Abstract

The 27-residue membrane-spanning domain (MSD) of the HIV-1 glycoprotein gp41 bears conserved sequence elements crucial to the biological function of the virus, in particular a conserved GXXXG motif and a midspan arginine. However, structure-based explanations for the roles of these and other MSD features remain unclear. Using molecular dynamics and metadynamics calculations of an all-atom, explicit solvent, and membrane-anchored model, we study the conformational variability of the HIV-1 gp41 MSD. We find that the MSD peptide assumes a stable tilted α-helical conformation in the membrane. However, when the side chain of the midspan Arg 694 “snorkels” to the outer leaflet of the viral membrane, the MSD assumes a metastable conformation where the highly-conserved N-terminal core (between Lys681 and Arg694 and containing the GXXXG motif) unfolds. In contrast, when the Arg694 side chain snorkels to the inner leaflet, the MSD peptide assumes a metastable conformation consistent with experimental observations where the peptide kinks at Phe697 to facilitate Arg694 snorkeling. Both of these models suggest specific ways that gp41 may destabilize viral membrane, priming the virus for fusion with a target cell.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry into the target cells is mediated by trimeric complexes or spikes, comprised of glycoprotein heterodimers. Each heterodimer is a noncovalently linked complex of receptor-targeting gp120 and membrane-anchoring gp41. Beginning at its N-terminus, gp41 is comprised of a glycine-rich fusion peptide, the so-called N- and C-terminal heptad repeats (NHR and CHR, respectively), a membrane-proximal external region, a membrane-spanning domain (MSD), and a long cytoplasmic tail that extends into the endoplasmic side of the viral lipid bilayer envelope. When spike-associated gp120 binds to its target CD4 receptor, it undergoes conformational changes that:

-

1.

Decrypt a binding site for CCR5/CXCR4 receptors.

-

2.

Initiate a cascade of conformational changes in gp41 (1–7).

These changes are thought to include insertion of previously spike-sequestered fusion peptides into the target cell membrane and eventual refolding of the NHR/CHRs to form a so-called six-helix bundle which pulls the viral and cell membranes together in preparation for fusion (8). Although this pull-model of membrane fusion is theoretically appealing, it does not address the experimentally observed behavior of certain gp41 mutants, especially those that strengthen the interaction of gp41's MSD with the viral membrane while compromising infectivity (9). We speculate that a major functional role of gp41 is to destabilize the viral membrane as a necessary part of the fusion mechanism.

The MSD is a highly conserved region of gp41, spanning 27 residues from Lys681 to Arg707 and contains a midspan charged residue Arg694 (9), a common feature of lentiviral MSDs (Fig. 1) (10,11). For the entire MSD to span the viral membrane, Arg694 localizes to the hydrophobic core, which is energetically unfavorable compared to being solvated by water. However, residues such as arginine, when required by sequence to be inside a lipid membrane, snorkel; i.e., the charged end groups of the side chains localize to the hydrophilic headgroups of one membrane leaflet (12). The MSD also contains a GXXXG motif between residues 688 and 692. Although GXXXG motifs are thought to be involved in interhelical interactions (13,14), the loss of these residues does not affect the trimerization of the Env monomers required during transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus (9). However, loss of Arg694, the GXXXG motif, or the charged residues Lys681 and Arg705 affect membrane fusion and viral infectivity (9,11,15–17).

Figure 1.

Free energy profiles of MSD in a lipid membrane with Arg694 snorkeling toward exoplasmic headgroups sampled during 260-ns metadynamics (red) and Arg694 snorkeling toward endoplasmic headgroups sampled during 140-ns metadynamics run (blue) and schematic illustration of MSD with basic charged residues in blue and polar residues in green. Hydrophobic residues are shown in silver and the Arg694 side chain is shown in exoplasmic (red) and endoplasmic (blue) snorkeling positions.

