Abstract

Recent data suggest that a functional cooperation between surfactant proteins SP-B and SP-C may be required to sustain a proper compression-expansion dynamics in the presence of physiological proportions of cholesterol. SP-C is a dually palmitoylated polypeptide of 4.2 kDa, but the role of acylation in SP-C activity is not completely understood. In this work we have compared the behavior of native palmitoylated SP-C and recombinant nonpalmitoylated versions of SP-C produced in bacteria to get a detailed insight into the importance of the palmitic chains to optimize interfacial performance of cholesterol-containing surfactant films. We found that palmitoylation of SP-C is not essential for the protein to promote rapid interfacial adsorption of phospholipids to equilibrium surface tensions (∼22 mN/m), in the presence or absence of cholesterol. However, palmitoylation of SP-C is critical for cholesterol-containing films to reach surface tensions ≤1 mN/m at the highest compression rates assessed in a captive bubble surfactometer, in the presence of SP-B. Interestingly, the ability of SP-C to facilitate reinsertion of phospholipids during expansion was not impaired to the same extent in the absence of palmitoylation, suggesting the existence of palmitoylation-dependent and -independent functions of the protein. We conclude that palmitoylation is key for the functional cooperation of SP-C with SP-B that enables cholesterol-containing surfactant films to reach very low tensions under compression, which could be particularly important in the design of clinical surfactants destined to replacement therapies in pathologies such as acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Introduction

Breathing and lung mechanics critically depend on a great variety of lipid/lipid and lipid/protein interactions that occur in pulmonary surfactant, a lipid/protein complex that lines the inner surface of the lung and functions to reduce the surface tension at the air/liquid interface in order to minimize the work of breathing (1,2). The lack or dysfunction of an active surfactant results in severe respiratory disorders, such as neonatal respiratory distress syndrome or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) associated with lung injury (3).

In order to fulfill its function, pulmonary surfactant has been evolutionarily optimized to contain ∼80–85% of phospholipids, with approximately one-half of them being DPPC (dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine), 5–10% neutral lipids, mainly cholesterol, and 6–8% specific surfactant-associated proteins. DPPC, the major lipid species in lung surfactant, and the two small hydrophobic surfactant proteins SP-B and SP-C have emerged as the most critical components for a functional surfactant (2). DPPC is absolutely necessary for surfactant films to reach very low surface tensions (≤1 mN/m) upon compression. On the other hand, SP-B and SP-C have been shown to be required for efficient interfacial adsorption, film stability, and respreading of the surfactant film upon expansion (4). The combination of these properties is pivotal for the dynamic behavior of surfactant films during repeated cycles of compression and expansion throughout breathing in vivo (5).

SP-C is the smallest of the surfactant-associated proteins. Mature SP-C consists of a C-terminal, very hydrophobic α-helix and a dually palmitoylated N-terminal segment (6). Although SP-C is not absolutely critical for survival, SP-C (−/−) mice develop progressive pneumonitis of different degrees depending on the genetic background (7). In vitro data indicate that SP-C is required to maintain surfactant reservoirs attached to the interface during states of high compression, at the end of expiration (8). These reservoirs could then reinsert rapidly under the critical participation of SP-B. The palmitoylation of SP-C has been proposed to be important for the stabilization of the reservoirs (9,10).

Despite the presence of 5–10% by total mass of cholesterol in pulmonary surfactant, cholesterol has been regarded as detrimental for proper lung function. In vitro data suggest severe structural changes in surfactant films in the presence of high concentrations (20%) of cholesterol (11), and clinical surfactant substitutes do not usually contain cholesterol (12). Furthermore, the presence of exacerbated levels of cholesterol has been implicated in the pathology of ARDS and other diseases (13). Nevertheless, cholesterol has been shown to modulate molecular dynamics of phospholipids in surfactant complexes (14). In fact, cholesterol levels in surfactant are tightly controlled and are regulated in some species in response to temperature changes (15). Recent reports have shown that SP-B and SP-C can cooperate to counteract the deleterious effects of cholesterol on surfactant film stability during continuous cycling (16).

In this article, we investigate the role of palmitoylation of SP-C for the cooperation with SP-B to stabilize cholesterol-containing surfactant films subjected to compression/expansion dynamics in a captive bubble surfactometer (CBS). By comparing native palmitoylated SP-C with recombinant (nonpalmitoylated) versions of the protein, we show that the presence of the palmitic chains is critical for SP-C to cooperate with SP-B in this function. The present data, therefore, refine the concept of how SP-B and SP-C might cooperate in vivo to enable proper functioning of cholesterol-containing pulmonary surfactant.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

DPPC, (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)]), and cholesterol were all from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Chloroform and methanol solvents, HPLC grade, were from Scharlau (Barcelona, Spain). Native surfactant proteins SP-B and SP-C were isolated from minced porcine lungs as described elsewhere (17).

Recombinant protein purification

For the production of different recombinant SP-C versions, we essentially followed the procedures described by Lukovic et al. (18). Recombinant protein quality was controlled by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, mass spectrometry and amino-acid analysis. Table S1 in the Supporting Material summarizes and compares the sequences of the produced proteins. Due to the purification procedures that involve a thrombin digestion at an optimized cleavage site to yield recombinant SP-C from the fusion protein, most of the recombinant SP-C variants used here contain an N-terminal GP extension. Previously, we had not found significant structural or functional differences between recombinant forms bearing or not bearing these extensions (18). Nevertheless, some of the experiments shown in this study were also repeated with SP-C versions that do not contain the GP extension, and their behavior was again found to be completely comparable, as it will be described. Because final protein yield is much higher for the GP-containing SP-C versions, unless otherwise stated the recombinant protein used in the experiments was produced with this dipeptide-extension.

