Abstract

Electrical activity in pancreatic β-cells plays a pivotal role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by coupling metabolism to calcium-triggered exocytosis. Mathematical models based on rodent data have helped in understanding the mechanisms underlying the electrophysiological patterns observed in laboratory animals. However, human β-cells differ in several aspects, and in particular in their electrophysiological characteristics, from rodent β-cells. Hence, from a clinical perspective and to obtain insight into the defects in insulin secretion relevant for diabetes mellitus, it is important to study human β-cells. This work presents the first mathematical model of electrical activity based entirely on published ion channel characteristics of human β-cells. The model reproduces satisfactorily a series of experimentally observed patterns in human β-cells, such as spiking and rapid bursting electrical activity, and their response to a range of ion channel antagonists. The possibility of Human Ether-a-Go-Go-related- and leak channels as drug targets for diabetes treatment is discussed based on model results.

Introduction

In response to raised blood glucose levels, insulin is secreted from the pancreatic β-cells. Metabolism of the sugar leads to increased ATP/ADP ratio, closure of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (K(ATP) channels), and electrical activity, which activates voltage-gated calcium channels. The resulting increase in intracellular calcium evokes insulin release through Ca2+-dependent exocytosis. This pathway of insulin secretion is well studied in rodents, and is also operating in humans (1–3).

The central role of electrical activity is highlighted by the excellent correlation between the fraction of time with electrical activity and insulin secretion (4). The plasma membrane potential in rodents shows complex bursting electrical activity with active phases where action potentials appear from a depolarized plateau, interspaced by silent, hyperpolarized phases (5,6). Mathematical modeling of electrical activity has, for nearly 30 years, accompanied the experimental investigations of the mechanisms underlying bursting electrical activity, starting with the ground-breaking work by Chay and Keizer (7) on which virtually all subsequent models, even the most recent, are based (8–11). Beta-cell models have been used to test, support, and refute biological hypotheses (8,10,12), but frequently restricted to the most studied laboratory animals, in particular the mouse, due to the availability of electrophysiological data.

The interest in insulin secretion and pancreatic β-cells is caused by the central role of impaired insulin secretion in the development of the (human) disease diabetes mellitus. However, human β-cells show important differences to β-cells from mice, for example with respect to the patterns of electrical activity observed, which consist of very fast bursting or spiking in human cells (1,3,13–15), and never the classical slower burst pattern observed in rodents. This difference could be due to the involvement of different ion channels in human β-cells compared to rodents (1,3,14,15) or to differences in islet organization (16,17).

This article presents the first biophysical model of electrical activity based on ion channel characteristics of human β-cells. Special attention has been given to choose model parameters directly from published, high-quality electrophysiological data, mainly from Braun et al. (3), who carefully assured that the investigated islet cells were indeed β-cells, but also from Rosati et al. (18), Herrington et al. (19), and Misler et al. (1). Using published parameters reduced parameter tweaking to a minimum. A similar approach was recently taken for modeling of murine β-cells (11). The presented model includes all voltage-gated currents found in human β-cells, and reproduces a series of experimental data satisfactorily.

Methods

Modeling

Electrical activity is modeled by a Hodgkin-Huxley type model, as has been done for rodent β-cells (7–12,20). Most voltage-gated membrane currents (measured in pA/pF) are modeled based on the results of Braun et al. (3), who carefully assured that investigated human islet cells were β-cells. Human Ether-a-Go-Go-related (HERG) potassium currents in human β-cells were described by Rosati et al. (18) and are modeled accordingly.

The membrane potential V (measured in mV) develops in time (measured in milliseconds) according to

| (1) |

In the following, the modeling of the currents on the right-hand side of Eq. 1 is explained in detail.

The leak current summarizes all currents not modeled explicitly, such as currents mediated by exchangers, pumps, and chloride and nonselective, non-voltage-dependent cation channels, and is modeled as

| (2) |

The ATP-sensitive potassium current is described by

| (3) |

Here, Vleak and VK are the respective Nernst reversal potentials. Misler et al. (1) estimated that at 6 mM glucose, the conductances gleak and gK(ATP) contribute to a similar extent to the total membrane conductance of ∼0.3 nS. With a cell capacitance of ∼10 pF (3), values of gleak = 0.015 nS/pF and gK(ATP) = 0.015 nS/pF are obtained for a glucose-stimulated β-cell. These values are used as default, and can be found with all other default parameter values in Table 1.

Table 1.

Default parameters used unless mentioned otherwise

| Parameter | Ref. | Parameter | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VK | −75 | mV | (3) | VNa | 70 | mV | ∗ | |

