Abstract

Phenol is a neurolytic agent used for management of spasticity in patients with either motoneuron lesions or stroke. In addition, compounds that enhance muscle contractility (i.e., polyphenols, etc.) may affect muscle function through the phenol group. However, the effects of phenol on muscle function are unknown, and it was, therefore, the purpose of the present investigation to examine the effects of phenol on tension development and Ca2+ release in intact skeletal muscle fibers. Dissected intact muscle fibers from Xenopus laevis were electrically stimulated, and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) and tension development were recorded. During single twitches and unfused tetani, phenol significantly increased [Ca2+]c and tension without affecting myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. To investigate the phenol effects on Ca2+ channel/ryanodine receptors, single fibers were treated with different concentrations of caffeine in the presence and absence of phenol. Low concentrations of phenol significantly increased the caffeine sensitivity (P < 0.01) and reduced the caffeine concentrations necessary to produce nonstimulated contraction (contracture). However, at high phenol concentrations, caffeine did not increase tension or Ca2+ release. These results suggest that phenol affects the ability of caffeine to release Ca2+ through an effect on the ryanodine receptors, or on the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump. During tetanic contractions inducing fatigue, phenol application decreased the time to fatigue. In summary, phenol increases intracellular [Ca2+] during twitch contractions in muscle fibers without altering myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and may be used as a new agent to study skeletal muscle Ca2+ handling.

Keywords: excitation-contraction coupling, caffeine, ryanodine receptors, fatigue

phenol (hydroxybenzene) is an organic compound used in the treatment of spasticity, which is a neuromuscular disorder that promotes motoneuronal hyperexcitability and affects patients who have either upper motoneuron lesions (26) or stroke (27). To reduce spasticity, either botulinum toxin or phenol is injected in the motor point of the affected muscle (8). The phenol action involves blockage of the motoneuron by injections (3–6% aqueous solutions) at the motor point, which promote neurodenervation (5, 8). Interestingly, these injections have been shown to increase muscle strength (27).

Skeletal muscle contractility is highly dependent on Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) during excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. During the E-C coupling, L-type Ca2+ channel/dihydropyridine receptors, present in the transverse tubule membrane, change their conformation and open the SR Ca2+ channel ryanodine receptor (Ryr) (16). When cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]c) is sufficiently high to bind to the low-affinity sites of troponin C ([Ca2+]c ≥ 0.6 μM), it triggers muscle contraction by activating the cross-bridge cycle (38, 39).

Different phenol derivatives, like thymol and chorocresol, can increase Ca2+ release from Ryr. These effects were studied on either SR vesicles from skeletal muscle or reconstituted planar lipid bilayers (33, 40, 45). Furthermore, some polyphenols, such as quercetin and doxorubicin, also increase Ca2+ release in skinned skeletal muscle fibers and increase the open probability of Ca2+ channel/Ryr in SR vesicles (24, 34, 44). These compounds have been proposed to increase muscle performance during contractile work bouts (10, 22). However, the specific effects of phenol or these polyphenols on muscle contractility and Ca2+ release properties have never been studied carefully in an intact muscle system.

In intact skeletal muscle fibers, intracellular [Ca2+], representing the net change in the cytosolic Ca2+ based on Ca2+ release and Ca2+ re-uptake by the SR, can be studied using fluorescent probes to measure real-time Ca2+ transients in the cytosol during electrical stimulation (21, 25). In these single myofibers, Ca2+ release properties can be studied without confounding factors related to whole muscle preparations (32). The purpose of the present study was to test the hypothesis, using single isolated muscle fibers, that phenol increases Ryr activity during contractions, thereby increasing both tension development and Ca2+ release from the SR. In addition, we examined the effects of phenol on muscle fatigability and Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care and single-fiber isolation.

Female adult Xenopus laevis were used in this investigation. All procedures were approved by the University of California, San Diego institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) and conform to American Physiological Society and National Institutes of Health guidelines. The animals were anesthetized, double pithed, and decapitated, and the lumbrical muscles (II-IV) were removed. Single skeletal muscle fibers (n = 22) were isolated using a pair of scissors and forceps under dark-field illumination. Primarily fast-twitch, glycolytic skeletal muscle fibers were selected for use in the present study, as described previously (37). Dissection and experiment were performed in Ringer solution containing (in mM) 116.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.9 CaCl2, 2 NaH2PO4, and 0.1 EGTA, pH 7.0, at room temperature (20–22°C).

Experimental protocol.

Following dissection and isolation, platinum clips were attached to the tendons, and each fiber was mounted in a single muscle strip myograph system (model 920CS, Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) and placed on the stage of an inverted microscope. Single twitches (1 Hz) of 2-ms duration at 8–10 V and tetanic contractions (10–150 Hz) with train duration of 250 ms were induced by direct stimulation, using a Grass S48 stimulator (Quincy, MA). Tension development was measured with a force transducer system (model KG4, 0–50 mN, Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). A Biopac Systems MP100WSW (Santa Barbara, CA) analog-to-digital converter was used to convert the analog to digital data, and AcqKnowledgeIII 3.2.6 software (Biopac Systems) was used to analyze the data. Before each experiment, sarcomere length that promotes the maximal isometric tension was determined by stretching the fiber to develop maximal tetanic tension (70 Hz). After setting maximal isometric tension, the fiber was allowed to rest for 30 min.

