Abstract

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) episodes may occur upon exposure to halogenated anesthetics, during resistance and endurance exercise, and in response to thermal stress. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of prior eccentric and concentric (i.e., wheel running) exercise on the thermal sensitivity of isolated MH susceptible mouse muscle (RyR1Y522S/wt). Eccentric, but not concentric, exercise attenuated the thermal sensitivity of MH susceptible muscle.

Keywords: Malignant hyperthermia, eccentric contractions, muscle injury, thermal sensitivity, RyRY522S/wt, mouse, Junctophilin 1

Introduction

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) has traditionally been described as a pharmacogenetic disorder, whereupon genetic mutations, mostly of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor; RyR1), confer hypersensitivity to halogenated anesthetics.1 MH susceptible (MHS) individuals have been reported to experience episodic symptoms such as acidosis, rhabdomyolysis and even death after exposure to halogenated anesthetics. Symptoms also are reported to occur after endurance and resistance exercise and in response to thermal stress,2,3,4,5 raising the possibility that MH, environmental heat illness, and exertional rhabdomyolysis are related conditions.6 In support of this conclusion, MH episodes may be induced in MHS mice (RyR1Y522S/wt) solely by thermal stress,7,8 and these episodes have been attributed to an enhanced post-translational modification of the RyR1.8 We have reported that RyR1Y522S/wt mice can perform voluntary wheel running and eccentrically-biased exercise under non-stressful thermal conditions without inducing episodic symptoms.9,10 Because some individuals with MH likely participate in resistance and/or endurance training, it is important to understand the effect of prior eccentric or concentric exercise on the thermal sensitivity of MHS muscle.

Methods

Animals

The generation of MHS mice with heterozygous expression of Y522S mutation in RyR1 (RyR1Y522S/wt) has been described previously.7 Wild type (WT; C57BL6) mice served as genetic controls. All animal care and use procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Experimental Design & Methodology

Mice were allotted to the following experimental groups: Single bout of 150 eccentric contractions, four bouts of 150 eccentric contractions (one per week for four weeks), or four weeks of voluntary wheel running. Eccentric contractions were performed with the left anterior crural muscles [e.g., tibialis anterior (TA) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles] using an in vivo injury model.10,11,12,13 Core body temperature during the eccentric contractions was ~35°C, and wheel running was performed at an ambient temperature of ~22°C. A description of the effects of eccentric contractions and wheel running on RyR1Y522S/wt in vivo anterior crural muscle functional capacity is provided elsewhere.9,10

Immediately, three days, and 14 days after a single eccentric bout (i.e., Ecc-0d, Ecc-3d, & Ecc-14d), three days after repeated eccentric bouts (Ecc-T), and two days after cessation of voluntary wheel running (Run), the left EDL muscles were dissected from anesthetized mice (100 mg·kg-1 pentobarbital sodium) and studied in vitro.10,11,12,13 Muscles were incubated at 30°C and then at 35°C for 30 minutes at each temperature, while resting tension was monitored at three-minute intervals. Peak isometric force (300 Hz; 200-ms trains of 0.2-ms pulses) was measured at the end of each incubation period. Caffeine (50mM) contracture force was assessed after the 35°C incubation. Junctophilin 1 (Invitrogen 40-5100) protein content, a protein involved in the apposition of transverse tubule and SR membranes, was normalized to tubulin content as determined via Western blot.13

Statistics

Comparative analyses were performed using a variety of ANOVAs. Post-hoc means comparisons tests were performed with Bonferonni correction. α was set at 0.05. Values are reported as means ± SEM.