The purpose of this study is to understand the structure and orientation of MSD in membrane and water environments and the effects of MSD conformation on the viral membrane structure to provide clues toward an explanation of the functional roles of conserved MSD features. Recent simulation studies suggested that the MSD assumes an α-helical conformation in a lipid membrane (18). However, classical molecular dynamics simulation is likely insufficient for sampling all relevant protein conformations due to computational limitations. We therefore used metadynamics to accelerate conformational sampling of MSD, and we predict conformations in both membrane-spanning and water-solvated states lowest in free energy. In particular, we demonstrate the effects of snorkel direction of the Arg694 side chain on water penetration to the membrane core and local membrane thinning.

Methods

General

All simulations were performed using NAMD 2.7b1 with the CHARMM force field and explicit TIP3P water (19–21). VMD 1.8.7 was used for visualization and preparation of the simulation systems (22). All production runs were performed in the NVT ensemble unless explicitly specified using a Langevin thermostat at a temperature of 310 K, with a coupling constant of 5 ps−1.

Gp41 MSD model

HIV-1 gp41 MSD (681-KLFIMIVGGLVGLRIVFAVLSIVNRVR-707) is a 27-amino-acid peptide thought to span the bilayer as an α-helix based on sequence (9,15,18). We modeled gp41 MSD from a 27-amino-acid helical subdomain of the HIV-1 Vpu protein. The side-chain atoms of the Vpu subdomain were deleted and replaced with those of the HIV-1 gp41 MSD. The obtained MSD structure was then solvated with 14,647 water molecules, neutralized, and brought to an ionic strength of 0.1 M by adding Na+ and Cl− ions and was volume-equilibrated for 100 ps in the NPT ensemble. This system was then equilibrated for a total of 20 ns in the NVT ensemble.

Gp41-membrane model

We used steered molecular dynamics (SMD) to insert water-equilibrated α-helical MSD into solvated lipid bilayers comprised of 50 mol% dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC)/cholesterol (23–25). Two MSD-membrane simulation systems were prepared (Fig. S1, A and B, in the Supporting Material):

-

1.

MSD inserted with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups.

-

2.

MSD inserted with Arg694 snorkeling toward the endoplasmic headgroups.

The exoplasmic (N-terminal) and endoplasmic (C-terminal) sides of the membrane are only based on the orientation of the MSD peptide in the bilayer and the lipid and solution composition of the leaflets are similar.

The CHARMM-GUI membrane builder was used to generate initial bilayer structures containing 512 lipid molecules (26). An initial MSD-membrane system was prepared by placing MSD 35 Å above the lipid bilayer and the system was fully solvated by adding explicit TIP3P water molecules. The simulation box measured 105 Å × 98 Å × 127 Å and contained a total of 141,642 atoms with 512 lipid molecules, 29,561 water molecules for complete solvation of the bilayer and MSD, and 280 Na+ and Cl− ions. The system was then equilibrated in the NPT ensemble for 6 ns. After equilibration, the MSD peptide was inserted into the lipid bilayer using constant velocity SMD. To obtain the exoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling model, we used the center-of-mass of Arg707 as the SMD atom and steered the peptide in the membrane from the exoplasmic side of the bilayer with Arg694 interacting with the water molecules and lipid headgroups toward the exoplasmic leaflet. Similarly, to obtain the endoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling model we used the center-of-mass of Lys681 as the SMD atom and inserted the peptide from the endoplasmic side of the bilayer. For both models, we used a steering velocity of 10 Å/ns and the lipid headgroups were restrained in the z direction to prevent bilayer distortion. Insertion of MSD into the membrane to obtain the exoplasmic snorkeling model resulted in slight unfolding of the helix near 696–698 and 704–707. Therefore, in the endoplasmic snorkeling model, the MSD secondary structure was restrained during insertion. However, both the models showed a good structural conservation after a 20-ns MD equilibration (Fig. S1 C).

After MSD insertion, the simulation system was cropped by removing the excess water required to solvate MSD before insertion. Moreover, the lipid bilayer was also cropped to reduce the system size while maintaining at least twice the theoretical length of MSD (40 Å) in the lateral dimensions. The simulation boxes measured 80 Å × 84 Å × 80 Å and 85 Å × 81 Å × 77 Å and the total number of atoms were 58,524 and 58,185 for the exoplasmic and endoplasmic snorkeling models, respectively. The final gp41-membrane models contained ∼320 lipid molecules and a 32:1 water/lipid ratio to ensure complete solvation. The systems were then neutralized and brought to an ionic strength of 0.1 M by adding Na+ and Cl− ions and were equilibrated in the NVT ensemble for at least 5 ns before the metadynamics calculations.

