Abstract

The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) is a transmembrane glycoprotein comprising two extracellular α subunits and two β subunits with tyrosine kinase activity. The IGF-1R is frequently upregulated in cancers, and signals from the cell surface to promote proliferation and cell survival. Recent attention has focused on the IGF-1R as a target for cancer treatment. Here we report that the nuclei of human tumor cells contain IGF-1R, detectable using multiple antibodies to α- and β- subunit domains. Cell surface IGF-1R translocates to the nucleus following clathrin-mediated endocytosis, regulated by IGF levels. The IGF-1R is unusual among transmembrane receptors that undergo nuclear import, in that both α and β subunits traffic to the nucleus. Nuclear IGF-1R is phosphorylated in response to ligand, and undergoes IGF-induced interaction with chromatin, suggesting direct engagement in transcriptional regulation. The IGF-dependence of these phenomena indicate a requirement for the receptor kinase, and indeed IGF-1R nuclear import and chromatin binding can be blocked by a novel IGF-1R kinase inhibitor. Nuclear IGF-1R is detectable in primary renal cancer cells, formalin-fixed tumors, preinvasive lesions in the breast, and non-malignant tissues characterized by a high proliferation rate. In clear cell renal cancer, nuclear IGF-1R is associated with adverse prognosis. Our findings suggest that IGF-1R nuclear import has biological significance, may contribute directly to IGF-1R function, and may influence the efficacy of IGF-1R inhibitory drugs.

Introduction

The IGF-1R mediates proliferation and cell survival, and is recognized as an attractive cancer treatment target (1). Following co-translational insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as a 220kDa proreceptor, the IGF-1R is cleaved in the trans-Golgi network to generate mature α (135kDa) and β (98kDa) subunits linked by disulfide bonds (2). After trafficking to the plasma membrane, IGF-1Rs are activated by IGFs, and then internalized and degraded, or recycled to the cell surface (3, 4). While other receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are known to undergo nuclear translocation (5-8), nuclear IGF-1R has not been reported in human cancers, although was detected in hamster kidney cells (9). Building on our studies of IGF signaling in prostate and renal cell cancer (RCC) (10-13), we hypothesized that the IGF-1R undergoes nuclear translocation in these tumors.

Methods

Human DU145 prostate cancer, 786-0/EV (RCC) and MCF7 (breast cancer) cells were from Cancer Research UK (CRUK; Hertfordshire UK). IGF-1R null murine fibroblasts (R− cells) and isogenic R+ cells expressing human IGF-1R were from Renato Baserga (Philadelphia, US). Primary RCC cultures were generated by disaggregation of fresh tumors, and stained for pancytokeratin (Abcam, Cambridge UK). Cells were transfected with IGF-1R (#SI00017521), caveolin (#SI00027720), or control (#1022076) siRNAs (Qiagen, Crawley UK) using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Paisley UK). IGF-1R antibody MAB391 was from R&D Systems (Abingdon UK). AZ12253801 (from Elizabeth Anderson, AstraZeneca UK), is an ATP-competitive IGF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor that show ~10-fold selectivity over the insulin receptor (IR). IC50 values for inhibition of IGF-1R and IR phosphorylation in vitro are 2.1nM and 19 nM respectively. The IC50 for inhibition of IGF-1R-driven proliferation in 3T3 mouse fibroblasts transfected with human IGF-1R is 17nM, whereas the IC50 for EGFR-driven proliferation is 440nM. AZ12253801 has been tested against a wide range of other relevant kinases, where IC50s are generally >1μM or the compound has little or no inhibitory activity at 10μM.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured in complete medium, or serum-starved overnight and treated with long-R3 IGF-I (SAFC Biosciences, Andover UK), IGF-II, insulin (Sigma-Aldrich) or solvent. Some cultures were pre-treated with solvent (DMSO), 300nM dibenzazepine (DBZ; Calbiochem, Nottingham UK), 300μM dansylcadaverine (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham UK), 30μM dynasore (Sigma-Aldrich), or AZ12253801. Immunostaining used antibodies to IGF-1Rβ carboxy-terminus (#3027, Cell Signaling Technology, CST), IGF-1Rβ amino-terminus (H-60, Santa Cruz), IGF-1Rα (24-31 from Ken Siddle, Cambridge UK, or αIR3, #GR11L, Calbiochem), calnexin, nucleolin or RNA polymerase II (Abcam). Images were acquired on a LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City UK). Photomicrographs show mid-slice confocal images through the nucleus, ×63 magnification unless stated otherwise. Fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ software in 20-30 cells for each condition, and statistical analysis utilized GraphPad Prism v5.

