cell Biol. 1985 Jun;100(6):1875–1883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.6.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap K. Localization of calcium channels in Paramecium caudatum. J Physiol. 1977 Sep;271(1):119–133. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons B. H., Gibbons I. R. Calcium-induced quiescence in reactivated sea urchin sperm. J Cell Biol. 1980 Jan;84(1):13–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.84.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwill M. E., McGregor J. L. Effects of calcium on flagellar movement in the trypanosome Crithidia oncopelti. J Exp Biol. 1976 Aug;65(1):229–242. doi: 10.1242/jeb.65.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyams J. S., Borisy G. G. Isolated flagellar apparatus of Chlamydomonas: characterization of forward swimming and alteration of waveform and reversal of motion by calcium ions in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1978 Oct;33:235–253. doi: 10.1242/jcs.33.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machemer H., Ogura A. Ionic conductances of membranes in ciliated and deciliated Paramecium. J Physiol. 1979 Nov;296:49–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihle N. J., Dedman J. R., Means A. R., Chafouleas J. G., Satir B. H. Presence and indirect immunofluorescent localization of calmodulin in Paramecium tetraurelia. J Cell Biol. 1981 Jun;89(3):695–699. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki-Noumura T., Kamiya R. Conformational change in the outer doublet microtubules from sea urchin sperm flagella. J Cell Biol. 1979 May;81(2):355–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.81.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss A. G., Tamm S. L. A calcium regenerative potential controlling ciliary reversal is propagated along the length of ctenophore comb plates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Sep;84(18):6476–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S., Tamm S. L. Calcium control of ciliary reversal in ionophore-treated and ATP-reactivated comb plates of ctenophores. J Cell Biol. 1985 May;100(5):1447–1454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A., Takahashi K. Artificial deciliation causes loss of calcium-dependent responses in Paramecium. Nature. 1976 Nov 11;264(5582):170–172. doi: 10.1038/264170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi K., Suzuki Y., Watanabe Y. Studies on calmodulin isolated from Tetrahymena cilia and its localization within the cilium. Exp Cell Res. 1982 Jan;137(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(82)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otter T., Satir B. H., Satir P. Trifluoperazine-induced changes in swimming behavior of paramecium: evidence for two sites of drug action. Cell Motil. 1984;4(4):249–267. doi: 10.1002/cm.970040404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed W., Satir P. Calmodulin in mussel gill epithelial cells: role in ciliary arrest. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;356:423–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb29657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingyoji C., Murakami A., Takahashi K. Local reactivation of Triton-extracted flagella by iontophoretic application of ATP. Nature. 1977 Jan 20;265(5591):269–270. doi: 10.1038/265269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S. L. Calcium activation of macrocilia in the ctenophore Beroë. J Comp Physiol A. 1988 May;163(1):23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00611993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S. L. Control of reactivation and microtubule sliding by calcium, strontium, and barium in detergent-extracted macrocilia of Beroë. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1989;12(2):104–112. doi: 10.1002/cm.970120205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S. L. Iontophoretic localization of Ca-sensitive sites controlling activation of ciliary beating in macrocilia of Beroë: the ciliary rete. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1988;11(2):126–138. doi: 10.1002/cm.970110206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S. L., Tamm S. Massive actin bundle couples macrocilia to muscles in the ctenophore Beroë. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1987;7(2):116–128. doi: 10.1002/cm.970070204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm S. L., Tamm S. Visualization of changes in ciliary tip configuration caused by sliding displacement of microtubules in macrocilia of the ctenophore Beroë. J Cell Sci. 1985 Nov;79:161–179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.79.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. F., Satir P. Calcium control of ciliary arrest in mussel gill cells. J Cell Biol. 1978 Oct;79(1):110–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.79.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]