Abstract

Macula densa (MD) cells in the cortical thick ascending limb (cTAL) detect variations in tubular fluid composition and transmit signals to the afferent arteriole (AA) that control glomerular filtration rate [tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF)]. Increases in tubular salt at the MD that normally parallel elevations in tubular fluid flow rate are well accepted as the trigger of TGF. The present study aimed to test whether MD cells can detect variations in tubular fluid flow rate per se. Calcium imaging of the in vitro microperfused isolated JGA-glomerulus complex dissected from mice was performed using fluo-4 and fluorescence microscopy. Increasing cTAL flow from 2 to 20 nl/min (80 mM [NaCl]) rapidly produced significant elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in AA smooth muscle cells [evidenced by changes in fluo-4 intensity (F); F/F0 = 1.45 ± 0.11] and AA vasoconstriction. Complete removal of the cTAL around the MD plaque and application of laminar flow through a perfusion pipette directly to the MD apical surface essentially produced the same results even when low (10 mM) or zero NaCl solutions were used. Acetylated α-tubulin immunohistochemistry identified the presence of primary cilia in mouse MD cells. Under no flow conditions, bending MD cilia directly with a micropipette rapidly caused significant [Ca2+]i elevations in AA smooth muscle cells (fluo-4 F/F0: 1.60 ± 0.12) and vasoconstriction. P2 receptor blockade with suramin significantly reduced the flow-induced TGF, whereas scavenging superoxide with tempol did not. In conclusion, MD cells are equipped with a tubular flow-sensing mechanism that may contribute to MD cell function and TGF.

Keywords: tubuloglomerular feedback, primary cilium, mechanosensor, juxtaglomerular apparatus

macula densa (MD) cells in the cortical thick ascending limb (cTAL) are the sensory element of the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA) and play an important role in the control of renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, and renin release. MD cells are strategically positioned in the JGA such that their apical membrane is exposed to the tubular fluid, whereas their basilar aspects are in contact with the effector cells of the JGA, namely the renin-producing juxtaglomerular granular cells and the contractile cells in the extraglomerular mesangium and the afferent arteriole (AA). Consistent with this anatomic localization, MD cells can detect alterations in tubular fluid characteristics (for example, ionic composition) and generate and release chemical mediators that act on JGA effectors in a paracrine fashion. According to the prevailing paradigm, elevations in tubular NaCl concentration ([NaCl]) at the MD trigger basolateral ATP release from these cells, which directly or through its breakdown to adenosine cause AA vasoconstriction and reductions in glomerular filtration rate [tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF)] (6, 7, 14, 22, 35, 39, 40).

Identification of the luminal characteristic(s) that is sensed by the MD was the topic of intense research more than 25 years ago conducted by several laboratories, and the results were long debated (1, 2, 4, 22, 35). In particular, variables such as tubular fluid [NaCl], flow rate, and osmolality were considered as top candidates for the characteristic that can trigger TGF (1, 2, 4, 22, 35). Briggs et al. (4) and Schnermann and Briggs (35) found that most experimental maneuvers that cause TGF ultimately translate into alterations in tubular fluid [NaCl] at the MD, which has prevailed as the key luminal signal for TGF. However, increases in the distal microperfusion rate of a variety of electrolyte (including chloride-free) and nonelectrolyte solutions were demonstrated to elicit TGF responses (1, 21), suggesting the role of increased fluid flow per se. These earlier reports also suggest that there may be more than one tubular signal that MD cells can detect. Support for this view includes, for example, the recent study by our laboratory on the localization of the succinate receptor GPR91 at the apical membrane of MD cells that can sense alterations in local tissue metabolism (41).

In past years, changes in tubular fluid flow rate and the flow-sensing primary cilia and their associations with ATP release received much attention (10, 20, 28–31). Primary cilia are solitary, immotile organelles that sense extracellular chemical and mechanical signals and transduce them into cellular responses. Primary cilia are well-established fluid flow sensors in many organs and cell types, including renal epithelia (10, 20, 28–31). Bending of cilia in most cell types can trigger elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) via the function of ciliary membrane ion channels and associated proteins, including polycystins (30). Interestingly, earlier electron microscopy work by several laboratories demonstrated the presence of primary cilia in MD cells (11, 12, 38, 43), suggesting direct flow sensing by these cells. Flow-induced ATP release from MD cells is intriguing since ATP release is integral in TGF (3, 6, 14, 27). A recent study from our laboratory found that elevations in tubular fluid flow rate trigger an ATP-dependent calcium wave that propagates in the JGA and beyond (27). Also, a number of special MD and JGA dissection techniques (3, 14, 25–27) and their experimental applications that allow the precise manipulation of the MD environment have been developed recently. Therefore, we revisited the long-debated issue of direct fluid flow sensing by MD cells using these freshly dissected special JGA preparations in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL6J mice (6–8 wk of age) were used from our colony bred at the University of Southern California. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California. For anesthesia, the combination of ketamine and inactin (10 mg/100 g body wt each) was used.

In vitro isolated and microperfused glomerulus: JGA.

