Abstract

The role of cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in airway epithelial wound repair was investigated using normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells and a human airway epithelial cell line (Calu-3) of serous gland origin. Measurements of wound repair were performed using continuous impedance sensing to determine the time course for wound closure. Control experiments showed that the increase in impedance corresponding to cell migration into the wound was blocked by treatment with the actin polymerization inhibitor, cytochalasin D. Time lapse imaging revealed that NHBE and Calu-3 cell wound closure was dependent on cell migration, and that movement occurred as a collective sheet of cells. Selective inhibition of CFTR activity with CFTRinh-172 or short hairpin RNA silencing of CFTR expression produced a significant delay in wound repair. The CF cell line UNCCF1T also exhibited significantly slower migration than comparable normal airway epithelial cells. Inhibition of CFTR-dependent anion transport by treatment with CFTRinh-172 slowed wound closure to the same extent as silencing CFTR protein expression, indicating that ion transport by CFTR plays a critical role in migration. Moreover, morphologic analysis of migrating cells revealed that CFTR inhibition or silencing significantly reduced lamellipodia protrusion. These findings support the conclusion that CFTR participates in airway epithelial wound repair by a mechanism involving anion transport that is coupled to the regulation of lamellipodia protrusion at the leading edge of the cell.

Keywords: wound healing, cell migration, lamellipodia

the airway epithelium provides an important defense against infection by inhaled pathogens and noxious agents (46). The epithelium removes inhaled particles by mucociliary clearance and serves as a protective barrier through the formation of intercellular junctions (26, 46). Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a fatal genetic disease resulting from mutations in the gene that encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), an anion channel that participates in electrolyte and fluid transport in airways and other epithelia (2, 5, 9, 17, 49). In the airways, these mutations reduce fluid secretion, resulting in viscous mucus accumulation, impaired mucociliary clearance, and microorganism colonization of the lung (17, 31, 40). The ensuing chronic and recurrent inflammatory responses to colonization lead to cycles of epithelial damage and wound repair (4, 39, 53). Recently, a humanized xenograft mouse model of CF was used to demonstrate that airway epithelial regeneration is impaired in bronchial epithelial cells even in the absence of airway infection (19), suggesting that CFTR plays a role in airway regeneration.

Previous investigations have shown that the process of epithelial wound repair is initiated by migration of cells at the leading edge of the wound (10, 38). At this site, cells adopt a polarized migration phenotype and cycle through extensions of actin-based membrane protrusions called lamellipodia, and retractions of the cell's trailing edge (25, 27) until wound closure is complete (51). In bronchi, cell proliferation is then essential to reestablish a pseudostratified epithelium, which is composed of basal, ciliated, and mucus-secreting (goblet) epithelial cells (6, 21, 35). Among these cell types, both basal and secretory epithelial cells have proliferative capacity (18, 53), and a stem cell population has been identified in airway submucosal glands (28). Other progenitor-like cell types are important for renewal of the distal airways including Clara cell protein 10 (CC10)-positive Clara cells and surfactant protein A (SP-A)-expressing type II pneumocytes in the bronchioles and alveoli, respectively (23, 50). In the bronchi, basal cells are thought to be the major progenitor cell population for restoration of the epithelium following injury (26). These cells are capable of reconstituting a pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium in air-liquid interface cultures and xenografts (18). Additionally, CF airway epithelia were shown to have a higher index of proliferating cells compared with healthy epithelia, and these proliferative cells expressed the basal cell markers cytokeratin 5 and 14, and the proliferative marker epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (53). Basal cells therefore are an important cell population for epithelial renewal and repair in diseases such as CF. Submucosal gland epithelial cells are also relevant in CF since the disease is characterized by severe airway submucosal gland hypertrophy and hyperplasia (14). Airway submucosal glands are thought to provide the molecular signals required to maintain and mobilize progenitor cells during airway turnover and in response to injury (28). Characterizing the role of basal and submucosal gland epithelial cells in airway wound repair is necessary for understanding the airway remodeling that occurs in CF and other chronic inflammatory diseases of the airways.

In this study, the contribution of CFTR to airway epithelial wound closure was investigated. Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells expressing basal cell markers, and an airway epithelial cell line (Calu-3) of serous gland origin were used for these experiments. Additionally, an immortalized human bronchial epithelial cell line isolated from a CF patient (homozygous ΔF508), UNCCF1T (16), was also used. Continuous impedance sensing (CIS) combined with phase-contrast imaging was employed to measure the time required for complete wound closure. To establish whether CFTR plays a role in wound closure, selective pharmacological inhibition of channel activity was assessed, as was silencing CFTR protein expression, and the wound closure rate of CF cells was compared with normal airway epithelial cells. Additionally, the effect of CFTR inhibition and silencing on lamellipodia protrusion was analyzed by fluorescent imaging of cells during wound repair. The results demonstrated that inhibition of CFTR transport activity produced significant delays in wound closure that correlated with a reduction in lamellipodia surface area.

METHODS

Materials

Calu-3 cell culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, trypsin, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from GIBCO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM) was purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ). Trypan blue, EIPA, and cytochalasin D were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). CFTRinh-172 was provided by Dr. Robert Bridges (Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, IL). Purecol bovine collagen solution was purchased from Advanced Biomatrix (San Diego, CA). Superscript II reverse transcriptase, Texas-Red phalloidin, DAPI, and SlowFade Gold antifade reagent were purchased from Invitrogen. SYBR green master mix for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Turbo DNA-free kits for DNase treatment of RNA were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). Tris·HCl gels for Western blots were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and anti-CFTR antibody were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). All secondary antibodies and anti-β-tubulin antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The Western blot protein marker was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent was purchased from GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK). Paraformaldehyde (16%) was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA).

Cell Culture

The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, Calu-3, was maintained in MEM media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBE) purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ) were passage extended by transfection with the catalytic subunit of human telomerase as previously described (32, 33). NHBE cells were maintained in complete bronchial epithelial growth media (bronchial epithelial basal medium + BEGM Bullet Kit). UNCCF1T cells were provided by Dr. Scott Randell (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) and were maintained in complete bronchial epithelial growth media. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

CFTR shRNA Silencing

CFTR was silenced in Calu-3 cells using the Sleeping Beauty transposon vectors pT2/si-PuroV2 for short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression as previously described (32, 33). Positive transfectancts were selected using puromycin (4 μg/ml). As a control, an altered shRNA (ALTR) that lacked target specificity was expressed in Calu-3 cells.