Cell fractionation, immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation

Whole cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer (14). Nuclear extraction used Nuclear Extraction reagents (Panomics, CA), to disrupt cells in hypotonic Buffer A, and release nuclear proteins with Buffer B (high salt with detergent). Whole cell, non-nuclear and nuclear fractions and chromatin extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for IGF-1Rα (Santa Cruz), IGF-1Rβ (CST), phosphorylated IGF-1R (Y1135-6, CST), lamin, calnexin (Abcam), golgin-84 (BD Biosciences), EpCAM (clone AUA1, CRUK), β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and Hes1 (gift of Dr. Tatsuo Sudo, Kamakura, Japan). Extracts were immunoprecipitated with IGF-1Rβ antibody (#3027, CST) or rabbit IgGs (Sigma-Aldrich); see Supplementary Information.

Immunohistochemistry

Human tissue was used under National Research Ethics studies 04/Q1606/96, 07/H0606/120 and 09/H0606/5. Formalin-fixed whole mount and tissue microarray (TMA) sections were immunostained for IGF-1R -β (#3027, CST) and -α (24-31). IGF-1R intensity and distribution were scored as described (10, 13, 15). Contingency tables were analysed using Pearson’s Chi-square test to assess relationships between IGF-1R and clinical parameters. Survival was measured from nephrectomy to death or last follow-up, and survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Prognostic factors were evaluated in multivariate analyses by Cox proportional hazards regression. These analyses used the STATA package v11.0 (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA).

