Abstract

The prevalence of diabetic nephropathy continues to rise, highlighting the importance of investigating and discovering novel treatment strategies. TRB3 is a kinase-like molecule that modifies cellular survival and metabolism and interferes with signal transduction pathways. Herein, we report that TRB3 expression is increased in the kidneys of type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice. TRB3 is expressed in conditionally immortalized podocytes; however, it is not stimulated by elevated glucose. The diabetic milieu is associated with increased oxidative stress and circulating free fatty acids (FFA). We show that reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2 and superoxide anion (via the xanthine/xanthine oxidase reaction) as well as the FFA palmitate augment TRB3 expression in podocytes. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) is a transcription factor that is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. CHOP expression increases in diabetic mouse kidneys and in podocytes treated with ROS and FFA. In podocytes, transfection of CHOP increases TRB3 expression, and ROS augment recruitment of CHOP to the proximal TRB3 promoter. MCP-1/CCL2 is a chemokine that contributes to the inflammatory injury associated with diabetic nephropathy. In these studies, we demonstrate that TRB3 can inhibit basal and stimulated podocyte production of MCP-1. In summary, enhanced ROS and/or FFA associated with the diabetic milieu induce podocyte CHOP and TRB3 expression. Because TRB3 inhibits MCP-1, manipulation of TRB3 expression could provide a novel therapeutic approach in diabetic kidney disease.

Keywords: diabetic nephropathy, free fatty acids

the prevalence of diabetes is reaching epidemic levels and projections suggest that there will be 44 million diabetics in the United States by 2034 (17). Approximately 30–40% of these patients will develop diabetic nephropathy; therefore, it will be imperative to develop new strategies and novel molecular approaches to slow the progression of this devastating disease.

Podocytes are highly specialized glomerular epithelial cells that play a vital role in glomerular filtration (37), and diabetic kidney disease is associated with podocyte loss and defective podocyte function (26). In diabetes, the mediators of podocyte injury include reactive oxygen species (ROS), angiotensin II (ANG II), matrix metalloproteinases, prostaglandins, mechanical stretch, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (50). Work over the last several decades has revealed that kidney injury induces morphological changes in podocytes and upregulation of lymphocyte and antigen presenting cell (APC) markers including CD68 (3), MHC-II, ICAM-1 (8), and B7–1 (41).

Our previous work showed that the anti-inflammatory effects of PPAR-α ligands are related to expression of a novel protein known as TRB3 (31, 48). Evidence suggests that TRB3 may function as a scaffold protein to dampen potentially injurious signaling cascades, including AKT/protein kinase B and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (22).

There are three TRB family members (TRB1, TRB2, and TRB3). TRB2 is expressed in the metanephric mesenchyme and localized in the podocytes (55); however, conditional knockout of TRB2 does not alter murine kidney development (54). In renal transplants, TRB1 expression increases in the APCs in the blood and kidneys of patients with chronic antibody-mediated rejection (2). The relevance of TRB3 expression in the kidney has not been assessed.

MCP-1 also known as “chemokine ligand 2” (CCL2) attracts and activates monocytes and macrophages. Podocytes are an important source of MCP-1 (6, 7, 16) and MCP-1 induces podocyte proliferation, migration (6), and reduces nephrin expression (57). MCP-1 plays a central role in promoting renal injury and blockade of MCP-1 improves the manifestations of inflammatory diseases including diabetic nephropathy and atherosclerosis (review in Ref. 21). Thus, current efforts are focused on finding therapeutic blockers of MCP-1 activity.

Here, we demonstrate for the first time that TRB3 expression is upregulated in murine diabetic kidneys. We discovered that conditionally immortalized podocytes express TRB3, but interestingly, high-glucose conditions do not regulate TRB3 expression. In podocytes, TRB3 is upregulated by ROS as well as the free fatty acid (FFA) palmitate, both of which are enhanced in the kidneys and circulation of patients with type 2 diabetes. Additionally, we demonstrate that C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), a marker of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, increases in murine diabetic kidneys. In podocytes, ROS and FFA enhance CHOP mRNA and protein expression and increase binding of CHOP to the TRB3 promoter. Finally, we show for the first time that TRB3 inhibits podocyte expression of MCP-1, suggesting that TRB3 may be protective in diabetic kidney disease.

METHODS

Diabetic mouse models.

Mice were housed and handled in accordance with Veterans Affairs and National Institutes of Health guidelines under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols. Type 1 diabetes was induced in 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice by low-dose streptozotocin (STZ) injection (50 mg/kg × 5 days). Hyperglycemia was confirmed in the diabetic mice (STZ treatment: blood glucoses > 350 mg/dl) and mice were euthanized 8 wk after induction of type 1 diabetes.

For the model of type 2 diabetes, we used five db/db: BKS.Cg-Dock7m +/+ Leprdb/J (stock number 642) obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) and five db/m nondiabetic, lean heterozygote littermates.

Immunofluorescence studies.

Frozen sections (10 μm) of control and STZ-treated mouse kidneys were stained with antibodies to TRB3 (1:400; Marc Montminy), podocin [1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SCBT), Santa Cruz, CA], anti-rabbit Cy3 and anti-goat Alexa fluor 488 (1:400; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) and mounted with Prolong Gold. The sections were visualized with an Olympus IX81 inverted spinning disk confocal microscope with Slidebook 4.1. Frozen sections (5 μm) of db/m and db/db mice were stained with TRB3 (1:200), podocin (1:200), anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 488 (1:400), and anti-goat Alexa fluor 594 (1:400) and visualized with a Zeiss LSM 510 laser-scanning confocal microscope.

