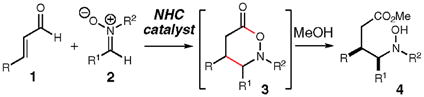

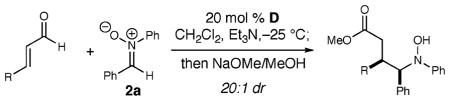

Harnessing unconventional reactivity for new bond-forming processes provides unusual avenues for the synthesis of target molecules. Non-traditional cycloadditions outside the venerable [4 + 2] and [3 + 2] processes also facilitate access to desired compounds in a highly convergent manner by combining at least two simple starting materials.1 A relatively unexplored class of powerful transformations utilizes unusual reactivity patterns, such as homoenolates, in the context of non-traditional, formal cycloadditions. In this communication, we report the highly diastereo- and enantioselective combination of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (1) with nitrones (2) catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbenes to afford γ-amino esters, such as 4, upon the addition of an alcohol (eq 1). A unique aspect of this process is the rare six-membered heterocycle that is generated as the initial product of the reaction (3).

|

(1) |

The successful addition of homoenolate species to nitrones would be a significant transformation since the products are potentially γ-amino acids. These molecules are used clinically as modulators of neurotransmission,2 and the related γ-lactam structure is a key constituent of many natural products (e.g., lactacystin)3 as well as pharmaceutical agents. To our knowledge, there are no reports of homoenolate additions to nitrones under either catalytic or stoichiometric conditions.4

Our efforts5 and those of others6 investigating the area of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis have recently yielded innovative methods to access unique homoenolate reactivity. In these processes, an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde possesses nucleophilic character at the β-carbon which upon addition to an electrophile yields an activated ester. In light of our experience with these atypical nucleophiles, we envisioned that nitrones should be productive in a formal [3 + 3] reaction since they are useful reactants in a variety of cycloaddition reactions.7

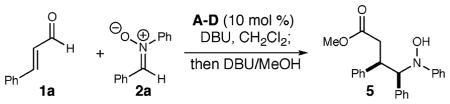

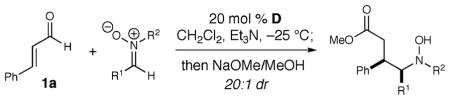

We initiated these investigations by combining cinnamaldehyde (1a) and diphenyl nitrone (2a) while surveying different triazolium salts and reaction conditions (Table 1). While thiazolium and imidazolium salts did not produce desired products, the use of achiral triazolium salt A at 10 mol % afforded complete consumption of the nitrone (entry 1). Initially, a challenging aspect of this processes was the characterization and manipulation of the first product formed in the reaction (i.e., 3). This unusual heterocycle was unstable to chromatography, but by adding methanol and DBU to the reaction after consumption of the nitrone, the γ-hydroxyl amino ester (5) could be isolated in 75% yield. With this protocol, a screen of chiral triazolium salts revealed that azolium D, originally developed in our laboratory,5c generated 5 with high levels of stereoselectivity (8:1 dr, 87% ee) but only moderate yield (entry 4). Lowering the temperature provided increased selectivity (20:1 dr, 93% ee) and yield of 5 with 20 mol % of D necessary for consumption of 1a (entry 6). Last, changing the MeOH/DBU addition at the end of the reaction to NaOMe provided the methyl ester products in consistently higher yield.8

Table 1.

Optimization of Conditions

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | azolium salt | temp (°C) | yielda (%) | drb | eec (%) |

| 1 | A | 0 | 75d | 4:1 | |

| 2 | B | 0 | 46d | 8:1 | −65 |

| 3 | C | 0 | 52d | 8:1 | −33 |

| 4 | D | 0 | 51d | 8:1 | 87 |

| 5 | D | −25 | 49d | 20:1 | 93 |

| 6 | De | −25 | 70f | 20:1 | 93 |

Isolated yields.

Diastereomeric ratio determined by 500 MHz NMR spectroscopy.

Enantiomeric excess determined by HPLC Chiracel AD-H.

2:1 ratio of 1a to 2a.

20 mol % of D, Et3N used instead of DBU.

2:1 ratio of 2a to 1a, NaOMe/MeOH used in place of DBU/MeOH.

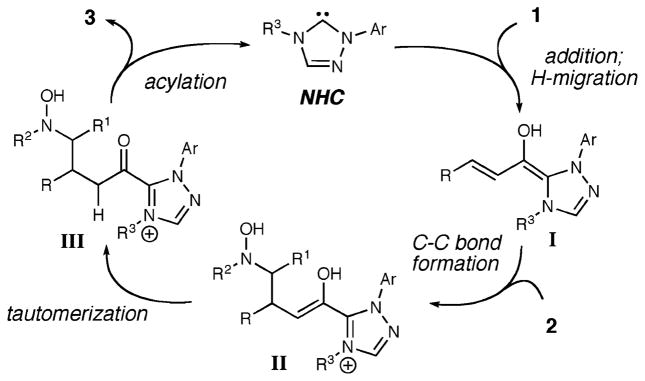

Our current model for this reaction (Scheme 1) involves the addition of the homoenolate equivalent (I, formed in situ from the combination of the NHC and unsaturated aldehyde) to the nitrone (2). After this stereochemical-determining step, catalyst turnover is promoted by an intramolecular acylation after the tautomerization of enol II to acyl azolium III. As in a majority of recent carbene-catalyzed processes, the success of this pathway relies on (a) a nonproductive interaction between the secondary electrophile in the reaction (nitrone) and the in situ generated catalyst, and (b) a productive interaction between the catalyst and primary electrophile (α,β-unsaturated aldehyde).