Phenol was solubilized with Ringer solution and adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH. Phenol solution (1% wt/vol) was prepared on the day of the experiment to avoid changes in the stock concentration by volatilization. Before the phenol treatments, a force-frequency curve was obtained, stimulating the fiber at different frequencies (1–150 Hz) with 1-min interval between stimulations. This procedure provided information about control twitch tensions, as well as fused and unfused tetanic contractions for each fiber (23).

To study the effects of phenol on twitch tension (1-Hz stimulation), a twitch contraction was evoked after the force-frequency curve. Phenol (0.005–0.05% wt/vol) was applied directly to the chamber bath, followed by another twitch contraction in the presence of phenol. To avoid residual phenol in the chamber bath between phenol concentrations, the fiber was washed three times with Ringer solution. In some fibers (n = 4), the force-frequency curve was evoked in the presence and absence of phenol. In these cases, phenol effects were tested after each frequency of stimulation and then washed out for the next frequency. Each tension developed (P) was analyzed relative to the maximal tetanic tension obtained at 150-Hz stimulation (P0) in the absence of phenol. All of the tension development data were reported as P/P0.

The fatigue-inducing contraction bout utilized in the present study consisted of a series of increments in train frequency at 70 Hz (control condition) or 30 Hz (0.03% phenol), using 0.125, 0.166, 0.25, 0.33, and 0.5 contractions/s for 2 min each, until the fatigue point, which was defined as the decrease in tension to 50% maximal tension developed in that contractile run. These different stimulation frequencies (70 and 30 Hz) were used because they elicit very similar tension development and [Ca2+]c between the control and phenol conditions (see results), thereby producing similar energy demand. Each fiber (n = 4) performed two fatigue runs separated by 60-min rest. It has previously been shown that this time period between contractile periods allows complete recovery of the myofiber (36). As the effects of phenol are completely reversible, in two fibers the first run was a control, followed by the 0.03% phenol fatigue run, and, in two fibers, the fatigue run with phenol was conducted before the control run.

In the experiments in which caffeine was used to increase twitch tension and Ca2+ release in single fibers, a stock solution of 5 mM caffeine was prepared with Ringer solution and pH adjusted to 7.0 with KOH. Each fiber was exposed to different caffeine concentrations (10 μM to 2 mM), applied directly to the chamber bath, and then followed by single-twitch stimulation and washout. Low concentrations of caffeine that are known not to increase force (10–100 μM caffeine) (32), medium concentrations that increase force (250 μM to 1 mM caffeine) (6), and high concentrations that open Ryr and produce contracture (i.e., tension development without electrical stimulation; [caffeine] > 1.5 mM) were used on fibers in the absence or presence of phenol (0.005–0.04%). In this procedure, 1.5–2.5 mM caffeine were sufficient to induce contracture in the absence of phenol. The same caffeine dose responses were carried out in the presence of phenol (0.005–0.04%), until the fiber developed contracture.

Ca2+ fluorescence.

[Ca2+]c was obtained using fluorescence spectroscopy. After dissection and isolation, each fiber was pressure injected using a micropipette with the ratiometric Ca2+ indicator fura-2 (solubilized to 12 mM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Injected fibers were illuminated with two rapidly alternating (100–200 Hz) excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm, and the resulting fluorescence emissions at 510 nm were divided (340 nm/380 nm) to obtain the Ca2+-dependent signal, using a Photon Technology International illumination and detection system (DeltaScan model), integrated with a Nikon inverted microscope with a 40× Fluor objective. The peak of the fluorescence excitation ratio (340/380 nm) for each contraction was used to determine the relative peak [Ca2+]c. Calcium is reported as relative changes to peak.

Data analysis.

Relative force-frequency curves were fit by a sigmoid nonlinear regression using the equation P = Pmin + (P0·Xn/K0.5n + Xn), where P is the tension developed at different frequencies of stimulation, Pmin is the minimum tension developed, K0.5 is the midpoint of the curve, and n is nH, the Hill coefficient, which is correlated to the steepness of the curve. The result of fitting each experiment and taking the mean values of the individual K0.5 and nH values within each data set are reported in the text. The experimental results are presented as means ± SE. For comparison between two groups, paired Student's t-test was used. For multiple comparisons, a one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test or a two-way ANOVA was used, as indicated. Analyses were carried out using PRISM 4 software, and P < 0.05 was considered to represent significant difference.

RESULTS

Effects of phenol on Ca2+ release and twitch tension development in intact skeletal muscle fibers.

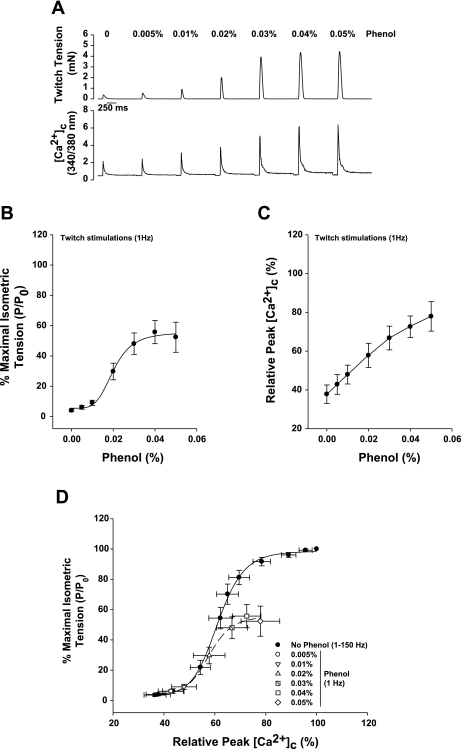

Single-twitch stimulation (1 Hz) promotes a submaximal increase in intracellular [Ca2+], due primarily to the release of Ca2+ from the SR (7). Initially, we investigated whether twitch force and [Ca2+]c are affected by phenol in single-muscle fibers (n = 9). Phenol was diluted directly into the fiber bath to reach the concentrations shown in Fig. 1, followed by single-twitch stimulation in the presence of phenol. The results were compared with the control force-frequency curve (see materials and methods). Figure 1A shows a representative recording of twitch tension and [Ca2+]c during a dose-response curve with phenol in a single fiber.

