Abstract

Background/Purpose

Given that emotional risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) tend to cluster within individuals, surprisingly little is known about how these negative emotions might influence one another over time. We examined the longitudinal associations among measures of depressive symptoms and hostility/anger in a cohort of 296 healthy, older adults.

Methods

Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Cook-Medley Hostility (Ho) scale, and Anger-In and Anger-Out subscales of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory at baseline and 6-year follow-up. We conducted a series of path analyses to evaluate the directionality of the depression-hostility/anger relationship.

Results

Baseline Ho scale was a predictor of 6-year increases in BDI-II (β = .15, p = .004), Anger-In (β = .14, p = .002) and Anger-Out (β = .11, p = .01). In contrast, baseline BDI-II, Anger-In, and Anger-Out did not predict change in any of the emotional variables. Additional path analytic models revealed that the pattern of relationships was not altered after controlling for demographic, biomedical, and behavioral covariates; anxiety symptoms; social support; and subjective sleep quality.

Conclusions

The present results suggest that the cognitive aspects of hostility/anger may precede and independently predict future increases in depressive symptoms but not vice versa. Our findings lead us to speculate that (a) hostility may exert part of its cardiotoxic influence by acting to precipitate and/or maintain symptoms of depression and that (b) the potency of depression interventions designed to improve cardiovascular outcomes might be enhanced by incorporating treatments addressing hostility.

Keywords: depression, hostility, anger, coronary artery disease, prospective study

It has long been hypothesized that emotional factors may play a role in the development and progression of coronary artery disease (CAD) (1). Supporting this notion, two meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies involving initially healthy individuals revealed that persons with elevated depressive symptoms have a 64% greater risk of CAD than do those with lower symptoms levels (2, 3). Greater depressive symptom severity also has been associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in samples of cardiac patients (4). Likewise, in another recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies (5), it was found that hostility/anger is associated with an increased risk of CAD among initially healthy persons (hazard ratio = 1.19) and with poorer prognosis among cardiac patients (hazard ratio = 1.24).

A substantial body of literature indicates that emotional risk factors for CAD tend to cluster within individuals (6), and recent evidence raises the possibility that negative emotions may act together to increase CAD risk (7, 8). Correlations between self-report measures of depressive symptoms and hostility/anger typically fall in the moderate (0.25–0.60) range (9–11), indicating that these construct share about 6% to 36% of their variance. It is worth noting that the positive association between depression and hostility/anger is robust, as it has been observed across hostility/anger measures that vary in terms of their conceptual definitions (e.g., cynicism, anger experience, and anger suppression/expression) and has been detected in a wide range of populations, including among men and women (12, 13), college students (14), older adults (7), and medical/psychiatric patients (15, 16). Although few studies have simultaneously examined multiple negative emotions as predictors of CAD-related processes and outcomes (6), results of two recent investigations indicate that depressive symptoms and hostility may interact and exert a synergistic effect on circulating levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein (7, 8), two inflammatory markers predictive of future cardiovascular events (17, 18).

Due to the dearth of prospective studies, however, little is known about how these emotional risk factors might affect one another over time – information that could help elucidate the ways in which depression and hostility/anger may jointly influence CAD risk. Smith’s psychosocial vulnerability model (19, 20) posits that hostility may contribute to CAD by virtue of its relationship with other psychosocial factors, such as reduced social support and increased interpersonal conflict, life stress, anxiety, and depression. The transactional model (19, 20) extends this theory by proposing the cynical cognitions and antagonistic behaviors of hostile individuals lead to the development of this toxic psychosocial environment. Similarly, in Kop’s biobehavioral model of CAD (21), it is asserted that chronic psychological factors (e.g., hostility) increase risk for CAD in part by promoting the onset of episodic psychological risk factors (e.g., depression), which themselves are linked to pathophysiological factors thought to play a role in CAD (e.g., autonomic nervous system dysfunction).

Results of the four previous studies that have examined the longitudinal relationship between depression and hostility/anger provide some support for the aforementioned theories. Specifically, Miller and colleagues (22) found that, among Mexican Americans, irritability predicted greater increases in the somatic symptoms of depression over 11 years. In a community sample, Reinherz et al. (23) detected a positive relationship between teacher-rated hostile behavior at age 6 and major depressive disorder in early adulthood. Likewise, Siegler and colleagues (24) observed that both hostility at college entry and change in hostility from college to midlife predicted future depressive symptom severity in a sample of predominantly white men. Recently, Heponiemi et al. (25) found that, among young adults, hostility predicted greater increases in depressive symptoms over a 5-year period. Thus, the available evidence, albeit limited, suggests that hostility/anger precedes and predicts depression. To our knowledge, the possibility that depression may be a predictor of later hostility/anger has not been empirically evaluated, although theoretical models have been put forward (26).

