Abstract

The solid component of the tectorial membrane (TM) is a porous matrix made up of the radial collagen fibers and the striated sheet matrix. The striated sheet matrix is believed to contribute to shear impedance in both the radial and longitudinal directions, but the molecular mechanisms involved have not been determined. A missense mutation in Tecta, a gene that encodes for the α-tectorin protein in the striated sheet matrix, causes a 60-dB threshold shift in mice with relatively little reduction in outer hair cell amplification. Here, we show that this threshold shift is coupled to changes in shear impedance, response to osmotic pressure, and concentration of fixed charge of the TM. In TectaY1870C/+ mice, the tectorin content of the TM was reduced, as was the content of glycoconjugates reacting with the lectin wheat germ agglutinin. Charge measurements showed a decrease in fixed charge concentration from mmol/L in wild-types to mmol/L in TectaY1870C/+ TMs. TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice showed little volume change in response to osmotic pressure compared to those of wild-type mice. The magnitude of both radial and longitudinal TM shear impedance was reduced by dB in TectaY1870C/+ mice. However, the phase of shear impedance was unchanged. These changes are consistent with an increase in the porosity of the TM and a corresponding decrease of the solid fraction. Mechanisms by which these changes can affect the coupling between outer and inner hair cells are discussed.

Introduction

The tectorial membrane (TM) is an acellular gelatinous structure that contacts the hair cells in the organ of Corti and which contains multiple glycoproteins that are highly expressed only in the inner ear (1). Sound-induced vibrations of the organ drive radial shearing displacement of the TM relative to the reticular lamina (RL) (2). This radial motion is believed to deflect outer hair cell (OHC) bundles directly and inner hair cell (IHC) bundles through fluid interactions (3). The deflection of OHC bundles drives electromechanical processes in both cell body (4) and hair bundles (5), one or both of which deflections are believed to underlie cochlear amplification. The amplified motion increases IHC bundle deflection, which provides the majority of auditory input to the central nervous system. Consequently, the TM plays at least two mechanical roles in hearing: driving OHC motility and coupling the increased motion to IHCs.

A recent study (1) provides evidence that these two roles of the TM are separable. That study presented a mouse with a missense mutation in Tecta that caused a Y1870C amino acid substitution in α-tectorin, a protein that is specific to the TM in adult cochlea (6). In humans, a similar mutation causes a dominant 50- to 80-dB hearing loss. Mice heterozygous for this mutation (TectaY1870C/+ mice) had a 55-dB elevation in compound action potential (CAP) threshold, but only an 8-dB reduction in basilar membrane (BM) displacement (1). Taken together, these results indicate that OHC amplification is only slightly affected in TectaY1870C/+mice, but the amplified motion does not effectively drive IHC bundle deflection. Here, we report measurements of bulk compressibility, fixed charge concentration, and shear impedance of TMs from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice (hereafter referred to as wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs). These measurements illustrate the critical importance of the striated-sheet matrix to the mechanical, material, and electrical properties of the TM. Moreover, they provide some insight into how the molecular structure of the TM contributes to its two roles in cochlear function.

Methods

Preparation of the isolated TM

TectaY1870C/+ transgenic and wild-type mice 6–10 weeks old were asphyxiated with CO2 and then decapitated. The pinnae and surrounding tissues were removed and the temporal bone was isolated. The temporal bone was chipped away with a scalpel to isolate the cochlea, using a dissecting microscope for observation. The cochlea was placed in an artificial-endolymph (AE) solution containing (in mmol/L) 174 KCl, 2 NaCl, 0.02 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.3. The cochlea was widely opened to allow access to the organ of Corti. The TM was isolated from the rest of the organ by probing the organ with an eyelash. Individual pieces of TM, primarily from the midfrequency region of the cochlea (apical and middle turns), were located and transferred via pipette to a glass slide. This slide was coated with 0.3 μL of Cell-Tak bioadhesive (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) to immobilize the TM on the slide surface. This immobilization served three purposes: 1), it kept the TM from being carried out with the effluent as various fluids were perfused; 2), it allowed microfabricated probes to exert shearing forces rather than displace the bulk of the TM; 3), it allowed TM volume changes to be calculated by tracking the positions of beads on the TM and the surrounding glass slide.

