Abstract

Francisella tularensis is a zoonotic bacterium that must exist in diverse environments ranging from arthropod vectors to mammalian hosts. To better understand how virulence genes are regulated in these different environments, a transcriptional response regulator gene (genome locus FTL0552) was deleted in F. tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS). The FTL0552 deletion mutant exhibited slightly reduced rates of extracellular growth but was unable to replicate or survive in mouse macrophages and was avirulent in the mouse model using either BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice. Mice infected with the FTL0552 mutant produced reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines, exhibited reduced histopathology, and cleared the bacteria quicker than mice infected with LVS. Mice that survived infection with the FTL0552 mutant were afforded partial protection when challenged with a lethal dose of the virulent SchuS4 strain (4 of 10 survivors, day 21 postinfection) when compared to naive mice (0 of 10 survivors by day 7 postinfection). Microarray experiments indicate that 148 genes are regulated by FTL0552. Most of the genes are downregulated, indicating that FTL0552 controls transcription of genes in a positive manner. Genes regulated by FTL0552 include genes located within the Francisella pathogenicity island that are essential for intracellular survival and virulence of F. tularensis. Further, a mutant in FTL0552 or the comparable locus in SchuS4 (FTT1557c) may be an alternative candidate vaccine for tularemia.

Introduction

Francisella Tularensis is a small, nonmotile, aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus, the only genus belonging to the Family Francisellaceae and a member of the γ-subclass of proteobacteria. This bacterium was first discovered by McCoy and Chapin in 1911 following an outbreak of a plaguelike illness in ground squirrels in Tulare County, California (Hollis et al., 1989; Forsman et al., 1994; McLendon et al., 2006). This bacterium is a hardy, non-spore-forming organism, with a thin lipopolysaccharide-containing envelope that can persist in the environment for long periods of time in low-temperature water, moist soil, hay, straw, and decaying animal carcasses (www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/tularemia) (McLendon et al., 2006). There are five subspecies of F. tularensis found in the Northern Hemisphere, but only two, subsp. tularensis and subsp. holartica, cause human disease (McLendon et al., 2006). The most virulent subsp., tularensis (type A), is the causative agent of the zoonotic disease tularemia. It is predominantly found in North America and is associated with lethal pulmonary infections. Recently, studies further divided the subsp. tularensis into two genetically distinct clades: type A1, found predominantly in California, the Midwest, and Massachusetts, and A2, found predominantly in California and the mountain states (McLendon et al., 2006). The second subsp. holartica (type B), also known as palearctica, rarely causes a fatal disease in humans and is predominantly found in Europe and Asia. An attenuated live vaccine strain (LVS), derived from a Russian strain of subsp. holartica, has been described and shown to offer protection to humans against naturally and laboratory acquired tularemia but remains as virulent to mice as wild-type subsp. holartica (Golovliov et al., 2003a). LVS causes disease in mice that is virtually indistinguishable from that caused in humans by the highly virulent strains (Eigelsbach and Downs, 1961; Anthony and Kongshavn, 1987; Fortier et al., 1991). The LVS strain is not fully licensed as a vaccine but is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The third subsp., novicida, has been characterized as a relatively non-virulent strain, with only two documented cases of tularemia caused by novicida in two severely immunocompromised patients in North America. The most recently identified subsp. of Francisella is mediasiatica. It is primarily found in Asia, but very little is know about this subspecies or its association with human disease.

F. tularensis subsp. tularensis has been classified by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Strategic Planning Group as a Category A agent of high priority, due to its virulence, low infective dose, and its potential for transmission by aerosols (Greenfield et al., 2002). In humans, an infectious dose for type A strains can be as low as 10 bacteria for respiratory (McCrumb, 1961; Saslaw et al., 1961b) or intradermal routes (Saslaw et al., 1961a).

Little is known about the virulence mechanisms of F. tularensis (Sjöstedt, 2003; Michell et al., 2006). Macrophages are believed to be the primary host cell for survival and replication of the bacterium (McLendon et al., 2006). The ability of Francisella species to survive and multiply in macrophages plays a crucial role in its pathogenesis (Anthony et al., 1991; Fortier et al., 1994). However, the exact niche occupied by this organism and the specific virulence factors modulating the organism's intracellular growth and survival are not clearly defined (McLendon et al., 2006). How the phagosome membrane is disrupted is yet to be defined.

The pathogen–host relationship is complex, and successful infection depends upon the expression of a number of bacterial genes that are adapted for infection of the host (Finlay and Falkow, 1989, 1997; Hensel and Holden, 1996; Knodler et al., 2001). In the case of the vector-borne zoonotic bacterium F. tularensis, it must survive and grow under a wide range of conditions, including arthropod vectors, such as ticks, as well as in warm-blooded vertebrate hosts. The synthesis of bacterial virulence factors in these changing environments is highly regulated and responds to environmental cues, such as growth phase, temperature, osmotic stress, and changing concentration of extracellular ions such as Mg2+, Ca2+, and Fe2+ (Mekalanos, 1992).

Two-component signal transduction systems (TCS), reviewed by Stock et al. (2000), are the most prevalent strategies bacteria use to couple environmental signals to adaptive responses, and play an important role in bacterial survival under environmental stress including survival within macrophages (Miller, 1991). They typically contain a membrane-bound sensor kinase and a cytoplasmic response regulator. The sensor kinase detects environmental signals received at the surface of the cells, resulting in autophosphorylation of a histidine residue in the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail. The response regulator is comprised of two highly conserved domains: the regulatory/receiver domain and the effector domain. The receiver domain acts as a phosphorylation-activated switch that controls an associated effector domain. The sensor kinase transfers the phosphate group to a conserved active-site aspartic acid residue within the cytoplasmic response regulator receiver domain, shifting the equilibrium to an active state. Phosphorylation modifies the effector domain's ability to act as a DNA-binding, transcription activator controlling multiple genes (Soncini et al., 1996; Stock and Guhaniyogi, 2006). Inactivation of TCS results in reduced bacterial virulence (Groisman, 2001). For example, Salmonella phoP/phoQ genes control the expression of more than 40 genes, including proteins encoded by virulence-associated genes important for intramacrophage survival during infection (Miller and Mekalanos, 1990; Lejona et al., 2003). The PhoQ sensor kinase responds to changes in the external environment such as magnesium concentrations to activate the PhoP response regulator, and results in the transcription of genes essential for survival of the bacteria in the changing environment (Soncini et al., 1996). PhoP also controls virulence in Yersinia pestis (Oyston et al., 2000), Shigella flexneri (Moss et al., 2000), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Perez et al., 2001), Bordetella pertussis (Kinnear et al., 2001), and Neisseria meningitidis (Johnson et al., 2001; Newcombe et al., 2004). A TCS response regulator, PmrA, was recently described in F. tularensis subsp. novicida. PmrA is an orphan member of typical two-component regulatory systems. PmrA shares high similarity (44%) with the Salmonella PmrA response regulator. F. tularensis subsp. novicida mutants lacking the pmrA gene were defective for survival and growth within macrophages and offer complete protection in mice against homologous challenge but did not protect the mice against challenge with the SchuS4 strain. DNA microarray analysis identified 65 genes regulated by PmrA, some of which are located within the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI) (Mohapatra et al., 2007). However, the F. tularensis subsp. novicida PmrA protein appears to be an orphan member of a two-component regulatory system.

It was the goal of this project to identify and characterize genes encoding potential two-component regulatory systems in F. tularensis that may be involved in regulation of virulence factor genes. In order to identify potential response regulator genes that activate genes necessary for bacterial virulence, we searched the F. tularensis LVS genome using a consensus amino acid sequence derived from the phoP response regulator genes from other gram-negative bacteria. One locus, FTL0552, was identified by the similarity of its protein product to the PhoP response regulator consensus sequence. The FTL0552 locus was annotated in the genome sequence as a transcriptional response regulator. The corresponding locus in F. tularensis SchuS4 (FTT1557c) is highly conserved.

In this report we describe the construction of a deletion mutant for FTL0552 in F. tularensis LVS. This mutant was defective for survival in mouse macrophages and was avirulent in the mouse model. Further, mice infected with the FTL0552 mutant exhibited reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokine production and reduced evidence of histopathology in affected tissues, and, correspondingly, reduced systemic infection and rapid clearance of the bacterium. Challenge studies of mice surviving infection with the FTL0552 mutant using the virulent SchuS4 strain suggest that some level of protective immunity is afforded to these mice. Microarray studies revealed 148 genes regulated by FTL0552, including genes located within the FPI that are essential for intracellular survival. Our results support a major role for the FTL0552 gene product in controlling expression of virulence genes in F. tularensis.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

F. tularensis LVS, kindly provided by Scott Bearden, CDC, Fort Collins, Colorado, was grown on agar consisting of GC agar base (Remel, Lenexa, KS) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% bovine hemoglobin, and 1% IsoVitaleX™ (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), and incubated at 37°C. The F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant was grown on the same agar with the addition of 50 μg/mL kanamycin. For some experiments, bacteria were grown in Mueller Hinton II (MH) broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 0.1% glucose, 2% IsoVitaleX, and 33 μM ferric pyrophosphate (Maier et al., 2004). For bacterial growth analysis, MH broth cultures were incubated at 37°C with aeration and the OD550 was measured at various time points.

Cell lines

The immortalized mouse macrophage cell line (J774A.1) was cultured in Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% FBS, 4.5 g/mL glucose and L-glutamine, and 50 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Mouse peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were collected from thioglycolate-treated BALB/c mice, washed, and resuspended in medium containing 10% FBS, 0.33 μL/mL 2-mercaptoethanol, and L-glutamine.