Reconstitution of lipid and lipid/protein samples

The standard lipid mixture used in this study to reconstitute pulmonary surfactant model suspensions contained DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w). This mixture simulates the proportion of saturated/unsaturated and zwitterionic/anionic phospholipids in surfactant. When indicated, the samples contained 5% cholesterol to mimic the physiological surfactant composition. Multilamellar suspensions were prepared by mixing the appropriate amount of protein and lipids in chloroform/methanol 2:1, drying the samples overnight under vacuum, and resuspending them at 45°C in the desired final volume of sample buffer (5 mM Tris,150 mM HCl buffer, pH 7.0) for 1.5 h and shaking. The lipid suspensions were generally prepared at a final concentration of 10 mg/mL.

Captive bubble surfactometry

The surface activity of the model surfactant mixtures was assessed in a computer-controlled captive bubble surfactometer (CBS) operated as described previously (16). This device, described in detail elsewhere (19,20), allows a reliable and reproducible estimation of the surface tension of surfactant films subjected to compression/expansion dynamics. The CBS chamber, thermostated at 37°C, was filled with ∼1.5 mL of sample buffer (5 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0) containing 10% w/w sucrose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), in order to increase its density, and contained originally no surfactant. Then the surfactant sample was accurately measured and injected, using a micropositioning device, at the proximity of the bubble surface. The high density of the bulk solution induces surfactant suspensions to float and remain in close contact with the bubble upon injection (see Fig. S1). The presence of sucrose does not affect surface activity of surfactant (21).

A small air bubble (∼2 mm in diameter, 50 μL) was introduced into the chamber after degassing the buffer solution and allowed to float up to the agarose ceiling. Then, ∼0.5 μL of lipid or lipid/protein surfactant suspension (10 mg/mL) were deposited directly at the air/buffer interface of the bubble by means of a transparent capillary. The bubble was imaged with a video camera (Pulnix TM 7 CN; JAI-PULNiX, Glostrup, Denmark) and recorded for later analysis. A 5-min adsorption (film formation) period followed the introduction of the surfactant model suspensions into the chamber, during which the bubble was not manipulated and the change in surface tension was monitored (initial adsorption). The chamber was then sealed and the bubble was rapidly (1 s) expanded to a volume of 0.15 mL and changes in surface tension were monitored during 5 min (postexpansion adsorption). Because the size of the bubble is increased significantly, postexpansion adsorption also evaluates how efficiently a surplus of surfactant has maintained association with the interface, after initial injection, to refill the new opening surface. Then, quasistatic cycling was initiated, where the bubble size was first reduced and then enlarged in a stepwise fashion.

Each step had two components: a 3 s change in volume followed by a 4 s delay where the chamber volume remained unchanged and the film was allowed to equilibrate. Under these conditions, interfacial structures could relax along the compression-expansion isotherms. Compression was always stopped when minimum surface tension was obtained, before the collapse of the film would lead to a variable level of overcompression. The collapse point at which overcompression can be prevented was judged visually, when the height of the bubble does not change upon further compression but the bubble shrinks in diameter instead. In the dynamic cycles, the bubble size was continuously compressed and expanded over the same volume range as during the quasistatic cycles for 20 cycles at a rate of 20 cycles/min (roughly in the range of the respiration rate of the lung). For all imaged bubbles, volume, interfacial area, and surface tension were calculated using height and diameter of the bubble as previously described (16,22). Fig. S2 compares the waveform of area and volume oscillations under quasistatic and dynamic conditions. At least four independent experiments were performed for each surfactant model suspension, using at least two different batches of purified protein, with qualitatively comparable results. Data from adsorption experiments are presented as means ± SD. Compression-expansion isotherms are representative experiments.

Results

To get new insights into the role of palmitoylation in SP-C, we compared native palmitoylated SP-C purified from porcine lungs with two different recombinant versions of SP-C that were produced in Escherichia coli. One of them reflects the wild-type sequence of human mature SP-C. Because bacteria lack the mammalian palmitoylation machinery, this recombinant SP-C form (i.e., rSP-C CC) displays two free cysteines at positions 5 and 6 of the sequence (Table S1). Mass spectrometry and electrophoretic analysis confirm that this protein stably maintains the cysteines in their reduced form during storage and during the periods of time in which our experiments were carried out. The other recombinant SP-C variant studied contained two phenylalanine residues substituting for the cysteines (i.e., rSP-C FF). The rationale for choosing this replacement was that in several animals, one of the two cysteines in SP-C is substituted by phenylalanine (23). rSPC FF has therefore been proposed as a potentially functional equivalent to wild-type SP-C in clinical preparations.

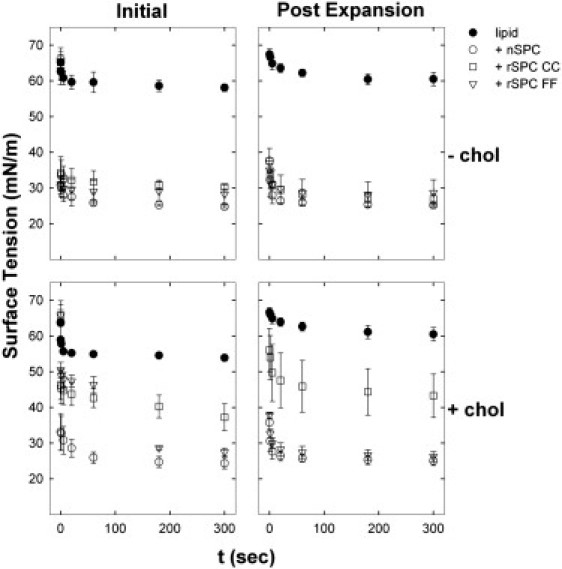

In a first series of experiments, we investigated how palmitoylation could affect the surface activity of the protein. To this end, we analyzed the behavior in a CBS of DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) suspensions containing 5% cholesterol or not, in the absence or presence of 1% of native or recombinant SP-Cs. Fig. 1 shows the time-dependent reduction of surface tension upon adsorption of the different lipid or lipid/protein samples at the air-liquid interface of an air bubble (initial adsorption) or after expansion of the bubble (adsorption postexpansion). Initial adsorption includes association of injected complexes to the bubble surface and transfer of surface active molecules into the interface. Postexpansion adsorption to a bubble which has been considerably enlarged also evaluates the ability of the surplus of surfactant initially injected to form a surface-associated reservoir ready to refill the newly open interface.