Metadynamics

In metadynamics, system forces in the MD simulation are augmented by those arising from a history-dependent potential, which induces uniform sampling (i.e., overcomes free energy barriers) along a specified collective variable (CV) (27–32). Following Laio and co-workers, we used the external potential

| (1) |

where ξi is the value of the CV, ξi(t′) is the value of ξi at time t′ from the atomic coordinates, W is the Gaussian height, δξ is the Gaussian width, and t′ values are the number of MD steps between every Gaussian deposited. The metadynamics potential, when converged, also provides a good estimate of the free energy as a function of the CV. Metadynamics in various forms has recently been applied for efficient conformational sampling and developing free energy profiles in various protein systems (32–37).

For this study, the root mean-squared displacement of the backbone (C, Cα, N, O) atoms with respect to those in a perfect α-helix (RMSDα) was chosen as the CV. For all metadynamics simulations, we used kcal/mol, δξ = 0.01 Å, and deposited a new Gaussian every 1 ps. A low RMSDα on the free energy profile indicates a helical conformation, whereas kinks and unfolding of the peptide occur at relatively larger RMSDα. For the MSD-membrane models, the arithmetic average of the free energy profiles in two 10-ns intervals after a certain filling time (tf) were compared to judge the convergence of metadynamics calculations (Fig. S8 and Fig. S9). The filling time tf = 240 ns for the exoplasmic model and tf = 120 ns for the endoplasmic model, after which the calculation sampled the CV range diffusively. For the MSD solvated in water, convergence of the free energy profiles was tested by performing two 120-ns metadynamics runs with the MSD solvated in water starting from two different initial conformations (details are provided in the Supporting Material text). The free energy profiles between CV space of 0 and 10 Å were considered converged, and the RMSDα CV extensively sampled conformations within this region during both the MSD-membrane and MSD-water simulations. Metadynamics calculations at RMSDα higher than 10 Å resulted in unfolding of the MSD peptide and are not thoroughly sampled by the RMSDα CV with respect to a perfect α-helix, and therefore are not reported in this work.

Results

Effects of Arg694 snorkel direction on MSD conformational ensembles

A single 260-ns metadynamics simulation resulted in uniform exploration of CV-space between 0–13 Å RMSDα, when initiated from a helical conformation in which the Arg694 side chain snorkels toward the exoplasmic headgroups. The averaged free energy profile for the last 10 ns computed using metadynamics is shown in Fig. 1. Conformations with RMSDα between 1 and 2 Å display the lowest free energy. The RMSDα visited helical and nonhelical states several times through out the 260-ns metadynamics calculation (Fig. S2).

The most stable conformation in this model is a complete α-helical conformation with Arg694 side-chain snorkeling to interact with the water molecules and lipid headgroups toward the exoplasmic leaflet. In this conformation, the peptide tilts with respect to the membrane-normal to facilitate Arg694 snorkeling while preventing water molecules from interacting with the hydrophobic residues between 681 and 692—thereby stabilizing the α-helix. However, the proximity of Arg694 to the glycines in the GXXXG motif results in water molecules interacting with Gly688, Gly689, and Gly692. Thermal fluctuations result in opening and closing of the backbone hydrogen bonds in the α-helix, and water molecules competing for the hydrogen bonds destabilize the α-helical structure. Furthermore, the propensity of hydrophobic residues to localize in the membrane core results in peptide bending at Val691. However, water interactions with glycines result in the MSD eventually kinking at Gly692 and also unfolding of the GXXXG motif, with the hydrophobic Leu690 and Val691 buried in the membrane core and Gly688, Gly689, and Gly692 interacting with water. The free energy profile suggests metastable kinked conformations with RMSDα between 4 and 6 Å.