Analysis of tectorial membrane proteins

Tectorial membranes were collected from cochleas of wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice at 3 weeks of age, as described previously (7). In brief, mice were killed by exposure to CO2, the labyrinths were placed in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the bony capsules surrounding the cochlea and the lateral wall of the cochlear duct were removed by dissection. The samples were briefly stained with 1% Alcian Blue for min to lightly stain the upper surface of the TM and therefore aid visualization and subsequent collection. The lightly stained TMs were then teased away from the surface of the spiral limbus with a fine dissecting needle, collected in cold PBS containing 0.1% TX-100, pelleted in a microfuge tube, and solubilized by heating to 100°C for 4 min in reducing SDS PAGE sample buffer. The solubilized TM proteins from a roughly equivalent number of TMs were separated on 8.25% acrylamide gels and visualized by one of three methods. One gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant blue to make all protein bands visible. Two others were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes that were then stained with 1), a mixture of polyclonal sera raised to chicken Tecta and chicken Tectb (R9 and R7) (8); or 2), biotinylated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, Vector, Burlingame, CA). Bound primary antibodies and biotinylated WGA were labeled with alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Vector), respectively, and the alkaline phosphatase was detected with NBT/BCIP (nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate p-toluidine salt). Coomassie stained gels and blots were quantified using the National Institutes of Health Image program, and the intensities of the bands observed on the blots were expressed as a function of the intensity of the Type II collagen band in the corresponding Coomassie stained gel.

Measuring fixed charge concentration

The methods for measuring fixed-charge concentration are as published previously (9). Fixed-charge groups within the TM attract mobile counterions and thus establish an electrical potential between the TM and the bath according to the Donnan relation (10). When the TM forms an electrical conduit between a reference bath and a test bath with a differing ionic composition, the Donnan potentials formed at the two TM-bath interfaces need not be equal. The resulting potential difference between baths is given by

| (1) |

where VD is the potential between baths, R is the molar gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, F is Faraday's constant, cf is the concentration of fixed charge within the TM, and CR and CT are the sums of concentrations of all ions in the reference and test baths, respectively.

To measure this potential we used a planar clamp technique, as described previously (9,11,12). The TM was placed over a narrow aperture separating two baths. The reference bath above the TM was AE with a constant KCl concentration of 174 mM. Various AE-based test baths were perfused with KCl concentrations of 21, 32, 43, 87, and 174 mM. The electrical potential between baths was measured with Ag/AgCl electrodes, and coupled through an amplifier (DAM60-G Differential Amplifier, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) to a multimeter (TX3 True RMS Multimeter, Tektronix, Portland, OR) connected to a computer. DC and AC potentials were read from the multimeter by the computer every 2–3 s. Measurements with AC potentials as large as the DC ones indicated the presence of electrical noise and were discarded. Each test bath was perfused for 10–30 min at a time, and each bath was perfused at least twice over the course of an experiment.

Measuring stress-strain relation

The methods used to measure the stress-strain relation of the TM are as published previously (9,13). Briefly, TMs from TectaY1870C/+ and wild-type mice were isolated and affixed to a glass slide. The TM was immersed in AE containing various concentrations of polyethylene glycol (PEG) with a molecular weight (MW) of 511 kDa. The applied osmotic pressure for each solution ranged from 0 to 10 kPa and was computed from the concentration and molecular weight of PEG as described previously (13). The surface of the TM was decorated with fluorescent microspheres (i.e., beads), and sets of 100 images of the TM at focal depths separated by 1 μm were taken once per minute. The positions of beads on the surface were tracked to determine changes in TM height with an accuracy of 0.1 μm. The z-component of the strain, ɛz, is given by

| (2) |

where vz is the ratio of bead height in the presence of PEG to that in its absence. The relation between osmotic pressure, , and TM strain was characterized by a power law, , with A and b determined by a least-squares fit to the measurements. The longitudinal modulus, a basic material property of the TM, is defined by the derivative of this relation (13).

Measuring shear impedance

Shearing forces were applied in both the radial and longitudinal direction by means of a microfabricated probe, as described previously (14). The probe consisted of a base driven by a piezoactuator, a 30 × 30 μm shearing plate that contacted the TM, and flexible arms that connected the base to the plate. TM displacements of ∼0.5–1 μm were applied by means of the piezoactuator at audiofrequencies of 10–9000 Hz. Stroboscopic illumination was used to collect images of the TM and the probe at eight evenly spaced phases of the stimulus. Optical flow algorithms were used to measure displacements of both the probe and the TM relative to the base (15). The same algorithms were used to measure TM displacement as a function of distance from the probe. These measurements were made in both the radial and longitudinal directions in response to both radial and longitudinal shear forces.

