Abstract

Although complement activation is known to occur in the setting of severe hemorrhagic shock and tissue trauma (HS/T), the extent to which complement drives the initial inflammatory response and end-organ damage is uncertain. In this study, complement factor 3-deficient (C3−/−) mice and wild-type control mice were subjected to 1.5-h hemorrhagic shock, bilateral femur fracture, and soft tissue injury, followed by 4.5-h resuscitation (HS/T). C57BL/6 mice were also given 15 U of cobra venom factor (CVF) or phosphate-buffered saline injected intraperitoneally, followed by HS/T 24 h later. The results showed that HS/T resulted in C3 consumption in wild-type mice and C3 deposition in injured livers. C3−/− mice had significantly lower serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and circulating DNA levels, together with much lower circulating interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) levels. Temporary C3 depletion by CVF preconditioning also led to reduced transaminases and a blunted cytokine release. C3−/− mice displayed well-preserved hepatic structure. C3−/− mice subjected to HS/T had higher levels of heme oxygenase-1, which has been associated with tissue protection in HS models. Our data indicate that complement activation contributes to inflammatory pathways and liver damage in HS/T. This suggests that targeting complement activation in the setting of severe injury could be useful.

Keywords: systemic inflammatory response syndrome, high-mobility group box 1, single-strand DNA, double-strand DNA, heme oxygenase-1

trauma is the leading cause of death in individuals between 1 and 44 years of age in the United States (16). Up to 40% of the deaths are due to the consequences of trauma-induced hemorrhage shock (HS) (14). Survivors of HS exhibit a systemic inflammatory response associated with end-organ damage and dysfunction. This response is thought to be due to the activation of innate immune mechanisms. For example, we (25) and others (2) have shown that Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 signaling is critical to the HS-trauma (HS/T) inflammatory response. Among the other components of the innate immune system likely to be important to the initial inflammatory response following HS/T is the complement system. Both clinical and animal studies reveal that acute blood loss and trauma activate the complement cascade and complement activation plays a detrimental role in HS (7, 39). The magnitude of complement activation closely correlates with injury severity, development of multiple organ dysfunction, and death (10). However, the role of complement in regulating the initial inflammatory response or liver damage has not been studied.

The complement system consists of ∼35 effectors or regulators. Activation of the complement system mainly occurs via one of three pathways, the classical, alternative, and lectin pathways. Complement factor 3 (C3) activation is the step common to all three pathways. Previous studies have demonstrated that blockade of one or more pathways by C1q, factor B, C4 deficiency, or antagonists provided protection to gut, limb, cardiac, and kidney in models of ischemia-reperfusion injury and that C3 deficiency prevented intestinal, hindlimb, kidney, and liver ischemia-reperfusion injury (6, 9, 33, 34, 37, 42). Here we tested the hypothesis that complement, and specifically C3, is involved in the initial systemic inflammatory response and liver injury induced by HS/T. We show here that C3 deficiency or complement depletion results in an attenuated inflammatory response and a marked reduction in liver damage following HS/T. We also show that C3 deficiency is associated with a marked increase in the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in the liver after HS/T.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Cobra venom factor (CVF) was purchased from Quidel (San Diego, CA). Mouse IL-6 and IL-10 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The mouse C3 ELISA kit was from ALPCO Diagnostics (Salem, NH). Anti-high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and anti-C3 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), and anti-HO-1 antibody was from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). Quant-iT PicoGreen double-strand DNA (dsDNA) Kits and Quant-iT OliGreen single-strand DNA (ssDNA) Kits were bought from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Animal preparation.

Male C3−/− mice (B6.129S4-C3KO) and their wild-type counterparts, C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), were used in this study. All mice were 8–12 wk old and weighed 20–30 g. Animal handling and care complied with the regulations regarding the care and use of experimental animals published by the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. The animals were maintained in the animal facility with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and free access to standard laboratory chow and water.

Hemorrhagic shock.

Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (70 mg/kg). HS was performed as previously described by our group (43). All surgical procedures were performed with the use of aseptic technique. Briefly, bilateral groin dissections were performed. After identification of the femoral artery, a small arteriotomy was made, and the femoral arteries were cannulated with sterile PE-10 catheters. Animals were hemorrhaged to a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 25 mmHg via one femoral artery cannula. The contralateral cannula was used to monitor blood pressure and heart rate throughout the experiment. Sham-operated animals underwent bilateral femoral artery cannulation only. After either 90 min or 120 min of HS, animals were resuscitated with three times the volume of shed blood with Ringer lactate. Throughout the procedure, body temperature was monitored via a rectal temperature probe and maintained at 37°C with a heating pad and a heating lamp.

Bilateral femur fracture and soft tissue injury.

After administration of anesthesia, both femurs were fractured with a hemostat 2–3 mm above the knee joint. Soft tissue injury (STI) was induced by using a hemostat to squeeze thigh muscles adjacent to the fracture for a period of 30 s.

Experimental groups.

To study the effect of complement depletion by CVF in HS we utilized C57BL/6 mice divided into the following four groups: 1) administration of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by anesthesia only; 2) administration of CVF followed by anesthesia only; 3) administration of PBS followed by HS + bilateral femur fracture (BFF) + STI; and 4) administration of CVF followed by HS + BFF + STI.