| VCa | 65 | mV | ∗ | gK(ATP) | 0.015 | nS/pF | (18) | |

| gleak | 0.015 | nS/pF | (1) | Vleak | −30 | mV | † | |

| gCaT | 0.050 | nS/pF | (3) | τhCaT | 7 | ms | (3) | |

| VmCaT | −40 | mV | (3) | nmCaT | −4 | mV | (3) | |

| VhCaT | −64 | mV | (3) | nhCaT | 8 | mV | (3) | |

| gCaPQ | 0.170 | nS/pF | (3) | nmCaPQ | −10 | mV | (3) | |

| VmCaPQ | −10 | mV | (3) | |||||

| gCaL | 0.140 | nS/pF | (3) | τhCaL | 20 | ms | ∗ | |

| VmCaL | −25 | mV | (3) | nmCaL | −6 | mV | (3) | |

| VhCaL | −42 | mV | (21)† | nhCaL | 6 | mV | (21)† | |

| gNa | 0.400 | nS/pF | (3) | τhNa | 2 | ms | (3) | |

| VmNa | −18 | mV | (3) | nmNa | −5 | mV | (3) | |

| VhNa | −42 | mV | (3) | nhNa | 6 | mV | (3) | |

| gKv | 1.000 | nS/pF | (3) | τmKv,0 | 2 | ms | (3) | |

| VmKv | 0 | mV | (3) | nmKv | −10 | mV | (3) | |

| 0.020 | nS/pA | (3) | τmBK | 2 | ms | (3) | ||

| VmBK | 0 | mV | (3) | nmBK | −10 | mV | (3) | |

| BBK | 20 | pA/pF | (3) | |||||

| gHERG | 0.200 | nS/pF | (18)† | τmHERG | 100 | ms | (26) | |

| VmHERG | −30 | mV | (18) | τhHERG | 50 | ms | (18) | |

| VhCaL | −42 | mV | (18) | nmCaL | −10 | mV | (18) | |

| nhCaL | 17.5 | mV | (18) | |||||

M. Braun, University of Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2010.

Adjusted.

Voltage-gated membrane currents are modeled as

| (4) |

where X denotes the type of channels, the reversal potential of the ion conducted by the channels, while mX describes activation and hX describes inactivation of the channels. As described in the following, some channels are assumed not to inactivate (i.e., hX = 1), some activate instantaneously (mX = mX,∞(V)), but in general, activation (and similarly inactivation, hX) is supposed to follow a first-order equation

| (5) |

where τmX (respectively, τhX) is the time-constant of activation (respectively, inactivation for hX), and mX,∞(V) (respectively, hX,∞(V)) is the steady-state voltage-dependent activation (respectively, inactivation) of the current. The steady-state activation (and inactivation) functions are described with Boltzmann functions,

| (6) |

except for calcium-regulated currents as explained below. For activation functions, the slope parameter nmX is negative, while the corresponding slope parameter nhX is positive for inactivation functions.

As explained in the Supporting Material, Ca2+ and Na+ reversal potentials were assumed different for the experiments used to characterize the currents, compared with the experiments measuring electrical activity (M. Braun, University of Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2010). The overall behavior of the model is not sensitive to this assumption; and spiking and bursting electrical activity can also be observed when VCa and VNa are as in the experiments used to characterize the Ca2+ and Na+ currents. A detailed description of the currents of the model is given in the following.

Voltage-gated calcium channels

Braun et al. (3) found three types (T-, P/Q-, and L-type) of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in human β-cells. The total Ca2+ current activated very rapidly (<1 ms), and no difference in activation kinetics is apparent from the data using various Ca2+ channel blockers ((3), their Fig. 5). It is therefore assumed that all Ca2+ channels activate instantaneously. The activation functions are estimated from the voltage-dependence of peak Ca2+ currents reported by Braun et al. (3), and are given in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material.

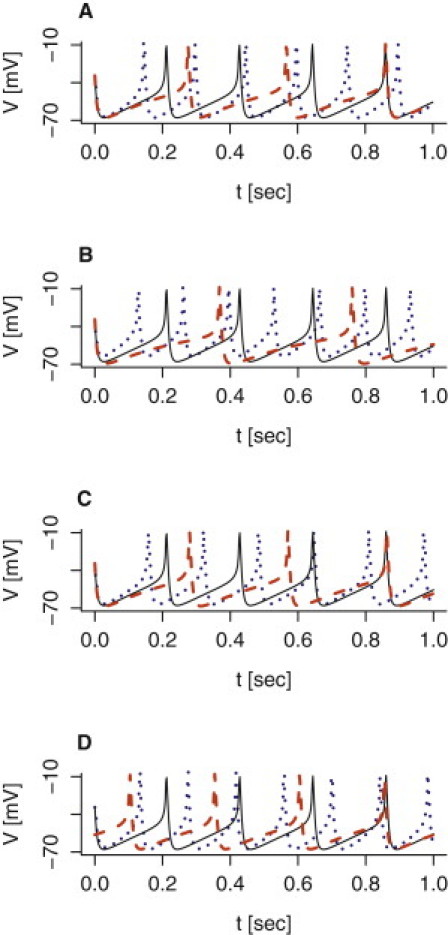

Figure 5.

Model simulations of the effect of potassium channel blockers on electrical activity. (A) The effect of stromatoxin-1 was simulated by setting gKv = 0.5 nS/pF (dashed red), while the effect of iberiotoxin was simulated by setting nS/pA (dotted blue). The simulation with default parameters given in Table 1 is shown (solid black curve). (B) The effect of TEA was simulated by setting gKv = 0.25 nS/pF and nS/pA, resulting in plateau-bursting with default gHERG = 0.2 nS/pF (solid black), or in broad action potentials assuming gHERG = 0.3 nS/pF (dashed red). (C) Adding a modest amount of noise (0.7 Γt, where Γt is a standard Gaussian white-noise process with zero mean and mean square (Γt, Γs) = δ(t – s); see also (39,41)) to Eq. 1 describing the dynamics of the membrane potential V, introduces spikes in the active phase of TEA-induced plateau bursting (black curve in panel B).