The impedance of the TM was calculated from the displacement data. In the frequency domain, the impedance, , is related to the applied force, , and the measured displacements of the probe base, , and shearing plate, , by

| (3) |

where and are the stiffness and damping, respectively, of the TM; is the velocity of the TM and shearing plate; and kmp is the stiffness of the microfabricated probe. As in the previous study, the frequency dependence of TM shear impedance showed no significant contribution from mass, so the mass term was left out of Eq. 3. For longitudinal forces at frequencies kHz, the mass of fluid constrained to move with the probe introduced a decrease in impedance magnitude and a corresponding phase lead of as much as 45°.

Genotyping of mice and animal care

Genotyping was done by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Comparative Medicine according to published methods (16). The care and use of animals reported in this study were approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care.

Results

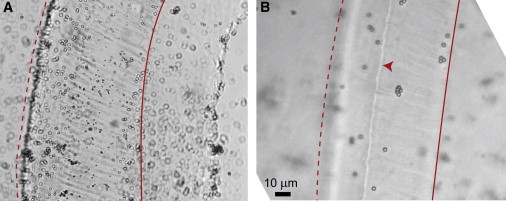

TectaY1870C/+ TMs have less prominent longitudinal fibers and Hensen's stripe compared to wild-types

Fig. 1 shows light micrographs of TMs from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice. In contrast to images of fixed tissue (1), unfixed TMs had no significant holes or gaps. The radial fibrillar structure of the TM was clearly visible in both wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs. The density of radial fibrils was ∼11 fibers per 20 × 20-μm area for both wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs. However, there are significant structural changes resulting from the mutation. Hensen's stripe, which may play a critical role in IHC bundle deflection (17), is absent in TectaY1870C/+ TMs. Other structures, such as the longitudinal fibers that make up the covernet and the trabeculae, were less prominent or absent in TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice. Finally, the TMs of TectaY1870C/+ mice were significantly thinner overall than those of wild-type mice.

Figure 1.

Micrographs of TM segments from a TectaY1870C/+ mouse (A) and a wild-type mouse (B). Dotted lines denote the marginal band at the outer edge of the TM. Solid lines denote the boundary between the body of the TM and the limbal attachment. Circles are microspheres used to track TM volume. In TectaY1870C/+ mice (A), radial fibers are prominent, but Hensen's stripe is absent. In B, Hensen's stripe is indicated by the arrowhead.

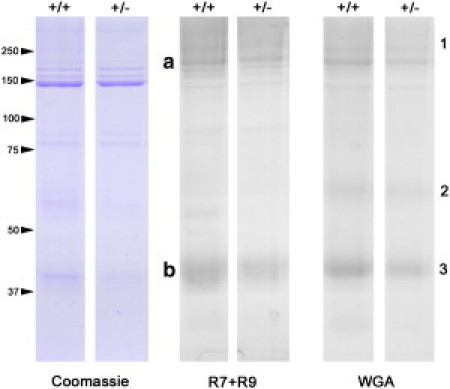

Protein composition of TM

The effect of the TectaY1870C/+ mutation on the protein composition of the TM was investigated by making gels and western blots of proteins from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs. Fig. 2 shows gels stained with Coomassie and western blots stained either with a mixture of R7 and R9 or with biotinylated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA). The leftmost gels were stained with Coomassie, which stains all proteins. The center blots were stained with R9, an anti-α-tectorin stain, and R7, an anti-β-tectorin stain. The rightmost blots were stained with biotinylated WGA, which recognizes all α-tectorin fragments (high, medium, and low) and β-tectorin, and should detect n-acetyl glucosamine and sialic acid residues associated with these bands.

Figure 2.

Pairs of wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs juxtaposed to compare protein composition. (Left) Coomassie-stained gels (TMs/lane). (Center) Western blots stained with R7 and R9 (TMs/lane), with locations of α- and β-tectorin indicated by a and b, respectively. (Right) Western blots stained with WGA (TMs/lane), with glycosylated fragments of α- and β-tectorin labeled 1–3.