Fig. 1.

Twitch tensions are increased by phenol in a dose-response pattern in single fibers from Xenopus laevis. A: representative force and fura-2 fluorescence recordings from a single fiber during twitch activation (1 Hz) in the presence of 0.005–0.05% phenol. B: the twitch force response to phenol treatment shows a sigmoid relationship with a midpoint of 0.024 ± 0.003% phenol. C: relative peak cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]c) responses to phenol treatment during single-twitch contractions. D: relationship between twitch force-[Ca2+]c plotted against the force-[Ca2+]c curve obtained from a force-frequency curve. There is no change in Ca2+ sensitivity on any of the phenol concentrations tested. Values are means ± SE; n = 9 fibers. P/P0, tension developed (P) analyzed relative to the maximal tetanic tension obtained at 150-Hz stimulation (P0).

Twitch tension was significantly increased from 4 ± 1 to 52 ± 10% of the maximal tension at 0.05% phenol (Fig. 1B, P < 0.001) in a sigmoid fashion. The phenol concentration that promotes 50% of the maximal activation in fibers, calculated from each dose-response curve, was 0.024 ± 0.003% (n = 9). The relative [Ca2+]c during each twitch contraction, measured from fura-2 fluorescence (see materials and methods), was significantly increased by phenol from 38 ± 5 to 78 ± 8% of the maximal peak [Ca2+]c at 0.05% phenol (Fig. 1C, P < 0.001). When a single-twitch tension-peak [Ca2+]c relationship, in the presence of phenol, was plotted and compared with the isometric tension-peak [Ca2+]c relationship constructed from the control force-frequency curve, there was no difference in the midpoint between the two curves (Fig. 1D), calculated by the relative [Ca2+]c that promotes the 50% of the maximum tension produced in each condition (data not shown).

Phenol does not increase the maximal Ca2+ release and tetanic tension in intact skeletal muscle fibers.

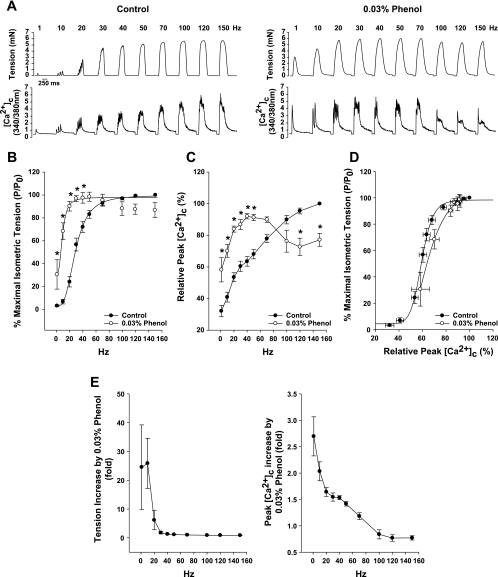

To investigate whether phenol increases maximal tension or maximal peak [Ca2+]c, another group of fibers (n = 4) was stimulated at different frequencies in the presence and absence of 0.03% phenol. This concentration of phenol was chosen because it is close to the activation midpoint (Fig. 1B). Figure 2A shows an original force and [Ca2+]c recording from a representative fiber during a contraction at different frequencies before (left panel) and after 0.03% phenol treatment (right panel).

Fig. 2.

Phenol increases force and [Ca2+]c at lower frequencies of stimulation. A: representative isometric tensions and fura-2 fluorescence ([Ca2+]c) recordings in the same single fiber before (left) and after 0.03% phenol (right) during a force-frequency curve. B–D: relative isometric tension (B) and relative peak [Ca2+]c (C) are higher in the presence of phenol at submaximal frequencies (*P < 0.05 vs. control, two-way ANOVA), but there is no change in Ca2+ sensitivity (D) between conditions. E: absolute tension (left) or peak [Ca2+]c (right) in the presence of phenol was divided for the control values at each frequency, showing that the enhancing effect of phenol is higher at 1 Hz. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 fibers.

Phenol increased twitch and tetanic isometric tensions at submaximal frequencies of stimulation (1–40 Hz), compared with the same frequencies without phenol treatment (Fig. 2B, *P < 0.05). However, at higher frequencies with phenol, the developed tensions showed a tendency for inhibition, but were not significantly different from the control (P > 0.05). The curves shown in Fig. 2B were fit using a sigmoid Hill curve, as described in materials and methods, and demonstrated a significant left shift with phenol (K0.5 for the control curve is 26 ± 3 Hz and for 0.03% phenol is 10 ± 1 Hz, P < 0.05, paired t-test), but no difference in the steepness of the curve (nH is 3.5 ± 0.6 for control and 3.5 ± 0.9 for 0.03% phenol, P > 0.05).

The relative peak [Ca2+]c responses with phenol (Fig. 2C) followed the same pattern as that of the isometric tension. Cytosolic calcium transients were significantly higher at low frequencies of stimulation (Fig. 2C, *P < 0.05 vs. control). Nonetheless, at high frequencies (100–150 Hz), phenol inhibited relative peak [Ca2+]c responses (Fig. 2A, right, and Fig. 2C, *P < 0.05 vs. control).