Identification of the FTL0552 response regulator gene

Bacterial PhoP protein sequences were retrieved from (NCBI) GenBank and aligned using the PileUp Program for aligning multiple sequences from the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) Wisconsin Package Version 10 (Devereux et al., 1984; Feng and Doolittle, 1987). The consensus sequence, generated from the alignment of bacterial PhoP proteins, was used to search the TIGR Comprehensive Microbial Resource (CMR) with the PhoP consensus sequence. This search brought up PhoP proteins and confirmed the specificity of the consensus sequence. A gapped BLAST search (Ancuta et al., 1996) of the SchuS4 and LVS genomes with the consensus sequence identified candidate phoP genes. A putative phoP homologue was identified with 26% identical deduced amino acid sequences and shown to have motifs consistent with response regulator proteins, containing both a response regulator receiver domain and a transcriptional regulatory protein (effector) domain. Nearly identical coding sequences were identified in both the SchuS4 (FTT1557c) and in LVS (FTL0552) genomic databases.

Construction of pPVNot/Erm

A plasmid derivative of pPV was constructed that has an added NotI restriction site and has erythromycin resistance (ErmR) substituted for chloramphenicol resistance (CmR). To accomplish this task, pPV shuttle vector (CmRApR) was kindly supplied by Drs. I. Golovliov and Anders Sjöstedt (Golovliov et al., 2003b). This plasmid was used to transform an Escherichia coli DH5α recipient to chloramphenicol resistance. pPV DNA was prepared from an E. coli DH5α trans-formant, and subsequently altered to introduce a NotI cloning site. The pPV vector has unique SalI and XbaI cloning sites. An adaptor was designed that could be ligated to SalI- and XbaI-cleaved pPV DNA to generate a NotI site. Oligonucleotides P327 and P328 were annealed to produce adaptors (Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com), and were ligated into pPV that had been cleaved with both SalI and XbaI and transformed into E. coli DH5α with selection for chloramphenicol resistance. The presence of the NotI site was confirmed by restriction analysis and the resulting plasmid designated pPVNot. This resulted in a mobilizable plasmid with unique NotI, SalI, and XbaI sites. A derivative of pPVNot was constructed that had the CmR marker replaced with ErmR. pPVNot was partially digested with HindIII, religated, and transformed into E. coli DH5α with selection for ampicillin resistance. Colonies were screened for the loss of chloramphenicol resistance and the loss of (only) the 3.2-kb HindIII fragment that carries CmR. This plasmid (ApR and CmS) was linearized by partial digestion with HindIII, and ligated to the ermC gene from pKS65. pKS65, the source of ermC, was generously provided by Dr. Joseph Dillard (Hamilton et al., 2001) (University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, WI). Transformants were scored for both ampicillin and erythromycin resistance on LB agar plates containing 200 μg/mL erythromycin and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. The resulting plasmid was designated pPVNot/Erm, and this plasmid was used for gene transfer into F. tularensis LVS.

Construction of the pPV-FTL0552 knockout plasmid

A modified version of a previously described method using PCR products to generate a knockout plasmid was used (Lauriano et al., 2003; Song et al., 2005). The flanking sequence consisting of approximately 700-bp upstream and 700-bp downstream of FTL0552 was amplified from F. tularensis LVS genomic DNA in two separate PCR reactions, using EasyStart 100 prealiquoted PCR reagents (Molecular BioProducts, San Diego, CA). The primer sequences for the 5′ flanking regions were Left-F and Left-R, and the primer sequences for the 3′ flanking sequences were Right-F and Right-R (Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com). A third PCR product consisted of the kanamycin resistance gene and promoter region that was amplified from pBBR1MCS2 (Kovach et al., 1995), using primers Kan-F and Kan-R. All three products were gel-purified using Geneclean Turbo (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and were used as templates in a PCR reaction to generate a single product with upstream and downstream flanking regions of FTL0552 and coding region from nucleotides 26–645 was replaced with kanR. This PCR product was generated using primers Left-F and Right-R and is flanked by NotI restriction sites. The entire PCR product was 2349 bp in length. The resulting PCR product was cleaved with NotI and ligated into the NotI site of pPVNot/Erm and transformed into E. coli JM109. Plasmid DNA was prepared with the GenElute HP Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The plasmid construct was confirmed by digestion with NotI and then transformed into E. coli S17-1.

The plasmid used for transcomplementation studies originated from pKK214 (Abd et al., 2003; Mohapatra et al., 2007). Briefly, the FTL0552 gene was amplified with primers 0552+RBS for and 0552 + RBS rev (Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com), which amplifies a 702-bp fragment of FLT0552 (genome sequence 534301–535003), including the ribosome binding site (RBS). This fragment was cloned into the XbaI and PstI sites of pKK214, immediately downstream of the F. tularensis groEL promoter. The resulting plasmid was transformed into the F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant to restore expression of the FTL0552 gene.

Delivery of FTL0552:kanR into F. tularensis LVS

A previously described strategy for allelic replacement was used (Golovliov et al., 2003b). The resulting plasmid with the FTL0552 coding sequence interrupted by the kanR gene was introduced into E. coli S17-1 for mobilization and transfer to LVS. Conjugation and selection were performed on supplemented GC agar plates containing 100 μg/mL polymyxin B and 25 μg/mL kanamycin. Isolated colonies were spotted on plates containing 5% sucrose, kanamycin (25 μg/mL), and polymyxin B (100 μg/mL) for counter selection with sacB. Colonies that were both kanamycin and sucrose resistant were verified by PCR and used for further analysis.

RNA extraction

RNA was isolated from Mueller Hinton broth cultures of F. tularensis LVS parental strain and FTL0552 mutant grown to log phase (OD550 of 0.600). For RT-PCR experiments, RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The aqueous phase was used in the RNeasy clean-up protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with a 15-min DNase digestion step (Qiagen) (Brotcke et al., 2006). The concentration of the RNA was assessed at OD260 and OD280, and the integrity of the 23S and 16S rRNA was verified on a 0.7% agarose gel.

RT-PCR analysis of FTL0552 and downstream genes

Primers were designed for the first and fourth genes immediately downstream of FTL0552 (Fig. 1). RT-PCR was performed using the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). Primers FTL0552-F and FTL0552-R (specific for FTL0552), primers lepB-F and lepB-R (specific for lepB), primers rnr-F and rnr-R (specific for rnr), and primers mutS-F and mutS-R (specific for the reference house keeping gene mutS) were used to reverse transcribe and amplify the cDNA synthesized from RNA isolated from both the F. tularensis LVS parental strain and the FTL0552 mutant. The products' sizes are 352 bp for FTL0552, 288 bp for lepB, 314 bp for rnr, and 304 bp for mutS. The conditions for reverse transcription and amplification were 50°C for 30min and 95°C for 15min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min, then a final elongation step of 72°C for 10min. For each primer set, reactions lacking the reverse transcription step were performed to detect DNA contamination. PCR products were run on a 1.0% agarose gel.

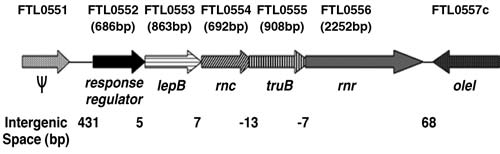

FIG. 1.

Arrangement of FTL0552 and adjacent genes on the F. tularensis LVS genome (NC007880). The genome locus tags are indicated as the size of the genes in base pairs (top) and the intergenic space between genes (below). The genes indicated are (as annotated on the genome sequence) Ψ; pseudogene; putative response regulator, lepB; signal peptidase I, rnc; RNase III, truB; tRNA pseudouridine synthetase B, rnr; RNaseR, and oleI; delta9 acyl-lipid fatty acid desaturase. The gene arrangement is suggestive of a five-gene operon transcribed from a promoter region upstream of FTL0552.

Intracellular survival assay

The method for assessing intracellular growth of F. tularensis LVS in macrophages was performed with minor modifications of the method previously described by Golovliov et al. (1997). J774A.1 mouse macrophage cells suspended in DMEM (DMEM, 10% FBS, and 4.5 g/mL glucose and L-glutamine) were seeded into a 24-well tissue culture plate at a density of 6 × 104cells/well and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. F. tularensis LVS parental, FTL0552 mutant, and the transcomplemented FTL0552 mutant strains were suspended in DMEM, added to each well at an MOI of 100, and allowed to infect for 2h at 37°Cin 5%CO2. Following infection, the cells were washed twice with PBS to remove extracellular bacteria. Gentamicin (50 μg/mL) was added to the wells, and the incubation was allowed to continue for 1 h. Thereafter, the cells were washed once with PBS, and media containing gentamicin (2 μg/mL) was added to the wells. At various time points (0, 24, 48, and 72 h), the cells were washed with PBS and lysed with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate. Viable counts were performed by plating serial 10-fold dilutions of the lysates on supplemented GC agar plates and incubating at 37°C (Golovliov et al., 1997). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data are representative of three independent experiments. Infection of PECs was performed with modifications of the method described by Twine et al. (2005). Peritoneal cells (PCs) were collected from thioglycolate-treated BALB/c mice, washed, and resuspended in RPMI-1640 (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) media containing 10% FBS, 50 μM2-mercaptoethanol, and L-glutamine. PC suspensions were seeded into a 96-well tissue culture plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. F. tularensis LVS and FTL0552 mutant bacteria were added to each well at an MOI of 50 and allowed to infect for 1.5 h. The cells were then washed twice with HBSS to remove extracellular bacteria. Medium containing gentamicin (50 μg/mL) was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h. Thereafter, the cells were washed once with HBSS and cultured in medium containing gentamicin (2 μg/mL). At various time points (0, 12, 24, and 48 h), the cells were washed with HBSS and lysed with 0.1% saponin. Viable counts were performed by plating serial 10-fold dilutions of the lysates on supplemented GC agar plates and incubating at 37°C (Golovliov et al., 2003). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Murine alveolar macrophage (MH-S) cell line was infected with F. tularensis LVS or FTL0552 mutant strain at an MOI of 100:1 for 2 h. The cells were then washed and treated with gentamicin (50 μg/mL) for 2 h to kill all the extracellular bacteria. The infected cells were lysed at 4, 24, and 48 h postinfection with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and plated on chocolate agar plates to quantitate the bacteria. The results are expressed as CFU/mL, and the statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA.