Figure 1.

Initial and postexpansion adsorption in the presence of SP-C. The effect of native and recombinant SP-C on the interfacial adsorption kinetics of lipid suspensions composed of DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) was measured in the absence (upper panels) or presence (lower panels) of 5% w/w cholesterol. (Left) Decrease of surface tension over time during the first 5 min after deposition of ∼0.5 μL of the different lipid or lipid/protein samples (10 mg/mL). (Right) Decrease in surface tension monitored during 5 min after expansion of the bubble from a volume of ∼0.045–0.15 mL. Data are means ± SD after averaging data from three independent experiments.

In the absence of protein, purely lipidic suspensions showed very limited interfacial adsorption to equilibrium tensions that were barely lower than 55 mN/m, regardless of the presence of cholesterol. In contrast, for samples containing 2% of any of the SP-C forms exhibited, in the absence of cholesterol there was an almost instantaneous drop of surface tension to below 30 mN/m. Palmitoylation, therefore, does not seem to be required for SP-C to promote efficient interfacial adsorption in the absence of cholesterol. Surprisingly though, in the presence of 5% cholesterol, while samples containing palmitoylated SP-C still reached low tensions both right after sample deposition and after expansion, samples with rSP-C CC produced much less surface tension reduction. rSPC FF behaved similar to native SP-C, although the reduction in surface tension at initial adsorptions was somewhat slower. rSP-C CC performed worse both in initial and postexpansion adsorption, producing tensions not lower than ∼40 mN/m. This would indicate that, in the presence of cholesterol, phenylalanines are able to mimic to a certain degree the effects of the palmitic chains in their role in adsorption, while the free cysteines are not.

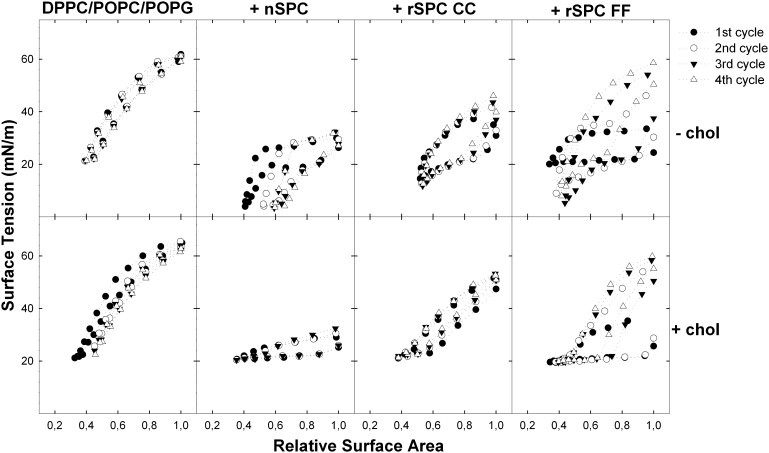

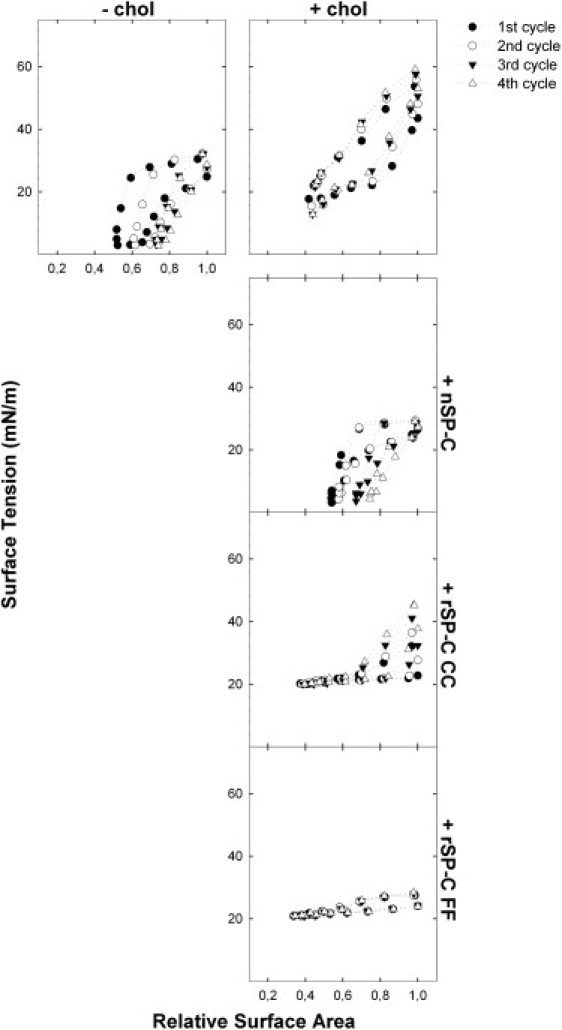

Fig. 2 shows quasistatic cycling of surfactant films containing native or recombinant SP-C as the single protein component, in the presence or absence of cholesterol. Controls were performed with pure lipid films. In the absence of any protein, surfactant films cannot reach upon compression surface tensions lower than the equilibrium tension of ∼22 mN/m and show a very high maximum surface tension, indicating that the material is not efficiently respreading into the interface upon expansion. In the absence of cholesterol, 2% of native SP-C was sufficient to allow the films reaching tensions close to 0 mN/m with efficient respreading (Fig. 2, upper panels), as revealed by the low maximal tensions. However, considerable compression/expansion hysteresis, especially during the first two cycles, reflects low stability of the compressed phases.