The objective of our study was to address four remaining questions in this literature. One, what is the directionality of the depression-hostility/anger relationship? Two, what role does anxiety play in this association? Self-report measures of anxiety are known to correlate strongly with depressive symptom measures (27) and moderately with hostility/anger measures (10, 28, 29). Furthermore, in one study in which anxiety was taken into account, the positive association between depressive symptoms and trait anger became nonsignificant after adjustment for trait anxiety (28). Three, does low social support and/or poor sleep quality partially explain the link between depression and hostility/anger? Low social support and poor sleep quality are among the leading candidate mediators of the relationship of interest, given that both factors have been found to be inversely associated with both depression and hostility/anger in cross-sectional studies (13, 30, 31) and to predict subsequent depression in prospective studies (25, 32). Four, is the magnitude of the relationship of interest greater for particular depressive symptom clusters? Previous research suggests that somatic symptoms of depression may be more strongly related to hostility/anger than are the cognitive and affective symptoms (22). To address these questions, we examined data collected as part of a 6-year prospective cohort study of healthy, community-dwelling, older adults. The knowledge gained from this and similar studies could have important implications for the field of cardiovascular behavioral medicine, as (a) it could be used to evaluate existing theories positing the ways in which depression and hostility/anger may work together to influence CAD risk and (b) it could inform the development of emotional interventions designed to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants were 296 men and women involved in the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project (PHHP), a 6-year prospective cohort study of healthy adults aged 50–70 years residing in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approved this study. Participants provided written informed consent and were paid $700 for attending the baseline and 6-year visits. Recruitment procedures and inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described in detail elsewhere (33). Individuals with a history of chronic disease generally were not eligible; however, persons with diabetes who were not taking insulin, those with a history of cancer but no treatment in the past two years, and those with mild or moderate rheumatoid arthritis were allowed to enroll. A total of 296 (64%) of the 464 enrolled adults attended the 6-year visits and were included in this report (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (N = 296)

| Demographic Factors | |

| Age (years) | 60.8 ± 4.7 |

| Sex, % female | 52.7 |

| Race-ethnicity, % nonwhite | 13.9 |

| Education level, % high school or less | 22.3 |

| Biomedical Factors | |

| History of diabetes, % | 1.0 |

| History of rheumatoid arthritis, % | 3.7 |

| History of cancer, % | 9.1 |

| Antidepressant use, % | 2.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7 ± 4.6 |

| Behavioral Factors | |

| Smoking status, % current smokers | 5.7 |

| Daily alcohol intake (g/day) | 6.4 ± 9.8 |

| Physical activity level (kilocalories/week) | 950.7 ± 803.7 |

Note. Values are means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

Measures and Procedure

We examined data collected during the PHHP baseline (1998–2000) and 6-year follow-up (2005–2006). Participants attended 11 baseline visits, which included a medical screen, seven visits for ambulatory monitoring training and questionnaire assessments on a computer, one visit for reactivity testing, and two visits for ultrasound assessments of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Approximately six years later (M = 6.3, SD = 0.2), participants returned for six follow-up visits, during which a medical update, questionnaire assessments, ambulatory monitoring training, ultrasound assessments, and autonomic testing were completed.

Depressive Symptoms

Participants were administered the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (34) at the third baseline and follow-up visits (see Table 2). The BDI-II is a widely used, 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptom severity that has been shown to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity (34, 35). Due to an oversight while constructing the computerized version, participants were asked to rate the severity of their depressive symptoms over the past week (the time frame for the original BDI) instead of the past two weeks (the usual time frame for the BDI-II). We also computed two BDI-II subscale scores – a cognitive-affective score (sum of items 1–3, 5–9, 13, and 14) and a somatic-vegetative score (sum of items 4, 10–12, and 15–21) (35). The BDI-II total scores, cognitive-affective scores, and somatic-vegetative scores were log (Xi+1) transformed to decrease positive skew.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for and Correlations among Measures of Depressive Symptoms and Hostility/Anger

| M ± SD | Cronbach’s α | BDI-II | Ho Scale | Anger-In | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||