We further characterized the effect of full complement depletion by using C3−/− mice. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were used as control animals. Animals were divided into the following six groups: 1) anesthesia in wild-type mice; 2) anesthesia in C3−/− mice; 3) bilateral femoral artery cannulation in wild-type mice; 4) bilateral femoral artery cannulation in C3−/− mice; 5) HS + BFF + STI in wild-type mice; and 6) HS + BFF + STI in C3−/− mice.

Complement depletion by CVF.

Complement was depleted by intraperitoneal administration of CVF 24 h before HS. Animals were treated with 15 U of CVF dissolved in PBS (total 200 μl). Control animals received an equal volume of intraperitoneal PBS at the same time point.

Sample collection.

At the conclusion of the experiment, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and blood was harvested by cardiac puncture. Serum was collected by centrifuging the blood at 5,000 revolutions/min for 10 min at 4°C. Serum was divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C until further analysis. The same hepatic lobe was harvested, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C. The liver was also removed and fixed in 10% neutral formalin for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining. For immunofluorescence staining, liver was flushed with PBS and then perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde. After fixation for 2 h, samples were switched to 30% sucrose for 24 h with a total of three times of sucrose changing. The samples were cryopreserved in 2-methylbutane and stored at −80°C until ready for sectioning.

Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase measurement.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured by HESKA Dri-Chem 4000 (HESKA, Loveland, CO; slides from Fujifilm Japan).

C3, IL-6, and IL-10 levels.

Serum C3, IL-6, and IL-10 levels were assessed by ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions.

C3 deposition staining.

Six-micrometer liver sections were incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h, followed by five washes with PBS + 0.5% BSA (PBB). The samples were then incubated with rat polyclonal anti-CD3 (1:1,000, Cederlane) primary antibody for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation in the appropriate Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:250, Invitrogen) and Cy3 (1:1,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) secondary antibodies diluted in PBB. Samples were washed three times with PBB, followed by 30-s incubation with Hoechst nuclear stain. Nuclear stain was removed, and samples were washed with PBS before being coverslipped with Gelvatol. Positively stained cells in six random fields were imaged on a Fluoview 1000 confocal scanning microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY). Imaging conditions were maintained at identical settings within each antibody-labeling experiment with original gating performed with the negative control.

Serum HMGB1 levels and HO-1 in liver tissues.

Western blot analysis was used to assess serum HMGB1 level and HO-1 induction in whole liver. Three microliters of plasma or fifty micrograms of liver homogenate was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked for 1 h in PBS-Tween (0.1%) with 5% milk, followed by immunostaining with optimized dilutions of a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse HMGB1 antibody (1:1,000) or anti-HO-1 (1:2,500) in 1% milk in PBS-Tween overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were given, and membranes were developed with the Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and exposed to film. Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems) was used to quantify each band of HO-1 and β-actin, and their intensity ratios were calculated.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling assay.

Livers were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, followed by a standardized protocol for cryopreservation. Apoptosis was measured by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay with a kit purchased from Promega according to the manufacturer's protocol and counterstained with Hoechst nuclear stain. TUNEL-positive cells were quantitated with a Metamorph image acquisition and analysis system (Chester, PA) incorporating a Nikon microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). TUNEL-positive cells from six random fields per section were then counted in a blinded manner, and the count was expressed as a percentage of the total cell number.

Serum dsDNA and ssDNA detection.

Serum dsDNA and ssDNA levels were detected with Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Kits and Quant-iT OliGreen ssDNA Kits according to the product instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons of two groups under the same treatment were performed by Student's t-test with SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). One-way ANOVA analysis was used for multiple group comparisons. Significance was established at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Complement factor 3 takes part in pathogenesis of hemorrhagic shock and trauma.