Podocytes.

Conditionally immortalized podocytes were kindly provided by Dr. P. Mundel and Dr. S. Shankland and propagated at 33°C (permissive conditions) on type I collagen-coated plastic plates with IFN-γ as previously described (51). For differentiation, cells were transferred to 37°C for 14 days and semiquantitative PCR studies were used to verify expression of synaptopodin (Table 1).

Table 1.

PCR primers used

| Target | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Synaptopodin | GTCAAGGAACCTGCCAAGG | AGAAGGAAGGCCTGGGAG |

| Chop | AGGAGCCAGGGCCAACA | TGACTGGAATCTGGAGAGCGA |

| Rpl19 | TGCTCAGGCTACAGAAGAGGCTTG | GGAGTTGGCATTGGCGATTTC |

| ChlP (prox) | GGGCGTGTGGCCCCGAAG | GGATCCCCGCCCGGCTGAT |

| TRB3 cloning | TGAGGCCGGGATCCCGGATGCGAGCT | GGGGCCAGTGCTCTAGAGCTAGCCGTACAG |

Real-time PCR.

RNA, cDNA, and real-time PCR studies were performed as previously described (1). For quantification of TRB3, we used TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (TRB3: Mm00454879_m1; TRB1: Mm00454875_m1; TRB2: Mm00454876_m1). Amplification efficiencies were normalized against RPL19 (Table 1) and relative fold increases were calculated using the Pfaffl technique of relative quantification (38). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and at least three times.

Western blotting.

Cellular lysates were prepared with Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) with protease inhibitors (31). Samples were run on NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The following antibodies were used: TRB3 (1:400; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), CHOP/GADD153 (1:400; SC-793, SCBT), actin (1:400; SC-1616, SCBT) and detection was performed with ECL Plus Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Palmitate-BSA preparation.

Fatty acid and endotoxin-free BSA (5.5 g; Sigma, no. A8806) were added to 50 ml of Krebs Ringer bicarbonate buffer. Palmitate (10 mM final; Sigma) was prepared in 1 ml of ethanol and then added to the BSA under nitrogen. Samples were filter sterilized and concentrations were assayed using the NEFA-HR kit (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA). In the same manner, the BSA control was prepared with ethanol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Fully differentiated podocytes were treated with 50 μM H202 or control for 4 h and then harvested with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies were performed per the manufacturer's instructions (EZ ChIP, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and as previously described (48). Immunoprecipitation was performed with 4 μg of the following antibodies: CHOP/GADD153 (SC-793), C/EBPβ (SC-150X), and anti-rabbit IgG (SCBT) at 4°C. DNA was purified and PCR was performed with primers corresponding to the proximal CHOP/C/EBPβ binding site 61 bp from the TRB3 transcription start site (ChIP prox; Table 1).

Plasmids and transient transfections.

A TRB3 expression plasmid was generated as previously described, pcDNA3-HA-TRB3 (31). A CHOP plasmid was amplified from mCHOP10.pcDNA1 (David Ron Lab) and cloned into pcDNA3. Fully differentiated podocytes (14 days at 37°C) were removed from 10-cm plates with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA) and replated and transfected in 96-well plates (∼9 × 104 cells/well) with 100 μl Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and 1.5 μl/well Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using 750 ng/well of pcDNA3-HA-TRB3 and its control pcDNA3. For the MCP-1 studies, cells were stimulated with 20 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and after 24 h MCP-1 expression was determined with the BD OptEIA ELISA Kit (BD Pharmingen). For the CHOP and TRB3 transfection, cells were replated in 12-well plates with 2.5 μg of pcDNA3, pcDNA3-CHOP, or pcDNA3-HA-TRB3, 7 μl/well of Lipofectamine 2000 in 1 ml of Opti-MEM. Cells were harvested after 24 h and Western blotting was performed.

Statistics.

Differences were analyzed using the Student's t-test, ANOVAs with post hoc Tukey tests for pair-wise comparisons. Analysis was accomplished with SPSS 11 (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

TRB3 expression increases in diabetic kidneys.

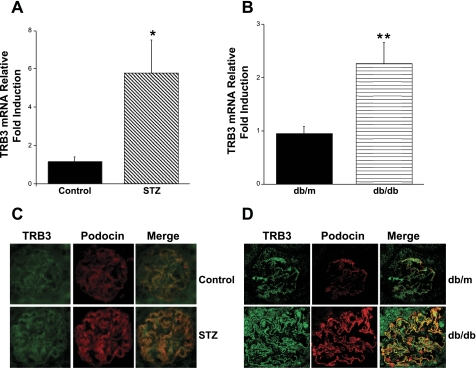

Diabetes was induced in 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice by low-dose STZ injection. Control mice received vehicle (citrate buffer). Hyperglycemia was confirmed in the diabetic mice and mice were euthanized 8 wk after induction of type 1 diabetes. Figure 1A demonstrates that there was a fivefold increase in TRB3 mRNA expression in the diabetic kidneys compared with the controls. TRB1 and TRB2 mRNA expression were not increased in the diabetic kidneys (data not shown). Expression of TRB3 mRNA was also significantly increased in 24-wk-old db/db mice compared with db/m controls (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence studies confirmed that there was upregulation of TRB3 protein expression in the glomeruli of the STZ-treated and db/db mice when compared with the control and db/m mice (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

