Abstract

Each year millions of individuals sustain burns. Within the US 40,000–70,000 individuals are hospitalized for burn-related injuries, some of which are quite severe, requiring skin grafting. The grafting procedure disrupts neural and vascular connections between the host site and the graft, both of which are necessary for that region of skin to contribute to temperature regulation. With the use of relatively modern techniques such as laser-Doppler flowmetry and intradermal microdialysis, a wealth of information has become available regarding the consequences of skin grafting on heat dissipation and heat conservation mechanisms. The prevailing data suggest that cutaneous vasodilator capacity to an indirect heat stress (i.e., heating the individual but not the evaluated graft area) and a local heating stimulus (i.e., directly heating the graft area) is impaired in grafted skin. These impairments persist for ≥4 yr following the grafting procedures and are perhaps permanent. The capacity for grafted skin to vasodilate to an endothelial-dependent vasodilator is likewise impaired, whereas its capacity to vasodilate to an endothelial-independent vasodilator is generally preserved. Sweating responsiveness is minimal to nonexistent in grafted skin to both a whole body heat stress and local administration of the primary neurotransmitter responsible for stimulating sweat glands (i.e., acetylcholine). Likewise, there is no evidence that this absence of sweat gland responsiveness improves as the graft matures. In contrast to the heating stimuli, cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses to both indirect whole body cooling (i.e., exposing the individual to a cold stress but not at the evaluated graft area) and direct local cooling (i.e., directly cooling the graft area) are preserved in grafted skin as early as 5–9 mo postgrafting. If uninjured skin does not compensate for impaired heat dissipation of grafted skin, individuals having skin grafts encompassing significant fractions of their body surface area will be at a greater risk for a hyperthermic-related injury. Conversely, the prevailing data suggest that such individuals will not be at a greater risk of hypothermia upon exposure to cold environmental conditions.

every year approximately 1.4 million people in the US sustain burns (55), with 40,000–70,000 of these individuals requiring hospitalization (9, 41, 55) and 6,400 and 11,200 experiencing severe burns covering 20% or more of their body surface area (BSA) (2). Twenty years ago, burns covering one-half of a person's BSA were often fatal. However, due to medical advances, patients with burns covering up to 90% of their BSA are now surviving these injuries. Thus, more individuals are living with larger percentages of BSA of grafted skin than ever before. Military conflicts are also significant sources of burn-related injuries, given that 5–20% of all battlefield injuries are burn related (8, 11, 56).

Treatment of severe skin burns typically requires that most of or the entire dermal layer is excised. It is this dermal layer that, in noninjured skin, contains the blood vessels and sweat glands necessary for thermoregulation. This excised area is then covered with donor skin harvested from noninjured regions of the body. According to the Center for Disease Control, in 1996 approximately 191,000 skin-grafting procedures were performed in the US (3). These skin grafts are generally categorized as split-thickness or full-thickness grafts, with the overwhelming majority (≤90%) being split-thickness grafts. With split-thickness grafts, all of the epidermis and a portion of the dermis are removed from a donor site and grafted to the injured site. Since dermal structures such as the secretory coils of the sweat glands are deep within the dermal layer, most split-thickness grafts do not contain these structures (1, 13, 40).

For donor skin, the vascular bed, neural connections, and the duct portion of the sweat gland are disrupted by the harvesting procedure. This skin is placed on the wounded area where damaged skin has been removed. Thus, these grafts are entirely dependent upon blood supply and reinnervation from the recipient site. Within the first 24 h following placement of the graft, fibrin attaches the graft to the recipient bed. Anastomoses between the recipient bed and the graft are observed within 48–72 h following grafting (12, 24, 57). Revascularization and angiogenesis occur with sprouting and budding of vessels into the grafted tissue (12, 27, 57). Depending on the thickness of the graft, some degree of circulation is usually restored by the 4th to 7th day following grafting (52).

Neural control of skin blood flow is required for appropriate thermoregulatory responses; see Charkoudian (10) in this series. If the grafted areas are not appropriately revascularized and if the necessary neural connections are not reestablished, these areas of skin will not contribute to temperature regulation. Such has been proposed in a limited number of investigations of adults who had healed burns over 40% of their body, given higher rectal temperatures in these individuals during a thermal challenge relative to nonburned counterparts (5, 36, 46, 48), although this is not a consistent observation (4).