Individual glomeruli with AA and attached cTAL-MD segment were dissected freehand from freshly harvested kidneys of anesthetized mice and perfused in vitro using methods that were described before (24–27). Briefly, the AA was cannulated and microperfused, and the AA vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) were loaded with fluo-4 AM added to the bathing solution (1 μM, 25°C, for 15 min) for intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) imaging. In some experiments, the ratiometric calcium fluorophore fura-2 was added to the bath and used as described before (25) for imaging AA VSMC [Ca2+]i. The most often used dissection technique was the open MD preparation, in which the cTAL tubule segments surrounding the MD were completely removed so the apical surface of MD cells was directly accessible from the bath for the use of stimulating or perfusion pipettes (Fig. 1). In some preparations, the MD plaque was also removed for the purpose of control experiments. Viability of each preparation was confirmed by the existence of small, spontaneous, and temporary vasoconstrictions in the AA. Dissection media were prepared from DMEM mixture F-12 (Sigma-Aldrich). Fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) was added at a final concentration of 3%. Arteriole perfusion and bath fluid was a modified Krebs-Ringer-HCO3 buffer containing (in mM) 110 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 0.96 NaH2PO4, 0.24 Na2HPO4, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 5.5 d-glucose, and 100 μM l-arginine. In some preparations, the cTAL-MD tubular segment was perfused with an isosmotic, varying, NaCl-containing modified Ringer's solution consisting (in mM) of 10 NaCl, 135 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) cyclamate, 5 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.6 Na2HPO4, 0.4 NaH2PO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 5 d-glucose, and 10 HEPES. The NaCl content of tubular perfusate was varied by changing the NaCl/NMDG cyclamate ratio, as described before (24, 26). The pH of the solutions was adjusted to 7.4. Each preparation was transferred to a thermoregulated Lucite chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M, ×40 oil immersion objective). The preparation was kept in the dissection solution, and also, temperature was kept at 4°C until cannulation of the arteriole and tubule was completed and then gradually raised to 37°C for the remainder of the experiment. The bath was continuously exchanged (1 ml/min) and oxygenized (95% O2-5% CO2) throughout the whole experiment. The preparation was stimulated by one of the following stimuli. 1) Lateral fluid flow was applied directly to and parallel with the MD apical surface using a perfusion pipette (Fig. 1) and different [NaCl] solutions (0, 10, 80, and 135 mM). Figure 1, A and B, shows the specific experimental setup and positioning of the preparation. The perfusion pipette was placed pointing toward the MD but away from the AA, and the constant bath superfusion flowing parallel with the perfusion pipette washed the perfusate away from the AA. This arrangement helped to minimize the direct mechanical or chemical (varying [NaCl]) effect of the perfusate on the AA. When NaCl was completely removed from the solution, NaCl was isosmotically substituted with NMDG cyclamate, KCl with potassium gluconate, and CaCl2 with calcium gluconate. In other studies, tempol (100 μM) or suramin (50 μM, 10 min bath preincubation each) was added to eliminate the flow-induced generation of reactive oxygen species or block P2 purinergic receptors, respectively. If not indicated otherwise, the stimulus was applied by increasing fluid flow from the perfusion pipette from 2 to 20 nl/min. Calibration of fluid perfusion rates was performed as described before (27). 2) Several MD cilia were bent directly and simultaneously with a glass micropipette under no-flow conditions. The primary cilia of MD cells were bent by moving a large micropipette (10 μm in diameter) with the help of a micromanipulator (MP-225; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) parallel with and close to the apical membrane of MD cells. This precise maneuver was performed under direct visual control by using 50–50% light split between the microscope eyepiece and detectors, differential interference contrast optics, and under high optical magnification (up to ×160) using a ×100 oil immersion objective combined with a ×1.6 microscope lens to make sure that the pipette did not touch the cell surface. In some preparations, a more robust mechanical stimulation of the MD cell's apical surface was performed by directly poking several MD cells in the same preparation with the tip of a perfusion pipette (2–3 μm in diameter). 3) The intact cTAL-MD tubular segment was perfused with different [NaCl] solutions (10 or 80 mM). In all preparations, elevations in [Ca2+]i of AA VSMCs were monitored by increases in VSMC fluo-4 fluorescence intensity (F) or fura-2 340/380 nm ratio (R) normalized to baseline (F/F0 or R/R0, respectively). Fluo-4 or fura-2 fluorescence emission was detected every 2 s at 530 ± 20 nm in response to excitation at 490 ± 20 nm (for fluo-4) or 340/380 nm (for fura-2) using a 75W Xenon light source-based fluorescence imaging system (Stallion; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging/Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Gottingen, Germany).

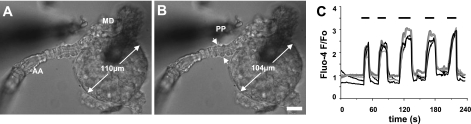

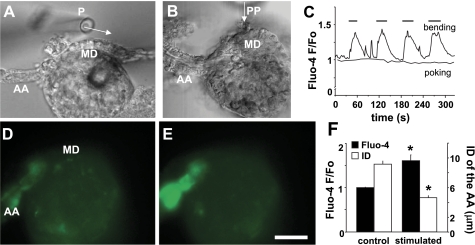

Fig. 1.