TRB3 expression increases in diabetic mouse kidneys. A: C57BL/6 mice were treated with low-dose streptozotocin (STZ) and kidneys were harvested 8 wk later. Real-time PCR studies revealed a 5-fold increase in TRB3 expression in the STZ-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group). B: TRB3 expression was also increased in the kidneys of 24-wk-old db/db mice (n = 5 mice per group). *P < 0.05 vs. control mice, **P < 0.05 vs. db/m mice, Student's t-test and bars represent SE. Frozen sections of control and STZ-treated (×600) mice (C) and db/m and db/db (×1,000) mice (D) were stained with anti-TRB3 and anti-podocin. There is an upregulation of TRB3 staining in the glomeruli of the diabetic mice (STZ, db/db) when compared with the controls (control, db/m).

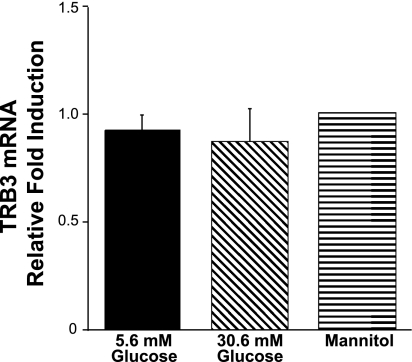

Podocytes express TRB3, and high glucose does not augment expression of TRB3.

Conditionally immortalized murine podocytes express TRB3 (Fig. 2). During their differentiation, murine podocytes were incubated for 10 days in normal (5.6 mM glucose)- and high-glucose (30.6 mM glucose) conditions. Cells were also incubated in mannitol to control for the osmolarity. There were no significant changes in TRB3 expression in any of the conditions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

High-glucose conditions do not regulate TRB3 expression. Conditionally immortalized podocytes were differentiated and incubated for 14 days in high-glucose conditions. Mannitol was used as an osmotic control. The results are the average of 3 studies performed.

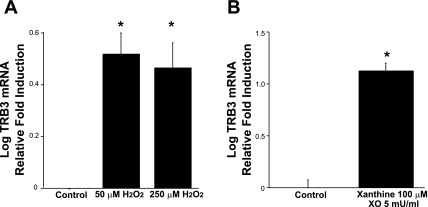

Podocyte TRB3 expression is induced by ROS.

It is generally accepted that the pathogenesis underlying diabetic kidney disease is due in part to the generation of ROS (24). Thus, we tested the hypothesis that ROS enhance expression of TRB3. Indeed, TRB3 mRNA expression was increased in conditionally immortalized, fully differentiated podocytes treated for 4 h with H2O2 (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we investigated whether other ROS generators such as the xanthine/xanthine oxidase (XO) reaction augment TRB3 expression. Conditionally immortalized and differentiated podocytes were treated for 3 h with 100 μM xanthine and 5 mU/ml XO and similar to H2O2, the xanthine/XO reaction augmented TRB3 expression (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) augment TRB3 expression. Fully differentiated, conditionally immortalized podocytes were treated for 4 h with H2O2 (A) and 3 h with xanthine and xanthine oxidase (B). Real-time PCR demonstrated that ROS augment TRB3 mRNA expression. Each study was performed at least 3 times and the averages of the results are shown. *P < 0.05 vs. control mice; 1-way ANOVA (A) and Student's t-test (B).

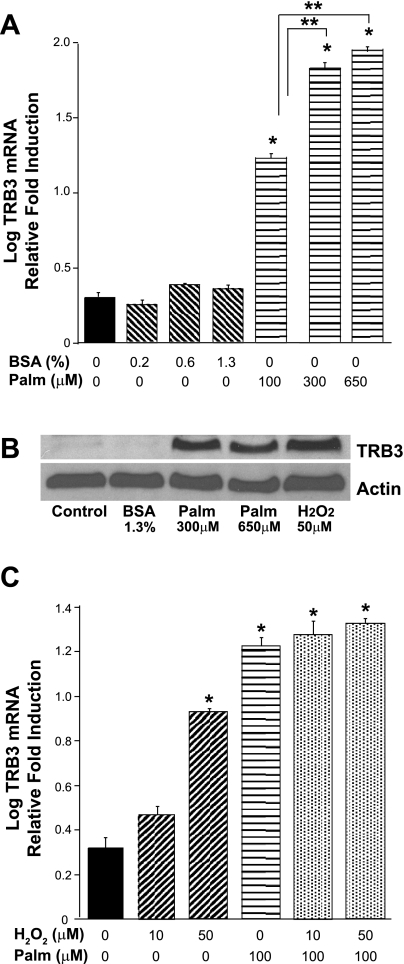

FFA augment TRB3 expression.