Fluorescence microscopy

FTL0552 mutant was stained with PKH67 green fluorescent cell linker mini kit (Sigma) as per the manufacturer's instructions. LVS transformed with a GFP-containing plasmid was used a control. About 1 × 104 MH-S (murine alveolar macrophage cell line) cells in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) were seeded on a sterile Lab-Tek chamber slide (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) and incubated for 12 h at 37°C. The cells were infected with the labeled FTL0552 or the GFP-LVS at an MOI of 100 and incubated at 37°C for 15, 30, and 45 min. Uninfected cells served as controls. After each indicated time, the cells were washed twice with sterile PBS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The MH-S cells were counterstained with PKH26 red fluorescence cell linker mini kit (Sigma) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were washed, mounted with the coverslips, and observed under a fluorescent microscope. For confocal microscopy, 0.5-μm Z sectioning was performed on a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Laser Scanning System, Biocompare, San Francisco, CA). The slides were observed under a C-Apochromat objective at 40 × magnification with 1.2 W corrections and visualized in channel-1 at 500–550 IR and channel-2 at 565–615 IR. The images were analyzed using LSM5 image browser software version 3.2.0.115 (Carl Zeiss, Biocompare).

Mouse infection

Six- to eight-week-old BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) of either sex were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment in the Animal Resource Facility at Albany Medical College and used for screening of the FTL0552 mutant. A frozen aliquot of F. tularensis LVS or F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant was thawed and diluted in sterile PBS. Prior to intranasal (i.n.) inoculation, the mice were deeply anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of ketamine (20 mg/mL) and xylazine (1 mg/mL). The mice (n = 10 for each group) were infected intranasally with 1 × 104 or 1 × 105 CFU of LVS or FTL0552 mutant in a volume of 20 μL PBS (10 μL per nare). The mice were monitored closely for morbidity and mortality for a period of 21–30 days postinfection, and the median survival time (MST) was calculated for each group of mice. Mice that survived the initial infection dose of 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant were challenged with 1 × 102 CFU of the virulent F. tularensis SchuS4 strain. All mice that survived 1 × 104 CFU of FTL0552 mutant were boosted with 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant and challenged 30 days later with 1 × 102 CFU of SchuS4. Actual numbers of bacteria were determined by plating the inoculum after primary infection and challenge. All the SchuS4 challenge experiments were carried out in the ABSL-3 facility of the Albany Medical College following standard operating procedures. All experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

A time course experiment was conducted to determine the kinetics of bacterial clearance. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 103 CFU of either LVS or FTL0552 mutant. A group of four mice each was sacrificed at days 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinfection. Lung, liver, and spleen were collected aseptically for quantitation of bacterial burden and histology at the indicated times.

Quantification of F. tularensis burden

Bacterial burdens were quantified in the lungs, livers, and spleens of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. The lungs from the infected mice were inflated with sterile PBS and collected aseptically in PBS containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Livers and spleens were also collected in a similar fashion. The organs were subjected to mechanical homogenization using a Mini-BeadBeater-8™ (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). The tissue homogenates were spun briefly at 1000 g for 10 s in a microcentrifuge to pellet the tissue debris. Supernatants were diluted 10-fold in sterile PBS, and 10 μL of each dilution was spotted onto chocolate agar plates in duplicate and incubated at 37°C for 2–3 days. The number of colonies on the plates were counted and expressed as CFU/gram of tissue. The remaining tissue homogenates were spun at 14,000 g for 20 min, and the clarified supernatants were stored at −20°C and used for measurement of tissue cytokine levels.

Histopathology

The lungs, livers, and spleens from infected mice were excised at days 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinfection and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin. Lungs were inflated via instillation of PBS into the trachea prior to fixation. Tissues were processed using standard histological procedures, and 5-μm paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylineosin and examined by light microscopy.

Cytokine measurement

Mouse Inflammation Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Kits (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA) were used for the simultaneous measurement of multiple cytokines in lung homogenates of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice infected either with LVS or FTL0552 mutant. Data were acquired on a FACSArray (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using CBA software version 1.1.

Gene microarray analysis

LVS parental strain and LVS FTL0552 mutant bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in MH broth cultures to log phase (OD600 of 0.60). RNA was extracted using the Enzymatic Lysis and Proteinase K Digestion of Bacteria protocol from the RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent Handbook (Qiagen), followed by purification using the RNeasy Mini Kit Purification of Total RNA from Bacterial Lysate protocol (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA in a standard reverse transcription reaction using 5 μg of random hexamers (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and Superscript III (Invitrogen). Amino allyl dUTPs were incorporated at this step (2.5 mM dATP, 2.5 mM dCTP, 2.5 mM dGTP, 1 mM amino allyl dUTP, and 1.5 mM dTTP) (Invitrogen). cDNA was purified using Zymo DNA purification columns as specified by the manufacturer (Zymo Research, Orange, CA), and samples were labeled with Cy5 (red) fluorophores and the reference was labeled with Cy3 (green) fluorophores (Amersham Biosciences). Unincorporated fluorophores were quenched using 5 μL of 4 M hydroxylamine and incubated in the dark for 15 min. The samples were then combined, and unincorporated dyes were removed using Zymo DNA purification columns. For hybridization, cDNA was eluted in 19 μL of Tris-EDTA buffer, and 2 μL of 20 mg/mL yeast tRNA (Invitrogen), 4.25 μL of 20 × SSC, and 0.75 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate were added to the probe. Probes were denatured for 2 min at 99°C, spun at 17,900 g, and cooled at room temperature before they were added to the arrays, prepared by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories Gene Microarray Lab (Brotcke et al., 2006). The samples and arrays were incubated at 60°C for ∼ 14 h, and stringency washes were performed. Briefly, the arrays were washed for 2 min each in a series of four washes with increasing stringency: (i) 2×SSC−0.03% sodium dodecyl sulfate, (ii) 2×SSC, (iii) 1×SSC, and (iv) 0.2×SSC. The microarrays were scanned and analyzed using a Gene Pix 4000A scanner and GENEPIX5.1 software (both from Axon Instruments, Redwood City, CA). Normalized data were collected using the Stanford Microarray Database. Spots were excluded from analysis due to obvious abnormalities, a regression correlation of < 0.6, or a Cy3 net mean intensity of < 100. Only spots with at least 70% good data across the experiment were included for analysis. The ratios of the red channels to green channels for each spot were expressed as log2 (red/green) and used for hierarchical clustering using the CLUSTER program. Results were visualized using the TREEVIEW program. Using data from all of the microarrays, significant differences between the wild type and mutant were determined using the Significance Analysis for Microarrays (SAM) program, v. 1.21. Using the two-class statistical analysis tool in the SAM program, a list of genes whose transcript levels were significantly increased or decreased between the two groups was calculated. A calculated false discovery rate of < 1% was used to assign significance, and a twofold cutoff in the change in expression level was imposed.

Statistical analyses

The survival results are expressed as Kaplan–Meier curves, and p values were determined using a Log-Rank test. All other results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and comparisons between the groups were made using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's correction, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test, or Student's t-test. Differences between the experimental groups were considered significant at p < 0.05 level.

Results

Identification of the response regulator gene

A putative response regulator in the F. tularensis LVS genome was identified by homology with a consensus PhoP amino acid sequence derived from alignment of the deduced peptide sequence from other gram-negative bacteria. The FTL0552 locus from the F. tularensis LVS genome sequence was identified and shown to have motifs consistent with response regulator proteins, containing both a response regulator receiver domain and a transcriptional regulatory protein domain. The locus is annotated as a two-component response regulator; however, no sensor histidine kinase gene can be identified in the area immediately upstream or downstream of this gene (Fig. 1). Recent studies identified 16 genes in Francisella spp. involved in environmental signal transduction and only 4 appear to share homology with known TCS sensor histidine kinases or response regulators. None of the TCS genes appear to be paired in the genome as typical TCS operons in other gram-negative bacteria (Mohapatra et al., 2007). Although the locus was identified by homology with a derived PhoP consensus sequence from gram-negative bacteria, FTL0552 also shares homology with other response regulator proteins. FTL0552 (FTT1557c) shares about 44% homology with PmrA of Salmonella and appears to be the equivalent to pmrA identified in F. tularensis subsp. novicida (Mohapatra et al., 2007). The gene arrangement of adjacent genes and the deduced amino acid sequence homology of this putative response regulator gene are highly conserved between LVS and the virulent F. tularensis SchuS4 strain (locus FTT1557c shows only one conservative amino acid change in residues 21–228). The putative response regulator gene (FTL0552) is the first gene in a series of five that appear to form a single operon with minimal intergenic spaces or in some cases overlapping genes (Fig. 1). RT-PCR revealed that FTL0552 and the four downstream genes are transcribed as one complete transcript, suggesting that FTL0552 is the first gene of a five-gene operon, transcribed from the same promoter (data not shown).

