Abstract

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central controller of cell growth, proliferation, metabolism and angiogenesis. mTOR signaling is often dysregulated in various human diseases and thus attracts great interest in developing drugs that target mTOR. Currently it is known that mTOR functions as two complexes, mTOR complex 1/2 (mTORC1/2). Rapamycin and its analogs (all termed rapalogs) first form a complex with the intracellular receptor FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) and then bind a domain separated from the catalytic site of mTOR, blocking mTOR function. Rapalogs are selective for mTORC1 and effective as anticancer agents in various preclinical models. In clinical trials, rapalogs have demonstrated efficacy against certain types of cancer. Recently, a new generation of mTOR inhibitors, which compete with ATP in the catalytic site of mTOR and inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 with a high degree of selectivity, have been developed. Besides, some natural products, such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), caffeine, curcumin and resveratrol, have been found to inhibit mTOR as well. Here, we summarize the current findings regarding mTOR signaling pathway and review the updated data about mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents.

Keywords: mTOR, mTORC1, mTORC2, inhibitor, rapamycin, rapalogs, cancer

1. Introduction

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), an atypical serine/threonine (S/T) protein kinase, is a central controller of cell growth, proliferation and metabolism [1,2]. Cumulative evidence indicates that mTOR acts as a ‘master switch’ of cellular anabolic and catabolic processes, regulating the rate of cell growth and proliferation by virtue of its ability to sense mitogen, energy and nutrient levels [3,4]. Dysregulation of mTOR and other proteins in the signaling pathway often occurs in a variety of human malignant diseases and the tumor cells have shown higher susceptibility to mTOR inhibitors than normal cells. For example, activation of the mTOR pathway was noted in squamous cancers [5], adenocarcinomas [6], bronchioloalveolar carcinomas [7], colorectal cancers [8], astrocytomas [9] and glioblastomas [10]. A recent immunohistochemical study performed in tissue arrays containing 124 tumors from 8 common human tumor types revealed that approximately 26% of tumors (32/124) are predicted to be sensitive to mTOR inhibition [11]. These findings indicate a potential role of dysregulated mTOR signaling in tumorigenesis and support the currently ongoing clinical development of mTOR inhibitors as a potential tumor-selective therapeutic strategy.

mTOR complex 1/2 (mTORC1/2) are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammals [12,13]. These two complexes consist of unique mTOR-interacting proteins that determine their substrate specificity. Rapamycin, the first defined mTOR inhibitor, specifically inhibits mTOR, resulting in inhibition of cell growth, cell cycle progression and cell proliferation [13]. However, the poor aqueous solubility and chemical stability of rapamycin restricts its application for cancer therapy. Therefore, several rapamycin analogs with more favorable pharmaceutical characteristics have been developed, including CCI-779 (Temsirolimus, Wyeth, Madison, NJ, USA), RAD001 (Everolimus, Novartis, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), AP23573 (Deforolimus, ARIAD, Cambridge, MA, USA), 32-deoxorapamycin (SAR943) or zotarolimus (ABT-578, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) for malignancies [14], chronic allergic inflammation [15] or cardiovascular stent implantation [16]. Preclinical studies have shown their antiproliferative activity against a diverse range of cancer types, and clinical trials have demonstrated promising anticancer efficacy in certain types of cancer [14,17,18]. A new generation of mTOR inhibitors, which was designed to target ATP binding site of mTOR and inhibit the kinase-dependent functions of both TORC1 and TORC2, have been developed. These molecules, including PP242, PP30, Torin1, Ku-0063794, WAY-600, WYE-687 and WYE-354, exhibit potent and selective inhibition of mTOR. In addition, some naturally occurring compounds, such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and curcumin, have been found to downregulate mTOR signaling. Because of space limitation, we apologize for not being able to cite all related published studies.

2. mTOR complexes

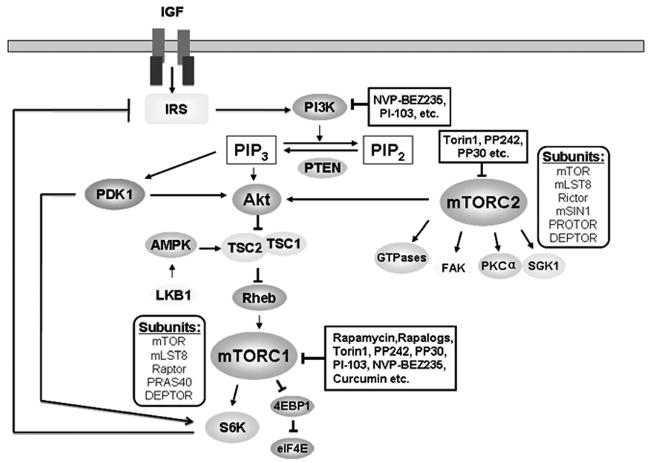

mTOR, also known as FRAP (FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein), RAFT1 (rapamycin and FKBP12 target), RAPT 1 (rapamycin target 1), or SEP (sirolimus effector protein), is a 289 kDa atypical S/T kinase [19-22]. mTOR is considered a member of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-kinase-related kinase (PIKK) superfamily since the C-terminus of mTOR shares strong homology to the catalytic domain of PI3K [23,24]. In mammalian cells, mTOR functions as two distinct signaling complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2. Besides the mTOR catalytic subunit, mTORC1 consists of Raptor (regulatory associated protein of mTOR), mLST8 (also termed G-protein β-subunit-like protein, GβL, a yeast homolog of LST8), and PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa) (Fig. 1) [25-27]. mTORC1 is rapamycin-sensitive and plays a critical role in the regulation of cell growth, proliferation, survival and motility by phosphorylation of the two best-characterized downstream effector molecules, S6K1 and 4E-BP1, which promote mRNA translation and ribosome biogenesis [25,26,28].

Fig. (1).

IGF-I-mediated mTOR signaling network. mTORC1 consists of mTOR, Raptor, mLST8, PRAS40 and DEPTOR. TSC1/2-Rheb is the major upstream regulator of mTORC1. S6K1 and 4E-BP1 are two best-characterized downstream effector molecules of mTORC1. Activated S6K1 phosphorylates IRS1 and promotes its degradation, and thus attenuates PI3K/Akt signaling. The mTORC2 subunits include mTOR, Rictor, mSin1, mLST8, PROTOR and DEPTOR. The upstream regulation of mTORC2 remains unknown. Arrows represent activation, whereas bars represent inhibition. IRS, insulin receptor substrates; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol (4, 5)-bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-trisphosphate; PDK1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; Rheb, Ras homolog enriched in brain; AMPK, AMP-activated kinase.