Direct stimulation of the macula densa (MD) by increased fluid flow. Differential interference contrast (DIC) image of an afferent arteriole (AA)-attached glomerulus and MD preparation in which the tubule segments surrounding the MD were completely removed. The apical surface of MD cells was directly accessible from the bath with a perfusion pipette (PP). Compared with 2 nl/min control perfusion (A), the application of 20 nl/min lateral fluid flow from the PP (0 mM NaCl solution) directly to the MD apical surface produced vasoconstriction of the AA (arrows) and elevations in vascular smooth muscle cell VSMC cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i; B). Note that in addition to the AA the whole glomerulus contracted as well. Scale is 20 μm. C: representative [Ca2+]i recordings from different VSMCs (indicated by different shades of gray) in the AA during flow-induced tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF). The flow stimulus (20 nl/min) was applied using 0 mM NaCl solution. When the same maneuver was repeated 5 times within 4 min, the response showed no signs of desensitization.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunofluorescence using mouse kidney sections was performed as described previously (24, 37, 41). Briefly, kidneys were fixed in situ by perfusion of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Coronal kidney sections were postfixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, 5-μm tissue sections were deparaffinized in toluene and rehydrated through graded ethanol. Sections were subjected to microwave antigen retrieval (10 min) and were blocked for 30 min with 20% goat serum in PBS to reduce nonspecific binding. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:100 dilution of monoclonal anti-acetylated α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by 1:500 Alexa 594-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h. Sections were mounted with Vectashield media containing 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole for nuclear staining (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and imaged using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal fluorescence imaging system (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany).

Data analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing VSMC fluo-4 F/F0, fura-2 R/R0, and AA internal diameter (ID) values before vs. after flow stimulation using a paired Student t-test. To compare observations from multiple groups, a one-way ANOVA was used, followed by post hoc tests (Bonferroni correction) for multiple comparisons. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Direct stimulation of MD cells with fluid flow.

To directly examine whether MD cells are able to sense changes in tubular fluid flow rate, a single glomerulus with attached AA and MD was dissected. The entire MD plaque was exposed by removing the surrounding cTAL tubule segments (open MD preparation; Fig. 1). The apical surface of MD cells was directly accessible to the bathing solution, and a variety of mechanical stimuli were applied by using glass micropipettes. First, a perfusion pipette was placed close to the edge of the MD plaque parallel with its apical surface. Changes in fluo-4 fluorescence intensities monitored over the cytoplasm of AA VSMCs and the internal diameter of the AA were measured (before vs. after the flow stimulus) as indices of TGF responses in all experiments. The application of lateral fluid flow from the perfusion pipette directly to the MD apical surface (from 2 to 20 nl/min using 0 mM [NaCl] perfusate) produced vasoconstriction of the AA and elevations in VSMC [Ca2+]i, as indicated by the increases in fluo-4 F/F0 ratio (Fig. 1). Repeated fluid flow stimulations in the same preparation every 45 s resulted in similar VSMC [Ca2+]i responses, which showed no signs of desensitization (Fig. 1C). [Ca2+]i elevations were also detected in other cell types of the JGA-glomerulus complex, including mesangial cells and podocytes, but not in MD cells. In MD cells, the fluo-4 F/F0 ratio was 0.99 ± 0.03 before and 1.03 ± 0.07 after the flow stimulus (P = 0.61, n = 7). In addition to AA vasoconstriction, the high fluid flow rate triggered the contraction of the entire glomerular tuft (glomerular diameter reduced from 114 ± 3 μm to 106 ± 2 μm, n = 9, P < 0.05).

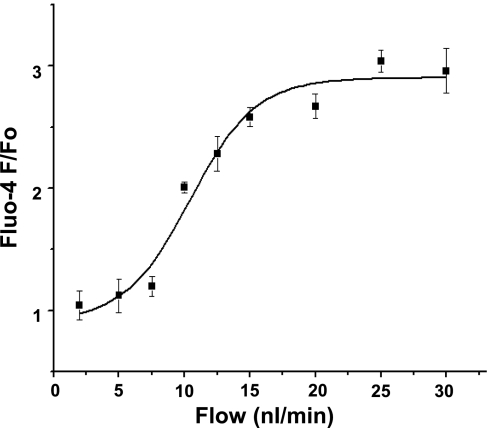

Importantly, the magnitude of elevations in AA VSMC fluo-4 fluorescence intensity was dependent on MD fluid flow rate. In other experiments where the open MD plaque approach was used, preparations were first perfused with the baseline rate of 2 nl/min, and then the flow was increased to 5–30 nl/min in several increments [to 5, 7.5, 10 (n = 5 each), 12.5 (n = 3), 15 (n = 4), 20, 25, and 30 nl/min (n = 5 each) from 6 different preparations]. Figure 2 demonstrates that a sigmoidal flow-response relationship was found between VSMC fluo-4 F/F0 and the fluid flow applied to the MD apical surface in the 0–30 nl/min range. The flow with the half-maximal effect was 10.4 nl/min.

Fig. 2.

The relationship between fluid flow rate at the MD and AA smooth muscle cell [Ca2+]i changes. Data points represent the average ± SE of 3–5 individual measurements at flow rates of 2, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 20, 25, and 30 nl/min from 6 different open MD plaque preparations. The stimulating flow rate with the half-maximal effect was 10.4 nl/min.

The flow-induced TGF is independent of [NaCl].