| BDI-II | 3.8 ± 3.9 | .78 | --- | ||

| Ho Scale | 8.1 ± 4.0 | .74 | .20* | --- | |

| Anger-In | 15.0 ± 3.7 | .74 | .22* | .18* | --- |

| Anger Out | 13.1 ± 2.8 | .70 | .08 | .15* | −.03 |

| 6-Year Follow-up | |||||

| BDI-II | 5.1 ± 5.1 | .84 | --- | ||

| Ho Scale | 9.8 ± 4.4 | .78 | .24* | --- | |

| Anger-In | 14.0 ± 3.4 | .71 | .32* | .27* | --- |

| Anger-Out | 12.8 ± 3.2 | .79 | .13* | .24* | .13* |

Note. N ranges from 288–295 due to missing data. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II. Ho Scale = Cook-Medley Hostility Scale. Anger-In = Anger-In subscale of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. Anger-Out = Anger-Out subscale of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory.

p < .05.

Hostility/anger

Hostility/anger is a broad personality dimension consisting of cognitive (cynicism and mistrust), affective (anger), and behavioral (verbal/physical aggression) aspects (36). In this study, participants completed the Cook-Medley Hostility (Ho) scale (37) at fourth baseline and follow-up visits and the Anger-In and Anger-Out subscales of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) (29) at the ninth baseline and fourth follow-up visits (see Table 2). The Ho scale is a 50-item, true-false instrument derived from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory that has adequate internal consistency and moderate to high test-retest reliability and construct validity (11, 38, 39). One item was accidentally omitted from the baseline Ho scale; the value for this item was imputed by taking the mean of the other items for each participant. We computed the total score for the 27-item version of the Ho scale (40) instead of the original 50-item version at both baseline and follow-up because only the 27-item version was administered during the 6-year visits. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the 27-item version may be a stronger predictor of health outcomes than the full Ho scale (40). The Anger-In and Anger-Out subscales of the STAXI, each of which consist of eight items rated on a 1–4 scale, were designed to measure how often one suppresses angry feelings and how often one expresses anger toward others or objects, respectively. The STAXI has been found to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, construct validity (29, 41).

A factor analysis conducted on multiple measures of hostility/anger revealed that a three-factor solution provided the best fit to the data; the Ho scale and Anger-In loaded on the cynical cognition factor, and Anger-Out loaded on the angry affect and behavioral aggression factors (42). Another large factor analysis yielded similar results, except that Anger-In loaded on the neuroticism factor instead of the alienation-suspicion factor, which included cynicism (43). In light of these results, we consider the Ho scale to be an indicator of the cognitive aspects of hostility/anger, Anger-In to be a mixed indicator of the cognitive and affective aspects, and Anger-Out to be a mixed indicator of the affective and behavioral aspects.

Other Psychosocial Factors

To assess anxiety symptoms (past week), the perceived availability of social support (current), and subjective sleep quality (past month), participants were administered the 21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (44), 40-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) (45), and Items #2 (sleep latency) and #4 (sleep duration) of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (46) at baseline. The BAI, ISEL, and PSQI each have demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties, including at least adequate internal consistency, test-retest-reliability, and construct validity (45–47). Mean scores on the BAI and ISEL were 5.0 (SD = 4.7) and 97.4 (SD = 14.2), respectively. The average sleep latency was 12.7 minutes (SD = 13.4), and the average sleep duration was 6.9 hours (SD = 1.1). The BAI total score and PSQI Item #2 were both log (Xi+1) transformed to minimize positive skew.

Biomedical and Behavioral Factors

During the baseline visits, participants completed questionnaires and interviews to assess the following factors: age (years), sex (0 = male, 1 = female), race-ethnicity (1 = white, 2 = black, 3 = Asian, 4 = Hispanic, 5 = other), education level (0 = high school or less, 1 = more than high school), history of various medical conditions (including diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer), antidepressant use (0 = no, 1 = yes), smoking status (0 = nonsmoker, 1 = smoker), daily alcohol intake, and physical activity level (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Because only six participants selected the Asian, Hispanic, or other categories, race-ethnicity was recoded into a binary variable (0 = white, 1 = non-white). Daily alcohol intake (g/day) was calculated using a quantity-frequency method (48). Physical activity level was computed by first converting the number of blocks walked and stairs climbed per day reported on Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire (49) to kilocalories per week and then summing these values. At the baseline medical screen, anthropometric measurements were also obtained, and body-mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2. To reduce positive skew, daily alcohol intake was log (Xi+1) transformed and physical activity level was square root transformed.

