Abstract

Purpose

Pre-clinical rheumatoid arthritis (RA) biomarker elevations were evaluated and utilized to develop a model for the prediction of time to future diagnosis of seropositive RA.

Methods

Stored samples from 73 military seropositive RA cases (and controls) from pre-RA diagnosis (mean 2.9 samples per case; samples collected a mean of 6.6 years prior-to-diagnosis) were tested for rheumatoid factor (RF) isotypes, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies, 14 cytokines/chemokines (bead-based assay) and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Results

Pre-clinical positivity of anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes was >96% specific for future RA. In pre-clinical RA, levels of the following were positive in a significantly greater proportion of RA cases versus controls: interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, fibroblast growth factor-2, Flt-3 ligand, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon gamma induced protein-10, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and CRP. Also, increasing numbers of elevated cytokines/chemokines were present in cases nearer to the time of diagnosis. RA cases ≥40 years-old at diagnosis had a higher proportion of samples positive for cytokines/chemokines 5-10 years prior-to-diagnosis, compared to cases <40 at diagnosis (p<0.01). In regression modeling using only case samples positive for autoantibodies highly specific for future RA, increasing numbers of cytokines/chemokines predicted decreased time-to-diagnosis, and the predicted time-to-diagnosis based on cytokines/chemokines was longer in older compared to younger cases.

Conclusions

Autoantibodies, cytokines/chemokines and CRP are elevated in the pre-clinical period of RA development. In pre-clinical autoantibody positive cases, the number of elevated cytokines/chemokines predicts the time of diagnosis of future RA in an age-dependent manner.

Keywords: pre-clinical rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, cytokines, chemokines, prediction model

Introduction

Multiple studies have demonstrated that disease-related biomarkers may be elevated prior to the onset of symptomatic rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These biomarkers include rheumatoid factor (RF) and antibodies to citrullinated protein antigens (ACPAs), as well as secretory phospholipase A2, multiple cytokines/chemokines, and variably C-reactive protein (CRP).(1-17) These findings suggest that there is a substantial “pre-clinical” period of RA, during which detectable immunologic and inflammatory changes are occurring that are related to disease development. As pre-clinical elevations of RA-related autoantibodies may be highly specific for future RA (7, 9), there is hope that these autoantibodies may be used to predict which currently asymptomatic individuals are at sufficiently high risk for future RA that they may be targeted with preventive therapies.

However, while RA-related autoantibodies are likely highly-predictive for future symptomatic disease, they may be present for many years prior to the onset of articular symptoms, and are therefore perhaps less useful in isolation for prediction of imminent symptomatic disease.(7, 9) As such, assessment of additional biomarkers in the pre-clinical period of RA may allow for the development of models that allow for accurate assessment of timing of onset of symptomatic disease. Additionally, as demonstrated by our prior findings (13), and those of Bos et al (18), that individuals with an older age-at-diagnosis of RA have a longer duration of pre-clinical autoantibody positivity, age-related duration of other pre-clinical elevations biomarkers may influence the development of models to predict the timing of onset of symptomatic future RA.

In this study we utilized stored pre-clinical samples from military RA cases to evaluate the following: 1) levels of autoantibodies, cytokines/chemokines and CRP during the pre-clinical phase of RA development, and their diagnostic accuracy for future disease, 2) age-related differences in timing of elevations of these biomarkers, and 3) biomarker testing to predict the timing of onset of symptomatic RA in subjects at high-risk for future disease.

Methods

Study population

Eighty-three subjects with RA were identified at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) Rheumatology Clinic. These subjects had been clinically evaluated between 1989 and 2003, had their date of diagnosis of RA established by chart review, and all had stored serum samples (290 pre- and post-diagnosis samples) available through the Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR). This repository was created to improve the health of the United States’ armed services, and serum samples are collected at enlistment, deployment and at regular intervals during military service, and stored at minus 30 degrees centigrade. Additionally, 83 military subjects without RA were identified in the DoDSR to serve as controls, matched to cases on age (case age-at-diagnosis), sex, race, number of samples available, duration of sample storage and enlistment region.

Selection of seropositive RA cases

Due to the specificity of autoantibodies for established and future RA demonstrated in prior studies (7, 9, 19, 20), and concerns that seronegative RA represents a disease distinct from seropositive RA (21), 73/83 (88%) of these military cases with seropositive RA were selected for analyses. Classification as seropositive RA was determined if a case met ≥1 of the following criteria: 1) post-RA diagnosis RF positivity by WRAMC testing (RF by nephelometry or latex agglutination)(N=67), and, 2) RF (ELISA for isotypes) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody positivity by our testing of post-diagnosis or immediate (<1 year) pre-diagnosis samples (N=6). All 73 seropositive RA cases met ≥4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 Revised Criteria for RA.(22)

Biomarker analysis

Autoantibody and CRP Testing

All samples were tested for: RF isotypes IgM, IgA and IgG (international units per milliliter [IU/mL]) using ELISA (QUANTA Lite™) kits to manufacturer’s specifications (INOVA Diagnostics, Inc, San Diego, California); anti-CCP was measured using anti-CCP2 ELISA assay (Diastat, Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Ltd., Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom [Units per milliliter [U/mL]). CRP was measured using a high-sensitivity nephelopmetric assay (BN II Nephelomter, Dade Behring, Deerfield, Illinois, USA) (reported in milligrams per liter (mg/L)).

Cytokine/Chemokine Testing

All samples were tested for 14 cytokines/chemokines: interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, eotaxin ( or CCL11), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), Flt-3 ligand, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon gamma induced protein-10 (IP-10)( or CXCL10), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (or CCL-2). Cytokines/chemokines were measured using bead-based 14-plex assay (Beadlyte kit, Upstate, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA) and the Luminex xMAP 200 System (Luminex, Austin, Texas, USA). Serum samples were thawed and incubated with cytokine-specific antibody-coupled beads, followed by incubation with indicator antibodies. After incubation, samples were read by the Luminex 200 System. Quantitative levels of cytokines/chemokines were determined by comparison to standard curves and were reported in picograms per milliliter (pcg/mL). Additionally, as RF may interfere with cytokine assays, Heteroblock™ reagent (Omega Biologicals Inc, Bozeman, MT) was used in all samples (3 micrograms/mL of serum) to minimize effect of RF.(23) Prior studies have shown that values of cytokines/chemokine levels from this bead-based assay are highly correlated with ELISA assays.(23, 24)

Dichotomous values for autoantibodies, cytokines/chemokins and CRP

Autoantibodies

As the 1987 ACR RA criteria specifies that a RF level is considered positive if present in <5% of control subjects (22), we established a dichotomous cut-off level for each of the RF assays that was positive in <5% of 491 blood donor controls, separate from the military. Anti-CCP was considered positive if greater than 5 U/ml (kit cut-off).

Cytokines/chemokines

A dichotomous cut-off for each cytokine/chemokine was determined using post-RA diagnosis serum samples within 2 years of diagnosis from military seropositive RA cases (N=42 samples available in this time period) and controls, and performing receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis to establish a cut-off for each cytokine/chemokine that was >90% specific for the diagnosis of RA.(25) This 2-year period was selected as it is likely to have elevated cytokines/chemokines due to temporal proximity to onset of symptomatic disease.