Results and Discussion

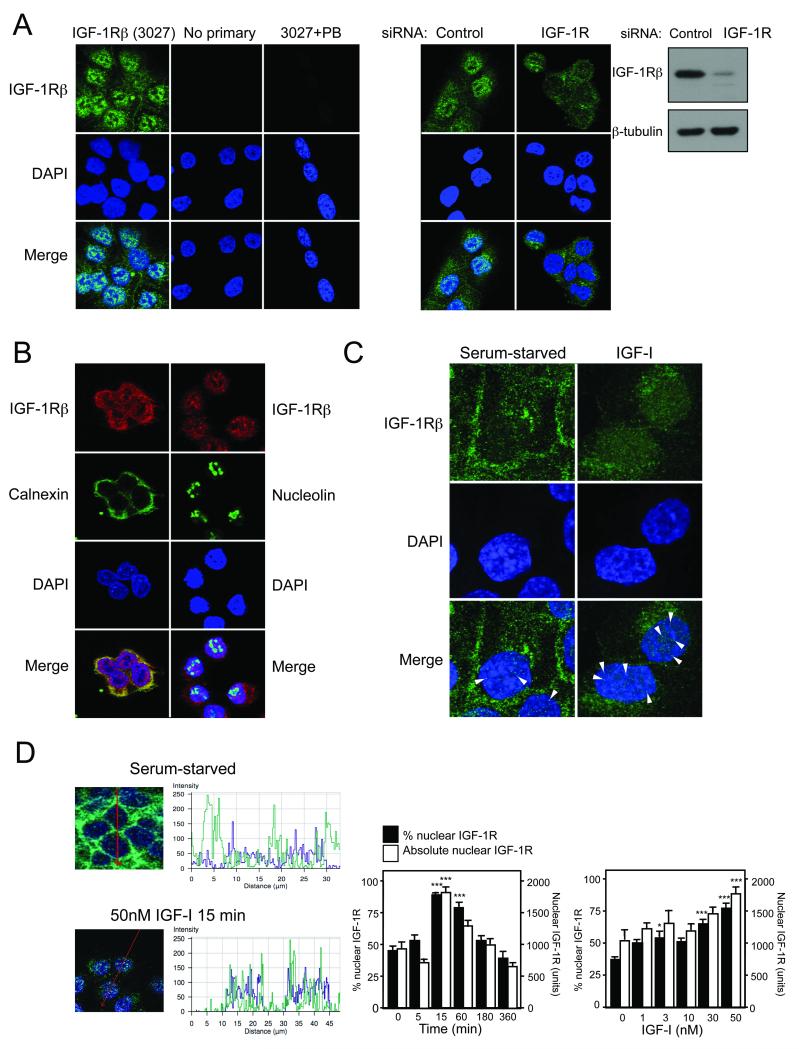

We hypothesized that the IGF-1R undergoes nuclear import, and indeed could detect intracellular IGF-1R in prostate cancer (Figure 1A), RCC and breast cancer cells (Figure S1). Intracellular IGF-1R was attenuated by IGF-1R gene silencing, was not wholly attributable to receptor within ER, and appeared to overlie the nucleus, sparing the nucleoli (Figure 1A, B). Detection of nuclear receptor was unrelated to IGF-1R levels per se: IGF-1R-overexpressing R+ cells contained negligible nuclear IGF-1R (Figure S1). Nuclear translocation of other RTKs can involve import of full-length receptor, or enzymatic release of receptor intracellular domains (ICDs), each process initiated when receptor is engaged by ligand (5, 7, 8). We found that serum-starved cells showed prominent membrane IGF-1R that diminished with IGF-I treatment (Figure 1C), consistent with receptor internalization and degradation (3). Persisting IGF-1R showed evidence of nuclear accumulation 15-60 minutes after addition of 30-50nM IGF-I (Figures 1C, D, S2). IGF-1R nuclear import was also enhanced by IGF-II, but only modestly by insulin, correlating with the magnitude of ligand-induced receptor phosphorylation (Figure S3), and with the known affinity of these ligands for IGF-1R (2).

Figure 1. IGF-I induces IGF-1R nuclear translocation in human tumor cells.

A) IGF-1Rβ immunofluorescence in DU145 cells cultured in complete medium. IGF-1R signal was attenuated by IGF-1R depletion (confirmed in immunoblot to right). B) DU145 cells co-stained for IGF-1R and calnexin or nucleolin. C) Serum-starved DU145 cells were treated with solvent or IGF-I (50nM, 15min), and IGF-1Rβ stained as A. Arrowheads: examples of punctate nuclear IGF1R. Original magnification ×100. D) Left: DU145 cells were serum-starved or IGF-treated (50nM, 15 min), and stained for IGF1Rβ and DAPI. Merged images; arrow shows path along which intensity of IGF-1R (green) and DAPI (blue) is quantified. Center panels: IGF-1R overlying DAPI registers ~50 arbitrary units in starved cells (upper), 100-150 units after IGF-I (lower). Right: quantification of nuclear IGF-1R, following 50nM IGF-I for 0-360min (left), 0-50nM IGF-I for 15min (right). Black columns: mean % nuclear IGF-1R; white: mean absolute nuclear IGF-1R (arbitrary units); bars: SEM (n=20-30 cells). Compared with serum-starved cells, nuclear IGF-1R signal was enhanced by IGF-I (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001).