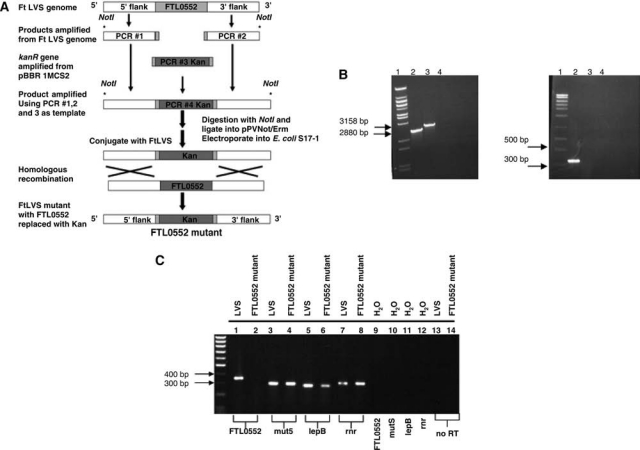

Mutation of F. tularensis LVS FTL0552

F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 knockouts were created by interrupting the FTL0552 gene by allelic replacement with a kanR cassette (Fig. 2A). F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 knockouts were confirmed by PCR using primers specific to FTL0552 and primers external to FTL0552 and the flanking region. To confirm recombination occurred at the target location within the chromosome, PCR was performed on colonies that were kanR and sucroseR using primers specific for the region flanking the area of recombination (FTL0552+1100-F and FTL0552 + 1100-R; Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com). The amplicon from this PCR reaction was the size predicted for recombination within the chromosome (3158 bp) but differed from the F. tularensis LVS parent strain PCR product (2880 bp), as expected (Fig. 2B). PCR of the same colonies using primers specific for a 315-bp region within the FTL0552 gene (FTL0552–F and FTL0552–R; Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com) revealed loss of the FTL0552 gene (Fig. 2B). Primers specific for the kanR gene were also used in PCR reactions to confirm incorporation of the kanR gene within F. tularensis LVS (data not shown). Sequencing of the 3158-bp PCR product amplified from F. tularensis LVS FTL0552::kanR revealed that nucleotides 26–645 of the FTL0552 gene (genome sequence 534341–534960) were deleted and replaced with the kanR gene.

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematic representation of the strategy used for generation of the FTL0552 deletion mutants. The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of FTL0552 gene were amplified from the F. tularensis LVS genomic DNA. The primers used for the amplification of the regions flanking the FTL0552 gene and kanamycin resistance gene (kanR) were designed with short overlapping sequences to the kanR gene derived from pBBR1MCS2 (28). The resulting three amplicons were gel-purified and used as template to amplify a PCR product with the kanR gene replacing FTL0552 (PCR product #4). This product was digested with NotI and ligated into the suicide plasmid pPVNot/Erm (see text). The resulting plasmid was introduced into F. tularensis LVS by transconjugation from E. coli. (B) Confirmation of FTL0552 knockout. Left gel photograph represents PCR of colonies after three passages on agar containing 5% sucrose. Primers are specific for the region flanking the region of recombination to confirm incorporation within the chromosome. Lane 1: Lambda BstE II DNA digest; lane 2: amplicon from LVS parent strain; lane 3: amplicon from potential FTL0552 mutant; lane 4: H2O control. Right gel photograph represents PCR of colonies after three passages on agar containing 5% sucrose. Primers are specific for a region within the FTL0552 gene to confirm loss of FTL0552. Lane 1: exACTGene midrange DNA ladder; lane 2: amplicon from LVS parent strain; lane 3: amplicon from potential FTL0552 mutant; lane 4: H2O control. (C) Deletion of FTL0552 gene does not effect transcription of downstream genes in the FTL0552 mutant. RT-PCR analysis of F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 and adjacent genes was performed to confirm loss of FTL0552 transcription in the F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant and to determine the effects on downstream genes. Lanes 1 and 2: amplicons using FTL0552-specific primers FTL0552-F and FTL0552-R; lanes 3 and 4: amplicons using mutS (house keeping gene)–specific primers mutS-F and mutS-R; lanes 5 and 6: amplicons using lepB-specific primers lepB-F and lepB-R; lanes 7 and 8: amplicons using rnr-specific primers rnr-F and rnr-R. F. tularensis LVS RNA was used for the reactions in lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 13. FTL0552-mutant RNA was used for the reaction in lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 14. Lanes 9–12 are water controls, and lanes 13 and 14 are no reverse transcription controls. All PCR products are run on a 1.0% agarose gel.

FTL0552 mutation appears to have little effect on downstream genes

RT-PCR was performed on RNA isolated from F. tularensis LVS and F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant using primers specific for FTL0552, lepB, and rnr (Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.liebertpub.com). The two genes, lepB and rnr, were selected to determine the effects of knocking out FTL0552 on transcription of downstream genes within the potential operon. The results confirmed that FTL0552 was not being transcribed in the mutant strain, while the two downstream genes examined were transcribed at levels similar to those seen in LVS (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the phenotype seen in the FTL0552 knockout mutant is not a result of polar effects but is directly attributed to the mutation in FTL0552 and ultimately to genes outside the putative operon regulated by FTL0552.

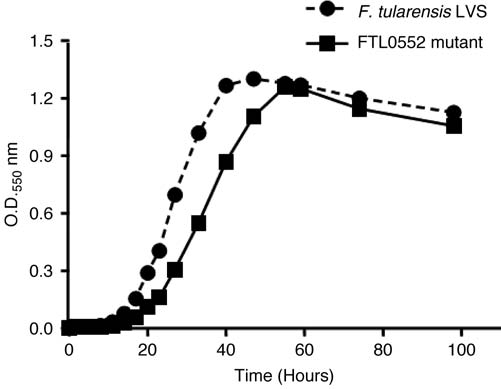

FTL0552 mutant is unable to replicate in mouse macrophages

A growth comparison between the LVS parental strain and the FTL0552 mutant was performed to assess the effects of knocking out the FTL0552 gene on the bacteria's ability to grow in an acellular environment. Isolated colonies of F. tularensis LVS were visible on supplemented GC agar plates in 24 h. In contrast, isolated colonies from the FTL0552 mutant were visible in 38–42 h. Overnight broth cultures were incubated at 37°C with aeration for a period of 4 days, and OD550 readings were measured at several time points during the course of growth. Growth of the FTL0552 mutant reached the same cell density as the parental strain of LVS, however, at a slightly slower rate (Fig. 3). The mutant reached stationary phase of growth about 6–8 h after the parental strain LVS.

FIG. 3.

FTL0552 mutant exhibits a growth defect under acellular growth conditions. The effect of FTL0552 gene deletion on growth under acellular conditions was assessed by growing the FTL0552 mutant and wild-type F. tularensis LVS in Mueller Hinton broth. Aliquots were removed at the times indicated, and the optical density was measured at 550 nm (OD550).

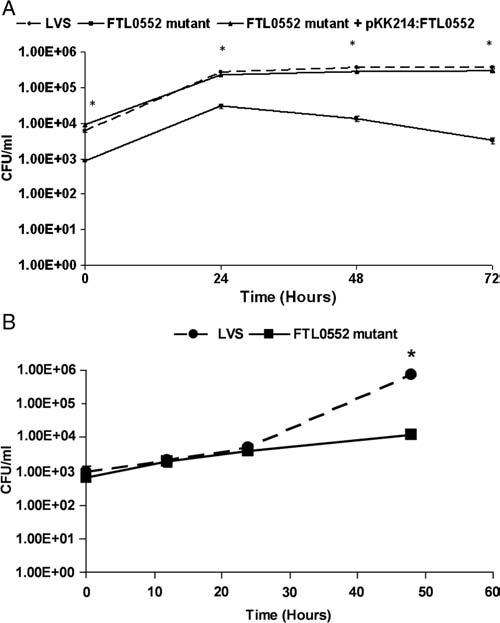

The ability of the mutant to invade and replicate within mouse macrophages was assessed using a gentamicin invasion assay. J774A.1 cells and mouse peritoneal macrophage cells were infected with the parental strain LVS or FTL0552 mutant LVS at an MOI of 100 for J774A.1 cells and an MOI of 50 for PCs for 2 and 1.5 h, respectively. At the indicated time points, viable counts were performed by lysing the cells and incubating serial dilutions of the sample suspensions on GC agar plates. Over a period of 72 h, F. tularensis LVS was able to invade and replicate within J774A.1 cells and bacterial numbers increased approximately 60-fold. However, significantly lower numbers of viable bacteria were recovered from J774A.1 cells infected with F. tularensis LVS FTL0552 mutant and increased only approximately threefold in 72 h (Fig. 4A). The ability of the transcomplemented mutant to invade and replicate within mouse macrophages was restored to levels similar to the parental strain LVS, suggesting the attenuation seen in macrophages is directly attributed to the loss of FTL0552 (Fig. 4A). Viable bacteria from PCs infected with the FTL0552 mutant were recovered but the numbers were significantly less than the parental strain (Fig. 4B). Over a period of 48 h, the mutant bacterial numbers increased <20-fold, compared to the parental strain bacterial numbers that increased >700-fold. An important factor contributing to the virulence and dissemination of F. tularensis within a host is its ability to invade and replicate within host macrophages. Mutation in FTL0552 appears to significantly alter the bacterium's ability to invade and replicate within mouse macrophage cells.

FIG. 4.