The Coomassie-stained gels demonstrate that wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs have a similar polypeptide profile. As it is not possible to recover the entire TM from the cochlea by dissection, the contribution of the tectorins to total protein composition was determined relative to the amount of Type II collagen present in each sample, as determined by the density of the darkest band in Coomassie stained gels. Densitometric analysis of blots stained with a mixture of antibodies to Tecta and Tectb indicated that band a (the high-molecular-mass α-tectorin fragment) was reduced by in the TectaY1870C/+ mutants, whereas band b (a mixture of β-tectorin and the low molecular mass α-tectorin fragment) was reduced by . WGA staining of the second set of blots reveals three bands. The densities of bands 1–3 (from the top) for TectaY1870C/+ TMs were 50–75% of those of wild-types. These results indicate that the TectaY1870C/+ mutation causes a slight reduction in the tectorin content of the TM, but a larger reduction in WGA-reactive glycoconjugates that may contain charged glucosamine and sialic acid residues.

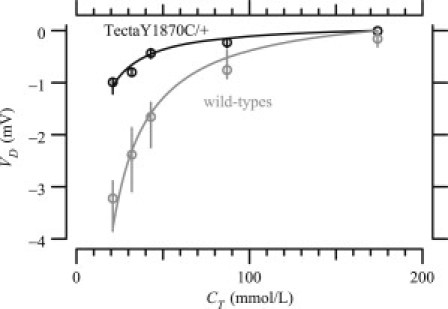

TM fixed-charge concentration

There is evidence that α-tectorin is a keratan sulfate proteoglycan (18), and the observed reduction in glycosylated tectorins in the TectaY1870C/+ mouse was predicted to alter the fixed-charge concentration of the TM. To investigate this possibility, the fixed-charge concentration, cf, was estimated by measuring Donnan potentials for TM segments from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice. Fig. 3 summarizes these potential measurements. For both wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TM segments, the measured potential difference became more negative for smaller KCl concentrations. The measured potential differences were less negative at a given bath concentration for TectaY1870C/+ TMs compared to wild-types. It was often difficult to maintain a proper seal with TectaY1870C/+ TMs, so the voltage measurements tended to be unstable. The results shown here are for three TM segments for which the measurements remained stable over the time course of the experiment.

Figure 3.

Potential difference, VD, between two baths as a function of KCl bath concentration, CT, for TM segments from wild-type () and TectaY1870C/+ () mice. Circles are the median values and vertical lines show the interquartile ranges of the measurements. The solid line is the least-squares fit of the medians to Eq. 1. The median and interquartile ranges for the least-squares fits of cf were mM and mM for TM segments from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice, respectively.

The cf values for TM segments from TectaY1870C/+ and wild-type mice were determined by fitting Eq. 1 to the measured voltages. The voltages predicted from the fits fell within the interquartile range of the measurements for nearly all bath concentrations. The best fit cf values for wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs were (TMs) and mmol/L (TMs), respectively. This reduction is larger than the reduction in charged glycoconjugates measured using blots.

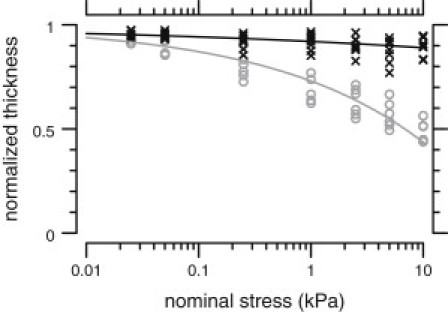

Effect of osmotic stress

To determine whether the TectaY1870C/+ mutation affected the longitudinal modulus of the TM, the normalized TM thickness (vz) was measured in response to applied osmotic stress. Fig. 4 shows this relation for TM segments from wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ mice. At all applied stresses, the thickness change was smaller for TectaY1870C/+ TMs than for wild-types. This difference increased with the magnitude of stress. At a nominal applied osmotic stress of 10 kPa (see below), the normalized thickness was for TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice, compared to for TMs from wild-type mice. Moreover, the incremental volume change for an incremental stress (i.e., the slope of the stress-strain relation) was lower for TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice.

Figure 4.

Relation between nominal osmotic stress and TM volume change for TectaY1870C/+ (, black exes) and wild-type (, gray circles) TM segments. The scatter in the measurements was larger for TectaY1870C/+ TMs than for wild-types. Lines represent power-law fits to the data: for wild-types and for TectaY1870C/+ TMs, where vz and σ are normalized volume and stress, respectively.

The relation between osmotic stress and thickness roughly followed a power-law relation. For wild-type TMs, the best-fit power-law relation was (TMs), with in kPa. For TectaY1870C/+ TMs, this relation was (TMs). This power-law relation was compressively nonlinear for both wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs. However, the slope of this relation was significantly shallower for TectaY1870C/+ TMs.