Rapamycin, a potent and specific mTORC1 inhibitor, has been an invaluable research tool throughout the study of mTORC1 in cell biology. Thus, the upstream regulators and downstream effectors of this rapamycin-sensitive mTOR complex, mTORC1, are better known than that of mTORC2 complex. The mTORC1 signaling can be activated by upstream signals, including hormones, nutrients and growth factors, such as insulin and type I insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) [29]. As shown in Fig. 1, in response to ligand binding, the IGF-I receptor (IGF-IR), a transmembrane tyrosine kinase, is activated via auto-phosphorylation of multiple tyrosine residues. Activated IGF-IR in turn phosphorylates the insulin receptor substrates 1-4 (IRS1-4) and src- and collagen-homology (SHC) adaptor proteins [30]. Phosphorylated IRS recruits the p85 subunit of PI3K and signals to the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K, resulting in activation of PI3K. Activated PI3K catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (4, 5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-trisphosphate (PIP3). This pathway is negatively regulated by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome ten), a dual-specificity protein and lipid phosphatase. Increased PIP3 binds to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of Akt and, in combination with additional S/T phosphorylation of Akt by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and mTORC2, results in full activation of Akt. Subsequently, activated PI3K or Akt may positively regulate mTOR, leading to increased phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 [1]. Activated S6K1 promotes translation initiation through phosphorylation of the 40s ribosomal subunit, which has been suggested to increase the translational efficiency of a class of mRNA transcripts with a 5′-terminal oligopolypyrimidine (5′-TOP) [31,32]. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by mTOR also stimulates translation initiation through the release of eIF4E from 4E-BP1, allowing eIF4E to associate with eIF4G and other relevant factors to enhance cap-dependent translation [33,34]. Studies have placed tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), a heterodimer that comprises TSC1 and TSC2 subunits, as a modulator between PI3K/Akt and mTOR [35-37]. The TSC1/2 complex acts as a repressor of mTOR function [35-37]. TSC2 has GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity towards the Ras family small GTPase Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in brain), and TSC1/2 antagonizes the mTOR signaling pathway via stimulation of GTP hydrolysis of Rheb [36-41]. The TSC can also be activated by energy depletion through the activation of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK). In times of any stress that depletes cellular ATP, such as oxidative stress, hypoxia, or nutrient deprivation, activated AMPK phosphorylates unique sites on TSC2, activating the Rheb-GAP activity of TSC, which catalyzes the conversion of Rheb-GTP to Rheb-GDP and thus inhibits mTORC1 activity (Fig. 1) [36-41].

Like mTORC1, mTORC2 also include mTOR and mLST8, but instead of raptor, mTORC2 contains two unique subunits, rictor (rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR) and mSin1 (mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1) (Fig. 1) [42-44]. mTORC2 was originally thought to be rapamycin-insensitive. However, recent study showed that in some cell lines, prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits the assembly and function of mTORC2 [45]. The main function of mTORC2 is to regulate the actin cytoskeleton [42,46,47]. Recently, the important finding that mTORC2 directly phosphorylates Akt on the hydrophobic motif site S473 adds a new insight into the role of mTOR in cancer [48]. mTORC2 may modulate cell survival in response to growth factors by phosphorylating on S473 of Akt, which is one of the most important survival kinases [42,48,49]. Active Akt regulates different cellular processes including cell growth, proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis and glucose metabolism [50]. Considering the importance of Akt signaling and the critical role of mTORC2 in Akt activation, mTORC2 will attract great attention as a novel drug target, especially for treating cancers characterized by hyperactive Akt.

Since growth factors stimulate mTORC2 activity and low concentrations of wortmannin, a specific PI3K inhibitor, inhibits Akt S473 phosphorylation, suggesting that mTORC2 activation lies downstream of PI3K signaling [48,51]. However, the mechanism by which mTORC2 is activated is not entirely clear. Akt is the best-characterized substrate of mTORC2. Several knockdown and knockout studies demonstrated that mTORC2 regulates PKCα phosphorylation as well [43,52]. The phosphorylation of PKCα on S657 is dramatically reduced in rictor-null MEFs [53]. In Drosophila, reduction in rictor by dsRNAs also decreases the phosphorylation of dPKCα [43]. In addition, it was reported that mTORC2 may function as upstream of Rho GTPases to regulate the actin cytoskeleton [42]. In mTOR, mLST8 or rictor siRNA-transfected cells, expression of constitutively active form of Rac1 (Rac1-L61) or RhoA (RhoA-L63) restored organization of the actin cytoskeleton, indicating that mTORC2 may regulate the actin cytoskeleton through RhoA and Rac1 [42]. Most recently, the serum glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1) was identified as a new substrate of mTORC2 [54-56]. In rictor, mSin1 or mLST8 knockout fibroblasts, both the activity and hydrophobic motif phosphorylation of SGK1 (S422) are abolished [54]. Moreover, S422 can also be phosphorylated by immunoprecipitated mTORC2 in vitro, further confirming that mTORC2 regulates SGK1 [54].

3. mTOR inhibitors

3.1. Rapamycin and its analogs

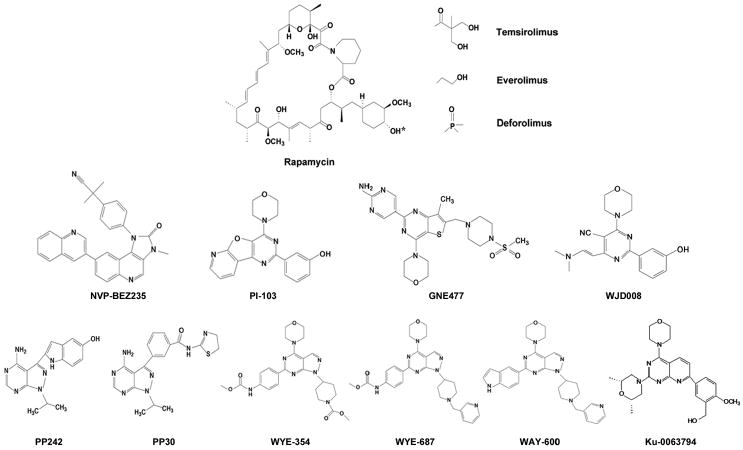

Rapamycin is the first mTOR inhibitor discovered and its chemical structure is shown in Fig. 2. It is a macrocyclic lactone produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus and was first found from a soil sample of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) during a discovery program for anti-microbial agents in 1975 [57,58]. Rapamycin was initially developed as an anti-fungal agent and subsequently discovered to have equally potent immunosuppressive properties [57,59-61]. The preclinical studies on the immunosuppressive effect of rapamycin has been extensively reviewed [62]. In 1999, rapamycin (Rapamune, Sirolimus) was approved as an immunosuppresive drug by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA [63]. Extensive studies revealed the action mechanism of rapamycin: upon entering the cells, rapamycin binds the intracellular receptor FKBP12, forming an inhibitory complex, and together they bind a region in the C terminus of TOR proteins termed FRB (FKB12-rapamycin binding) domain, thereby exerting its cell growth-inhibitory and cytotoxic effects by inhibiting the functions of TOR signaling to downstream targets [12,64-66]. The actual mechanism by which rapamycin inhibits mTOR signaling remains to be defined. It has been proposed that rapamycin-FKBP12 may inhibit mTOR function by inhibiting the interaction of raptor with mTOR and thereby disrupting the coupling of mTORC1 with its substrates [67]. Recently it has also been described that phosphatidic acid (PA), the metabolite of phospholipase D (PLD), is required for the stabilization of mTORC1 and mTORC2, which may explain the differential sensitivities to rapamycin and further reveal the mechanism by which rapamycin inhibits mTOR [68]. In the renal cancer cell line 786-O, the IC50 of rapamycin to inhibit S6K T389 phosphorylation by mTORC1 was ∼20 nM, and to suppress Akt S473 phosphorylation by mTORC2 was 20 μM, indicating that varied concentrations of rapamycin are needed to inhibit mTORC1 and mTORC2 [68]. PA was found to be required for the association of mTOR with raptor and rictor, thereby stabilizing mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively. As PA interacts more strongly with mTORC2 than with mTORC1, much higher concentrations of rapamycin are needed to disrupt the association of PA with mTORC2 than with mTORC1 [69].

Fig. (2).

Chemical structures of rapalogs, mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors, and mTORC1/2 inhibitors. Temsirolimus, everolimus and deforolimus have the indicated O-substitutions at the C-40 hydroxyl (marked with *) of rapamycin.