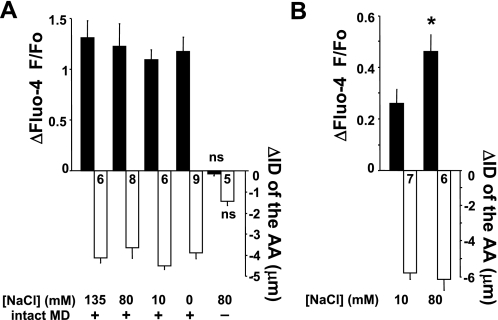

It is well established that elevations in tubular [NaCl] at the MD trigger TGF responses (35, 39). Therefore, we studied [NaCl] dependence of the above-described fluid flow-induced TGF. Perfusion solutions with [NaCl] of 135, 80, 10, and 0 mM were used in the constant 135 mM [NaCl] bath, and when fluid flow at the MD was increased from 2 to 20 nl/min they all elicited significant [Ca2+]i elevations in AA VSMCs (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 2.29 ± 0.13, 2.21 ± 0.10, 2.08 ± 0.21, and 2.15 ± 0.13, respectively) and AA vasoconstriction (ID decreased by 4.1 ± 0.3, 3.9 ± 0.4, 5.1 ± 0.3, and 4.1 ± 0.6 μm, respectively; n = 6–9, as shown in Fig. 3A). Perfusion solutions with lower [NaCl] appeared to produce smaller VSMC [Ca2+]i responses (Fig. 3A), but the differences between groups were not statistically significant. Importantly, the high-flow-induced TGF was completely abolished by the removal of the MD plaque. In these preparations the Fluo-4 F/F0 ratio in AA VSMCs decreased by 0.03 ± 0.02, and the AA ID decreased by 0.04 ± 0.4 μm when flow (using 80 mM [NaCl]) was increased from 2 to 20 nl/min (P = 0.94, n = 5) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Summary of the changes in AA smooth muscle cell [Ca2+]i and AA internal diameter (ID) during MD fluid flow-induced TGF using the open MD plaque preparation (A) or the intact cortical thick ascending limb (cTAL)-double perfusion model (B). Flow at the MD was increased from 2 to 20 nl/min. The tissue was bathed in 135 mM NaCl containing Ringer's solution in all preparations. Numbers are shown in each column. All changes are significant (P < 0.05) if not indicated (ns, nonsignificant). A: significant AA vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i responses were observed regardless of the applied fluid [NaCl]. Even the application of 0 mM [NaCl] perfusion solution induced TGF. B: using 10 mM [NaCl] solution, the application of increased fluid flow from 2 to 20 nl/min evoked significant [Ca2+]i elevations in the AA VSMCs and AA vasoconstriction. When 80 mM [NaCl] solution was used, significantly higher flow-induced [Ca2+]i elevations were observed compared with the effect with 10 mM [NaCl] (*P < 0.05).

Similar experiments were performed using the intact, microperfused cTAL-MD tubule preparation with simultaneously perfused AA. When the cTAL was perfused with 80 mM [NaCl] solution and the flow rate was increased from 2 to 20 nl/min, AA vasoconstriction and significant [Ca2+]i elevations in AA VSMCs were observed (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 1.45 ± 0.11, and AA ID was reduced by 6.2 ± 0.2 μm, P < 0.05, n = 6; Fig. 3B). When a cTAL perfusion solution with 10 mM [NaCl] was used, the same fluid flow increase resulted in still significant TGF responses (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 1.24 ± 0.07, and AA ID was reduced by 5.7 ± 0.3 μm; n = 7), but the VSMC [Ca2+]i response was smaller compared with that when 80 mM [NaCl] was used (Fig. 3B). Thus, it appears that significant flow-induced TGF responses were observed under a variety of [NaCl] conditions (0–135 mM); however, the effects of flow were more pronounced when perfusate [NaCl] increased simultaneously.

Additional experiments were performed using the well-established ratiometric calcium fluorophore fura-2 to control for the validity of fluo-4 measurements. In the intact cTAL-double perfusion model, the normalized fura-2 ratio (R/R0) in AA VSMCs increased to 1.24 ± 0.02 (P < 0.05, n = 4) in response to increased tubular flow from 2 to 20 nl/min using 10 mM [NaCl] and to 1.39 ± 0.02 (P < 0.05, n = 4) when 80 mM [NaCl] was used. In the open MD preparation, the flow stimulus caused an increase in fura-2 R/R0 in AA VSMCs to 1.67 ± 0.1 (P < 0.05, n = 5) using 10 mM [NaCl] and to 1.9 ± 0.05 (P < 0.05, n = 4) when 80 mM [NaCl] was used. Therefore, the AA VSMC [Ca2+]i responses detected by fura-2 were essentially the same as shown in Fig. 3, A and B, using fluo-4.

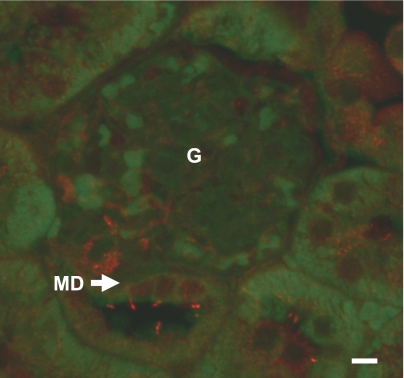

Identification of the flow sensor.

As in other cell types and nephron segments, the most plausible sensor of changes in tubular fluid flow rate at the MD is the primary cilium (10, 20, 28–31). Therefore, immunofluorescence studies were performed, using mouse kidney sections to localize α-tubulin, a ubiquitous component of primary cilia. Similar to other nephron segments, 5- to 8-μm-long cilia were found on the apical surface of the MD plaque. Each MD cell appeared to possess only one primary cilium (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence labeling of α-tubulin in the mouse kidney. Each MD cell has one 5- to 8-μm-long primary cilium (red) at the apical membrane. Autofluorescence (green) was used as a background to visualize tissue structure. Scale is 10 μm. G, glomerulus.

