Abstract

We used the whole cell patch-clamp technique to investigate the regulation of descending vasa recta (DVR) pericyte Ca2+-dependent Cl− currents (CaCC) by cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca]CYT), voltage, and kinase activity. Murine CaCC increased with voltage and electrode Ca2+ concentration. The current saturated at [Ca]CYT of ∼1,000 nM and exhibited an EC50 for Ca2+ of ∼500 nM, independent of depolarization potential. Activation time constants were between 100 and 200 ms, independent of electrode Ca2+. Repolarization-related tail currents elicited by stepping from +100 mV to varying test potentials exhibited deactivation time constants of 50–200 ms that increased with voltage when electrode [Ca]CYT was 1,000 nM. The calmodulin inhibitor N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide hydrochloride (W-7, 30 μM) blocked CaCC. The myosin light chain kinase blockers 1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine hydrochloride (ML-7, 1–50 μM) and 1-(5-chloronaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine hydrochloride (ML-9, 10 μM) were similarly effective. Resting pericytes were hyperpolarized by ML-7. Pericytes exposed to ANG II (10 nM) depolarized from a baseline of −50 ± 6 to −29 ± 3 mV and were repolarized to −63 ± 7 mV by exposure to 50 μM ML-7. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase inhibitor KN-93 reduced pericyte CaCC only when it was present in the electrode and extracellular buffer from the time of membrane break-in. We conclude that murine DVR pericytes are modulated by [Ca]CYT, membrane potential, and phosphorylation events, suggesting that Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance may be a target for regulation of vasoactivity and medullary blood flow in vivo.

Keywords: kidney, medulla, microcirculation, electrophysiology, vasoconstriction

descending vasa recta (DVR) are 10- to 15-μm-ID microvessels that arise from juxtamedullary efferent arterioles to supply the renal medulla with blood flow. They are terminal resistance vessels with properties that accommodate their dual roles in blood flow regulation and countercurrent exchange (28, 37). Contractility is imparted by remnant smooth muscle cells (pericytes) (39) and modulated by a monolayer of continuous endothelia. DVR traverse the outer medulla sequestered into vascular bundles in a radial arrangement, such that vessels in the center of the bundle perfuse the inner medulla of the kidney and those on the periphery give rise to the capillary plexus, which supplies the outer medullary interbundle region (25, 28). Much interest has been focused on control of regional perfusion of the medulla, because it has been linked to optimization of urinary concentration, salt balance, and control of arterial blood pressure (9, 10, 14, 15).

We previously reported that DVR contraction is regulated by voltage-gated Ca2+ entry into pericytes. Specifically, we showed that depolarization gates Ca2+ entry (55), that vasoconstrictors (ANG II, endothelin-1, and vasopressin) depolarize the cells (4, 34, 35, 54), and that depolarization is mediated by a combination of Cl− channel activation and K+ channel inhibition (4, 34). In particular, ANG II activates an outwardly rectifying Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance that rapidly depolarizes the membrane toward the equilibrium potential of Cl−. Concomitantly, over a longer time period, K+ conductances are suppressed (34). The primacy of Cl− in that scheme has been demonstrated; an increase in the equilibrium potential of Cl− by extracellular anion substitution intensifies DVR contraction, and blockade of Ca2+-dependent Cl− current (CaCC) provides vasodilation (54).

The pivotal role of pericyte Cl− conductance in generation of DVR contraction suggests that it could be a prime target for regulation. In this study, we examined the characteristics of murine DVR pericyte Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance with respect to Ca2+ and voltage dependence and tested its sensitivity to blockade of phosphorylation. Murine CaCC exhibits voltage-dependent activation and is Ca2+-dependent, with an EC50 of ∼500 nM and activation time constant (τ) between 100 and 200 ms. Moreover, blockers of kinase activity inhibit Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance and reverse pericyte depolarization by ANG II, suggesting plausible regulation of blood flow through signaling cascades that regulate channel or accessory protein phosphorylation.

METHODS

Tissue harvest and microvessel isolation.

All investigations involving animal use were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland. Anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The abdomen was opened and the kidneys were excised, leading to euthanasia by exsanguination. The tissue was harvested from C57BL/6 mice (20–30 g; Charles River), sliced, and stored at 4°C in a physiological saline solution [PSS, in mM: 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4)] at room temperature. Small wedges of renal medulla were separated from kidney slices by dissection and transferred to Blendzyme 1 (0.27 mg/ml) in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen), incubated at 37°C for 40 min, transferred to PSS, and stored at 4°C. At intervals, DVR were isolated from the enzyme-digested renal tissue by microdissection under a stereomicroscope and transferred to a perfusion chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope. A micropipette was used to capture the vessels and position them near the entrance region of the chamber. They were oriented so that their axis was perpendicular to the approach of the patch-clamp pipettes. Pericytes were identified on the abluminal surface for formation of patch-clamp gigaseals. Photomicrographs of the vessels and description of the patch-clamp procedure are provided elsewhere (35, 49).

Whole cell patch-clamp recording.