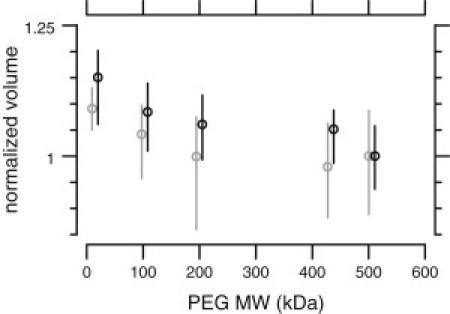

These results can be explained by an increase in the TM longitudinal modulus in TectaY1870C/+ mice or by a decrease in the effective osmotic pressure applied to the TM by PEG. We have previously shown that for wild-type TMs, only sufficiently large PEG molecules apply their full osmotic stress to the TM (13). To test whether PEG was applying its full osmotic stress to TectaY1870C/+ TMs, we measured the vz of wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs as a function of PEG molecular weight (MW) at a nominally constant osmotic pressure of 250 Pa. As previously reported (13), vz was constant for wild-type TMs for PEG MW ≥200 kDa, corresponding to a maximum pore size of ≤22 nm. For TectaY1870C/+ TMs, vz decreased consistently with PEG MW up to 511 kDa (Fig. 5), corresponding to a maximum pore size of ≥36 nm. The increased pore size of TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice suggests that some PEG entered these TMs. Because the relationship between concentration and osmotic pressure for PEG solutions is highly nonlinear (19), the actual osmotic pressure applied to TectaY1870C/+ TMs is likely to be significantly lower than suggested by Fig. 4.

Figure 5.

TM normalized thickness versus PEG MW in isosmotic solutions for wild-type (gray) and TectaY1870C/+ (black) mice. For each MW of PEG, the concentration was adjusted to exert a nominal osmotic pressure of 250 Pa. Thickness was normalized to that measured using 511 kDa PEG. Circles denote the median thickness, vertical lines show the interquartile range. The values for wild-type TMs have been offset horizontally for clarity. Thickness for wild-type TMs levels off for PEG with MW ≥ 200 kDa. For TectaY1870C/+ TMs, thickness continues to decrease with increasing MW.

TM shear impedance

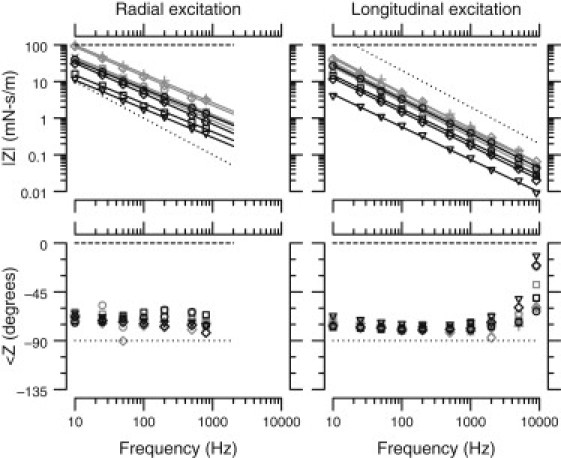

Because the TM is subjected to shearing forces in the cochlea, TM shear impedance is an important mechanical property of the cochlea. To investigate the effect of the TectaY1870C/+ mutation on TM shear impedance, we measured the response of the TM to forces applied by a microfabricated probe at frequencies from 10 to 9000 Hz. Forces were applied in both the radial and longitudinal directions. Fig. 6 shows the magnitude and phase of shear impedance for TM segments from wild-type () and TectaY1870C/+ () mice. The TectaY1870C/+ mutation reduced the magnitude of TM shear impedance by dB for radial forces and dB for longitudinal forces. That is, the TectaY1870C/+ mutation caused the magnitude of TM shear impedance to decrease by roughly a factor of 3. The frequency dependence of TM shear impedance was unchanged by the mutation. The ratio of radial to longitudinal impedance at 10 Hz was for TectaY1870C/+ and for wild-type mice. The phase of shear impedance was nearly constant with frequency except above 2 kHz for longitudinal forces, where impedance phase is affected by the surrounding fluid. For wild-type TMs, the phase below 4 kHz averaged and for radial and longitudinal forces, respectively. For TectaY1870C/+ TMs, the corresponding values were and , respectively. These values were not significantly different, indicating that the phase of shear impedance was unaffected by the mutation. Moreover, the elastic contribution to TM impedance was roughly five times larger than the viscous contribution for both wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs.