The low-voltage activated T-type channels were found to inactivate faster than the L- and P/Q-types ((3), their Fig. 5), and it is therefore assumed to be responsible for the fastest component of total Ca2+ current inactivation with a time constant of τhCaL = 7 ms. Braun et al. (3) found parameters of the Boltzmann function describing steady-state inactivation which are used here without modification.

The high-voltage activated P/Q-type channels are assumed not to inactivate, because they inactivate much more slowly than the other Ca2+ currents and the duration of action potentials (3).

Finally, the high-voltage activated L-type Ca2+ channels inactivate with a time-constant of τhCaT = 20 ms (M. Braun, University of Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2010). The parameters of the inactivation function for L-type Ca2 channels in human β-cells are unknown. However, the inactivation function of the total Ca2+ current has been investigated (21). Inactivation showed a U-shaped voltage dependence with maximal inactivation of ∼50% seen at −10 mV. Because L-type currents make up ∼50% of total peak Ca2+ currents in human β-cells (3), and T-type Ca2+ channels are completely inactivated at −10 mV, while P/Q-type channels do not inactivate substantially (3), it was assumed that the U-shaped inactivation function reflects inactivation of the L-type Ca2+ current with almost complete inactivation at −10 mV. Inactivation of the L-type Ca2+ current was assumed to be Ca2+-dependent and caused mainly by Ca2+ in microdomains below the L-type channels (21,22), which is approximately proportional to the L-type Ca2+ current (23). The amount of inactivation (1 − hCaL,∞ ) was therefore assumed proportional to the activated L-type Ca2+ current mCaL,∞(V)(V − VCa), which yields the expression for the inactivation function

| (7) |

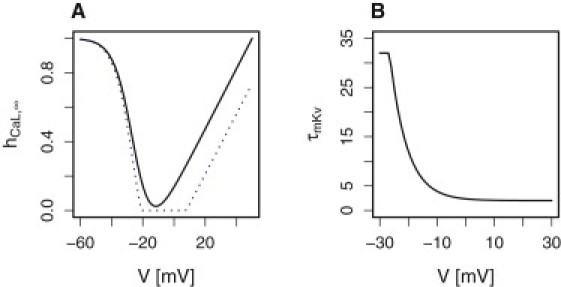

with normalization factor Φ = 57 mV (adjusted) and is shown in Fig. 1 A. (The max-min construction confines hCaL to the interval [0,1]).

Figure 1.

(A) Inactivation function of L-type Ca2+ channels with parameters as in Table 1. Assuming a reversal potential of VCa = 50 mV (21) allowed decent fitting to the inactivation of Ca2+ currents measured by Kelly et al. (21) (solid black) when taking into consideration that L-type currents contribute to ∼50% of the total Ca2+ current in human β-cells (3) as explained in the main text. However, all simulations of electrical activity were done with VCa = 65 mV, which yields stronger inactivation (dotted blue). (B) The voltage-dependent activation time constant of Kv channels τmKv is described by Eq. 8 to reproduce the results of Braun et al. (3). Color figures are available in the online version of this article.

Voltage-gated sodium channels

Based on the rapid kinetics of the Na+ currents (3), the voltage-gated sodium channels were assumed to activate instantaneously, and to inactivate with a time constant of 2 ms. The activation function is estimated from the voltage-dependence of peak Na+ currents reported by Braun et al. (3), and are given in Fig. S2. Braun et al. (3) found parameters of the Boltzmann function describing steady-state inactivation which are used here without modification. Both sets of parameters are in good agreement with estimates by Barnett et al. (15).

Delayed rectifying potassium channels

The delayed rectifying potassium (Kv) channels were assumed to activate on a voltage-dependent timescale (3,19) as shown in Fig. 1 B with the expression

| (8) |

where (as default value) τmKv,0 = 2 ms (3). Note that Herrington et al. (19) found that Kv channels activated more slowly with τmKv,0 ≈ 10 ms. The Kv current was assumed not to inactivate, because of its slow (seconds) inactivation kinetics (3,19).

The activation function is estimated from the voltage-dependence of the Ca2+-resistant peak K+ currents reported by Braun et al. (3), and is given in Fig. S3. The estimated values are in general agreement with the literature (21,19).

Large-conductance BK potassium channels

BK channels show both voltage- and Ca2+ dependence (24). However, because BK- and Ca2+ channels are colocalized and BK channel activation is regulated by local, microdomain Ca2+ below Ca2+ channels (24), a simplification as done for L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation can be done (23). The microdomain Ca2+ concentration is assumed to be proportional to the total Ca2+ current

The steady-state activation function for BK channels is therefore assumed to depend on V only, because it is assumed proportional to the product

where BBK denotes basal, Ca2+-independent, V-dependent activation, and mBK,∞ is a Boltzmann function as in Eq. 6. It is assumed that Ca2+-dependent activation occurs instantaneously, while voltage-dependent activation follows Eq. 5 with time-constant τmBK = 2 ms (3). BK currents were assumed not to inactivate. This was done partly because the inactivation function of BK channels in human β-cells is unknown, and partly because BK currents rapidly repolarize the membrane potential in most simulations, hence deactivation due to repolarization happens faster (∼10 ms) than inactivation at depolarized membrane potentials (∼22 ms (3)).