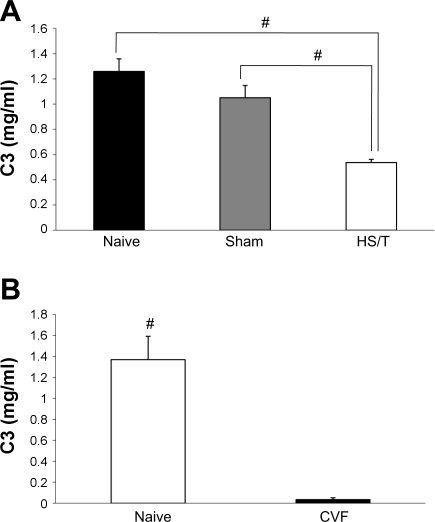

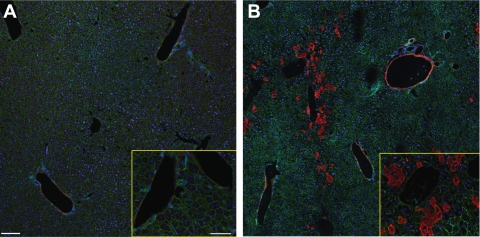

To confirm the activation of complement in our model, and specifically the involvement of C3, at the time point we studied (6 h), we measured circulating C3 levels and tissue deposition. As shown in Fig. 1A, sham-operated mice and unmanipulated control (naïve) mice had no difference in circulating C3 concentration as measured by ELISA. However, compared with C3 levels in naive and sham-operated groups, mice subjected to HS/T had much lower C3 levels (0.54 ± 0.09 mg/ml, P < 0.001). Consistent with the decline in serum C3 values in HS/T mice, immunofluorescence staining showed intense C3 deposition in the sinusoids in the vicinity of the central vein and in the veins (Fig. 2B), while relatively little C3 was detected in the liver of sham-operated (Fig. 2A) or CVF-pretreated mice. There was no detectable C3 in C3−/− mouse liver (data not shown). Although some of the reduction in C3 levels in the HS/T mice could be the result of dilution, in combination these experiments support the contention that complement activation occurs by 6 h in this model.

Fig. 1.

A: complement factor 3 (C3) level comparison. There was no statistical difference in C3 level between naive (n = 6) and sham-operated groups (n = 6) (1.26 ± 0.28 vs. 1.05 ± 0.26 mg/ml, P = 0.058). However, the hemorrhagic shock + tissue trauma (HS/T) group (n = 8) had a much lower C3 level (0.54 ± 0.49 mg/ml; #P < 0.001) than naive and sham-operated groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. B: before and 24 h after cobra venom factor (CVF) treatment, circulating C3 levels dropped from 1.370 ± 0.223 to 0.034 ± 0.017 mg/ml (each n = 5; #P < 0.001). Values are expressed as means ± SE.

Fig. 2.

Complement factor 3 deposition in liver after HS/T. Immunofluorescence staining showed intense C3 deposition in the sinusoids in the vicinity of the central vein and in the veins (×20, ×60; B), while relatively little C3 was detected in the sham-operated liver (×20, ×60; A). Red, C3; green, β-actin; blue, nucleus.

Complement contributes to liver injury.

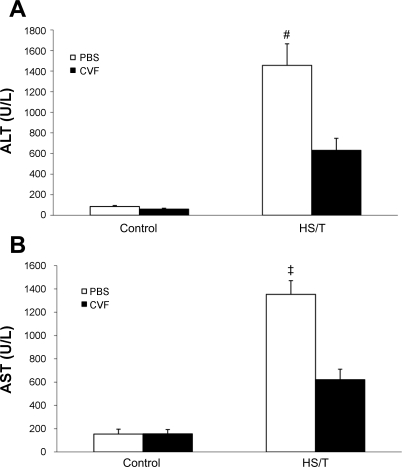

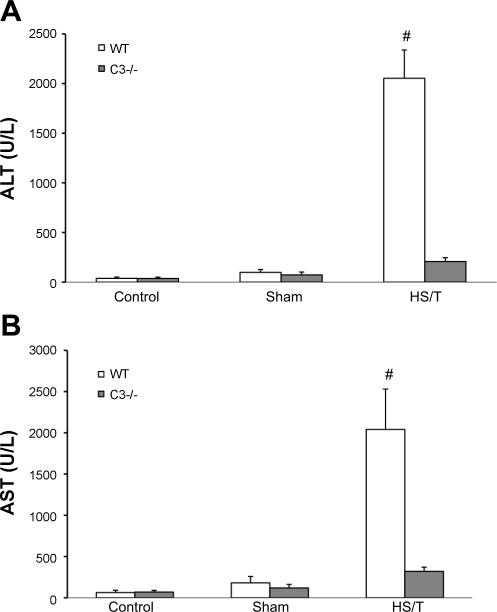

HS with or without associated tissue trauma induces liver damage. To assess the importance of complement in liver injury seen in HS, two approaches were undertaken. First, we pretreated wild-type mice with CVF to deplete complement before HS/T. As shown in Fig. 1B, intraperitoneal CVF pretreatment (24 h) reduced circulating C3 levels from 1.37 ± 0.22 to 0.03 ± 0.02 mg/ml (n = 5, P < 0.01). This is consistent with previous reports that CVF reduces C3 levels to <5% of baseline (24). Second, we also subjected C3−/− mice to HS/T. Liver injury was assessed by both histology and circulating ALT and AST levels. As shown in Fig. 3, depleting complement with CVF resulted in significantly less liver injury as measured by circulating transaminases. Importantly, CVF pretreatment alone did not induce liver injury. The complete absence of C3 resulted in even more dramatic reduction of liver enzymes (Fig. 4). As expected, C3−/− mice exhibited an almost complete absence of HS/T-induced liver damage at the 6 h time point (Fig. 5D), whereas areas of necrosis were readily apparent in wild-type mice subjected to HS/T (Fig. 5B). PBS-pretreated mice had results consistent with wild-type groups, while minimal necrosis was evident in the livers of CVF-pretreated mice (data not shown). Of note, no difference in TUNEL staining was noted among wild-type, CVF-treated, and C3−/− mice after HS (data not shown), suggesting that the induction of apoptosis was not complement dependent.

Fig. 3.