Figure 6.

Magnitude (upper) and phase (lower) of shear impedance as a function of frequency for both radial (left) and longitudinal (right) excitation. The plot symbols show the individual measurements for wild-type (gray) and TectaY1870C/+ (black) TMs. Solid lines show the best fit of a power-law relation to the magnitude of shear impedance from each TM. In the radial direction, these power-law relations had slopes of and for TectaY1870C/+ and wild-type TMs, respectively. In the longitudinal direction, these slopes were and , respectively. The magnitude of shear impedance was consistently lower for TectaY1870C/+ TMs compared to wild-types in both the radial and longitudinal directions. However, the phase was similar for both groups. Dotted and dashed lines show the magnitude and phase predicted for purely elastic and purely viscous materials, respectively.

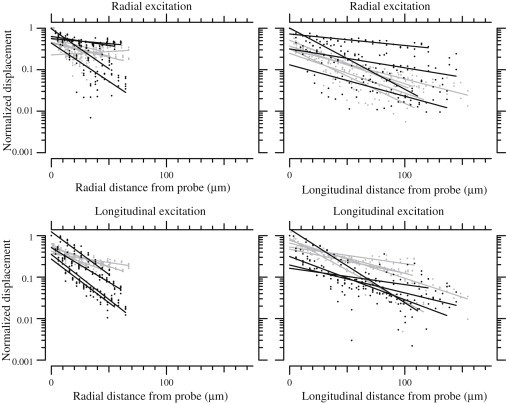

The change in magnitude, but not phase, of TM shear impedance suggests that a smaller volume of TM was sheared in TectaY1870C/+ mice. To test this possibility, we measured the shear displacement of the TM as a function of distance from the force probe. In response to both radial and longitudinal forces, TM displacement fell exponentially with distance from the probe. For three out of four experimental conditions, TM displacement at distances >50 μm from the shearing probe was consistently smaller for TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice compared to wild-types (Fig. 7). In the fourth condition, displacement versus longitudinal distance for radial forces, no significant difference could be seen. This result confirms that the volume of TM sheared was reduced in TectaY1870C/+ mice.

Figure 7.

Normalized displacement magnitude as a function of distance from the probe for applied shear forces. The plots show displacement for TMs from wild-type (gray) and TectaY1870C/+ (black) mice. Dots represent measurements and lines represent exponential fits for each TM. The four subplots show displacement as a function of radial and longitudinal distance for both radial and longitudinal forces.

Discussion

α-Tectorin provides backbone for fixed charge

The solid fraction of the TM has two primary structural components, the radial collagen fibrils and the striated-sheet matrix (20). The radial fibers are primarily made up of collagen types II, IX, XI, and otogelin, and the striated-sheet matrix is made up mostly of α- and β-tectorin. In the TM, α-tectorin forms a keratan sulfate proteoglycan (21) associated with glucosamine and sialic acid. Since these glycoconjugates are negatively charged at physiological pH, α-tectorin and associated structures are key contributors to the concentration of fixed charge within the TM.

The gel densitometry measurements suggest that the concentration of glycoconjugates in the TM was reduced by slightly less than a factor of 2 by the TectaY1870C/+ mutation. In contrast, the electrical measurements suggest that fixed-charge concentration was reduced by nearly 70%. The electrical measurements may overestimate the reduction in charge, because changes in TM porosity (see below) can introduce electrical shorts that reduce the estimated charge concentration. A conservative estimate is that the TectaY1870C/+ mutation caused a factor-of-2 reduction in fixed-charge concentration. The change in fixed-charge concentration cannot be attributed to the amino acid substitution in α-tectorin itself, since tyrosine and cysteine are both polar. Thus, we can conclude that the effect of the mutation on fixed-charge concentration was secondary to changes in the glycosylation status of the tectorins.