To examine whether MD primary cilia can act as fluid flow sensors, a different method of mechanical stimulation was performed, using the open MD plaque preparation. Rather than the application of fluid flow in the previous experiments, these studies were performed under no-flow conditions. A glass micropipette (10 μm in diameter) was held by a motorized micromanipulator and moved parallel with and close to the MD luminal membrane without the apical surface of the cells being touched (Figs. 5A). This stimulus resulted in the simultaneous bending of several MD cilia, confirmed visually using a ×100 oil immersion objective (Leica Microsystems). Direct, flow-independent MD cilia bending caused significant elevations in AA VSMC [Ca2+]i (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 1.60 ± 0.12) and AA vasoconstriction (AA ID decreased from 9.2 ± 0.4 to 4.7 ± 0.3 μm; n = 6) (Fig. 5, C–F). These elevations in VSMC [Ca2+]i were specific for cilia bending since other mechanical stimuli, for example, direct touching and poking of several MD cells in the same preparation with a perfusion micropipette (2–3 μm in diameter), did not produce changes in VSMC [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5, B and C). Again, MD cells themselves did not respond to cilium bending with [Ca2+]i elevations (Fig. 5, D and E). Similar to flow-induced TGF, repeating the bending stimulus in the same preparation several times produced equal VSMC [Ca2+]i responses, with no signs of desensitization (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Stimulation of the MD cells by directly bending their apical cilia with a glass micropipette under no-flow conditions. Representative DIC (A) and fluorescent [Ca2+]i images (fluo-4 labeling: green, D–E) before (A and D) and after (E) TGF was induced by moving a large micropipette (P; 10 μm in diameter) parallel with and close to the MD luminal membrane without touching the apical surface of the cells, as indicated by the arrow in A. B: direct, frontal poking of the MD cell's apical surface was performed using a small PP (2–3 μm in diameter). C: changes in fluo-4 intensity in VSMCs of the AA after repeated mechanical stimuli in the same preparation by cilia bending (as shown in A). In contrast, direct, repeated poking of MD cells with a perfusion pipette produced no changes in VSMC [Ca2+]i. F: summary of the cilia bending data. *P < 0.05, stimulated vs. control; n = 6. Scale is 20 μm.

Signaling mechanism of flow-induced TGF.

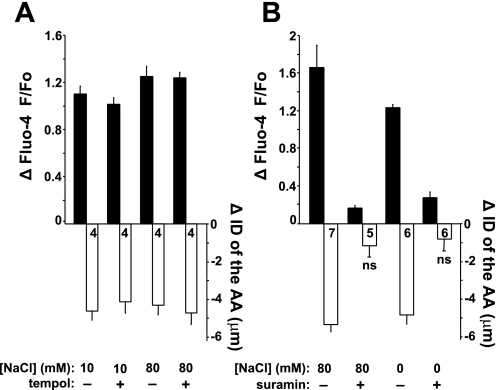

As described above, MD cells did not produce [Ca2+]i elevations in response to either flow stimulation or direct cilia bending. Therefore, we aimed to test the involvement of two well-characterized flow-dependent signaling systems. Recent studies suggested that elevations in tubular fluid flow rate can trigger the production of superoxide, and this mechanism was implicated in TGF (9, 18, 32, 44). To investigate whether superoxide was involved in the fluid flow-induced TGF described above, the superoxide scavenger tempol (100 μM) was used in the open MD plaque preparation. The addition of tempol failed to alter the magnitude of [Ca2+]i elevations in AA VSMCs in response to increasing MD fluid flow rate from 2 to 20 nl/min using either 10 mM [NaCl] (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 2.10 ± 0.06 or 2.01 ± 0.04 with or without tempol, respectively) or 80 mM [NaCl] perfusion solutions (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to 2.24 ± 0.04 or 2.25 ± 0.08 with or without tempol, respectively). Similarly, tempol had no effect on flow-induced AA vasoconstriction (AA ID reduced by 4.1 ± 0.6 or 4.6 ± 0.5 μm with or without tempol, respectively, using 10 mM [NaCl], and 4.7 ± 0.6 or 4.3 ± 0.5 μm with or without tempol, respectively, using 80 mM [NaCl], P < 0.05, n = 4 each; Fig. 6A). Also, the release of ATP from MD cells and its role in TGF are well established (3, 6, 14). Using the same open MD preparation, we studied whether extracellular ATP and purinergic calcium signaling were involved in fluid flow-induced TGF. In the presence of the nonselective P2 purinergic receptor blocker suramin (100 μM), the flow-induced elevations in AA VSMC [Ca2+]i were significantly blunted using either the 80 (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to only 1.15 ± 0.02 vs. 2.64 ± 0.46 without suramin; n = 5 and 7, respectively) or 0 mM [NaCl] perfusion solutions (fluo-4 F/F0 increased to only 1.26 ± 0.06 vs. 2.21 ± 0.06 without suramin; n = 6 each). Similarly, suramin administration caused significant inhibition of the flow-induced AA vasoconstriction (AA ID reduced by 0.8 ± 0.7 or 4.9 ± 1.2 μm with or without suramin, respectively, using 0 mM [NaCl], and 1.2 ± 0.8 or 5.4 ± 1.0 μm with or without suramin, respectively, using 80 mM [NaCl]; Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Signaling mechanism of flow-induced TGF. Summary of the changes in AA smooth muscle cell [Ca2+]i and AA ID during flow-induced TGF (increasing fluid flow rate from 2 to 20 nl/min) using the open MD plaque preparation. A: the addition of tempol (100 μM) to the bathing solution did not alter [Ca2+]i and vasoconstrictor responses using either the 10 or 80 mM [NaCl] solution, confirming that these results were independent of the flow-induced generation of reactive oxygen species. B: evidence for the involvement of purinergic signaling in flow-induced TGF. The bath application of suramin (50 μM) significantly decreased the flow-induced [Ca2+]i elevations in AA VSMCs and blocked AA vasoconstriction using either 0 or 80 mM [NaCl] perfusate. All changes are significant (P < 0.05) if not indicated. Numbers are shown in each column.