The BK current is then expressed as

| (9) |

with parameters chosen to reproduce the I-V relationship for the iberiotoxin (a specific BK-channel blocker) sensitive K+ current reported by Braun et al. (3) and shown in Fig. S3 B.

HERG potassium channels

The voltage-gated Human Ether-A-Go-Go-related (HERG) potassium channels are present in human β-cells (18,25). Rosati et al. (18) found parameters of the Boltzmann activation and inactivation functions, which are used here without modification. The time-constant of inactivation was estimated from Rosati et al. (18) to be ∼50 ms, while activation is slower. Based on data from ERG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes (26), the activation time-constant is set to 100 ms. From results in Rosati et al. (18) a conductance of gHERG ∼ 0.5 nS/pF can be calculated. However, gHERG increases with the extracellular K+ concentration (27). Because Rosati et al. (18) used a relatively high extracellular K+ concentration (40 mM) in their experiments, a lower value of gHERG = 0.2 nS/pF was used in the model.

Numerical methods

Simulations were done in XPPAUT (28) by solving the differential equations using the CVODE-solver with standard tolerances and time-step ms. The stochastic simulation, shown later in Fig. 5 C, was done in XPPAUT with the backward Euler method with standard tolerances and ms (29). The computer code is available on http://www.dei.unipd.it/∼pedersen.

Results

Spiking electrical activity

In response to glucose, human β-cells exhibit spiking electrical activity (1,3,18,30). With the parameters estimated from results by Braun et al. (3) and Rosati et al. (18), and a K(ATP)-conductance of 0.015 nS/pF corresponding to 6 mM glucose (1), the model produces action potentials peaking at −8 mV with troughs at −68 mV (Fig. 2). The spike frequency is 4.6 Hz, which is slightly faster than experimental recordings (18,31), but the frequency is sensitive to the assumed properties of the leak current Ileak. For example, raising the leak Nernst potential Vleak increases the spike frequency, while lowering Vleak reduces the frequency (Fig. 2 C). Similarly, raising the leak conductance increases the spike frequency (Fig. 2 B). This is because the membrane potential depolarizes faster, thus reducing the interspike interval. Glucose regulates electrical activity in human β-cells due to its metabolism, which results in increased ATP/ADP ratio and closure of K(ATP) channels (1). With default parameters, the model produces spiking activity when the K(ATP) conductance gK(ATP) is <∼0.019 nS/pF, while the membrane potential is silent and hyperpolarized for larger gK(ATP) values. The spike frequency is inversely related to the K(ATP) conductance (Fig. 2 A). The value for gK(ATP) below which the model produces action potentials can be shifted by modulating the leak current. For example, raising the leak conductance twofold to gleak = 0.030 nS/pF increases the gK(ATP) threshold value to ∼0.027 nS/pF.

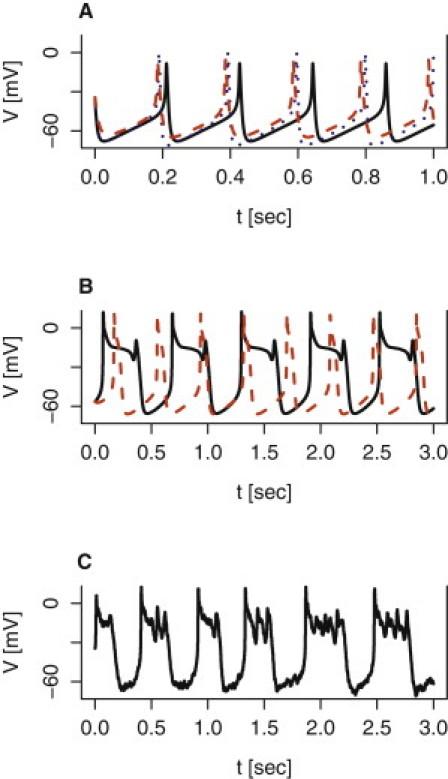

Figure 2.

Model simulations of spiking electrical activity. The simulation with default parameters given in Table 1 is shown by the solid black curve in all panels. (A) The K(ATP) conductance is varied from the default gK(ATP) = 0.015 nS/pF to gK(ATP) = 0.008 nS/pF (dotted blue) and gK(ATP) = 0.018 nS/pF (dashed red). (B) The leak conductance is varied from the default gleak = 0.015 nS/pF to gleak = 0.030 nS/pF (dotted blue) and gleak = 0.010 nS/pF (dashed red). (C) The leak reversal potential is varied from the default Vleak = −30 mV to Vleak = −20 mV (dotted blue) and Vleak = −35 mV (dashed red). (D) Block of HERG channels is simulated by changing HERG-conductance from the default gHERG = 0.2 nS/pF to gHERG = 0 nS/pF (dotted blue). Increasing the time-constant for HERG activation fivefold to τmHERG = 500 ms lowers the spike frequency (dashed red).

Rosati et al. (18) showed that blocking HERG channels in human β-cells increased the glucose-induced spike frequency by ∼30%, in some cases by ∼50%, suggesting an important role for HERG channels in controlling the timing of action potentials. Model simulations with standard parameters support this notion, because blocking the HERG current increases the spike frequency by 52% from 4.6 Hz to 7 Hz (Fig. 2 D). Moreover, the HERG channel activation time-constant plays a role in setting the spike frequency. For example, using τmHERG = 500 ms, a fivefold increase but still in agreement with experiments (26), lowers the spike frequency to 4.0 (Fig. 2 D). Blockage of HERG channels also shifts the gK(ATP) threshold value for electrical activities to ∼0.031 nS/pF.

