Abstract

Background. There is mounting evidence that dyslipidaemia may contribute to development and progression of renal disease. For instance, hyperlipidaemia in apolipoprotein E-deficient (apoE−/−) mice is associated with glomerular inflammation, mesangial expansion and foam cell formation. ApoA-1 mimetic peptides are potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds which are highly effective in ameliorating atherosclerosis and inflammation in experimental animals. Given the central role of oxidative stress and inflammation in progression of renal disease, we hypothesized that apoA-1 mimetic peptide, D-4F, may attenuate renal lesions in apoE−/− mice.

Methods. Twenty-five-month-old female apoE−/− mice were treated with D-4F (300 µg/mL in drinking water) or placebo for 6 weeks. Kidneys were harvested and examined for histological and biochemical characteristics.

Results. Compared with the control mice, apoE−/− mice showed significant proteinuria, tubulo-interstitial inflammation, mesangial expansion, foam cell formation and up-regulation of oxidative [NAD(P)H oxidase subunits] and inflammatory [NF-κB, MCP-1, PAI-1 and COX-2] pathways. D-4F administration lowered proteinuria, improved renal histology and reversed up-regulation of inflammatory and oxidative pathways with only minimal changes in plasma lipid levels.

Conclusions. The apoE−/− mice develop proteinuria and glomerular and tubulo-interstitial injury which are associated with up-regulation of oxidative and inflammatory mediators in the kidney and are ameliorated by the administration of apoA-1 mimetic peptide. These observations point to the role of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of renal disease in hyperlipidaemic animals and perhaps humans.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, hyperlipidaemia, inflammation, oxidative stress

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) results in profound dyslipidaemia, which stems largely from altered metabolism of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [1,2]. Conversely, there is mounting evidence that dyslipidaemia may contribute to the development and progression of chronic kidney disease [3–7]. For instance, several studies have shown a significant association between dyslipidaemia and deterioration of renal function in patients with pre-existing renal disease [8–10] and increased risk of renal dysfunction among individuals with elevated plasma triglycerides and reduced plasma HDL cholesterol [11] or those with type III hyperlipoproteinaemia [12].

Although the contribution of dyslipidaemia as a cardiovascular risk factor in the general population and patients with CKD is well established, its precise role in the development and progression of renal disease is unclear [5,13]. Apolipoprotein E gene inactivation (apoE−/−) in mice results in severe hyperlipidaemia, which is due to accumulation of atherogenic chylomicron and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants, resembling human type III hyperlipidaemia [14,15]. In fact, apoE−/− mice have been widely used as a model for studies of atherosclerosis [16], and several studies have shown glomerular inflammation, mesangial expansion, foam cell formation and endothelial activation in the kidneys of apoE−/− mice [17,18]. In man, renal involvement has been described in a patient with type III hyperlipoproteinaemia [16]. Therefore, apoE−/− mice provide a convenient animal model to study the effects of hyperlipidaemia on development and progression of kidney disease.

Chylomicron and VLDL remnants (which accumulate in the plasma of apoE−/− mice) are highly susceptible to oxidation. Binding and internalization of oxidized lipoproteins by mesangial cells and macrophages promote expression of adhesion molecules and monocyte chemotactic protein-1, inhibition of nitric oxide production, endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis [19,20]. These events culminate in oxidative stress, inflammation, atherosclerosis and other adverse outcomes [21,22]. In addition to facilitating clearance of the remnant lipoproteins by the liver [23], apoE is involved in cholesterol efflux from macrophages and peripheral tissues [24,25]. Furthermore, apoE plays an immune-modulatory role, and its deletion in mice leads to an inflammatory state [26]. Therefore, lipid deposition, oxidative stress and inflammation may contribute to the renal injury in this model.

Apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA-1) is the major lipoprotein constituent of HDL which mediates many of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of HDL. In addition, apoA-1 plays a critical role in HDL-induced efflux of excess cholesterol and phospholipid from peripheral tissues and their transport to the liver, a process known as reverse cholesterol transport. ApoA-1 mimetic peptides are an emerging class of therapeutic agents which utilize the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory properties and reverse cholesterol transport capacity of apoA-1 to treat atherosclerosis and inflammatory disorders. Among the existing products, the 18-amino acid peptide, 4F, has shown significant efficacy in the treatment of inflammation, oxidative stress and atherosclerosis in experimental animals. For instance, administration of 4F significantly improves HDL function in mice and monkeys [27], reduces the size and macrophage content of atherosclerotic plaques in aged mice [28,29] and improves vascular function and reduces endothelial damage in other rodents [30,31]. In addition, the use of apoA-1 mimetic peptides has been effective in a wide range of inflammatory conditions in experimental animals [32–34]. Finally, the administration of 4F ameliorates glomerulosclerosis, tubulo-interstitial injury and inflammation and reduces renal tissue lipid accumulation in the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient mice fed a Western diet [35]. The present study was undertaken to explore the effect of 4F administration on the established renal injury and the associated oxidative stress and inflammation in apoE−/− mice. Accordingly, renal histology and kidney tissue expression of several pro-inflammatory, pro-fibrosis and pro-oxidant pathways were examined in the 24-week-old wild-type mice and untreated as well as 4F-treated apoE−/− mice.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Los Angeles. Twenty-five-week-old female apoE–/– mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) fed a normal chow diet (Harlan Teklad) were randomized to D-4F-treated (n = 6) and untreated (n = 6) groups. The treatment group was administered D-4F in the drinking water (300 µg/mL) for 6 weeks starting at week 19 of their age. The choice of the given D-4F dosage was based on earlier studies which demonstrated its efficacy in mice [35]. Sex- and age-matched C57BL/6 J mice (n = 6) were used as additional controls. At the conclusion of the study, under general anaesthesia, mice were euthanized by exsanguination, and plasma and kidney were isolated. Plasma samples were processed for lipid/lipoprotein analysis. A portion of the kidneys was fixed in 10% formalin for histological evaluation. The remaining tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C for further study. Urinary albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured using Nephrat kit and Creatinine Companion kit purchased from Exocell, Inc. (Philadelphia, PA, USA). Serum cholesterol, triglyceride and creatinine were determined by AnTech Diagnostics (Irvine, CA, USA). A colorimetric assay was used to measure plasma blood urea nitrogen concentration using a kit obtained from Bioassay systems (Hayward, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Nephrat kit and serum cholesterol, triglyceride and urea concentrations were determined by AnTech Diagnostics (Irvine, CA, USA).

Tissue preparation

Kidney cortex was separated and homogenized in 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, containing 320 nmol/L sucrose, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mg/mL leupeptin, 2 mg/mL aprotinin and 1 mol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at 0°C to 4°C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min at 4°C to remove tissue debris and nuclear fragments. The supernatant was used to perform the Western blot analyses. Total protein concentration was determined with the use of a Bio-Rad kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Western blot analyses

All solutions, tubes and centrifuges were maintained at 0–4°C. The nuclear extract was prepared as described previously [36]. Briefly, 100 mg of kidney cortex was homogenized in 0.5 mL buffer A containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 µM pepstatin and 1 mM P-aminobenzamidine using a tissue homogenizer for 20 s. Homogenates were kept on ice for 15 min, and then 125 µL of a 10% Nonidet p40 (NP 40) solution was added and mixed for 15 s, and the mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 12 000 rpm. The supernatant containing cytosolic proteins was collected. The pelleted nuclei were washed once with 200 µL of buffer A plus 25 µL of 10% NP 40, centrifuged, then suspended in 50 µL of buffer B (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 50 mM KCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 10% (v/v) glycerol), mixed for 20 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 12 000 rpm. The supernatant containing nuclear proteins was stored at −80°C. The protein concentrations in tissue homogenates and nuclear extracts were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Target proteins in the cytoplasmic and/or nuclear fractions of the kidney tissue were measured by Western blot analysis using the following antibodies: rabbit antibodies against rat NF-κB p65, NOX4, MCP-1, COX-2 and COX-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against 12-lipoxygenase (12-LO) (Cayman chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ), glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) and Mn-SOD (Millipore, Billerica, MA), phospho-IκB-α (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Denver, CO), gp91phox and p47phox (BD bioscience, San Jose, CA) were purchased from the cited sources. Antibody against β-actin was purchased from Sigma Inc. (Saint Louis, MO).