A: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of different groups with or without C3 depletion. There was no statistical difference of serum ALT level in the control groups (each n = 6, P = 0.067). In the HS groups, the CVF pretreatment group had a much lower ALT level (each n = 6; 630.60 ± 116.78 vs. 1,455.61 ± 209.23 U/l; #P = 0.009). Values are expressed as means ± SE. B: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels of different groups. There was no statistical difference between either of the control groups (each n = 6; P = 0.947). However, CVF pretreatment resulted in a lower AST level in HS groups (each n = 6; 620.8 ± 90.06 vs. 1,353.25 ± 118.06 U/l; ‡P = 0.002).

Fig. 4.

A: ALT level comparison in C3−/− and wild-type (WT) mice. There was no statistical difference between anesthesia groups (n = 5) or sham-operated groups (n = 5 and 6, respectively). However, the C3−/− group had a much lower ALT level after HS/T [207.6 ± 38.5 (n = 8) vs. 2,053.4 ± 284.8 U/l (n = 7); #P = 0.003]. Values are expressed as means ± SE. B: AST level comparison in C3−/− and WT mice. There was no statistical difference for AST levels between C3−/− and WT anesthesia or sham-operated mice. However, the C3−/− group (n = 8) had a much lower AST level than WT control mice (n = 7) after HS/T (320.4 ± 50.7 vs. 2,041.2 ± 489.3 U/l; #P = 0.008).

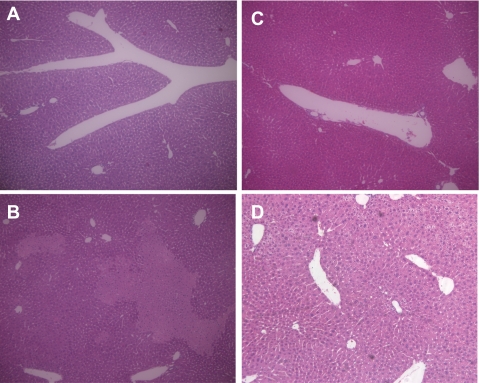

Fig. 5.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining results. A: H & E staining of WT control liver (×100). B: H & E staining of WT mouse liver after HS/T (×100) shows focal hepatic necrosis. C: H & E staining of C3−/− control liver (×100). D: H & E staining of C3−/− mouse liver after HS/T (×100) shows well-preserved histological finding.

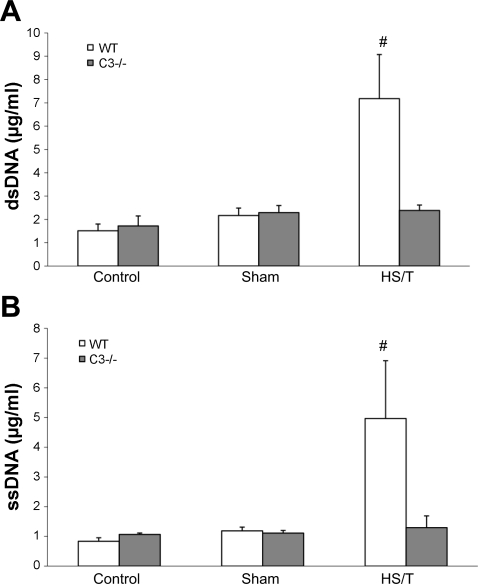

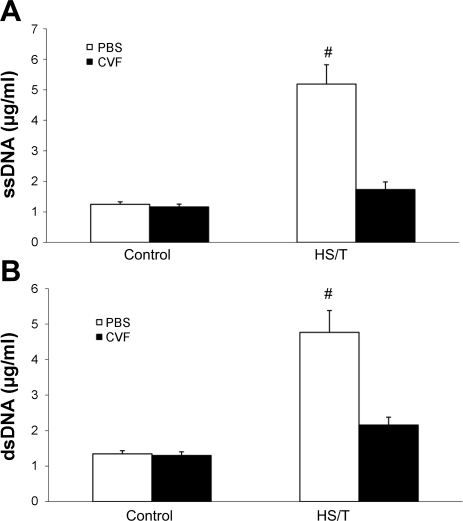

Recent evidence indicates that DNA can be released after tissue trauma (4, 40, 41). Therefore, we also measured levels of plasma ssDNA and dsDNA. Wild-type (Fig. 6) or PBS-treated (Fig. 7) mice subjected to HS/T exhibited marked elevation in both forms of DNA. Again, this was not seen in the absence of C3. CVF treatment also remarkably reduced the release of DNA. Thus complement inhibition also reduced the levels of this marker of tissue injury.

Fig. 6.