Measurement of CFTR Expression Levels

Silencing of CFTR was verified in CFTR-specific shRNA (shCFTR) vs. ALTR and wild-type Calu-3 cells by measuring CFTR mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. The expression of airway epithelial cell markers was also determined by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted using cell lysis buffer RLT (Qiagen), followed by mRNA enrichment using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Messenger RNA was then subjected to DNase treatment followed by reverse transcription (RT) reactions to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) using 0.5 μg DNase-treated mRNA. RT reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative PCR reactions contained 1 μl of the RT reaction, 12.5 μl 2× SYBR green master mix, 0.375 μl passive reference dye (1:500), and 0.325 μl water in a 25-μl reaction. Reactions were run on a Mx3005P real-time PCR machine (Stratagene), with the following thermal profile: single thermal cycle of 10 min at 95°C; 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s, 68°C for 1 min, and a final cycle to generate the dissociation curve of 95°C for 1 min followed by 30 s at 59°C and 30 s at 95°C.

The level of CFTR expression was calculated from fold change measured by qRT-PCR using the equation: fold change = 2−ΔΔCT and represents separate qRT-PCR reactions from two separate cell isolations. The average expression levels of the airway epithelial markers were determined by averaging CT values of qRT-PCR reactions of two unique primer sets using cDNA originating from a single 100-mm plate each of Calu-3 and NHBE cells. Primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR: sequences of human primer sets used for qRT-PCR in Calu-3, NHBE, and UNCCF1T cells

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| CFTR F | AGCATTTGCTGATTGCACAG |

| CFTR R | ACTGCCGCACTTTGTTCTCT |

| GAPDH F | GGACTCATGACCACAGTCCAT |

| GAPDH R | CAGGGATGATGTTCTGGAGAG |

| CD151 F no. 1 | TGGAGACCTTCATCCAGGAG |

| CD151 R no. 1/2 | GTACAGGCAGCACGTGAAGA |

| CD151 F no. 2 | GAGACCTTCATCCAGGAGCA |

| EGFR F no. 1/2 | AACTGTGAGGTGGTCCTTGG |

| EGFR R no. 1 | GTTGAGGGCAATGAGGACAT |

| EGFR R no. 2 | GGAATTCGCTCCACTGTGTT |

| Cytokeratin 5 F no. 1/2 | CAAGCGTACCACTGCTGAGA |

| Cytokeratin 5 R no. 1 | CATCAGTGCATCAACCTTGG |

| Cytokeratin 5 R no. 2 | CATCCATCAGTGCATCAACC |

qRT-PCR, quantitative RT-PCR; NHBE, normal human bronchial epithelial; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Measurement of CFTR Function

Transepithelial resistance of Calu-3 cell monolayers was measured using an EVOM epithelial voltohmmeter coupled to Ag/AgCl “chopstick” electrodes [World Precision Instruments, (WPI) New Haven, CT]. Measurements of CFTR activity were performed using monolayers (∼1,000 Ω·cm2) mounted in Ussing chambers and bathed on both sides with standard saline solution containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 6 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 NaHCO3, 0.3 NaH2PO4, and 1.3 Na2HPO4, pH 7.4, maintained at 37°C and bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. CFTR was activated using 2.5 μM 8-cpt-cAMP. Data were digitized, stored, and analyzed using Axoscope software (Axon Instruments).

Cell Migration

Electric cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) was used to measure airway epithelial cell migration. Epithelial cells were grown on 8W1E ECIS arrays (Applied Biophysics) in growth media with serum until fully confluent, after which the media were replaced with serum-free media for 48 h. To induce wound repair, a uniform circular lesion (250 μm) was produced by lethal electroporation (6 V, 30 kHz, 60 s) of cells in contact with the electrode. Cells were then washed with PBS using a 23-gauge needle to dislodge any remaining electroporated cells from the electrode, and the treatment media were added. Alternating current (∼1 μA, 15 kHz) was then continuously applied to the electrode to measure impedance (Z) and track wound repair over a period of 24 h. The time required for complete wound closure was determined from the impedance time courses. At wound closure the impedance plateaus, and the time at which this plateau occurred in each well of ECIS arrays under each treatment condition was reported as the time to wound closure. Experiments were performed in serum-free, HCO3−-buffered media in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Time Lapse Video Imaging of Wound Closure

Calu-3 cells were grown on an ECIS array to confluence, serum starved for 48 h, wounded by electroporation, washed with PBS to remove electroporated cells, and mounted into the stage incubator. The stage incubator was temperature (37°C) and humidity controlled, and gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2. Brightfield phase-contrast images of closing wounds were captured with a ×20 objective once every minute until wound closure was complete, using a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope equipped with a Diagnostic Instruments digital camera. Images were collected and composed into a time lapse image series using Spot Advanced software (version 4.6).

Fluorescent Microscopy

Producing wounds in epithelial cells on chamber slides.

Calu-3 cells were cultured on glass chamber slides coated with Purecol bovine collagen solution (3 mg/ml) diluted 1:75 in sterile water. NHBE cells were plated directly onto glass chamber slides. Epithelial cells were maintained on chamber slides in standard growth media until confluent, then changed to serum-free conditions for 48 h. Circular wounds were produced by pressing the ∼300 μm blunt end of a surgical microforceps against the glass surface. Approximately 10 wounds were made in each well in this manner. Cells were washed with PBS, and treatment media were added for 45 min or 1 h. Cells were then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde.

Visualization of lamellipodia.

Fixed cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 20 min then stained with Texas-Red phalloidin (5 U/ml) at room temperature for 20 min. Cells used for confocal microscopy were additionally stained with DAPI (300 nM) for 2 min. SlowFade antifade reagent (2 drops/chamber) was added to stained chamber slides before imaging. Images were taken of cells at wound leading edges at ×40 (1,024 × 1,024 pixel area) using either a Nikon C1si laser-scanning confocal microscope, and compiled into Z stacks using C1si software (Nikon), or a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope equipped with a Diagnostic Instruments monochrome digital camera. The area (in pixels) of each lamellipodium per cell was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and the average lamellipodium area/cell in each captured image was used for statistical analysis.

Cell Viability

The viability of CFTRinh-172 and cytochalasin D-treated cells was determined by Trypan blue exclusion. Each well of cells was individually trypsinized from ECIS arrays, pelleted, and resuspended in 500 μl PBS, and 100 μl of 0.4% Trypan blue solution was added. Suspended cells were incubated with Trypan blue at room temperature for 5 min, and the number of live (Trypan blue excluding) and dead (blue) cells was counted using a hemocytometer.