Briefly, aliquots containing 50 µg proteins were fractionated on 8% and 4–20% Tris-glycine gel (Novex Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at 120 V for 2 h and transferred to Hybond-ECL membrane (Amersham Life Science Inc., Arlington Heights, IL). The membrane was incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer (1× TBS, 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat milk) and then overnight in the same buffer containing the given antibodies. The membrane was washed three times for 5 min in 1× TBS, 0.05% Tween-20 prior to 2-h incubation in a buffer (1× TBS, 0.05% Tween-20 and 3% nonfat milk) containing horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Life Science Inc.) at 1:1000 dilution. The membrane was washed four times and developed by autoluminography using the ECL chemiluminescent agents (Amersham Life Science Inc.)

Histological and immuno-histological procedures

All histological and immuno-histological evaluations were performed blindly without previous knowledge of the experimental groups. Light microscopic studies were performed in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded kidney sections stained with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Severity of glomerulosclerosis and tubulo-interstitial injury was evaluated as described in previous communications [37,38]. Avidin–biotin–peroxidase methodology was used to identify lymphocytes (CD5-positive cells) and macrophages (ED1-positive cells) as described in previously [38]. Cellular infiltration was evaluated separately in the glomeruli [positive cells per glomerular cross section (gcs)] and in tubulo-interstitial areas (positive cells per square millimeter).

Monoclonal antibodies were used to identify lymphocytes (anti-CD5 clone MRCOX19; Biosource, Camarillo, CA, USA) and macrophages (anti ED1; Harlan Bioproducts, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Secondary rat anti-mouse and donkey anti-rabbit antibodies with minimal cross-reactivity to rat serum proteins were obtained from Accurate Chemical and Scientific Co. (Westbury, NY, USA).

Determination of inflammatory index

Inflammatory index was determined for LDL, and protective capacity for HDL was determined according to previous reports [27]. In this bioassay, LDL is added to cultured human aortic endothelial cells and undergoes oxidative modification. Oxidized LDL induces monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1). The culture supernatant is tested for monocyte chemotactic activity (MCA) in a Neuroprobe chemotactic unit. In the absence of HDL, the MCA is high. In the presence of normal HDL, LDL oxidation and MCP-1 production are prevented. In the presence of dysfunctional HDL, however, the LDL oxidation is not prevented, and it is even amplified. To determine the inflammatory index, in brief, LDL and HDL were isolated from plasma using fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) equipped with Superose 6B columns. Human aortic endothelial cells were isolated from trimmings of aorta during heart transplantation and were propagated in culture. Monocytes were isolated from the blood of healthy volunteers in a bank of donors at UCLA. LDL (at 100 µg/mL) and HDL (at 15 µg/mL) together or alone were added to endothelial cultures and incubated overnight. The supernatant was removed, diluted 20 folds and tested in the MCA assay. Following the monocyte migration, the filter membranes were fixed and stained, and the number of cells in six high-power fields was determined.

Data presentation and analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE unless indicated otherwise. ANOVA and Tukey post tests for multiple groups were used in statistical evaluation of the data using SPSS software version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

General data

Data are summarized in Table 1. As expected, serum cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were markedly elevated in the apoE−/− mice as compared with the control group. In contrast, HDL cholesterol and paraoxonase activity were significantly reduced, and urinary protein excretion was increased in apoE−/− mice. Treatment with 4F resulted in a significant reduction in the urinary protein excretion and a significant rise in plasma paraoxonase activity. However, 4F administration did not significantly change plasma cholesterol and only minimally but significantly raised HDL-cholesterol concentrations.