Many research groups showed that oxidative stress associated with diabetes is due to hyperglycemia (11, 24, 42). However, in our podocyte studies, high-glucose conditions did not augment TRB3 expression. Early in diabetes, before the development of hyperglycemia, FFA can induce the production of ROS (12, 30). Since palmitate is the most abundant FFA in the plasma, we tested whether palmitate induces TRB3 expression. Palmitate potently increased TRB3 mRNA levels in podocytes (Fig. 4A). Palmitate circulates in the blood bound to albumin, therefore BSA was used to control for the amounts of BSA bound to palmitate (1.3% BSA is the control for 650 μM palmitate). BSA did not appear to regulate TRB3 expression. Importantly, Fig. 4B confirms that FFA and ROS also increase podocyte TRB3 protein expression. However, ROS and palmitate do not appear to have additive effects on TRB3 expression (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Free fatty acids (FFA) increase TRB3 expression. Fully differentiated, conditionally immortalized podocytes were treated for 24 h with graded concentrations of palmitate:BSA and BSA controls. A: real-time PCR studies demonstrated that FFA induce TRB3 expression. *P < 0.05 vs. control, **P < 0.05 vs. 100 μM palmitate. B: fully differentiated podocytes were treated with palmitate, BSA, and H2O2 overnight. Cellular lysates were harvested and Western blotting was performed and blotted for TRB3 and actin. The following blot is representative of studies performed at least 3 times. C: palmitate and H2O2 were added simultaneously and separately and do not appear to have an additive effect on TRB3 expression. *P < 0.05 vs. control (BSA, 1-way ANOVA).

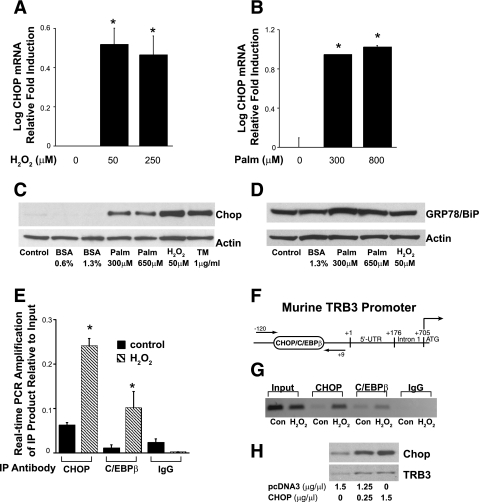

ROS and FFA induce expression of CHOP in podocytes and recruitment of CHOP to the TRB3 promoter.

Our next goal was to investigate the mechanism whereby ROS and FFA augment TRB3 expression. We demonstrate that in differentiated podocytes, ROS and palmitate enhance CHOP mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 5, A, B, C). Tunicamycin was used as a control, as it is a potent inducer of ER stress and CHOP expression (62). GRP78/BiP is a representative marker of ER stress and we show in Fig. 5D that palmitate increases GRP78 expression. It is notable that H2O2, which is associated in our study with augmented CHOP and TRB3 expression, is not associated with increased GRP78 expression.

Fig. 5.

ROS and FFA induce C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) expression and augment recruitment of CHOP and C/EBPβ to the proximal TRB3 promoter. Fully differentiated podocytes were treated for 4 h with H2O2 (A) and 24 h with palmitate (Palm) or BSA control (B). CHOP expression was assessed by real-time PCR. *P < 0.05 vs. control (1-way ANOVA). C: as above, podocytes were treated for 24 h with Palm, BSA, H2O2, and tunicamycin. Western blotting was performed and CHOP protein expression was assessed. This blot is representative of studies performed at least 3 times. D: Western blotting for GRP78/BiP expression was also performed. E: differentiated podocytes were treated for 4 h with 50 μM H2O2 or control and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies were performed. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with antibodies directed to CHOP, C/EBPβ, and the control IgG. E: represents real-time PCR amplification. *P < 0.05 vs. control, 1-way ANOVA. F: represents the 5′ region of the murine TRB3 promoter with the potential CHOP/C/EBPβ binding site at −61. Arrows represent the site of primers used for the ChIP studies. G: represents semiquantitiative PCR ChIP results (34 cycles). H: fully differentiated podocytes were transfected with pcDNA3-CHOP or control vector and 24 h later, TRB3 expression was assessed by Western blotting.

We previously showed in lymphocytes that PPAR-α ligands increase TRB3 expression by augmenting the binding of CHOP and C/EBPβ to the TRB3 promoter. Additionally, transcriptional studies demonstrated that mutation of the proximal CHOP/C/EBPβ binding site in the TRB3 promoter abolished transcriptional activation of the TRB3 promoter (48). Real-time PCR (Fig. 5E) and semiquantitative PCR studies (Fig. 5G) confirm that H2O2 enhances recruitment of CHOP and C/EBPβ to the proximal TRB3 promoter. Moreover, transfection of CHOP into fully differentiated podocytes augments TRB3 expression (Fig. 5H).

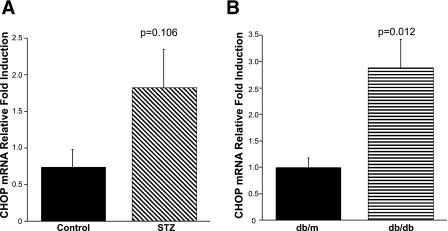

CHOP expression is also induced in murine diabetic kidneys.

Recent reports suggest that CHOP expression is enhanced in STZ-treated rodent kidneys (27, 60), and our studies support these findings. In STZ-treated mice, there was a trend for a greater than twofold increase in renal CHOP expression (Fig. 6A). In a similar manner, there was an almost threefold induction of CHOP expression in the kidneys of the db/db mice compared with the kidneys from the db/m controls (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

CHOP increases in diabetic mouse kidneys. Kidneys from STZ-treated (A) and db/db mice (B) and controls were harvested and mRNA expression of CHOP was evaluated by real-time PCR. There was a significant increase in CHOP expression in the db/db mice compared with the db/m controls and a trend for an increase in the STZ-treated mice (n = 5 mice per group, Student's t-test).