Results

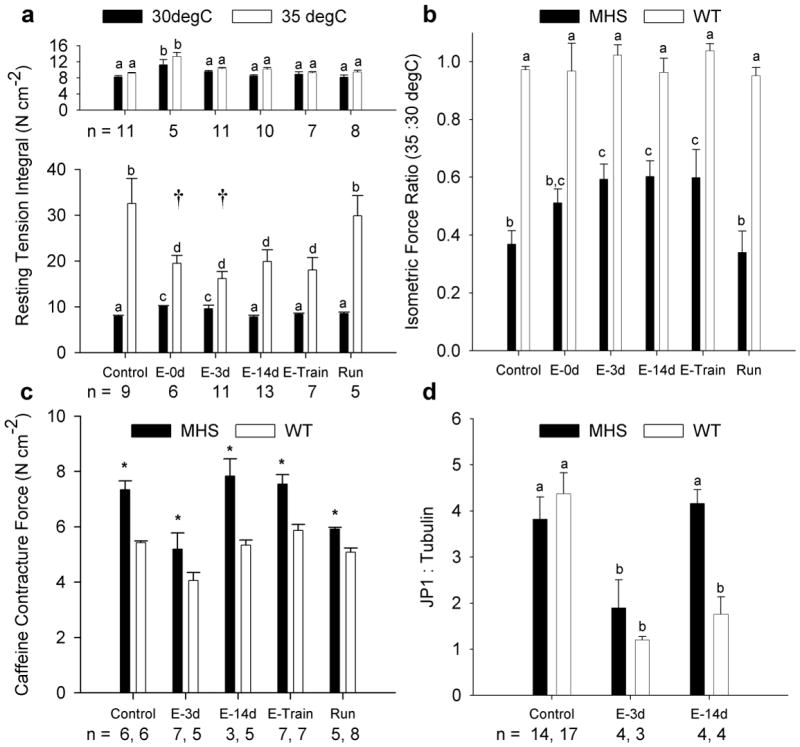

When incubation temperature was increased from 30° to 35°C, neither resting tension integral nor active force values (e.g., Control WT 30 vs. 35°C; 23.1±0.6 vs. 22.0±0.7 N·cm-2) were significantly altered for WT mice under any condition. In contrast, control RyR1Y522S/wt muscle exhibited an ~3.1-fold increase in resting tension integral and an ~65% decrease in active force (30 vs. 35°C; 21.4±0.9 vs. 7.7±1.0 N·cm-2) when incubation temperature was increased from 30° to 35°C. The temperature-associated increase in resting tension integral and decrease in active force production were attenuated in MHS EDL muscle after a single or multiple bouts of eccentric contractions, but not after 4 weeks of voluntary wheel running (Fig. 1a, b). MHS EDL muscle caffeine contracture force was qualitatively similar to values we have reported previously for uninjured and injured RyR1Y522S/wt EDL muscle, and it was greater than WT values under each condition (Fig 1c).10 Serving as an indirect marker of triad disruption and then repair,13 JP1 was reduced three days after a single eccentric bout in WT and MHS muscle but was only recovered to baseline values in MHS muscle (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Effects of prior exercise on temperature sensitivity and functional capacity of MH susceptible muscle. (a) The total tension produced over the 30-minute incubation periods (i.e., resting tension integral) were compared between WT (top panel) and RYR1Y522S/wt (bottom panel) mice and among conditions. See methods section for definition of groups. There were no significant differences between WT and RYR1Y522S/wt values for any condition at 30°C, while only E-0d and E-3d values were similar (†) between genotypes at 35°C. (b) Peak isometric specific force of WT and RYR1Y522S/wt muscle produced at 35°C, expressed as a ratio of force produced at 30°C, was compared between genotypes and among conditions. (c) Caffeine contracture force for WT and RYR1Y522S/wt muscle produced at 35°C. * denotes a significant main effect of genotype (p < 0.001). (d) JP1:Tubulin values for WT and RYR1Y522S/wt tibialis anterior muscles. Within each panel, values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). All values are expressed as means ± SEM; sample sizes (n) are similar for (a & b).

Discussion

These preliminary results indicate that high-force eccentric contractions (resistance-like exercise) performed under non-thermally stressful conditions, but not voluntary wheel running, attenuate the thermal stress-induced loss of function in MHS muscle with the Y522S RyR1 mutation for a prolonged period of time. Therefore, exercise-induced muscle injury may blunt the severity of a thermally related MH episode in humans. Furthermore, this finding may have implications on the interpretation of diagnostic contracture tests used to assess MH susceptibility in individuals who routinely engage in strength training exercise.