Cell Proliferation

The number of proliferating cells was compared under conditions of serum depravation (48 h) compared with growth media in Calu-3 and NHBE cells, and between ALTR Calu-3 cells and shCFTR Calu-3 cells. Cell cycle arrest was induced in controls by treatment with hydroxyurea (500 μM) for 24 h in serum-free media. Cells were incubated with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) during the final 6 h of treatment and the number of proliferating cells was determined using the BrdU Cell Proliferation assay (EMD Biosciences; La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis of CFTR Protein Expression

Expression of CFTR protein in wild-type, ALTR, and shCFTR-expressing Calu-3 cells was analyzed by Western blot. Isolated protein cell lysate (80 μg) was loaded in a 7.5% Tris·HCl gel. The protein was transferred to an Immobilon PVDF membrane, blocked with 3% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with monoclonal CFTR antibody 1:377 (clone M3A7). The membrane was then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) 1:3,000, followed by incubation for 1 min with ECL Western blot detection reagent. The blot was then used to expose X-ray film. The blot was then stripped for 40 min with buffer containing 25 mM glycine, pH 2.0, and 1% SDS and reblocked with 5% milk in TBS with Tween (0.05%) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal β-tubulin antibody 1:1,000 overnight at 4°C. The blot was incubated with secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP 1:3,000 at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated with ECL Western blot detection reagent as above and used to expose X-ray film. Protein marker used was ColorPlus prestained broad range (7–175 kDa), 10 μl/lane.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined for different mean values by two-tailed unpaired t-tests (when single comparisons were made) or one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post tests for multiple comparisons between treatments. Welch's correction was applied to t-tests when comparisons were made between two data sets with significantly different variances. Significance was accepted for all P < 0.05. A minimum of three independent experiments were performed, with a total number of replicates of six or greater per treatment condition for each experiment. All bar graphs display standard errors of the mean, and significance is indicated in figures with asterisks.

RESULTS

Inhibition of CFTR Reduces the Rate of Airway Epithelial Cell Wound Closure

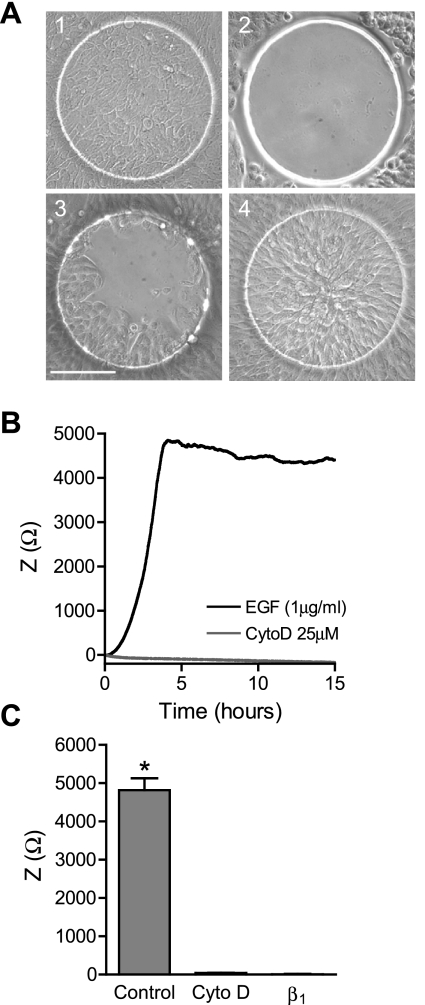

Airway epithelial wound closure was measured by CIS following wounding by electroporation. During wound repair, airway epithelial cells were visualized on the array to correlate the degree of wound closure with the change in impedance (Fig. 1A). The wound closure rate for Calu-3 cells was measured in response to treatment with EGF, which has previously been shown to enhance cell migration (25) (Fig. 1B). Following wounding, Calu-3 cells accomplished complete wound closure within 4 h (Fig. 1, A and B). Treatment with the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D (25 μM) abolished Calu-3 cell wound repair (Fig. 1B). Calu-3 cells treated with cytochalasin D were 81.8 ± 3.3% viable for the full 24 h of treatment, indicating that inhibition of wound repair was not due to cell death. Calu-3 cell suspensions were also treated with β1-integrin blocking antibody (5 μg/ml), which inhibited adhesion. No significant change in impedance was measured by CIS in Calu-3 cells treated with this antibody during adhesion (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that changes in impedance require an adhesive interaction between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) present on the electrode surface.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of wound closure by continuous impedance sensing (CIS). CIS was used to measure wound closure in Calu-3 cells. A: images of electrodes: 1) before wounding, 2) immediately after wounding, 3) 1 h after wounding, and 4) at wound closure (3 h). Scale bar = 100 μm. B: averaged impedance (Z) time course during wound closure from a representative experiment of Calu-3 cells treated with 1 μg/ml EGF and vehicle (DMSO; black) or 25 μM cytochalasin D (CtyoD; gray). C: Calu-3 cell impedance at the time of wound closure with control media (1 μg/ml EGF) and at the same time point with cytochalasin D treatment, and final impedance after 24-h treatment of Calu-3 cell suspension with anti-β1-integrin (β1). *Significant differences between means.

Wound closure was measured under serum-free conditions, although only a small reduction (<20%) of NHBE cell proliferation was measured under these conditions compared with growth media. Calu-3 cell proliferation was not significantly reduced under serum-free conditions, in contrast to treatment with the cell cycle inhibitor hydroxyurea, which produced a >40% reduction of NHBE cell proliferation and >60% reduction of Calu-3 cell proliferation. However, the time required for wound closure is much shorter than reported doubling times of human bronchial epithelial cells (50), indicating that cell migration rather than proliferation is the major component of wound repair under these experimental conditions.