CRP

For CRP, two separate cut-offs for positivity were used: >5 mg/L and >10 mg/L.

Statistical Analyses

Proportions of biomarker positivity were compared between groups with chi-squared testing (Fisher’s Exact Testing when appropriate). Comparison of median counts of biomarkers between groups and pre-diagnosis time intervals were compared using Mann Whitney U analysis, as due to small numbers, non-parametric analysis was most conservative. Sensitivity/specificity calculations were performed using 2×2 table analyses comparing military RA cases with military controls as well as 200 blood donor controls (59% male, mean age 53 [standard deviation 15 years]). These latter controls were separate from the military, and separate from the 491 controls used for establishing RF cut-off values. Regression analysis with random subject terms for intercept and slope was used to determine the pre-diagnosis time of separation of cytokine/chemokine counts in cases versus controls, using a series of approximate t tests to compare cases and control mean regression values at incremented pre-diagnosis times.(26) Additionally, this analysis was controlled for multiple comparisons with a Scheffá adjusted critical value.(27) There was no significant difference in residuals distributions using Gaussian or Poisson modeling suggesting that assumption of a normal distribution in this analysis is sufficient. The duration of time (in years) from a pre-clinical sample with biomarker positivity to time of diagnosis was modeled using a mixed effects linear regression with a random intercept term and a backwards step-wise procedure, with final variables included in the model based on a likelihood ratio test. This approach additionally allowed for correlation of multiple measures within an individual. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical considerations

The study protocol and analyses were approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards at the WRAMC, the University of Colorado and Stanford University.

Results

Demographics and autoantibody testing (Tables 1, 2)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of military cases with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and controls *

| All Cases (N=83) | Seronegative Cases (N=10) |

Seropositive RA Cases (N=73) |

Controls (for seropositive cases) (N=73)** |

Cases <40 at diagnosis of RA (N=35) |

Cases ≥40 at diagnosis of RA (N=38) |

P- value+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age at diagnosis,

mean (SD)[range] |

39.9 (10.0)[20.9-66.1] | 39.1 (8.7)[26.4-53.5] | 40.0(10.3)[20.9-66.1] | 39.9 (10.3)[20.9-66.1] | 31.3 (5.6)[20.9-39.7] | 48.1 (6.2)[40.0-66.1] | <0.01 |

| Male | 49 (59.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 43 (58.9%) | 43 (58.9%) | 17 (48.6%) | 26 (68.4%) | 0.10 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 57 (68.7%) | 8 (80.0%) | 49 (67.1%) | 49 (67.1%) | 21 (60.0%) | 28 (73.7%) | 0.27 |

| Black | 21 (25.3%) | 2 (20.0%) | 19 (26.0%) | 19 (26.0%) | 10 (28.6%) | 9 (23.4%) | |

| Other*** | 5 (6.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 5 (6.9%) | 5 (6.9%) | 4 (11.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Erosions, N (%) | |||||||

| Present | 42 (50.6%) | 4 (40.0%) | 38 (52.0%) | n/a | 20 (57.1%) | 18 (47.4%) | 0.48 |

| Pre-Diagnosis Serum Samples (Total samples N=212) |

All Cases | Sero-Negative Cases |

Seropositive Cases | Controls (for seropositive cases) |

Cases <40 at diagnosis of RA (N=35) |

Cases ≥40 at diagnosis of RA (N=38) |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples per case Mean (SD) [range] |

3.5 (1.2)[1-5] | 3.6 (1.0)[2-5] | 3.5 (1.3)[1-5] | 3.5 (1.3)[1-5] | 3.7 (1.2)[1-5] | 3.2 (1.3)[1-5] | 0.10 |

| Pre-diagnosis samples per case Mean (SD) [range] |

2.9 (1.2)[1-4] | 3.1 (1.0)[1-4] | 2.9 (1.2)[1-4] | 2.9 (1.2)[1-4] | 3.0 (1.1)[1-4] | 2.8 (1.4)[1-4] | 0.41 |

| Time of first collection of samples pre-diagnosis ( in years) Mean (SD) [range] |

6.6 (3.7) [0.06 to 13.67] |

6.4 (2.7) [0.84 to 10.89] |

6.6 (3.9) [0.06 to 13.67] |

6.6 (3.9) [0.04 to 13.71] |

5.8 (3.5) [0.99-13.63] |

7.3 (4.1) [0.06-13.67] |

0.08 |

Sero-positive status indicates that subject met ≥1 of the following criteria: 1) RF positivity by WRAMC testing (RF only, nephelometry or latex agglutination), and/or 2) RF or anti-CCP positivity by testing of post- or immediate pre-diagnosis samples.

Controls were matched to cases by age, based on the age of a case at time of diagnosis of RA. For example, if a case was 40 at time of diagnosis of RA, the corresponding control would be the same age.

Other includes Asian, Native American, and multi-racial subjects

P-values are for comparisons between age-at-diagnosis groups <40, ≥40, using chi-squared or t-tests

Abbreviations: RA=rheumatoid arthritis; SD= standard deviation

Table 2.

Proportions of positivity, and sensitivity and specificity for future rheumatoid arthritis (RA) ofautoantibodies tested at any point in the pre-RA diagnosis period in sero-positive RA cases and controls

| Autoantibody | Case (N=73) | Controls (N=73) | Sensitivity | Specificity (compared to matched military controls) |

Specificity (compared to 200 random blood donor controls**) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CCP (>5 units/mL) * | 51 (69.9%) | 0 | 69.9% | 100% | 99.0% |

| RF-IgA (>10.5 units) | 40 (54.8%) | 3 (4.1%) | 54.8% | 95.9% | 98.0% |

| RF-IgG (>10.9 units) | 24 (32.9%) | 5 (6.8%) | 32.9% | 93.2% | 94.0% |

| RF-IgM (>13.6 units) | 41 (56.2%) | 3 (4.1%) | 56.2% | 95.9% | 94.0% |

| Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes | 54 (74.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 74.0% | 98.6% | 96.5% |

| Sensitivity, specificity of autoantibodies for future RA by pre-diagnosis time interval, and age-at-diagnosis*** |

Anti-CCP | RF-IgA | RF-IgG | RF-IgM | Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time interval ≥0 to ≤1 years prior to RA diagnosis | |||||

| Age-at-diagnosis <40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 77.8%, 100% | 72.2%, 100% | 22.2%, 100% | 55.6%, 100% | 83.3%, 100% |

| Age-at-diagnosis ≥40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 77.8%, 100% | 77.8%, 80.0% | 55.6%, 90.0% | 77.8%, 100% | 77.8%, 90.0% |

| Time interval >1 to ≤5 years prior to RA diagnosis | |||||

| Age-at-diagnosis <40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 61.3%, 100% | 32.3%, 96.8% | 16.1%, 93.6% | 32.3%, 100.0% | 64.5%, 100.0% |

| Age-at-diagnosis ≥40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 64.0%, 100% | 44.0%, 96.0% | 36.0%, 92.0% | 52.0%, 96.0% | 68.0%, 96.0% |

| Time interval >5 to ≤10 years prior to RA diagnosis | |||||

| Age-at-diagnosis <40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 17.6%, 100% | 17.6%, 100.0% | 11.8%, 100.0% | 17.6%, 100% | 23.5%, 100% |

| Age-at-diagnosis ≥40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 43.5%, 100% | 30.4%, 100.0% | 21.7%, 95.6% | 52.2%, 91.3% | 43.5%, 100% |

| Time interval ≥ 10 years prior to RA diagnosis | |||||

| Age-at-diagnosis <40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% |

| Age-at-diagnosis ≥40 Sensitivity, Specificity | 18.2%, 100% | 18.2%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 27.3%, 100.0% | 27.3%, 100% |

Of note, if the cut-off for anti-CCP positivity was lowered from >5 units to >2 units, sensitivity and specificity of positivity in any pre-clinical sample for future RA were 75.3% and 100%, respectively, compared to military controls, with a specificity of 96.5% when compared to 200 non-military blood donor controls.