Intracellular survival assay. (A) Macrophage invasion assay of F. tularensis LVS, FTL0552 mutant, and FTL0552 mutant+pKK214:FTL0552. Murine macrophage J774A.1 cells were infected with F. tularensis LVS, FTL0552 mutant, and the complemented FLT0552 mutant at an MOI of 100. Bacteria were allowed to adhere to cells for 2 h and then treated with 50 μg/mL gentamicin to kill the extracellular bacteria. At the indicated time points, cells were lysed, serially diluted, and plated on GC agar plates to determine colony-forming units (CFUs). (B) Similar experiments were conducted using thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice infected at an MOI of 50 for 1.5 h. The results are expressed as CFU/mL and represent mean ± standard errors of the means of the CFU counts (n = 3 per time point). *p < 0.001 (using the Student's t-test).

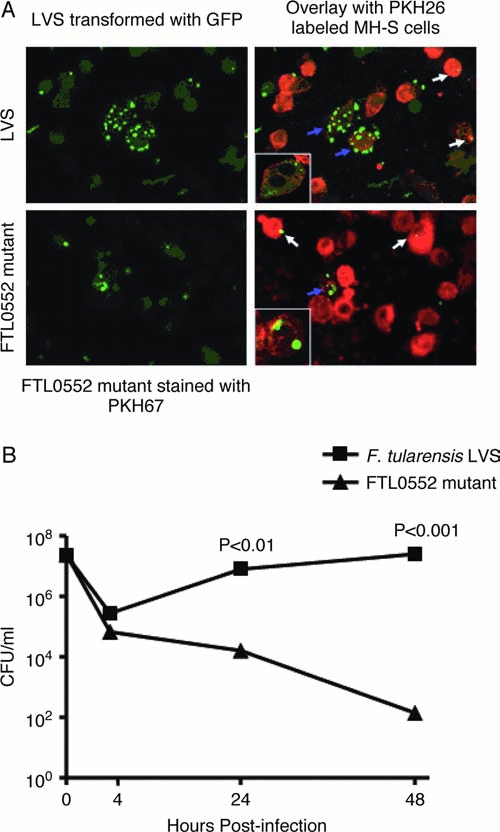

FTL0552 mutant is deficient for invasion in MH-S alveolar macrophages

The cell culture invasion assay with the J774A.1 cells and the elicited peritoneal macrophages has shown that the FTL0552 mutant is incapable of intracellular survival. We investigated further if this phenotype is due to the inability of FTL0552 to invade the macrophages. After 30 min of incubation with the labeled bacteria, we observed that majority of the MH-S cells infected with GFP-LVS harbored 2–10 bacteria per cell. On the contrary, cells infected with FTL0552 mutant contained very few bacteria (one to three bacteria per cell) (Fig. 5A). The results demonstrate that FTL0552 mutant is deficient for invasion in the macrophages. Confocal microscopy confirmed that bacteria stained green were localized inside the cells, whereas bacteria that took the counter stain and appeared yellow when the images were merged together were localized on the surface of the macrophages (Fig. 5A, insets). Using a gentamicin invasion assay, the ability of F. tularensis LVS or FTL0552 mutant strain to invade and replicate within MH-S cells was assessed. After infecting the cells for 2 h at an MOI of 100:1, followed by treatment with gentamicin, the infected cells were lysed at indicated times and the surviving bacteria quantified. The results suggest that less FTL0552 mutant bacteria are able to invade the MH-S cells, as compared to the parental strain, and there is a statistically significant difference in the amount of FTL0552 mutant bacteria that are able to survive/replicate within the MH-S cells (Fig. 5B). These results are in support of the confocal microscopy results, as well as the J774A.1 and PC gentamicin invasion assay results.

FIG. 5.

Macrophage invasion assays. (A) MH-S cells were infected using fluorescently labeled F. tularensis FTL0552 mutant and GFP-LVS. Blue arrows indicate the bacteria stained green are located inside the macrophages, whereas white arrows indicate bacteria stained yellow are present on the surface of the cell. The macrophages were counterstained with PKH26 red fluorescence dye (Sigma). Insets: Confocal images confirming the localization of the bacteria within the cells. (B) MH-S cells were infected with F. tularensis LVS or FTL0552 mutant strain at an MOI of 100:1 for 2h. The cells were then washed and treated with gentamycin (50 μg/mL) for 2 h to kill all the extracellular bacteria. The infected cells were lysed at indicated times with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and plated on chocolate agar plates to quantitate the bacteria. The results are expressed as CFU/mL, and the statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA.

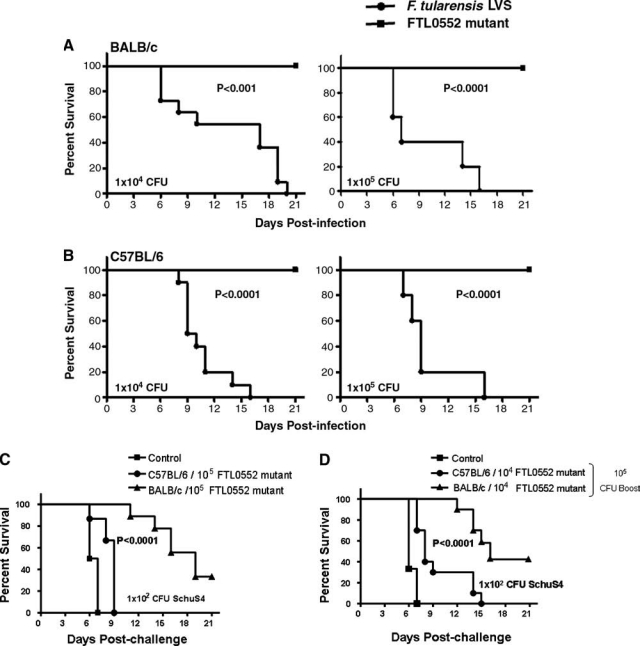

FTL0552 mutant is attenuated for virulence in mice

We screened the FTL0552 mutant in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice to assess the effect of the gene deletion on virulence. It was observed that all mice (n = 10) of both strains infected with 1×104 or 1×105 CFU of F. tularensis LVS succumbed by days 17–19 postinfection. In contrast, all BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice survived similar doses of FTL0552 mutant to at least day 21 postinfection (Fig. 6A, B). All mice that survived the primary infective dose of 1 × 105 of FTL0552 mutant were challenged with 1 × 102 CFU of SchuS4 strain. It was observed that C57BL/6 mice had a significantly extended MST of 9 days as compared to 6.5 days for the naive challenged mice. In the BALB/c mice challenged with SchuS4, the first death was recorded at day 12 postchallenge and 30% (3/10) of the mice survived the challenge dose out to at least 45 days (data not shown) postchallenge when the experiment was terminated (Fig. 6C). The C57BL/6 mice did not exhibit the protection afforded the BALB/c mice. The other groups of mice that survived initial infection with 1 × 104 CFU of FTL0552 were subsequently boosted with 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant and challenged with 1 × 102 CFU of SchuS4. Compared to mice that did not receive a booster (Fig. 6C), the MST for the C57BL/6 mice increased from about 9 to 16 days, 40% of the BALB/c mice survived until day 21 postchallenge, and the others had a significant delay in time to death (Fig. 6D). Thus, these results show that the FTL0552 mutant is not only highly attenuated for virulence in mice, but also retains its antigenic potential and provides partial protection against virulent SchuS4 challenge.

FIG. 6.

FTL0552 mutant is attenuated for virulence in mice and provides partial protection against lethal SchuS4 challenge. Survival of BALB/c (A) (n = 10) and C57BL/6 (B) (n = 10) mice infected intranasally with 1 × 104 or 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant or F. tularensis LVS. (C) Mice surviving 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant (n = 10) were challenged with 1 × 102 CFU of SchuS4. (D) Mice surviving 1 × 104 CFU of FTL0552 mutant (n = 10) were boosted with 1 × 105 CFU of FTL0552 mutant and challenged 30 days later with 1 × 102 CFU of F. tularensis SchuS4 strain. Untreated mice were kept as controls. Results are expressed as Kaplan–Meier curves, and p values determined using a Log-Rank test.

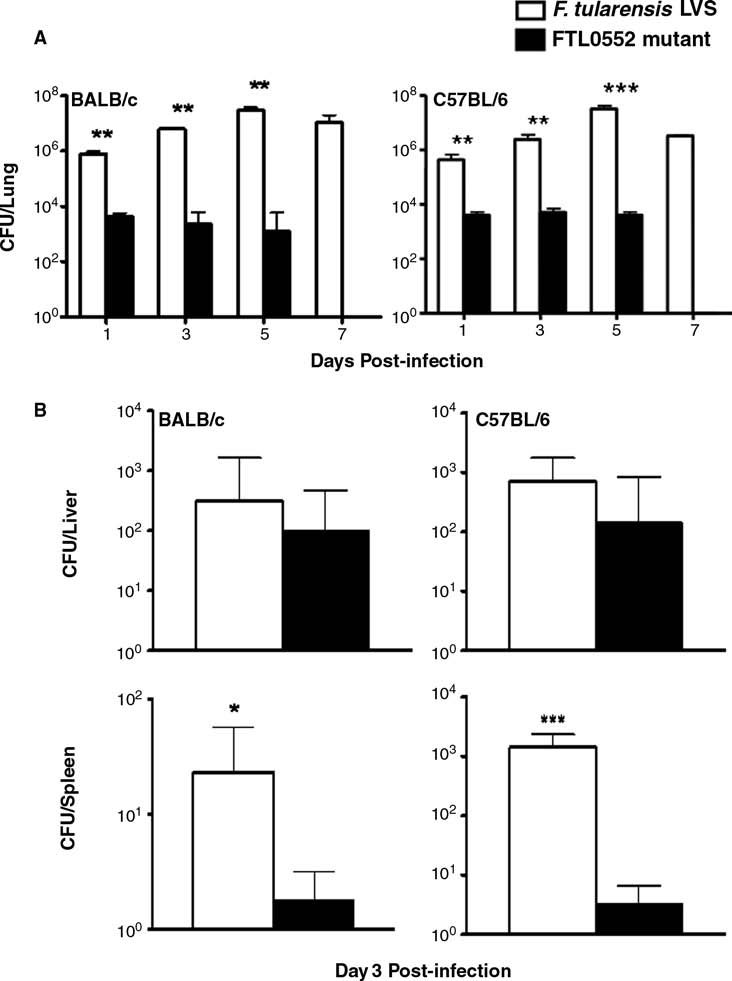

FTL0552 mutant exhibits markedly reduced systemic dissemination and is cleared rapidly