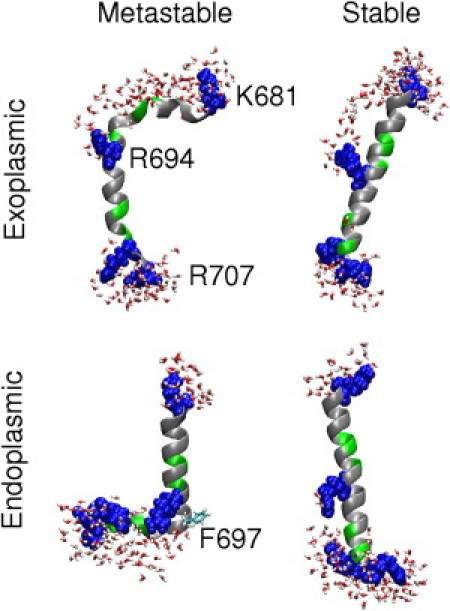

The metastable state has the Arg694 side chain interacting with the exoplasmic headgroups and water molecules, with the MSD kinked at Gly692 and unfolding of the GXXXG motif (Fig. 2). The rest of the peptide between residues 694 and 702 retains an α-helical structure in this conformation. However, the C-terminal residues from 703 to 707 unfold to facilitate Arg694 snorkeling and thereby also the loss of a helical turn at the C-terminus. In addition, peptide conformations with a complete helical structure (but kinked at Arg694) were sampled at RMSDα of 4–8 Å.

Figure 2.

Representation of stable and metastable conformations of MSD in a lipid bilayer with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic and endoplasmic headgroups.

Unfolding of the subdomain between residues 681 and 694 is the combined result of hydrophobic localization in the membrane core, Lys681 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic lipid headgroups, and the presence of water molecules destabilizing the helical structure. However, these conformations had a relatively high RMSDα (8–10 Å) and, as can be seen from the free energy profile, are relatively unstable. Finally, we note that the Arg694 side chain remained in interaction with the exoplasmic headgroups throughout the calculation.

We conducted a second metadynamics calculation initiated from an α-helix with the Arg694 side-chain snorkeling toward the endoplasmic headgroups. During this run, metadynamics sampled the CV space between 0 and 15 Å RMSDα again uniformly and the simulation was stopped at 140 ns when the peptide completely unfolded (Fig. 1). The two predominant conformations in this model are

-

1.

A completely helical conformation, with RMSDα <2 Å and the axis of the α-helix tilting with respect to the membrane-normal to facilitate snorkeling of the Arg694 side chain.

-

2.

A kinked helix, RMSDα 4–6 Å, with the kink at Phe697 and residues 681–697 spanning the bilayer along with the snorkeling side chains of Lys681 and Arg694 (Fig. 2).

Of these, the tilted α-helical conformation between RMSDα 0 to 2 Å is the more stable structure. In this conformation, Arg694 snorkels toward the endoplasmic headgroups and interacts with water molecules penetrating the lipid bilayer. Arg705 positioned on the same side of the α-helix, near the C-terminus of the MSD, assists in α-helix tilting by interacting with water molecules and lipid headgroups at the membrane-water interface. Moreover, Arg705 also interacts with water molecules penetrating the membrane core toward Arg694. Interaction of Arg705 with both the molecules at the membrane-water interface and those water molecules in the membrane core that have a paddle motion was also observed in the 20-ns MD simulation. Therefore, in a completely α-helical conformation the presence of a charged residue with a relatively large side chain assists in snorkeling of Arg694 by inducing helix tilt and also acting as a mediator for water molecule penetration into the membrane core.

Furthermore, with two long side chains of Arg694 and Arg705 interacting with the water molecules in the membrane core, the backbone hydrogen bonds between the residues 694 and 705 were shielded from competition from water. A tilted, completely α-helical MSD conformation was also favorable to the two charged residues, Lys681 and Arg707, on either terminus of the MSD. The long side chains of lysine and arginine are also predominantly hydrophobic except for the charged moieties at the end. We observed that in a tilted α-helix the N-terminus of the MSD was in the hydrophobic membrane environment while the tip of the side-chain snorkels and interacts with the lipid headgroups and water. Similarly, the tilt also pulled Arg707 relatively further into the membrane core, where it could then snorkel and interact with molecules at the membrane-water interface.