These were random blood donors (N=200, mean age 53, 59% male – not significantly different than military population) and some may have had a diagnosis of RA. As such, specificity using this group as comparison may be underestimated.

Sensitivity, specificity for future RA were calculated in comparison to military controls

RF was also assessed by nephelometry, according to manufacturer’s specifications (Dade Behring, Newark, Delaware, USA), with a cut-off of ≥24.4 units positive yielding a sensitivity and specificity of pre-RA diagnosis positivity for future RA of 53.4 and 93.2%, respectively, when compared to military controls.

Abbreviations: anti-CCP=anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; RF=rheumatoid factor; Ig=immunoglobulin

Subject demographics are presented in Table 1. Anti-CCP positivity at any point pre-diagnosis was 69.6% sensitive for future seropositive RA, with a specificity of 100% compared to military controls, and 99% compared to 200 non-military blood donor controls (Table 2). Pre-diagnosis positivity for anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes (IgM, IgG, or IgA) was overall 74.0% sensitive and 98.6% specific for future seropositive RA compared to matched military controls, and 96.5% specific compared to blood donor controls, although sensitivity of autoantibodies for future disease increased closer to diagnosis (Table 2). The proportions of seropositive RA cases with pre-clinical autoantibody positivity (any type) did not significantly differ by age-at-diagnosis (<40, ≥40) (data not shown).

Cytokine/chemokine/CRP testing (Table 3, Figure 1)

Table 3.

Positivity of cytokines/chemokines and C-reactive protein in at least one sample at any time prior-to-diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and sensitivity and specificity for future sero-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in sero-positive RA cases (N=73) and matched controls*

| Biomarker | Cases, N (%) | Controls, N (%) | P-value | Sensitivity (%)** | Specificity (%)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eotaxin | 10 (13.7) | 12 (16.4) | 0.64 | 13.7 | 86.3 |

| FGF2 | 28 (38.4) | 12 (16.4) | <0.01 | 38.4 | 83.6 |

| FLT3-Ligand | 42 (57.5) | 29 (39.7) | 0.03 | 57.5 | 60.3 |

| GMCSF | 33 (45.2) | 15 (20.6) | <0.01 | 45.2 | 53.4 |

| IL1α | 39(53.4) | 26(35.6) | 0.03 | 53.4 | 64.4 |

| IL1β | 28 (38.4) | 15 (20.6) | 0.02 | 38.4 | 79.4 |

| IL6 | 25 (34.2) | 14 (19.2) | 0.04 | 34.2 | 80.8 |

| IL10 | 27 (37.0) | 11 (15.0) | <0.01 | 37.0 | 84.9 |

| IL12P40 | 41 (56.2) | 17 (23.3) | <0.01 | 56.2 | 76.7 |

| IL12P70 | 29 (39.7) | 17 (23.3) | 0.03 | 39.7 | 76.7 |

| IL15 | 31 (42.5) | 13 (17.8) | <0.01 | 42.5 | 82.2 |

| IP10 | 41 (56.2) | 25 (34.2) | 0.01 | 56.2 | 65.8 |

| MCP1 | 27 (37.0) | 24 (32.9) | 0.60 | 37.0 | 67.1 |

| TNFα | 33 (45.2) | 14 (19.2) | <0.01 | 45.2 | 80.8 |

| Sensitivity/Specificity of cytokine/chemokine counts in combination with autoantibodies (in any pre-RA diagnosis sample) for future seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (cases N=73) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | Cases, N (%) | Controls N (%) | P-value | Sensitivity(%)** | Specificity(%)** |

| >5 cytokines/chemokines (any type) | 29 (39.7) | 16 (21.9) | 0.02 | 39.7 | 78.1 |

| >10 cytokines/chemokines (any type) | 12 (16.4) | 3 (4.1) | 0.03 | 16.4 | 95.9 |

| Anti-CCP | 51 (69.9) | 0 (0) | <0.01 | 69.9 | 100 |

| Anti-CCP and/or >5 cytokines/chemokines | 57 (78.1) | 16 (21.9) | <0.01 | 78.1 | 78.1 |

| Anti-CCP and/or >10 cytokines/chemokines | 53 (72.6) | 3 (4.1) | <0.01 | 72.6 | 95.9 |

| Any sample with single RF isotype (any) positive | 11 (15.1) | 9 (12.3) | 0.81 | 15.1 | 87.7 |

| Single RF isotype and/or >5 cytokines/chemokines | 39 (53.4) | 21 (28.8) | <0.01 | 53.4 | 71.2 |

| Single RF isotype AND >5 cytokines/chemokines | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.5) | 0.34 | 1.4 | 94.5 |

| Single RF isotype and/or >10 cytokines/chemokines | 23 (31.5) | 10 (13.7) | 0.02 | 31.5 | 86.3 |

| Single RF isotype AND >10 cytokines/chemokines | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 0.5 | 0.0 | 97.3 |

| Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes | 54 (74.0) | 1 (1.4) | <0.01 | 74.0 | 98.6 |

| Anti-CCP and/or ≥ 2 RF isotypes and/or >5 cytokines/chemokines | 59 (80.8) | 17 (23.3) | <0.01 | 80.8 | 76.7 |

| Anti-CCP and/or ≥ 2 RF isotypes AND >5 cytokines/chemokines | 24 (32.9) | 0 (0) | <0.01 | 32.9 | 100 |

| Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes and/or >10 cytokines/chemokines | 55 (75.3) | 4 (5.5) | <0.01 | 74.3 | 94.5 |

| Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes AND >10 cytokines/chemokines | 11 (15.1) | 0 (0) | <0.01 | 15.1 | 100 |

Cases are individuals who developed seropositive RA (RF and/or anti-CCP positive); controls are military subjects without RA, matched to cases on age, race, gender and duration of serum sample storage.