Statistical Analysis

We performed preliminary analyses to evaluate the internal consistency of the emotional measures (Cronbach’s alphas), to examine the cross-sectional relationships among these measures (bivariate correlations), and to characterize the change over time observed in these measures (paired-samples t tests). Then, we conducted a series of measured variable path analyses using LISREL 8.8 (50) to address the key questions of this study. Path analysis has several advantages over traditional regression analysis, such as the ability to predict multiple outcomes and handle missing data, both of which result in more accurate parameter estimates. We conducted measured variable path analyses because our sample was not of adequate size to perform latent variable path analyses (i.e., the cases/parameters ratio would have fallen below accepted standards) (51). To assess model fit, we examined two goodness-of-fit statistics – the model chi-square and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (51). The model chi-square is an index of absolute fit between the hypothesized model and the observed pattern of associations among measured variables; a nonsignificant model chi-square statistic is indicative of acceptable model fit. The RMSEA is a parsimony-adjusted index, as it corrects the absolute fit estimate for the complexity of the hypothesized model. RMSEA is indicative of close fit when it is < .05, reasonable fit when it is between .05–.08, and poor fit when it is > .10 (52). Parameters were estimated by full information maximum likelihood, a method that uses all of the observed data and is preferable to traditional missing data approaches (53).

To evaluate the directionality of the depression-hostility/anger relationship, two path analytic models were constructed. The first model included BDI-II, Ho scale, Anger-In, and Anger-Out measured at baseline and follow-up. Of these eight variables, those assessed at the same time point were allowed to correlate with one another. We also adjusted follow-up BDI-II, Ho scale, Anger-In, and Anger-Out for their corresponding baseline score by including structural paths between these variables. Thus, the follow-up variables represent residualized change scores (e.g., 6-year change in BDI-II). In addition, we connected each baseline variable to each of the remaining follow-up variables with a structural path. The two exceptions were that structural paths from baseline Anger-In to follow-up Anger-Out and vice versa were omitted because (a) including them would have resulted in a saturated model (precluding an evaluation of model fit) and (b) these paths were not relevant to the key questions of this study. Of note, neither of these paths was significant when added to this model (both ps > .21).

In order to ascertain whether any of the observed relationships was due to potential confounders, we constructed a second model that included demographic (age, sex, race-ethnicity, and education level), biomedical (history of diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer; antidepressant use; and BMI), and behavioral (smoking status, daily alcohol intake, and physical activity level) covariates measured at baseline. Each of these control variables was allowed to correlate with each of the baseline variables, including the other covariates. Because the selected covariates were plausible predictors of longitudinal changes in depressive symptom severity and hostility/anger, each control variable was linked to each follow-up variable with a structural path.

To determine the influence of anxiety on any relations observed among the measures of depressive symptoms and hostility/anger, baseline BAI was added to the second model. Like the other control variables, it was allowed to correlate with the other baseline variables and was connected to each follow-up variable with a structural path. In addition, to explore whether low social support and poor sleep quality might be mediators of any observed associations, two sets of baseline variables (Set 1 = ISEL; Set 2 = PSQI Items #2 and #4) were added, one set at a time, to the second model. These variables, which were allowed to correlate with the other baseline variables, were linked to each follow-up variable with a structural path. Finally, to examine whether the magnitude of any observed relationships was greater for particular clusters of depressive symptoms, we repeated the second model after substituting BDI-II cognitive-affective and somatic-vegetative scores at baseline and follow-up for the corresponding BDI-II total scores. A chi-square difference test was conducted to determine whether the freely estimated models (coefficients for the BDI-II subscales were estimated separately) yielded better data-model fit than the constrained models (coefficients for the BDI-II subscales were set to be equal).

Results

As can be seen in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable and similar in magnitude for all of the emotional measures, demonstrating that these measures had at least adequate internal consistency. Bivariate correlations indicated that the cross-sectional relationships between BDI-II and the Ho Scale and Anger-In were moderate in size at both baseline and follow-up (r = .20–.32). In contrast, the magnitude of associations between BDI-II and Anger-Out fell in the small range (r = .08–.13). Paired-samples t tests revealed that, at the group level, scores on the BDI-II [t(288) = −5.06, p < .01] and Ho scale [t(286) = 8.43, p < .01] increased during the follow-up period, whereas scores on Anger-In [t(282) = −5.89, p < .01] and Anger-Out [t(282) = 1.99, p = .047] decreased. As is evidenced by the relatively large variability in the arithmetic difference scores (SD = 2.4–4.5), there were considerable individual differences in change over time in each emotional factor.