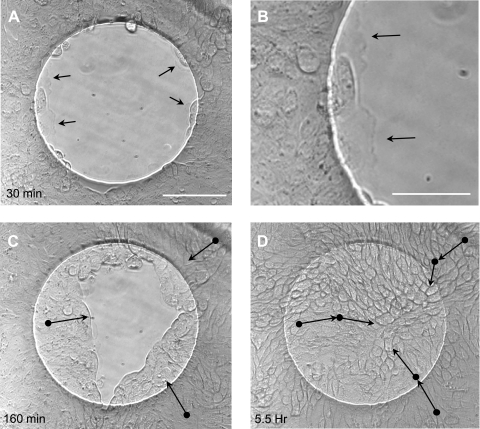

To clarify the mechanism of wound closure, time lapse video imaging was performed during wound closure on ECIS arrays under control conditions (serum-free media + 1 μg/ml EGF). Calu-3 cells, propelled by protrusions of their lamellipodia, could be clearly seen to move from the periphery of the wound into the wounded space (Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Material is available online at the Journal website). Cell division was not observed during wound closure. Interestingly, migrating cells moved together collectively, without opening visible spaces between cells or detaching visibly from each other. Lamellipodia were also clearly visible protruding from the leading edge cells throughout the wound closure process (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). Nearly all the cells in the captured image region (∼150% larger than wound area) participated in migration and could be seen moving together to facilitate wound closure (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Time lapse images of wound closure in Calu-3 cells. Brightfield phase-contrast images are shown from a time lapse wound closure sequence of Calu-3 cells with control media (serum free + 1 μg/ml EGF). A: image captured 30 min after wounding. Scale bar, 100 μm. B: enlarged image of lamellipodia in A at the leading edge of the wound 30 min after wounding. Scale bar, 50 μm. Arrows in A and B indicate lamellipodia. C: image captured 160 min after wounding. D: image captured 5.5 h after wounding. Movement of individual cells shown in C and D with arrows indicating approximate direction of movement, and starting point of movement indicated by solid black circles. Cells were identified on the basis of their morphology and tracked at 1-min intervals until reaching the positions indicated in the figure.

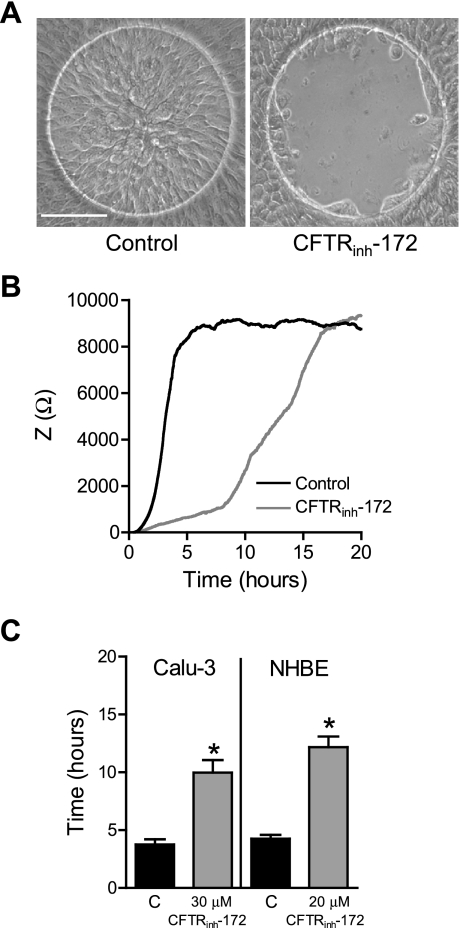

The role of CFTR in airway epithelial cell wound closure was then assessed by CIS using the selective CFTR inhibitor, CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 3). NHBE cells were found to be more sensitive to the CFTRinh-172 vehicle, DMSO, and so a lower concentration was used for these cells than for the Calu-3 cells. Inhibition of CFTR channel activity with CFTRinh-172 following wounding delayed wound closure of both Calu-3 and NHBE cells (Fig. 3, A–C). Time to wound closure increased significantly for CFTRinh-172 (30 μM)-treated Calu-3 cells by 6.2 h, and for CFTRinh-172 (20 μM)-treated NHBE cells by 10.0 h (Fig. 3, B and C). The effect of CFTR inhibition on wound closure was also verified visually by imaging electrodes over time following wounding. Very little wound closure had occurred during treatment with CFTRinh-172 for either NHBE (data not shown) or Calu-3 cells (Fig. 3A) at the time point at which wound closure was complete in control-treated cells. Assessment of NHBE and Calu-3 cell viability with CFTRinh-172 treatment revealed no significant change compared with control (DMSO vehicle) after 24 h (% viable cells: Calu-3: control 99.4 ± 0.6% vs. CFTRinh-172 96.2 ± 1.7%; NHBE: control 94.0 ± 2.5 vs. CFTRinh-172 92.0 ± 2.3%). Therefore, the effect of CFTR inhibition on wound closure was not due to nonspecific toxic effects. Rather, these data indicate that CFTR channel activity plays a role in the process of wound healing in airway epithelial cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of CFTR inhibition on wound closure. A: images of vehicle (DMSO)-treated Calu-3 cells after complete wound closure (3 h; left) or CFTRinh-172-treated cells at the same time point (3 h; right). Scale bar, 100 μm. B: averaged impedance time course during wound closure from a representative experiment of normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells treated with vehicle (DMSO; black line) or CFTRinh-172 (gray line). C: time required for complete wound closure in Calu-3 and NHBE cells treated with vehicle (black bars) or CFTRinh-172 (gray bars). *Significant differences between means.

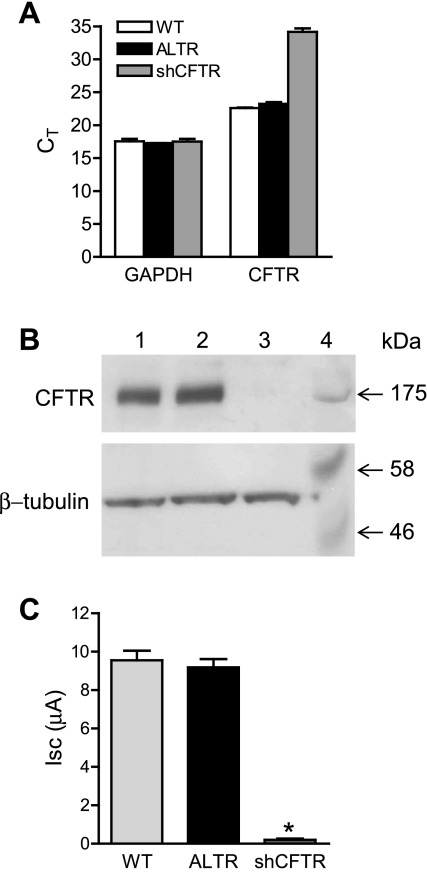

To further characterize the role of CFTR in wound repair, CFTR was silenced in Calu-3 cells by constitutive expression of CFTR-specific shRNA (shCFTR). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that CFTR transcript levels were decreased by >99% in Calu-3 cells expressing CFTR-specific shRNA (Fig. 4A). Expression of a control shRNA that lacked target specificity, shALTR (ALTR), did not significantly affect CFTR transcript levels compared with wild-type Calu-3 cells (Fig. 4A). CFTR protein expression was not detectable by Western blot in shCFTR-expressing Calu-3 cells, whereas abundant CFTR protein was found in ALTR-expressing and wild-type cells (Fig. 4B). Short circuit current (Isc) measurements of Calu-3 cell monolayers expressing CFTR-specific shRNA revealed a >97% decrease in 8-cpt-cAMP-stimulated Isc compared with wild-type and ALTR-expressing Calu-3 cells (Fig. 4C). This result indicated that very little functional CFTR was present following expression of CFTR-specific shRNA.