How eccentric contractions attenuate the thermal stress-induced loss of function of MHS muscle is unknown. However, because enhanced MHS muscle thermal sensitivity in RyR1Y522S/wt mice has been ascribed to an altered RyR1 stability due to enhanced nitrosylation and oxidation, 8 it is likely that an attenuated thermal response in MHS muscle after eccentric contractions is due to an improved RyR1 stability. One possible explanation for the attenuated thermal response after eccentric contractions is that triad re-structuring, as is indicated by the loss and recovery of JP1 after eccentric contractions,13 improves RyR1 stability in MHS muscle. With triad re-structuring following injury, it is likely that a number of accessory triadic proteins that are known to modulate RyR1 channel activity (e.g., JP-45 & MG-29) are damaged and replaced and that this re-structuring may provide improved stability to RyR1 in MHS muscle. For example, it has been shown that JP1 binds to RyR1 in a redox sensitive manner that may increase RyR1 open probability, 14 indicating that the loss of JP1 after eccentric contractions may partly explain early time-point reductions in thermal sensitivity. Further study is currently being conducted to improve our understanding of the effects of eccentric contractions on triad structure and how these effects are related to early and prolonged eccentric contraction induced-attenuation of thermal sensitivity in MHS muscle.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Arthritis andMusculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant AR-41802 (to S. L. Hamilton). We would like to thank Mr. Clement Rouviere for overseeing the mouse wheel running training.

Abbreviations

- Cav1.1

Voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel

- EDL muscle

Extensor digitorum longus

- JP1

Junctophilin 1

- JP-45

Junctional Protein 45

- MHS

Malignant hyperthmia (MH) susceptible

- MG-29

Mitsugumin 29

- RyR1

Ryanodine receptor 1

- SR

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TA muscle

Tibialis anterior

- WT

Wild type

References

- 1.Rosenberg H, Davis M, James D, Pollock N, Stowell K. Malignant hyperthermia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:21–35. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochling A, Wappler F, Winkler G, Schulte am Esch JS. Rhabdomyolysis following severe physical exercise in a patient with predisposition to malignant hyperthermia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26:315–318. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9802600317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishio H, Sato T, Fukunishi S, Tamura A, Iwata M, Tsuboi K, Suzuki K. Identification of malignant hyperthermia-susceptible ryanodine receptor type 1 gene (RYR1) mutations in a child who died in a car after exposure to a high environmental temperature. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan JF, Tedeschi LG. Sudden unexplained death in a patient with a family history of malignant hyperthermia. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:66–68. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(96)00207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wappler F, Fiege M, Steinfath M, Agarwal K, Scholz J, Singh S, Matschke J, Schulte Am Esch J. Evidence for susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia in patients with exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:95–100. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capacchione JF, Muldoon SM. The relationship between exertional heat illness, exertional rhabdomyolysis, and malignant hyperthermia. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1065–1069. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a9d8d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chelu MG, Goonasekera SA, Durham WJ, Tang W, Lueck JD, Riehl J, Pessah IN, Zhang P, Bhattacharjee MB, Dirksen RT, Hamilton SL. Heat- and anesthesia-induced malignant hyperthermia in an RyR1 knock-in mouse. Faseb J. 2006;20:329–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4497fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durham WJ, Aracena-Parks P, Long C, Rossi AE, Goonasekera SA, Boncompagni S, Galvan DL, Gilman CP, Baker MR, Shirokova N, Protasi F, Dirksen R, Hamilton SL. RyR1 S-nitrosylation underlies environmental heat stroke and sudden death in Y522S RyR1 knockin mice. Cell. 2008;133:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corona BT, Rouviere C, Ingalls CP. Malignant hyperthermia susceptible mice can safely perform voluntary endurance training and exhibit an enhanced intrinsic fatigue resistance. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:S593. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona BT, Rouviere C, Hamilton SL, Ingalls CP. Eccentric contractions do not induce rhabdomyolysis in malignant hyperthermia susceptible mice. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1542–1553. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90926.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingalls CP, Warren GL, Williams JH, Ward CW, Armstrong RB. E-C coupling failure in mouse EDL muscle after in vivo eccentric contractions. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:58–67. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingalls CP, Wenke JC, Nofal T, Armstrong RB. Adaptation to lengthening contraction-induced injury in mouse muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1067–1076. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01058.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corona BT, Balog EM, Doyle JA, Rupp JC, Luke RC, Ingalls CP. Junctophilin Damage Contributes To Early Strength Deficits And EC Coupling Failure After Eccentric Contractions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00365.2009. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phimister AJ, Lango J, Lee EH, Ernst-Russell MA, Takeshima H, Ma J, Allen PD, Pessah IN. Conformation-dependent stability of junctophilin 1 (JP1) and ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1) channel complex is mediated by their hyper-reactive thiols. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8667–8677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]