Figure 2.

Quasistatic compression/expansion isotherms in the presence of SP-C. Films formed from DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) suspensions in the absence (upper panels) or presence (lower panels) of 5% (w/w) cholesterol and containing no protein (left), or 2% (w/w) of native SP-C (central left), rSP-C CC (central right), or SP-C FF (right) were subjected to quasistatic cycling. The surface-tension-versus-relative-area is plotted for the four consecutive stepwise compression-expansion isotherms.

Furthermore, a pronounced plateau at ∼20 mN/m is clearly visible before the compressed film reaches the lowest surface tensions. This plateau has been associated with compression-driven three-dimensional transitions, likely facilitated by SP-C, taking the film to configurations able to support the maximal surface pressures (minimal tensions) without collapsing (24). In this respect, recombinant versions of SP-C reproduce only partly the behavior of native SP-C. Samples containing rSP-C CC produce lower minimal tensions than pure lipidic samples but do not reach as low values as the samples containing native palmitoylated protein. This recombinant SP-C produced also maximal tensions that were intermediate between those reached by pure lipid and the low maximal tensions maintained by the native protein. The rSP-C FF variant, on the other hand, displays a behavior somehow closer to the native palmitoylated protein, as it allows reaching the lowest surface tensions while respreading is still impaired.

In the presence of cholesterol, none of the SP-C versions tested could lead by themselves to a substantial reduction in surface tension upon compression compared to pure lipid films. Presence of the protein led to the appearance of large compression plateaus, at ∼20 mN/m, which did not progress to a further reduction in tension, as observed in the absence of cholesterol (Fig. 2, bottom panels). The fluidizing effect of cholesterol may prevent compression of the surfactant film to states compatible with further reduction of surface tension. It is noteworthy that native palmitoylated SP-C is significantly more efficient in promoting respreading of the films upon expansion also in the presence of cholesterol, as can be seen in the considerably lower maximum surface tension reached in the presence of native SP-C.

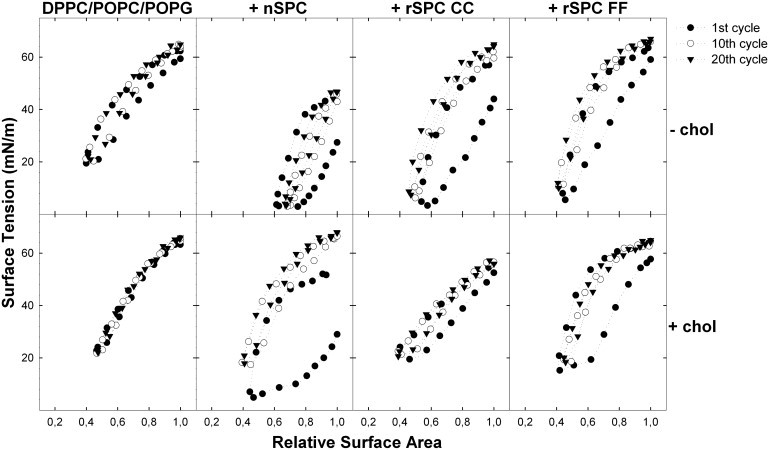

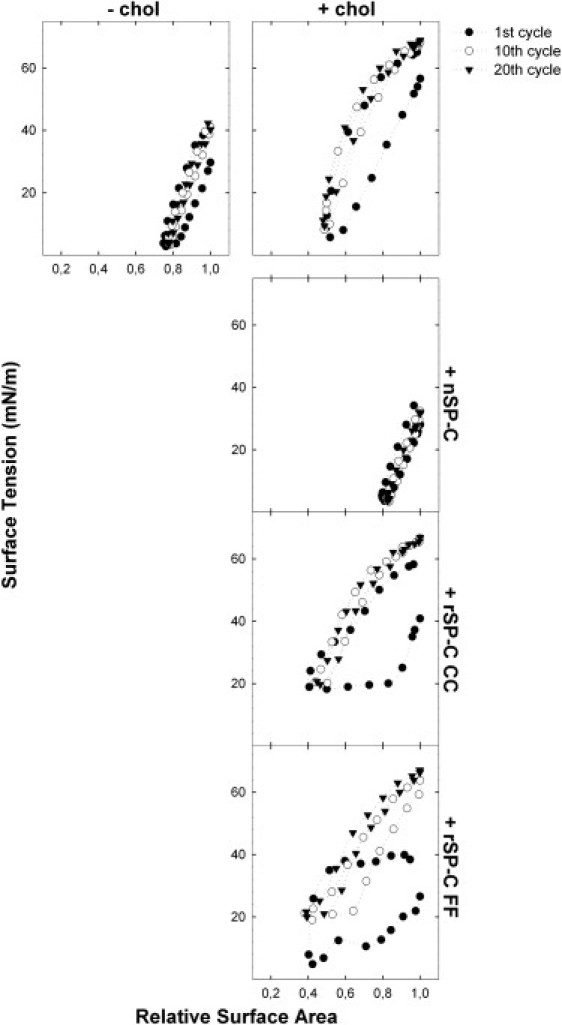

Fig. 3 shows dynamic cycling (at 20 cycles/min) of the same surfactant films described in Fig. 2. In the absence of cholesterol, all the films containing protein were able to reach very low surface tensions, irrespective of the SP-C version used (Fig. 3, upper panels). The rapid compression/expansion rate used during dynamic cycling probably prevents reorganization of the film such as occurs upon the stepwise compression and expansion applied in quasistatic cycles. This effect may explain why some films are able to reach lower tensions during rapid dynamic cycling than under quasistatic conditions. A kinetic effect is probably also associated with differences in the reinsertion of lipids upon reexpansion. During rapid cycling there is not enough time for reinsertion, increasing the differences between proteins that promote respreading with different efficacies. Maximal tensions are higher for films cycled under dynamic conditions, with only native SP-C reducing significantly the maximal tension in the absence of cholesterol. Cholesterol has again a general impairing effect on the ability of the films to reach low surface tension during dynamic cycling, irrespective of the presence of SP-C (Fig. 3, bottom panels).