We further investigated the kinetics of clearance of the FTL0552 mutant in mice. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 103 CFU of either FTL0552 mutant or LVS. The mice were euthanatized at the indicated times, and bacterial numbers were quantitated in the lung, liver, and spleen. An identical pattern of bacterial kinetics was observed in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. At days 1, 3, and 5 postinfection, bacterial numbers were significantly lower in the lungs of FTL0552 mutant–infected mice compared to LVS-infected mice, and at day 7 postinfection, bacteria were completely eliminated from the lungs of FTL0552 mutant–infected mice (Fig. 7A). At day 3 postinfection, no significant differences were observed in bacterial numbers in LVS- or FTL0552 mutant–infected mice in the liver, but at subsequent time points, no bacteria were detected in FTL0552 mutant–infected mice. Significantly lower numbers of FTL0552 mutant bacteria disseminated to the spleen as compared to the liver, and no detectable bacteria were seen days 5 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 7B). These results corroborate attenuated virulence of FTL0552 mutant observed in mice and suggest that the attenuation of FTL0552 mutant may be due to the rapid clearance and significantly diminished dissemination.

FIG. 7.

FTL0552 mutant is rapidly cleared by BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. (A) BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intranasally with 5 × 103 CFU of FTL0552 mutant or F. tularensis LVS. Four mice were euthanatized at each indicated time point, and homogenates of the lungs were plated for the determination of bacterial burden. (B) Numbers of bacteria were quantified in the liver and spleen of the mice at day 3 postinfection. Results represent the mean ± standard errors of CFU counts (n = 4 per time point). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 (using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test).

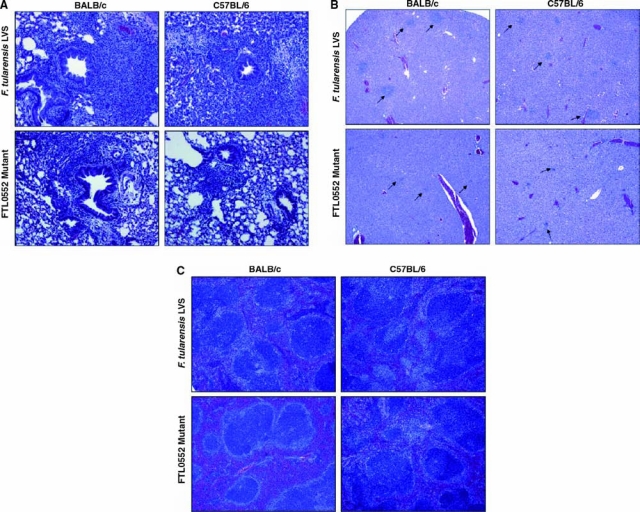

Infection with FTL0552 mutant induces less severe histological lesions

Extensive damage to vital organs is believed to be the primary cause of death from F. tularensis infection. We observed that the FTL0552 mutant is rapidly cleared; we further evaluated tissue sections from LVS- and FTL0552 mutant–infected mice to compare the degree of damage caused to the tissues by the two bacterial strains. Lesions in the lungs, livers, and spleens of FTL0552 mutant– and LVS-infected mice appeared as early as 3 days postinfection and subsequently became more extensive by days 5 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 8A). Lesions in the lungs of LVS-infected mice consisted mostly of multifocal bronchopneumonia and extensive lymphocytic to neutrophilic peribronchial and perivascular inflammation. However, these lesions were less severe and localized to very discrete areas in the lungs of FTL0552 mutant–infected mice (Fig. 8A). Livers from LVS-infected mice showed numerous multifocal neutrophilic to lymphocytic granulomas. These granulomas became larger as the infection progressed. On the contrary, few and very small granulomas were observed in the FTL0552 mutant–infected mice (Fig. 8B). Lesions in the spleen consisted of multifocal to coalescing areas of neutrophilic infiltration in the red pulp, enlargement of the marginal zones, and extensive proliferative responses in the germinal centers. However, the splenic tissue in FTL0552 mutant–infected mice appeared to be normal, and no inflammatory changes were observed (Fig. 8C). The results indicate that although the FTL0552 mutant is rapidly cleared from the tissues, it still induces a degree of inflammation and development of mild pathological lesions in the lungs and liver.

FIG. 8.

Mice infected with FTL0552 mutant exhibit markedly less severe histopathological lesions. Histopathological changes in the hematoxylineosin–stained sections of lungs (A), liver (B), and spleen (C) of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (n = 4) were evaluated at day 5 after i.n. inoculation with 5 × 103 CFU of FTL0552 mutant or F. tularensis LVS. Lung, liver, and spleen sections of sham-inoculated mice served as a control (magnification ×40). Arrows indicate granulomas that were observed to be smaller in mice infected with the FTL0552 mutant than those infected with LVS.

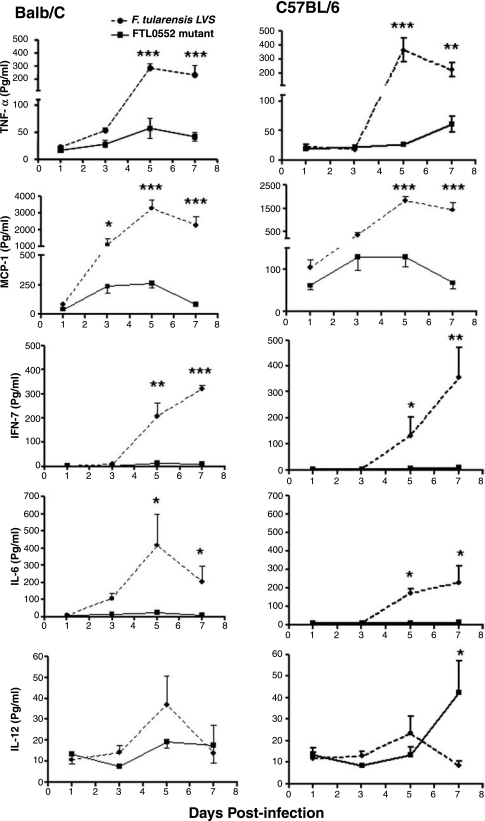

Mice infected with FTL0552 mutant produce lower levels of inflammatory cytokines

Unregulated production of cytokines in response to F. tularensis infection has been shown to be responsible for the severe histopathological lesions observed in the lungs, livers, and spleens of infected mice. We determined the levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1), and IL-12, in the lung homogenates of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice infected either with LVS or the FTL0552 mutant. LVS-infected mice had significantly elevated levels of all cytokines except IL-12 at days 5 and 7 postinfection (Fig. 9). The levels of IL-6 and IFN-γ in FTL0552 mutant–infected mice were below detection levels, whereas elevated levels of IL-12 were seen at day 7 postinfection. The results suggest that lowered cytokine production results in less severe pathology in the lungs of FTL0552 mutant–infected mice.

FIG. 9.

FTL0552 mutant exhibits lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Following i.n. inoculation of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice with 5 × 103 CFU of FTL0552 mutant or F. tularensis LVS, lung homogenates were prepared, and levels of proinflammatory cytokine were measured using Cytometric Bead Array (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Results represent the mean ± standard errors of the means of the cytokine concentrations (n = 4 mice per time point). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's correction).

FTL0552 regulates genes essential for intracellular survival and virulence

Gene microarray analysis revealed 148 genes regulated by FTL0552 (Supplemental Table 2, available online at www.liebertpub.com). The genes are identified by a fourfold or greater difference between F. tularensis LVS parent strain and FTL0552 mutant. The majority (75%) of the genes regulated are downregulated in the FTL0552 mutant, indicating they are FTL0552-activated genes. Among the genes downregulated by the mutant are the intracellular growth loci (iglA, iglB, iglC, and iglD) (Supplemental Table 2, available online at www.liebertpub.com). These genes are located in the FPI and have been shown to be essential for intracellular survival (Golovliov et al., 1997; Lauriano et al., 2004; Nano et al., 2004; McLendon et al., 2006). Other downregulated genes include a macrophage infectivity potentiator fragment; the gene encoding a type IV pili fiber building block protein, ampC; fopA; and, interestingly, the superoxide dismutase gene, sodB. The type IV pili fiber building block protein is involved in bacterial attachment and invasion of host cells. Citrobacter freundii AmpC is a cytoplasmic membrane protein gene required for induction of β-lactamase and was recently identified as a permease required for recycling of murein tripeptide and uptake of anhydro-muropeptides, which are produced by turnover of the cell wall during logarithmic growth of E. coli K-12 (Cheng and Park, 2002). FopA is an outer membrane protein specific to F. tularensis and is used as the target gene to rapidly detect and distinguish F. tularensis from Francisella philomiragia and other bacteria by LightCycler PCR (Fujita et al., 2006). The sodB gene in F. tularensis LVS encodes a functional FeSOD protein essential for bacterial survival under conditions of oxidative stress. A sodB mutant was attenuated for virulence in mice, indicating that FeSOD plays a role in virulence of F. tularensis LVS (Bakshi et al., 2006). The genes that are upregulated in the FTL0552 mutant include several hypothetical proteins, and pseudogenes, two transposases, and the gene encoding a type IV pili nucleotide-binding protein, pilT.