Sensitivity/specificity for future seropositive RA, in case-control analysis

Abbreviations: RF=rheumatoid factor (isotypes IgG, IgM, IgA); anti-CCP= anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, Eotaxin ( or CCL11), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), Flt-3 ligand, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon gamma induced protein-10 (IP-10)( or CXCL10), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (or CCL-2); cytos/chemos=cytokines/chemokines

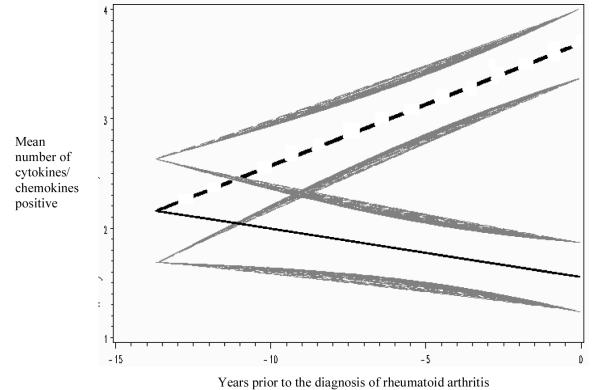

Figure 1. Mixed model regression lines of mean cytokine/chemokine counts in sero-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cases (N=73 with 212 pre-diagnosis samples) versus controls over time in the pre-clinical period of RA development.

The mean values for cases are represented by the straight dashed line, and controls are the straight solid line. The curved shaded lines represent standard errors of the mean for each regression line. In this mixed model analysis RA cases had significantly elevated cytokine/chemokine counts compared to controls ~7.2 years prior-to-diagnosis of RA.

CRP and all cytokines/chemokines, except eotaxin and MCP-1, were positive in at least one pre-diagnosis sample in significantly more cases than controls (Table 3). Between age-at-diagnosis groups (<40, ≥40), there were no differences in the proportion of cases with pre-diagnosis positivity for cytokines/chemokines (individual or counts) or CRP, with the exception that IL-10 was positive pre-diagnosis in 51.4% of cases <40 at diagnosis, versus 23.7% of cases ≥40 (p=0.02). In cases, the number of elevated pre-diagnosis cytokines/chemokines increased over time, becoming significantly elevated compared to controls ~7.2 years prior-to-diagnosis of RA (Figure 1). The sensitivity/specificity for future RA of pre-clinical cytokine/chemokine positivity combined with autoantibodies is presented in Table 3, and data regarding the diagnostic accuracy for future RA of cytokine/chemokine counts in seropositive and seronegative RA are included in on-line Supplemental Figures A and B. Of note, in the seronegative RA cases (N=10), there was a lower proportion of subjects with pre-clinical positivity for cytokines/chemokines when compared to seropositive cases (data not shown). Although not statistically significant, these results suggest that seronegative RA has less pre-diagnosis cytokine/chemokine elevations than seropositive RA. Also, in regression analyses (not shown), there was no association of individual cytokine/chemokine or CRP positivity with a specific autoantibody (any type).

Additionally, to determine if cytokine/chemokine positivity preceded autoantibody positivity, 58 samples collected a mean of 5.6 years prior-to-diagnosis were identified from 16 cases that were initially anti-CCP negative but would later develop pre-diagnosis anti-CCP positivity. In these samples, the cytokines IL-1α, IL-6, and IP-10 were positive in a higher proportion in cases than their controls prior to anti-CCP positivity (p<0.05, chi-squared testing). In 33 pre-anti-CCP positive samples from 12 cases that were also negative for RF isotype(s), IL-1α and IP-10 were still statistically-significantly elevated (p<0.05) in cases versus their controls.

Biomarker positivity by pre-diagnosis intervals and age-at-diagnosis

Overall, biomarkers were positive pre-clinically in greater proportions of subjects nearer the time of diagnosis (Table 4). For the time interval <10 to ≥5 years prior-to-diagnosis, the median cytokine/chemokine count in subjects ≥40 at diagnosis was greater when compared to those <40 at diagnosis (median counts 6.5 versus 3.0; p<0.01), while younger cases were more likely to have elevations immediately pre-diagnosis, indicating an age-related effect on cytokine/chemokine positivity in cases (Table 4). Additional data regarding proportions of cases with biomarker positivity by pre-diagnosis time interval and age group are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proportions of samples from seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cases (N=73) positive for biomarkers during defined pre-diagnosis time intervals, by age-at-diagnosis grouping*

| Age-at-diagnosis of RA <40 | Age-at-diagnosis of RA ≥40 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervals prior to diagnosis (in years) |

≥10 | <10≥5 | <5≥1 | <1≥0.5 | <0.5≥0 | Samples (cases)** |

≥10 | <10≥5 | <5≥1 | <1≥0.5 | <0.5≥0 | Samples (cases)** |

| Anti-CCP | 0.00 (0) | 0.08 (3) | 0.53 (19) | 0.22 (8) | 0.17 (6) | 36 (26) | 0.06 (2) | 0.29 (10) | 0.46 (16) | 0.08 (3) | 0.14 (5) | 35 (25) |

| RF-IgA | 0.00 (0) | 0.12 (3) | 0.38 (10) | 0.23 (6) | 0.27 (7) | 26 (20) | 0.07 (2) | 0.23 ( 7) | 0.41 (11) | 0.11 (3) | 0.18 (5) | 27 (20) |

| Rf-IgG | 0.00 (0) | 0.18 (2) | 0.46 ( 5) | 0.00 (0) | 0.36 (4) | 11 (9) | 0.00 (0) | 0.26 ( 5) | 0.47 ( 9) | 0.15 (3) | 0.15 (3) | 19 (15) |

| RF-IgM | 0.00 (0) | 0.13 (3) | 0.44 (10) | 0.17 (4) | 0.26 (6) | 23 (18) | 0.08 (3) | 0.34 (12) | 0.37 (13) | 0.08 (3) | 0.14 (5) | 35 (23) |

| High Risk*** | 0.00 (0) | 0.10 (4) | 0.51 (20) | 0.20 (8) | 0.18 (7) | 39 (27) | 0.08 (3) | 0.27 (10) | 0.46 (17) | 0.08 (3) | 0.14 (5) | 37 (27) |

| Eotaxin | 0.00 (0) | 0.17 (1) | 0.33 (2) | 0.17 (1) | 0.33 (2) | 6 (5) | 0.00 (0) | 0.80 (4) | 0.20 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) | 5 (5) |

| FGF2 | 0.00 (0) | 0.19 (4) | 0.52 (11) | 0.10 (2) | 0.19 (4) | 21 (17) | 0.00 (0) | 0.31 (4) | 0.38 (5) | 0.14 (2) | 0.21 (3) | 13 (11) |

| FLT3 | 0.07 (2) | 0.15 (4) | 0.52 (14) | 0.11 (3) | 0.15 (4) | 27 (22) | 0.00 (0) | 0.46 (11) | 0.42 (10) | 0.04 (1) | 0.08 (2) | 24 (20) |

| GMCSF | 0.11 (3) | 0.18 (5) | 0.41 (11) | 0.11 (3) | 0.19 (5) | 27 (20) | 0.6 (1) | 0.35 (6) | 0.53 (9) | 0.00 (0) | 0.06 (1) | 17 (13) |

| IL1α | 0.08 (2) | 0.08 (2) | 0.54 (14) | 0.12 (3) | 0.19 (5) | 26 (17) | 0.03 (1) | 0.38 (11) | 0.41 (12) | 0.07 (2) | 0.10 (3) | 29 (22) |

| IL1β | 0.00 (0) | 0.11 (2) | 0.50 (9) | 0.17 (3) | 0.22 (4) | 18 (15) | 0.00 (0) | 0.41 (7) | 0.29 (5) | 0.06 (1) | 0.23 (4) | 17 (13) |