Given the importance of the skin for temperature regulation, coupled with the disruption of cutaneous vascular and neural “circuitry” in grafted skin, the purpose of this review is to highlight current findings pertaining to the consequences of skin grafting on heat-dissipating mechanisms. Prior to the authors and colleagues investigating these questions, relatively few studies in this area had been performed. Thus, in addition to highlighting findings from others, much of the presented work was conducted in a series of studies by the authors and colleagues in which individuals were assessed 5–9 mo, 2–3 yr, and 4–8 yr postgraft surgery.

Cutaneous Vasodilator and Vasoconstrictor Responses to Whole Body Heat and Cold Stress

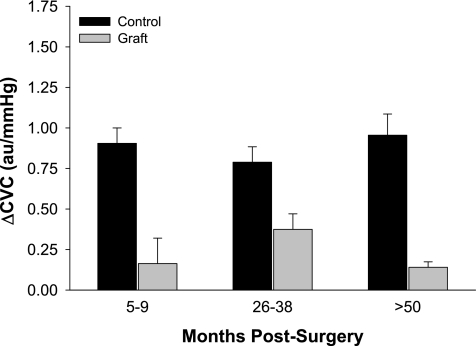

Appropriate cutaneous vasoconstrictor and vasodilator responses to cold and heat exposures, respectively, are required for humans to regulate internal temperature. These responses require intact, albeit separate, neural systems (10, 20, 21, 23, 26, 42–45, 47). Freund et al. (22) were among the first to investigate the effects of skin grafting on cutaneous vascular responses to whole body heat stress. They found that increases in skin blood flow, assessed via strain gauge plethysmography from forearms with full-thickness circumferential burns that were subsequently grafted, varied from nonexistent to relatively normal during the heat stress. Using a similar approach, but evaluated via laser-Doppler techniques, cutaneous vascular responses were investigated during a passive heat stress from both grafted and adjacent uninjured skin (see Fig. 1) (18). In both studies, the areas where skin perfusion was assessed were not in contact with the water-perfused suit used to heat the subjects (i.e., indirect whole body heating), and therefore, changes in skin blood flow from these areas were due exclusively to neurally mediated responses, not to factors associated with local heating. In contrast to the findings of Freund et al. (22), Davis et al. (18) found that in every subject the magnitude of cutaneous vasodilation at the grafted site was greatly attenuated during this heat stress, and this deficit persisted upward to ≥4 yr postgrafting surgery (Fig. 2) (17, 18). On the basis of the findings of Davis et al. (18), grafted skin is unable to appropriately increase skin blood flow during a hyperthermic challenge, with this deficit persisting for ≥4 yr postgrafting. Reasons for differences in conclusions between the findings of Freund et al. (22) and Davis et al. (18) are not forthcoming other than differences in the methodology (plethysmography vs. laser-Doppler flowmetry) used to evaluate cutaneous vascular responsiveness of the grafted skin to the heat stress.

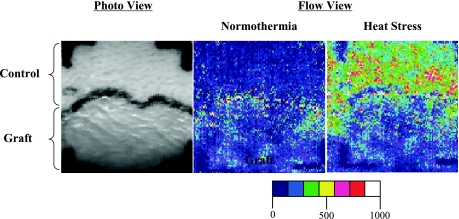

Fig. 1.

Laser-Doppler scanner images (left: photo image; right: flow images) from a representative subject during normothermia and indirect whole body heating at a grafted and adjacent control site. The black line in the middle of the photo image is the border between uninjured and grafted skin. Progressively higher skin blood flows were observed at the uninjured site during the heat stress (expressed in green, yellow, and red) compared with much lower skin blood flows in grafted skin (depicted in shades of blue). Figure modified, with permission, from Davis et al. (16).

Fig. 2.

Increases in cutaneous vascular conductance (ΔCVC) from normothermic baseline during indirect whole body heating in grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in the indicated groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. Significant main effect for skin site demonstrates attenuated vasodilator responses to indirect whole body heating at the grafted sites regardless of the duration postsurgery (P < 0.001). Figure reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