Table 1.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), urine protein/creatinine concentration ratio (Prot/creat) and plasma total cholesterol (chol), triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol concentrations and paraoxonase activity in the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice

| Control | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/− + 4F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25.5 ± 1.8 | 28.1 ± 0.1 | 26.1 ± 0.4 |

| Urine Prot/creat | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.04* | 2.4 ± 0.2**** |

| chol (mg/dL) | 87.5 ± 6.8 | 573.6 ± 26.6** | 522.4 ± 28.8 |

| triglyceride (mg/dL) | 70.1 ± 9.0 | 166.4 ± 10.4** | 150.6 ± 12.3 |

| HDL-chol (mg/dL) | 46.2 ± 4.2 | 27.8 ± 0.6* | 32 ± 1.4*** |

| PON activity | 71.1 ± 5.1 | 24.2 ± 0.9** | 31.4 ± 1.9*** |

n = 6 in each group.

P < 0.05 apoE−/− vs CTL mice.

P < 0.005 apoE−/− vs CTL mice.

P < 0.05 D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE−/− mice.

P < 0.005 D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE−/− mice.

Histological findings

The apoE−/− mice exhibited mesangial expansion and hypercellularity, occasional capillary microthrombi and foam cell accumulation (Figure 1). These abnormalities were associated with increased interstitial T-cell and macrophage infiltration (Figure 2). Treatment with 4F for 6 weeks significantly improved glomerular and interstitial macrophage and T-cell infiltration (Figure 3).

Fig. 1.

Representative photomicrographs of glomeruli from an untreated apoE-deficient mouse showing capillary occlusion by microthrombi (arrowhead) and mesangiolysis with capillary dilatation (asterisk) (A) and mild mesangial expansion, collapsed glomerulus with foam cells (asterisks) and focal infiltration of inflammatory cells in the adjacent tubulo-interstitial region (arrowhead) (B). (PAS staining, original magnification ×400).

Fig. 2.

Representative photomicrographs illustrating the contrasting features of renal biopsies of an untreated apoE-deficient mouse (A, B) and D-4F-treated apoE-deficient mouse (C, D). Infiltrating macrophages are present in A (arrows) and absent in C (immuno-peroxidase staining). Mesangial expansion and foam cells (asterisks) in B are absent in the glomerulus in D that shows normal appearance (PAS staining) (original magnification ×400).

Fig. 3.

Bar graphs depicting macrophage and lymphocyte infiltration in the glomeruli and tubulo-interstitial regions of the kidney in the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice. The untreated apoE-deficient mice showed macrophage and lymphocyte accumulation in glomeruli and tubulointerstitium that was suppressed by treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.005.

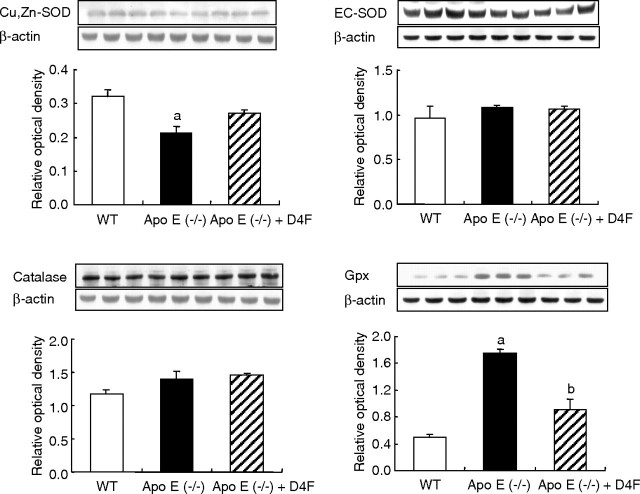

NAD(P)H oxidase and antioxidant enzymes

Data are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Compared with the wild-type mice, kidney tissue in the untreated apoE−/− mice exhibited significant up-regulation of the catalytic (NOX-4, gp91phox), and regulatory (p47phox) subunits of the superoxide-producing enzyme, NAD(P)H oxidase. Treatment with 4F significantly reduced p47phox abundance but failed to alter NOX-4 or gp91phox abundance. Despite up-regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-producing NAD(P)H oxidase isoforms, Cu/Zn-SOD abundance in the kidney tissue was unchanged in the apoE−/− mice and was significantly increased with 4F therapy. Renal tissue catalase and EC-SOD abundance were similar among the apoE−/− and wild-type groups and were not affected by 4F therapy. Glutathione peroxidase abundance was significantly increased in the untreated apoE−/− group and was reduced by D-4F administration.