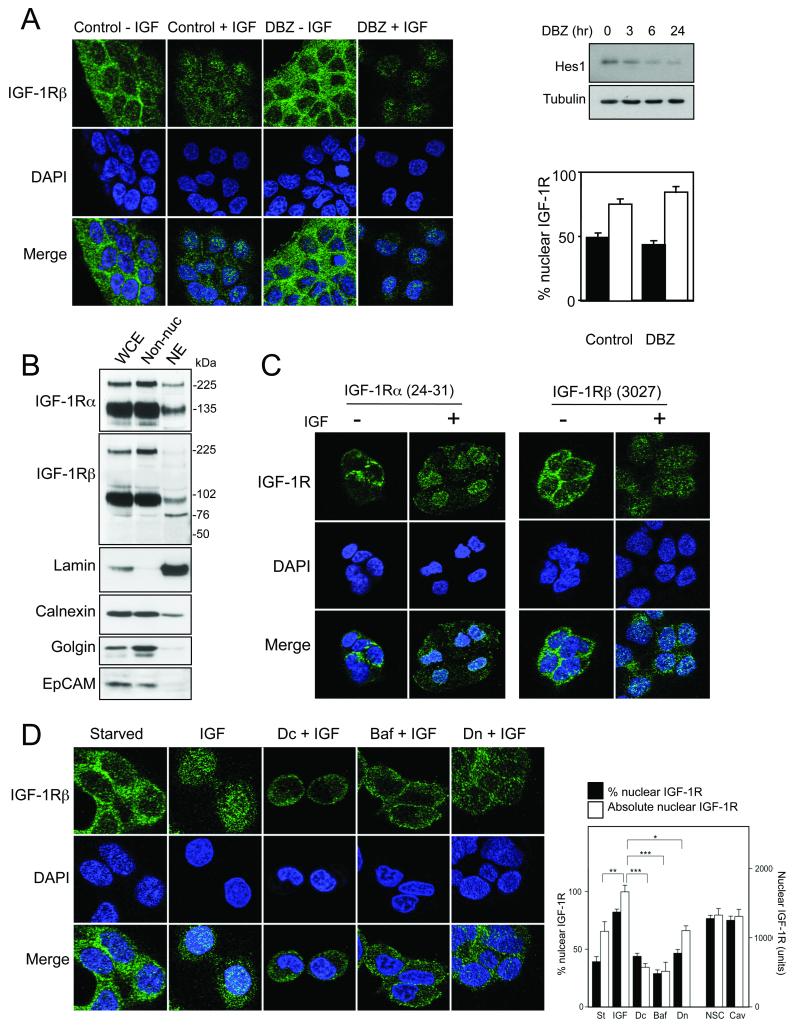

The IGF-1R β-subunit is reportedly a substrate for γ-secretase, liberating 50-52 kDa ICDs in R+ cells (16). However, IGF-1R distribution was unaffected by γ-secretase inhibition in prostate cancer cells (Figure 2A), and we detected full-length IGF-1R α and β in nuclear extract (Figure 2B). Furthermore, nuclear IGF-1R was detectable using antibodies to β-subunit extracellular domain (Figure S4A) and α-subunit, which also showed IGF-induced nuclear accumulation (Figures 2C, S4B). Therefore, our data do not support γ-secretase-dependent cleavage, but instead suggest a model in which full-length IGF-1R translocates to the nucleus. Other full-length receptors known to undergo nuclear translocation are monomers (5, 8); to our knowledge, IGF-1R is the only example of a receptor that traffics as multiple subunits to the nucleus.

Figure 2. Full-length IGF-1R α and β subunits undergo nuclear import following clathrin-dependent endocytosis.

A) DU145 cells were treated with DBZ (300nM, 6hr) and in final 15min with 50nM IGF-I. Graph: mean % nuclear IGF-1R in serum-starved (black columns) or IGF-treated cells (white); bars: SEM. Immunoblotting (upper right) confirmed DBZ bioactivity in inhibiting expression of Notch target Hes1. B) DU145 whole cell extract (WCE), non-nuclear components (Non-nuc) and nuclear extract (NE) immunoblotted for IGF-1R, lamin (nucleus), calnexin (ER), golgin-84 (Golgi), and EpCAM (plasma membrane). C) Serum-starved DU145 cells were treated with solvent or IGF-I (50nM, 15min) and stained for IGF-1R -α or -β. D) Serum-starved DU145 cells were treated for 4hr with dansylcadaverine (Dc), bafilomycin A1 (Baf), or dynasore (Dn) and in the final 15min with 50nM IGF-I. Absolute nuclear IGF-1R was enhanced by IGF-I (*p<0.01) and inhibited by Dc, Baf and Dn (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001). Figure S5A shows images of IGF-treated cells following caveolin-1 depletion.