Estimating pore size of TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice

Measurements of TM volume changes as a function of PEG MW show that the maximum pore size of TMs from TectaY1870C/+ mice is at least 50% larger than for wild-types. This increase in porosity allows some PEG to enter the TM, reducing the effective osmotic pressure applied to TectaY1870C/+ TMs. Although we cannot determine an upper bound on the pore size of TectaY1870C/+ mice, we can estimate the fraction of PEG that can enter the TM. If we assume that the difference in vz between wild-type and TectaY1870C/+ TMs in Fig. 4 is due entirely to changes in applied osmotic pressure (i.e., the material properties themselves did not change), then at a nominal osmotic pressure of 10 kPa, the actual osmotic pressure applied to TectaY1870C/+ TMs was ∼25 Pa. Based on the nonlinear relation between PEG concentration and osmotic pressure, <5% of the PEG in solution contributes to this osmotic pressure. The ease with which PEG apparently enters TectaY1870C/+ TMs suggests that the pore size of TectaY1870C/+ TMs is significantly larger than the 36-nm radius of 511 kDa PEG. This increase in pore size likely reduces the solid fraction of the TM, explaining both the decrease in cf and the reduction in shear impedance observed here.

The contribution of striated-sheet matrix to TM shear impedance

The most prominent features of the TM under light microscopy are the radial collagen fibers. Some models suggest that the radial stiffness of the TM is dominated by these collagen fibers (22). However, a previous study in our lab showed that the primary role of these fibers in response to shear forces is to provide a mechanical coupling across the width of the TM (9). This mechanical coupling selectively increased the magnitude of radial shear impedance, but did not alter the relative contribution of elasticity and damping to this impedance.

Fig. 6 shows that TectaY1870C/+ mutation decreased the shear impedance in the radial and longitudinal direction by 10.1 ± 1.4 dB and 10.3 ± 1.6 dB, respectively. Because this decrease was independent of the direction of force application, it cannot be attributed to changes in the collagen fibers. Instead, it is likely due to reduced coupling in the striated-sheet matrix, associated with an increase in porosity. This reduced coupling can be seen directly in measurements of the reduction in shear displacement as a function of distance from the probe.

It is intriguing that this reduction was not seen in the longitudinal direction in response to radial forces. This direction is of particular interest, because it is the direction in which TM traveling waves propagate (23). Thus, TectaY1870C/+ mice are likely to have little change in TM traveling waves, which may explain the small change in the sensitivity of basilar membrane motion (1). We speculate that radial collagen fibrils in the TM may reinforce the longitudinal propagation of radial TM motion, and that therefore, they play a significant role in the propagation of TM traveling waves. A different mutation in Tecta causes significant changes in TM morphology without reducing the excitation of OHCs contacted by the TM, further supporting this conclusion (24).

Changes in TM properties explain theshold elevation in TectaY1870C/+ mice

This study reveals several changes in TM mechanical and material properties that provide likely explanations for the reduction in IHC sensitivity of TectaY1870C/+ mice. First, the reduction in TM shear impedance measured here is associated with a significant drop in TM shear displacement as a function of radial distance from the site of force application. This change dramatically reduces the ability of OHCs to drive IHC bundle deflection through force production. Second, Hensen's stripe is missing from TMs of TectaY1870C/+ mice. If the TM moves radially in response to sound, as is commonly believed ((2,25,26), but see Chan and Hudspeth (27)), the absence of Hensen's stripe can further reduce the drive to IHC bundle deflection (17). This combination of a reduction of power transmission along the TM and a reduction in local IHC bundle excitation can account for the increased neural threshold in the presence of normal OHC activity. Additional changes observed here can further reduce IHC excitation; an increase in the porosity of the TM can reduce radial fluid flow driven by transverse TM motion (28), and the reduced cf can decrease Ca2+ sequestration by the TM, which may reduce the efficiency of mechanoelectrical transduction (29).

Acknowledgments

We thank the people in the Micromechanics Group at MIT and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and criticism.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-DC00238. W.G. and R.G. were supported in part by an NIH training grant to the Harvard-MIT Speech and Hearing Biosciences and Technology Program, and K.M. was supported in part by NIH grant R01-DC03544. G.R. was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Kinuko Masaki's present address is Advanced Bionics Corporation, 28515 Westinghouse Pl., Valencia, CA 91355.