The anti-proliferative effect of rapamycin has been investigated in numerous murine and human cancer cell lines. Rapamycin potently inhibits cell proliferation in cell lines derived from rhabdomyosarcoma [70,71], neuroblastoma, glioblastoma [72], small cell lung cancer [73], osteoscarcoma [74], pancreatic cancer [75], breast cancer, prostate cancer [76,77], murine melanoma and B-cell lymphoma [78,79]. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin also suppresses hypoxia-mediated angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation in vitro [80]. In in vivo mouse models, rapamycin displays strong inhibitory effects on tumor growth and angiogenesis, which are related to a reduced production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [81]. Furthermore, rapamycin induces apoptosis in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma independent of p53, but specifically through inhibition of mTOR signaling [71].

The clinical development of rapamycin as an anticancer agent was precluded because of its poor water solubility and chemical stability. Therefore, several rapalogs with improved pharmacokinetic (PK) properties and reduced immunosuppressive effects are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for cancer treatments [14,82]. The chemical structures of these rapalogs, including temsirolimus (CCI-779), everolimus (RAD001), and deforolimus (AP23573), are shown in Fig. 2. In addition, other rapalogs, such as 32 deoxy-rapamycin (SAR943) or zotarolimus (ABT-578), have been developed to prevent chronic allergic inflammation [15] or for cardiovascular stent implantation [16]. Rapalogs share the same action mechanism as rapamycin. They first form a complex with FKBP12, and then bind the FRB domain of mTOR to inhibit mTOR function (Table 1) [82].

Table 1. mTOR inhibitors.

| mTOR inhibitors | Structure | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapalogs | |||

| Rapamycin | Macrolide ester | Functions by binding to the immunophilin FKBP12 | Reviewed in [82] |

| Temsirolimus (CCI-779) | Partial mTORC1 inhibitor | ||

| Everolimus (RAD001) | Cell-type specific mTORC2 inhibitor | ||

| Deforolimus (AP23573) | |||

| 32 deoxy-rapamycin (SAR943) | |||

| Zotarolimus (ABT-578) | |||

| mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors | |||

| GNE477 | Thienopyrimidine | mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitor | [120] |

| NVP-BEZ235 | Imidazoquinazoline | mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitor | [121] |

| PI-103 | Tricyclic pyridofuropyrimidine | mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitor | [122] |

| XL765 | Not available | mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitor | [123] |

| WJD008 | 5-cyano-6-morpholino-4-substituted-pyrimidine analogue | mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitor | [124] |

| mTORC1/2 inhibitors | |||

| PP242 | Pyrazolopyrimidines | mTOR kinase inhibitor | [136] |

| PP30 | Pyrazolopyrimidines | mTOR kinase inhibitor | [136] |

| Torin1 | Pyridinonequinoline | mTOR kinase inhibitor | [137] |

| WYE-354 | Pyrazolopyrimidine | ATP competitive inhibitor of mTOR | [138] |

| WAY-600 | Pyrazolopyrimidine | ATP competitive inhibitor of mTOR | [138] |

| WYE-687 | Pyrazolopyrimidine | ATP competitive inhibitor of mTOR | [138] |

| Ku-0063794 | pyridopyrimidin | Specific mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitor | [139] |

| Diet-derived natural products | |||

| Curcumin | Diferuloylmethane | Disrupts the mTOR-Raptor Complex | [140] |

| Resveratrol | Trans-3,4′, 5-trihydroxystilbene | Inhibits PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | [141,142] |

| epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | Polyphenol | Inhibits PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | [143] |

| Genistein | Isoflavone | Inhibits PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | [144,145] |

| 3,3-Diindolylmethane (DIM) | Indole-3-carbinol | Inhibits both mTOR and Akt activity | [146] |

| Caffeine | methylxanthine | Inhibits TORC1 | [147] |

Temsirolimus (Fig. 2), which is a dihydroxymethyl propionic acid ester of rapamycin, was designed to increase the solubility of rapamycin and thus it can be administered both orally and intravenously [83]. Temsirolimus was identified in the 1990s and subsequently developed as an agent for the treatment of patients with cancer. Temsirolimus suppresses mTOR activity and inhibits the mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, decreasing expression of several key proteins involved in the regulation of cell cycle [17,84]. In preclinical studies, temsirolimus showed potent growth inhibitory effect in the six of eight cancer cell lines with IC50 in the low nanomolar range [85]. It was found that the sensitive cell lines were estrogen receptor α positive, and/or Her2/Neu oncogene overexpressed, or loss of the tumor suppressor gene product PTEN, whereas the two resistant cell lines had none of these features [85]. In a variety of animal models of tumors such as gliomas, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and pancreatic cancer, temsirolimus alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs also demonstrated significant antitumor activity [72,86,87]. In two single agent Phase I clinical trials in patients with solid tumors, temsirolimus was administered intravenously at doses ranging from 7.5 to 220 mg/m2 by two different delivery schedules - weekly versus daily for 5 days every 2-3 weeks [88]. Although the dose-limiting toxicities such as mucositis, depression, thrombocytopaenia and hyperlipaemia were observed, temsirolimus was generally tolerated [89]. Over the entire range of doses, tumor responses were observed in patients with renal, breast and non-small cell lung cancer [88,90,91]. Based on these results, the phase II clinical trails were conducted in patients with various types of tumors, including renal cell carcinoma [90], glioblastoma multiforme [92,93], mantle cell lymphoma [94], melanoma [95], neuroendocrine tumors [96], breast cancer [97], and lung cancer [98] by using three different doses (25, 75, and/or 250 mg i.v.) of temsirolimus given weekly. Little efficacy of single-agent temsirolimus was observed in patients with neuroendocrine tumors, recurrent glioblastoma multiforme, melanoma and lung cancer [89,92]. However, in the trials of pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, mantle cell lymphoma and locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, temsirolimus showed antitumor activity [89,94,97]. At higher dose levels, the greater toxicity was reported, but the drug had general tolerability over a wide range of doses. As temsirolimus (25 mg or 250 mg weekly) resulted in similar efficacy, the 25 mg dose level was suggested to be pursued for further investigations. Recently, in a large multicenter randomized phase III trial in patients with advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma, the efficacy was compared by giving temsirolimus alone, interferon-α alone or with temsirolimus weekly intravenous administration [99]. Compared with those receiving interferon-α, the patients treated with temsirolimus had a significantly longer median survival (10.9 versus 7.3 months) [99]. The combination of temsirolimus and interferon-α did not improve survival in those patients [99]. In order to investigate a dose response relationship, two temsirolimus regimens were chosen in the most recent phase III study of temsirolimus in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. Each temsirolimus regimen initially used 175 mg per week for 3 weeks followed by weekly doses of either 25 mg or 75 mg [100]. Compared with the investigator's choice therapy, the 75 mg per week regimen significantly improved the objective response rate and progression-free survival, while the 25 mg per week regimen did not [100]. Thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia and asthenia were the most frequent temsirolimus-related, grade 3 or 4 adverse events [100].