Fig. 4.

Representative Western blots and group data depicting protein abundance of the NAD(P)H oxidase subunits (NOX-4, gp91phox and p47phox) in the renal tissues of the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice. n = 6 in each group. a: P < 0.05 vs control group, b: P < 0.05, D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE-deficient group.

Fig. 5.

Representative Western blots and group data depicting protein abundance of the CuZn-SOD, extracellular SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) in the renal tissues of the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice. n = 6 in each group. a: P < 0.05 vs control group, b: P < 0.05, D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE-deficient group.

Phospho-IkB, COX-2, MCP-1 and PAI-1 data

Data are shown in Figures 6 and 7. Compared with the wild-type mice, kidney tissues from the untreated apoE−/− mice showed a significant increase in Phospho-IkB and a significant increase in nuclear translocation of p65 subunits of NF-κB. These observations point to activation of NF-κB, which is the general transcription factor for various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Treatment with 4F significantly attenuated but did not fully reverse NF-κB activation in the kidneys of the apoE−/− mice. Compared with the control group, kidney tissues in the untreated apoE−/− mice showed significant up-regulation of COX-2. Administration of 4F resulted in significant reduction of COX-2 abundance in the kidneys of apoE−/− mice. Likewise, kidney tissue MCP-1 and PAI-1 were significantly increased in the untreated apoE−/− compared with the wild-type mice and were lowered by 4F administration. Kidney tissue abundance of COX-1 and 12-LPO was similar among the wild-type and apoE−/− mice and was unaffected by 4F administration.

Fig. 6.

Representative Western blots and group data depicting protein abundance of phospho-IκB and nuclear p65 active subunit of NF-κB in the renal tissues of the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice. n = 6 in each group. a: P < 0.05 vs control group, b: P < 0.05, D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE-deficient group.

Fig. 7.

Representative Western blots and group data depicting protein abundance of MCP-1, PAI-1, COX-1, COX-2 and 12-lipoxygenase (12-LPO) in the renal tissues of the wild-type (control) and untreated and D-4F-treated apoE−/− mice. n = 6 in each group. a: P < 0.05 vs control group, b: P < 0.05, D-4F-treated vs untreated apoE-deficient group.

LDL and HDL chemotactic activities

Data are illustrated in Figure 8. LDL from the apoE-deficient mice showed significantly higher inflammatory index compared with those from wild-type mice (Figure 8), and HDL from apoE-deficient mice was significantly less protective against LDL oxidation by endothelial cells as compared with HDL from wild-type mice. This effect was more pronounced when autologous LDL (prepared from apoE-deficient animals vs standard LDL obtained from healthy human donors) was used in incubation with cultured endothelial cells. D-4F treatment resulted in significant improvements in the inflammatory index of LDL and in the protective capacity of HDL against LDL oxidation and MCP-1 induction (Figure 8).

Fig. 8.

Bar graphs depicting LDL and HDL chemotactic activities in the wild-type and untreated- and D-4F-treated apoE−/− groups. Standard LDL and standard HDL were from healthy donors were used as controls. Mouse LDL and HDL were isolated from plasma by FPLC and inflammatory index determined in the as described in the Methods section. The values are presented as mean ± SD of migrated monocytes per high power field. The value for the standard LDL was taken as 1.0 and used as basis against which the inflammatory indices of the test samples were calculated. n = 6 in each group.

Discussion

As expected, the apoE−/− mice employed in the present study exhibited severe hyperlipidaemia. This was associated with significant proteinuria, foam cell formation, occasional glomerular capillary thrombosis and significant glomerular and tubulo-interstitial macrophage and lymphocyte accumulation. These observations are consistent with the findings reported in earlier studies in this model [17,18]. Proteinuria and renal histological abnormalities were accompanied by marked up-regulation of oxidative and inflammatory pathways in the kidneys of the apoE−/− mice. Accordingly, kidneys in apoE−/− animals showed marked up-regulation of NOX-4, gp91phox and p47phox subunits of NAD(P)H oxidase isoforms which are the major source of superoxide (O2−) in the kidney and cardiovascular tissues. Despite up-regulation of the superoxide-production capacity, renal tissue abundance of Cu/Zn-SOD was reduced, and extracellular SOD abundance was unchanged in the apoE−/− mice kidneys. These events can contribute to oxidative stress and renal injury in the apoE−/− mice. Administration of 4F for 6 weeks resulted in partial but significant reduction of NADPH oxidase subunits and restoration of Cu/Zn-SOD. These observations point to the efficacy of this peptide in improving redox status of the kidney in the apoE−/− mice.