A: serum double-strand DNA (dsDNA) comparison between WT and C3−/− groups. There was no statistical difference in circulating dsDNA between WT and C3−/− control groups or sham-operated groups. After HS/T, circulating dsDNA levels in WT (n = 7) and C3−/− (n = 8) groups were 7.18 ± 1.89 vs. 2.38 ± 0.23 μg/ml, respectively (#P = 0.012). There was no statistical difference among the C3−/− groups. However, among the WT groups, the HS/T group had much higher dsDNA level than control and sham-operated groups (P < 0.05), while there was no statistical difference between control and sham-operated groups. B: circulating single-strand DNA (ssDNA) level comparison between WT and C3−/− groups. There was no statistical difference in circulating ssDNA levels between C3−/− and wild-type control (each n = 5) or sham-operated (n = 5 and 6, respectively) groups. After HS/T, circulating ssDNA levels in WT (n = 7) and C3−/− (n = 8) groups were 4.97 ± 1.95 and 1.29 ± 0.40 μg/ml, respectively (#P = 0.002). There was no statistical difference among the C3−/− groups. However, among the WT groups, HS/T mice had a much higher ssDNA level than control and sham mice (P < 0.05). Values are expressed as means ± SE.

Fig. 7.

A: circulating ssDNA level comparison between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and CVF treatment groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE. There was no statistical difference in circulating ssDNA levels between control groups (n = 6; P = 0.749). After HS/T, the circulating ssDNA level in the CVF group was much lower than in the PBS group (n = 6; #P = 0.005). B: serum dsDNA level comparison between PBS and CVF treatment groups. There was no statistical difference in circulating dsDNA between the 2 control groups (n = 6; P = 0.341). After HS/T, the circulating dsDNA level in the PBS group was much higher than in the CVF preconditioning group (n = 6; #P < 0.001).

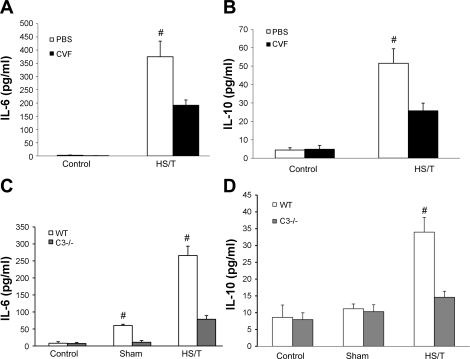

Circulating IL-6 and IL-10 in HS are complement dependent.

HS results in the induction of a systemic inflammatory response manifested by significant increases in circulating cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10. To assess the impact of complement on the initial inflammatory response after HS, circulating IL-6 and IL-10 levels were measured. Depleting complement with CVF resulted in significantly lower IL-6 and IL-10 levels after HS/T compared with the HS/T group treated with PBS (Fig. 8, A and B). The complete absence of C3 resulted in even more dramatic inhibition of systemic inflammation, with IL-6 and IL-10 levels remaining near baseline in the C3−/− mice (Fig. 8, C and D). Interestingly, the absence of C3 also resulted in much lower IL-6 levels in response to the sham manipulation. These observations indicate that C3 is essential to the inflammatory response initiated by either minor tissue trauma or severe HS.

Fig. 8.

A: comparison of IL-6 levels between PBS and CVF groups. There was no statistical difference in IL-6 between PBS and CVF pretreatment groups after anesthesia (each n = 6; P = 0.065). After HS/T, the CVF group had a lower IL-6 level than the PBS group (each n = 6; 191.68 ± 19.90 vs. 374.98 ± 58.92 pg/ml; #P = 0.004). B: comparison of IL-10 levels between PBS and CVF groups. There was no statistical difference in IL-10 between PBS and CVF pretreatment control groups (P = 0.855). After HS/T, the CVF group had a lower IL-10 level than the PBS group (25.72 ± 4.17 vs. 51.53 ± 7.90 pg/ml; #P = 0.023). C: comparison of IL-6 levels in C3−/− mice and WT mice. There was no statistical difference between anesthesia groups (n = 5). In sham-operated groups, C3−/− mice (n = 5) had a lower IL-6 level than WT mice (n = 6; 11.0 ± 5.0 vs. 60.2 ± 3.6 pg/ml; #P < = 0.001). In HS/T groups, C3−/− mice (n = 8) released much less IL-6 than WT mice (n = 7; 78.5 ± 10.8 vs. 265.9 ± 27.5 pg/ml; #P ≤ 0.001). D: comparison of IL-10 levels in C3−/− and WT mice. There was no statistical difference between WT and C3−/− anesthesia or sham-operated groups, while C3−/− mice (n = 8) had lower IL-10 levels than WT mice (n = 7; 14.6 ± 1.8 vs. 33.9 ± 4.4 pg/ml; #P = 0.003). Values are expressed as means ± SE.

C3 is required for increases in circulating HMGB1 in HS.

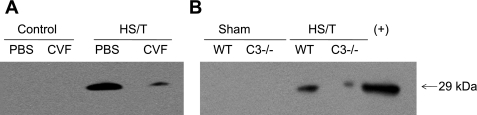

We (18) and others (23) previously showed that HMGB1 is an important mediator of the inflammatory response and end-organ damage in HS and tissue trauma. To assess the importance of C3 on the release of HMGB1 in this model, circulating HMGB1 levels were measured by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 9, HS in wild-type or PBS-treated animals resulted in an increase in detectable HMGB1 in the circulation. However, in the absence of C3 (Fig. 9B) or with CVF preconditioning (Fig. 9A), HMGB1 levels were markedly lower. These observations indicate that C3 activation contributes to the release of large levels of HMGB1 into the circulation in HS.

Fig. 9.