Pericyte membrane potential and whole cell currents were monitored by patch clamp of the cells on isolated vessels at room temperature (34, 35). Recordings were made with a CV201AU headstage and Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Membrane potential was sampled at 10 Hz and whole cell currents at 2 kHz. Electrical access for whole cell current recording was accomplished with ruptured patches using 4- to 8-MΩ-resistance pipettes established on abluminal pericytes of explanted vessels (35). Cell-to-cell coupling is sometimes observed when pericytes are accessed for electrical recording, manifest by prolonged capacitance transients. The underlying endothelium is always highly coupled as a syncytium. We previously characterized gap junction coupling and demonstrated expression of several connexin isoforms in the pericytes and endothelium (49). In the present study, when such coupling was observed in the pericyte, study of the cell was abandoned. The mean cell capacitance (Cm = 12.4 ± 0.5 pF, n = 43 cells) of murine pericytes was virtually identical to that previously documented in the rat (Cm = 12.2 ± 0.5 pF, n = 94). Similarly, access resistance in murine pericytes was similar to that previously obtained in the rat, typically 7–20 MΩ (53). Cl− currents were isolated by inhibition of K+ conductance with Cs+, glibenclamide, and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEACl). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 115 CsMeSO4, 30 CsCl, 10 TEACl, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 2 MgATP (pH 7.2). Free Ca2+ concentration in the electrode, for equilibration with the pericyte cytoplasm, was adjusted by addition of CaCl2 to 10 mmol/l EGTA as determined using the Winmaxc program (http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/), as previously described (36). The results were cross-checked and agreed well with iterative algebraic calculations using a spreadsheet program based on the approach of Tsien and Pozzan (44). During whole cell Cl− current recordings, the extracellular buffer contained 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM TEACl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 10 μM glibenclamide (pH 7.4).

In the case of pericyte membrane potential measurements, recordings were performed in current-clamp (I = 0) mode, with nystatin used as the pore-forming agent (perforated patches), as previously described (22, 35). The pipette contained 120 mM potassium aspartate, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES 10 (pH 7.2), and nystatin (100 μg/ml with 0.1% DMSO) in ultrapure water. The extracellular solution was PSS (see above). Nystatin was dissolved in DMSO, and the excess was discarded daily. Nystatin stock was dispersed into the potassium aspartate pipette solution at 37°C by vigorous vortexing for 1 min; then it was protected from light and backfilled into pipettes via a 0.2-μm filter. Junction and Donnan potentials were corrected as previously described (30, 35).

Reagents.

Nystatin, N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide hydrochloride (W-7), 1-(5-iodonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine hydrochloride (ML-7), 1-(5-chloronaphthalene-1-sulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine hydrochloride (ML-9), N-[2-[[[3-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-propenyl]methylamino]methyl]phenyl]-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methoxybenzenesulfonamide (KN-93), and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Liberase Blenzyme 1 was obtained from Roche Applied Science. Blendzyme was stored in 40-μl aliquots of 4.5 mg/ml in water and diluted into high-glucose DMEM on the day of the experiment. Stock reagents were thawed once, and the excess was discarded each day.

Statistics.

Values are means ± SE. The significance of differences between means was calculated using Student's t-test (paired or unpaired, as appropriate) and analysis of variance. In some figures, data sampled at 10 Hz were averaged 10 values at a time for display at 1 Hz.

RESULTS

Voltage and Ca2+ dependence.

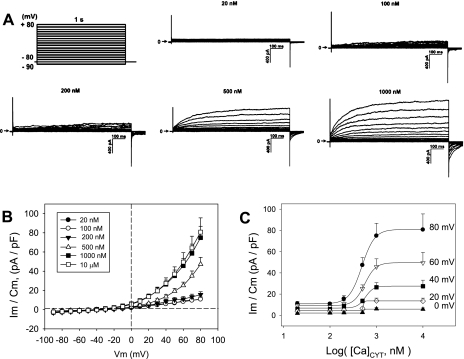

We quantified the voltage and Ca2+ dependence of the murine DVR pericyte whole cell CaCC. Intracellular cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca]CYT) was controlled by dialysis of Ca2+/EGTA-buffered pipette solutions through ruptured patches to achieve nominal values of 20, 100, 200, 500, 1,000, and 10,000 nM. Cells were held at −80 mV and stepped between −90 and +80 mV in 10-mV increments for 1 s at each pulse level. The interpulse interval was 10 s. Cellular currents elicited at various [Ca]CYT (n = 6–9 cells in each group) are shown in Fig. 1A. The trace at [Ca]CYT of 10 μM has been omitted for clarity, because it nearly overlaps the data obtained at 1,000 nM. A summary of end-pulse current normalized to cell capacitance as a function of pulse potential is shown in Fig. 1B. Currents were strongly voltage-dependent, increasing with [Ca]CYT of 200–1,000 nM. As shown in Fig. 1C, half-maximal activation, estimated by Levenburg-Marquardt fit to the four-parameter Hill equation, Im = y0 + a([Ca]CYT)b/{Cb + ([Ca]CYT)b}, where y0 is the current at [Ca]CYT = 0, a and b are constants, and C is the EC50 value of [Ca]CYT that yields half-maximal current. The EC50 was ∼500 nM at all activating potentials between 0 and +80 mV (485, 558, 579, 519, and 529 nM at 0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 mV, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ and voltage dependence of murine descending vasa recta (DVR) pericyte Ca2+-dependent Cl− current (CaCC). A: pulse protocol used to measure CaCC activation (top left). Pericytes were held at −80 mV and depolarized to various test potentials for 1,000 ms. Traces show outwardly rectifying CaCC elicited with electrode Ca2+/EGTA solutions chosen to yield cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca]CYT) of 20, 100, 200, 500, or 1,000 nM. Horizontal arrows indicate zero current level. B: end-pulse membrane current (Im) normalized to cell capacitance (Cm) vs. test potential [membrane potential (Vm)] for [Ca]CYT between 20 nM and 10 μM. C: summary of end-pulse current vs. [Ca]CYT illustrates that EC50 was ∼500 nM independent of activating test potential.