DISCUSSION

This study revisited the classic, long-debated topic of MD luminal sensing mechanisms and aimed to investigate whether increases in fluid flow rate per se can activate TGF responses. The application of fluid flow directly on the apical surface of freshly dissected MD cells or in intact microperfused cTALs triggered TGF responses (AA vasoconstriction, contraction of the entire glomerular tuft) regardless of the [NaCl] of the applied solution. There was a sigmoidal relationship between the magnitude of TGF responses and MD fluid flow in the 0–30 nl/min range, with the half-maximal effect at 10.4 nl/min. The effects of fluid flow were reproducible in the same preparation every 45 s without signs of desensitization. The present studies also tested whether MD cell primary cilia can act as flow sensors. Acetylated α-tubulin immunofluorescence studies confirmed that mouse MD cells possess apical primary cilia. Bending of MD cilia directly with a micropipette under no-flow conditions triggered TGF, whereas nonspecific mechanical stimulation (poking) of MD cells had no effect. Inhibition of the P2 purinergic receptors blocked the fluid flow-induced TGF responses, suggesting the involvement of ATP and purinergic signaling. Our data suggest that, in addition to detecting tubular salt, MD cells are equipped with a tubular fluid flow-sensing mechanism that may be another important MD cell sensory function and regulator of TGF.

Physiologically, elevations in loop of Henle fluid flow rate parallel increases in tubular salt content at the MD and trigger TGF-mediated vasoconstriction of the AA, which causes reduced glomerular filtration rate (35). Earlier in vivo micropuncture experiments used a variety of loop perfusion techniques (open or closed loop, anterograde or retrograde, different fluid compositions), but the most often used stimulus was the increase in the rate of perfusion from 0 to 40 nl/min (1, 2, 4, 22, 35). Several luminal variables such as tubular fluid [NaCl], flow rate, and osmolality were considered as the MD signal that triggers TGF (1, 2, 4, 22, 35). Briggs et al. (4) and Schnermann and Briggs (35) established the existing paradigm claiming that the alteration in tubular fluid [NaCl] at the MD is the key luminal signal for TGF. However, Bell et al. (1) and Navar and colleagues (21, 22) found that under some conditions TGF responses were dissociated from distal tubular chloride, suggesting that MD cells can detect other luminal signal(s) as well. Ever since then the importance of tubular fluid flow rate has been largely overlooked. Interestingly, a recent in vitro microperfusion study from our laboratory found that elevated tubular flow rate resulted in more pronounced TGF responses compared with those evoked by the application of high [NaCl] at the MD (27). These findings prompted us to study the flow response in more detail, using tissue preparations that allow direct assessment of the flow stimulus at the point of the MD.

The significantly stronger fluid flow-induced TGF responses observed when fluid flow rate and [NaCl] increased simultaneously (Fig. 3B) are consistent with the paradigm that MD cells can sense tubular salt via reabsorption through Na/K/2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) (4, 6, 14, 16, 34, 35). However, under the conditions of reduced NaCl gradient (including 0 mM NaCl solution to eliminate NKCC2-mediated MD NaCl uptake), the increased fluid flow rate was still able to trigger significant TGF responses (Fig. 3A). These findings strongly support the importance of increased fluid flow per se independent of [NaCl], although under physiological conditions, tubular salt content and flow rate increase simultaneously during TGF. Inhibition by furosemide is a hallmark of TGF responses in vivo (4, 35), and accordingly, in our previous work furosemide blocked flow-induced TGF responses (27). However, the significant flow-induced TGF responses observed in the present study with 0 mM NaCl solutions seem to be in conflict with the earlier furosemide data (4, 27, 35). The reason for this is not clear, but the different experimental approach and factors downstream of MD NKCC2 may provide an explanation. Furosemide acting on NKCC1 expressed in AA VSMCs causes vasodilatation (23), which in effect could have masked the tubular fluid flow component of TGF in vivo. In addition, chloride removal from the tubular fluid causes MD cell shrinkage, which can activate various signaling cascades, including MAP kinases and PGE2 generation (8, 45), but also significant alkalinization of the MD due to unopposed apical Na/H exchange activity (24). High MD pH has been linked to increased production of nitric oxide (NO), another vasodilator, and blunted TGF (17, 42). It is likely that PGE2 and NO generation is more intact in vivo compared with our in vitro model, and it can explain the complete TGF inhibition by chloride removal in that model (4, 35). Also, it should be noted that the high bath [NaCl] in the open MD preparation caused AA vasoconstriction under baseline conditions; however, after recovery and adaptation (33), the AA was still sensitive to MD fluid flow elevations. Even the lowering of MD salt (from 135 to 0 mM NaCl) in that preparation with increased fluid flow rate induced TGF, further suggesting the important role of fluid flow. Regarding the role of MD cell volume, it appears that different stimuli that trigger TGF can be associated with MD cells either swelling (26) or shrinking (15), suggesting the lack of the direct involvement of MD cell volume in TGF.