The IGF-1R undergoes both caveolin and clathrin -mediated endocytosis (4, 17). Consistent with the contribution of the latter to EGFR nuclear import (5, 18), nuclear IGF-1R translocation was inhibited by dansylcadaverine (p<0.001) and the dynamin-1 inhibitor dynasore (p<0.05), inhibitors of clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and by bafilomycin A1 (p<0.001), which blocks endosomal acidification, but not by caveolin-1 depletion (Figures 2D, S5). Post-endosomal EGFR trafficking involves translocation to the ER, removal from the lipid bilayer by association with a component of the Sec61 translocon (6), and nuclear import in complex with importins (5, 18). The IGF-1R lacks a canonical nuclear localization sequence, and we could not detect binding to importin-β (not shown). Neither was there evidence of interaction between nuclear IGF-1R and the adaptor protein insulin-receptor substrate-1, which can undergo nuclear import (19), but is predominantly cytoplasmic in DU145 cells (not shown). While our manuscript was under review, Sehat and colleagues reported that the IGF-1R undergoes nuclear translocation, and demonstrated that this is regulated by SUMOylation, not previously known to influence RTK localization (20).

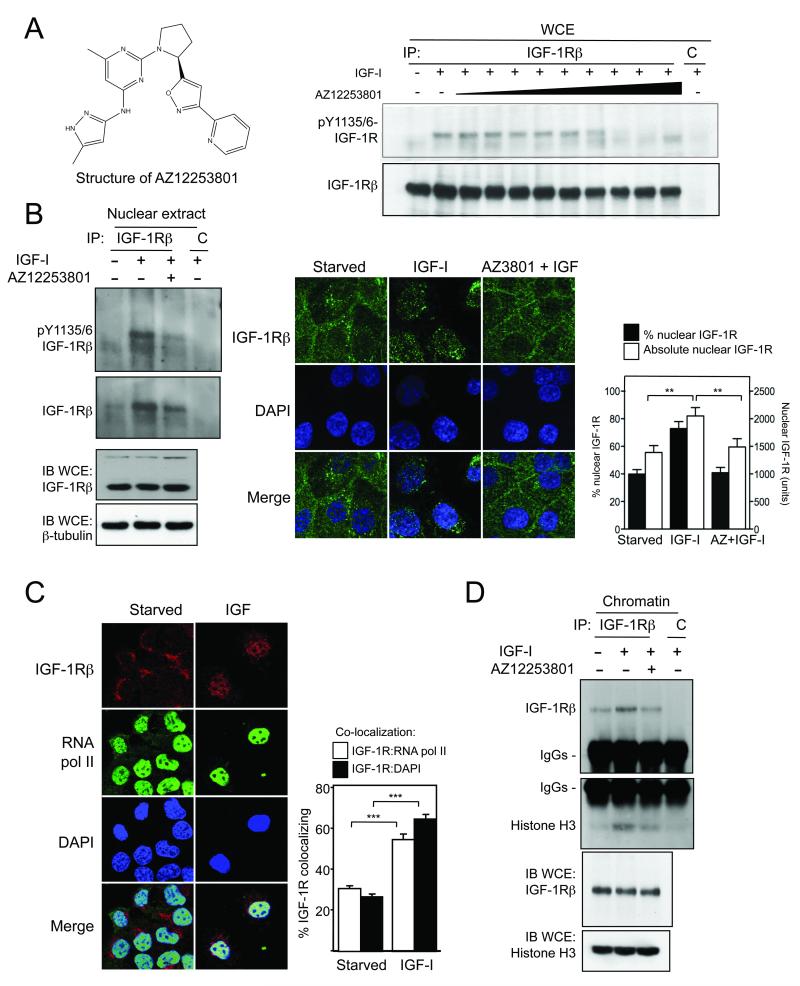

We noted that IGFs and insulin induced IGF-1R nuclear import in proportion to their ability to activate the receptor, and nuclear IGF-1Rβ was phosphorylated in response to ligand (Figures S3, S6). Therefore we interrogated the contribution of the IGF-1R kinase to nuclear translocation, utilizing two classes of IGF-1R inhibitor: blocking antibody MAB391, and AZ1225380, a selective inhibitor of the IGF-1R kinase (Figures 3A, S6). Equimolar concentrations of each agent inhibited IGF-1R activation, and consistent with previous findings (21), MAB391 down-regulated whole cell IGF-1R. In whole cell extracts and in the nuclear compartment, IGF-1R phosphorylation was more profoundly inhibited by AZ12253801 than MAB391 (Figure S6C). Pre-treatment with AZ12253801 at its IC50 for proliferation not only blocked nuclear IGF-1R phosphorylation, but also inhibited IGF-1R nuclear import, shown by immunoprecipitation from nuclear extract, and confocal microscopy (Figure 3B). These data