Discussion

It was the goal of this project to identify genes encoding potential two-component regulatory systems in F. tularensis that may be involved in regulation of virulence factor genes. In order to identify potential response regulator genes that activate genes necessary for bacterial virulence, we searched the F. tularensis LVS genome using a consensus amino acid sequence derived from the phoP response regulator genes from other gram-negative bacteria. One locus, FTL0552, was identified by the similarity of its protein product to the PhoP response regulator consensus sequence. The FTL0552 locus is 687 nucleotides in length and was annotated in the genome sequence as a transcriptional response regulator. The corresponding locus in F. tularensis SchuS4 (FTT1557c) is highly conserved.

In this report we describe the construction of a deletion mutant for FTL0552 in F. tularensis LVS. The FTL0552 gene was interrupted with a kanR gene, replacing nucleotides 26–645. A knockout mutant in the response regulator gene (FTL0552) was constructed by combining PCR-generated products delivered by conjugation, with subsequent recombination into the bacterial chromosome by allelic replacement. F. tularensis LVS mutant deleted for FTL0552 was shown to be defective for survival in both mouse J774A.1 cells and peritoneal macrophages. This mutant was completely attenuated in both BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice at doses up to 1 × 105 CFU, and was able to provide some protection against challenge with the virulent SchuS4 strain. Further, mice infected with the FTL0552 mutant exhibited reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokine production, and reduced evidence of histopathology in affected tissues, and, correspondingly, reduced systemic infection and rapid clearance of the bacterium. Our results support a major role for the FTL0552 gene product in controlling expression of virulence genes in F. tularensis.

Despite identification of the genomic locus (FTL0552) encoding this gene by homology with a PhoP consensus sequence from other bacteria, it does not appear to function as a PhoP homologue. While the poor intramacrophage survival and reduced virulence in mice are consistent with phoP mutants described in other bacteria (Groisman, 2001), the growth rate was not significantly altered at low Mg2+ concentrations (data not shown). Low Mg2+ environments have been reported to result in slower growth for Salmonella phoP mutants, as well as increased susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide, and acidic pH (Groisman, 2001; Tu et al., 2006). The F. tularensis FTL0552 mutant was not observed to exhibit either property (data not shown). This suggests that FTL0552 is not regulating genes involved in Mg2+ transport. Additionally, the absence of an adjacent gene on the F. tularensis genome sequence that is homologous to the sensor histidine kinase, phoQ, differs from the gene arrangement in other bacteria where phoP/phoQ forms a two-gene operon (Groisman, 2001). However, it is certainly possible that FTL0552 could form a two-component regulatory system with the product of an unknown gene located within another region of the F. tularensis chromosome. At this point, it is unclear if FTL0552 encodes a response regulator that is part of a two-component system.

FTL0552 protein is highly conserved among various Francisella strains, including F. tularensis subsp. holarctica OSU18 (NC008369), F. tularensis subsp. tularensis FSC 198 (NC008245), and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis SchuS4 (NC006570). When the deduced amino acid sequence derived from FTL0552 was used in a BLAST search against all peptide and translated sequences in GenBank, the best hits were known or putative response regulators. Included in these hits was PmrA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the response regulator part of the two-component regulatory system PmrA-PmrB. PmrA is activated through PmrB and responds to intracellular iron and mild acid pH and confers resistance to polymyxin B and other antimicrobial peptides in Salmonella (Kox et al., 2000; Wosten et al., 2000; Mohapatra et al., 2007). Functional PmrA is required to allow Salmonella to adapt to the toxic effects of high-iron environments (Wosten et al., 2000). Since PmrA mutants in other bacteria are typically more susceptible to polymyxin B, we might expect the FTL0552 mutant also to be more susceptible to polymyxin B (Wosten et al., 2000). However, the initial selection of our FTL0552 mutant was performed in the presence of 100 μg/mL of polymyxin B, and was resistant to polymyxin B up to a concentration of 1000 μg/mL. However, in Salmonella, PmrA-activated genes stimulated by growth in low magnesium require another two-component system, PhoP-PhoQ (Kox et al., 2000). In the presence of low magnesium, PhoP mediates transcription of the pmrD gene that mediates the transcriptional induction of PmrA-activated genes (Kox et al., 2000). In the presence of excess iron, transcriptional activation of PmrA-activated genes is independent of pmrD, which controls the activity of the PmrA-PmrB system at a posttranscriptional level (Kox et al., 2000). PhoQ serves as a magnesium sensor that modulates PhoP to activate the pmrD gene. The interaction between PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB in Salmonella is a novel type of interaction between a pair of two-component systems, affording the bacteria physiological plasticity in response to a broad spectrum of environmental conditions. Perhaps exposure to a high-iron or low-magnesium environment would render the FTL0552 mutant sensitive to polymyxin B. However, a mutant in this gene in F. tularensis subsp. novicida (FNU663.2) was found to be sensitive to antimicrobial killing by polymyxin B but apparently not through the typical mechanism of LPS modification (Mohapatra et al., 2007). This suggests that LVS FTL0552 and pmrA of F. tularensis subsp. novicida exhibit unique phenotypic properties, and the stimuli responsible for activating FTL0552 remains uncharacterized.

The gene encoding the FTL0552 response regulator appears to be present as the first gene of a cluster of five genes. The intergenic space between these genes is either extremely short or absent. Some of the genes overlap with the putative start codon for truB located inside the reading frame for rnc, and the start codon for rnr is inside the reading frame for truB. Thus, it is unlikely that promoter and transcription termination sequences for each or any of these five genes are located inside this putative operon. RT-PCR analysis revealed that FTL0552 is transcribed as a five-gene operon. The other genes included in this putative operon include signal peptidase I (lepB), ribonucleases (rnc and rnr), and tRNA pseudouridine synthetase B (truB). The five-gene arrangement is conserved in F. tularensis subsp. holarctica OSU18 (NC008369), F. tularensis subsp. tularensis FSC 198 (NC008245), and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis SchuS4 (NC006570). While it may be possible that some of these genes (the ribonucleases) are involved in some aspect of gene regulation, it appears that they encode proteins with diverse functions. This unusual cluster of genes is suggestive of some type of recombination event early in the evolution of Francisella spp.

It is interesting to note that our RT-PCR data (Fig. 2C) and microarray data indicate that mRNA levels for the genes downstream of FTL0552 in this putative operon are not significantly affected by insertion of the kanR gene into FTL0552 during construction of the mutant. There are two possible explanations for this observation: (1) the kanR gene promoter, which was introduced into the chromosome in the same direction as the putative operon, is driving transcription of downstream genes, or (2) the promoter for the operon is reading through FTL0552::kan into the downstream genes at levels similar to wild-type F. tularensis LVS. The later explanation seems more likely since the kanR gene is only slightly larger than FTL0552 and may have minimal polar effect on downstream genes. The kanR gene of pBBR1MCS2 that was used for gene replacement did not include 3′ flanking regions downstream of the coding region; thus, it is not likely that any transcription termination sequences were transferred. This explanation is further supported by studies that suggest that most exogenous promoters do not function well in F. tularensis; however, it would assume that the operon is not autoregulated by the FTL0552 gene product since it is absent in the FTL0552 mutant. Transcript mapping of the FTL0552 mutant mRNA would be required to definitively establish the origin(s) of transcription.

A hallmark of F. tularensis infection is the bacterium's ability to invade and replicate within host macrophages. Once adapted to the host target cells, the bacterium is able to vigorously multiply before the host can offer a protective immune response, and spread to various organs, such as the liver and spleen (Golovliov et al., 1997, 2003a). The host-derived response to the rapidly multiplying bacteria results in severe organ damage and is primarily responsible for the high mortality associated with F. tularensis LVS in mice and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (type A) in humans (Golovliov et al., 1997). Mutations in genes encoding bacterial proteins associated with intracellular growth have been shown to result in attenuation of F. tularensis LVS (Golovliov et al., 1997, 2003b). Our intracellular survival studies indicate that FTL0552 is critical to the bacteria's ability to invade and replicate within mouse macrophages. Complementation of the mutant further supports a role for FLT0552 in regulation of genes essential for the bacteria to survive and replicate in the complex environment of the host cell. These findings are corroborated by the mouse survival studies. The FTL0552 mutant is completely avirulent in the mouse model. When boosted, 40% of the BALB/c mice that had been infected with the FTL0552 mutant survived subsequent challenge with the highly virulent SchuS4 strain. Therefore, the FTL0552 mutant is not only highly attenuated in mice, but also retains its antigenic potential and provides partial protection against virulent SchuS4 challenge. However, we have not yet tested our transcomplemented mutant in the mouse model.