Everolimus (Fig. 2), which has an O-(2-hydroxyethyl) chain substitution at position C-40 on the rapamycin structure, is an orally available rapamycin analog. Everolimus was formulated in an attempt to increase the oral bioavailability of rapamycin. Compared with rapamycin, everolimus was found to have better pharmacokinetic characteristics including a shorter half-life (28 h instead of 60 h), a slightly higher bioavailability, and a higher correlation of bioavailability with the administered dosage [101,102]. Preclinical studies showed that everolimus inhibited growth factor-driven cell proliferation of a lymphoid cell line and vascular smooth muscle cells [103]. The immunosuppressive effect of everolimus was demonstrated by its inhibition of mouse and human mixed lymphocyte reaction and antigen-driven proliferation of human T-cell clones [103]. In an autoimmune disease model and several allotransplantation models, everolimus was shown to have at least equal efficacy to rapamycin when administered orally [103]. In the syngeneic CA20948 rat pancreatic tumor model, everolimus displayed potent antitumor effect, and this effect was suggested to be associated with the significant suppression of S6K1 and the regulation of 4E-BP1 activity [104]. As a result of these activities, everolimus has been clinically developed both as an immunosuppressive agent in organ transplantation and as a novel therapy in the treatment of human cancer [105,106]. A phase I study investigating the safety, tolerability, PK and pharmacodynamic (PD) of everolimus in patients with advanced tumor indicated that everolimus was satisfactorily tolerated at dosages up to 70 mg/week and 10 mg/day with predictable PK [107]. Another study using preclinical and clinical PK/PD modeling predicted that daily dosing (at 5 and 10 mg) has a more profound effect on target inhibition than the same dose on a weekly schedule [108]. A tumor PD phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumors also confirmed that daily everolimus dosing with 10 mg achieved more profound inhibition of mTOR pathway [109]. In subsequent phase II study performed in 41 patients with confirmed predominantly clear cell renal cell cancer (of whom 83% had received prior therapy), 10 mg/day oral everolimus showed encouraging antitumor activity against metastatic renal cell cancer as indicated by a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 11.2 months, a median overall survival of 22.1 months, partial responses rate of 14%, and a PSF ≥ 6 months for approximately 70% of patients [110]. The encouraging phase II results of everolimus led to the start of a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma that had progressed on VEGF-targeted therapy. The results showed that 10 mg once daily treatment with everolimus prolonged PFS relative to placebo group [111]. Stomatitis (40%), rash (25%) and fatigue (20%) were the most common reported adverse events, but most adverse events were mild [111]. In addition, approximately 8% of patients receiving everolimus developed pneumonitis, whereas only 3% of patients had pneumonitis of grade 3 severity [111]. Noninfectious pneumonitis was reported to be a toxicity of rapamycin derivatives, including everolimus [112]. Therefore, patients receiving mTOR inhibitors should be monitored and those with moderate or severe symptoms should be managed with dose reduced or stopped until symptoms improve or discontinuation [113]. Based on the trial data and uniform National Comprehensive Cancer Network consensus, everolimus received a category I recommendation for the second-line treatment of patients with advanced renal cell cancer after failure treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib or sorafenib.

Deforolimus (Fig. 2), a phosphorous-containing analog of rapamycin, was designed based on computational modeling studies. Compared to rapamycin, deforolimus has more favorable pharmaceutical and pharmacological properties, including aqueous solubility, chemical stability and bioavailability [114]. Deforolimus alone or in combination with several chemotherapeutic agents has shown potent inhibitory effects on the proliferation of diverse tumor cell lines in vitro and induces partial tumor regressions in mice bearing xenografts [115]. In clinical studies, i.v. and oral formulations of deforolimus are currently being tested. Phase I trials with both formulations (i.v. and oral) showed that deforolimus was well tolerated, and exhibited antitumor activity in several tumor types at all doses tested [114]. For the i.v. formulation, two schedules of administration were explored: once daily for 5 days every 2 weeks, and once weekly [114,116]. Common side effects with the administration of deforolimus included mouth sores, rash, mucositis, fatigue, and anorexia. Mucositis was the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) in both schedules [114,116]. Based on the safety and PK profiles, 12.5 mg once daily for 5 days every 2 weeks was chosen as the recommended phase II dose [14]. In PD analyses, deforolimus at dose levels associated with minimal toxicity was shown to inhibit mTOR as indicated by reduced phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 [14]. Recently, the results of the study on the oral formulation of deforolimus in patients with advanced/metastatic solid tumors refractory to therapy were presented [117]. It appeared that oral deforolimus had a safety and anti-tumor activity profile consistent with the intravenous form. The DLT for all regimens was aphthous-ulcer like mouth sores that were reversible by dose reduction or symptomatic therapy in subsequent cycles [117]. The pharmacokinetic study on oral deforolimus revealed that following oral administration, the maximum concentration (Cmax) occurred at 2-3 hours and the median terminal half life is 35-70 hours [118]. It was suggested that 40 mg five times daily each week is an active, well-tolerated regimen and this oral dose has been selected for further evaluation in a global phase 3 trial [117]. Most recently, a phase I study was performed to evaluate the deforolimus administered i.v. combined with paclitaxel [119]. Two dose combinations: 12.5 mg deforolimus with 80 mg paclitaxel and 37.5 mg deforolimus with 60 mg paclitaxel, appear to be well tolerated and are recommended for Phase II studies [119]. PK studies suggested absence of drug-drug interaction. PD data in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells showed decreased phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 [119]. This combination demonstrated potential anti-angiogenic effects and encouraging antitumor activity, therefore justifying further development.

3.2. mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors

A class of small molecules related to mTOR kinase inhibition, such as GNE477, NVP-BEZ235, PI-103, XL765 and WJD008, is the mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors (Table 1). Their chemical structures are shown in Fig. 2. These molecules simultaneously target the ATP binding sites of mTOR and PI3K with similar potency and cannot be used to selectively inhibit mTOR-specific activities [120-124]. Therefore, they are generally not useful as research tools to study the regulation or function of mTOR. However, they may have unique advantages over single-target inhibitors in certain disease settings because they can target at least three key enzymes (PI3K, Akt, and mTOR) in the PI3K signaling pathway. Inhibition of mTORC1 activity alone by rapalogs may result in the enhanced activation of the PI3K axis because of the mTOR-S6K-IRS1 negative feedback loop [125]. Therefore, the mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors might be sufficient to avoid PI3K pathway reactivation.

NVP-BEZ235 (Fig. 2), a novel, dual class I PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, is an imidazo quinoline derivative that is undergoing phase I/II clinical trials. NVP-BEZ235 binds the ATP-binding clefts of PI3K and mTOR kinase, thereby inhibiting their activities [121]. Increasing evidence showed that NVP-BEZ235 is able to effectively and specifically reverse the hyperactivation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway, resulting in potent antiproliferative and antitumor activities in a broad range of cancer cell lines and experimental tumor models [126-128]. In breast cancer cells, NVP-BEZ235 blocked the activation of the downstream effectors of mTORC1/2, including Akt, S6, and 4E-BP1 [126]. Especially, at doses higher than 500 nM, NVP-BEZ235 completely suppressed Akt phosphorylation, irrespective of exposure duration. Meanwhile, NVP-BEZ235 showed greater antiproliferative activity than the allosteric selective mTOR inhibitor everolimus in all cancer cell lines tested [126]. In a xenograft model of BT474-derived breast cancer cells overexpressing either the p110-α H1047R oncogenic mutation or the empty vector, NVP-BEZ235 significantly inhibited tumor growth of both xenografts [126]. Consistently, NVP-BEZ235 at nanomolar concentrations suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, S6K and 4E-BP1, and inhibited growth of a panel of cancer cells, including those derived from myeloma [128,129], glioma [130], osteosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, as well as rhabdomyosarcoma [131]. In sarcoma cells, NVP-BEZ235 blocked cell proliferation, and inhibited cell migration and cancer metastasis [131]. In combination with melphalan, doxorubicin and bortezomib, NVP-BEZ235 showed synergistic or additive effects on cell growth inhibition in multiple myeloma cells [128]. In a xenograft model from TC-71 Ewing's sarcoma cell line, combined treatment with NVP-BEZ235 and vincristine effectively inhibited tumor growth and metastasis [131]. These data suggest potential clinical activity of the combined use of NVP-BEZ235 with chemotherapeutic agents.