The apoE−/− mice exhibited a significant increase in the renal tissue abundance of MCP-1 which is a potent pro-inflammatory chemokine. This phenomenon can contribute to renal injury and dysfunction by promoting inflammation and leukocyte infiltration seen here as well as in earlier studies [17,18]. Similarly, PAI-1 expression was significantly increased in the kidneys of the apoE−/− animals. This can, in turn, contribute to thrombosis, glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis by inhibiting plasmin and matrix metalloproteinases. Up-regulation of MCP-1, PAI-1 and NAD(P)H oxidase and immune cell infiltration in the kidneys of apoE−/− mice were accompanied by activation of NF-κB as evidenced by elevation of Phospho-IkB and nuclear translocation of P65 active subunit of this transcription factor. NF-κB is the general transcription factor for numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and as such its activation can account for the up-regulation of MCP-1 and PAI-1 and immune cell infiltration in the kidneys of the apoE−/− animals shown here and in previous studies [17,18]. Administration of 4F attenuated NF-κB activation, reduced MCP-I and PAI-I abundance and lowered glomerular and interstitial immune cell infiltration in the apoE−/− mice.

By-products of the main enzymes of the arachidonic acid metabolism play an important part in the pathogenesis of inflammation and oxidative stress as well as dysregulation of renal and systemic haemodynamics [39–43]. For instance, COX-2 can promote ROS production, inflammation and haemodynamic alterations in the kidney and other tissues [39–42,44–46]. Consequently, the observed up-regulation of renal tissue COX-2 abundance in our apoE−/− mice can contribute to renal injury and inflammation in these animals. Treatment with 4F significantly reduced COX-2 expression and meliorated oxidative stress and inflammation in the apoE−/− mice. This was accompanied by a significant attenuation of proteinuria and nephropathological abnormalities in these animals.

The results of the present study provide compelling evidence that severe persistent hyperlipidaemia in apoE−/− mice results in renal injury, which is marked by oxidative stress, inflammation, mesangial expansion and microvascular thrombosis. These observations support the potential role of long-standing hyperlipidaemia in the pathogenesis of renal disease. Administration of apoA-1 mimetic peptide, 4F, attenuated up-regulation of oxidative and inflammatory mediators, reversed proteinuria and ameliorated histological changes in the kidneys of apoE−/− mice. Since the treatment had only minimal impact on plasma lipid levels, these observations suggest that the associated renal disease in this model is largely mediated by oxidative stress and inflammation as opposed to a direct effect of elevated plasma lipid levels per se.

The apoA-1 mimetic peptides, which were originally designed to improve HDL function [27,28], have been found to possess profound antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [32–35]. In this context, 4F has been shown to significantly reduce LDL pro-inflammatory activity and enhanced HDL anti-inflammatory activity in human uraemic plasma [47]. Thus, the renal protective effect of 4F observed in apoE−/− mice appears to be mediated by its potent antioxidant/anti-inflammatory actions. In fact, in the present study, LDL from the apoE-deficient mice was less resistant to oxidative modification and induced a higher level of monocyte chemotactic activity by cultured endothelial cells when compared with LDL from the wild-type mice which is resistant to inflammatory pressure. Treatment of the animals with D-4F resulted in normalization of LDL resistance to oxidative modification. Similarly, HDL from the apoE-deficient mice was less protective against LDL oxidation when compared with the HDL from the wild-type animals. Treatment with D-4F normalized the protective capacity of HDL. Pro-inflammatory properties of LDL and HDL are primarily mediated by their oxidized lipid contents. In fact, in an earlier study, our coauthors have demonstrated that plasma lipoprotein fractions in apoE−/− mice contain large quantities of lipoperoxides which are dramatically reduced by D-4F administration [28]. Therefore, the observed improvement in the LDL and HDL inflammatory activities shown here can be in part due to the antioxidant properties of this peptide.