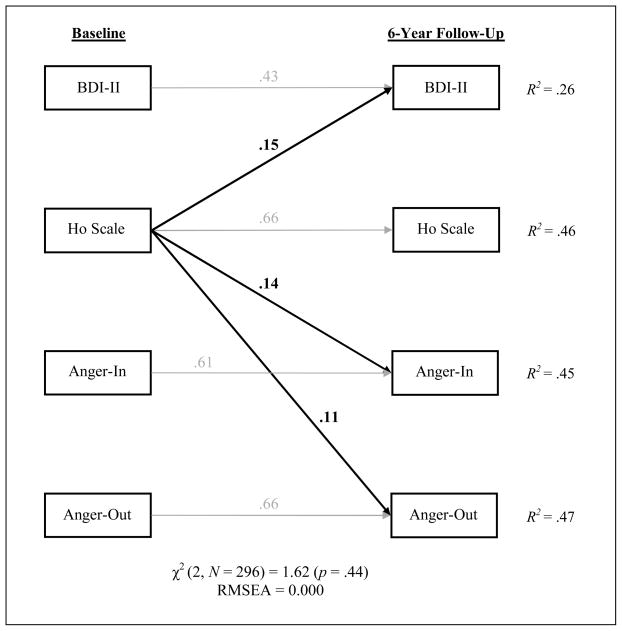

We constructed two path analytic models to evaluate the directionality of the depression-hostility/anger relationship. The first model included only the emotional variables of interest and showed close fit to the data, χ2 (2, N = 296) = 1.62 (p = .44), RMSEA = 0.000. As can be seen in Figure 1, baseline BDI-II (β = .43, p < .001), Ho scale (β = .66, p < .001), Anger-In (β = .61, p < .001), and Anger-Out (β = .66, p < .001) were each strongly related to their corresponding follow-up scores. Baseline BDI-II was not a predictor of 6-year change in Ho scale, Anger-In, or Anger-Out (all ps > .13); however, baseline Ho scale did predict BDI change (β = .15, p = .004) and explained 2% of the variance beyond that accounted for baseline BDI-II and the other emotional variables. Baseline Ho scale also predicted change in Anger-In (β = .14, p = .002) and Anger-Out (β = .11, p = .01), explaining an additional 1% and 2% of the variance, respectively. Anger-In and Anger-Out were not predictors of change in BDI-II or Ho scale (all ps > .25).

Figure 1.

Results of the path analysis examining the longitudinal associations among measures of depressive symptoms and hostility/anger. Values associated with unidirectional arrows (i.e., structural paths) are standardized regression coefficients. Only the significant structural paths are shown in the figure; correlations and nonsignificant structural paths were omitted. N = 296.

In the second model, we included baseline demographic, biomedical, and behavioral covariates (see Statistical Analysis section for variable list). This model also fit the data well, χ2 (2, N = 296) = 1.49 (p = .47), RMSEA = 0.000. Of the covariates, age (β = .12, p = .03), sex (β = .14, p = .01), and smoking status (β = .14, p = .01) predicted BDI-II change; none predicted Ho scale change; and race-ethnicity predicted Anger-In change (β = −.09, p = .05) and Anger-Out change (β = −.12, p = .01). Importantly, including these covariates did not change the nature of relationships observed in the first model. Baseline Ho scale remained a predictor of 6-year change in BDI-II (β = .15, p = .007), Anger-In (β = .15, p = .002), and Anger-Out (β = .12, p = .01), whereas baseline BDI-II, Anger-In, and Anger-Out did not predict change in any of the emotional variables (all ps > .08).

To determine the effect of anxiety on the association we detected between baseline Ho scale and BDI-II change, we added baseline BAI to the second model. Not surprisingly, baseline BAI was a predictor of 6-year change in BDI-II (β = .17 p = .004); however, it was not a predictor of Ho scale, Anger-In, or Anger-Out change (all ps > .35). Of greatest relevance, baseline Ho scale remained a predictor of BDI-II change (β = .13, p = .02). Next, we explored whether low social support or poor sleep quality might mediate the observed relationship between baseline Ho scale and BDI-II change. We first added baseline ISEL to the second model, which indicated that ISEL did not predict change in any of the hostility/anger measures (all ps > .25) but did predict BDI-II change (β = −.12, p = .04). Adjusting for ISEL, however, did not weaken the association of baseline Ho scale with BDI-II change (β = .14, p = .01). We then added baseline PSQI Items #2 (sleep latency) and #4 (sleep duration) to the second model. Although sleep duration was not related to change in any emotional variable (all ps > .21) and sleep latency was not associated with change in any hostility/anger measure (all ps > .31), sleep latency was a predictor of BDI-II change (β = .12, p = .02). Again, the strength of the association between baseline Ho scale and BDI-II change (β = .15, p = .01) was not altered. Finally, the analysis in which the BDI-II subscale scores were substituted for the total score revealed that baseline Ho scale predicted change in the somatic-vegetative subscale (β = .16, p = .005) but not the cognitive-affective subscale (β = .10, p = .09). A chi-square difference test, however, demonstrated that these coefficients were not significantly different from each other, Δχ2 (1, N = 296) = 1.38 (p = .24).