PI-103 (Fig. 2), another dual class I PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, is a small synthetic molecule of the pyridofuropyrimidine class [132]. PI-103 potently and selectively inhibited recombinant PI3K isoforms, p110α, p110β, and p110δ, as well as suppressed mTOR and DNA-PK. In addition, PI-103 showed inhibitory effects on cell proliferation and invasion of a wide variety of human cancer cells in vitro. In xenograft models, PI-103 inhibited tumor growth, invasion and angiogenesis as well [132]. In human leukemic cells and primary blast cells from acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients, PI-103 inhibited constitutive and growth factor-induced activation of PI3K/Akt and mTORC1 [133]. In human leukemic cell lines, PI-103 inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase. In blast cells, PI-103 induced apoptosis and inhibited the clonogenicity of AML progenitors, indicating the therapeutic value of PI-103 in AML [133]. In addition, PI-103 was demonstrated to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy and sensitize the chemotherapy-induced apoptosis [134,135]. In a panel of tumor cells with activation of survival signaling originating at the EGFR, or due to oncogenic mutation of RAS, PI-103 significantly reduced radiation survival of the cells [135]. Due to an aberrant activity of survival cascades, such as PI3K/Akt-mediated signaling, glioblastoma cells are considered to be highly resistant to conventional therapy [134]. PI-103 efficiently sensitized the cells for chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, not only in established glioblastoma cell lines but also in glioblastoma stem cells [134]. In primary glioblastoma cells derived from patients, PI-103 also significantly increased doxorubicin- and etoposide-induced apoptosis, further verifying the clinical relevance [134]. Obviously, these findings may have implications for rational design of the drug combination regimens to overcome the frequent chemoresistance of glioblastoma [134].

3.3. Selective mTORC1/2 inhibitors

A new generation of mTOR inhibitors, which compete with ATP in the catalytic site of mTOR, showed potent and selective inhibition on mTOR (Table 1). These molecules include PP242, PP30, Torin1, Ku-0063794, WAY-600, WYE-687 and WYE-354. Their chemical structures are shown in Fig. 2. Unlike PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors, they selectively inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 without inhibiting other kinases [136]. It was shown that these compounds potently inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 at nanomolar concentrations, as determined by S6K1 phosphorylation and Akt phosphorylation at S473, respectively [136-139]. Compared with rapamycin, PP242 and Torin1 impaired the proliferation of primary cells to a far greater degree [136,137]. It was assumed that the ability of PP242 and Torin1 to block cell proliferation more efficiently than rapamycin could be a result of its ability to inhibit mTORC2 in addition to mTORC1. However, In MEFs genetically deficient for mTORC2 activity, rapamycin was also less effective at blocking cell proliferation than PP242 and Torin1, suggesting the potent inhibitory effect of PP242 and Torin1 on cell proliferation is a result of more-complete mTORC1 inhibition, but not a consequence of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibition [136,137]. Consistently, both PP242 and Torin1 had much greater effects than rapamycin on 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and cap-dependent mRNA translation [136,137]. Moreover, both wild-type and rictor-null MEFs treated with Torin1, but not rapamycin, exhibited decreased protein expression of cyclin D1 and D3, and a profound induction of p27Kip1 [137]. These observations support the hypothesis that mTORC1 has rapamycin-resistant functions [136,137].

Ku-0063794, WAY-600, WYE-687 and WYE-354 (Fig. 2), which are most recently reported ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, also effectively inhibited both mTORC1 and mTORC2, as well as suppressed cell proliferation and induced a G1-cell cycle arrest in diverse cancer cell lines [138,139]. In nude mice bearing the PTEN-null PC3MM2 tumors, WYE-354 inhibited mTORC1 and mTORC2, and dose-dependently suppressed tumor growth [138].

Obviously, these mTOR kinase inhibitors have provided new tools for elucidating the novel roles of mTOR in tumorigenesis. However, more studies are still required to understand the distinct effects and mechanisms between these pharmacological agents and rapamycin in targeting cancer cell growth and survival, and to evaluate their efficacy in the treatment of cancer and other diseases in which PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is hyperactivated.

3.4. Diet-derived natural products

Increasing studies have demonstrated that some diet-derived natural products, including curcumin, resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), genistein, 3, 3-diindolylmethane (DIM) and caffeine, may inhibit mTOR signaling directly or indirectly (Table 1) [140-147].

EGCG, the most studied polyphenol component in green tea, is a potent antioxidant that may have therapeutic potential for many disorders including cancer. In the co-cultured keloid fibroblasts and HMC-1 cells, EGCG treatment dose-dependently reduced the increased phosphorylation of Akt, S6K and 4E-BP1 [143]. In both p53 positive and negative human hepatoma cells, EGCG activated AMPK, resulting in the suppression of downstream substrates, including mTOR and 4E-BP1, and a general decrease of mRNA translation [148].

Resveratrol is a polyphenolic flavonoid from grapes and red wine with potential anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective and anticancer properties [149]. In human U251 glioma cells, resveratrol downregulated PI3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated signaling pathway, and combination with rapamycin enhanced resveratrol-induced cell death [141]. In smooth muscle cells (SMC), resveratrol inhibited the proatherogenic oxidized LDL-induced activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/S6K pathway and remarkably suppressed DNA synthesis and proliferation of SMC [142]. Recently it has been described that resveratrol activated AMPK in both ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer cells, and consequently inhibited mTOR and its downstream 4E-BP1 signaling and mRNA translation. It was also found that the activation of AMPK by resveratrol was due to the induction of Sirtuin type 1 (SIRT1) expression in ER-positive breast cancer cells [150].

Increasing evidence suggested that curcumin may exert its antiproliferative effects by inhibiting mTOR signaling and thus may represent a new class of mTOR inhibitor. Curcumin is a polyphenol natural product isolated from the rhizome of the plant Curcuma longa and is undergoing early clinical trials as a novel anticancer agent [151]. Numerous studies have shown that curcumin inhibited the growth of a variety of cancer cells and showed effectiveness as a chemopreventive agent in animal models of carcinogenesis [152,153]. In our studies, we showed that curcumin inhibited cell growth, induced apoptosis and inhibited the basal or IGF-I-induced motility of rhabdomyosarcoma cells [154]. In numerous cancer cell lines, curcumin inhibited phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets, S6K1 and 4E-BP1, suggesting that curcumin may execute its anticancer effect primarily through blocking mTOR mediated signaling pathways [153,154]. Most recently, we further found that curcumin was able to dissociate raptor from mTOR, leading to inhibition of mTORC1 activity [140].

4. Summary and perspectives

Despite the discovery of mTOR for over 15 years, the complexity of the mTOR signaling network is just beginning to be understood. mTOR is a central controller of cell growth, proliferation, metabolism and angiogenesis. Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway is frequently observed in various human diseases, such as cancer and diabetes. Therefore, mTOR has received great attention for targeted therapy. Up to now, rapalogs are the most well studied mTOR inhibitors. In clinical trials, rapalogs showed potent antitumor activity in certain types of cancer and appear to be well tolerated. However, increasing evidence also revealed that the antiproliferative effects of rapalogs are variable among cancer cells. The specific inhibition of mTORC1 may induce PI3K-Akt upregulation, leading to the attenuation of the therapeutic effects of the rapalogs. Thus, the combination therapy or mTOR/PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors, such as GNE-477, NVP-BEZ235, PI-103 and XL765, may have improved antitumor activity.