It is unlikely that AA VSMCs directly responded to fluid flow stimulations independent of the MD. The finding that the high-flow-induced TGF was fully dependent on the presence of an intact MD plaque (Fig. 3A) is strongly supportive of a specific, MD-mediated mechanism. Also, careful positioning of the preparation prevented any fluid flow toward the AA. As mentioned above, significant reductions in bath [NaCl] triggered vasoconstriction as well, although reductions in Cl− flux in VSMCs would be expected to produce vasodilatation, similar to the effects of furosemide (23).

The MD flow-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i in VSMCs of proximal AA segments and intraglomerular mesangial cells and podocytes are consistent with the recently described propagation of a calcium wave during TGF (27). Also, the involvement of purinergic signaling in MD flow-induced TGF (Fig. 6B) further supports the important role of MD ATP release in TGF (3) and the recently established mediator role of ATP in cilia-mediated fluid flow sensing (10). Figure 6B shows that the inhibition of P2 purinergic receptors did not completely abolish the flow-induced TGF response, suggesting the involvement of other mediators, for example, adenosine (6, 36, 40). Interestingly, the flow-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i of AA VSMCs were considerably higher when the open MD preparation (Fig. 3A) vs. the intact microperfused tubule technique was used (Fig. 3B). This is likely the result of stronger mechanical stimulation (cilia bending) caused by the higher fluid velocity in that model (same flow rate applied directly on the MD cell's surface via a small pipette vs. a large tubule with diameters of 2–3 μm or >10 μm, respectively). Nevertheless, the magnitude of AA vasoconstriction was similar in the two models (Fig. 3, A and B).

The primary cilium is a well-established fluid flow sensor in renal epithelia (10, 20, 28–31) in which cilia bending can trigger elevations in [Ca2+]i (28). The present data are consistent with earlier electron microscopy work by several laboratories (11, 12, 38, 43) and confirm the presence of primary cilia in mouse MD cells, suggesting that MD cells are equipped with a similar flow-sensing machinery. However, MD cells did not produce [Ca2+]i elevations in response to cilia bending (Fig. 5). The lack of a robust MD calcium response during TGF is also consistent with earlier reports (13, 25, 27). It is well established that mechanosensation via primary cilia is a cell- and tissue-specific mechanism that may involve calcium-independent signaling pathways (19). Our data suggest that the mechanisms responsible for cilium-mediated flow sensing in MD cells and in other renal epithelia are distinct. One potential underlying mechanism that was addressed in the present studies is oxidative stress. Tubular fluid flow elevations in the TAL have been shown to induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (9). Also, the role of superoxide in TGF is well established (5, 18, 32, 44). However, in our studies the scavenging of superoxide by tempol had no effect on the magnitude of flow-induced TGF response (Fig. 6A), suggesting that this process is not involved in MD tubular fluid flow sensing.