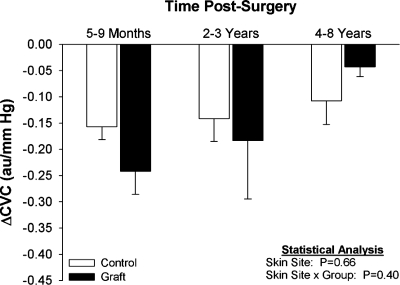

In a separate protocol, skin blood flow was similarly assessed during indirect whole body cooling (i.e., cooling the subject but not the area where skin blood flow is assessed) to identify whether neurally mediated cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses are affected by skin grafting (15). This was accomplished by perfusing 5°C water for ∼3 min through a tubed/lined suit worn by each subject. This cooling paradigm decreases mean skin temperature under the water-perfused suit from ∼34°C to typically <30°C, resulting in a decrease in skin blood flow secondary to the release of norepinephrine and cotransmitters (10, 26, 29, 53) from sympathetic adrenergic nerves innervating the skin. In order for the grafted skin to appropriately vasoconstrict during indirect whole body cooling, the grafted skin must have functional adrenergic nerves, functional α-adrenergic and related cotransmitter receptors on the cutaneous vasculature, and normal smooth muscle responses to neuronal stimulation. Skin blood flow was assessed via laser-Doppler flowmetry. Interestingly, the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction to indirect whole body cooling was not different between the grafted and control sites, and this response was unaffected by the maturity of the skin graft (Fig. 3) (15, 17). These observations suggest that grafted skin has normal vasoconstrictor capacity. On the basis of these findings, grafted skin would not impair temperature regulation during hypothermic challenges since the ability to retain heat through cutaneous vasoconstriction is generally preserved.

Fig. 3.

Decreases in ΔCVC from normothermic baseline during whole body cooling from grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in the indicated groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. Figure reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

When taken together, it is interesting to note that grafted skin apparently has normal reinnervation of the cutaneous vasoconstrictor limb but compromised reinnervation of the active vasodilator limb. Further research is warranted to identify the mechanisms responsible for this selective reinnervation following the grafting procedure.

Cutaneous Vasoconstrictor and Vasodilator Responses to Local Stimuli

Local heating and cooling.

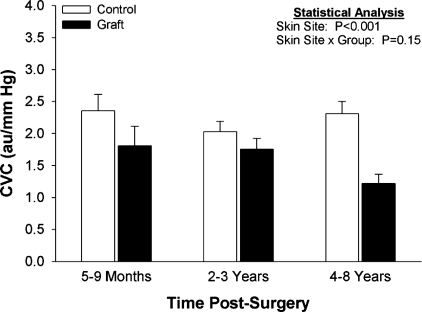

Sustained local heating (i.e., directly heating the skin where blood flow is assessed) causes pronounced cutaneous vasodilation that is primarily nitric oxide dependent (30, 34, 38). Freund et al. (22) previously suggested that skin grafting did not adversely affect cutaneous vasodilator responses to sustained whole limb local heating, although the responses were extremely variable between subjects. In a followup study, Davis and colleagues (17, 18) monitored skin blood flow via laser-Doppler flowmetry from both grafted and adjacent noninjured skin under normothermic conditions (i.e., local temperature of 34°C) and throughout 30 min of local heating at 42°C. In contrast to the findings of Freund et al. (22), the magnitude of cutaneous vasodilation to this local heating protocol was significantly less at grafted sites relative to the adjacent control sites, regardless of the maturity of the graft (Fig. 4) (17, 18). The ability to discriminate differences in skin blood flow responses via plethysmography of an entire grafted limb relative to laser-Doppler flowmetry of a smaller region is the likely rationale for the differences in conclusions between those of Freund et al. (22) and Davis and colleagues (17, 18). It is interesting to note the differences in the magnitude of vasodilation at the grafted skin sites between whole body heating and local heating stimuli (see gray bars in Fig. 2 and black bars in Fig. 4). Although local heating-induced vasodilation is significantly impaired in grafted skin, the magnitude of vasodilation to this stimulus was profoundly greater than the dilation that occurred during whole body heating, when the assessed sites were not directly exposed to the heating stimulus. Thus grafted skin retains, to a greater extent, the capacity to dilate to a local heating stimulus relative to a whole body heating stimulus. A rationale for this large difference in cutaneous vasodilation in grafted tissue between these heating stimuli is likely related to the differing mechanisms by which the skin dilates upon increases in local vs. core temperatures (10, 25).

Fig. 4.

Increases in CVC during local heating in grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in the indicated groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. Significant main effect for skin site demonstrates attenuated vasodilator responses to local heating at the grafted sites regardless of the duration postsurgery (P < 0.001). Figure reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

To evaluate the effects of skin grafting on cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses to local cooling, skin blood flow was evaluated over both grafted and adjacent uninjured skin during cooling from local temperatures of 39 to 19°C. This was accomplished using a Peltier cooling device that housed the laser-Doppler flow probe. Similar to that observed during the whole body cooling perturbation, the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction to the local cooling perturbation was not different between sites regardless of the maturity of the graft (15).

Endothelial-dependent and -independent cutaneous vasodilation.