In Fig. 2D, the relationship between isometric tension and peak [Ca2+]c was established, plotting the relative tension (P/P0) vs. relative peak [Ca2+]c, obtained from Fig. 2, B and C. In the case of 0.03% phenol, both tension and [Ca2+]c were obtained from low frequencies of stimulation (1–50 Hz) to avoid possible deleterious effects of phenol under higher frequencies of stimulation. The comparison between control and 0.03% phenol shows that there was no significant shift in the tension-[Ca2+]c relationship (Fig. 2D).

The change promoted by phenol in force and calcium release at different frequencies was calculated by dividing the data obtained during phenol treatment by the data obtained during control conditions. In Fig. 2E, it is shown that the enhancement produced by phenol is higher at low frequencies (1–20 Hz), which produce single-twitch and unfused tetani (i.e., less calcium being released), and disappeared at high frequencies (>30 Hz), which produce fused tetani (Fig. 2E, n = 4 fibers).

Effects of caffeine on tension and calcium release in the presence of phenol.

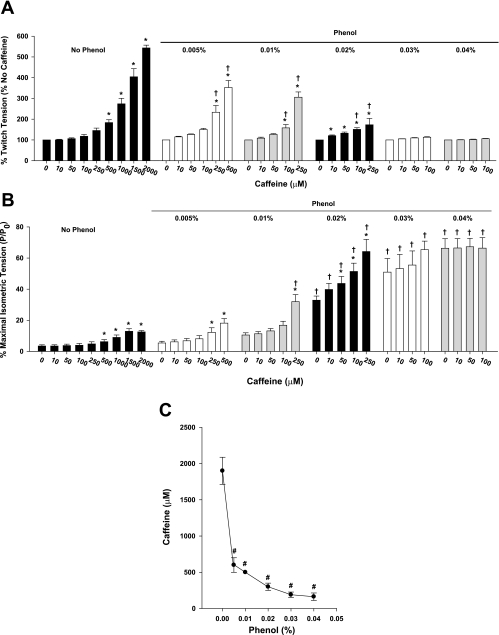

Since phenol increases [Ca2+]c at twitch and submaximal tetanic contractions, we investigated whether the increase in cytosolic calcium was induced by enhancement of Ca2+ release from Ryr. Figure 3 summarizes the data obtained with five single, intact muscle fibers electrically stimulated to produce single twitches (1 Hz). Without phenol, caffeine increased twitch tension in a dose-dependent manner, and the minimum caffeine concentration necessary to increase twitch tension was 500 μM (Fig. 3A, *P < 0.05). The [Ca2+]c, measured from fura-2 fluorescence during contractions, followed the increase in twitch tension by caffeine (data not shown). Presence of low concentrations of phenol (0.005–0.02%) decreased the minimum caffeine necessary to increase the twitch force (i.e., increase in caffeine sensitivity), being 250 μM caffeine for 0.005% phenol, 100 μM caffeine for 0.01% phenol, and 10 μM caffeine for 0.02% phenol (Fig. 3A, *P < 0.05). Interestingly, when the phenol concentration was 0.03 and 0.04%, there was no significant increase in both twitch force (Fig. 3A) and [Ca2+]c (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Phenol increases caffeine sensitivity in single skeletal muscle fibers. Single fibers were exposed to different caffeine concentrations (10 μM to 2 mM) until the fiber started developing contracture. The same treatment was carried out in the presence of phenol (0.005–0.04%). A: relative increase in twitch tension by caffeine shows that, at low-phenol concentrations (0.005–0.02%), caffeine sensitivity is increased. B: twitch tension relative to maximal isometric tetanic tension (P/P0) shows that, at high-phenol concentrations, caffeine is unable to promote increase in force. *P < 0.05 vs. no caffeine for each phenol concentration, one-way ANOVA. †P < 0.05 vs. no phenol for respective caffeine concentration, two-way ANOVA. C: caffeine concentrations necessary to promote “rigor state” in single skeletal muscle fibers exposed to phenol (0.005–0.04%). #P < 0.001 vs. no phenol, one-way ANOVA. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 fibers.

When the data are normalized to the maximum isometric tetanic tension (P/P0; Fig. 3B), phenol by itself promoted a significant increase in twitch tension (Fig. 3B, †P < 0.05) and [Ca2+]c (data not shown, P < 0.05). At high concentrations of phenol (0.03 and 0.04%), there was no change in twitch tension with caffeine, but the force was maximally increased at all caffeine concentrations (Fig. 3B, †P < 0.05 vs. no phenol).

During the caffeine dose responses without phenol, there was a caffeine concentration that induces Ca2+ accumulation and tension without any stimulation (i.e., during rest). In the five fibers tested, 1.5 mM caffeine were necessary to induce contracture in two fibers, 2 mM caffeine were necessary in other two fibers, and one fiber exhibited contracture after exposure to 2.5 mM caffeine (1.9 ± 0.2 mM caffeine, Fig. 3C). During caffeine treatment in the presence of phenol, the concentration necessary to promote contracture decreased significantly when 0.005–0.04% phenol was present (Fig. 3C, #P < 0.001).

Effects of phenol on fatigue induced by tetanic contractions in intact single-muscle fibers.