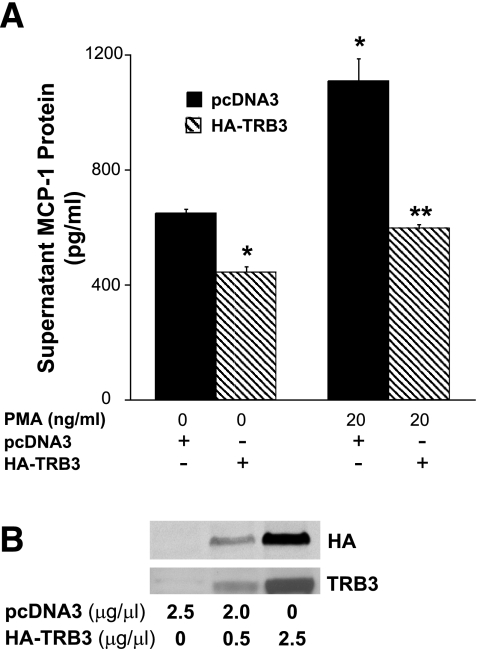

TRB3 inhibits MCP-1 expression in podocytes.

To further investigate the role that TRB3 may play in the diabetic kidney, podocytes were transfected with either a TRB3 expression plasmid or with an empty plasmid control (pcDNA3). Expression of TRB3 was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 7B). Cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA/TPA). Twenty-four hours after stimulation, we assessed MCP-1 protein expression by ELISA. PMA significantly augmented expression of MCP-1 in podocytes (Fig. 7A) and overexpression of TRB3 inhibited basal and stimulated protein expression of MCP-1.

Fig. 7.

A: TRB3 inhibits MCP-1 expression in podocytes. Fully differentiated podocytes were transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-HA-TRB3 (750 ng/well, 96-well plate), stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and supernatatant MCP-1 expression was assessed 24 h after transfection. Results are the average of studies performed at least 3 times. *P < 0.05 vs. pcDNA3-transfected, -unstimulated cells. **P < 0.05 vs. pcDNA3-transfected, PMA-stimulated cells. B: fully differentiated podocytes were transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-HA-TRB3, and 24 h later HA and TRB3 expression were assessed by Western blotting. TRB3 is efficiently transfected into differentiated podocytes.

DISCUSSION

In the current studies, we demonstrate for the first time that TRB3 expression is enhanced in kidneys derived from diabetic mice and further show that it is expressed in the glomeruli and in podocytes. Interestingly, hyperglycemia does not induce TRB3 expression. Instead, ROS and FFA augment podocyte TRB3 expression. CHOP, a marker of ER stress, is induced by ROS and FFA in conditionally immortalized podocytes and CHOP increases TRB3 expression. Moreover, H2O2 enhances binding of CHOP to the TRB3 promoter, suggesting that CHOP is involved in the transcriptional regulation of TRB3 expression. We further demonstrate that TRB3 reduces podocyte expression of MCP-1, suggesting that TRB3 may play a protective role in diabetic nephropathy.

TRB3 expression is augmented by multiple cellular stressors including thapsigargin, ER stress, fasting, arsenite, nutrient deprivation, nerve growth factor depletion, hypoxia, activation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and ethanol (5, 10, 16a, 29, 32, 34, 35, 46, 61). Upregulation of TRB3 expression has previously been described in livers (10) and hearts (56) of diabetic mice and we extend these findings to diabetic kidneys. In our studies, high glucose did not augment TRB3 expression. This is not surprising, as TRB3 expression increases in mouse livers under fasting conditions (10). The diabetic milieu is associated with oxidative stress (11) and in our studies ROS potently augmented TRB3 expression. Additionally, Tang and colleagues (56) showed that advanced glycation endproducts induce TRB3 expression and this is associated with overexpression of type 1 collagen in rat cardiac fibroblasts.

Our group and others showed that PPAR-α ligands upregulate TRB3 expression in lymphocytes and hepatocytes (23, 48). PPAR-α ligands are used clinically to reduce hypertriglyceridemia and lower the risks of cardiovascular disease (9). Montminy's group (40) elegantly demonstrated that TRB3 stimulates liver lipolysis by promoting the degradation of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid synthesis. We show for the first time that FFA induce TRB3 expression. This observation is currently limited to podocytes; however, we propose that TRB3 could function in a negative feedback loop that is designed to regulate the turnover of FFA. High levels of FFA could induce TRB3 expression, thereby reducing the activity of ACC and ultimately promoting the oxidation of FFA. These findings are likely to be of physiological relevance in other cell types and current studies are underway to test these hypotheses.

Little work has been published focusing on the effects of FFA on podocyte function. Using similar physiologic concentrations of palmitate, Saleem and Welsh's group (25) recently demonstrated that palmitate blocks insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in human podocytes. Palmitate treatment was also associated with reduced phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 and AKT (25). It is possible that in these studies, TRB3 is augmented by palmitate and this in turn inhibits phosphorylation of AKT.