Activation τ.

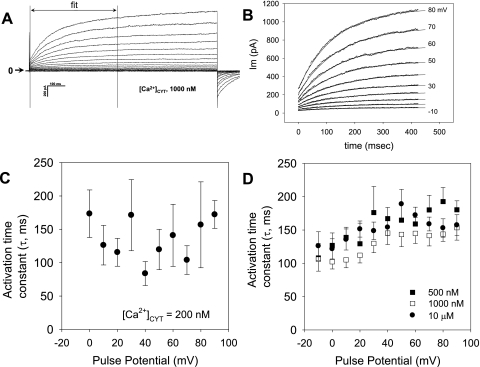

The rate of CaCC activation after membrane depolarization was quantified by fitting 400 ms of whole cell current following the end of the capacitance transient (Fig. 2A). The data fit well to a single exponential (Fig. 2B). The mean activation τ values so obtained are shown in Fig. 2C ([Ca]CYT of 200 nM) and Fig. 2D ([Ca]CYT of 500, 1,000, and 10,000 nM). At [Ca]CYT of 200 nM, currents were small, and fits to the data were variable, yielding τ between 100 and 200 ms. At higher electrode [Ca]CYT of 1,000 nM, exponential fits were more robust and yielded τ in the same range. No relationship of τ to electrode [Ca]CYT was observed. Above a pulse potential of 20 mV, there was also no relationship between τ and voltage. In contrast, with electrode [Ca]CYT of 1,000 nM, there was some tendency for τ to be lower (faster) when potentials were between −10 and +20 mV. Differences between τ at various potentials failed to achieve significance, except for two pairs: P < 0.05 for −20 vs. +80 mV at [Ca]CYT of 500 nM and for −20 vs. +50 mV at [Ca]CYT of 10,000 nM.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+ and voltage dependence of murine CaCC activation. A and B: individual records from which the first 400 ms of data were fit to a single exponential to yield activation time constant (τ). Horizontal arrow indicates zero current level. C and D: summaries of activation τ vs. pulse potential at electrode [Ca]CYT of 200, 500, 1,000 and 10,000 nM.

Conductance and deactivation τ.