Discussion

Although depression and hostility/anger are emerging risk factors for CAD that tend to cluster within individuals, it is not yet known how these negative emotional factors might influence one another over time. In this prospective cohort study, we observed that a measure of the cognitive aspects of hostility/anger (Ho scale), but not mixed measures of the cognitive/affective (Anger-In) or the affective/behavioral (Anger-Out) aspects, predicted greater increases in depressive symptoms (BDI-II) over six years. We also found that the BDI-II did not predict 6-year changes in any of the hostility/anger measures and that the Ho scale predicted greater 6-year increases in Anger-In and Anger-Out. The detected cynicism-depression relationship persisted in the presence of demographic, biomedical, and behavioral factors as well as anxiety symptoms, perceived social support, and subjective sleep latency and duration, indicating that these factors are not likely confounders or mediators. In addition, we report suggestive evidence that the observed relationship may primarily reflect an association between cynicism and the somatic-vegetative symptoms of depression. This result, however, should be interpreted cautiously, as the relationships between the Ho scale and the two BDI-II subscales were similar in magnitude. Taken together, our findings indicate that the cognitive aspects of hostility/anger precede and independently predict future increases in depressive symptoms, which suggests that cynicism may be a cognitive risk factor (contributing to the index episode) and/or maintaining factor (contributing to subsequent episodes) for depression. Moreover, our results support the hostility-to-depression paths included in Smith’s psychosocial vulnerability and transactional models (19, 20) and Kop’s biobehavioral model of CAD (21) – theories which assert that depression is one pathway through which hostility may increase cardiovascular risk.

The present findings are broadly consistent with the results of the four previous studies examining the relationship between hostility/anger and later depression. In those investigations, persons with elevated hostility/anger levels exhibited greater increases in depressive symptoms over time (22, 25) or were at increased risk for depression later in life (23, 24). Similar to our study, both Heponiemi et al. (25) and Siegler et al. (24) detected an association between a measure of cynicism and future depressive symptoms. Also paralleling our findings, the results of Miller and colleagues (22) suggest that hostility may predict future increases in the somatic symptoms but not the other depressive symptom clusters. Because Reinherz et al. (23) utilized a measure that primarily assesses aggression, at a finer level of analysis, their findings are at odds with the lack of association between Anger-Out and BDI-II change that we report. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate depressive symptom severity as a predictor of longitudinal changes in hostility/anger; thus, there are no results to which we can compare ours. Although somewhat surprising given the length of follow-up, our finding that the Ho scale predicted future Anger-In and Anger-Out is in line with Smith’s transactional model (19, 20), which posits that hostile cognitions precede and contribute to episodes of anger and aggression.

Several psychological and physiological factors are candidate mediators of the observed prospective relationship. It has been suggested that elevated anxiety (28) and low social support (9) may be among the mechanisms underlying the connection between hostility/anger and later depression; however, evidence from this study and a similar investigation (25) does not support this notion. We also did not observe any evidence of mediation by two indicators of subjective sleep quality. Instead, we found that elevated anxiety symptoms, low perceived social support, and prolonged sleep latency were each independent predictors of 6-year increases in depressive symptoms. It is possible, however, that psychological factors that we did not examine could be operating as mediators. For instance, hostile persons may chronically experience a high degree of interpersonal stress (9), perhaps due to their negative attitudes about others (11, 54, 55) and their tendency to employ poor coping strategies (55, 56). Increased life stress and ineffectual ways of coping, together or individually, could lead to the development or exacerbation of depression (57, 58). It is worth noting, however, that life stress could also be a confounder of the detected cynicism-depression relationship. Another possibility is that the effect of hostility/anger on depressive symptoms may be mediated by dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is believed to play an etiologic role in the development of depression (59). Even though few studies have evaluated HPA axis function among hostile individuals, the available evidence suggests that hostility is associated with HPA axis hyperactivity (60–62).