indicate that IGF-1R kinase activity is required for IGF-1R to enter the nucleus. This information may have therapeutic relevance: aside from the challenge of crossing membranes, antibodies may be limited by their size from entering the nucleus in complex with IGF-1R (22); we speculate that nuclear IGF-1R activity may be more effectively blocked by small molecule inhibitors. In considering potential functions of the receptor in this newly-identified location, we observed that the distribution of nuclear IGF-1R was reminiscent of the speckled pattern characteristic of components of the transcriptional machinery (23). Furthermore, we noted (Figure 2C) that punctate nuclear IGF-1R was located principally in less dense regions of DNA, potentially more accessible to transcription factors. Indeed we could detect IGF-induced co-localization with RNA polymerase II (Figure 3C), and binding to chromatin shown by co-precipitation with histone H3 (Figure 3D). This suggests a direct role for the IGF-1R in transcriptional regulation, consistent with the recent report of Sehat et al (20), and with the known function of other nuclear RTKs (5, 7).

Figure 3. IGF-1R nuclear import and chromatin binding are blocked by IGF-1R inhibition.

A) Left: structure of AZ12253801. Right: serum-starved DU145 cells treated with 50nM IGF-I in final 15min of 1hr incubation with 0.1-100nM AZ12253801. IGF-1Rβ or control (C) immunoprecipitates probed for phospho- and total IGF-1Rβ Figure S6 shows quantification of these results, and effects on clonogenic survival. B) DU145 cells treated with 50nM IGF-I in final 30min of 6hr incubation with 120nM AZ12253801. Left: nuclear extracts immunoprecipitated with control (C) or IGF-1Rβ antibody, and probed for phospho- and total IGF-1Rβ Right: parallel cultures imaged for IGF-1Rβ. IGF-induced nuclear IGF-1R import was inhibited by AZ12253801 (p<0.001 for % nuclear signal, **p<0.01 for absolute nuclear signal). C) Serum-starved and IGF-treated cells were co-stained for IGF-1Rβ (red) and RNA polymerase II (green). IGF-I enhanced co-localization of IGF-1R with RNA pol II and DAPI (***p<0.001). D) After treatment with AZ12253801 and IGF-I as B), IGF-1Rβ was immunoprecipitated from chromatin and probed for IGF-1Rβ and histone H3.