Attenuated vasodilator responses of grafted skin to sustained local heating as well as whole body heating could be due, in part, to alterations in nitric oxide release and/or impaired vascular responsiveness to nitric oxide. Both possibilities are intriguing given that ∼30% of the cutaneous active vasodilator response during whole body heating is nitric oxide dependent (28), and cutaneous vasodilation to sustained local heating occurs primarily via endothelial-dependent nitric oxide release (30, 31, 34, 38). Given these observations, Davis and colleagues (16, 17) sought to identify whether skin grafting impairs endothelial-dependent and -independent cutaneous vasodilation. To accomplish these objectives, intradermal microdialysis probes were placed in grafted and adjacent uninjured skin (Fig. 5), with these probes being perfused with increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (endothelial-dependent vasodilator), and at separate sites increasing concentrations of sodium nitroprusside (nitric oxide donor resulting in endothelial-independent vasodilation). Skin blood flow was measured over the membrane portion of each probe, and dose-response curves were constructed. The primary variables that were evaluated were the effective concentration resulting in 50% of the maximal vasodilator response (i.e., EC50) as well as the maximal vasodilator response to these agents. The maximal increase in skin blood flow due to acetylcholine administration was significantly lower at grafted sites regardless of graft maturity (Table 1) (16, 17). The EC50 of the dose-response curve from grafted sites was significantly greater relative to uninjured sites, indicative of a rightward shift of the curve representative of a decreased sensitivity of the vasodilator response to acetylcholine. Conversely, maximal cutaneous vasodilator responsiveness, as well as the EC50 of the dose-response curves, to sodium nitroprusside was not different between uninjured and grafted sites (Table 2) (17). Neither of these responses was affected by the duration postgraft surgery. On the basis of these collective findings, attenuated vasodilator responsiveness to the aforementioned sustained local heating perturbation could be due to altered nitric oxide release presumably from endothelial sources (32). Altered nitric oxide release may also partially explain the attenuated vasodilator responsiveness during whole body heating in grafted skin (17, 18), given that ∼30% of cutaneous vasodilation during such a heat stress is nitric oxide dependent (28, 49, 50). However, attenuated nitric oxide release alone is unlikely to account entirely for decreases in cutaneous vasodilation in grafted skin during the whole body heat stress, given that the magnitude of cutaneous vasodilation at the grafted sites during whole body heating was ∼75% attenuated relative to that observed in uninjured skin (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

Top: illustration of the placement of the microdialysis probes in uninjured and grafted skin as well as a schematic of the principle of intradermal microdialysis. Substances in the perfusate diffuse through the semipermeable portion of the probe and exert an effect in the surrounding tissue. Bottom: cutaneous vascular responses, expressed as CVC, to the indicated doses of acetylcholine (Ach) administered via intradermal microdialysis in the 5- to 9-mo postgraft group. Values are expressed as means ± SE. From these data the effective concentration causing 50% of the maximal response and the maximal responses are calculated. Bottom part of figure reprinted from Davis et al. (16) with permission.

Table 1.

Modeled maximum CVC responses and the effective concentration causing 50% of the maximum response (EC50) generated from acetylcholine dose-response curves in grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in groups 5–9 mo postsurgery, 2–3 yr postsurgery, and 4–8 yr postsurgery

| Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 5–9 mo (n = 12) | 2–3 yr (n = 11) | 4–8 yr (n = 12) | Analysis |

| Maximum CVC, AU/mmHg | ||||

| Control | 1.34 ± 0.15 | 1.46 ± 0.21 | 1.19 ± 0.19 | Skin site: P < 0.001 |

| Graft | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | Skin site × group: P = 0.74 |

| EC50 (log M drug dose) | ||||

| Control | −3.59 ± 0.19 | −3.72 ± 0.17 | −2.89 ± 0.22 | Skin site: P < 0.001 |

| Graft | −2.61 ± 0.15 | −2.99 ± 0.19 | −2.77 ± 0.24 | Skin site × group: P = 0.08 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. CVC, cutaneous vascular conductance; AU, arbitrary units. Table reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

Table 2.