The set of conformations that were extensively sampled with ∼4 Å RMSDα were very similar to the hypothesized snorkeling model proposed by Yue et al. (15) (Fig. 2). In this set, the presence of water molecules near the C-terminal residues of the MSD, especially when Arg705 interacts with molecules at the membrane-water interface, results in destabilization of the helix with loss of a hydrogen bond between Phe697 and Ser701. This results in the MSD α-helix bending at Phe697, whereas the rest of the subdomain from 698 to 707 maintains an α-helical conformation. Additionally, the hydrogen bond between Arg694 and Ala698 was maintained even after helix bending. The partitioning of the charged groups toward the membrane-water interface and the hydrophobic groups toward the membrane core assists in maintaining the α-helical conformation by protecting vulnerable backbone hydrogen bonds from attack by water. Residues 681–697 spanned the bilayer in this model with the two long side chains of Lys681 and Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic and endoplasmic headgroups, respectively. These residues maintained a helical structure with the hydrophobic part of the Arg694 side chain shielding the hydrogen bonds between residues 694 and 697 from water molecules in the membrane core. Although these conformations were sampled extensively by metadynamics, the final free energy profile suggests that these conformations are metastable.

As seen in the case of exoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling, metadynamics sampled various unstable and short-lived conformations during endoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling simulation. However, most of these conformations retained the α-helical structure between residues 681 and 697. The presence of lipid headgroups and water molecules at the membrane water interface resulted in destabilization of the helical subdomain between 698 and 707. Conformations with a completely unfolded C-terminal subdomain were also observed. During this run, we also observed a completely unfolded MSD peptide. In these conformations, the C-terminal charged residues and water molecules associated with these residues entered deep into the lipid bilayer core, resulting in the interaction with GXXXG motif and destabilization of the backbone hydrogen bonds.

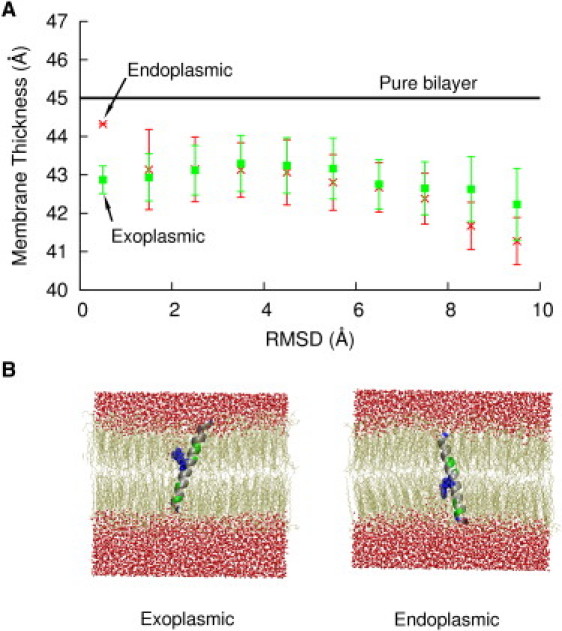

Effects of MSD conformation on membrane thickness

In Fig. 3 A, we show a plot of membrane thickness within 20 Å of the MSD for both the models versus RMSDα. The average bilayer thickness of DPPC-cholesterol (50 mol%) was observed to be 45 Å (blue). Average membrane thickness for both the exoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling model and endoplasmic Arg694 snorkeling model was found to be similar except for RMSDα between 0 and 1 Å. However, membrane thickness for both the models was found to be consistently lower than the pure DPPC-cholesterol bilayer thickness. Exoplasmic snorkeling Arg694 resulted in a localized membrane defect in the upper leaflet whereas endoplasmic snorkeling of Arg694 results in a localized membrane defect in the lower leaflet due to water penetration and lipid headgroups interacting with Arg694. This condition is true for both the tilted completely α-helical conformations that places Arg694 near the center of the bilayer and the metastable kinked conformations in which the membrane spanning subdomains are relatively short. The stable conformations of MSD in both the exoplasmic and endoplasmic snorkeling models in a lipid membrane are shown in Fig. 3 B. For conformations with higher RMSDα in both the models, unfolding of the peptide resulted in charged groups at the termini burying themselves in the hydrophobic core of the bilayer. These conformations resulted in significant water penetration into the membrane.