In conclusion, severe persistent hyperlipidaemia in apoE-deficient mice results in up-regulation of oxidative and inflammatory mediators in the kidney culminating in proteinuria and glomerular and tubulo-interstitial injury. Administration of apoA-1 mimetic peptide 4F attenuates up-regulation of oxidative and inflammatory mediators and improves proteinuria and renal histological abnormalities without altering plasma lipid profile. These observations suggest that the hyperlipidaemia-associated renal disease is primarily mediated by oxidative stress and inflammation as opposed to direct effect of elevated plasma lipid levels per se.

Acknowledgments

H.M. is supported by the NIH-NRSA Award No DK-082130. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or in part, except in abstract format.

Conflict of interest statement. M.N. and A.M.F. are principals in BruinPharma Inc.

References

- 1.Vaziri ND. Dyslipidemia of chronic renal failure: the nature, mechanisms and potential consequences. Am J Physiol, Renal Physiol. 2006;290:262–272. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00099.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaziri ND. Causes of dysregulation of lipid metabolism in chronic renal failure. Semin Dial. 2009;22:644–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attman PO, Alaupovic P, Samuelsson O. Lipoprotein abnormalities as a risk factor for progressive nondiabetic renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 1999;71:14–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.07104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cases A, Coll E. Dyslipidemia and the progression of renal disease in chronic renal failure patients. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;99:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalrymple LS, Kaysen GA. The effect of lipoproteins on the development and progression of renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:723–731. doi: 10.1159/000127980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keane WF. The role of lipids in renal disease: future challenges. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;75:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ, Moradi H, Vaziri ND. Renal mass reduction results in accumulation of lipids and dysregulation of lipid regulatory proteins in the remnant kidney. Am J Physiol, Renal Physiol. 2009;296:1297–1306. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90761.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appel G. Lipid abnormalities in renal disease. Kidney Int. 1991;39:169–183. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuelson O, Mulec H, Knight-Gibson C, et al. Lipoprotein abnormalities are associated with increased rate of progression of human chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1908–1915. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.9.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunsicker LG, Adler S, Caggiula A, et al. Predictors of the progression of renal disease in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1908–1919. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntner P, Coresh J, Smith C, et al. Plasma lipids and risk of developing renal dysfunction: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Kidney Int. 2000;58:293–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amatruda JM, Margolis S, Hutchins GM. Type 3 hyperlipoproteinemia with mesangial foam cells in renal glomeruli. Arch Pathol. 1974;98:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majumdar A, Wheeler DC. Lipid abnormalities in renal disease. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:178–182. doi: 10.1177/014107680009300406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghiselli G, Schaefer EJ, Gascon P, et al. Type III hyperlipoproteinemia associated with apolipoprotein E deficiency. Science. 1981;214:1239–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.6795720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 1992;71:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90362-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zadelaar S, Kleemann R, Verschuren L, et al. Mouse models for atherosclerosis and pharmaceutical modifiers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1706–1721. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen M, Segerer S, Dantas M, et al. Renal injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2002;82:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000022222.03120.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruneval P, Bariéty J, Bélair MF, et al. Mesangial expansion associated with glomerular endothelial cell activation and macrophage recruitment is developing in hyperlipidaemic apoE null mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2099–2107. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D, Mehta JL. Antisense to LOX-1 inhibits oxidized LDL-mediated upregulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and monocyte adhesion to human coronary artery endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;101:2889–2895. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D, Mehta JL. Upregulation of endothelial receptor for oxidized LDL (LOX-1) by oxidized LDL and implications in apoptosis of human coronary artery endothelial cells: evidence from use of antisense LOX-1 mRNA and chemical inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1116–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cominacini L, Pasini AF, Garbin U, et al. Oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) binding to ox-LDL receptor-1 in endothelial cells induces the activation of NF-kappaB through an increased production of intracellular reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12633–12638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta JL, Chen J, Hermonat PL, et al. Lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1): a critical player in the development of atherosclerosis and related disorders. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahley RW, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E: from atherosclerosis to Alzheimer’s disease and beyond. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:207–217. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langer C, Huang Y, Cullen P, et al. Endogenous apolipoprotein E modulates cholesterol efflux and cholesteryl ester hydrolysis mediated by high-density lipoprotein-3 and lipid-free apolipoproteins in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Mol Med. 2000;78:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s001090000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahley RW, Rall SC., Jr Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2000;1:507–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Raines EW. Are suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins recently identified in atherosclerosis possible therapeutic targets? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Hama S, et al. D-4F and statins synergize to render HDL anti-inflammatory in mice and monkeys and cause lesion regression in old apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1426–1432. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000167412.98221.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Oral D-4F causes formation of pre-b high-density lipoprotein and improves high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation. 2004;109:3215–3220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134275.90823.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Chyu KY, Faria Neto JR, et al. Differential effects of apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide on evolving and established atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation. 2004;110:1701–1705. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142857.79401.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ou J, Ou Z, Jones DW, et al. L-4F, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic, dramatically improves vasodilation in hypercholesterolemia and sickle cell disease. Circulation. 2003;107:2337–2341. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070589.61860.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ou J, Wang J, Xu H, et al. Effects of D-4F on vasodilation and vessel wall thickness in hypercholesterolemic LDL receptor-null and LDL receptor/apolipoprotein A-I double-knockout mice on Western diet. Circ Res. 2005;97:1190–1197. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190634.60042.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Nayak DP, et al. High-density lipoprotein loses its anti-inflammatory properties during acute influenza A infection. Circulation. 2001;103:2283–2288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.18.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charles-Schoeman C, Banquerigo ML, Hama S, et al. Treatment with an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic peptide in combination with pravastatin inhibits collagen-induced arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Fogelman AM. The effect of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in inflammatory disorders other than atherosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buga GM, Frank JS, Mottino GA, et al. D-4F reduces EO6 immuno-reactivity, SREBP-1c mRNA levels, and renal inflammation in LDL receptor-null mice fed a Western diet. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:192–205. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700433-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakurai H, Hisada Y, Ueno M, et al. Activation of transcription factor NF-κB in experimental glomerulonephritis in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1316:132–138. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(96)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Ferrebuz A, et al. Evolution of renal interstitial inflammation and NF-kB activation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:587–594. doi: 10.1159/000082313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, et al. Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol, Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F191–F201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0197.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng HF, Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in cultured cortical thick ascending limb of Henle increases in response to decreased extracellular ionic content by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms: role of p38-mediated pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45638–45643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaziri ND, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Mechanisms of disease: oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:582–593. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goncalves AR, Fujihara CK, Mattar AL, et al. Renal expression of COX-2, ANG II, and AT1 receptor in remnant kidney: strong renoprotection by therapy with losartan and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:945–954. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00238.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer BK, Kammerl MC, Komhoff M. Renal cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2): physiological, pathophysiological, and clinical implications. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2004;27:43–62. doi: 10.1159/000075811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ota T, Takamura T, Ando H, et al. Preventive effect of cerivastatin on diabetic nephropathy through suppression of glomerular macrophage recruitment in a rat model. Diabetologia. 2003;46:843–851. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy MA, Adler SG, Kim YS, et al. Interaction of MAPK and 12-lipoxygenase pathways in growth and matrix protein expression in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol, Renal Physiol. 2002;283:985–994. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00181.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiritoshi S, Nishikawa T, Sonoda K, et al. Reactive oxygen species from mitochondria induce cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human mesangial cells: potential role in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2003;52:2570–2577. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komers R, Lindsley JN, Oyama TT, et al. Effects of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition on plasma and renal renin in diabetes. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;140:351–357. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.128551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaziri ND, Moradi H, Pahl MV, et al. In vitro stimulation of HDL anti-inflammatory activity and inhibition of LDL pro-inflammatory activity in the plasma of patients with end-stage renal disease by an apoA-1 mimetic peptide. Kidney Int. 2009;76:437–344. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]