Rapamycin, the first mTOR inhibitor discovered, has been an invaluable tool throughout the history of TOR research. Although rapamycin does not target the kinase domain of mTOR and the mechanism by which it inhibits mTOR is still not fully understood, rapamycin is widely accepted as selective inhibitor of mTORC1. Increasing studies of other mTOR kinase inhibitors, such as Torin1, PP242, and PP30, have suggested that mTORC1 might have rapamycin-resistant functions. Emergence of new class of mTOR inhibitors targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 has provided novel tools for elucidation of the roles of mTOR and marked the beginning of a new phase in mTOR-based therapeutic strategy. It is anticipated that this new class of mTOR inhibitors will be more effective and have broader applications. However, as those mTOR inhibitors are still in the early stage of evaluation, their therapeutic potential for cancer and other diseases remains largely uncertain. Undoubtedly, more new druggable mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitors will be developed in the future.

The diet-derived natural products are generally less toxic to human beings. Currently, all natural products tested, such as EGCG, curcumin and resveratrol, inhibit mTOR signaling at considerably high levels (micromolar ranges) in vitro. To achieve therapeutic effects in vivo, it is necessary to develop more potent derivatives of these natural products or effective formulations (e.g. nano-particles) with improved pharmaceutical properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors' work cited in this review was supported in part by NIH (CA115414 to S.H.) and American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE to S.H.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Targeting mTOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shamji AF, Nghiem P, Schreiber SL. Integration of growth factor and nutrient signaling: implications for cancer biology. Mol Cell. 2003;12:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty S, Mohiyuddin SM, Gopinath KS, Kumar A. Involvement of TSC genes and differential expression of other members of the mTOR signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darb-Esfahani S, Faggad A, Noske A, Weichert W, Buckendahl AC, Muller B, Budczies J, Roske A, Dietel M, Denkert C. Phospho-mTOR and phospho-4EBP1 in endometrial adenocarcinoma: association with stage and grade in vivo and link with response to rapamycin treatment in vitro. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenwald IB. The role of translation in neoplastic transformation from a pathologist's point of view. Oncogene. 2004;23:3230–3247. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekstrand AI, Jonsson M, Lindblom A, Borg A, Nilbert M. Frequent alterations of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan JA, Zhang H, Roberts PS, Jozwiak S, Wieslawa G, Lewin-Kowalik J, Kotulska K, Kwiatkowski DJ. Pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis subependymal giant cell astrocytomas: biallelic inactivation of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to mTOR activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1236–1242. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riemenschneider MJ, Betensky RA, Pasedag SM, Louis DN. AKT activation in human glioblastomas enhances proliferation via TSC2 and S6 kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5618–5623. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu G, Zhang W, Bertram P, Zheng XF, McLeod H. Pharmacogenomic profiling of the PI3K/PTEN-AKT-mTOR pathway in common human tumors. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:893–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helliwell SB, Wagner P, Kunz J, Deuter-Reinhard M, Henriquez R, Hall MN. TOR1 and TOR2 are structurally and functionally similar but not identical phosphatidylinositol kinase homologues in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:105–118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–468. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzieri DA, Feldman E, Dipersio JF, Gabrail N, Stock W, Strair R, Rivera VM, Albitar M, Bedrosian CL, Giles FJ. A phase 2 clinical trial of deforolimus (AP23573, MK-8669), a novel mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2756–2762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eynott PR, Salmon M, Huang TJ, Oates T, Nicklin PL, Chung KF. Effects of cyclosporin A and a rapamycin derivative (SAR943) on chronic allergic inflammation in sensitized rats. Immunology. 2003;109:461–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abizaid A, Lansky AJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Tanajura LF, Feres F, Staico R, Mattos L, Abizaid A, Chaves A, Centemero M, Sousa AG, Sousa JE, Zaugg MJ, Schwartz LB. Percutaneous coronary revascularization using a trilayer metal phosphorylcholine-coated zotarolimus-eluting stent. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1403–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rini BI. Temsirolimus, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1286–1290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolpin BM, Hezel AF, Abrams T, Blaszkowsky LS, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Enzinger PC, Allen B, Clark JW, Ryan DP, Fuchs CS. Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:193–198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369:756–758. doi: 10.1038/369756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Chen H, Rhoad AE, Warner L, Caggiano TJ, Failli A, Zhang H, Hsiao CL, Nakanishi K, Molnar-Kimber KL. A putative sirolimus (rapamycin) effector protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:1–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu MI, Katz H, Berlin V. RAPT1, a mammalian homolog of yeast Tor, interacts with the FKBP12/rapamycin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12574–12578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell. 1994;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keith CT, Schreiber SL. PIK-related kinases: DNA repair, recombination, and cell cycle checkpoints. Science. 1995;270:50–51. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, Deuter-Reinhard M, Movva NR, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell. 1993;73:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Latek RR, Guntur KV, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol Cell. 2003;11:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol Cell. 2007;25:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fingar DC, Blenis J. Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 2004;23:3151–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valentinis B, Baserga R. IGF-I receptor signalling in transformation and differentiation. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:133–137. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jefferies HB, Reinhard C, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Rapamycin selectively represses translation of the “polypyrimidine tract” mRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4441–4445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terada N, Patel HR, Takase K, Kohno K, Nairn AC, Gelfand EW. Rapamycin selectively inhibits translation of mRNAs encoding elongation factors and ribosomal proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11477–11481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of eIF4G. Mol Cell. 1999;3:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pause A, Belsham GJ, Gingras AC, Donze O, Lin TA, Lawrence JC, Jr, Sonenberg N. Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5′-cap function. Nature. 1994;371:762–767. doi: 10.1038/371762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, Ru B, Pan D. Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:699–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13571–13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202476899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manning BD, Cantley LC. Rheb fills a GAP between TSC and TOR. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Gao X, Saucedo LJ, Ru B, Edgar BA, Pan D. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:578–581. doi: 10.1038/ncb999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stocker H, Radimerski T, Schindelholz B, Wittwer F, Belawat P, Daram P, Breuer S, Thomas G, Hafen E. Rheb is an essential regulator of S6K in controlling cell growth in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:559–565. doi: 10.1038/ncb995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Ruegg MA, Hall A, Hall MN. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/ncb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barilli A, Visigalli R, Sala R, Gazzola GC, Parolari A, Tremoli E, Bonomini S, Simon A, Closs EI, Dall'Asta V, Bussolati O. In human endothelial cells rapamycin causes mTORC2 inhibition and impairs cell viability and function. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:563–571. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernandez-Negrete I, Carretero-Ortega J, Rosenfeldt H, Hernandez-Garcia R, Calderon-Salinas JV, Reyes-Cruz G, Gutkind JS, Vazquez-Prado J. P-Rex1 links mammalian target of rapamycin signaling to Rac activation and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23708–23715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hresko RC, Mueckler M. mTOR.RICTOR is the Ser473 kinase for Akt/protein kinase B in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40406–40416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klos KS, Wyszomierski SL, Sun M, Tan M, Zhou X, Li P, Yang W, Yin G, Hittelman WN, Yu D. ErbB2 increases vascular endothelial growth factor protein synthesis via activation of mammalian target of rapamycin/p70S6K leading to increased angiogenesis and spontaneous metastasis of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2028–2037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guertin DA, Guntur KV, Bell GW, Thoreen CC, Sabatini DM. Functional genomics identifies TOR-regulated genes that control growth and division. Curr Biol. 2006;16:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, Brown M, Fitzgerald KJ, Sabatini DM. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Martinez JM, Alessi DR. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1) Biochem J. 2008;416:375–385. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones KT, Greer ER, Pearce D, Ashrafi K. Rictor/TORC2 regulates Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage, body size, and development through sgk-1. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soukas AA, Kane EA, Carr CE, Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2009;23:496–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.1775409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vezina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:721–726. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vezina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:727–732. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eng CP, Sehgal SN, Vezina C. Activity of rapamycin (AY-22,989) against transplanted tumors. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1984;37:1231–1237. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Douros J, Suffness M. New antitumor substances of natural origin. Cancer Treat Rev. 1981;8:63–87. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(81)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Linhares MM, Gonzalez AM, Trivino T, Melaragno C, Moura RM, Garcez MH, Sa JR, Aguiar WF, Succi T, Barbosa CS, Pestana JO. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation initial experience. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1109. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yatscoff RW, LeGatt DF, Kneteman NM. Therapeutic monitoring of rapamycin: a new immunosuppressive drug. Ther Drug Monit. 1993;15:478–482. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Resistance to rapamycin: a novel anticancer drug. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:69–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1013167315885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen J, Zheng XF, Brown EJ, Schreiber SL. Identification of an 11-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin-binding domain within the 289-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein and characterization of a critical serine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4947–4951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kunz J, Hall MN. Cyclosporin A, FK506 and rapamycin: more than just immunosuppression. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:334–338. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science. 1996;273:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oshiro N, Yoshino K, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Hara K, Eguchi S, Avruch J, Yonezawa K. Dissociation of raptor from mTOR is a mechanism of rapamycin-induced inhibition of mTOR function. Genes Cells. 2004;9:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Foster DA, Toschi A. Targeting mTOR with rapamycin: one dose does not fit all. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1026–1029. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toschi A, Lee E, Xu L, Garcia A, Gadir N, Foster DA. Regulation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complex assembly by phosphatidic acid: competition with rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00782-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dilling MB, Dias P, Shapiro DN, Germain GS, Johnson RK, Houghton PJ. Rapamycin selectively inhibits the growth of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma cells through inhibition of signaling via the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1994;54:903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hosoi H, Dilling MB, Shikata T, Liu LN, Shu L, Ashmun RA, Germain GS, Abraham RT, Houghton PJ. Rapamycin causes poorly reversible inhibition of mTOR and induces p53-independent apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geoerger B, Kerr K, Tang CB, Fung KM, Powell B, Sutton LN, Phillips PC, Janss AJ. Antitumor activity of the rapamycin analog CCI-779 in human primitive neuroectodermal tumor/medulloblastoma models as single agent and in combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1527–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seufferlein T, Rozengurt E. Rapamycin inhibits constitutive p70s6k phosphorylation, cell proliferation, and colony formation in small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3895–3897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogawa T, Tokuda M, Tomizawa K, Matsui H, Itano T, Konishi R, Nagahata S, Hatase O. Osteoblastic differentiation is enhanced by rapamycin in rat osteoblast-like osteosarcoma (ROS 17/2.8) cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:226–230. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grewe M, Gansauge F, Schmid RM, Adler G, Seufferlein T. Regulation of cell growth and cyclin D1 expression by the constitutively active FRAP-p70s6K pathway in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3581–3587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van der Poel HG, Hanrahan C, Zhong H, Simons JW. Rapamycin induces Smad activity in prostate cancer cell lines. Urol Res. 2003;30:380–386. doi: 10.1007/s00240-002-0282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pang H, Faber LE. Estrogen and rapamycin effects on cell cycle progression in T47D breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;70:21–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1012570204923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busca R, Bertolotto C, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/p70(S6)-kinase pathway induces B16 melanoma cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31824–31830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muthukkumar S, Ramesh TM, Bondada S. Rapamycin, a potent immunosuppressive drug, causes programmed cell death in B lymphoma cells. Transplantation. 1995;60:264–270. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199508000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Humar R, Kiefer FN, Berns H, Resink TJ, Battegay EJ. Hypoxia enhances vascular cell proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent signaling. Faseb J. 2002;16:771–780. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0658com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, Koehl G, Flegel S, Hornung M, Bruns CJ, Zuelke C, Farkas S, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Geissler EK. Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by antiangiogenesis: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:128–135. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ballou LM, Lin RZ. Rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors. J Chem Biol. 2008;1:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s12154-008-0003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dudkin L, Dilling MB, Cheshire PJ, Harwood FC, Hollingshead M, Arbuck SG, Travis R, Sausville EA, Houghton PJ. Biochemical correlates of mTOR inhibition by the rapamycin ester CCI-779 and tumor growth inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1758–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Temsirolimus: CCI 779, CCI-779, cell cycle inhibitor-779. Drugs R D. 2004;5:363–367. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200405060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Discafani C, Zhang WG, Skotnicki J, Frost P, Gibbons JJ. mTOR, a novel target in breast cancer: the effect of CCI-779, an mTOR inhibitor, in preclinical models of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:249–258. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Asano T, Yao Y, Zhu J, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Reddy SA. The rapamycin analog CCI-779 is a potent inhibitor of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ekshyyan O, Rong Y, Rong X, Pattani KM, Abreo F, Caldito G, Chang JK, Ampil F, Glass J, Nathan CA. Comparison of radiosensitizing effects of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor CCI-779 to cisplatin in experimental models of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2255–2265. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raymond E, Alexandre J, Faivre S, Vera K, Materman E, Boni J, Leister C, Korth-Bradley J, Hanauske A, Armand JP. Safety and pharmacokinetics of escalated doses of weekly intravenous infusion of CCI-779, a novel mTOR inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2336–2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:671–688. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, Logan TF, Dutcher JP, Hudes GR, Park Y, Liou SH, Marshall B, Boni JP, Dukart G, Sherman ML. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:909–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hidalgo M, Buckner JC, Erlichman C, Pollack MS, Boni JP, Dukart G, Marshall B, Speicher L, Moore L, Rowinsky EK. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) administered intravenously daily for 5 days every 2 weeks to patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5755–5763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, Greenberg H, Schiff D, Conrad C, Fink K, Robins HI, De Angelis L, Raizer J, Hess K, Aldape K, Lamborn KR, Kuhn J, Dancey J, Prados MD. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Galanis E, Buckner JC, Maurer MJ, Kreisberg JI, Ballman K, Boni J, Peralba JM, Jenkins RB, Dakhil SR, Morton RF, Jaeckle KA, Scheithauer BW, Dancey J, Hidalgo M, Walsh DJ. Phase II trial of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5294–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.23.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, Inwards DJ, Fonseca R, Kurtin P, Ansell SM, Luyun R, Flynn PJ, Morton RF, Dakhil SR, Gross H, Kaufmann SH. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5347–5356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Margolin K, Longmate J, Baratta T, Synold T, Christensen S, Weber J, Gajewski T, Quirt I, Doroshow JH. CCI-779 in metastatic melanoma: a phase II trial of the California Cancer Consortium. Cancer. 