| IL6 | 0.00 (0) | 0.07 (1) | 0.47 (7) | 0.20 (3) | 0.27 (4) | 15 (13) | 0.07 (1) | 0.40 (6) | 0.40 (6) | 0.07 (1) | 0.07 (1) | 15 (12) |

| IL10 | 0.10 (2) | 0.15 (3) | 0.50 (10) | 0.05 (1) | 0.20 (4) | 20 (18) | 0.10 (1) | 0.40 (4) | 0.50 (5) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) | 10 (9) |

| IL12P40 | 0.07 (2) | 0.11 (3) | 0.59 (16) | 0.07 (2) | 0.15 (4) | 27 (21) | 0.04 (1) | 0.36 (10) | 0.46 (13) | 0.07 (2) | 0.10 (3) | 28 (20) |

| IL12P70 | 0.10 (2) | 0.10 (2) | 0.47 (9) | 0.11 (2) | 0.21 (4) | 19 (16) | 0.00 (0) | 0.38 (5) | 0.54 (7) | 0.00 (0) | 0.08 (1) | 13 (13) |

| IL15 | 0.04 (1) | 0.18 (4) | 0.50 (11) | 0.04 (1) | 0.23 (5) | 22 (18) | 0.00 (0) | 0.27 (4) | 0.47 (7) | 0.19 (3) | 0.12 (2) | 15 (13) |

| IP10 | 0.00 (0) | 0.12 (3) | 0.63 (15) | 0.04 (1) | 0.21 (5) | 27 (19) | 0.11 (3) | 0.38 (10) | 0.38 (10) | 0.04 (1) | 0.08 (2) | 26 (22) |

| MCP | 0.00 (0) | 0.24 (4) | 0.47 (8) | 0.06 (1) | 0.23 (4) | 17 (13) | 0.17 (3) | 0.39 (7) | 0.33 (6) | 0.00 (0) | 0.11 (2) | 18 (14) |

| TNFα | 0.00 (0) | 0.19 (4) | 0.48 (10) | 0.09 (2) | 0.24 (5) | 21 (17) | 0.10 (2) | 0.47 (9) | 0.31 (6) | 0.05 (1) | 0.10 (2) | 19 (16) |

| CRP>5 | 0.00 (0) | 0.07 (1) | 0.36 (5) | 0.285 (4) | 0.285 (4) | 14 (13) | 0.09 (2) | 0.32 (7) | 0.41 (9) | 0.04 (1) | 0.14 (3) | 22 (16) |

| CRP>10 | 0.00 (0) | 0.12 (1) | 0.12 (1) | 0.375 (3) | 0.375 (3) | 8 (8) | 0.00 (0) | 0.50 (4) | 0.38 (3) | 0.00 (0) | 0.12 (1) | 8 (8) |

| 0-4 positive**** | 0.09 (4) | 0.28(13) | 0.39 (18) | 0.13 (6) | 0.11 (5) | 46 (26) | 0.22(11) | 0.32 (16) | 0.36 (18) | 0.02 (1) | 0.08 (4) | 50 (33) |

| 5-9 positive**** | 0.08 (1) | 0.23 (3) | 0.54 (7) | 0.15 (2) | 0.00 (0) | 13 (12) | 0.00 (0) | 0.22 (2) | 0.44 (4) | 0.20 (2) | 0.20 (2) | 9 (9) |

| 10+ positive**** | 0.00 (0) | 0.08 (1) | 0.50 (6) | 0.09 (1) | 0.33 (4) | 12 (11) | 0.00 (0) | 0.56 (5) | 0.33 (3) | 0.00 (0) | 0.11 (1) | 9 (9) |

| Cases (samples) for each interval |

5 (5) | 17 (27) | 31 (56) | 9 (9) | 9 (9) | 11 (14) | 23 (40) | 25 (42) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | ||

- Time period ≥10 years prior-to-diagnosis, <40 median count 0.5; ≥40 median count 1.0; p=0.43

- Time period <10 to ≥5 years prior-to-diagnosis, <40 median count 3.0; ≥40 median count 6.5, p<0.01

- Time period <5 to ≥1 years prior-to-diagnosis, <40 median count 10.5; ≥40 median count 6.5, p=0.01

- Time period <1 to ≥0 years prior-to-diagnosis (combined samples ≤1 year prior-to-diagnosis), <40 median count 6.0; ≥40 median count 3.0, p<0.01

In rows, the initial number X in each column represents the proportion of samples during that interval that was positive for the given biomarkers; the following number (in parentheses) represents the raw number of samples that were positive during this interval. The proportion of samples positive is calculated by dividing the number of samples positive by the total number of samples positive for each biomarker, which is listed in the final column for each age-at-diagnosis group.

In these columns, these numbers X(X) represent, respectively, the total number of samples that were positive for each biomarker during the entire pre-clinical RA period, and the number of cases that were positive for this biomarker at any point in the pre-diagnosis period.

High risk = Anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes, positivity for which in any pre-clinical sample is 74% sensitive and >96% specific for future RA

These values are ranges of numbers of cytokines/chemokines that were positive

Abbreviations: Anti-CCP=anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; RF=rheumatoid factor; Ig=immunoglobulin; high-risk = anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes positive (>96% specific for future sero-positive RA); interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, Eotaxin ( or CCL11), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), Flt-3 ligand, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon gamma induced protein-10 (IP-10)( or CXCL10), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (or CCL-2); CRP=C-reactive protein

Cytokine/chemokine stability

To evaluate the possible degradation of cytokines/chemokines over time due to storage, cytokine/chemokine counts in samples from a 2-year pre-diagnosis period in 8 cases diagnosed with seropositve RA in 1991 were compared to counts in pre-diagnosis samples from a 2-year period from 8 cases diagnosed in 2002. In this comparison, there was no significant differences in the mean cytokine/chemokine count (counts 5.3 versus 5.6; p=0.84), suggesting that cytokine/chemokine degradation over the ~11 year increase in storage time did not affect results.

We also investigated the fluctuations of biomarker positivity in pre-diagnosis seropositive RA. For autoantibodies, reversion from positive to negative occurred in <7% of cases, regardless of autoantibody type. For cytokines/chemokines, overall there were 271 conversions from negative to positive for at least one cytokine/chemokine, and 184 reversions from positive to negative (all conversions/reversions out of 212 pre-diagnosis samples from 73 cases). However, 75% of case cytokine/chemokine conversions to positive occurred ≤5 years prior-to-diagnosis, and more cases had persistent cytokine/chemokine positivity once positive leading to the overall increase in cytokine/chemokines counts demonstrated in Figure 1. Additional biomarker stability data is presented in the on-line Supplemental Table A.