In addition to these causal models, there are alternative explanations that we cannot rule out. First, the cynicism-depression relationship we report may reflect a common physiological dysfunction that exerts its influence on hostility/anger earlier than on depressive symptoms. One such factor that has been linked to hostility (63) and depression (64) is reduced central serotonergic function. Second, shared genetic influences could also account for the observed relationship, as Raynor and colleagues (13) found that genetic effects explained 61% of the covariation between Ho scale and BDI-II scores. Third, baseline BDI-II (21%) accounted for considerably less variance in its follow-up score than did the Ho scale (43%), Anger-In (42%), and Anger-Out (45%). Therefore, we may not have detected a relationship between depressive symptoms and later hostility/anger because of the smaller amount of residual variance in the 6-year hostility/anger scores left to be explained.

The current study has some limitations that are worthy of comment. One, in contrast to the cognitive aspects, we did not administer “pure” measures of the affective and behavioral aspects of hostility/anger. Consequently, we are not able to draw strong inferences regarding the nature of the longitudinal relationships (or lack thereof) between angry affect or behavioral aggression and depressive symptoms. For instance, we can only speculate that we may have failed to detect an association between Anger-In and 6-year change in depressive symptoms because Anger-In is a mixed indicator of cynicism and angry affect, and the affective aspects of hostility/anger may not be predictive of later depressive symptoms. Two, variability in BDI-II scores was somewhat limited, possibly because (a) our sample consisted of volunteers from the community and (b) the participants were instructed to rate the severity of their depressive symptoms over the past week instead of the past two weeks, which may have yielded lower scores (35). This restricted variability may have resulted in an underestimation of the effect sizes of the relationships involving depressive symptoms. Three, because our participants were older, healthy, and mostly non-Hispanic white, our results might not generalize to younger populations, older populations with a high prevalence of chronic disease, or other racial/ethic groups.