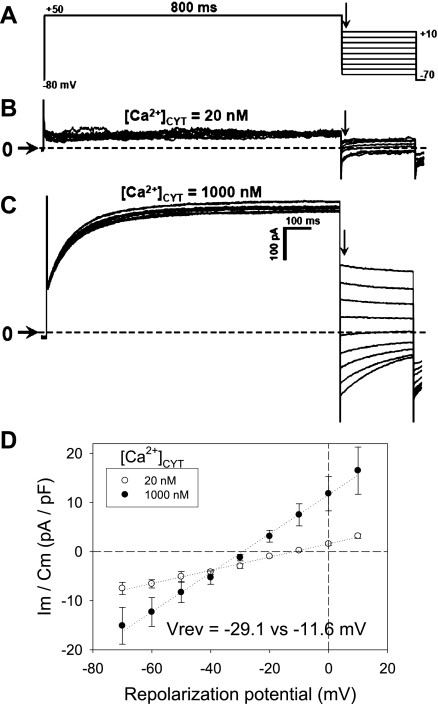

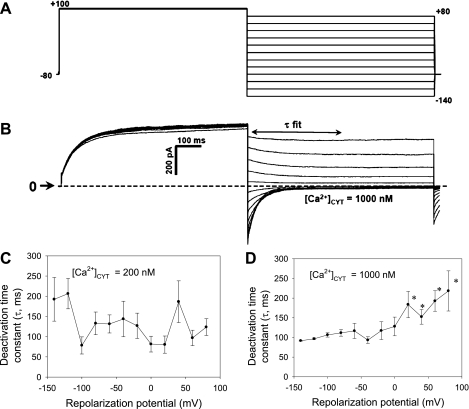

To study Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance and deactivation following repolarization, “tail current” protocols were executed. In a first series of experiments, CaCC were activated by a uniform step depolarization from the holding potential (−80 mV) to +50 mV for 800 ms (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, the cells were repolarized to −70 to +10 mV. The CaCC after the repolarization capacitance transient (arrows in Fig. 3, B and C) was quantified to measure conductance and reversal potential. Whole cell currents were low when electrode buffer contained [Ca]CYT of 20 nM but robust when [Ca]CYT was increased to 1,000 nM. At high [Ca]CYT, the expected shift of the reversal potential toward the equilibrium potential of Cl− occurred, and conductance rose from 1.7 ± 0.4 nS at [Ca]CYT of 20 nM to 5.5 ± 1.7 nS at [Ca]CYT of 1,000 nM. In a separate series of experiments, the deactivation τ was quantified. A tail current protocol (Fig. 4A) was executed with electrode [Ca]CYT of 200 nM to obtain threshold activation of the CaCC or with electrode [Ca]CYT of 1,000 nM to obtain full activation. Pericytes were depolarized to a conditioning potential (+100 mV, 800 ms) and then repolarized to +80 to −140 mV in 20-mV increments. The deactivation τ was calculated by fitting the repolarization currents (Fig. 4B) to a single exponential. As summarized in Fig. 4C, when [Ca]CYT was 200 nM to achieve threshold activation, the exponential fits to calculate τ were somewhat erratic, and a correlation with voltage or [Ca]CYT was not apparent. In contrast, when [Ca]CYT was 1,000 nM and currents were large, an inverse correlation between voltage and the deactivation τ was demonstrated (Fig. 4D; P < 0.05 vs. −140 mV).

Fig. 3.

Conductance of murine CaCC. A: protocol used to measure Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance. Pericytes were held at −80 mV and activated by depolarization to +50 mV for 800 ms. Subsequently, cells were repolarized to test potentials between +10 and −70 mV. B and C: current traces obtained with electrode [Ca]CYT of 20 or 1,000 nM. Horizontal arrows and dashed lines indicate zero current level. D: normalized membrane current vs. repolarization potential, measured immediately after decay of capacitance transient (vertical arrows in A–C), yields slope conductance and reversal potential (Vrev) when electrode [Ca]CYT is 20 or 1,000 nM. Vrev shifted toward Nernst potential of Cl− when [Ca]CYT was raised.

Fig. 4.

Ca2+ and voltage dependence of murine CaCC deactivation. A: protocol used to measure CaCC deactivation. Pericytes were held at −80 mV and activated by depolarization to +100 mV for 800 ms. Subsequently, cells were repolarized to test potentials between +80 and −140 mV. B: deactivation τ obtained by fitting repolarization currents measured after capacitance transient (τ fit) to a single exponential. C and D: deactivation τ vs. repolarization potential when electrode Ca2+ was 200 or 1,000 nM. When [Ca]CYT was 1,000 nM, deactivation τ increased with voltage.

Kinase-dependent regulation of CaCC.

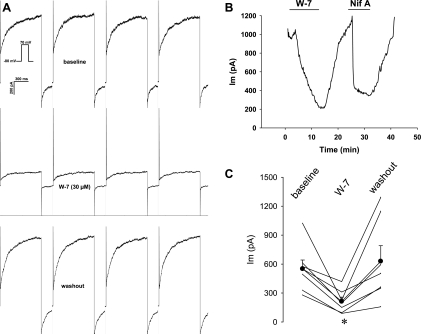

Regulation of CaCC by phosphorylation has been described previously (18, 42, 48, 51, 52). To test whether the murine DVR pericyte currents are similarly modulated, we examined the ability of kinase inhibitors to alter whole cell currents during repetitive pulse depolarizations. With use of an electrode solution buffered to yield [Ca]CYT of 500 nM, whole cell currents were repeatedly elicited at 10-s intervals by depolarization of the cells from the holding potential (−80 mV) to +70 mV for 1 s. We first tested the effects of the calmodulin (CaM) blocker W-7 (30 μM). After the baseline was recorded (Fig. 5A), W-7 was introduced into the extracellular buffer and then removed. W-7 and the CaCC blocker niflumic acid (100 μM) reversibly inhibited CaCC (Fig. 5B). The data obtained from seven cells are summarized in Fig. 5C.

Fig. 5.

Blockade of murine CaCC by the calmodulin inhibitor W-7. A: pericytes were held at −80 mV and sequentially depolarized to +70 mV for 1,000 ms at 10-s intervals (inset). Concatenated examples (interpulse intervals omitted) of currents elicited during depolarizations at baseline, during exposure to W-7 (30 μM), and at washout are shown. B: end-pulse current as a function of time during exposure to W-7 followed by the CaCC inhibitor niflumic acid (100 μM, Nif A). Inhibition by either blocker was reversible. C: summary of end-pulse CaCC before, during, and after exposure to W-7 (n = 7). *P < 0.05 vs. baseline.

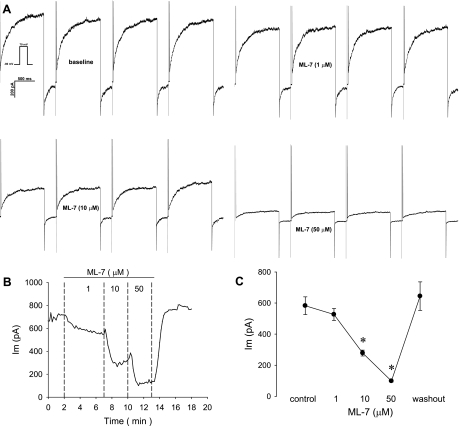

The ability of the putative myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) blocker ML-7 to affect CaCC was also studied with sequential depolarizations (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6, 1–50 μM ML-7 was highly effective and reversible. Similar results were obtained with ML-9 (10 μmol/l), which reduced the depolarization-induced CaCC from 814 ± 99 to 562 ± 80 pA (n = 15 cells, P < 0.05; data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Blockade of murine CaCC by the myosin light chain kinase inhibitor ML-7. A: pericytes were held at −80 mV and sequentially depolarized to +70 mV for 1,000 ms at 10-s intervals (inset). Concatenated examples (interpulse intervals omitted) of currents elicited during depolarizations at baseline and during exposure to ML-7 (1, 10, and 50 μM) are shown. B: end-pulse current as a function of time during exposure to ML-7. Inhibition was concentration-dependent and reversible. C: summary of end-pulse current before, during, and after exposure to increasing concentrations of ML-7 (n = 6). *P < 0.05 vs. baseline (control).