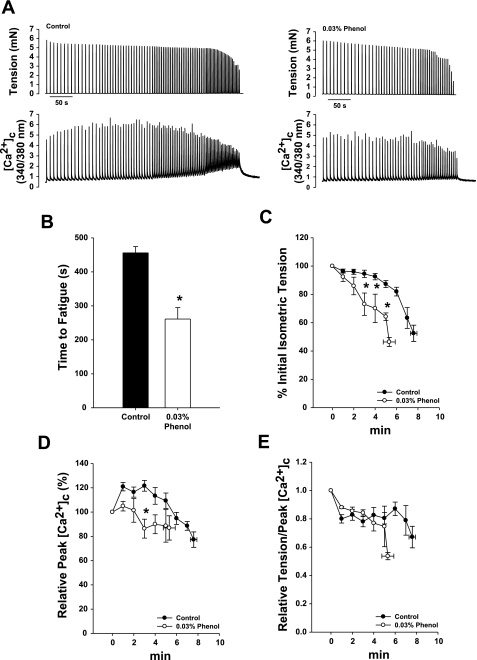

To determine whether the increase in twitch and submaximal tetanic tension promoted by phenol alters muscle performance, individual fibers (n = 4) were stimulated at progressively increasing tetanic contractions per second (as described in materials and methods) in the presence or absence of 0.03% phenol. Stimulation at 70 Hz for the control fatigue run was induced as described before (32) and at 30 Hz for the phenol fatigue run, since they evoke the same relative isometric tension and [Ca2+]c during each contraction (see Fig. 2, B and C). Figure 4A illustrates a typical fatigue run in one myocyte in which tetanic tension and cytosolic calcium were measured simultaneously before (left panel) and after 0.03% phenol treatment (right panel).

Fig. 4.

Fatigue is faster in single fibers when exposed to phenol. Single fibers were exposed to 0.03% phenol, followed by a fatigue protocol (0.125–0.5 contractions/s; 70-Hz stimulation) before (2 fibers) or after (2 fibers) a control fatigue protocol and recovery. A: representative tension and fura-2 fluorescence ([Ca2+]c) recordings in the same single fiber before (left) and after 0.03% phenol (right) during fatigue protocol. B: mean time until the tension generated had decreased to 50% of the initial tension (fatigue point) without (control) and with 0.03% phenol in the bath (*P < 0.05, paired t-test). C: relative tension measurements show that phenol reduces the tetanic tension faster during fatigue protocol (*P < 0.05 vs. control, two-way ANOVA). D: peak [Ca2+]c is not significantly different from control during fatigue protocol. E: relationship between tetanic tension and peak [Ca2+]c during fatigue shows that the Ca2+ sensitivity is changed only at the fatigue point in either control or phenol treatment. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 fibers.

Phenol reduced the fatigue time to 57 ± 7% of the control (Fig. 4B, *P < 0.05). Moreover, isometric tension at the same time points were reduced by phenol compared with the control (Fig. 4C, *P < 0.05). Phenol also impaired the early increase in maximal Ca2+ release that normally happens during a fatigue run (20, 25) (Fig. 4D, *P < 0.05).

Figure 4E illustrates the ratio of relative tetanic tension and peak cytosolic calcium, an index of Ca2+ sensitivity during the fatigue run (2). With phenol, the ratio was not changed during the fatigue run compared with the control run. However, the ratio, which decreases at the fatigue point for both control and phenol runs, occurs earlier when phenol is present.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of the present investigation is that phenol potentiates twitch tension and unfused tetanic contractions in intact skeletal muscle fibers. Specifically, our results demonstrate the following. 1) Phenol increases single-twitch tension (1-Hz stimulation) and submaximal tetanic contractions elicited by low frequencies of stimulation mainly by increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (likely via an increase in SR Ca2+ release), which activates the myofilaments and promotes an increase in force. Furthermore, there is no increase in Ca2+-sensitivity or maximum force as shown by the force-Ca2+ relationship. 2) Phenol increases the caffeine sensitivity of the SR in intact single fibers, which suggests that phenol and caffeine cooperatively interact with Ryr. Also, 3) during a fatigue run, phenol decreases time to fatigue and inhibits the early rise in [Ca2+]c at the initiation of contractile activity (see Fig. 4D).

Physiological relevance of the effects of phenol on skeletal muscle function.

During the treatment of spasticity, phenol is injected close to the motor point in one or different locations of the target muscle to promote denervation to stop the hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex (5). The concentrations of phenol that promoted the main effects in intact fibers (0.005–0.05% wt/vol) in the present study were significantly lower than those used for spasticity treatment and neurodenervation (3–6% wt/vol) (5, 8). When we tested concentrations >0.05% phenol, both tension and Ca2+ release were completely abolished (data not shown). This suggests that, at higher concentrations ([phenol] > 0.05%), phenol disrupts the E-C coupling, thereby impairing the contraction induced by stimulation, as happens at high concentrations with other phenol derivatives (3, 43). High concentrations of phenol (e.g., 5% aqueous solution) have been shown to produce muscle injury and necrosis (8, 28). Histochemical studies have shown that the motor point injections can also disrupt surrounding muscle fibers (28). However, not necessarily all of the fibers in the muscle will be exposed to the same phenol concentration, since the injections usually occur in one or more motor point areas, depending on the grade of neuronal injury (5). It is likely that deep muscle fibers are exposed to much lower phenol concentrations. It is possible that this is an explanation for the increased strength reported in a study that evaluated human muscle strength after phenol injections (27).

Phenol affects E–C coupling, but not the contractile proteins.