Western blot of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Raw cell lysate was used as HMGB1 positive control. Bands were around 29 kDa. There was no detectable HMGB-1 in either sham-operated or control groups. However, the WT group showed much more serum HMGB1 than C3−/− (B) or CVF-pretreated (A) mice (representative result of 3 independent experiments).

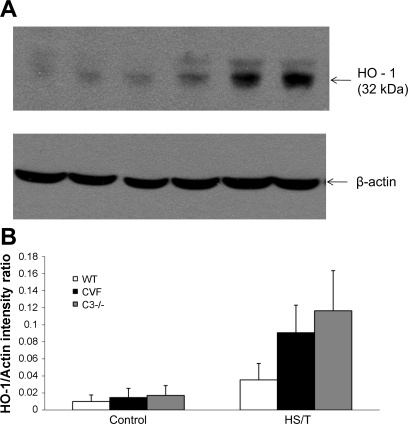

C3 deficiency is associated with exaggerated induction of HO-1 in HS.

HO-1 is an inducible protein in HS, and HO-1 has been shown to be hepatoprotective (29, 30a). Therefore, we postulated that C3 depletion or deficiency might be associated with more HO-1 induction. As shown in Fig. 10, HS induced HO-1 protein in wild-type mice as expected. However, C3−/− or CVF-treated mice subjected to HS exhibited a much greater upregulation of HO-1 at 6 h than seen in wild-type mice. Thus complement activation appears to suppress the upregulation of this protective pathway.

Fig. 10.

A: heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) induction in different groups by Western blot. HO-1 was identified at 32 kDa. Control liver in WT, CVF-pretreated, and C3−/− groups had very little HO-1 induction. HS/T induced HO-1 in WT liver, while CVF and C3−/− groups had more detectable HO-1 (representative result of 3 independent experiments). B: quantification of each band. The intensity ratio of HO-1 to β-actin for each band is shown.

DISCUSSION

Activation of the complement system has been demonstrated in the setting of trauma and HS in both humans (7, 10) and experimental animal models (6, 39). However, the level of importance of the complement system to either the initiation of the inflammatory response or end-organ damage has not been established. Here we used mice deficient in the expression of C3 and complement depletion in wild-type mice to address this question. C3−/− mice were especially useful because C3 is required for all three known pathways of complement activation. We found that complement depletion or deficiency led to a diminished systemic inflammatory response following HS/T as measured by circulating IL-6, IL-10, and HMGB1 levels. This was associated with a reduction in tissue trauma measured by circulating ALT, AST, and DNA levels. The reduced liver damage seen in CVF-preconditioned or C3−/− mice after HS/T was associated with an upregulation of the protective enzyme HO-1. These findings point to the central role of complement in the early systemic responses following HS.

Clinical studies have shown that C3 levels in trauma patients correlate to multiple organ failure (MOF) and mortality (10). In our study, wild-type mice subjected to HS/T exhibited a reduction of circulating C3. The simultaneous accumulation of C3 in the liver suggests that C3 levels drop because of complement activation and deposition. Our results show that the liver is at least one organ susceptible to complement-mediated injury. Because HO-1 is an inducible protein in HS that has been shown to be hepatoprotective (29, 30a), it is possible that the liver protection could be partially related to greater HO-1 induction in CVF-preconditioned and C3−/− mice. With the use of local ischemia-reperfusion, C3 deficiency has also been shown to be protective against gut (34), limb (33), kidney (42), brain (37), and liver (9) injury. CVF can combine with factors B and D to activate C3 without the limitation of factors H or I or complement receptor 1, which results in the temporary depletion of almost all circulating C3 (1, 17, 19). However, unlike the total C3 absence in C3−/− mice, C3 depletion by CVF is incomplete, with ∼5% of circulating C3 remaining (24). In the CVF preconditioning group, ALT and AST elevations were also blunted. These were consistent with previous findings (39). However, even complete C3 deficiency did not result in full protection. Possible explanations include 1) complement activation is only one of the mechanisms leading to organ damage or 2) there is evidence that thrombin (12) and reactive oxygen species can activate complement independent of C3 (5, 26, 31). Therefore, besides C3, other factors or pathways also need to be considered. Although complement depletion or deficiency was associated with less hepatocyte necrosis, we did not find any differences in liver apoptosis at the time point studied. This suggests that the low level of hepatocyte apoptosis in HS/T is not complement dependent.

Both HS and trauma initiate inflammatory cascades, and excessive cytokine production is a key basis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and MOF. Serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels are indicators of the magnitude of the inflammatory response (8, 20, 27). We found that complement deficiency attenuated the IL-6 and IL-10 response, implicating complement as one of the drivers of the initial systemic inflammatory response following HS/T.