References

- 1.Legan P.K., Lukashkina V.A., Richardson G.P. A deafness mutation isolates a second role for the tectorial membrane in hearing. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1035–1042. doi: 10.1038/nn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gummer A.W., Hemmert W., Zenner H.-P. Resonant tectorial membrane motion in the inner ear: its crucial role in frequency tuning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8727–8732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis H. A mechano-electrical theory of cochlear action. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1958;67:789–801. doi: 10.1177/000348945806700315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownell W.E., Bader C.R., de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy H.J., Crawford A.C., Fettiplace R. Force generation by mammalian hair bundles supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–883. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legan P.K., Lukashkina V.A., Richardson G.P. A targeted deletion in α-tectorin reveals that the tectorial membrane is required for the gain and timing of cochlear feedback. Neuron. 2000;28:273–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson G.P., Russell I.J., Bailey A.J. Polypeptide composition of the mammalian tectorial membrane. Hear. Res. 1987;25:45–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knipper M., Richardson G., Zimmermann U. Thyroid hormone-deficient period prior to the onset of hearing is associated with reduced levels of β-tectorin protein in the tectorial membrane: implication for hearing loss. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:39046–39052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masaki K., Gu J.W., Aranyosi A.J. Col11a2 deletion reveals the molecular basis for tectorial membrane mechanical anisotropy. Biophys. J. 2009;96:4717–4724. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss T., Freeman D. Equilibrium behavior of an isotropic polyelectrolyte gel model of the tectorial membrane: The role of fixed charges. Aud. Neurosci. 1997;3:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigworth F.J., Klemic K.G. Patch clamp on a chip. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2831–2832. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75625-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaffari, R., A. J. Aranyosi, and D. M. Freeman. 2005. Measuring the electrical properties of the tectorial membrane. In Abstracts of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Midwinter Research Meeting. Association for Research in Otolaryngology, New Orleans, LA. 240.

- 13.Masaki K., Weiss T.F., Freeman D.M. Poroelastic bulk properties of the tectorial membrane measured with osmotic stress. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2356–2370. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu J.W., Hemmert W., Aranyosi A.J. Frequency-dependent shear impedance of the tectorial membrane. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2529–2538. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis C.Q., Freeman D.M. Using a light microscope to measure motions with nanometer accuracy. Opt. Eng. 1998;37:1299–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown M.R., Tomek M.S., Smith R.J. A novel locus for autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss, DFNA13, maps to chromosome 6p. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:924–927. doi: 10.1086/514892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele C.R., Puria S. Multi-scale model of the organ of Corti: IHC tip link tension. In: Nuttall A., editor. Auditory Mechanisms: Processes and Models. World Scientific; Singapore: 2006. pp. 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Killick R., Richardson G.P. Antibodies to the sulphated, high molecular mass mouse tectorin stain hair bundles and the olfactory mucus layer. Hear. Res. 1997;103:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasse H., Kany H.P., Maurer G. Osmotic virial coefficients of aqueous poly(ethylene glycol) from laser-light scattering and isopiestic measurements. Macromolecules. 1995;28:3540–3552. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasko J.A., Richardson G.P. The ultrastructural organization and properties of the mouse tectorial membrane matrix. Hear. Res. 1988;35:21–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodyear R.J., Richardson G.P. Extracellular matrices associated with the apical surfaces of sensory epithelia in the inner ear: molecular and structural diversity. J. Neurobiol. 2002;53:212–227. doi: 10.1002/neu.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavara, N., and R. Chadwick. 2008. Measurement of anisotropic mechanical properties of cochlear tectorial membrane. In Abstracts of the Thirty-First Midwinter Research Meeting. Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Phoenix, AZ.

- 23.Ghaffari R., Aranyosi A.J., Freeman D.M. Longitudinally propagating traveling waves of the mammalian tectorial membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16510–16515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia A., Gao S.S., Oghalai J.S. Deficient forward transduction and enhanced reverse transduction in the alpha tectorin C1509G human hearing loss mutation. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:209–223. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwislocki J.J., Kletsky E.J. Tectorial membrane: a possible effect on frequency analysis in the cochlea. Science. 1979;204:639–641. doi: 10.1126/science.432671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page, S., A. J. Aranyosi, and D. M. Freeman. 2006. An isolated gerbil cochlea preparation for measuring sound-induced micromechanical motions. In Abstracts of the Twenty-Ninth Midwinter Research Meeting. Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Baltimore, MD.

- 27.Chan D.K., Hudspeth A.J. Ca2+ current-driven nonlinear amplification by the mammalian cochlea in vitro. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nn1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nowotny M., Gummer A.W. Nanomechanics of the subtectorial space caused by electromechanics of cochlear outer hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2120–2125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511125103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gummer, A. W., and A. P. Udayashankar. 2009. Regulation by the tectorial membrane of calcium concentration in the subtectorial space. In Abstracts of the Thirty-Second Midwinter Research Meeting. Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Baltimore, MD.