As described above, intact single fibers from skeletal muscle in the presence of phenol have increased twitch and low-frequency isometric tensions, which are correlated with the increased intracellular [Ca2+]. In our model, intact fibers are electrically stimulated to mimic the physiological stimulation by the motoneuron, which, in rodents, have a sustained discharge firing rate of 50–100 Hz for fast-twitch muscle and 10–20 Hz for slow-twitch fibers (18). At submaximal frequencies of stimulation, twitch and unfused tetanic contractions are evoked by submaximal cytosolic Ca2+ transients, as shown in this work (see Fig. 2A) and previous work (7). Phenol is able to increase [Ca2+]c during these submaximal frequencies of stimulation to increase force. However, at near-maximal frequencies (≥70 Hz), phenol does not produce any increases in either [Ca2+]c or tension, which suggests that phenol affects some mechanism between the membrane depolarization and either the SR Ca2+ release channels or the Ca2+ uptake pump. There are many reports of physiological and nonphysiological compounds that can increase either [Ca2+]c or tension development in intact muscle fibers at submaximal frequencies of stimulation, such as nitric oxide (4, 11), 4-chloro-m-cresol (43), terbutaline (7), and paraxanthine (17); in those studies, the main effect was the increase in the SR Ca2+ release channel activity.

Interestingly, we showed that the increased twitch tension, unfused tetanic tension, and [Ca2+]c during phenol treatment were not related to changes in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity, as shown in the relationship between developed tension and [Ca2+]c (see Figs. 1D and 2D). This suggests that phenol is not affecting Ca2+ binding to the troponin complex nor cross-bridge interaction [that can change the thin-filament Ca2+ sensitivity (31)]. This is important as it shows the specificity of the effect of phenol on the SR Ca2+ regulatory events in skeletal muscle fibers.

Comparison with the effects of other phenol derivatives in skeletal muscle and in Ryr.

Phenol shares the basic chemical structure of many other organic compounds that are known as Ca2+ release activators in both skeletal and cardiac muscles, such as cresols, chlorocresols, chlorophenols, and flavonoids (12, 24, 33, 40, 44–45). Although they have different sensitivities to induce Ca2+ release from the SR, it is suggested that all of them exhibit their effects because they interact with the large hydrophobic site present in the Ryr (12, 16, 45). Some of the phenol derivatives can act as redox cycling compounds and may promote oxidative changes in the Ryr. However, the effects of phenol are instantaneously and completely reversible, as seen with doxorubicin (44) or N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN) (3), so it is unlikely that phenol is inducing oxidative changes in the Ryr. Although other phenol derivatives can increase intracellular [Ca2+] through interactions with Ryr, they do not necessarily interact in the same site of Ryr or in the same site that caffeine interacts with Ryr (e.g., quercetin) (24). However, all of those phenollike compounds have been compared with the effect of caffeine on Ca2+ release (24, 30, 40, 44, 45). This demonstrates that there is a close relationship between caffeine and phenol derivatives on the Ryr function, even if they do not share the same binding site, as determined in muscle cell lines when the binding sites for caffeine and 4-chloro-m-cresol were identified in vitro (12, 13). Although the effects of phenol and other phenol derivatives are likely due by increase in SR Ca2+ release, we cannot eliminate a possible inhibitory effect of phenol on SR Ca2+ reuptake. There is a report that another phenol derivative, 4-chloro-m-cresol, inhibits the SR Ca2+ uptake pump [sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)] (1). However, the concentration of 4-chloro-m-cresol necessary to inhibit SERCA is 5–10× higher than the concentration needed to increase SR Ca2+ release from Ryr (1, 14, 43). Furthermore, phenol treatment does not increase resting [Ca2+]c, which is expected when SERCA is inhibited in intact fibers (42). Together, we think it is unlikely that phenol inhibits the SR Ca2+ reuptake.

It is important to note that only one phenol derivative has been studied in an intact physiological system, Westerblad et al. (43) showed that 4-chloro-m-cresol treatment in mouse single fibers increases resting and depolarization-induced [Ca2+]c and tetanic tension, as well as contracture induced by caffeine. However, phenol has marked higher effects on tension development and intracellular [Ca2+], possibly related to the difference in the preparation (amphibian muscle vs. mammalian muscle). In the present study, we demonstrate that phenol is a strong activator of Ryr, based on the increased caffeine sensitivity in intact fibers when phenol was present, and thereby suggests that phenol and caffeine bind at different activating sites in Ryr, and that there is an alosteric effect between caffeine and many phenolytic compounds. In addition, Andersen et al. (3), using the aromatic compound PBN in contracting diaphragm muscle strips, showed reversible increases in isometric tension at low frequencies of stimulation. When these results (3) are compared with the phenol effects shown in the present work, the enhancement in twitch tension promoted by phenol (∼25-fold) is much higher than PBN (∼40% increase) (3). This work by Andersen et al. (3) also demonstrated that high concentrations of PBN (e.g., 10 mM) blocks the E-C coupling in skeletal muscle strips, as shown for phenol ([phenol] > 0.05%).

It is known that caffeine promotes Ca2+ release from the SR by increasing the lifetime of the Ryr opening, changing it to an open-state channel (16, 24, 29). In intact single fibers from frog and mouse skeletal muscle, high concentrations of caffeine (e.g., 5 mM) are commonly used to increase [Ca2+]c and tension in fatigued fibers to investigate SR function (6, 32, 35). The present data show that the minimum caffeine necessary to increase twitch tension and [Ca2+]c is significantly reduced when submaximal phenol concentrations are present. However, at the same time, phenol by itself increases twitch tension and [Ca2+]c. At near-maximal phenol concentrations (0.03–0.04% wt/vol), both twitch tension and [Ca2+]c are not affected by caffeine. This can be explained by a comparison between the caffeine and phenol effect on increasing twitch tension: phenol increases tension four times more than caffeine. Therefore, it is unlikely that caffeine can increase either [Ca2+]c or twitch tension in the presence of near-maximal phenol concentrations. The caffeine concentration necessary to increase resting [Ca2+]c and unstimulated tension development (contracture) is significantly reduced in the presence of phenol. These data suggest that the effects of phenol and caffeine are interactive and that they act synergistically to elevate intracellular [Ca2+] and force production.