HMGB1 is a nuclear protein that can be released by cells in response to stresses such as hypoxia or passively by cells undergoing necrosis (30). Therefore, HMGB1 is a marker of both tissue stress responses and tissue damage. Once released, it plays a vital role in the initiation and propagation of the inflammatory response following trauma and HS and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of trauma, HS, and sepsis both experimentally and clinically (28, 32, 35). Our previous work (18, 30) showed that HMGB1-neutralizing antibodies suppress serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels in models of HS, ischemia-reperfusion, and femur fracture. HMGB1-neutralizing antibodies also ameliorated hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury (2, 15) as well as gut barrier dysfunction (36) and ultimately led to improved survival. Here, we found that C3 depletion or deficiency was associated with lower circulating HMGB1 levels. Whether this is due to a decrease in tissue damage or a role of complement in regulating HMGB1 release is uncertain. However, some of the impact of complement on the systemic inflammatory response could be mediated through HMGB1.

Both laboratory and clinical studies (4, 16a, 39, 41) have shown that shock and trauma can result in cell-free DNA release. Lam et al. (16a) reported that plasma DNA increased within 20 min of injury and was related to severity. Both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can be released in HS (4, 40). Although TLR9 mainly recognizes bacteria ssDNA oligonucleotides containing CpG motifs, mtDNA resembles bacterial DNA in being circular and having nonmethylated CpG motifs (3). Recently Zhang et al. (41) reported that mtDNA in trauma patients could act on polymorphonuclear neutrophils through TLR9. While self-DNA is typically degraded in mammalian lysosomes, a self-DNA release in HS and trauma could result in inflammatory signaling through TLR9 activity or sensed via TLR-independent pathways (13, 22, 38). The marked complement-dependent increases in circulating DNA seen in our study could be the result of tissue damage. Again, whether DNA sensing drives the complement-dependent inflammatory response is unknown. We have seen marked suppression of HS/T-induced inflammation in TLR9 mutant mice (unpublished data), suggesting that DNA can serve as an endogenous trigger of inflammation in our rodent model of HS/T.

In conclusion, our study provides conclusive results showing that complement activation is a central component of the initial response to HS/T. Whether complement also plays adaptive roles in the setting of severe trauma is unknown. However, our results raise the possibility that suppressing complement activation could be beneficial in the setting of severe injury. Complement activation can also contribute to the pathobiology manifested by an exaggerated inflammatory response and end-organ damage.

Perspectives and Significance

Our results show that C3 depletion or deficiency attenuates HS/T related liver injury and systemic inflammation. Therefore, our findings highlight the importance of complement activity in the pathogenesis of HS/T, which may be a potential therapeutic target in the setting of severe injury. Our next steps would discuss the potential cross talk between complement and other pathways known to regulate the inflammatory response in this model (e.g., TLR4).