Figure 3.

Dynamic compression-expansion isotherms in the presence of SP-C. Films formed from DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) suspensions in the absence (upper panels) or presence (lower panels) of 5% (w/w) cholesterol and containing no protein (left), or 2% (w/w) of native SP-C (central left), rSP-C CC (central right), or rSP-C FF (right) were subjected to dynamic cycling at a rate of 20 cycles/min. The surface-tension-versus-relative-area is plotted for the first, 10th, and 20th cycle of continuous compression-expansion isotherms.

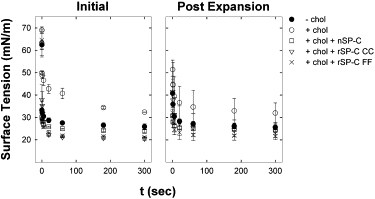

Previous work of our group revealed a cooperative effect of SP-B and SP-C that could alleviate the deleterious effects of cholesterol on the surface activity of surfactant films (16). We therefore wanted to explore whether recombinant versions of SP-C could mimic native SP-C in this effect. First, we compared the behavior of samples containing 1% w/w SP-B as the only protein component, in the presence or absence of 5% w/w cholesterol. Measurements of initial and postexpansion adsorption showed that cholesterol impaired the ability of these samples to rapidly reach low surface tensions as compared to the samples that did not contain cholesterol (Fig. 4). Inclusion of 2% (w/w) of SP-C, however, improved adsorption in the presence of cholesterol significantly, as shown in Fig. 4, independently of the form of SP-C used. While recombinant nonpalmitoylated SP-C is indistinguishable from native palmitoylated SP-C in its ability to promote adsorption in the presence of cholesterol, clear differences became apparent when the surfactant films were subjected to quasistatic or dynamic compression/expansion cycling. Quasistatic cycles of films containing 5% (w/w) cholesterol, 1% (w/w) of native SP-B, and 2% (w/w) of either native or recombinant SP-C are shown in Fig. 5. Cholesterol drastically impairs the ability of SP-B-containing surfactant films to reach very low surface tensions upon compression.

Figure 4.

Initial and postexpansion adsorption in the presence of cholesterol, SP-B, and SP-C. The effect of native and recombinant SP-C on the interfacial adsorption kinetics of lipid suspensions composed of DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15:10, w/w/w) plus 1% (w/w) porcine SP-B was evaluated in the presence of 5% w/w cholesterol. (Left panel) Initial adsorption (recorded during 5 min after deposition of the respective lipid samples. (Right panel) Postexpansion adsorption(decrease in surface tension during 5 min after expansion of the bubble to a volume of 0.15 mL. The samples, with 1% (w/w) of SP-B, contained no cholesterol, 5% (w/w) cholesterol, or 5% (w/w) cholesterol plus 2% (w/w) native SP-C, rSP-C CC, or rSP-C FF. Data are means ± SD after averaging data from three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Quasistatic cycling and SP-B/SP-C cooperation in cholesterol-containing surfactant films. Films formed from DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) suspensions containing 1% w/w SP-B and no cholesterol (top left) or containing 5% (w/w) cholesterol (right panels) were subjected to quasistatic cycling in the absence of SP-C (top), or in the presence of 2% (w/w) of native SP-C (upper center), rSP-C CC (lower center), or SP-C FF (bottom). The surface-tension-versus-relative-area is plotted for the first, second, third, and fourth cycle of four consecutive stepwise compression-expansion isotherms.

Strikingly, the presence of palmitoylated SP-C counteracts this deleterious effect of cholesterol (Fig. 5, left panel), confirming recently published results (16). In contrast, cholesterol-containing films including nonpalmitoylated recombinant forms of SP-C are unable to reach surface tensions below ∼20mN/m. Interestingly, the ability of SP-C to facilitate respreading of the films upon expansion, as can be inferred from the maximum surface tensions reached upon cycling, is retained in the presence of nonpalmitoylated SP-C, both in the case of rSP-C CC and rSP-C FF. The palmitic chains therefore do not seem to be relevant for this function of SP-C, at least in the presence of SP-B (see Discussion). Note that rSP-C FF is slightly more efficient in lowering the maximum surface tension, supporting the role of the phenylalanines in partly mimicking the palmitoylcysteines.

Fig. 6 shows dynamic cycling of the same surfactant films as in the quasistatic cycles shown in Fig. 5. Native SP-C is very efficient to cooperate with SP-B in lowering surface tension upon minimal compression in the presence of cholesterol, while producing compression-expansion isotherms with very little hysteresis and very low maximum surface tension. On the other side, films containing cholesterol and nonpalmitoylated rSP-C CC reach rapidly 20 mN/m upon compression but do not progress further to lower pressures, presumably because in the absence of palmitoylation the protein is not efficient in preventing relaxation of the fluid cholesterol-containing films upon compression. Interestingly, rSP-C FF is able to mimic the behavior of the native protein to some extent but only in the first cycle. The phenyl rings can probably support some anchoring of SP-C, but not to the same degree as the palmitoyl groups that are able to penetrate deep into the films. It should be noted that dynamic cycling isotherms of films containing rSP-C FF showed a certain variance, in some cases being even more similar to the isotherms of films containing the palmitoylated protein (see Fig. S3 showing four independent experiments).