Fig. 4.

Silencing CFTR in Calu-3 cells. A: cycle threshold (CT) values from quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of CFTR and GAPDH expression in wild-type Calu-3 cells (WT, white bar), control altered short hairpin (sh)RNA (ALTR)-expressing Calu-3 cells (black bars), and CFTR-specific shRNA (shCFTR)-expressing Calu-3 cells (gray bars). B: Western blot of CFTR (top) and β-tubulin (bottom) protein levels in ALTR-expressing Calu-3 cells (lane 1), wild-type Calu-3 cells (lane 2), shCFTR-expressing Calu-3 cells (lane 3), and molecular mass markers in kDa (lane 4). C: measurements of 8-cpt-cAMP (2.5 μM)-stimulated short-circuit current (Isc) in monolayers of wild-type Calu-3 cells (light gray bar), ALTR Calu-3 cells (black bar), and CFTR-silenced Calu-3 cells (dark gray bar). *Significant difference between means.

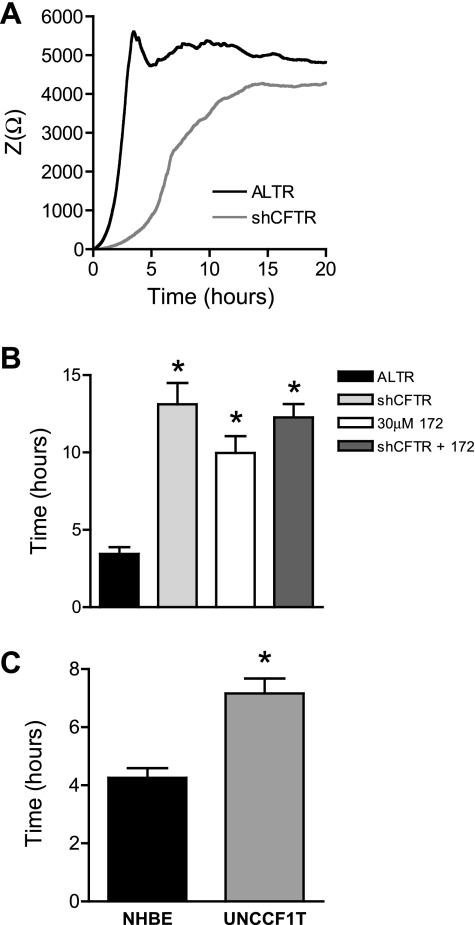

Loss of CFTR expression in Calu-3 cells delayed wound closure by 9.7 h compared with wild-type and ALTR-expressing controls (Fig. 5, A and B), equivalent to the effect on wound closure measured with inhibition of CFTR activity with CFTRinh-172. The magnitude of the delay of wound closure was not significantly different in Calu-3 cells whether CFTR was silenced by shRNA expression, or CFTR activity was inhibited by treatment with CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 5B). Moreover, treatment of CFTR-silenced Calu-3 cells with CFTRinh-172 did not further reduce the rate of wound closure (Fig. 5B), indicating that the compound was selective for CFTR at the concentration used. Finally, the relative number of proliferating shCFTR-expressing Calu-3 cells was not reduced compared with ALTR-expressing cells, but rather was significantly higher by 1.3-fold, indicating that a difference in cell proliferation was not the basis for the delay of wound closure.

Fig. 5.

Wound closure of CFTR-silenced cells. CIS was used to measure wound closure in CFTR-silenced (shCFTR) and control shRNA-expressing (ALTR) Calu-3 cells. A: averaged impedance time course during wound closure from a representative experiment of shCFTR (gray line) and ALTR (black line) Calu-3 cells. B: time required for complete wound closure of ALTR-expressing Calu-3 cells (black bar), shCFTR-expressing cells (light gray bar), wild-type Calu-3 cells treated with CFTRinh-172 (white bar), and shCFTR-expressing cells treated with 30 μM CFTRinh-172 (dark gray bar). C: time required for wound closure of NHBE cells (black bar) and UNCCF1T cells (gray bar). *Significant differences between means.

Migration Rate of CF Airway Epithelial Cells

To test whether expression of the ΔF508 CFTR mutation slowed airway epithelial cell migration, the migration rate of a human CF patient-derived bronchial epithelial cell line (UNCCF1T) was measured by CIS. These cells were isolated from the lungs of homozygous ΔF508 CFTR CF patients at the time of lung transplant and immortalized by expression of Bmi-1 and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) (16). The migration rate of UNCCF1T cells was compared with hTERT-expressing NHBE cells. Although these cells have been immortalized with different vectors and exhibited different steady-state impedances, the mRNA expression of two basal cell type markers, cytokeratin 5 and tetraspanin CD151, as well as the proliferative cell marker epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was similar (Fig. S2, A–C), and the media conditions were identical between the two cell lines. A comparison of the migration rate of UNCCF1T to NHBE cells revealed a 1.7-fold slower migration of UNCCF1T cells, and an increase in time required for wound closure of 2.9 ± 0.6 h (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that expression of ΔF508 CFTR slows migration.