Tribbles, the Drosophila homolog of TRB3, inhibits mitosis and causes G2 cell cycle arrest (15, 28, 47). Our previous work in lymphocytes showed that TRB3 induces G2 cell cycle arrest (48), and this is likely related to its ability to reduce transcription of the cyclin B1 promoter (31). Recent work in brain tumor cells suggests that TRB3 inhibits AKT and that this in turn activates autophagy and caspase-mediated apoptotic pathways (43). TRB3 also mediates human monocyte-derived macrophage apoptosis (49), and knockdown of TRB3 reduces ER stress-induced apoptosis (32). Diabetic kidney disease is associated with podocyte loss and defective podocyte function (26). However, in podocytes overexpressing TRB3, we have not yet observed increased apoptosis. In fact, TRB3 does not universally cause cell death. TRB3 was induced fivefold by erythropoietin and was associated with erythroblast survival (45). In postmitotic neuronally differentiated PC12 cells, coexpression of TRB3 with ATF4 prevented ATF4-induced apoptosis (33). Thus, TRB3's effects on survival or apoptosis are likely cell type and context dependent, and studies are underway to evaluate their survival effect on podocytes.

CHOP (C/EBPζ DDIT, GADD153) (39) is a transcription factor induced by and used as a marker of ER stress (36). CHOP can function as a transcriptional activator or suppressor (59) and in vivo C/EBPβ and CHOP form dimers during cellular stress (13). In lymphocytes and podocytes, we showed that CHOP and C/EBPβ bind to and activate the murine TRB3 promoter (48). Additionally, in this study, we demonstrate that transfection of CHOP into podocytes enhances TRB3 expression. Pavenstadt's group (4) first demonstrated that in podocytes, ROS induce CHOP expression. In their study, ROS did not increase podocyte proliferation, cell death, or growth arrest. Podocytes that retrovirally overexpressed CHOP had reduced expression of β1 and α3-integrin; unexpectedly, CHOP overexpression was associated with enhanced cell adhesion to collagen IV-coated plates (4). Although CHOP is considered to induce apoptosis in certain cell types, its function in podocytes remains incompletely understood.

Kidney injury in diabetic nephropathy is associated with the recruitment and activation of monocytes and macrophages in the kidney (14, 58). MCP-1 attracts and activates monocytes and macrophages and MCP-1 levels correlate with kidney injury in humans and diabetic mouse models (58). Mice deficient in MCP-1 have less manifestations of diabetic kidney disease (7, 57) and in general reduced MCP-1 levels attenuate expression of inflammatory renal diseases (21, 58). Evidence suggests that podocytes are an important source of MCP-1 (6, 7, 16) and our studies support these observations. Podocytes in culture express CCR2 (the MCP-1 receptor) (6) and podocyte CCR2 expression is greatly increased in patients with diabetic nephropathy (57). Recombinant human MCP-1 induces podocyte proliferation, migration (6), and reduces nephrin expression (57).

In our studies, TRB3 inhibits expression of MCP-1. Previously, we showed that TRB3 functions as a transcriptional inhibitor of cyclin B1 (31). TRB3 also inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (61), AP-1 (22), ATF-4 (33, 34), and PPAR-γ (53). The MCP-1 promoter has NF-κB, AP-1, and PPAR-γ response elements, and it is likely that TRB3 inhibits expression of MCP-1 at the transcriptional level. Several studies supported the concept that TRB3 may function as a scaffold protein to inhibit MAPK signaling cascades (19, 22, 56). MAPKs phosphorylate and activate transcription factors including NF-κB and AP-1 (20, 52). Furthermore, we postulate that TRB3 could inhibit the expression of other mediators of diabetic kidney injury driven by NF-κB (61) and AP-1, including TGF-β and plasminogen activator-1 (Fig. 8) (44).

Fig. 8.

Proposed therapeutic potential of TRB3 in diabetic kidney disease. Hyperglycemia and elevated FFA associated with diabetes augment ROS, which induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and activation of MAPK pathways. We propose that enhanced TRB3 expression could inhibit MAPK signaling thereby reducing NF-κB and AP-1 activation of inflammatory genes such as MCP-1, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and plasminogen activator-1 (PAI)-1.

Because MCP-1 plays a central role in inflammation associated with diabetic kidney disease, it is possible that further augmentation of TRB3 expression during the course of diabetes could be a therapeutic target in diabetes and other chronic inflammatory renal diseases.