Figure 6.

Dynamic cycling and SP-B/SP-C cooperation in cholesterol-containing surfactant films. Films formed from DPPC/POPC/POPG (50:25:15, w/w/w) suspensions containing 1% w/w SP-B and no cholesterol (top left) or containing 5% (w/w) cholesterol (right panels) were subjected to dynamic cycling in the absence of SP-C (top), or in the presence of 2% (w/w) of native SP-C (upper center), rSP-C CC (lower center), or rSP-C FF (bottom).The surface-tension-versus-relative-area is plotted for the first, 10th, and 20th cycle of continuous compression-expansion isotherms.

As a complementary control, we also performed cycling experiments with films simultaneously containing SP-B and one of the different forms of SP-C, but in the absence of cholesterol (Fig. S4). Both the quasistatic and the dynamic behavior of lipid films containing SP-B and native palmitoylated SP-C resembled the results shown in Figs. 5 and 6, obtained in the presence of cholesterol, which were characterized by minimal surface tensions close to 0 mN/m attained with low compression rates (≤20%), little compression-expansion hysteresis and low maximum tensions. In the absence of cholesterol, however, we could also observe a different effect of the recombinant versions of SP-C on the behavior of the lipid films during quasistatic and dynamic cycling.

As shown in the four lower panels of Fig. S4, the interfacial films containing recombinant proteins were also able to reach very low surface tensions, just like in the presence of the native protein. Especially in dynamic cycles, though, considerable differences could be observed in terms of hysteresis and maximum surface tensions, which were both significantly impaired in the presence of recombinant SP-C forms compared with the behavior of films containing the palmitoylated native version of SP-C. These results suggest that in films containing the recombinant proteins that lack palmitic chains, and despite the presence of SP-B, some of the material that is excluded during compression is not efficiently respread when cycling is fast.

To discard that the inefficiency of the recombinant SP-C forms to mimic the behavior of native SP-C could be due to the N-terminal dipeptide extension of all the recombinant protein versions studied, we produced a recombinant SP-C bearing phenylalanines and lacking the GP extension (see compared sequences in Table S1). As summarized in the Fig. S5, the behavior of this variant lacking the GP extension was completely analogous to that of the rSP-C FF form so far described. It restores interfacial adsorption of SP-B-containing samples in the presence of cholesterol, and maintains good respreading properties during film expansion, while it was inefficient to restore the ability of the films to produce low enough surface tension upon compression.

To check whether the differences detected in surface behavior between native and recombinant forms of SP-C could be still due to structural differences of the proteins once reconstituted in membranes, we carried out a conformational analysis of the proteins in the two lipid systems studied, by means of far-ultraviolet circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Fig. S6 compares the CD spectra of SP-C and rSP-C reconstituted in DPPC/POPC/POPG membranes in the absence or presence of 5% cholesterol. CD spectra were consistent with a mainly α-helical conformation of the two proteins in the two studied environments, discarding that production/manipulation of the proteins had shifted the typical helical conformation of SP-C toward β-sheet aggregates (25).

Interestingly, the presence of cholesterol slightly increased the negative ellipticity of the CD spectra of the two proteins, which can be indicative of an increase/stabilization of their α-helical content. Determination, from the CD spectra, of the content of the different types of secondary structure (see Table S2) revealed that native SP-C had 58 ± 2% and 61 ± 1% α-helix in the absence and in the presence of cholesterol, respectively, while rSP-C contains 61 ± 3% α-helix in the absence of cholesterol and 70 ± 5% in its presence. Differences in helicity between the two proteins, in the absence or in the presence of cholesterol, are not significant. However, the presence of cholesterol seems to introduce a consistent similar trend toward an increase in helical content in the two proteins, as it was recently revealed for the native protein using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (26).

Discussion

The role of cholesterol in pulmonary surfactant has remained elusive, and is vigorously debated. In native pulmonary surfactant, cholesterol is critical to sustain segregation of fluid-ordered and fluid-disordered phases and it influences phospholipid mobility and dynamics (14) with possible consequences for surfactant film stability. Although surfactant films must be rigid enough to support high surface pressures, they must also be sufficiently dynamic to cope with the continuous compression/expansion cycles that occur during breathing. While the high content in saturated lipids (mainly DPPC) is pivotal for the mechanical stability of pulmonary surfactant, cholesterol could improve the dynamic behavior of the lipid films. In heterothermic animals, the proportion of cholesterol in pulmonary surfactant increases when the body temperature decreases, highlighting its physiological importance (15). Nevertheless, cholesterol is considered detrimental to surfactant function based on in vitro data, where it impairs the surface activity of surfactant films (27). An exacerbated proportion of cholesterol in surfactant has been associated with ARDS (13), a condition with a fatality of 30–40%, and with an incidence of 150,000 cases per year in the US. For these reasons, cholesterol is removed from all clinically used surfactants (12).

Recent data suggest that SP-C could have an important role to sustain surfactant function in the presence of cholesterol (16). In most animals SP-C is dually palmitoylated at cysteine residues 5 and 6. Protein palmitoylation has been reported to promote interaction of some proteins with cholesterol-enriched raftlike domains in membranes (28). We therefore wondered whether palmitoylation could also be essential for SP-C to interact with cholesterol-rich lipid domains and so to promote stability of cholesterol-containing surfactant films under compression/expansion dynamics. Previously, palmitoylation of SP-C had been primarily linked to the structural integrity of mature SP-C (29), but also to a role in maintaining the mechanical stability of surfactant films (9,10). These studies, however, relied on model systems that did not include cholesterol and varied greatly in the sources of SP-C and the methods of analysis.