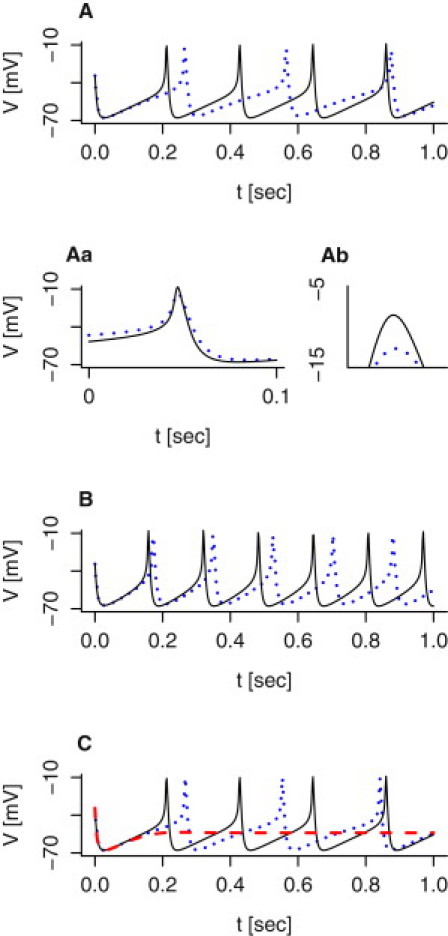

Blocking voltage-dependent Na+ channels in human β-cells with tetrodotoxin (TTX) reduces the action potential amplitude by 10–15 mV, and tends to broaden its duration (3,15,31). These results are captured by the model, though the reduction in peak voltage is slightly less (∼5 mV) than observed experimentally (Fig. 3 Aa). With default parameters, setting gNa = 0 nS/pF increases the interspike interval dramatically (by 44% from 217 ms to 312 ms), but with lower K(ATP) conductance the interspike interval is increased much less, e.g., by 9% from 163 ms to 178 ms with gK(ATP) = 0.008 nS/pF, and the main effect is on the action-potential height (Fig. 3 B). The reduced spike frequency at high gK(ATP) values (reflecting low glucose concentrations), but not at low gK(ATP) values (raised glucose levels), might underlie the fact that TTX reduces insulin secretion less at high than at low glucose concentrations (3,15). The model also reproduces (Fig. 3 C) the facts that a T-type Ca2+ channel antagonist reduces spike frequency and lowers action-potential peak voltage slightly (3). Thus, the model simulations support the ideas that the T-type Ca2+ channels are involved in the timing of action potentials, and Na+ currents shape the upstroke of the voltage spike (3,15).

Figure 3.

Model simulations of the effect of sodium and T- and L-type calcium channel antagonists on spiking electrical activity. (A) The effect of TTX is simulated by setting gNa = 0 nS/pF (dotted blue). The simulation with default parameters given in Table 1 is shown (solid, black curve). (Aa) A zoom on action potentials from panel A. The spikes have been aligned to help comparison. (Ab) A zoom on the action potential peaks in panel Aa shows that blocking the sodium channels lowers the spike height by ∼5 mV. (B) As in panel A, but with gK(ATP) = 0.008 nS/pF. The effect of TTX is simulated by setting gNa = 0 nS/pF (dotted blue), while the control case uses the default gNa = 0.4 nS/pF (solid black). (C) Block of T-type (respectively, L-type) calcium channels is simulated by setting gCaT = 0 nS/pF (dotted blue) (respectively, gCaL = 0 nS/pF (dashed red)). The simulation with default parameters given in Table 1 is shown (solid, black curve).

High-voltage activated L- and P/Q-type Ca2+ currents are believed to be directly involved in exocytosis of secretory granules (1,3,32). Blocking L-type Ca2+ channels suppresses electrical activity (3), which is reproduced by the model (Fig. 3 C) and the lack of electrical activity is likely the main reason for the complete absence of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the presence of L-type Ca2+ blockers (3,30).

Bursting electrical activity

The membrane potential of human β-cells often shows complex behavior (1,13–15,31) resembling bursting electrical activity in rodent β-cells located in islets (4–6), though the burst period (at most a few seconds) is much shorter in human β-cells. The model is able to reproduce such rapid bursting behavior by varying, for example, the assumed properties of the delayed rectifying potassium channels. Shifting the activation curve mKv,∞ to the right (Fig. 4 A), or reducing the total conductance gKv (Fig. 4 B), results in a periodic behavior of small action potentials riding on a depolarized plateau interspersed with silent, hyperpolarized phases.

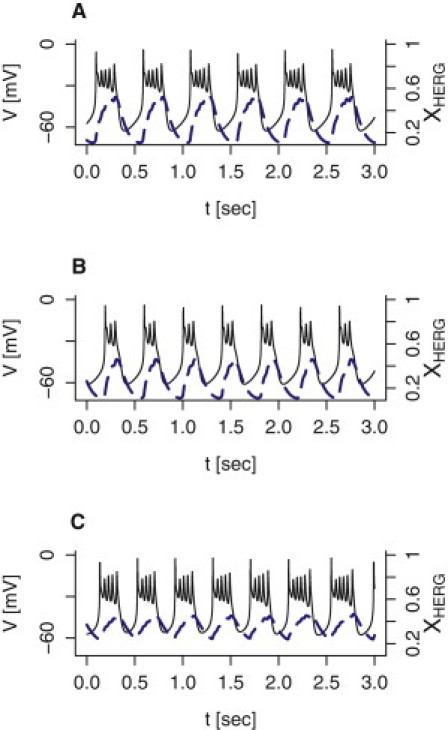

Figure 4.