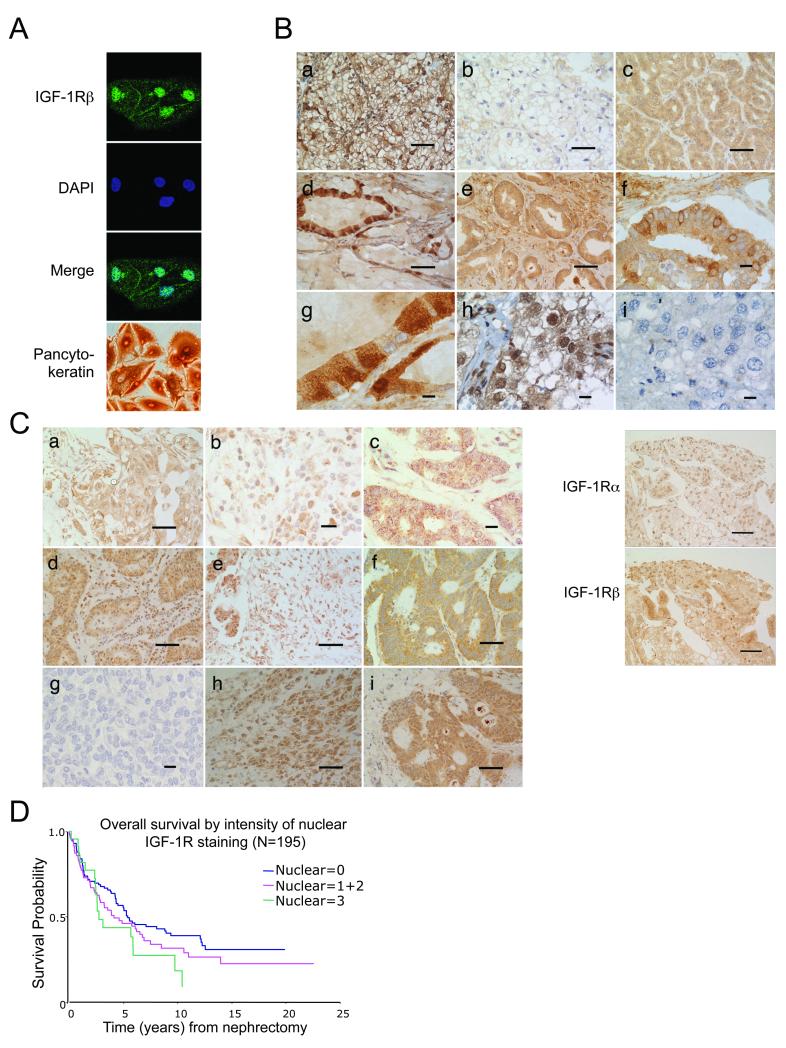

Finally, we investigated the clinical relevance of these findings. Nuclear IGF-1R was evident in primary RCC cultures (Figure 4A) and formalin-fixed RCC and prostate cancers, with marked heterogeneity between and within tumors (Figure 4B). Consistent with detection of both IGF-1R subunits in the nuclei of cultured tumor cells (Figure 2B, C), prostate cancers contained nuclear α- and β- immunoreactivity (Figure 4B, lower panel). Nuclear IGF-1R was detectable in additional tumor types including adenocarcinomas of the breast, lung and ovary, and in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; Figure 4C, Supplementary Table S1). The IGF-1R appeared almost exclusively nuclear in some breast and pancreatic cancers and malignant mixed Mullerian tumor, a rare, aggressive uterine malignancy (Figure 4C). Nuclear IGF-1R was also observed in benign epithelia of the esophagus, lung, breast, cervix, and prostate, and germ cells in the testis (Supplementary Table S1, Figure S7). This pattern suggests an association with proliferation, as reported for nuclear EGFR (5). Finally, we analyzed a series of clear cell RCCs, in which total IGF-1R expression is reported to have prognostic significance (24). Nuclear IGF-1R was detectable in 94/195 (48%) of clear cell RCCs. Multivariate analysis identified known prognostic factors (age, tumor grade, stage), and revealed that survival was shorter in patients whose tumors showed intense (p=0.005) and/or widespread (p=0.003) nuclear IGF-1R (Figure 4D, Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 4. Nuclear IGF-1R is detectable in human tumors, and is associated with poor prognosis in RCC.

A) Detection of nuclear IGF-1Rβ in primary RCC cells. Pancytokeratin positivity confirms epithelial origin. B) Upper: IGF-1Rβ immunohistochemistry in RCC (a-c, h, i) and prostate cancer (d-g) showing heterogeneous staining, with nuclear IGF-1R in a, d, g (high power view of d), h. Scale bar a-e 50μm; f-i 10μm. Lower: Prostate cancer stained for IGF-1R -α (24-31) or -β (3027 CST). Scale bar 50μm. C) Numerous human tumors contain nuclear IGF-1R. a-b: ductal carcinoma of breast, c: DCIS; d: non-small cell lung cancer; e: pancreatic adenocarcinoma; f: colon cancer; g: lymphoma; h: uterine MMMT; i: ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. Nuclear IGF-1Rβ detected in invasive cancers (a, b, d, e, h, i) and DCIS (c). Scale bar a, d-f, h, i 50μm; b, c, g 10μm. D) TMAs containing 195 clear cell RCCs stained for IGF-1Rβ and scored for nuclear IGF-1R intensity: 0 (nil), 1 (light), 2 (moderate), 3 (heavy). Nuclear IGF-1R intensity was associated with adverse prognosis (p=0.005).