Modeled maximum CVC responses and the EC50 generated from sodium nitroprusside dose-response curves in grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in groups 5–9 mo postsurgery, 2–3 yr postsurgery, and 4–8 yr postsurgery

| Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 5–9 mo (n = 12) | 2–3 yr (n = 11) | 4–8 yr (n = 12) | Analysis |

| Maximum CVC, AU/mmHg | ||||

| Control | 1.46 ± 0.12 | 1.78 ± 0.21 | 1.42 ± 0.18 | Skin site: P = 0.17 |

| Graft | 0.99 ± 0.20 | 1.08 ± 0.11 | 0.81 ± 0.16 | Skin site × group: P = 0.78 |

| EC50 (log M drug dose) | ||||

| Control | −3.87 ± 0.19 | −4.29 ± 0.17 | −4.40 ± 0.18 | Skin site: P = 0.65 |

| Graft | −4.21 ± 0.27 | −4.13 ± 0.20 | −4.00 ± 0.24 | Skin site × group: P = 0.21 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Table reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

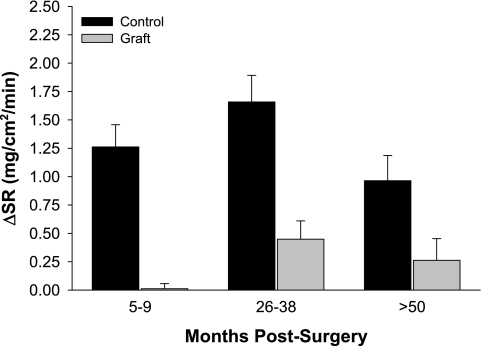

Sweating Responses to Both Central and Peripheral Stimuli

Although sweating responses may be normal in full-thickness skin grafts (13, 33, 36, 37, 40), most studies show an absence of sweating from split-thickness grafts (13, 33, 36, 37, 40), although one of those studies reported normal sweating from some grafts (40). The reported lack of sweating in split-thickness skin grafts is thought to be due to a combination of the initial injury damaging sweat glands at the recipient site and the harvested skin taken from donor sites not containing sweat glands (1). However, the potential contribution of denervation of the sweat gland in causing an absence of sweating from grafted skin (13, 33, 36, 37, 40) had not been investigated, nor was it known whether sweat glands regenerate in split-thickness grafted tissue as the graft matures. To address this deficit, studies were performed to identify postsynaptic sweat gland responsiveness in grafted skin as well as to evaluate whether grafted skin has the capacity to regain sweating responses to central and peripheral stimuli as the graft matures (17, 18). To evaluate the effects of skin grafting on centrally driven sudomotor responses in the grafted area, sweat rate was measured via capacitance hygrometry from grafted and adjacent uninjured areas of skin during an indirect whole body heat stress. Similar to the observation of Ponten (40), two subjects in each of the 2- to 3-yr and the 4- to 8-yr postsurgery groups exhibited slight sweating in the grafted skin, although the magnitude of sweating at these sites was less than at the adjacent control sites. The remaining subjects in these groups, as well as all subjects in the 5- to 9-mo postgraft group, showed minimal or no sweating from grafted sites (17, 18). The statistical analysis revealed that sweat rate was significantly reduced at the grafted site, and the magnitude of this attenuation was not different when compared between graft maturities (Fig. 6). These data support the hypothesis that sweating responses to a whole body heat stress remain disrupted as the graft matures.

Fig. 6.

Changes in sweat rate (ΔSR) from normothermic baseline during whole body heating from grafted (graft) and adjacent noninjured (control) skin in the indicated groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. Significant main effect for skin site demonstrates attenuated sweating responses to whole body heating at the grafted sites regardless of the duration postsurgery (P < 0.001). Figure reprinted from Davis et al. (17) with permission.

Based solely upon the findings in Fig. 6, it is unknown whether reduced sweating responses were due to an absence of functional sweat glands or to disrupted innervation of the sweat gland. One way to address this question is to evaluate sweating responses to a peripheral stimulus, such as exogenous administration of acetylcholine, which stimulates sweating in a dose-dependent manner (14, 51). Thus, the second aim was accomplished upon administration of increasing doses of acetylcholine (1 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−1 M at 10-fold increments) via intradermal microdialysis in grafted and adjacent uninjured grafted skin (16, 17). Sweat rate was measured directly above the microdialysis membranes via capacitance hygrometry. The intent was to model these data via nonlinear regression techniques to identify the EC50 of the response, similar to the analysis done for skin blood flow. However, this modeling could not be performed due to the absence of sweating at skin graft sites, regardless of the dose of acetylcholine. These data suggest that sweating responsiveness is impaired in skin grafts, likely due to a reduction or absence of functional sweat glands in the grafted tissue, and that sweating responsiveness shows little evidence of normalizing as the graft matures (16, 17).