Fatigability is enhanced when phenol is present during contractions.

During repeated tetani up to the fatigue point (50% of the initial tetanic tension), the ATP necessary for the work is provided by phosphocreatine breakdown by creatine kinase (CK), anaerobic glycogenolysis, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (for review, see Ref. 2), and the importance of each metabolic pathway during repetitive contractions is fiber-type dependent. When diaphragm muscle strips were treated with PBN, there was a decreased in time to fatigue (∼30% reduction) (3). We found that phenol reduces the time to fatigue to ∼40% of the control. Interestingly, phenol impairs the increase in [Ca2+]c that follows the beginning of contractile activity, as shown in the control curve (see Fig. 4D). Nevertheless, this effect is not related to a reduction in cross-bridge force generation, because the relationship between tension and [Ca2+]c is reduced the same magnitude with phenol, compared with control.

Our group has previously shown (20) that the increased [Ca2+]c at the beginning of contractile activity is completely blocked during acute CK inhibition in Xenopus single fibers, and the same was demonstrated in CK−/− mice (9). In this work (9), when phosphate was injected into the fibers to mimic Pi accumulation by CK activity, the initial increased [Ca2+]c returned to the wild-type pattern. The SR Ca2+ release is increased by Pi binding to Ryr (15), which suggests that Pi is a major activator of increased [Ca2+]c in the beginning of a fatigue run. It is possible that phenol either impairs the Pi binding to Ryr during a fatigue run, or promotes conformational changes in Ryr to a “preactivated” state, in which Pi does not have an effect on Ryr activation.

In intact muscle fibers near the fatigue point, there is a marked decrease in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity that is associated with acidosis and/or Pi accumulation in the cytosol (2). The present data show that, during a fatigue run in the presence of phenol, there is an earlier reduction in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (see Fig. 4E). This could be associated with faster acidosis development, since other phenol derivatives (e.g., quercetin) are used as an inhibitor of the monocarboxylate transporter, which has an important role in the lactate efflux in skeletal muscle (19). In case the lactate efflux is impaired, glycolysis will be inhibited, and fatigue will occur earlier (41). To address this question, more experiments are necessary to verify whether phenol can act as a lactate transporter inhibitor (as quercetin).