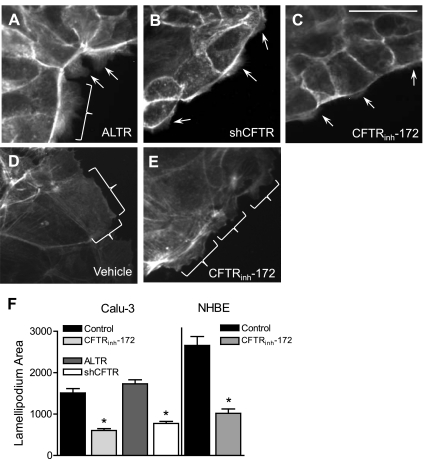

Inhibition of CFTR Reduces Lamellipodia Protrusion

To assess the possibility that inhibition of CFTR affects airway epithelial cell migration, lamellipodia area protruding at the leading edge of wounds was measured. Confluent NHBE and Calu-3 cells were wounded and then treated with control media or CFTRinh-172 as described for the CIS migration experiments. Maximum lamellipodia protrusion was observed and measured 1 h after wounding Calu-3 cells, and 45 min after wounding NHBE cells under control treatment conditions (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3). The area of the lamellipodia was reduced by 2.5- and 2.6-fold when CFTR was inhibited in Calu-3 (Fig. 6, C and F) or NHBE cells, respectively (Fig. 6, D–F). The area of lamellipodia of CFTR-silenced Calu-3 cells was also reduced by 2.2-fold compared with ALTR control Calu-3 cells (Fig. 6, A, B, and F). These data indicate that inhibition of CFTR activity reduces lamellipodia protrusion in Calu-3 and NHBE airway epithelial cells during wound closure.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CFTR inhibition on lamellipodia area. Lamellipodia areas were measured at the time of maximum protrusion following wounding of Calu-3 and NHBE cells. A–E: images (taken at ×40 magnification) of Calu-3 cells (A–C) stained with fluorescent phalloidin 1 h after wounding; protruding lamellipodia indicated by brackets and arrows. Shown are ALTR-expressing Calu-3 cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) (A); shCFTR-expressing Calu-3 cells (B); and Calu-3 cells treated with 30 μM CFTRinh-172 (C); scale bar, 20 μm. D and E: NHBE cells stained with fluorescent phalloidin 45 min after wounding; protruding lamellipodia indicated by brackets. Shown are NHBE cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) (D) and NHBE cells treated with 20 μM CFTRinh-172 (E). F: average lamellipodium area (pixels) per cell of Calu-3 and NHBE cells described in A–E. *Significant differences between means.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the role of CFTR in airway epithelial cell migration was assessed by measuring changes in wound closure rates following pharmacologic inhibition of CFTR anion transport, silencing of CFTR protein expression, and in cells expressing ΔF508 CFTR. The effect of CFTR inhibition and silencing on lamellipodia protrusion was also measured to determine whether anion transport by CFTR contributes to the protrusion of this structure in migrating cells.

Abundant expression of the basal cell markers CD151 and cytokeratin 5 in NHBE and UNCCF1T cells suggests that these cells exhibit basal cell-like properties. Expression of the proliferative cell marker EGFR in NHBE and UNCCF1T cells is consistent with this phenotype. CFTR expression in NHBE and Calu-3 cells was found to be similar to native airway epithelia where the level of expression in surface cells is typically lower than in submucosal gland epithelial cells (11, 52). Calu-3 cells are derived from airway submucosal glands (45), whereas NHBE cells are nonglandular bronchial epithelial cells. Thus, differences in CFTR expression between these cells presumably reflect their origin. The abundant CFTR expression in Calu-3 cells has made them a well-characterized model cell for the study of CFTR function (20). Additionally, our observation that NHBE cells express basal cell markers suggests that they represent a useful in vitro model cell system for investigating the role of CFTR in bronchial epithelial wound repair.

In this study, a novel approach (CIS) was used to quantify both the magnitude and the time course of epithelial restitution by measuring increases in impedance due to wound closure. Our previous studies using this approach with eosinophils (3) and with airway epithelial cells showed that the increase in impedance results from specific integrin-mediated interactions between cells and the ECM attached to the electrode. Our studies demonstrated that treatment with β-integrin-blocking antibodies that prevent adhesion also abolishes impedance. Imaging cells during wound closure confirmed that impedance increased as cells closed wounds over the electrode surface, and that complete wound closure coincided with the plateau in impedance.

Previous studies of migration of epithelial monolayers revealed that cell-cell contacts are maintained and that cells migrate as a collective unit to close wounds (13, 25, 54). Video imaging of Calu-3 cells confirmed this in airway epithelial cells. Video imaging of Calu-3 monolayers also revealed that wound closure is a collective process involving many more cells than those immediately surrounding the wound.

CIS experiments demonstrated that the rate of human airway epithelial cell wound closure was reduced when CFTR was inhibited or silenced. The magnitude of this delay was not significantly different whether CFTR was blocked by CFTRinh-172 or silenced by constitutive expression of shRNA. Although CFTR was not specifically activated in these experiments by addition of agonists that stimulate adenylyl cyclase, previous studies have shown that basal release of prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2) increases cAMP in these cells. This was confirmed in Ussing chamber experiments showing that basal CFTR-dependent anion currents were blocked by treatment with the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (33). Therefore it is likely that basal CFTR activity in these cells was dependent on autocrine mediators that would include prostaglandins and perhaps purinoceptor agonists such as ATP and adenosine.

Additionally, the migration rate of the CF cell line UNCCF1T was found to be significantly slower than the comparable normal airway epithelial cell line NHBE. This suggested that expression of ΔF508 CFTR slows cell migration of airway epithelial cells. These findings support the conclusion that the role of CFTR in wound repair was dependent on its transport activity, rather than other functions of the CFTR protein. CFTR transports both Cl− and HCO3− (34, 37); thus the data suggest that transport of one or both of these ions appears to underlie the mechanism by which CFTR contributes to wound repair.

Analysis of the time course for NHBE and Calu-3 cell wound repair measured by CIS revealed that full restitution occurred rapidly, with an average time of 4.5 h, much shorter than reported doubling times of bronchial epithelial cells of 50–80 h (50). Thus it is likely that proliferation was probably not a significant factor in wound closure since it occurs too slowly to account for the rapid wound closure observed in these experiments and because cell proliferation was not reduced in CFTR-silenced cells despite the delay in wound closure. Time lapse video of Calu-3 wound closure clearly demonstrated that wound closure occurs predominantly by migration. These data indicate that the role of CFTR in wound closure is associated with cell migration.

To investigate the contribution of CFTR to the process of migration, an assay was developed to assess morphometric changes in lamellipodia protrusion during wound repair. Lamellipodia are composed of actin filaments aligned in an array perpendicular to the cell membrane (27). In this assay, migrating cells were labeled with phalloidin, a fluorescent actin stain that allowed for visualization and measurements of lamellipodia area. Our data showed that the lamellipodia area of migrating airway epithelial cells was significantly reduced when CFTR was silenced or its transport activity was inhibited. These data indicated that the onset of lamellipodia protrusion was delayed in the absence of CFTR activity. This result implicates CFTR in the process of lamellipodia protrusion during cell migration.