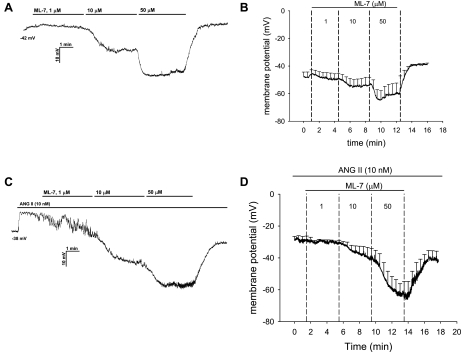

Reversal of ANG II-induced pericyte depolarization by ML-7.

We tested whether ANG II (10 nM) depolarizes murine pericytes and whether CaCC inhibition with ML-7 repolarizes the membrane. Membrane potential was continuously recorded using nystatin perforated patches as ML-7 was added to the bath in increasing concentrations. Figure 7A shows a recording in which the effect of ML-7 on resting potential was investigated, and Fig. 7B summarizes results for five cells. ML-7, at 1, 10, and 50 μM, reversibly hyperpolarized resting cells from −48 ± 3 mV to −50 ± 4 [P = not significant (NS)], −54 ± 6 (P = NS), and −60 ± 7 mV (P < 0.05 vs. baseline), respectively. As in the rat, murine pericytes always depolarized when exposed to ANG II (35), from a baseline of −50 ± 6 to −29 ± 3 mV (P < 0.01, n = 6). Subsequent introduction of increasing concentrations of ML-7 also repolarized ANG II-stimulated cells (Fig. 7, C and D) to −31 ± 2 (1 μM, P = NS), −39 ± 6 (10 μM, P < 0.05 vs. ANG II alone), and −63 ± 7 mV (50 μM, P < 0.01), values that were often below their original resting potential. The effect of ML-7 on membrane potential reversed after washout (to −40 ± 7 mV, P < 0.01 for washout vs. 50 μM ML-7).

Fig. 7.

Repolarization of ANG II-stimulated murine pericytes by ML-7. A and B: example and summary (n = 5) of nystatin perforated-patch recording of pericyte membrane potential at baseline followed by sequential addition of ML-7 to the extracellular buffer at 1, 10, and 50 μM. C and D: example and summary (n = 6) of membrane potential recording during exposure to ANG II (10 nM) followed by sequential, concomitant addition of ML-7 at 1, 10, and 50 μM. Values are means ± SE; most error bars are suppressed for clarity. ML-7 hyperpolarized resting pericytes and reversibly repolarized ANG II-stimulated cells.

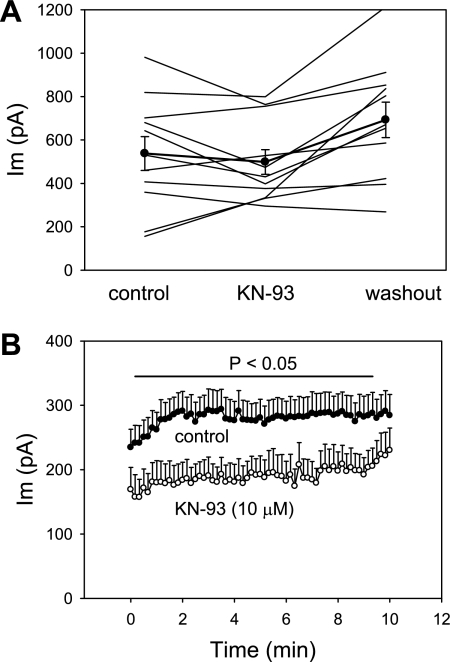

Blockade of CaCC by KN-93.

CaCC activity in some cells has been found to be affected by CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (2, 18, 29, 29, 46). We tested whether the putative CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 (10 μM) can inhibit DVR pericyte CaCC. In a first series of experiments, using electrode [Ca]CYT of 500 nM and a sequential pulse protocol identical to that illustrated in Fig. 5A, KN-93 was introduced into and then removed from the extracellular buffer. As shown in Fig. 8A, some cells appeared to show reversible inhibition, but the results were inconsistent (P = 0.18 for KN-93 vs. control). In a second series of experiments, we included KN-93 or vehicle in the electrode and extracellular buffer from the time of ruptured patch “break-in.” As illustrated in Fig. 8B, the end-pulse whole cell current was significantly lower in KN-93. Moreover, the tendency for currents to increase for several minutes after break-in was absent in KN-93-treated cells.

Fig. 8.