Cutaneous Vasomotor and Sweating at Donor Sites

Reduced vasomotor and sweating responses from donor skin may contribute to impaired thermoregulatory responses in skin graft patients who undergo autografting procedures. The harvesting procedure removes the entire epidermal layer and some of the dermal layer from the donor site and thus may alter cutaneous vasodilator and sweating responsiveness at that site. To that end, cutaneous vasomotor and sudomotor responses at donor sites were assessed during indirect whole body heat stress across all groups. Counter to that observed at the grafted sites, normal cutaneous vasodilation and sweating were observed at the donor sites during the heat stress across all maturities (17, 18). These data strongly suggest that the size of the area of skin harvested from donor sites will not adversely affect temperature regulation in skin graft patients.

Perspectives

Given impaired heat-dissipating responses in grafted skin, one may ask the following questions. 1) How much noninjured skin is required for an individual to appropriately regulate internal temperature during a hyperthermic challenge (i.e., via exercise and/or exposure to elevated environmental conditions), and 2) in the face of impaired cutaneous vasodilation and sweating of grafted tissue, does noninjured skin have the capacity to compensate for reduced vasodilatory and sweating responses of the grafted skin? Only a few studies have investigated the first question in adults (4, 46, 48), resulting in mixed findings due primarily to methodological limitations and small numbers of subjects (as little as 2 subjects/group). Thus, the percentage of BSA of grafted skin resulting in impaired tolerance to a hyperthermic challenge remains unclear, requiring carefully controlled studies with adequate statistical power to address this important question. A few studies have investigated the first question in children (35, 36, 39). However, given large differences in surface-to-mass ratios between adults and children, and the implications of such with respect to exercise and temperature control (7, 54), thermoregulatory responses in children with skin grafts may be different from adults. With respect to the second question, Brengelmann (6) proposed the following relatively simple formula to describe heat transfer from the body core to the environment: Ht = At × Kt (Tc − Tsk), where heat transfer (Ht) is a function of BSA available to transfer heat (At), skin blood flow (Kt), and the temperature gradient (i.e., difference) between the core and the skin (Tc − Tsk). From this equation, and based upon the presented findings, one could presume that since skin graft patients have reduced BSA for heat exchange (At) they would have reduced Ht, thereby impairing temperature regulation. However, this conclusion ignores the possibility for the other variables in the equation [i.e., Kt and/or (Tc − Tsk)] to compensate for the reduction in functional BSA for heat exchange (At). For example, if noninjured skin blood flow is higher (elevated Kt) and/or if sweat rate is higher, resulting in lower Tsk (i.e., elevated core to skin temperature gradient variable; Tc − Tsk) during a heat stress, then it is conceivable that Ht could approach normal levels in these patients despite a reduction in available BSA (At) for Ht. Thus, the capacity for an individual with a large percentage of BSA of grafted skin to thermoregulate will be based not only upon the amount of skin that is grafted but also the degree to which the noninjured skin can compensate through greater increases in skin blood flow and sweating. Consistent with the aforementioned hypothesis, investigators found higher whole body sweat rates in some burned patients relative to control (i.e., nonburned) subjects (4, 48) despite reduced BSA for sweating in the graft patients. The investigators proposed that the normal skin of burned patients may have the capacity to compensate for deficits in thermoregulatory capabilities of burned skin. Whether this is the case remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

Summary

The initial injury and subsequent grafting procedures profoundly affect the capacity for grafted skin to dissipate heat through cutaneous vasodilation and sweating. Based upon prevailing evidence, this deficit persists for >4 yr following the grafted procedure and is perhaps permanently disrupted. If uninjured skin cannot adequately compensate for the lack of heat dissipation of the grafted skin, individuals with skin grafts covering large percentages of their BSA will be at a greater risk for a heat-related injury. Conversely, the capacity for grafted skin to vasoconstrict to both a central stimulus (i.e., indirect whole body cooling) as well as a peripheral stimulus (i.e., local cooling) is retained as early as 5–9 mo postgrafting. These data suggest that grafted skin retains its capacity to conserve heat through vasoconstriction to a cold stimulus, and thus individuals with grafted skin are unlikely to be at a greater risk for hypothermia upon exposure to cold environmental conditions.