Our primary finding – that the cognitive aspects of hostility/anger predict future increases in depressive symptoms – could have important implications for the field of cardiovascular behavioral medicine. First, we confirmed the hostility-to-depression paths of the theories put forth by Smith (19, 20) and Kop (21). These models imply that depression and hostility may act together in a serial fashion to influence CAD risk (i.e., hostility may promotes depression, which in turn may bring about pathophysiological changes that play a role in the pathogenesis of CAD). However, despite the apparent temporal precedence of hostility over depression, the possibility that these emotional factors may have additive or synergistic effects on CAD-related processes and outcomes also remains plausible. Second, our findings could inform the development of interventions designed to reduce CAD risk or slow its progression by targeting emotional factors. Because we found that cynicism may be a cognitive risk and/or maintaining factor for depression, our results lead us to speculate that the potency of depression interventions designed to improve cardiovascular outcomes might be enhanced by incorporating psychosocial (65) or pharmacological (66) treatments addressing hostility. In other words, to bring about lasting change in one emotional risk factor for CAD (depression), it may be necessary to concurrently address another one (hostility).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL56346 awarded to Dr. Kamarck and HL040962 awarded to Dr. Stephen Manuck as well as Pittsburgh Mind-Body Center Grants HL076852 and HL076858. Some of these data were presented at the 67th annual meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society, March, 2009, Chicago, IL. We thank the entire project staff of the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Booth-Kewley S, Friedman HS. Psychological predictors of heart disease: A quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:343–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. a review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wulsin LR, Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:201–210. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058371.50240.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, et al. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:814–822. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:936–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:260–300. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart JC, Janicki-Deverts D, Muldoon MF, Kamarck TW. Depressive symptoms moderate the influence of hostility on serum interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:197–204. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181642a0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez EC. Joint effect of hostility and severity of depressive symptoms on plasma interleukin-6 concentration. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:523–527. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000062530.94551.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felsten G. Hostility, stress, and symptoms of depression. Personality & Individual Differences. 1996;21:461–467. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman HS, Booth-Kewley S. Personality, type A behavior, and coronary heart disease: the role of emotional expression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:783–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TW, Frohm KD. What’s so unhealthy about hostility? Construct validity and psychosocial correlates of the Cook and Medley Ho scale. Health Psychol. 1985;4:503–520. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummett BH, Barefoot JC, Feaganes JR, et al. Hostility in marital dyads: Associations with depressive symptoms. J Behav Med. 2000;23:95–105. doi: 10.1023/a:1005424405056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raynor DA, Pogue-Geile MF, Kamarck TW, McCaffery JM, Manuck SB. Covariation of psychosocial characteristics associated with cardiovascular disease: Genetic and environmental influences. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:191–203. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridewell WB, Chang EC. Distinguishing between anxiety, depression, and hostility: Relations to anger-in, anger-out, and anger control. Personality & Individual Differences. 1997;22:587–590. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh KB, Kim CH, Park JK. Predominance of anger in depressive disorders compared with anxiety disorders and somatoform disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:486–492. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschannen TA, Duckro PN, Margolis RB, Tomazic TJ. The relationship of anger, depression, and perceived disability among headache patients. Headache. 1992;32:501–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1992.hed3210501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–1772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller TQ, Smith TW, Turner CW, Guijarro ML, Hallet AJ. Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:322–348. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith TW. Hostility and health: Current status of a psychosomatic hypothesis. Health Psychol. 1992;11:139–150. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kop WJ. Chronic and acute psychological risk factors for clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:476–487. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller TQ, Markides KS, Chiriboga DA, Ray LA. A test of the psychosocial vulnerability and health behavior models of hostility: Results from an 11-year follow-up study of Mexican Americans. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:572–581. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Carmola Hauf AM, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: Risks and impairments. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:500–510. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegler IC, Costa PT, Brummett BH, et al. Patterns of change in hostility from college to midlife in the UNC Alumni Heart Study predict high-risk status. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:738–745. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088583.25140.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, et al. The longitudinal effects of social support and hostility on depressive tendencies. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiGiuseppe R, Tafrate RC. Understanding anger disorders. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 418. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mook J, van der Ploeg H, Kleijn W. Anxiety, anger and depression: Relationships at the trait level. Anxiety Research. 1990;3:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spielberger CD. State-trait anger expression inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin C, Kim J, Yi H, et al. Relationship between trait-anger and sleep disturbances in middle-aged men and women. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1254–1268. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord. 2003;76:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamarck TW, Muldoon MF, Shiffman SS, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Experiences of demand and control during daily life are predictors of carotid atherosclerotic progression among healthy men. Health Psychol. 2007;26:324–332. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barefoot JC, Lipkus IM. The assessment of anger and hostility. In: Siegman AW, Smith TW, editors. Anger, hostility, and the heart. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1954;38:414–418. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barefoot JC, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB., Jr Hostility, CHD incidence, and total mortality: a 25-year follow-up study of 255 physicians. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:59–63. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shekelle RB, Gale M, Ostfeld AM, Paul O. Hostility, risk of coronary heart disease, and mortality. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:109–114. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB., Jr The Cook-Medley hostility scale: item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bishop GD, Quah S-H. Reliability and validity of measures of anger/hostility in Singapore: Cook & Medley Ho Scale, STAXI and Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;24:867–878. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin R, Watson D, Wan CK. A three-factor model of trait anger: Dimensions of affect, behavior, and cognition. J Pers. 2000;68:869–897. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Reise SP. Personality dimensions and measures potentially relevant to health: A focus on hostility. Ann Behav Med. 1995;17:245–253. doi: 10.1007/BF02903919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck TW, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research and applications. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garg R, Wagener DK, Madans JH. Alcohol consumption and risk of ischemic heart disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1993;153:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL (Version 8.8) Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Enders CK. The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:713. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott WD, Ingram RE, Shadel WG. Hostile and sad moods in dysphoria: Evidence for cognitive specificity in attributions. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2003;22:233–252. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vandervoort DJ. Hostility and health: Mediating effects of belief systems and coping styles. Current Psychology. 2006;25:50–66. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mao WC, Bardwell WA, Major JM, et al. Coping strategies, hostility, and depressive symptoms: a path model. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;10:331–342. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1004_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, Schutte KK. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:658–666. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arborelius L, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol. 1999;160:1–12. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keltikangas-Jaervinen L, Raeikkoenen K, Adlercreutz H. Response of the pituitary-adrenal axis in terms of Type A behaviour, hostility and vital exhaustion in healthy middle-aged men. Psychology & Health. 1997;12:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pope MK, Smith TW. Cortisol excretion in high and low cynically hostile men. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:386–392. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Jr, Zimmermann EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manuck SB, Flory JD, McCaffery JM, et al. Aggression, impulsivity, and central nervous system serotonergic responsivity in a nonpatient sample. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:287–299. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mann JJ, McBride PA, Malone KM, DeMeo M, Keilp J. Blunted serotonergic responsivity in depressed inpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gidron Y, Davidson K, Bata I. The short-term effects of a hostility-reduction intervention on male coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18:416–420. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kamarck TW, Haskett RF, Muldoon M, et al. Citalopram intervention for hostility: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:174–188. doi: 10.1037/a0014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]