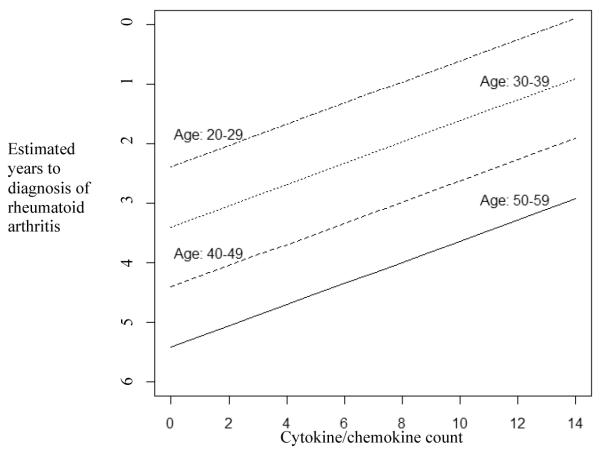

Prediction of time-to-diagnosis of future RA (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Estimation of time-to-diagnosis of future rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by age and cytokine/chemokine counts in subjects with autoantibody positivity highly specific for future RA.

This figure represents the results from regression modeling of the outcome time-to-diagnosis of future RA, based on predictor variables of age-at-diagnosis (by decade) and cytokine/chemokine count (p-value for model <0.01). Pre-diagnosis RA case samples included to develop this model were those that were positive for the highly RA-specific (>96%) autoantibodies: anti-CCP and/or 2 or more rheumatoid factor isotypes (N=54 cases with 101 pre-RA diagnosis samples). For example, from this model, in a case diagnosed with RA between ages 50-59, a sample with a cytokine/chemokine count of 10 would be ~4 years prior-to-diagnosis, while for the same cytokine/chemokine count, a sample from an individual in the 20-29 age-group would be ~1 year prior-to-diagnosis. Model: Years to Diagnosis = −2.3861 - 1.0122 × (Decade*) + 0.1782 × (Cytokine/Chemokine count) *Decade 20-29 coded as 0, 30-39 coded as 1, etc.

To develop a regression model clinically useful in prospective studies for prediction of the time of onset of future seropositive RA in subjects highly likely to develop future RA, we used only pre-diagnosis case samples that were positive for anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes, as this autoantibody profile was reasonably sensitive (74%) and highly specific (>96%) for future seropositive RA (Table 2). Fifty-four seropositive RA cases (61% male, mean age-at-diagnosis 39.1) had 101 pre-diagnosis samples that were positive for this autoantibody profile (samples collected a mean of 3.6 years prior-to-diagnosis). The outcome for this analysis was the duration of time between pre-clinical sample and the diagnosis of RA, and initial predictor variables evaluated were gender, race, autoantibody levels, CRP, individual and counts of positive cyotokine/chemokines, and age-at-diagnosis (by decade). Of note, the variable age-at-diagnosis by decade intervals (rather than <40, ≥40) was created to allow for finer analysis of the relationship of age to the duration of pre-diagnosis biomarker positivity. Also, in a separate analysis, the means of the durations from initial pre-clinical sample to diagnosis of RA between groups showed no significant differences (p=0.46).

Predictor variables for the time-to-diagnosis retained after backward elimination of covariates were 1) ‘cytokine/chemokine count’, (β=0.1782, p=0.01) and 2) age-at-diagnosis (by decade) (β=−1.0122, p=0.02). In this model, the period of time from the pre-clinical sample to diagnosis of RA decreased as the number of cytokines/chemokines that were positive in the sample increased (model significance, p<0.01) (Figure 2). Also, as age-at-diagnosis increased (by decade), there was also a corresponding increase in the duration of time from sample collection to the diagnosis of RA. Gender, race and positivity for individual cytokines/chemokines or CRP did not contribute significantly to this model. Finally, while there was a trend of increased levels of autoantibodies (continuous) and CRP (dichotomous or continuous) closer to diagnosis, these levels did not contribute significantly to this model (data not shown).

Biomarker positivity in relationship to symptom onset

Limited data regarding the duration of pre-diagnosis joint symptoms was available from chart review from 56/73 (~77%) seropositive RA cases. The median onset of symptoms prior-to-diagnosis in these 56 cases was 0.5 years, with no difference in median time of onset of symptoms between age-at-diagnosis groups (symptom onset median 0.5 years prior-to-diagnosis for groups <40, ≥40;p=0.75). To evaluate cytokine/chemokine positivity prior to symptom onset in these 56 cases, samples from 0-6 months prior-to-diagnosis were removed from analysis. After removal of these samples (28 case/control samples, including removal of 4 cases/controls as their only pre-diagnosis samples were from this period), the differences in proportions of cases versus controls positive for the following biomarkers were lost: Flt 3 ligand, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, and CRP >5 mg/L (but not >10 mg/L). These findings indicate that there is a substantial number of cases with elevations of these cytokines/chemokines during the 0-6 month period prior to formal RA diagnosis, although notably these same cytokines/chemokines were positive in a subset of cases prior to 6 months pre-diagnosis (Table 4). Also, we repeated the predictive model for time of onset of future RA in case samples positive for anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes, but with movement of the ‘outcome’ from time of diagnosis to 6 months prior, leading to a smaller sample set of N=48 cases with 89 samples (6 cases and 12 samples were present in this 0-6 pre-diagnosis window). Compared to the original analysis, this analysis showed similar results in that increasing age-at-diagnosis was associated with longer time to diagnosis for a given cytokine/chemokine count (p=0.01). Also, consistent with the removal of samples with increasing cytokine/chemokine counts from the 0-6 months prior-to-diagnosis (seen in Figure 1), the Y-intercepts were moved earlier in the pre-diagnosis period, the rate of progression to the endpoint was less (decreased slope), and cytokine/chemokine count as a predictors of the outcome was marginally significant (p=0.06) Results from this additional analysis are provided in the on-line Supplemental Figure B.

Discussion

Supporting findings in prior studies, in this cohort of military patients with RA we have identified that autoantibodies, circulating cytokines/chemokines and CRP are elevated pre-clinical RA, and that autoantibody positivity is highly specific for future seropositive RA.(10-12, 14, 16, 17) We have additionally shown that there is an increased duration of pre-clinical biomarker positivity in individuals with older age-at-diagnosis, and we have developed a regression model that utilizes cytokine/chemokine counts and age-at-diagnosis to estimate the time from pre-clinical sample to the time of RA diagnosis. Importantly, since this model was developed using pre-diagnosis case samples positive for highly RA-specific autoantibodies (anti-CCP and/or 2 or more RF isotypes), in prospective study of individuals without symptomatic RA but who are positive for these autoantibodies, application of this model will allow for prediction of age-related timing of onset of symptomatic disease as well as identification of subjects who may be ideal candidates for prevention trials due to their likely imminent onset of symptomatic disease. Of note, while this RA-specific autoantibody profile is most likely to be positive within 5-years prior-to-diagnosis, it may be present up to 10 years pre-diagnosis (Table 3). As such, cytokine/chemokine analyses in these high-risk subjects allows for finer specification of time-to-diagnosis than autoantibody testing alone. Also, while this model used age-at-diagnosis (by decade) to predict the time-to-diagnosis in RA cases, it will apply to estimate the timing of onset of future symptomatic RA in asymptomatic subjects followed prospectively with current age replacing age-at-diagnosis, as the 10-year intervals allow for adequate bracketing of subjects into age groups where the biologic and other factors influencing duration of pre-clinical biomarker positivity are appropriately accounted for.