GRANTS

These studies were performed with the support of the Department of Veterans Affairs Career Development Transition Award for R. Cunard; The National Institutes of Health Grant R01-DK-56248 to V. Vallon, Grant U01-DK-076133-02 to K. Sharma; and UCSD/UCLA Diabetes Endocrine Research Center Pilot and Feasibility Grant P30-DK-063491 and the University of California, San Diego Senate Grant awarded to R. Cunard.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. C. Glass's laboratory for providing HA-pcDNA3, Dr. M. Montminy's lab for the TRB3 antibody, and Dr. D. Ron's lab for mCHOP10.pcDNA1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer DC, Frkanec JT, Cromwell J, Clopton P, Cunard R. WY14,643, a PPARalpha ligand, attenuates expression of anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Clin Exp Immunol 150: 386–396, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton-Chess J, Giral M, Mengel M, Renaudin K, Foucher Y, Gwinner W, Braud C, Dugast E, Quillard T, Thebault P, Chiffoleau E, Braudeau C, Charreau B, Soulillou JP, Brouard S. Tribbles-1 as a novel biomarker of chronic antibody-mediated rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1116–1127, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bariety J, Nochy D, Mandet C, Jacquot C, Glotz D, Meyrier A. Podocytes undergo phenotypic changes and express macrophagic-associated markers in idiopathic collapsing glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 53: 918–925, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bek MF, Bayer M, Muller B, Greiber S, Lang D, Schwab A, August C, Springer E, Rohrbach R, Huber TB, Benzing T, Pavenstadt H. Expression and function of C/EBP homology protein (GADD153) in podocytes. Am J Pathol 168: 20–32, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowers AJ, Scully S, Boylan JF. SKIP3, a novel Drosophila tribbles ortholog, is overexpressed in human tumors and is regulated by hypoxia. Oncogene 22: 2823–2835, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt D, Salvidio G, Tarabra E, Barutta F, Pinach S, Dentelli P, Camussi G, Perin PC, Gruden G. The monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/cognate CC chemokine receptor 2 system affects cell motility in cultured human podocytes. Am J Pathol 171: 1789–1799, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Ozols E, Atkins RC, Rollin BJ, Tesch GH. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promotes the development of diabetic renal injury in streptozotocin-treated mice. Kidney Int 69: 73–80, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coers W, Brouwer E, Vos JT, Chand A, Huitema S, Heeringa P, Kallenberg CG, Weening JJ. Podocyte expression of MHC class I and II and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in experimental pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Clin Exp Immunol 98: 279–286, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunard R. The potential use of PPARalpha agonists as immunosuppressive agents. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 6: 467–472, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du K, Herzig S, Kulkarni RN, Montminy M. TRB3: a tribbles homolog that inhibits Akt/PKB activation by insulin in liver. Science 300: 1574–1577, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev 23: 599–622, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans JL, Maddux BA, Goldfine ID. The molecular basis for oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1040–1052, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawcett TW, Eastman HB, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Physical and functional association between GADD153 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta during cellular stress. J Biol Chem 271: 14285–14289, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galkina E, Ley K. Leukocyte recruitment and vascular injury in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 368–377, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grosshans J, Wieschaus E. A genetic link between morphogenesis and cell division during formation of the ventral furrow in Drosophila. Cell 101: 523–531, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu L, Hagiwara S, Fan Q, Tanimoto M, Kobata M, Yamashita M, Nishitani T, Gohda T, Ni Z, Qian J, Horikoshi S, Tomino Y. Role of receptor for advanced glycation end-products and signalling events in advanced glycation end-product-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in differentiated mouse podocytes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 299–313, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.He L, Simmen FA, Mehendale HM, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Chronic ethanol intake impairs insulin signaling in rats by disrupting Akt association with the cell membrane. Role of TRB3 in inhibition of Akt/protein kinase B activation. J Biol Chem 281: 11126–11134, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang ES, Basu A, O'Grady M, Capretta JC. Projecting the future diabetes population size and related costs for the US. Diabetes Care 32: 2225–2229, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey RK, Newcomb CJ, Yu SM, Hao E, Yu D, Krajewski S, Du K, Jhala US. Mixed-lineage kinase-3 stabilizes and functionally cooperates with tribbles 3 to compromise mitochondrial integrity in cytokine-induced death of pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 285: 22426–22436, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo JH, Jetten AM. NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional activation in lung carcinoma cells by farnesol involves p65/RelA(Ser276) phosphorylation via the MEK-MSK1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 283: 16391–16399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley VR, Rovin BH. Chemokines: therapeutic targets for autoimmune and inflammatory renal disease. Springer Semin Immunopathol 24: 411–421, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiss-Toth E, Bagstaff SM, Sung HY, Jozsa V, Dempsey C, Caunt JC, Oxley KM, Wyllie DH, Polgar T, Harte M, O'Neill LA, Qwarnstrom EE, Dower SK. Human tribbles, a protein family controlling mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. J Biol Chem 279: 42703–42708, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo SH, Satoh H, Herzig S, Lee CH, Hedrick S, Kulkarni R, Evans RM, Olefsky J, Montminy M. PGC-1 promotes insulin resistance in liver through PPAR-alpha-dependent induction of TRB-3. Nat Med 10: 530–534, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee HB, Yu MR, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Ha H. Reactive oxygen species-regulated signaling pathways in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: S241–S245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lennon R, Pons D, Sabin MA, Wei C, Shield JP, Coward RJ, Tavare JM, Mathieson PW, Saleem MA, Welsh GI. Saturated fatty acids induce insulin resistance in human podocytes: implications for diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3288–3296, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JJ, Kwak SJ, Jung DS, Kim JJ, Yoo TH, Ryu DR, Han SH, Choi HY, Lee JE, Moon SJ, Kim DK, Han DS, Kang SW. Podocyte biology in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl 106: S36–S42, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu G, Sun Y, Li Z, Song T, Wang H, Zhang Y, Ge Z. Apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress involved in diabetic kidney disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370: 651–656, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rorth P. Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell 101: 511–522, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayumi-Matsuda K, Kojima S, Suzuki H, Sakata T. Identification of a novel kinase-like gene induced during neuronal cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 258: 260–264, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGarry JD. Banting lecture 2001: dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 51: 7–18, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morse E, Selim E, Cunard R. PPARalpha ligands cause lymphocyte depletion and cell cycle block and this is associated with augmented TRB3 and reduced cyclin B1 expression. Mol Immunol 46: 3454–3461, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J 24: 1243–1255, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ord D, Meerits K, Ord T. TRB3 protects cells against the growth inhibitory and cytotoxic effect of ATF4. Exp Cell Res 313: 3556–3567, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ord D, Ord T. Characterization of human NIPK (TRB3, SKIP3) gene activation in stressful conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 330: 210–218, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ord D, Ord T. Mouse NIPK interacts with ATF4 and affects its transcriptional activity. Exp Cell Res 286: 308–320, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ 11: 381–389, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavenstadt H, Kriz W, Kretzler M. Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev 83: 253–307, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poli V. The role of C/EBP isoforms in the control of inflammatory and native immunity functions. J Biol Chem 273: 29279–29282, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qi L, Heredia JE, Altarejos JY, Screaton R, Goebel N, Niessen S, Macleod IX, Liew CW, Kulkarni RN, Bain J, Newgard C, Nelson M, Evans RM, Yates J, Montminy M. TRB3 links the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 to lipid metabolism. Science 312: 1763–1766, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiser J, von Gersdorff G, Loos M, Oh J, Asanuma K, Giardino L, Rastaldi MP, Calvaresi N, Watanabe H, Schwarz K, Faul C, Kretzler M, Davidson A, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, Sharpe AH, Kreidberg JA, Mundel P. Induction of B7-1 in podocytes is associated with nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest 113: 1390–1397, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosen P, Nawroth PP, King G, Moller W, Tritschler HJ, Packer L. The role of oxidative stress in the onset and progression of diabetes and its complications: a summary of a Congress Series sponsored by UNESCO-MCBN, the American Diabetes Association and the German Diabetes Society. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 17: 189–212, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Lorente M, Egia A, Vazquez P, Blazquez C, Torres S, Garcia S, Nowak J, Fimia GM, Piacentini M, Cecconi F, Pandolfi PP, Gonzalez-Feria L, Iovanna JL, Guzman M, Boya P, Velasco G. Cannabinoid action induces autophagymediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells. J Clin Invest 119: 1359–1372, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez AP, Sharma K. Transcription factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Expert Rev Mol Med 11: e13, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sathyanarayana P, Dev A, Fang J, Houde E, Bogacheva O, Bogachev O, Menon M, Browne S, Pradeep A, Emerson C, Wojchowski DM. EPO receptor circuits for primary erythroblast survival. Blood 111: 5390–5399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarzer R, Dames S, Tondera D, Klippel A, Kaufmann J. TRB3 is a PI 3-kinase dependent indicator for nutrient starvation. Cell Signal 18: 899–909, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seher TC, Leptin M. Tribbles, a cell-cycle brake that coordinates proliferation and morphogenesis during Drosophila gastrulation. Curr Biol 10: 623–629, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selim E, Frkanec JT, Cunard R. Fibrates upregulate TRB3 in lymphocytes independent of PPAR alpha by augmenting CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBP beta) expression. Mol Immunol 44: 1218–1229, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shang YY, Wang ZH, Zhang LP, Zhong M, Zhang Y, Deng JT, Zhang W. TRB3, upregulated by ox-LDL, mediates human monocyte-derived macrophage apoptosis. FEBS J 276: 2752–2761, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shankland SJ. The podocyte's response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 69: 2131–2147, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shankland SJ, Pippin JW, Reiser J, Mundel P. Podocytes in culture: past, present, and future. Kidney Int 72: 26–36, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sweeney SE, Firestein GS. Mitogen activated protein kinase inhibitors: where are we now and where are we going? Ann Rheum Dis 65, Suppl 3: iii83–iii88, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi Y, Ohoka N, Hayashi H, Sato R. TRB3 suppresses adipocyte differentiation by negatively regulating PPARgamma transcriptional activity. J Lipid Res 49: 880–892, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takasato M, Kobayashi C, Okabayashi K, Kiyonari H, Oshima N, Asashima M, Nishinakamura R. Trb2, a mouse homolog of tribbles, is dispensable for kidney and mouse development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 373: 648–652, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takasato M, Osafune K, Matsumoto Y, Kataoka Y, Yoshida N, Meguro H, Aburatani H, Asashima M, Nishinakamura R. Identification of kidney mesenchymal genes by a combination of microarray analysis and Sall1-GFP knockin mice. Mech Dev 121: 547–557, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang M, Zhong M, Shang Y, Lin H, Deng J, Jiang H, Lu H, Zhang Y, Zhang W. Differential regulation of collagen types I and III expression in cardiac fibroblasts by AGEs through TRB3/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2924–2932, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarabra E, Giunti S, Barutta F, Salvidio G, Burt D, Deferrari G, Gambino R, Vergola D, Pinach S, Perin PC, Camussi G, Gruden G. Effect of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine receptor 2 system on nephrin expression in streptozotocin-treated mice and human cultured podocytes. Diabetes 58: 2109–2118, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tesch GH. MCP-1/CCL2: a new diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for progressive renal injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F697–F701, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ubeda M, Vallejo M, Habener JF. CHOP enhancement of gene transcription by interactions with Jun/Fos AP-1 complex proteins. Mol Cell Biol 19: 7589–7599, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu J, Zhang R, Torreggiani M, Ting A, Xiong H, Striker GE, Vlassara H, Zheng F. Induction of diabetes in aged C57B6 mice results in severe nephropathy: an association with oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and inflammation. Am J Pathol 176: 2163–2176, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu M, Xu LG, Zhai Z, Shu HB. SINK is a p65-interacting negative regulator of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem 278: 27072–27079, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, Stevens JL, Ron D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev 12: 982–995, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]