Our data indicate that, in cholesterol-free systems, palmitoylation of SP-C is not essential to promote interfacial adsorption of phospholipids, an activity strictly required to facilitate formation and reextension of surface active films. These results agree with previous data showing that, under equilibrium conditions, deacylated SP-C is equally active in facilitating the insertion of phospholipids into interfacial films (9,10). In contrast, in the presence of cholesterol, palmitoylated SP-C showed clearly better interfacial adsorption capabilities than the nonpalmitoylated recombinant protein, an activity that could be mimicked by replacing palmitoylated cysteines with phenylalanines. During compression/expansion cycles, the lack of palmitoylation resulted in an increased maximum surface tension and a reduced ability of the films to reach very low surface tensions, particularly in the quasistatic regime. These results illustrate why a synthetic surfactant preparation containing recombinant SP-C as the single protein additive could be efficient enough to be useful in respiratory therapies (30), particularly if using SP-C forms bearing phenylalanines, in lipid mixtures lacking cholesterol.

The differences between native and recombinant SP-C in equilibrium adsorption that were seen in the presence of cholesterol were not observed when SP-B was also present in the surfactant samples (seen in Fig. 4). Therefore, palmitic chains are apparently not essential for SP-C to cooperate with SP-B in promoting interfacial adsorption of cholesterol-containing lipid-protein samples. On the other hand, native palmitoylated SP-C counteracts the deleterious effects of cholesterol in cycling dynamics of SP-B-containing films. In the absence of palmitic chains, however, recombinant SP-C forms are not completely efficient in preventing the negative effects of cholesterol. Still, the recombinant versions of SP-C are able to fulfill some functions in cooperation with SP-B. Fig. 5 shows how both recombinant versions of SP-C can limit maximum surface tensions to values very similar to those obtained for native SP-C, although they are unable to improve minimum surface tensions. We conclude that the reinsertion of phospholipids into the lipid film during expansion that is facilitated by SP-C does not depend on the palmitic chains when SP-B is also present.

A last remarkable feature revealed by our results is that recombinant forms of SP-C, but not the native palmitoylated protein, could somehow affect negatively the activity of SP-B. Incorporation of native SP-C does not essentially affect the behavior of SP-B-containing films subjected to quasistatic or dynamic compression-expansion cycling (compare upper panels in Fig. S5 with the left panel in Figs. 5 and 6). However, incorporation of the two recombinant SP-C forms tested here impairs substantially the compression/expansion dynamics of SP-B-containing films, which behave practically as in the absence of SP-B (compare Fig. S5 with the upper panels in Fig. 3). The design and production of future surfactant preparations that could combine analogs of both SP-B and SP-C will require a detailed study confirming that the analogs of the two proteins do really cooperate and are not actually counteracting under physiologically meaningful dynamic constraints.

Differences in activity of native palmitoylated and nonpalmitoylated recombinant SP-C forms are not due to differences in the conformation of the proteins, as confirmed by CD spectroscopy. Both proteins have a similar α-helical conformation, and they both are similarly influenced by the presence of cholesterol. As it was also determined for native SP-C by using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (26), cholesterol could increase the amount and/or stability of the α-helical conformation, probably as a consequence of a cholesterol-promoted increase in the thickness of membranes. Other data (31) also support the concept that native and recombinant SP-C interact similarly with membranes containing cholesterol, suggesting that the differences observed in this study with respect to surface behavior are only manifested once the lipid-protein complexes are subjected to high lateral pressures during compression of the interface.

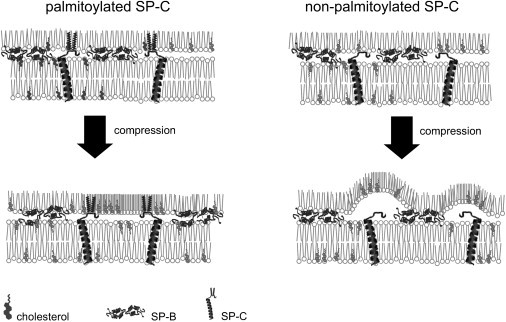

Fig. 7 shows a model that illustrates how palmitoylation could facilitate SP-C-promoted stabilization of compressed states in cholesterol-containing surfactant films. Previous studies have shown that palmitoylation is crucial for SP-C to remain associated with lipid films subjected to high compression (32). At the most compressed states, certain regions of surfactant films likely have properties of a solidlike condensed phase in the absence of cholesterol, or more similar to a liquid-ordered phase in the presence of cholesterol. The partial fluidity of liquid-ordered regions could impart a highly dynamic character (14) particularly favorable to facilitate dynamics of the film upon compression/expansion cycling, but it would make the film more unstable at the high pressures than an actual solid phase.

Figure 7.

Model for the role of palmitoylation of SP-C in surfactant film stability.

We propose that SP-C-promoted association of surfactant bilayers with highly packed liquid-ordered regions would provide additional stability to the multilayered interfacial film at the end of expiration, and that palmitoylation would be required for SP-C to sustain association with ordered phases compressed to their most condensed state, precluding their out-of-plane relaxation (21). In the absence of palmitoylation, SP-C could still associate with bilayers and monolayers, and therefore contribute to promote lipid transfer, but could not maintain association with the maximally compressed states of the interfacial film, which would then become intrinsically unstable and could partially collapse before reaching maximal pressures (minimal tensions). The difference between the effects of palmitoylated and nonpalmitoylated SP-C could be more evident in the presence of cholesterol because, in its absence, the solid character of condensed patches could provide enough stability even in the absence of tight bilayer-monolayer contacts.