Blockade of murine CaCC by the Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II inhibitor KN-93. A: end-pulse currents wherein pericytes were held at −80 mV and sequentially depolarized to +70 mV for 1,000 ms at 10-s intervals at baseline and as KN-93 (10 μM) was added to and removed from extracellular buffer. Significant suppression of CaCC was not observed. B: KN-93 (10 μM, n = 8) or vehicle (n = 13) was included in the electrode and extracellular buffer from the time of patch formation and break-in. Currents were recorded with the same pulse protocol and subjected to group comparison. Controls illustrate early activation of CaCC immediately after break-in. KN-93 reduced whole cell current (P < 0.05 vs. control for all except the first and last five pulses) and tended to eliminate the early increase of current following break-in.

DISCUSSION

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (CaV) are functionally present in DVR pericytes (53, 55), and all vasoconstrictors thus far tested depolarize those cells (4, 35, 40). Depolarization, in particular, implicates CaV as an entry route, because, without a voltage-gated increase in Ca2+ conductance, a rise in membrane potential diminishes electrochemical driving force for Ca2+ entry. Hence, with acceptance of an important role for CaV, delineation of the channel architecture that regulates membrane potential becomes an issue of parallel importance. Pericytes are held at low resting potentials by K+ conductance and basal, ouabain-sensitive, electrogenic Na+/K+ exchange (3, 34) and depolarized by CaCC activation (35). The functional importance of that depolarization has been verified: raising the Nernst potential of Cl− by ion substitution enhances DVR contraction, and, conversely, inhibition of Cl− conductance induces vasodilation (54). Hence, studies to date point strongly toward a pivotal role for modulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance in DVR contraction, so that the regulation of CaCC activity is of fundamental interest.

A probable sequence of events following contractile agonist stimulation involves store release of Ca2+ by inositol trisphosphate, leading to a rapid increase of CaCC activity that depolarizes the membrane to gate CaV-mediated Ca2+ entry. Such depolarization may be oscillatory, as CaCC tracks [Ca]CYT changes that follow movement of Ca2+ into and out of stores via Ca2+-ATPase, ryanodine, and inositol trisphosphate receptors, respectively. A detailed mathematical simulation of membrane potential changes and intracellular Ca2+ trafficking based on DVR pericyte properties has been recently provided (12).

To examine the characteristics of CaCC, we studied their behavior when exposed to physiological, as well as supraphysiological saturating, [Ca]CYT (1 and 10 μmol/l). We also used voltage clamp to raise membrane potential to high values to activate CaCC and examine rectification. Those efforts revealed strong outward rectification independent of [Ca]CYT and Kd for Ca2+ of ∼500 nM. The latter is consistent with episodic stimulation via subplasmalemmal Ca2+ release (12, 50).

CaCC, studied in different cell types, show variation of properties. In our hands, conductance of CaCC activated at [Ca]CYT thresholds of ∼200 nM and saturated at ∼1,000 nM. The independence of the EC50 for Ca2+ and membrane potential contrasts with observations in other cells where the dependence of activation on Ca2+ declines at high pulse potentials (1, 27, 32). Also, in some preparations, rectification declines at high [Ca]CYT (13, 19, 27). In DVR pericytes, outward rectification is strong at all [Ca]CYT. Some investigators observed a dependence of activation kinetics on voltage and Ca2+ (31, 32), whereas others cite voltage independence at <1 μM Ca2+ (19). In contrast, we observe a lack of dependence on electrode Ca2+ and some tendency for activation to be faster at low pulse potentials. With regard to the latter, at such low potentials (or low electrode Ca2+), CaCC achieve only threshold activation, so that the effects of residual contaminating currents that escape Cs+, TEACl, and glibenclamide inhibition on τ calculations might be significant. In contrast, when test potentials exceed 20 mV and currents are large, voltage dependence is absent. A thorough study of this issue would require molecular identification of the channel and accessory proteins, heterologous expression to a high level, and reexamination of voltage and Ca2+ dependence when CaCC dominates over a large range of voltage. In contrast to findings related to activation kinetics, deactivation of CaCC in DVR pericytes parallels that of many other cells (13, 31, 32). It follows an exponential decay, the rate of which is dependent on voltage when [Ca]CYT is high.

Key information concerning plausible structure and regulation of CaCC has recently emerged. The elusive pursuit of their molecular identity yielded to a triad of reports in which CaCC characteristics were reproduced by expression of TMEM16A, a 1,008-amino acid protein, in heterologous systems (5, 41, 48). TMEM16A has been renamed anoctamin 1, and prior candidates for CaCC identity have fallen into disfavor. These include the classical ClCa, which may be an adhesion molecule, and the bestrophins, which may serve to modulate Ca2+ sensing within the endoplasmic reticulum (16, 17, 20, 26). Anoctamins do not share homology with other ion channel classes. Of 10 isoforms, Ano1 and Ano2 appear to predominate as cell surface proteins. Their predicted structure includes eight membrane-spanning domains with a putative pore between transmembrane regions 5 and 6. Interestingly, the structure lacks an obvious Ca2+-binding motif. Nonetheless, excision of patches into high-Ca2+ extracellular buffer can increase Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance in several preparations (24, 27), including our own (54). Thus it seems likely that Ca2+ can directly activate some CaCC via binding to the channel or accessory, membrane-bound protein. The identity of CaCC in the DVR pericyte has yet to be fully established.

Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance has been observed by other investigators. A probable role for a CaM-binding (e.g., anoctamins lack an IQ-binding motif) or a CaM-regulated accessory protein is supported by the observation that W-7 was both highly and reversibly effective; it inhibited DVR Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel whole cell currents during repetitive depolarizations. Roles for CaMKII regulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance have been found in various tissues. Wang and Kotlikoff (46) observed that caffeine-stimulated Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in tracheal smooth muscle spontaneously deactivate, independent of temporal changes in [Ca]CYT. CaMKII inhibition prevented Ca2+- and voltage-independent deactivation. They concluded that CaMKII inhibits CaCC. A similar conclusion was reached by Greenwood and colleagues (18) in their work with myocytes from pulmonary artery. In contrast to CaMKII-induced inhibition, activation of CaCC has often been found to be dependent on CaM kinase activity. Such activation been observed in diverse preparations such as T84 colonic secretory cells, airway epithelia, lymphocytes, macrophages, endothelia, and pancreatic epithelia (7, 19, 21, 32, 33, 45, 47). Given that CaMKII is a CaM-dependent kinase, there is some contrast between the effects of the putative CaM inhibitor W-7, which was highly effective to block currents, and the CaMKII blocker KN-93, which required application by cytoplasm and bath from break-in to achieve inhibition. The reason for this is uncertain. It might relate to membrane permeation or the relative effectiveness of the agents to block their targets or point to additional non-CaMKII activation mechanisms that are CaM-dependent but unaffected by KN-93. Given the lack of specificity of kinase inhibitors (8, 11), a firm conclusion concerning the origin of that disparity cannot be provided.

MLCK is recognized to have additional roles, apart from its ability to mediate smooth muscle contraction. Modulation of channel activity by MLCK, including CaCC activity, has been described (42, 43, 51, 52). Hence, we tested for analogous DVR pericyte CaCC regulation. The results showed that putative MLCK inhibitors potently reduce DVR pericyte CaCC activity; ML-7 and ML-9 were highly effective. Given that MLCK is known to be very selective for phosphorylation of myosin light chain (23), that result must be interpreted with caution. Direct phosphorylation of the Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel protein by MLCK may not be the explanation. ML-7 and ML-9 lack specificity (8, 11), and actions involving non-kinase-dependent regulation of the cytoskeleton have been described (6). ANG II-induced depolarization was promptly reversed by ML-7. This is consistent with inhibition of Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance by ML-7; however, we also recognize that activation of one or more classes of K+ channels could explain the results.