In conclusion, our data suggest that, in addition to detecting tubular salt, MD cells are equipped with a tubular fluid flow-sensing mechanism that may be another important MD cell sensory function directly involved in TGF. Since a number of genetic cilia-deficient mouse models are available, it should be possible to address the role of MD primary cilia in TGF in vivo in future work.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-064324 and American Heart Association (AHA) Established Investigator Award 0640056N to J. Peti-Peterdi. A. Sipos was supported by an AHA Western Affiliate Postdoctoral Research Fellowship during these studies.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell PD, McLean CB, Navar LG. Dissociation of tubuloglomerular feedback responses from distal tubular chloride concentration in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 240: F111–F119, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell PB, Navar LG. Relationship between tubulo-glomerulat feedback responses and perfusate hypotonicity. Kidney Int 22: 234–239, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell PD, Lapointe JY, Sabirov R, Hayashi S, Peti-Peterdi J, Manabe K, Kovacs G, Okada Y. Macula densa cell signaling involves ATP release through a maxi anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4322–4327, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs J, Schubert G, Schnermann J. Further evidence for an inverse relationship between macula densa NaCl concentration and filtration rate. Pflügers Arch 392: 372–378, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlström M, Persson AE. Important role of NAD(P)H oxidase 2 in the regulation of the tubuloglomerular feedback. Hypertension 53: 456–457, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castrop H. Mediators of tubuloglomerular feedback regulation of glomerular filtration: ATP and adenosine. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 189: 3–14, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyton AC, Langston JB, Navar G. Theory for renal autoregulation by feedback at the juxtaglomerular apparatus. Circ Res 15, Suppl: 187–197, 1964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanner F, Chambrey R, Bourgeois S, Meer E, Mucsi I, Rosivall L, Shull GE, Lorenz JN, Eladari D, Peti-Peterdi J. Increased renal renin content in mice lacking the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F937–F944, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Flow increases superoxide production by NADPH oxidase via activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport and mechanical stress in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F993–F998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hovater MB, Olteanu D, Hanson EL, Cheng NL, Siroky B, Fintha A, Komlosi P, Liu W, Satlin LM, Bell PD, Yoder BK, Schwiebert EM. Loss of apical monocilia on collecting duct principal cells impairs ATP secretion across the apical cell surface and ATP-dependent and flow-induced calcium signals. Purinergic Signal 4: 155–170, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaissling B, Kriz W. Morphology of the loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting duct. In: Handbook of Physiology. Renal Physiology, Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1992, sect. 8, vol. I, chapt. 3, p. 109–167 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaissling B, Dorup J. Functional anatomy of the kidney. In: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1995, vol. 117, p. 1–66 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komlosi P, Banizs B, Fintha A, Steele S, Zhang ZR, Bell PD. Oscillating cortical thick ascending limb cells at the juxtaglomerular apparatus. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1940–1946, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komlosi P, Fintha A, Bell PD. Current mechanisms of macula densa cell signalling. Acta Physiol Scand 181: 463–469, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komlosi P, Fintha A, Bell PD. Unraveling the relationship between macula densa cell volume and luminal solute concentration/osmolality. Kidney Int 70: 865–871, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapointe JY, Laamarti A, Hurst AM, Fowler BC, Bell PD. Activation of Na:2Cl:K cotransport by luminal chloride in macula densa cells. Kidney Int 47: 752–757, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R, Carretero OA, Ren Y, Garvin JL. Increased intracellular pH at the macula densa activates nNOS during tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int 67: 1837–1843, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu R, Garvin JL, Ren Y, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Depolarization of the macula densa induces superoxide production via NAD(P)H oxidase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1867–F1872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malone AM, Anderson CT, Tummala P, Kwon RY, Johnston TR, Stearns T, Jacobs CR. Primary cilia mediate mechanosensing in bone cells by a calcium-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 13325–13330, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology 131: 911–920, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navar LG, Ploth DW, Bell PD. Distal tubular feedback control of renal hemodynamics and autoregulation. Annu Rev Physiol 42: 557–571, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid SA, Imig JD, Harrison-Bernard LM, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. Physiol Rev 76: 425–536, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oppermann M, Hansen PB, Castrop H, Schnermann J. Vasodilatation of afferent arterioles and paradoxical increase of renal vascular resistance by furosemide in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F279–F287, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peti-Peterdi J, Chambrey R, Bebok Z, Biemesderfer D, St. John PL, Abrahamson DR, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Macula densa Na+/H+ exchange activities mediated by apical NHE2 and basolateral NHE4 isoforms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F452–F463, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peti-Peterdi J, Bell PD. Cytosolic [Ca2+] signaling pathway in macula densa cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F472–F476, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peti-Peterdi J, Morishima S, Bell PD, Okada Y. Two-photon excitation fluorescence imaging of the living juxtaglomerular apparatus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F197–F201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peti-Peterdi J. Calcium wave of tubuloglomerular feedback. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F473–F480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J Membr Biol 184: 71–79, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Removal of the MDCK cell primary cilium abolishes flow sensing. J Membr Biol 191: 69–76, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. The renal cell primary cilium functions as a flow sensor. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 517–520, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Fluid flow sensing and triggered nucleotide release in epithelia. J Physiol 586: 2669, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren Y, Carretero OA, Garvin JL. Mechanism by which superoxide potentiates tubuloglomerular feedback. Hypertension 39: 624–628, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satriano J, Wead L, Cardus A, Deng A, Boss GR, Thomson SC, Blantz RC. Regulation of ecto-5′-nucleotidase by NaCl and nitric oxide: potential roles in tubuloglomerular feedback and adaptation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1078–F1082, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlatter E, Salomonsson M, Persson AE, Greger R. Macula densa cells sense luminal NaCl concentration via furosemide sensitive Na+2Cl-K+ cotransport. Pflügers Arch 414: 286–290, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnermann J, Briggs JP. Function of the juxtaglomerular apparatus: control of glomerular hemodynamics and renin secretion. In: The Kidney Physiology and Pathophysiology, edited by Seldin DW, Giebisch G. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2008, p. 589–626 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnermann J, Briggs JP. Tubuloglomerular feedback: mechanistic insights from gene-manipulated mice. Kidney Int 74: 418–426, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sipos A, Vargas SL, Toma I, Hanner F, Willecke K, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexin 30 deficiency impairs renal tubular ATP release and pressure natriuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1724–1732, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sottiurai V, Malvin RL. The demonstration of cilia in canine macula densa cells. Am J Anat 135: 281–286, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thurau K, Schnermann J. The Na concentration of the macula densa cells as a factor regulating glomerular filtration rate (micropuncture studies). 1965. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 925–934, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallon V, Mühlbauer B, Osswald H. Adenosine and kidney function. Physiol Rev 86: 901–940, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vargas SL, Toma I, Kang JJ, Meer EJ, Peti-Peterdi J. Activation of the succinate receptor GPR91 in macula densa cells causes renin release. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1002–1011, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, Carretero OA, Garvin JL. Inhibition of apical Na+/H+ exchangers on the macula densa cells augments tubuloglomerular feedback. Hypertension 41: 688–691, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webber WA, Lee J. Fine structure of mammalian renal cilia. Anat Rec 182: 339–344, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ. Interaction between nitric oxide and oxygen radicals in regulation of tubuloglomerular feedback. Acta Physiol Scand 168: 119–124, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang T, Park JM, Arend L, Huang Y, Topaloglu R, Pasumarthy A, Praetorius H, Spring K, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Low chloride stimulation of prostaglandin E2 release and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in a mouse macula densa cell line. J Biol Chem 275: 37922–37929, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]