Figure 3.

(A) Lipid bilayer thickness within 20 Å of MSD as a function of the RMSDα of the MSD conformations. Lipid bilayer thickness for the model with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups (green) is higher than the one toward endoplasmic headgroups (red). The blue line indicates average thickness of the bilayer without MSD. (B) Stable conformations of gp41 MSD in membrane with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic and endoplasmic leaflets.

The gp41 MSD conformational ensemble in pure water

Because water seems to play an important role in the structure of MSD in a membrane, we tested the stability of the α-helical structure of gp41 MSD solvated in water using both molecular dynamics and metadynamics. The RMSDα evolution from a 20 ns MD is shown in Fig. S3. These data suggest a stable conformation of the peptide between RMSDα 5 and 6 Å. However, after 5 ns the MSD assumes a conformation with a higher RMSDα between 7 and 9 Å. Similar behavior was observed after ∼18 ns of MD simulation for the final 2 ns. The α-helical structure was observed to be highly unstable and therefore the MSD immediately kinked within 1 ns at Val691 during the MD run.

This kink is a result of water molecules interacting with the glycine residues and destabilizing the backbone hydrogen bonds while the peptide minimizes the exposure of hydrophobic surface area to water. However, the hydrogen bond between Arg694 and Leu690 was intact even after helix bending. Although the GXXXG motif unfolded to facilitate Gly interactions with water molecules, the rest of the MSD remained helical. The bulky arginine side chains and the phenylalanine side chain, along with the kink, minimize the protein backbone atom interactions with water molecules between residues 692 and 707. The two unstable high-RMSDα structures occur due to the occasional breaking of intrahelical hydrogen bonds between Leu690-Arg694 and Arg694-Ala698. This results in a looplike conformation with RMSDα between 7 and 9 Å. However, a 20-ns MD run is probably insufficient to unfold a helical peptide and sample all relevant conformations. Therefore, two 120-ns metadynamics trajectories were started from different conformations of the peptide randomly selected from the initial MD run, one from an α-helical structure and another from the kinked structure. As with the membrane simulations, RMSDα was the CV.

The MSD peptide assumes a larger number of conformations during these simulations than for those in the membrane. The CV trace during the course of the simulation suggests a thorough sampling of CV space. The free energy profiles from the two runs and the average are presented in Fig. S6. This free energy profile suggests a very stable conformation that has a single kink at the GXXXG motif between 4 and 6 Å RMSDα. The free energy profile also shows that the conformations between 8 and 10 Å RMSDα, although metastable, can be accessed only by overcoming a few kcal/mol free energy barrier. These results support the conformations observed during our initial MD run as in a stable kinked helix at the GXXXG motif and a metastable structure with a second kink at Phe697. Furthermore, the free energy profile also suggests a metastable α-helical structure in water. These results indicate that the residues C-terminal to Arg694 can form a stable α-helical structure even in water and that the residues N-terminal to Arg694 kink at the GXXXG motif as was observed during our membrane simulations with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups. However, it should be noted that with water as solvent and the polar residues accessible, most of the helical structure remained intact, despite the kink, without the degree of unfolding observed in the membrane.

Discussion

In our model with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups, the free energy profile suggested a stable, completely α-helical conformation. To maintain the α-helical conformation, the MSD peptide tilts to facilitate Arg694 snorkeling while preventing water molecules from interacting with the hydrophobic residues. A metastable conformation kinked at Gly692 with an unfolded GXXXG motif was also observed with RMSDα between 4 and 6 Å. This is likely because an α-helical MSD with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups resulted in water molecules in the proximity of the glycines, which then can attack backbone hydrogen bonds involving glycines. This model requires that the MSD subdomain between residues 694 and 707 anchor the spike to the viral membrane in the metastable state. However, recent experimental results based on truncation mutants suggested that addition of just three residues C-terminal to residue 694, up to Phe697, is enough to stably anchor the Env glycoprotein in the membrane (15,16). Therefore, we believe that a MSD model with Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups is improbable in the native spike, although it should not be discounted that these conformations could still play a role in disruption of the viral membrane.