GRANTS

The presented work that was conducted by the authors was funded by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences: GM-068865 and GM-071092.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to the following collaborators who assisted with our studies contained herein: Drs. Brett Arnoldo, Jian Cui, Vincent Gabriel, John Hunt, Karen Kowalske, David Keller, David Low, Gary Purdue, and Manabu Shibasaki.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ablove RH, Howell RM. The physiology and technique of skin grafting. Hand Clin 13: 163–173, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Burn Association American Burn Association National Burn Repository (2006 Report). Chicago, IL: American Burn Association, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anonymous Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1996. Washington, DC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Austin KG, Hansbrough JF, Dore C, Noordenbos J, Buono MJ. Thermoregulation in burn patients during exercise. J Burn Care Rehabil 24: 9–14, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ben-Simchon C, Tsur H, Keren G, Epstein Y, Shapiro Y. Heat tolerance in patients with extensive healed burns. Plast Reconstr Surg 67: 499–504, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brengelmann GL. Body temperature regulation. In: Textbook of Physiology, edited by Patton HD, Fuchs AF, Hille B, Scher AM, Steiner R. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders, 1989, p. 1584–1596 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bytomski JR, Squire DL. Heat illness in children. Curr Sports Med Rep 2: 320–324, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cancio LC, Horvath EE, Barillo DJ, Kopchinski BJ, Charter KR, Montalvo AE, Buescher TM, Brengman ML, Brandt MM, Holcomb JB. Burn support for Operation Iraqi Freedom and related operations, 2003 to 2004. J Burn Care Rehabil 26: 151–161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CDC Mass Casualities: Burn. In: Injury Fact Sheets 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charkoudian N. Mechanisms and modifiers of reflex induced cutaneous vasodilation and vasoconstriction in humans. J Appl Physiol. First published May 6, 2010; doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00298.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chung KK, Blackbourne LH, Wolf SE, White CE, Renz EM, Cancio LC, Holcomb JB, Barillo DJ. Evolution of burn resuscitation in operation Iraqi freedom. J Burn Care Res 27: 606–611, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clemmesen T, Ronhovde DA. Restoration of blood supply to human skin autografts. Scand J Plast Reconstr 2: 44–46, 1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conway H. Sweating function in transplanted skin. Gynec & Obst 69: 756–761, 1939 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crandall CG, Shibasaki M, Wilson TE, Cui J, Levine BD. Prolonged head-down tilt exposure reduces maximal cutaneous vasodilator and sweating capacity in humans. J Appl Physiol 94: 2330–2336, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, Cui J, Keller DM, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, Kowalske KJ, Crandall CG. Cutaneous vasoconstriction during whole-body and local cooling in grafted skin five to nine months postsurgery. J Burn Care Res 29: 36–41, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, Cui J, Keller DM, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, Kowalske KJ, Crandall CG. Skin grafting impairs postsynaptic cutaneous vasodilator and sweating responses. J Burn Care Res 28: 435–441, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, Cui J, Keller DM, Wingo JE, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, Kowalske KJ, Crandall CG. Sustained impairments in cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in grafted skin following long-term recovery. J Burn Care Res 30: 675–685, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, Cui J, Keller DM, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, Arnoldo TB, Kowalske KJ, Crandall CG. Impaired cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in grafted skin during whole-body heating. J Burn Care Res 28: 427–434, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edholm OG, Fox RH, MacPherson RK. The effect of body heating on the circulation in skin and muscle. J Physiol 134: 612–619, 1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edholm OG, Fox RH, Macpherson RK. Vasomotor control of the cutaneous blood vessels in the human forearm. J Physiol 139: 455–465, 1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freund PR, Brengelmann GL, Rowell LB, Engrav L, Heimbach DM. Vasomotor control in healed grafted skin in humans. J Appl Physiol 51: 168–171, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grant RT, Holling HE. Further observations on the vascular responses of the human limb to body warming; evidence for sympathetic vasodilator nerves in the normal subject. Clin Sci (Lond) 3: 273–285, 1938 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Henry L, Marshall DC, Friedman EA, Goldstein DP, Dammin GJ. A histological study of the human skin graft. Am J Pathol 39: 317–332, 1961 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson JM, Kellogg DL., Jr Local thermal control of the human cutaneous circulation. J Appl Physiol. First published June 3, 2010; doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00407.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson JM, Proppe DW. Cardiovascular adjustments to heat stress. In: Handbook of Physiology. Environmental Physiology, edited by Fregly MJ, Blatteis CM. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1996, sect. 4, vol. II, chapt. 