Model simulations of bursting electrical activity. The membrane potential V (solid black curves; left axes) and the activation variable xHERG for the HERG current (dashed blue curves; right axes) are shown. (A) The activation function mKv,∞ for the Kv current was right-shifted by setting VmK = 18 mV. (B) The total Kv-channel conductance was reduced by setting gKv = 0.2 nS/pF. (C) The parameters for activation of the delayed rectifying potassium current were set following Herrington et al. (19): τmKv,0 = 10 ms, VmK = 5.3 mV, and nmK = −8.9 mV. The activation time-constant of HERG channels was raised to τmHERG = 200 ms, the K(ATP) conductance was set to gK(ATP) = 0.005 nS/pF, and the Na+ and K+ reversal potentials were raised slightly to VNa = 90 mV and VK = −70 mV, respectively.

Making small changes to several parameters is also a way to simulate bursting activity: using the parameters for activation of the Kv current estimated by Herrington et al. (19), assuming a twofold slower activation of HERG channels (τmHERG = 200 ms (26)), lowering the K(ATP)-conductance threefold to gK(ATP) = 0.005 nS/pF, and shifting the sodium and potassium reversal potentials slightly to VNa = 90 mV and VK = −70 mV, respectively, results in a pattern resembling fast square-wave bursting (Fig. 4 C). In the model, the HERG current is responsible for shifting between the active and silent phases, as illustrated by the sawtoothlike behavior of the activation variable xHERG (Fig. 4, dashed blue curves).

The capability of the delayed rectifier to change spiking behavior to bursting electrical activity is experimentally testable. Braun et al. (3) reported that the Kv2.1/Kv2.2 antagonist stromatoxin-1 inhibited the current believed to be carried by the delayed rectifier by ∼40–50% but had only a weak effect on electrical activity with a tendency to increase the spike height (3) and to broaden the action potentials (M. Braun, University of Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2010). Reducing the delayed rectifier conductance gKv by 50% in the model with default parameters reproduces these results. The spiking activity is slightly faster, action potentials peak slightly higher, and action potentials are broadened (Fig. 5 A). Apparently, application of stromatoxin-1 is insufficient in reducing Kv currents and inducing bursting electrical activity. To enter the bursting regime in the model with default parameters, gKv needs to be reduced by >70%.

The broad-spectrum potassium channel blocker tetraethylammonium (TEA) is more potent than stromatoxin-1, and 10 mM TEA reduces Kv currents by ∼75–80% in human β-cells (3,19), and blocks BK channels completely (3). Model simulations show that reducing gKv to 0.25 nS/pF while setting results in relaxation oscillatorlike plateau-bursting electrical activity with a nearly flat active phase (Fig. 5 B). Adding a modest degree of noise to the right-hand side of Eq. 1 induces spikes in the active phase (Fig. 5 C). Noise is inevitably present in biological recordings due to stochastic fluctuations of, e.g., ion channels, and has previously been included in β-cell models (29,39,41). Spikes can also be induced by modifying the time-constant of L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation (τhCaL = 6 ms) (not shown). The model prediction of TEA-induced bursting has been observed experimentally, because TEA application often yields bursting behavior (M. Braun, University of Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2010).

Assuming a 50% higher HERG-channel conductance in addition to the TEA-induced reductions in Kv- and BK conductances (gHERG = 0.3 nS/pF, gKv = 0.25 nS/pF, yields the classical pattern in β-cells exposed to TEA (3,33,34) of large, broad action potentials (Fig. 5 B). Finally, blocking BK channels selectively yields spiking activity with significantly higher action potentials in experiments using iberiotoxin (3) as well as in model simulations (; Fig. 5 A), suggesting an important role for BK channels in repolarization after an action potential.

Discussion

This article described the development of a model including the voltage-gated potassium, sodium, and calcium currents present in human β-cells. Model parameters were taken directly from published data whenever possible to reduce parameter tweaking to a minimum. The model satisfactorily reproduced glucose-induced spiking electrical activity (Fig. 2) as well as a series of published data of pharmacologically perturbed situations (Fig. 2 C, and Figs. 3 and 5). As for mathematical models of rodent β-cells, a central role of K(ATP) channels was established, because the spike frequency is inversely proportional to the conductance gK(ATP) (Fig. 2 A).

It has been suggested (35) that pharmacological modulation of a leak current, such as the Na+ leak channel, nonselective (i.e., NALCN), could be a target for diabetes treatment. The model supports this idea. The predicted increase in spike frequency, at fixed gK(ATP) value, induced by a raised leak conductance (Fig. 2 B), would plausibly result in augmented insulin secretion at a given glucose concentration. In addition, the value for gK(ATP) below which the model produces action potentials can be shifted by modulating the leak current. For example, raising the leak conductance twofold to gleak = 0.030 nS/pF increases the gK(ATP) threshold value to ∼0.028 nS/pF. This shift in gK(ATP) threshold value suggests that the β-cell would be active at lower glucose concentrations, but importantly and in contrast to treatment with K(ATP)-channel blockers such as sulphonylureas, the β-cell would shut down when the plasma glucose concentration falls to sufficiently, possibly dangerously, low levels.