In summary, we demonstrate that phenol increases submaximal intracellular [Ca2+], likely due to the increase in SR Ca2+ release, as well as the twitch tension, during contractions in intact skeletal muscle fibers, without changing the Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments. In addition, phenol increases caffeine sensitivity in single fibers, which suggests that the action of phenol is directly on skeletal muscle Ryr. These findings establish phenol as an important tool to study Ryr function and calcium handling in skeletal muscle and may suggest a mechanism by which polyphenols may affect muscle contractility.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant AR40155.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. A. E. Knapp (UCSD) for critical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al-Mousa F, Michelangeli F. Commonly used ryanodine receptor activator, 4-chloro-m-cresol (4CmC), is also an inhibitor of SERCA Ca2+ pumps. Pharmacol Rep 61: 838–842, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev 88: 287–332, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersen KA, Diaz PT, Wright VP, Clanton TL. N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone: a free radical trap with unanticipated effects on diaphragm function. J Appl Physiol 80: 862–868, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of nitric oxide on single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol 509: 577–586, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Botte MJ, Keenan MA. Percutaneous phenol blocks of the pectoralis major muscle to treat spastic deformities. J Hand Surg [Am] 13: 147–149, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruton JD, Lannergren J, Westerblad H. Effects of repetitive tetanic stimulation at long intervals on excitation-contraction coupling in frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol 495: 15–22, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cairns SP, Westerblad H, Allen DG. Changes of tension and [Ca2+]i during beta-adrenoceptor activation of single, intact fibres from mouse skeletal muscle. Pflügers Arch 425: 150–155, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cullu E, Ozkan I, Culhaci N, Alparslan B. A comparison of the effect of doxorubicin and phenol on the skeletal muscle. May doxorubicin be a new alternative treatment agent for spasticity? J Pediatr Orthop B 14: 134–138, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dahlstedt AJ, Katz A, Tavi P, Westerblad H. Creatine kinase injection restores contractile function in creatine-kinase-deficient mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 547: 395–403, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis JM, Murphy EA, Carmichael MD, Davis B. Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1071–R1077, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eu JP, Hare JM, Hess DT, Skaf M, Sun J, Cardenas-Navina I, Sun QA, Dewhirst M, Meissner G, Stamler JS. Concerted regulation of skeletal muscle contractility by oxygen tension and endogenous nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 15229–15234, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fessenden JD, Feng W, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Amino acid residues Gln4020 and Lys4021 of the ryanodine receptor type 1 are required for activation by 4-chloro-m-cresol. J Biol Chem 281: 21022–21031, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fessenden JD, Perez CF, Goth S, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Identification of a key determinant of ryanodine receptor type 1 required for activation by 4-chloro-m-cresol. J Biol Chem 278: 28727–28735, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fessenden JD, Wang Y, Moore RA, Chen SR, Allen PD, Pessah IN. Divergent functional properties of ryanodine receptor types 1 and 3 expressed in a myogenic cell line. Biophys J 79: 2509–2525, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fruen BR, Mickelson JR, Shomer NH, Roghair TJ, Louis CF. Regulation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptor by inorganic phosphate. J Biol Chem 269: 192–198, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors. Cell Calcium 38: 253–260, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawke TJ, Allen DG, Lindinger MI. Paraxanthine, a caffeine metabolite, dose dependently increases [Ca2+]i in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 89: 2312–2317, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hennig R, Lomo T. Firing patterns of motor units in normal rats. Nature 314: 164–166, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Juel C, Halestrap AP. Lactate transport in skeletal muscle–role and regulation of the monocarboxylate transporter. J Physiol 517: 633–642, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kindig CA, Howlett RA, Stary CM, Walsh B, Hogan MC. Effects of acute creatine kinase inhibition on metabolism and tension development in isolated single myocytes. J Appl Physiol 98: 541–549, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kindig CA, Stary CM, Hogan MC. Effect of dissociating cytosolic calcium and metabolic rate on intracellular Po2 kinetics in single frog myocytes. J Physiol 562: 527–534, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, Messadeq N, Milne J, Lambert P, Elliott P, Geny B, Laakso M, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 127: 1109–1122, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lannergren J, Westerblad H. The temperature dependence of isometric contractions of single, intact fibres dissected from a mouse foot muscle. J Physiol 390: 285–293, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee EH, Meissner G, Kim DH. Effects of quercetin on single Ca2+ release channel behavior of skeletal muscle. Biophys J 82: 1266–1277, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee JA, Westerblad H, Allen DG. Changes in tetanic and resting [Ca2+]i during fatigue and recovery of single muscle fibres from Xenopus laevis. J Physiol 433: 307–326, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mayer NH. Clinicophysiologic concepts of spasticity and motor dysfunction in adults with an upper motoneuron lesion. Muscle Nerve Suppl 6: S1–S13, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCrea PH, Eng JJ, Willms R. Phenol reduces hypertonia and enhances strength: a longitudinal case study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 18: 112–116, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nathan PW, Sears TA, Smith MC. Effects of phenol solutions on the nerve roots of the cat: an electrophysiological and histological study. J Neurol Sci 2: 7–29, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ogawa Y, Murayama T, Kurebayashi N. Comparison of properties of Ca2+ release channels between rabbit and frog skeletal muscles. Mol Cell Biochem 190: 191–201, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palade P. Drug-induced Ca2+ release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum. II. Releases involving a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release channel. J Biol Chem 262: 6142–6148, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinto JR, Veltri T, Sorenson MM. Modulation of troponin C affinity for the thin filament by different cross-bridge states in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Pflügers Arch 456: 1177–1187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosser JI, Walsh B, Hogan MC. Effect of physiological levels of caffeine on Ca2+ handling and fatigue development in Xenopus isolated single myofibers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1512–R1517, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sarkozi S, Almassy J, Lukacs B, Dobrosi N, Nagy G, Jona I. Effect of natural phenol derivatives on skeletal type sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and ryanodine receptor. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 28: 167–174, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shoshan V, Campbell KP, MacLennan DH, Frodis W, Britt BA. Quercetin inhibits Ca2+ uptake but not Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum in skinned muscle fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77: 4435–4438, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stary CM, Hogan MC. Impairment of Ca2+ release in single Xenopus muscle fibers fatigued at varied extracellular Po2. J Appl Physiol 88: 1743–1748, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stary CM, Hogan MC. Intracellular pH during sequential, fatiguing contractile periods in isolated single Xenopus skeletal muscle fibers. J Appl Physiol 99: 308–312, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stary CM, Mathieu-Costello O, Hogan MC. Resistance to fatigue of individual Xenopus single skeletal muscle fibres is correlated with mitochondrial volume density. Exp Physiol 89: 617–621, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stienen GJ, van Graas IA, Elzinga G. Uptake and caffeine-induced release of calcium in fast muscle fibers of Xenopus laevis: effects of MgATP and Pi. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C650–C657, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suarez MC, Machado CJ, Lima LM, Smillie LB, Pearlstone JR, Silva JL, Sorenson MM, Foguel D. Role of hydration in the closed-to-open transition involved in Ca2+ binding by troponin C. Biochemistry 42: 5522–5530, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Szentesi P, Szappanos H, Szegedi C, Gonczi M, Jona I, Cseri J, Kovacs L, Csernoch L. Altered elementary calcium release events and enhanced calcium release by thymol in rat skeletal muscle. Biophys J 86: 1436–1453, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Westerblad H, Allen DG. Changes of intracellular pH due to repetitive stimulation of single fibres from mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol 449: 49–71, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Westerblad H, Allen DG. The role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in relaxation of mouse muscle; effects of 2,5-di(tert-butyl)-1,4-benzohydroquinone. J Physiol 474: 291–301, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Westerblad H, Andrade FH, Islam MS. Effects of ryanodine receptor agonist 4-chloro-m-cresol on myoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration and force of contraction in mouse skeletal muscle. Cell Calcium 24: 105–115, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zorzato F, Salviati G, Facchinetti T, Volpe P. Doxorubicin induces calcium release from terminal cisternae of skeletal muscle. A study on isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum and chemically skinned fibers. J Biol Chem 260: 7349–7355, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zorzato F, Scutari E, Tegazzin V, Clementi E, Treves S. Chlorocresol: an activator of ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ release. Mol Pharmacol 44: 1192–1201, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]