2005;104:1045–1048. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Duran I, Kortmansky J, Singh D, Hirte H, Kocha W, Goss G, Le L, Oza A, Nicklee T, Ho J, Birle D, Pond GR, Arboine D, Dancey J, Aviel-Ronen S, Tsao MS, Hedley D, Siu LL. A phase II clinical and pharmacodynamic study of temsirolimus in advanced neuroendocrine carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chan S, Scheulen ME, Johnston S, Mross K, Cardoso F, Dittrich C, Eiermann W, Hess D, Morant R, Semiglazov V, Borner M, Salzberg M, Ostapenko V, Illiger HJ, Behringer D, Bardy-Bouxin N, Boni J, Kong S, Cincotta M, Moore L. Phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779), a novel inhibitor of mTOR, in heavily pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5314–5322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pandya KJ, Dahlberg S, Hidalgo M, Cohen RB, Lee MW, Schiller JH, Johnson DH. A randomized, phase II trial of two dose levels of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer who have responding or stable disease after induction chemotherapy: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E1500) J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:1036–1041. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318155a439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, Staroslawska E, Sosman J, McDermott D, Bodrogi I, Kovacevic Z, Lesovoy V, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Barbarash O, Gokmen E, O'Toole T, Lustgarten S, Moore L, Motzer RJ. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hess G, Herbrecht R, Romaguera J, Verhoef G, Crump M, Gisselbrecht C, Laurell A, Offner F, Strahs A, Berkenblit A, Hanushevsky O, Clancy J, Hewes B, Moore L, Coiffier B. Phase III study to evaluate temsirolimus compared with investigator's choice therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3822–3829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kirchner GI, Meier-Wiedenbach I, Manns MP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of everolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:83–95. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Augustine JJ, Hricik DE. Experience with everolimus. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:500S–503S. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schuler W, Sedrani R, Cottens S, Haberlin B, Schulz M, Schuurman HJ, Zenke G, Zerwes HG, Schreier MH. SDZ RAD, a new rapamycin derivative: pharmacological properties in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation. 1997;64:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boulay A, Zumstein-Mecker S, Stephan C, Beuvink I, Zilbermann F, Haller R, Tobler S, Heusser C, O'Reilly T, Stolz B, Marti A, Thomas G, Lane HA. Antitumor efficacy of intermittent treatment schedules with the rapamycin derivative RAD001 correlates with prolonged inactivation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:252–261. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-3554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gabardi S, Cerio J. Future immunosuppressive agents in solid-organ transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2004;14:148–156. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin as novel antitumor agents: from bench to clinic. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.O'Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA, 3rd, Rea D, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shand N, Lane HA, Hazell K, Zoellner U, Kovarik JM, Brock C, Jones S, Raymond E, Judson I. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1588–1595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tanaka C, O'Reilly T, Kovarik JM, Shand N, Hazell K, Judson I, Raymond E, Zumstein-Mecker S, Stephan C, Boulay A, Hattenberger M, Thomas G, Lane HA. Identifying optimal biologic doses of everolimus (RAD001) in patients with cancer based on the modeling of preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1596–1602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tabernero J, Rojo F, Calvo E, Burris H, Judson I, Hazell K, Martinelli E, Ramon y Cajal S, Jones S, Vidal L, Shand N, Macarulla T, Ramos FJ, Dimitrijevic S, Zoellner U, Tang P, Stumm M, Lane HA, Lebwohl D, Baselga J. Dose- and schedule-dependent inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway with everolimus: a phase I tumor pharmacodynamic study in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1603–1610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Amato RJ, Jac J, Giessinger S, Saxena S, Willis JP. A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:2438–2446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grunwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N, Urbanowitz G, Berg WJ, Kay A, Lebwohl D, Ravaud A. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bellmunt J, Szczylik C, Feingold J, Strahs A, Berkenblit A. Temsirolimus safety profile and management of toxic effects in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and poor prognostic features. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1387–1392. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Agarwala SS, Case S. Everolimus (RAD001) in the Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Review. Oncologist. 15:236–245. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mita MM, Mita AC, Chu QS, Rowinsky EK, Fetterly GJ, Goldston M, Patnaik A, Mathews L, Ricart AD, Mays T, Knowles H, Rivera VM, Kreisberg J, Bedrosian CL, Tolcher AW. Phase I trial of the novel mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor deforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) administered intravenously daily for 5 days every 2 weeks to patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:361–367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mita M, Sankhala K, Abdel-Karim I, Mita A, Giles F. Deforolimus (AP23573) a novel mTOR inhibitor in clinical development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1947–1954. doi: 10.1517/13543780802556485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hartford CM, Desai AA, Janisch L, Karrison T, Rivera VM, Berk L, Loewy JW, Kindler H, Stadler WM, Knowles HL, Bedrosian C, Ratain MJ. A phase I trial to determine the safety, tolerability, and maximum tolerated dose of deforolimus in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1428–1434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mita MM, Britten CD, Poplin E, Tap WD, Carmona A, Yonemoto L, Wages DS, Bedrosian CL, Rubin EH, Tolcher AW. Deforolimus trial 106- A Phase I trial evaluating 7 regimens of oral Deforolimus (AP23573, MK-8669). American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; Chicago, Illinois. May 30-June 3, 2008; Abstract 3509. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fetterly GJ, Mita MM, Britten CD, Poplin E, Tap WD, Carmona A, Yonemoto L, Bedrosian CL, Rubin EH, Tolcher AW. Pharmacokinetics of oral deforolimus (AP23573, MK-8669). American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; Chicago, Illinois. May 30-June 3, 2008; Abstract 14555. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sessa C, Tosi D, Vigano L, Albanell J, Hess D, Maur M, Cresta S, Locatelli A, Angst R, Rojo F, Coceani N, Rivera VM, Berk L, Haluska F, Gianni L. Phase Ib study of weekly mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor ridaforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) with weekly paclitaxel. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1315–1322. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Heffron TP, Berry M, Castanedo G, Chang C, Chuckowree I, Dotson J, Folkes A, Gunzner J, Lesnick JD, Lewis C, Mathieu S, Nonomiya J, Olivero A, Pang J, Peterson D, Salphati L, Sampath D, Sideris S, Sutherlin DP, Tsui V, Wan NC, Wang S, Wong S, Zhu BY. Identification of GNE-477, a potent and efficacious dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 20:2408–2411. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Brachmann S, Chene P, De Pover A, Schoemaker K, Fabbro D, Gabriel D, Simonen M, Murphy L, Finan P, Sellers W, Garcia-Echeverria C. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zou ZQ, Zhang XH, Wang F, Shen QJ, Xu J, Zhang LN, Xing WH, Zhuo RJ, Li D. A novel dual PI3Kalpha/mTOR inhibitor PI-103 with high antitumor activity in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:97–101. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Molckovsky A, Siu LL. First-in-class, first-in-human phase I results of targeted agents: Highlights of the 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2008;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li T, Jia W, Wang X, Yang N, Chen SM, Tong LJ, Yang CH, Meng LH, Ding J. WJD008, a Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, Prevents PI3K Signaling and Inhibits the Proliferation of Transformed Cells with Oncogenic PI3K mutant. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:830–838. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, Lane H, Hofmann F, Hicklin DJ, Ludwig DL, Baselga J, Rosen N. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Serra V, Markman B, Scaltriti M, Eichhorn PJ, Valero V, Guzman M, Botero ML, Llonch E, Atzori F, Di Cosimo S, Maira M, Garcia-Echeverria C, Parra JL, Arribas J, Baselga J. NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the growth of cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8022–8030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cao P, Maira SM, Garcia-Echeverria C, Hedley DW. Activity of a novel, dual PI3-kinase/mTor inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 against primary human pancreatic cancers grown as orthotopic xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Baumann P, Mandl-Weber S, Oduncu F, Schmidmaier R. The novel orally bioavailable inhibitor of phosphoinositol-3-kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin, NVP-BEZ235, inhibits growth and proliferation in multiple myeloma. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]