Perspectives and Significance

In summary, we examined the Ca2+- and voltage-dependent regulation of murine DVR pericyte CaCC. Its activity is highly sensitive to membrane potential, [Ca]CYT, and kinase inhibition by W-7, ML-7, ML-9, and KN-93. The specificity of kinase blockers can be brought into question, and these experiments were performed in vitro by patch-clamp methods that dialyze the cytoplasm and expose the cells to high oxygen tensions and low temperatures. Nonetheless, support for plausible combinations of kinase-, voltage-, and Ca2+-dependent regulation of DVR pericyte CaCC, membrane potential, and contraction seems strong. We conclude that pharmacological manipulation of phosphorylation state might provide a target for preservation of medullary blood flow to protect against ischemic insults.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant 09SDG2130035 (to C. Cao) and National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HL-78870, R37 DK-42495, and R01 DK-67621 (to T. L. Pallone).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Activation of calcium-dependent chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J Gen Physiol 108: 35–47, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Differences in regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in colonic and parotid secretory cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C161–C166, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao C, Goo JH, Lee-Kwon W, Pallone TL. Vasa recta pericytes express a strong inward rectifier K+ conductance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1601–R1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao C, Lee-Kwon W, Silldorff EP, Pallone TL. KATP channel conductance of descending vasa recta pericytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1235–F1245, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322: 590–594, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carton I, Trouet D, Hermans D, Barth H, Aktories K, Droogmans G, Jorgensen NK, Hoffmann EK, Nilius B, Eggermont J. RhoA exerts a permissive effect on volume-regulated anion channels in vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C115–C125, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao AC, Kouyama K, Heist EK, Dong YJ, Gardner P. Calcium- and CaMKII-dependent chloride secretion induced by the microsomal Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor 2,5-di-(tert-butyl)-1,4-hydroquinone in cystic fibrosis pancreatic epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 96: 1794–1801, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P. Guidelines for the effective use of chemical inhibitors of protein function to understand their roles in cell regulation. Biochem J 425: 53–54, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowley AW., Jr Role of the renal medulla in volume and arterial pressure regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1–R15, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowley AW., Jr Renal medullary oxidative stress, pressure-natriuresis, and hypertension. Hypertension 52: 777–786, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J 351: 95–105, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards A, Pallone TL. Mechanisms underlying angiotensin II-induced calcium oscillations. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F568–F584, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans MG, Marty A. Calcium-dependent chloride currents in isolated cells from rat lacrimal glands. J Physiol 378: 437–460, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans RG, Fitzgerald SM. Nitric oxide and superoxide in the renal medulla: a delicate balancing act. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 9–15, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RG, Majid DS, Eppel GA. Mechanisms mediating pressure natriuresis: what we know and what we need to find out. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32: 400–409, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flores CA, Cid LP, Sepulveda FV, Niemeyer MI. TMEM16 proteins: the long awaited calcium-activated chloride channels? Braz J Med Biol Res 42: 993–1001, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galietta LJ. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels? Biophys J 97: 3047–3053, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol 534: 395–408, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 719–758, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Physiol 587: 2127–2139, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holevinsky KO, Jow F, Nelson DJ. Elevation in intracellular calcium activates both chloride and proton currents in human macrophages. J Membr Biol 140: 13–30, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J Gen Physiol 92: 145–159, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamm KE, Stull JT. Dedicated myosin light chain kinases with diverse cellular functions. J Biol Chem 276: 4527–4530, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koumi S, Sato R, Aramaki T. Characterization of the calcium-activated chloride channel in isolated guinea-pig hepatocytes. J Gen Physiol 104: 357–373, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriz W. Structural organization of the renal medulla: comparative and functional aspects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 241: R3–R16, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunzelmann K, Kongsuphol P, Aldehni F, Tian Y, Ousingsawat J, Warth R, Schreiber R. Bestrophin and TMEM16—Ca2+ activated Cl− channels with different functions. Cell Calcium 46: 233–241, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuruma A, Hartzell HC. Bimodal control of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel by different Ca2+ signals. J Gen Physiol 115: 59–80, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemley KV, Kriz W. Cycles and separations: the histotopography of the urinary concentrating process. Kidney Int 31: 538–548, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGill JM, Yen MS, Basavappa S, Mangel AW, Kwiatkowski AP. ATP-activated chloride permeability in biliary epithelial cells is regulated by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 208: 457–462, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol 207: 123–131, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilius B, Droogmans G. Amazing chloride channels: an overview. Acta Physiol Scand 177: 119–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilius B, Prenen J, Voets T, Van den BK, Eggermont J, Droogmans G. Kinetic and pharmacological properties of the calcium-activated chloride-current in macrovascular endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 22: 53–63, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimoto I, Wagner JA, Schulman H, Gardner P. Regulation of Cl− channels by multifunctional CaM kinase. Neuron 6: 547–555, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallone TL, Cao C, Zhang Z. Inhibition of K+ conductance in descending vasa recta pericytes by ANG II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1213–F1222, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pallone TL, Huang JM. Control of descending vasa recta pericyte membrane potential by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F1064–F1074, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pallone TL, Silldorff EP, Cheung JY. Response of isolated rat descending vasa recta to bradykinin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H752–H759, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pallone TL, Turner MR, Edwards A, Jamison RL. Countercurrent exchange in the renal medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R1153–R1175, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pallone TL, Zhang Z, Rhinehart K. Physiology of the renal medullary microcirculation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F253–F266, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park F, Mattson DL, Roberts LA, Cowley AW., Jr Evidence for the presence of smooth muscle α-actin within pericytes of the renal medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1742–R1748, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhinehart K, Zhang Z, Pallone TL. Ca2+ signaling and membrane potential in descending vasa recta pericytes and endothelia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F852–F860, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 134: 1019–1029, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen MR, Furla P, Chou CY, Ellory JC. Myosin light chain kinase modulates hypotonicity-induced Ca2+ entry and Cl− channel activity in human cervical cancer cells. Pflügers Arch 444: 276–285, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tran QK, Watanabe H, Zhang XX, Takahashi R, Ohno R. Involvement of myosin light-chain kinase in chloride-sensitive Ca2+ influx in porcine aortic endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 44: 623–631, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsien R, Pozzan T. Measurement of cytosolic free Ca2+ with quin2. Methods Enzymol 172: 230–262, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner JA, Cozens AL, Schulman H, Gruenert DC, Stryer L, Gardner P. Activation of chloride channels in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells by multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Nature 349: 793–796, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. Inactivation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14918–14923, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Worrell RT, Frizzell RA. CaMKII mediates stimulation of chloride conductance by calcium in T84 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 260: C877–C882, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455: 1210–1215, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, Cao C, Mangano M, Zhang Z, Silldorff EP, Lee-Kwon W, Payne K, Pallone TL. Descending vasa recta endothelium is an electrical syncytium. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1688–R1699, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Cao C, Zhang Z, Wier WG, Edwards A, Pallone TL. Membrane current oscillations in descending vasa recta pericytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F656–F666, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Paterson WG. Role of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels and MLCK in slow IJP in opossum esophageal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G104–G114, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Paterson WG. Role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in control of membrane potential and nitrergic response in opossum lower esophageal sphincter. Br J Pharmacol 140: 1097–1107, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z, Cao C, Lee-Kwon W, Pallone TL. Descending vasa recta pericytes express voltage operated Na+ conductance in the rat. J Physiol 567: 445–457, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z, Huang JM, Turner MR, Rhinehart KL, Pallone TL. Role of chloride in constriction of descending vasa recta by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R1878–R1886, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Z, Rhinehart K, Pallone TL. Membrane potential controls calcium entry into descending vasa recta pericytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R949–R957, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]