Overall, our results suggest that optimization of new clinical surfactants may require the defined combination of proper versions of surfactant proteins. Nonpalmitoylated forms of SP-C produced in bacteria may be useful as a basis to produce relatively simple surfactant preparations, with good surface activity under basic conditions. However, surfactants containing deacylated SP-C may not be efficient enough under more demanding conditions, such as those potentially existing in the airways of patients suffering of ARDS or other pathologies, where an excess of cholesterol may constitute an insuperable challenge.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science (No. BIO2009-09694, No. BFU2009-10442, No. BFU2009-08401, and No. CSD2007-00010), the Community of Madrid (No. S0505/MAT/0283), Complutense University, and the Marie Curie Network (No. CT-04-007931).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Pérez-Gil J. Structure of pulmonary surfactant membranes and films: the role of proteins and lipid-protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1676–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuo Y.Y., Veldhuizen R.A., Possmayer F. Current perspectives in pulmonary surfactant—inhibition, enhancement and evaluation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1947–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallman M., Glumoff V., Rämet M. Surfactant in respiratory distress syndrome and lung injury. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;129:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Possmayer F., Nag K., Schürch S. Surface activity in vitro: role of surfactant proteins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;129:209–220. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almlén A., Stichtenoth G., Curstedt T. Surfactant proteins B and C are both necessary for alveolar stability at end expiration in premature rabbits with respiratory distress syndrome. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1101–1108. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00865.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson J. Structure and properties of surfactant protein C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1408:161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasser S.W., Detmer E.A., Whitsett J.A. Pneumonitis and emphysema in SP-C gene targeted mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14291–14298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schürch S., Qanbar R., Possmayer F. The surface-associated surfactant reservoir in the alveolar lining. Biol. Neonate. 1995;67(Suppl 1):61–76. doi: 10.1159/000244207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafsson M., Palmblad M., Schürch S. Palmitoylation of a pulmonary surfactant protein C analog affects the surface associated lipid reservoir and film stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1466:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qanbar R., Cheng S., Schürch S. Role of the palmitoylation of surfactant-associated protein C in surfactant film formation and stability. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:L572–L580. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonenko Z., Gill S., Amrein M. An elevated level of cholesterol impairs self-assembly of pulmonary surfactant into a functional film. Biophys. J. 2007;93:674–683. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.106310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanco O., Pérez-Gil J. Biochemical and pharmacological differences between preparations of exogenous natural surfactant used to treat Respiratory Distress Syndrome: role of the different components in an efficient pulmonary surfactant. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;568:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markart P., Ruppert C., Guenther A. Patients with ARDS show improvement but not normalization of alveolar surface activity with surfactant treatment: putative role of neutral lipids. Thorax. 2007;62:588–594. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernardino de la Serna J., Orädd G., Perez-Gil J. Segregated phases in pulmonary surfactant membranes do not show coexistence of lipid populations with differentiated dynamic properties. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1381–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orgeig S., Daniels C.B. The roles of cholesterol in pulmonary surfactant: insights from comparative and evolutionary studies. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;129:75–89. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gómez-Gil L., Schürch D., Pérez-Gil J. Pulmonary surfactant protein SP-C counteracts the deleterious effects of cholesterol on the activity of surfactant films under physiologically relevant compression-expansion dynamics. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2736–2745. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pérez-Gil J., Cruz A., Casals C. Solubility of hydrophobic surfactant proteins in organic solvent/water mixtures. Structural studies on SP-B and SP-C in aqueous organic solvents and lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1168:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukovic D., Plasencia I., Mingarro I. Production and characterization of recombinant forms of human pulmonary surfactant protein C (SP-C): structure and surface activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:509–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schürch S., Bachofen H., Possmayer F. A captive bubble method reproduces the in situ behavior of lung surfactant monolayers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;67:2389–2396. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.6.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schürch S., Bachofen H., Green F. Surface properties of rat pulmonary surfactant studied with the captive bubble method: adsorption, hysteresis, stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1103:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90066-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Codd J.R., Schürch S., Orgeig S. Torpor-associated fluctuations in surfactant activity in Gould's wattled bat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1580:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(01)00185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoel W.M., Schürch S., Goerke J. The captive bubble method for the evaluation of pulmonary surfactant: surface tension, area, and volume calculations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1200:281–290. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foot N.J., Orgeig S., Daniels C.B. The evolution of a physiological system: the pulmonary surfactant system in diving mammals. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006;154:118–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Nahmen A., Schenk M., Amrein M. The structure of a model pulmonary surfactant as revealed by scanning force microscopy. Biophys. J. 1997;72:463–469. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szyperski T., Vandenbussche G., Johansson J. Pulmonary surfactant-associated polypeptide C in a mixed organic solvent transforms from a monomeric α-helical state into insoluble β-sheet aggregates. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2533–2540. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez-Gil L., Pérez-Gil J., Goormaghtigh E. Cholesterol modulates the exposure and orientation of pulmonary surfactant protein SP-C in model surfactant membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:1907–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taneva S., Keough K.M. Cholesterol modifies the properties of surface films of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine plus pulmonary surfactant-associated protein B or C spread or adsorbed at the air-water interface. Biochemistry. 1997;36:912–922. doi: 10.1021/bi9623542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resh M.D. Membrane targeting of lipid modified signal transduction proteins. Subcell. Biochem. 2004;37:217–232. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5806-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustafsson M., Griffiths W.J., Johansson J. The palmitoyl groups of lung surfactant protein C reduce unfolding into a fibrillogenic intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:937–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawgood S., Ogawa A., Benson B. Lung function in premature rabbits treated with recombinant human surfactant protein-C. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:484–490. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumgart F., Loura L., Perez-Gil J. Pulmonary surfactant protein C reduces the size of liquid ordered domains in a ternary membrane model system. Biophys. J. 2009;(Abstracts Issue):608a–609a. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi X., Flach C.R., Mendelsohn R. Secondary structure and lipid interactions of the N-terminal segment of pulmonary surfactant SP-C in Langmuir films: IR reflection-absorption spectroscopy and surface pressure studies. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8385–8395. doi: 10.1021/bi020129g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.