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant P50-GM-53789.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lauryn Tait, John M. Brumfield, Meihua Bo, Hong Liao, and Richard A. Shapiro for their technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alper CA, Balavitch D. Cobra venom factor: evidence for its being altered cobra C3 (the third component of complement). Science 191: 1275–1276, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barsness KA, Arcaroli J, Harken AH, Abraham E, Banerjee A, Reznikov L, McIntyre RC. Hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury is TLR-4 dependent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R592–R599, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardon LR, Burge C, Clayton DA, Karlin S. Pervasive CpG suppression in animal mitochondrial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 3799–3803, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou CC, Fang HY, Chen YL, Wu CY, Siao FY, Chou MJ. Plasma nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA as prognostic markers in corrosive injury patients. Dig Surg 25: 300–304, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collard CD, Agah A, Stahl GL. Complement activation following reoxygenation of hypoxic human endothelial cells: role of intracellular reactive oxygen species, NF-kappaB and new protein synthesis. Immunopharmacology 39: 39–50, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diepenhorst GM, van Gulik TM, Hack CE. Complement-mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury: lessons learned from animal and clinical studies. Ann Surg 249: 889–899, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fruchterman TM, Spain DA, Wilson MA, Harris PD, Garrison RN. Complement inhibition prevents gut ischemia and endothelial cell dysfunction after hemorrhage/resuscitation. Surgery 124: 782–791, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebhard F, Pfetsch H, Steinbach G, Strecker W, Kinzl L, Bruckner UB. Is interleukin 6 an early marker of injury severity following major trauma in humans? Arch Surg 135: 291–295, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He S, Atkinson C, Qiao F, Cianflone K, Chen X, Tomlinson S. A complement-dependent balance between hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury and liver regeneration in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 2304–2316, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecke F, Schmidt U, Kola A, Bautsch W, Klos A, Köhl J. Circulating complement proteins in multiple trauma patients: correlation with injury severity, development of sepsis, and outcome. Crit Care Med 25: 2015–2024, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire SR, Lambris JD, Warner RL, Flierl MA, Hoesel LM, Gebhard F, Younger JG, Drouin SM, Wetsel RA, Ward PA. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med 12: 682–687, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii KJ, Coban C, Kato H, Takahashi K, Torii Y, Takeshita F, Ludwig H, Sutter G, Suzuki K, Hemmi H, Sato S, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol 7: 40–44, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma 60: S3–S11, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JY, Park JS, Strassheim D, Douglas I, Diaz del Valle F, Asehnoune K, Mitra S, Kwak SH, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. HMGB1 contributes to the development of acute lung injury after hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L958–L965, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep 56: 1–120, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Lam NY, Rainer TH, Chan LY, Joynt GM, Lo YM. Time course of early and late changes in plasma DNA in trauma patients. Clin Chem 49: 1286–1291, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesavre PH, Hugli TE, Esser AF, Müller-Eberhard HJ. The alternative pathway C3/C5 convertase: chemical basis of factor B activation. J Immunol 123: 529–534, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy RM, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Kaczorowski DJ, Vallabhaneni R, Liu S, Tracey KJ, Lotze MT, Hackam DJ, Fink MP, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Systemic inflammation and remote organ injury following trauma require HMGB-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1538–R1544, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller-Eberhard HJ, Fjellström K. Isolation of the anticomplementary protein from cobra venom and its mode of action on C3. J Immunol 107: 1666–1672, 1971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neidhardt R, Keel M, Steckholzer U, Safret A, Ungethuem U, Trentz O, Ertel W. Relationship of interleukin-10 plasma levels to severity of injury and clinical outcome in injured patients. J Trauma 42: 863–870, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okabe Y, Kawane K, Akira S, Taniguchi T, Nagata S. Toll-like receptor-independent gene induction program activated by mammalian DNA escaped from apoptotic DNA degradation. J Exp Med 202: 1333–1339, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ombrellino M, Wang H, Ajemian MS, Talhouk A, Scher LA, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. Increased serum concentrations of high-mobility-group protein 1 in haemorrhagic shock. Lancet 354: 1446–1447, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pepys MB. Studies in vivo of cobra factor and murine C3. Immunology 28: 369–377, 1975 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prince JM, Levy RM, Yang R, Mollen KP, Fink MP, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling mediates hepatic injury and systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic shock. J Am Coll Surg 202: 407–417, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shingu M, Nonaka S, Nobunaga M, Ahamadzadeh N. Possible role of H2O2-mediated complement activation and cytokines-mediated fibroblasts superoxide generation on skin inflammation. Dermatologica 179: S107–S112, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stensballe J, Christiansen M, Tønnesen E, Espersen K, Lippert FK, Rasmussen LS. The early IL-6 and IL-10 response in trauma is correlated with injury severity and mortality. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53: 515–521, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunden-Cullberg J, Norrby-Teglund A, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala H, Herman G, Tracey KJ, Lee ML, Andersson J, Tokics L, Treutiger CJ. Persistent elevation of high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 33: 564–573, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi T, Shimizu H, Morimatsu H, Maeshima K, Inoue K, Akagi R, Matsumi M, Katayama H, Morita K. Heme oxygenase-1 is an essential cytoprotective component in oxidative tissue injury induced by hemorrhagic shock. J Clin Biochem Nutr 44, 28–40, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, Yang H, Li J, Tracey KJ, Geller DA, Billiar TR. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J Exp Med 201: 1135–1143, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Vallabhaneni R, Kaczorowski DJ, Yaakovian MD, Rao J, Zuckerbraun BS. Heme oxygenase 1 protects against hepatic hypoxia and injury from hemorrhage via regulation of cellular respiration. Shock 33: 274–281, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Zabern WV, Hesse D, Nolte R, Haller Y. Generation of an activated form of human C5 (C5b-like C5) by oxygen radicals. Immunol Lett 14: 209–215, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285: 248–251, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiser MR, Williams JP, Moore FD, Jr, Kobzik L, Ma M, Hechtman HB, Carroll MC. Reperfusion injury of ischemic skeletal muscle is mediated by natural antibody and complement. J Exp Med 183: 2343–2348, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams JP, Pechet TT, Weiser MR, Reid R, Kobzik L, Moore FD, Jr, Carroll MC, Hechtman HB. Intestinal reperfusion injury is mediated by IgM and complement. J Appl Physiol 86: 938–942, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Wang H, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton MJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 296–301, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang R, Harada T, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Levy RM, Englert JA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Harbrecht BG, Billiar TR, Fink MP. Anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody ameliorates gut barrier dysfunction and improves survival after hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med 12: 105–114, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang S, Nakamura T, Hua Y, Keep RF, Younger JG, He Y, Hoff JT, Xi G. The role of complement C3 in intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26: 1490–1495, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasuda K, Yu P, Kirschning CJ, Schlatter B, Schmitz F, Heit A, Bauer S, Hochrein H, Wagner H. Endosomal translocation of vertebrate DNA activates dendritic cells via TLR9-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol 174: 6129–6136, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younger JG, Sasaki N, Waite MD, Murray HN, Saleh EF, Ravage ZB, Hirschl RB, Ward PA, Till GO. Detrimental effects of complement activation in hemorrhagic shock. J Appl Physiol 90: 441–446, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Mitochondrial DNA is released by shock and activates neutrophils via p38 MAP-kinase. Shock 34: 55–59, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464: 104–107, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou W, Farrar CA, Abe K, Pratt JR, Marsh JE, Wang Y, Stahl GL, Sacks SH. Predominant role for C5b-9 in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 105: 1363–1371, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuckerbraun BS, McCloskey CA, Gallo D, Liu F, Ifedigbo E, Otterbein LE, Billiar TR. Carbon monoxide prevents multiple organ injury in a model of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Shock 23: 527–532, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]