Similarly, blocking the HERG current increases the spike frequency both in model simulations (Fig. 2 D) and experiments (18). Blockage of HERG channels also shifts the gK(ATP) threshold value for electrical activity to ∼0.031 nS/pF in the model. Thus, HERG channel blockers could show the same positive characteristics as leak current activators discussed above: increased electrical activity at a given glucose concentration, and a left shift, with respect to glucose, of the activity threshold. Indeed, HERG channel antagonists have been found to enhance insulin secretion (18,25).

With reasonable parameter changes, the model was capable of producing fast bursting activity (Fig. 4). Because bursting is most often observed in clusters of β-cells, one might speculate that small differences in current properties between single β-cells and cells located in clusters underlie the patterns. In mice, such differences have been found between isolated β-cells and cells located in islets (36). Another important difference is that human β-cells are coupled by gap junctions when located in clusters or islets (37). Mathematical modeling has shown that gap-junction coupling can turn spiking cells into bursters, especially with help from heterogeneity and noise (38–41). Preliminary simulations of two coupled model cells, using the present model of human β-cells, did not find such a beneficial effect of gap junction coupling (M. G. Pedersen., unpublished). A more detailed modeling investigation of coupled human β-cells is left for future studies.

The model did not include Ca2+-regulated SK potassium channels, which have recently been shown to exist in human β-cells (42), and likely play an important role in rodent β-cells (42,43). This omission was a choice based on the near-total absence of knowledge of the regulation of these channels in human β-cells. Moreover, including the SK channels would require a model of Ca2+ dynamics with even more unknown kinetic constants for Ca2+ pumps, buffering, and internal stores. Because the main scope of this model was to investigate whether the published characteristics of voltage-gated ion channels were sufficient to explain the observed electrical patterns, while minimizing the level of freedom for the choice of model parameters, modeling of SK channels was left for future work. A careful characterization of SK channels, of the relation between glucose concentration and K(ATP) channel conductance, of L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation, and of inactivation properties and V - and Ca2+ regulation of BK channels, will be essential for further developments of the presented model.

Several studies have found slow Ca2+ oscillations (17,44,45) and pulsatile insulin secretion (46,47) with a period of several minutes in human islets. It is tempting to speculate that these oscillations have a metabolic origin, as has been suggested for rodent islets (9,48), and that electrical activity, which was studied here, is modulated periodically due to oscillating K(ATP)-channel activity. This article could serve as the foundation for theoretical studies of the interplay among metabolism, calcium, and electrical activity, as has been done for rodent studies (9,10,12).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Matthias Braun, University of Oxford, UK, for stimulating conversations and for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, and by the European Union through a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship.