Ion transport by CFTR may have several roles in cell migration and lamellipodia protrusion. For example, activation of a Cl− conductance may be important for controlling cell volume at the trailing edge of migrating cells as a mechanism to facilitate retraction (41). Several reports in multiple cell types (22, 43, 44) have shown that inhibition of certain K+ channel subtypes slows the rate of cell migration (42). K+ channels participate in regulation of cell volume by providing a pathway for K+ exit at the rear of the cell, creating a driving force for water efflux (41, 42). The importance of K+ channels in migration presumably necessitates Cl− channel activation as a means of sustaining K+ transport and to provide additional solute efflux to enhance the osmotic driving force. However, little is known about the identity of Cl− channels involved in the process. Thus, CFTR may potentially contribute to volume decrease that assists cell migration in this manner. However, the results of the present study indicate that CFTR is involved in lamellipodia protrusion; therefore CFTR may contribute to this process through a direct role in volume uptake. It is possible that lateral polarization required for cells to migrate also alters the membrane potential, and membrane depolarization has been reported during wound healing of corneal epithelial cells (8). Depolarization of the cell may be sufficient to promote Cl− uptake through CFTR to produce swelling required for lamellipodia protrusion (24).

Another possible role for CFTR could involve regulation of intracellular pH where HCO3− transport out of the cell may be necessary to sustain activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE1). NHE1 is an important regulator of cell migration in many cell types (1, 7, 36, 47) where it participates in establishing migratory polarity (12) and promoting lamellipodia protrusion (15, 30). NHE1 activity is strongly activated by intracellular acidification (36) so that efflux of HCO3− by CFTR, either directly or in cooperation with Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, may sustain NHE1 activity during migration by limiting intracellular alkalinization. This could facilitate lamellipodia protrusion and may be one mechanism to explain the delayed protrusion and reduced lamellipodia area observed following inhibition or silencing of CFTR.

CFTR may also influence cell migration by affecting cell adhesion. Migrating cells must be able to exert traction by adhesion of lamellipodia at the leading edge of the cell, while at the same time the cell body must detach from the ECM so that movement can occur (29). Thus, tight regulation of adhesion assembly and disassembly makes cell migration possible (38). Extracellular pH (pHe) appears central to regulation of cell adhesion during migration (48). Alkaline pHe promotes decreased adhesion, while acidic pHe promotes the formation of strong adhesions (47). Some migrating cells produce a pH gradient that is acidic at the leading edge of lamellipodia, favoring adhesion, and alkaline at the rear of the cell, promoting release and retraction (48). CFTR may affect this process by mediating HCO3− efflux and regulating buffering capacity at the membrane-ECM interface, either alone or through functional interactions with Cl−/HCO3− exchangers. Inhibition of CFTR activity may be relevant at the leading edge of the cell in that reduced buffering capacity could increase adherence, making lamellipodia protrusion along the surface of the ECM more difficult.