In conclusion, these findings support the concept that nuclear IGF1R has biological significance. These data provide new insights into IGF biology, and may have implications for use of IGF-1R inhibitors in cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by MRC grant G0601061, the Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre programme, UCARE-Oxford (Urological Cancer Research and Education), and Cancer Research UK (grant A6293). We are grateful to Elizabeth Anderson, AstraZeneca, Alderley Park UK for AZ12253801, Ken Siddle, Cambridge UK for IGF-1Rα antibody 24-31, Renato Baserga, Philadelphia USA for R− and R+ cells, Neviana Kilbey and Cheng Han, Oxford Cancer Centre, for analysis of TMA data, and Ian Hickson and Hayley Whitaker for advice and comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chitnis MM, Yuen JS, Protheroe AS, Pollak M, Macaulay VM. The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6364–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams TE, Epa VC, Garrett TP, Ward CW. Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1050–93. doi: 10.1007/PL00000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vecchione A, Marchese A, Henry P, Rotin D, Morrione A. The Grb10/Nedd4 complex regulates ligand-induced ubiquitination and stability of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3363–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3363-3372.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romanelli RJ, LeBeau AP, Fulmer CG, Lazzarino DA, Hochberg A, Wood TL. Insulin-like growth factor type-I receptor internalization and recycling mediate the sustained phosphorylation of Akt. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22513–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin SY, Makino K, Xia W, et al. Nuclear localization of EGF receptor and its potential new role as a transcription factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:802–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao HJ, Carpenter G. Role of the Sec61 translocon in EGF receptor trafficking to the nucleus and gene expression. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007;18:1064–72. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sardi SP, Murtie J, Koirala S, Patten BA, Corfas G. Presenilin-dependent ErbB4 nuclear signaling regulates the timing of astrogenesis in the developing brain. Cell. 2006;127:185–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massie C, Mills IG. The developing role of receptors and adaptors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:403–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CW, Roy D. Up-regulation of nuclear IGF-I receptor by short term exposure of stilbene estrogen, diethylstilbestrol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellawell GO, Turner GD, Davies DR, Poulsom R, Brewster SF, Macaulay VM. Expression of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor is up-regulated in primary prostate cancer and commonly persists in metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2942–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuen JS, Cockman ME, Sullivan M, et al. The VHL tumor suppressor inhibits expression of the IGF1R and its loss induces IGF1R upregulation in human clear cell renal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:6499–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuen JS, Akkaya E, Wang Y, et al. Validation of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in renal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1448–59. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turney BW, Turner GDH, Brewster SF, Macaulay VM. Serial analysis of resected prostate cancer suggests up-regulation of type 1 IGF receptor with disease progression. BJU Int. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09556.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aleksic T, Feller SM. Gamma-secretase inhibition combined with platinum compounds enhances cell death in a large subset of colorectal cancer cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klinakis A, Szabolcs M, Chen G, Xuan S, Hibshoosh H, Efstratiadis A. Igf1r as a therapeutic target in a mouse model of basal-like breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2359–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810221106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McElroy B, Powell JC, McCarthy JV. The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor is a substrate for gamma-secretase-mediated intramembrane proteolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:1136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehat B, Andersson S, Girnita L, Larsson O. Identification of c-Cbl as a new ligase for insulin-like growth factor-I receptor with distinct roles from Mdm2 in receptor ubiquitination and endocytosis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5669–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo HW, Ali-Seyed M, Wu Y, Bartholomeusz G, Hsu SC, Hung MC. Nuclear-cytoplasmic transport of EGFR involves receptor endocytosis, importin beta1 and CRM1. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;98:1570–83. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu A, Chen J, Baserga R. Nuclear insulin receptor substrate-1 activates promoters of cell cycle progression genes. Oncogene. 2008;27:397–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehat B, Tofigh A, Lin Y, et al. SUMOylation mediates the nuclear translocation and signaling of the IGF-1 receptor. Sci Signal. 3:ra10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachdev D, Li SL, Hartell JS, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y, Miller JS, Yee D. A chimeric humanized single-chain antibody against the type I insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor renders breast cancer cells refractory to the mitogenic effects of IGF-I. Cancer Res. 2003;63:627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohr D, Frey S, Fischer T, Guttler T, Gorlich D. Characterisation of the passive permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:2541–53. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sexton T, Schober H, Fraser P, Gasser SM. Gene regulation through nuclear organization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1049–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker A, Cheville JC, Lohse C, Cerhan JR, Blute ML. Expression of insulin-like growth factor I receptor and survival in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;170:420–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000071474.70103.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.