11, p. 215–243 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson TM, Ratner D, Nelson BR. Soft tissue reconstruction with skin grafting. J Am Acad Dermatol 27: 151–165, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kellogg DL, Jr, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 824–829, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kellogg DL, Jr, Johnson JM, Kosiba WA. Selective abolition of adrenergic vasoconstrictor responses in skin by local iontophoresis of bretylium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H1599–H1606, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kellogg DL, Jr, Liu Y, Kosiba IF, O'Donnell D. Role of nitric oxide in the vasculature effects of local warming of the skin in humans. J Appl Physiol 86: 1185–1190, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kellogg DL, Jr, Zhao JL, Wu Y. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase control mechanisms in the cutaneous vasculature of humans in vivo. J Physiol 586: 847–857, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kellogg DL, Jr, Zhao JL, Wu Y. Roles of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in cutaneous vasodilation induced by local warming of the skin and whole body heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol 107: 1438–1444, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Löfgren L. Recovery of nervous function in skin transplant with special reference to the sympathetic functions. Acta Chir Scand 102: 229–239, 1952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Low DA, Shibasaki M, Davis SL, Keller DM, Crandall CG. Does local heating-induced nitric oxide production attenuate vasoconstrictor responsiveness to lower body negative pressure in human skin? J Appl Physiol 102: 1839–1843, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McEntire SJ, Herndon DN, Sanford AP, Suman OE. Thermoregulation during exercise in severely burned children. Pediatr Rehabil 9: 57–64, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGibbon B, Beaumont WV, Strand J, Paletta FX. Thermal regulation in patients after the healing of large deep burns. Plast Reconstr Surg 52: 164–170, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McGregor IA. The regeneration of sympathetic activity in grafted skin as evidenced by sweating. Br J Plast Surg 3: 12–27, 1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Minson CT, Berry LT, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. J Appl Physiol 91: 1619–1626, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mlcak RP, Desai MH, Robinson E, McCauley RL, Robson MC, Herndon DN. Temperature changes during exercise stress testing in children with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 14: 427–430, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ponten B. Grafted skin. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 257: 1–78, 1960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pruitt BA, Wolf SE, Mason AD. Epidemiological, demongraphic, and outcome characteristics of burn injury. In: Total Burn Care, edited by Herndon DN. St. Louis, MO: Saunders, 2007, p. 14–32 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roddie IC. Circulation to skin and adipose tissue. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Cardiovascular System, edited by Shepherd JT, Abboud FM. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1983, sect. 2, vol. III, chapt. 10, p 285–317 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roddie IC. Sympathetic vasodilatation in human skin. J Physiol 548: 336–337, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roddie IC, Shepherd JT, Whelan RF. The contribution of constrictor and dilator nerves to the skin vasodilatation during body heating. J Physiol 136: 489–497, 1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roddie IC, Shepherd JT, Whelan RF. The vasomotor nerve supply to the skin and muscle of the human forearm. Clin Sci (Lond) 16: 67–74, 1956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roskind JL, Petrofsky J, Lind AR, Paletta FX. Quantitation of thermoregulatory impairment in patients with healed burns. Ann Plast Surg 1: 172–176, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rowell LB. Thermal stress. In: Human Circulation Regulation During Physical Stress. New York: Oxford University, 1986, p. 174–212 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shapiro Y, Epstein Y, Ben-Simchon C, Tsur H. Thermoregulatory responses of patients with extensive healed burns. J Appl Physiol 53: 1019–1022, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shastry S, Dietz NM, Halliwill JR, Reed AS, Joyner MJ. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on cutaneous vasodilation during body heating in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 830–834, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shastry S, Minson CT, Wilson SA, Dietz NM, Joyner MJ. Effects of atropine and l-NAME on cutaneous blood flow during body heating in humans. J Appl Physiol 88: 467–472, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shibasaki M, Crandall CG. Effect of local acetylcholinesterase inhibition on sweat rate in humans. J Appl Physiol 90: 757–762, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smahel J. The healing of skin grafts. Clin Plast Surg 4: 409–424, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stephens DP, Aoki K, Kosiba WA, Johnson JM. Nonnoradrenergic mechanism of reflex cutaneous vasoconstriction in men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1496–H1504, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tsuzuki-Hayakawa K, Tochihara Y, Ohnaka T. Thermoregulation during heat exposure of young children compared to their mothers. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 72: 12–17, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Utah Department of Health Work-Related Burn Surveillance in Utah, 2001. Office of Epidemiology, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wolf SE, Kauvar DS, Wade CE, Cancio LC, Renz EP, Horvath EE, White CE, Park MS, Wanek S, Albrecht MA, Blackbourne LH, Barillo DJ, Holcomb JB. Comparison between civilian burns and combat burns from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. Ann Surg 243: 786–792; discussion 792–795, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zarem HA, Zweifach BW, McGehee JM. Development of microcirculation in full thickness autogenous skin grafts in mice. Am J Physiol 212: 1081–1085, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]