The free energy profile for the model with Arg694 snorkeling toward the endoplasmic headgroups also suggested that the completely α-helical conformation is the most stable conformation. The possibility of the α-helix to tilt and Lys681 and Arg694 to snorkel toward either leaflet's headgroups along with the observed shielding of the backbone hydrogen bonds likely resulted in this stable conformation. A similar phenomenon of shielding of backbone hydrogen bonds (thereby stabilizing the α-helical structure by the arginine side chain) was previously observed in alanine-rich peptides (38). This conformation is consistent with results from truncation studies that show that addition of residues C-terminal to Arg694 increase surface expression by better anchoring of the peptide with increasing number of residues in the α-helix (15). Although this conformation explains the importance of the length of the subdomain between 694 and 707 for the incorporation of the spike and the role of Arg705 in destabilization of viral membrane (and therefore its fusion), it was important as well that this simulation predicted the experimentally hypothesized snorkeling model of the MSD (15) to be metastable. We also observed that the MSD peptide from Lys681 to Phe697 is enough to span the lipid bilayer and anchor the MSD.

Both the Arg694 snorkeling models showed a consistent thinning of the lipid membrane due to water penetration and lipid headgroups interacting with Arg694. Cryo-electron tomographic images of HIV-1 Env spike show an obvious decrease in membrane thickness in the lower leaflet of the bilayer (39), leading us to speculate that Arg694 snorkels toward the endoplasmic headgroups in the native spike.

Based on these observations, we hypothesize that the MSD exists in the metastable kinked snorkeling model in the native spike. Conformational changes in the gp41 ectodomain during the formation of the prefusion intermediate perhaps result in the MSD assuming a tilted, completely α-helical conformation. A tilted α-helix, continuous from Lys681 to Arg707, further assists the penetration of water into the membrane core to interact with Arg694. The GXXXG motif, although insignificant for the incorporation of the native spike (9), is perhaps important to induce interhelical interactions and in maintaining gp41 MSD trimers during these conformational changes (13,14).

Conclusions

We sampled various conformations of the HIV-1 gp41 MSD in a cholesterol-rich lipid bilayer based on two starting models with:

-

1.

Arg694 snorkeling toward the exoplasmic headgroups.

-

2.

Arg694 snorkeling toward the endoplasmic headgroups, using all-atom metadynamics calculations.