The relationship between age and the increased duration of pre-RA diagnosis biomarker positivity identified here and in prior studies (13, 18) may be due to differing genetic and environmental influences on disease development in younger versus older cases, or may be due to factors related to senescence of the effecter mechanisms of the immune system in older subjects.(13, 28) Non-biologic factors may also influence the duration of pre-diagnosis autoimmunity and inflammation in military RA subjects. For example, older military subjects may be less likely to present to health-care with medical complaints to protect their work or retirement status, or they may be more likely to be in engaged in sedentary tasks where joint symptoms may be less debilitating, although herein there was no difference in time of onset of pre-diagnosis symptoms by age-at-diagnosis grouping. Furthermore, younger military subjects may appear comparatively to have a shorter pre-clinical duration of biomarker positivity because they have a smaller temporal span of pre-clinical samples available than older subjects. However, as the mean duration from first pre-clinical sample to diagnosis was not significantly different between age groups (by decade) used in the prediction model, this was likely not a significant issue here. Also, there may be an unidentifiable duration of pre-clinical biomarker positivity if subjects’ earliest available pre-diagnosis samples were biomarker positive – we investigated this issue and found that there was no significant difference between age-at-diagnosis groups (<40, ≥40) in the number of initial pre-clinical samples that were positive for a biomarker, with the exception that GM-CSF was positive in the initial sample in a higher proportion of cases <40 at diagnosis. And, for all autoantibodies and IL-1α, IL-6, IL-15, IP-10, MCP-1 and CRP, there was a non-statistically significant trend for the ≥40 group to have an increased proportion of first-sample biomarker positivity, suggesting that the longer duration of biomarker positivity pre-RA diagnosis in older cases may actually be underestimated. In sum, age-related duration of pre-RA diagnosis biomarker positivity in this population is likely a real phenomenon, important for understanding the evolution of RA as well as developing models to predict the timing of onset of future disease.

The elevations of the cytokines/chemokines assessed here likely reflect various underlying processes including: general inflammation (IL-1α and β, TNFα, IL-6, CRP), Th1-related processes (IL-12), Th2-related processes (eotaxin), T cell regulation (IL-10, IL-15), or cellular signaling/growth factors (FGF-2, Flt3 Ligand, GM-CSF). Due to limitations in the size of our sample set and number/type of cytokines/chemokines assessed here, inferences regarding the biology and timing of specific immune responses in pre-clinical RA are likewise limited; however, there are several findings of particular interest. Firstly, IL-6 elevation in a subset of subjects prior to anti-CCP positivity is of interest as this cytokine is associated with Th17 cell development – cells thought to be important in RA pathogenesis (29). IL-17 and IL-23 are also important factors in this pathway, and although we did not assess these cytokines, Kokkonen et al demonstrated pre-RA elevations of IL-17 (16), and their findings coupled with ours suggest that the Th17 pathway is important in pre-clinical RA. Secondly, IP-10 elevation prior to anti-CCP positivity is of interest in terms of disease pathogenesis, as this chemokine is an IFNγ-induced protein promoting chemoattraction for macrophages, dendritic cells and T cells, as well as in terms of therapeutics, as blockade of IP-10 has reduced the severity of collagen-induced arthritis in mice.(30) Thirdly, the increased proportion of IL-10 positivity in cases that were <40 at diagnosis is of also of interest, with the T cell regulatory aspects of this cytokine perhaps playing a role in age-of-onset of disease.(31) Fourthly, the pre-clinical fluctuations in positivity of individual cytokines/chemokines likely reflects that inflammation, due to evolving immune reactions and/or level of tissue injury, builds and eventually reaches a threshold state when an individual transitions from asymptomatic autoimmunity/inflammation to clinically-apparent disease (although the exact anatomic site(s) of these early inflammatory/autoimmune processes in pre-clinical RA are unknown). Furthermore, the loss of significant differences in pre-clinical positivity for a subset of biomarkers when samples from 0-6 months prior-to-diagnosis were removed from analyses highlights that the immediate pre-diagnosis period is a time of increasing systemic inflammation, when early RA symptoms may be present, although statistical power issues due to loss of samples, and possible inaccuracies in patient recall of symptom onset may be factors here.(32) Of note, because of overlap between increasing cytokines/chemokines and symptoms during this immediate pre-diagnosis period, these military cases may be similar to the Dutch patients described by Bos, Verweij and colleagues who have autoantibody positivity and arthralgia as well as increased gene expression for cytokines/chemokines but no clinical synovitis who may later progress to definable RA.(33, 34) Finally, while CRP levels did not predict the time of onset of RA, the highest proportion of cases with CRP positivity was <1 year pre-diagnosis, suggesting that CRP elevation in an at-risk individual may indicate impending onset of symptomatic RA. All of these latter issues will need to be explored prospectively in additional sample sets, where shortcomings of ascertainment of pre-diagnosis symptoms in retrospectively assembled cohorts can be addressed.

There are other caveats to our findings. There are not standardized cut-offs for positivity for cytokines/chemokines using the methodology presented here (Luminex), and our cut-offs for positivity may not be applicable to other populations. Also, because our cut-off levels were established using post-RA diagnosis samples, treatment factors may influence these levels, although it is likely that these levels were higher than may be expected in the pre-clinical period, leading to conservative estimates of pre-diagnosis cytokine/chemokine positivity. Notably, there were differences in the diagnostic accuracy of cytokines/chemokines for future RA in our study compared to that by Kokkonen et al -- on average we found ~42% sensitivity and ~74% specificity of the individual 14 cytokines/chemokines for future RA compared to an average of ~17% sensitivity and a set ~95% specificity of any of the 15 cytokines reported in the study by Kokkonen and colleagues.(16) These differences may be due to RA case ascertainment, methodologies of biomarker testing, and methodologies to determine cut-off values and sensitivity/specificity for the biomarkers for future RA. Additionally, compared to testing a single pre-diagnosis sample, our testing of multiple pre-diagnosis samples per individual likely allows for greater sensitivity to detect elevations, especially given the fluctuations of cytokines/chemokines positivity demonstrated here. In the future, standardization of cytokine/chemokine assessment and cut-offs for positive will overcome many of these issues. There may also be non-RA related factors affecting cytokine/chemokine, levels including methodologies of sample collection and sample storage.(35) And, while military subjects were to have blood sampled for the DoDSR at defined times, it is possible that they preferentially had sampling during times of illness. However, by using samples from carefully-matched military controls for comparisons, we believe that such effects are accounted for. Regarding the wider applicability of these findings, this military cohort may not represent typical RA in the general population – it was predominately male, and the mean age of onset of disease was earlier than seen in the general population. There also may be biases in terms of which military subjects are referred for rheumatology evaluation, and these cases may represent more severe RA, evidenced by a relatively high proportion of seropositive disease (~88%). These concerns, as well as the role of genetic and environmental factors (such as smoking) in prediction of RA, need to be addressed by application of this model in additional populations.