Footnotes

Morten Gram Pedersen's present address is Lund University Diabetes Centre, Department of Clinical Sciences, Clinical Research Centre, Lund University, CRC 91-11, UMAS entrance 72, SE-20502 Malmö, Sweden.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Misler S., Barnett D.W., Pressel D.M. Electrophysiology of stimulus-secretion coupling in human β-cells. Diabetes. 1992;41:1221–1228. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.10.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henquin J.-C., Dufrane D., Nenquin M. Nutrient control of insulin secretion in isolated normal human islets. Diabetes. 2006;55:3470–3477. doi: 10.2337/db06-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun M., Ramracheya R., Rorsman P. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic β-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meissner H.P., Schmelz H. Membrane potential of β-cells in pancreatic islets. Pflugers Arch. 1974;351:195–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00586918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean P.M., Matthews E.K. Electrical activity in pancreatic islet cells. Nature. 1968;219:389–390. doi: 10.1038/219389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rorsman P. The pancreatic β-cell as a fuel sensor: an electrophysiologist's viewpoint. Diabetologia. 1997;40:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s001250050706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chay T.R., Keizer J. Minimal model for membrane oscillations in the pancreatic β-cell. Biophys. J. 1983;42:181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84384-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertram R., Sherman A. Negative calcium feedback: the road from Chay-Keizer. In: Coombes S., Bressloff P.C., editors. Bursting: The Genesis of Rhythm in the Nervous System. World Scientific; Singapore: 2005. Chapter 2, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram R., Satin L., Sherman A. Interaction of glycolytic and mitochondrial dynamics drives diverse patterns of calcium oscillations in pancreatic β-cells. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1544–1555. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fridlyand L.E., Tamarina N.A., Philipson L.H. Bursting and calcium oscillations in pancreatic β-cells: specific pacemakers for specific mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;299 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00177.2010. E517-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer-Hermann M.E. The electrophysiology of the β-cell based on single transmembrane protein characteristics. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2952–2968. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.106096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen M.G. Contributions of mathematical modeling of β-cells to the understanding of β-cell oscillations and insulin secretion. J. Diabetes Sci. Tech. 2009;3:12–20. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falke L.C., Gillis K.D., Misler S. ‘Perforated patch recording’ allows long-term monitoring of metabolite-induced electrical activity and voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in pancreatic islet B cells. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pressel D.M., Misler S. Sodium channels contribute to action potential generation in canine and human pancreatic islet B cells. J. Membr. Biol. 1990;116:273–280. doi: 10.1007/BF01868466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett D.W., Pressel D.M., Misler S. Voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca2+ currents in human pancreatic islet β-cells: evidence for roles in the generation of action potentials and insulin secretion. Pflugers Arch. 1995;431:272–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00410201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabrera O., Berman D.M., Caicedo A. The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2334–2339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510790103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quesada I., Todorova M.G., Soria B. Glucose induces opposite intracellular Ca2+ concentration oscillatory patterns in identified α- and β-cells within intact human islets of Langerhans. Diabetes. 2006;55:2463–2469. doi: 10.2337/db06-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosati B., Marchetti P., Wanke E. Glucose- and arginine-induced insulin secretion by human pancreatic β-cells: the role of HERG K+ channels in firing and release. FASEB J. 2000;14:2601–2610. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0077com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrington J., Sanchez M., McManus O.B. Biophysical and pharmacological properties of the voltage-gated potassium current of human pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. 2005;567:159–175. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fridlyand L.E., Jacobson D.A., Philipson L.H. A model of action potentials and fast Ca2+ dynamics in pancreatic β-cells. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3126–3139. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly R.P., Sutton R., Ashcroft F.M. Voltage-activated calcium and potassium currents in human pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. 1991;443:175–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plant T.D. Properties and calcium-dependent inactivation of calcium currents in cultured mouse pancreatic B-cells. J. Physiol. 1988;404:731–747. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman A., Keizer J., Rinzel J. Domain model for Ca2+-inactivation of Ca2+ channels at low channel density. Biophys. J. 1990;58:985–995. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82443-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fakler B., Adelman J.P. Control of KCa channels by calcium nano/microdomains. Neuron. 2008;59:873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy A.B., Fox J.E.M., Wheeler M.B. Characterization of Erg K+ channels in α- and β-cells of mouse and human islets. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30441–30452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schönherr R., Rosati B., Wanke E. Functional role of the slow activation property of ERG K+ channels. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:753–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanguinetti M.C., Jiang C., Keating M.T. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ermentrout G. SIAM Books; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. Simulating, Analyzing, and Animating Dynamical Systems: A Guide to XPPAUT for Researchers and Students. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen M.G. Phantom bursting is highly sensitive to noise and unlikely to account for slow bursting in β-cells: considerations in favor of metabolically driven oscillations. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;248:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misler S., Barnett D.W., Falke L.C. Stimulus-secretion coupling in β-cells of transplantable human islets of Langerhans. Evidence for a critical role for Ca2+ entry. Diabetes. 1992;41:662–670. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.6.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misler S., Dickey A., Barnett D.W. Maintenance of stimulus-secretion coupling and single β-cell function in cryopreserved-thawed human islets of Langerhans. Pflugers Arch. 2005;450:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1401-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun M., Ramracheya R., Rorsman P. Exocytotic properties of human pancreatic β-cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1152:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atwater I., Ribalet B., Rojas E. Mouse pancreatic β-cells: tetraethylammonium blockage of the potassium permeability increase induced by depolarization. J. Physiol. 1979;288:561–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoppa M.B., Collins S., Rorsman P. Chronic palmitate exposure inhibits insulin secretion by dissociation of Ca2+ channels from secretory granules. Cell Metab. 2009;10:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilon P., Rorsman P. NALCN: a regulated leak channel. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:963–964. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Göpel S., Kanno T., Rorsman P. Voltage-gated and resting membrane currents recorded from B-cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J. Physiol. 1999;521:717–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serre-Beinier V., Bosco D., Meda P. Cx36 makes channels coupling human pancreatic β-cells, and correlates with insulin expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:428–439. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smolen P., Rinzel J., Sherman A. Why pancreatic islets burst but single β-cells do not. The heterogeneity hypothesis. Biophys. J. 1993;64:1668–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81539-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries G., Sherman A. Channel sharing in pancreatic β-cells revisited: enhancement of emergent bursting by noise. J. Theor. Biol. 2000;207:513–530. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Vries G., Sherman A. From spikers to bursters via coupling: help from heterogeneity. Bull. Math. Biol. 2001;63:371–391. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2001.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedersen M.G. A comment on noise enhanced bursting in pancreatic β-cells. J. Theor. Biol. 2005;235:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson D.A., Mendez F., Philipson L.H. Calcium-activated and voltage-gated potassium channels of the pancreatic islet impart distinct and complementary roles during secretagogue induced electrical responses. J. Physiol. 2010;588 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190207. 3525-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang M., Houamed K., Satin L.S. Pharmacological properties and functional role of Kslow current in mouse pancreatic β-cells: SK channels contribute to Kslow tail current and modulate insulin secretion. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:353–363. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kindmark H., Köhler M., Berggren P.O. Measurements of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration in human pancreatic islets and insulinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81309-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin F., Soria B. Glucose-induced [Ca2+]ioscillations in single human pancreatic islets. Cell Calcium. 1996;20:409–414. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchetti P., Scharp D.W., Lacy P.E. Pulsatile insulin secretion from isolated human pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 1994;43:827–830. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritzel R.A., Veldhuis J.D., Butler P.C. Glucose stimulates pulsatile insulin secretion from human pancreatic islets by increasing secretory burst mass: dose-response relationships. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:742–747. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tornheim K. Are metabolic oscillations responsible for normal oscillatory insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1997;46:1375–1380. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.9.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.