Based on our observations and previous experimental results, we hypothesize that the MSD assumes a conformation with the midspan Arg694 snorkeling toward the endoplasmic headgroups in the native spike. Furthermore, there are two conformations—a stable tilted α-helical conformation and a metastable kinked snorkeling conformation—that the MSD likely can shuttle between, during conformational changes of the gp41 ectodomain. It was also observed that the MSD residues from Lys681 to Phe697 are enough to span the bilayer and effectively anchor gp41, consistent with experimental observations. MSD with Arg694 snorkeling toward endoplasmic headgroups also resulted in significant thinning of the membrane. Moreover, we also sampled conformations of MSD in water and reasoned that although the MSD assumes a stable kinked structure in water, it can shuttle among the stable conformation and several metastable conformations.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (grant No. R01 AI-084117-01) and the National Science Foundation (grant No. DMR-0427643) is acknowledged. This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources under grant No. TG-MCB070073N.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Eckert D.M., Kim P.S. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt R., Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen B., Vogan E.M., Harrison S.C. Determining the structure of an unliganded and fully glycosylated SIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Structure. 2005;13:197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen B., Vogan E.M., Harrison S.C. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss C.D., Carol D. HIV-1 gp41: mediator of fusion and target for inhibition. AIDS Rev. 2003;5:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray N., Doms R.W. HIV-1 coreceptors and their inhibitors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;303:97–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-33397-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markovic I., Clouse K.A. Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 entry and fusion: revisiting current targets and considering new options for therapeutic intervention. Curr. HIV Res. 2004;2:223–234. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo S.A., Finnegan C.M., Blumenthal R. The HIV Env-mediated fusion reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1614:36–50. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shang L., Yue L., Hunter E. Role of the membrane-spanning domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein in cell-cell fusion and virus infection. J. Virol. 2008;82:5417–5428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02666-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonigo P., Alizon M., Wain-Hobson S. Nucleotide sequence of the Visna lentivirus: relationship to the AIDS virus. Cell. 1985;42:369–382. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helseth E., Olshevsky U., Sodroski J. Changes in the transmembrane region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 envelope glycoprotein affect membrane fusion. J. Virol. 1990;64:6314–6318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6314-6318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorairaj S., Allen T.W. On the thermodynamic stability of a charged arginine side chain in a transmembrane helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4943–4948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610470104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senes A., Gerstein M., Engelman D.M. Statistical analysis of amino acid patterns in transmembrane helices: the GxxxG motif occurs frequently and in association with β-branched residues at neighboring positions. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:921–936. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russ W.P., Engelman D.M. The GxxxG motif: a framework for transmembrane helix-helix association. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:911–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue L., Shang L., Hunter E. Truncation of the membrane-spanning domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein defines elements required for fusion, incorporation, and infectivity. J. Virol. 2009;83:11588–11598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00914-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens R.J., Burke C., Rose J.K. Mutations in the membrane-spanning domain of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein that affect fusion activity. J. Virol. 1994;68:570–574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.570-574.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyauchi K., Komano J., Matsuda Z. Role of the specific amino acid sequence of the membrane-spanning domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 2005;79:4720–4729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4720-4729.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J.H., Hartley T.L., Engelman D.M. Molecular dynamics studies of the transmembrane domain of gp41 from HIV-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:1804–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKerell A., Bashford D., Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackerell A.D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C.L., 3rd Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brügger B., Glass B., Kräusslich H.G. The HIV lipidome: a raft with an unusual composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell S.M., Crowe S.M., Mak J. Virion-associated cholesterol is critical for the maintenance of HIV-1 structure and infectivity. AIDS. 2002;16:2253–2261. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyader M., Kiyokawa E., Trono D. Role for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 membrane cholesterol in viral internalization. J. Virol. 2002;76:10356–10364. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10356-10364.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jo S., Lim J.B., Im W. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for mixed bilayers and its application to yeast membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laio A., Parrinello M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12562–12566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iannuzzi M., Laio A., Parrinello M. Efficient exploration of reactive potential energy surfaces using Carr-Parrinello molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:238302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.238302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laio A., Gervasio F. Metadynamics: a method to simulate rare events and reconstruct the free energy in biophysics, chemistry and material science. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2008;71:126601. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henin J., Fiorin G., Klein M.L. Exploring multidimensional free energy landscapes using time-dependent biases on collective variables. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:35. doi: 10.1021/ct9004432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crespo Y., Marinelli F., Laio A. Metadynamics convergence law in a multidimensional system. Phys. Rev. E. 2010;81:055701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.055701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinelli F., Pietrucci F., Piana S. A kinetic model of Trp-cage folding from multiple biased molecular dynamics simulations. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaendtner J., Branduardi D., Voth G.A. Nucleotide-dependent conformational states of actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12723–12728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camilloni C., Provasi D., Broglia R.A. Exploring the protein G helix free-energy surface by solute tempering metadynamics. Proteins. 2008;71:1647–1654. doi: 10.1002/prot.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Parrinello M. The unfolded ensemble and folding mechanism of the C-terminal GB1 β-hairpin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13938–13944. doi: 10.1021/ja803652f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domene C., Klein M., Parrinello M. Conformational changes and gating at the selectivity filter of potassium channels. JACS. 2008;138:9874. doi: 10.1021/ja801792g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piana S., Laio A., Martins J. Predicting the effect of a point mutation on a protein fold: the villin and advillin headpieces and their Pro62Ala mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García A.E., Sanbonmatsu K.Y. Alpha-helical stabilization by side chain shielding of backbone hydrogen bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2782–2787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042496899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J., Bartesaghi A., Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.