Conclusion

Elevations of autoantibodies and multiple cytokines/chemokines can be used, in autoantibody positive subjects at high-risk for future RA, to predict the timing of diagnosis. Going forward, validation of this model should be performed using existing bio-repositories as well as ongoing prospective studies of individuals at-risk for future RA (36, 37), with goals to understand the biology of RA development and to identify subjects that can be considered for preventive interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kristen Braschler for her assistance in the autoantibody assays, and Gary O. Zerbe, PhD for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Grant support: NIH AR51394, AI50864, AR051461 (Deane, O’Donnell, Derber, Norris and Holers), T32 CA-09337 (Lazar) and AR058713, AR054822 and American College of Rheumatology (Robinson)

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Disclosure: A patent application that includes Drs. Deane, Hueber, Robinson and Holers has been filed for the use of biomarkers to predict clinically actionable events in rheumatoid arthritis. In addition, licensing agreements regarding the use of biomarkers have been established.

References

- 1.del Puente A, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Bennett PH. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis is predicted by rheumatoid factor titer in a longitudinal population study. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Oct;31(10):1239–44. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aho K, Heliovaara M, Maatela J, Tuomi T, Palosuo T. Rheumatoid factors antedating clinical rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991 Sep;18(9):1282–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurki P, Aho K, Palosuo T, Heliovaara M. Immunopathology of rheumatoid arthritis. Antikeratin antibodies precede the clinical disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1992 Aug;35(8):914–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aho K, von Essen R, Kurki P, Palosuo T, Heliovaara M. Antikeratin antibody and antiperinuclear factor as markers for subclinical rheumatoid disease process. J Rheumatol. 1993 Aug;20(8):1278–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aho K, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Reunanen A, Aromaa A, Leino A, et al. Serum immunoglobulins and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997 Jun;56(6):351–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.6.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aho K, Palosuo T, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Alha P, von Essen R. Antifilaggrin antibodies within “normal” range predict rheumatoid arthritis in a linear fashion. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec;27(12):2743–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Oct;48(10):2741–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berglin E, Padyukov L, Sundin U, Hallmans G, Stenlund H, Van Venrooij WJ, et al. A combination of autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and HLA-DRB1 locus antigens is strongly associated with future onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(4):R303–8. doi: 10.1186/ar1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MH, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb;50(2):380–6. doi: 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, Twisk JW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. Increased levels of C-reactive protein in serum from blood donors before the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Aug;50(8):2423–7. doi: 10.1002/art.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, Twisk JW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. Simultaneous development of acute phase response and autoantibodies in preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Apr;65(4):535–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Boman K, Tarkowski A, Hallmans G. Up regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in anti-citrulline antibody and immunoglobulin M rheumatoid factor positive subjects precedes onset of inflammatory response and development of overt rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jan;66(1):121–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.057331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majka DS, Deane KD, Parrish LA, Lazar AA, Baron AE, Walker CW, et al. Duration of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis-related autoantibody positivity increases in subjects with older age at time of disease diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jun;67(6):801–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen KT, Wiik A, Pedersen M, Hedegaard CJ, Vestergaard BF, Gislefoss RE, et al. Cytokines, autoantibodies and viral antibodies in premorbid and postdiagnostic sera from patients with rheumatoid arthritis: case-control study nested in a cohort of Norwegian blood donors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jun;67(6):860–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadick NA, Cook NR, Karlson EW, Ridker PM, Maher NE, Manson JE, et al. C-reactive protein in the prediction of rheumatoid arthritis in women. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Dec 11-25;166(22):2490–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokkonen H, Soderstrom I, Rocklov J, Hallmans G, Lejon K, Dahlqvist S Rantapaa. Up-regulation of cytokines and chemokines predates the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Jan 7;62(2):383–91. doi: 10.1002/art.27186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlson EW, Chibnik LB, Tworoger SS, Lee IM, Buring JE, Shadick NA, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and development of rheumatoid arthritis in women from two prospective cohort studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Mar;60(3):641–52. doi: 10.1002/art.24350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos WH, Nielen MM, Dijkmans BA, van Schaardenburg D. Duration of pre-rheumatoid arthritis anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide positivity is positively associated with age at seroconversion. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Nov;67(11):1642. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonsson T, Steinsson K, Jonsson H, Geirsson AJ, Thorsteinsson J, Valdimarsson H. Combined elevation of IgM and IgA rheumatoid factor has high diagnostic specificity for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1998;18(3):119–22. doi: 10.1007/s002960050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Kawano S, et al. Meta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jun 5;146(11):797–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alarcon GS, Koopman WJ, Acton RT, Barger BO. Seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. A distinct immunogenetic disease? Arthritis Rheum. 1982 May;25(5):502–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Mar;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueber W, Tomooka BH, Zhao X, Kidd BA, Drijfhout JW, Fries JF, et al. Proteomic analysis of secreted proteins in early rheumatoid arthritis: anti-citrulline autoreactivity is associated with up regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jun;66(6):712–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.054924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szodoray P, Alex P, Chappell-Woodward CM, Madland TM, Knowlton N, Dozmorov I, et al. Circulating cytokines in Norwegian patients with psoriatic arthritis determined by a multiplex cytokine array system. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007 Mar;46(3):417–25. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004 Dec;8(6):508–12. doi: 10.1186/cc3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982 Dec;38(4):963–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young DA, Zerbe GO, Hay WW., Jr. Fieller’s theorem, Scheffe simultaneous confidence intervals, and ratios of parameters of linear and nonlinear mixed-effects models. Biometrics. 1997 Sep;53(3):838–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Stem cell aging and autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Trends Mol Med. 2004 Sep;10(9):426–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brennan F, Beech J. Update on cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007 May;19(3):296–301. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32805e87f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwak HB, Ha H, Kim HN, Lee JH, Kim HS, Lee S, et al. Reciprocal cross-talk between RANKL and interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 is responsible for bone-erosive experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 May;58(5):1332–42. doi: 10.1002/art.23372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Loo FA, van den Berg WB. Immunocytokines: the long awaited therapeutic magic bullet in rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):132. doi: 10.1186/ar2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amjadi-Begvand S, Khanna D, Park GS, Bulpitt KJ, Wong WK, Paulus HE. Dating the “window of therapeutic opportunity” in early rheumatoid arthritis: accuracy of patient recall of arthritis symptom onset. J Rheumatol. 2004 Sep;31(9):1686–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bos WH, Wolbink GJ, Boers M, Tijhuis GJ, de Vries N, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. Arthritis development in patients with arthralgia is strongly associated with anti-citrullinated protein antibody status: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Mar;69(3):490–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Baarsen LG, Bos WH, Rustenburg F, van der Pouw Kraan TC, Wolbink GJ, Dijkmans BA, et al. Gene expression profiling in autoantibody-positive patients with arthralgia predicts development of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Mar;62(3):694–704. doi: 10.1002/art.27294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aziz N, Nishanian P, Mitsuyasu R, Detels R, Fahey JL. Variables that affect assays for plasma cytokines and soluble activation markers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999 Jan;6(1):89–95. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.89-95.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, O’Donnell C, Weisman MH, Buckner JH, et al. A prospective approach to investigating the natural history of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using first-degree relatives of probands with RA. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Dec 15;61(12):1735–42. doi: 10.1002/art.24833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Gabalawy HS, Robinson DB, Hart D, Elias B, Markland J, Peschken CA, et al. Immunogenetic risks of anti-cyclical citrullinated peptide antibodies in a North American Native population with rheumatoid arthritis and their first-degree relatives. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jun;36(6):1130–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.