In conclusion, loss of CFTR activity either through pharmacologic inhibition or reduced protein expression impaired wound closure in human bronchial epithelial cells with basal cell characteristics and in Calu-3 cells. The data indicated that wound closure occurred predominantly by cell migration and that CFTR activity was necessary for sustaining a maximum rate of migration. The results also revealed that the loss of CFTR transport activity reduced lamellipodia area, demonstrating that CFTR transport is involved in lamellipodia protrusion and that this may explain the slower rate of migration when CFTR is inhibited. Ultimately, these findings suggest the possibility that in CF patients, loss of CFTR function slows the rate of wound closure, thus increasing chances for opportunistic infection resulting from diminished mucosal barrier function. Presently, the consequences of impaired migration on chronic airway inflammation in CF patients are uncertain, thus further studies are needed to evaluate potential contributions to CF lung disease.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-074010 and HL-095811 (to S. M. O'Grady).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert Bridges, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Rosalind Franklin University, for the generous gift of CFTRinh-172. We also thank Dr. Scott Randell from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, for the UNCCF1T cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander RT, Grinstein S. Na+/H+ exchangers and the regulation of volume. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 187: 159–167, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Souza DW, Paul S, Mulligan RC, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science 253: 202–205, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bankers-Fulbright JL, Bartemes KR, Kephart GM, Kita H, O'Grady SM. Beta2-integrin-mediated adhesion and intracellular Ca2+ release in human eosinophils. J Membr Biol 228: 99–109, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilton D. What did we learn from the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference? J R Soc Med 101, Suppl 1: S6–S9, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucher RC. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J 23: 146–158, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breeze RG, Wheeldon EB. The cells of the pulmonary airways. Am Rev Respir Dis 116: 705–777, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardone RA, Bellizzi A, Busco G, Weinman EJ, Dell'Aquila ME, Casavola V, Azzariti A, Mangia A, Paradiso A, Reshkin SJ. The NHERF1 PDZ2 domain regulates PKA-RhoA-p38-mediated NHE1 activation and invasion in breast tumor cells. Mol Biol Cell 18: 1768–1780, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chifflet S, Hernandez JA, Grasso S. A possible role for membrane depolarization in epithelial wound healing. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1420–C1430, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chmiel JF, Davis PB. State of the art: why do the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis become infected and why can't they clear the infection? Respir Res 4: 8, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coraux C, Roux J, Jolly T, Birembaut P. Epithelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions and stem cells in airway epithelial regeneration. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 689–694, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Da Paula AC, Ramalho AS, Farinha CM, Cheung J, Maurisse R, Gruenert DC, Ousingsawat J, Kunzelmann K, Amaral MD. Characterization of novel airway submucosal gland cell models for cystic fibrosis studies. Cell Physiol Biochem 15: 251–262, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denker SP, Barber DL. Cell migration requires both ion translocation and cytoskeletal anchoring by the Na-H exchanger NHE1. J Cell Biol 159: 1087–1096, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farooqui R, Fenteany G. Multiple rows of cells behind an epithelial wound edge extend cryptic lamellipodia to collectively drive cell-sheet movement. J Cell Sci 118: 51–63, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filali M, Liu X, Cheng N, Abbott D, Leontiev V, Engelhardt JF. Mechanisms of submucosal gland morphogenesis in the airway. Novartis Found Symp 248: 38–45, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frantz C, Karydis A, Nalbant P, Hahn KM, Barber DL. Positive feedback between Cdc42 activity and H+ efflux by the Na-H exchanger NHE1 for polarity of migrating cells. J Cell Biol 179: 403–410, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulcher ML, Gabriel SE, Olsen JC, Tatreau JR, Gentzsch M, Livanos E, Saavedra MT, Salmon P, Randell SH. Novel human bronchial epithelial cell lines for cystic fibrosis research. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L82–L91, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 426–436, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajj R, Baranek T, Le Naour R, Lesimple P, Puchelle E, Coraux C. Basal cells of the human adult airway surface epithelium retain transit-amplifying cell properties. Stem Cells 25: 139–148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajj R, Lesimple P, Nawrocki-Raby B, Birembaut P, Puchelle E, Coraux C. Human airway surface epithelial regeneration is delayed and abnormal in cystic fibrosis. J Pathol 211: 340–350, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haws C, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, Wine JJ. CFTR in Calu-3 human airway cells: channel properties and role in cAMP-activated Cl− conductance. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 266: L502–L512, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heguy A, Harvey BG, Leopold PL, Dolgalev I, Raman T, Crystal RG. Responses of the human airway epithelium transcriptome to in vivo injury. Physiol Genomics 29: 139–148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendriks R, Morest DK, Kaczmarek LK. Role in neuronal cell migration for high-threshold potassium currents in the chicken hindbrain. J Neurosci Res 58: 805–814, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, Fuchs E, Stripp BR. Basal cells are a multipotent progenitor capable of renewing the bronchial epithelium. Am J Pathol 164: 577–588, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingbar DH, Bhargava M, O'Grady SM. Mechanisms of alveolar epithelial chloride absorption. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L813–L815, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacinto A, Martinez-Arias A, Martin P. Mechanisms of epithelial fusion and repair. Nat Cell Biol 3: E117–E123, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight DA, Holgate ST. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Respirology 8: 432–446, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Clainche C, Carlier MF. Regulation of actin assembly associated with protrusion and adhesion in cell migration. Physiol Rev 88: 489–513, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Engelhardt JF. The glandular stem/progenitor cell niche in airway development and repair. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 682–688, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lock JG, Wehrle-Haller B, Stromblad S. Cell-matrix adhesion complexes: master control machinery of cell migration. Semin Cancer Biol 18: 65–76, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meima ME, Mackley JR, Barber DL. Beyond ion translocation: structural functions of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform-1. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 365–372, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 373: 1891–1904, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer ML, Lee SY, Carlson D, Fahrenkrug S, O'Grady SM. Stable knockdown of CFTR establishes a role for the channel in P2Y receptor-stimulated anion secretion. J Cell Physiol 206: 759–770, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer ML, Lee SY, Maniak PJ, Carlson D, Fahrenkrug SF, O'Grady SM. Protease-activated receptor regulation of Cl− secretion in Calu-3 cells requires prostaglandin release and CFTR activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1189–C1198, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulsen JH, Fischer H, Illek B, Machen TE. Bicarbonate conductance and pH regulatory capability of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 5340–5344, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puchelle E, Zahm JM, Tournier JM, Coraux C. Airway epithelial repair, regeneration, and remodeling after injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 726–733, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Putney LK, Denker SP, Barber DL. The changing face of the Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE1: structure, regulation, and cellular actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 527–552, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy MM, Quinton PM. Control of dynamic CFTR selectivity by glutamate and ATP in epithelial cells. Nature 423: 756–760, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302: 1704–1709, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riordan JR. CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 701–726, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 352: 1992–2001, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwab A. Ion channels and transporters on the move. News Physiol Sci 16: 29–33, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwab A, Nechyporuk-Zloy V, Fabian A, Stock C. Cells move when ions and water flow. Pflügers Arch 453: 421–432, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwab A, Reinhardt J, Schneider SW, Gassner B, Schuricht B. K(+) channel-dependent migration of fibroblasts and human melanoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 9: 126–132, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwab A, Wojnowski L, Gabriel K, Oberleithner H. Oscillating activity of a Ca(2+)-sensitive K+ channel. A prerequisite for migration of transformed Madin-Darby canine kidney focus cells. J Clin Invest 93: 1631–1636, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen BQ, Finkbeiner WE, Wine JJ, Mrsny RJ, Widdicombe JH. Calu-3: a human airway epithelial cell line that shows cAMP-dependent Cl− secretion. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 266: L493–L501, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sparrow MP, Omari TI, Mitchell HW. The epithelial barrier and airway responsiveness. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 73: 180–190, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stock C, Gassner B, Hauck CR, Arnold H, Mally S, Eble JA, Dieterich P, Schwab A. Migration of human melanoma cells depends on extracellular pH and Na+/H+ exchange. J Physiol 567: 225–238, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stock C, Mueller M, Kraehling H, Mally S, Noel J, Eder C, Schwab A. pH nanoenvironment at the surface of single melanoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 20: 679–686, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarran R, Button B, Picher M, Paradiso AM, Ribeiro CM, Lazarowski ER, Zhang L, Collins PL, Pickles RJ, Fredberg JJ, Boucher RC. Normal and cystic fibrosis airway surface liquid homeostasis. The effects of phasic shear stress and viral infections. J Biol Chem 280: 35751–35759, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor GW, Chopra DP, Mathieu PA. Differences in secretory profiles of epithelial cell cultures derived from human tracheal and bronchial mucosa and submucosal glands. Epithelial Cell Biol 2: 163–169, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tesei A, Zoli W, Arienti C, Storci G, Granato AM, Pasquinelli G, Valente S, Orrico C, Rosetti M, Vannini I, Dubini A, Dell'Amore D, Amadori D, Bonafe M. Isolation of stem/progenitor cells from normal lung tissue of adult humans. Cell Prolif 42: 298–308, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trapnell BC, Chu CS, Paakko PK, Banks TC, Yoshimura K, Ferrans VJ, Chernick MS, Crystal RG. Expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene in the respiratory tract of normal individuals and individuals with cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 6565–6569, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Roberts BC, Proia AD. Basal-like cells constitute the proliferating cell population in cystic fibrosis airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 1013–1018, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, Forrester JV, McCaig CD. Direct visualization of a stratified epithelium reveals that wounds heal by unified sliding of cell sheets. FASEB J 17: 397–406, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]