The mutant exhibited reduced dissemination and decreased ability to induce histopathology in the target organ tissues. Mice infected with the FTL0552 mutant were able to clear the bacteria much more efficiently than mice infected with the parental LVS strain. Significantly lower numbers of bacteria disseminated to the spleen and were completely cleared by day 5. After i.n. infection with the mutant strain, the mice were able to completely clear the bacteria from the lung by day 7. The efficiency of clearance correlated with the reduced histopathology evident in the lung, liver, and spleen of FTL0552 mutant–infected mice, with the spleen appearing normal and no inflammatory changes observed. Although some lesions and inflammation were observed in the liver and lung, there were very few, small lesions in these organs, which was dramatically different from the parental LVS strain–infected mice.

The mutant caused a reduced level of inflammatory cytokine production yet afforded partial protection to SchuS4 challenge. The low levels of acute phase inflammatory cytokines from the FTL0552-infected lungs correlated with the low level of organ damage seen. The increase in IL-12 indicates that a protective immune response was induced and is a very promising finding for developing a vaccine that is protective against F. tularensis. Of note, treatment of mice with IL-12 has previously been shown to induce significant protection against the lethal respiratory tularemia (Duckett et al., 2005).

In summary, we have described a strain of F. tularensis LVS that is deleted for FTL0552 encoding a putative response regulator. This mutant is defective for replication in macrophages and is avirulent in the mouse model. Although the phenotypic properties observed in the FTL0552 mutant are inconsistent with PhoP of other bacteria, it clearly plays a role in regulation of virulence genes in F. tularensis LVS. Perhaps as an orphan response regulator, FTL0552 works in trans with other regulatory proteins to exert its effect. Identification of a sensor histidine kinase responsible for the activation of FTL0552 could provide insight into the environmental signaling cues that modulate the activity of this gene. Two loci sharing homology with PhoQ (FTL1762 and FTL1878) were identified by searching the database with a derived PhoQ consensus sequence from other gram-negative bacteria. The genes are identified as a sensor histidine kinase (qseA) and a two-component sensor protein (kdpD). QseA is the quorum-sensing E. coli regulator A and KdpD is the sensor kinase in the two-component regulatory system, KdpD-KdpE, responsible for regulating intracellular K+ in E. coli. Recently, avirulent mutants in F. novicida homologues of both of these putative sensor kinase genes were isolated by negative selection using a mouse model (Weiss et al., 2007). Although most two-component sensor kinases are specific for activation of their cognate response regulator, it is possible that evolution has forced some bacteria to adapt by programming sensor kinases to respond to more than one environmental cue and act on more than one response regulator to exert a coordinated response for survival. This could explain the inconsistencies with the phenotypic properties of FTL0552 and the lack of a typical cognate sensor kinase. Identifying the environmental cues leading to activation of FTL0552 will provide insight into the protein interaction, leading to FTL0552 activation and modulation of virulence genes.

Currently, the data presented support the role of FTL0552 in regulation of virulence in F. tularensis LVS and provide an opportunity for investigation of the effects of an FTT1557c mutant in F. tularensis subsp. tularensis for evaluation as a possible vaccine candidate. Such a mutant may form the basis of a defined live attenuated vaccine that affords protection in humans against more-virulent type A strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Michelle Wyland-O'Brien for excellent technical support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI056320 and the Bay Pines Foundation. We thank Scott Bearden for providing the F. tularensis LVS stock culture, Robert Gilmore for suggestions regarding growth of LVS, Joseph Dillard for providing pKS65, Anders Sjöstedt for providing pPV, Prof. J.E. Mazurkiewicz for confocal microscopy, and Izabella Perkins and Cathy Newton for providing the mouse peritoneal macrophages. We thank John Gunn for providing pKK214.

References

- Abd H. Johansson T. Golovliov I. Sandstrom G. Forsman M. Survival and growth of Francisella tularensis in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(1):600–606. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.600-606.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancuta P. Pedron T. Girard R. Sandstrom G. Chaby R. Inability of the Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide to mimic or to antagonize the induction of cell activation by endotoxins. Infect Immun. 1996;64(6):2041–2046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2041-2046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony L.D. Burke R.D. Nano F.E. Growth of Francisella spp. in rodent macrophages. Infect Immun. 1991;59(9):3291–3296. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3291-3296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony L.S. Kongshavn P.A. Experimental murine tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis, live vaccine strain: a model of acquired cellular resistance. Microb Pathog. 1987;2(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi C.S. Malik M. Regan K. Melendez J.A. Metzger D.W. Pavlov V.M. Sellati T.J. Superoxide dismutase B gene (sodB)-deficient mutants of Francisella tularensis demonstrate hypersensitivity to oxidative stress and attenuated virulence. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(17):6443–6448. doi: 10.1128/JB.00266-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotcke A. Weiss D.S. Kim C.C. Chain P. Malfatti S. Garcia E. Monack D.M. Identification of MglA-regulated genes reveals novel virulence factors in Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun. 2006;74(12):6642–6655. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01250-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q. Park J.T. Substrate specificity of the AmpG permease required for recycling of cell wall anhydromuropeptides. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(23):6434–6436. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6434-6436.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J. Haeberli P. Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12(1 Pt 1):387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett N.S. Olmos S. Durrant D.M. Metzger D.W. Intranasal interleukin-12 treatment for protection against respiratory infection with the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Infect Immun. 2005;73(4):2306–2311. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2306-2311.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigelsbach H.T. Downs C.M. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J Immunol. 1961;87:415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D.F. Doolittle R.F. Progressive sequence alignment as a prerequisite to correct phylogenetic trees. J Mol Evol. 1987;25(4):351–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02603120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B.B. Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53(2):210–230. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.210-230.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B.B. Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61(2):136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman M. Sandstrom G. Sjostedt A. Analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of Francisella strains and utilization for determination of the phylogeny of the genus and for identification of strains by PCR. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44(1):38–46. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier A.H. Green S.J. Polsinelli T. Jones T.R. Crawford R.M. Leiby D.A. Elkins K.L. Meltzer M.S. Nacy C.A. Life and death of an intracellular pathogen: Francisella tularensis and the macrophage. Immunol Ser. 1994;60:349–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier A.H. Slayter M.V. Ziemba R. Meltzer M.S. Nacy C.A., et al. Live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis: infection and immunity in mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59(9):2922–2928. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2922-2928.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita O. Tatsumi M. Tanabayashi K. Yamada A. Development of a real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of Francisella tularensis. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59(1):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovliov I. Baranov V. Krocova Z. Kovarova H. Sjostedt A. An attenuated strain of the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis can escape the phagosome of monocytic cells. Infect Immun. 2003a;71(10):5940–5950. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5940-5950.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovliov I. Ericsson M. Sandstrom G. Tarnvik A. Sjostedt A. Identification of proteins of Francisella tularensis induced during growth in macrophages and cloning of the gene encoding a prominently induced 23-kilodalton protein. Infect Immun. 1997;65(6):2183–2189. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2183-2189.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovliov I. Sjostedt A. Mokrievich A. Pavlov V. A method for allelic replacement in Francisella tularensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003b;222(2):273–280. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield R.A. Drevets D.A. Machado L.J. Voskuhl G.W. Cornea P. Bronze M.S. Bacterial pathogens as biological weapons and agents of bioterrorism. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323(6):299–315. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman E.A. The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(6):1835–1842. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.1835-1842.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton H.L. Schwartz K.J. Dillard J.P. Insertion-duplication mutagenesis of neisseria: use in characterization of DNA transfer genes in the gonococcal genetic island. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(16):4718–4726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4718-4726.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel M. Holden D.W. Molecular genetic approaches for the study of virulence in both pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Microbiology. 1996;142(Pt 5):1049–1058. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis D.G. Weaver R.E. Steigerwalt A.G. Wenger J.D. Moss C.W. Brenner D.J. Francisella philomiragia comb. nov. (formerly Yersinia philomiragia) and Francisella tularensis biogroup novicida (formerly Francisella novicida) associated with human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(7):1601–1608. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1601-1608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.R. Newcombe J. Thorne S. Borde H.A. Eales-Reynolds L.J. Gorringe A.R. Funnell S.G. McFadden J.J. Generation and characterization of a PhoP homologue mutant of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(5):1345–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear S.M. Marques R.R. Carbonetti N.H. Differential regulation of Bvg-activated virulence factors plays a role in Bordetella pertussis pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 2001;69(4):1983–1993. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.1983-1993.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler L.A. Celli J. Finlay B.B. Pathogenic trickery: deception of host cell processes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(8):578–588. doi: 10.1038/35085062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach M.E. Elzer P.H. Hill D.S. Robertson G.T. Farris M.A. Roop R.M., 2nd Peterson K.M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166(1):175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kox L.F. Wosten M.M. Groisman E.A. A small protein that mediates the activation of a two-component system by another two-component system. EMBO J. 2000;19(8):1861–1872. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano C.M. Barker J.R. Nano F.E. Arulanandam B.P. Klose K.E. Allelic exchange in Francisella tularensis using PCR products. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano C.M. Barker J.R. Yoon S.S. Nano F.E. Arulanandam B.P. Hassett D.J. Klose K.E. MglA regulates transcription of virulence factors necessary for Francisella tularensis intraamoebae and intramacrophage survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(12):4246–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307690101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejona S. Aguirre A. Cabeza M.L. Garcia Vescovi E. Soncini F.C. Molecular characterization of the Mg2+-responsive PhoP-PhoQ regulon in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(21):6287–6294. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6287-6294.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T.M. Havig A. Casey M. Nano F.E. Frank D.W. Zahrt T.C. Construction and characterization of a highly efficient Francisella shuttle plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(12):7511–7519. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7511-7519.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrumb F.R. Aerosol infection of man with Pasteurella tularensis. Bacteriol Rev. 1961;25(3):262–267. doi: 10.1128/br.25.3.262-267.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]