Scheme 1.

Reaction Pathway

We first examined the scope of this reaction with regard to nitrone substituents (Table 2). The reaction accommodates both electron-withdrawing and -donating aromatic substitution on the carbon (R1) with high levels of dr and %ee (entries 1–5).9 Nitrones derived from saturated aldehydes were not suitable substrates. An electron-withdrawing aromatic ring (4-chlorophenyl) on the nitrogen of the nitrone provided the methyl ester in moderate yield with high selectivity (entry 7). Electron-donating groups on the nitrogen, such as 4-methoxyphenyl or 4-methylphenyl, resulted in no product formation (not shown).

Table 2.

Nitrone Reaction Scope

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | yielda (%) | eeb (%) |

| 1 | Ph | Ph | 70 (5) | 93 |

| 2 | 4-Me–C6H4 | Ph | 71 (6) | 90 |

| 3 | 4-Br–C6H4 | Ph | 68 (7) | 84 |

| 4 | 4-MeO-C6H4 | Ph | 62 (8) | 90 |

| 5 | 2-naphthyl | Ph | 69 (9) | 81 |

| 6 | cyclohexyl | Ph | 0 | |

| 7 | Ph | 4Cl-Ph | 80 (10) | 93 |

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric excess determined by HPLC Chiracel OD-H or AD-H. Diastereomeric ratio determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (500 MHz).

We then varied the aldehyde component of this new reaction (Table 3). Electron-withdrawing and -donating groups on the aromatic ring of the aldehyde are tolerated well (entries 1 and 2). Importantly, α,β-unsaturated aldehydes with alkyl groups in the β-position afford the desired γ-hydroxy amino esters with high selectivity and good yields (entries 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Aldehyde Reaction Scope

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | yielda (%) | eeb (%) |

| 1 | 4-Cl–C6H4 | 78 (11) | 90 |

| 2 | 4-MeO–C6H4 | 72 (12) | 89 |

| 3 | 2-naphthyl | 73 (13) | 94 |

| 4 | Mec | 73 (14) | 94 |

| 5 | C3H7c | 64 (15) | 92 |

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric excess determined by HPLC Chiracel OD-H or AD-H.

DBU used in place of Et3N.

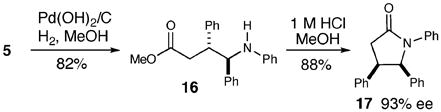

With an efficient pathway to γ-hydroxy amino methyl esters, we envisaged that cleavage of the N–O bond would facilitate clean access to γ-amino esters (eq 2). The N–O bond is easily cleaved under a hydrogen atmosphere in the presence of Pd(OH)2, and subsequent exposure of the amino ester to aqueous HCl in methanol provides the corresponding lactam 17 in 88% yield and 93% ee.10

|

(2) |

In summary, we have developed the first highly diastereo- and enantioselective homoenolate addition to nitrones catalyzed by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. This formal [3 + 3] addition delivers γ-amino ester derivatives and is the first general and highly selective strategy for the addition of homoenolate nucleophiles to nitrones. Electron-rich and electron-poor aryl groups are suitable substituents on the carbon of the nitrone, and alkyl and aryl groups are tolerated on the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. Scission of the N–O bond under mild conditions results in the formation of γ-amino esters that quickly close in the presence of acid to form γ-lactams in good yields. N-Heterocyclic carbene catalysis is a powerful approach that provides new directions for synthesis through innovative bond construction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was generously provided by NIGMS (RO1 GM73072), Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, 3M, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Funding for the NU Analytical Services Laboratory has been furnished in part by the NSF (CHE-9871268). We thank Dr. William J. Morris for helpful discussions. K.A.S. is a Fellow of the Sloan Foundation. T.E.R. is a recipient of a 2007–2008 ACS Division of Organic Chemistry fellowship sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For selected reviews of cycloadditions beyond [4 + 2] and [3 + 2] manifolds, see: Rigby JH. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1991. p. 617.Hosomi A. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1991. p. 593.Brummond KM, Kent JL. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:3263–3283.Murakami M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:718–720. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390200.Wender PA, Gamber GG, Williams TJ. In: Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2005. pp. 263–300.

- 2.(a) Bryans JS, Wustrow DJ. Med Res Rev. 1999;19:149–177. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199903)19:2<149::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology. Oxford Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tassone DM, Boyce E, Guyer J, Nuzum D. Clin Ther. 2007;29:26–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey EJ, Reichard GA. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10677–10678.Masse CE, Morgan AJ, Adams J, Panek JS. Eur J Org Chem. 2000:2513–2528.Fukuda N, Sasaki K, Sastry TVRS, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Org Chem. 2006;71:1220–1225. doi: 10.1021/jo0524223.Wardrop DJ, Bowen EG. Chem Commun. 2005:5106–5108. doi: 10.1039/b508300a.For a review of lactacystin syntheses, see: Shibasaki M, Kanai M, Fukuda N. Chem Asian J. 2007;2:20–38. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600310.

- 4.For SmI2-promoted nitrone additions to unsaturated esters/amides, see: Masson G, Cividino P, Py S, Vallée Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:2265–2268. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250480.Riber D, Skrydstrup T. Org Lett. 2003;5:229–231. doi: 10.1021/ol027386y.For lithio-homoenolate additions to N-phenyl imines, see: Katritzky AR, Feng DM, Lang HY. J Org Chem. 1997;62:706–714. doi: 10.1021/jo961396t.Alonso E, Ramon DJ, Yus M. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:2641–2652.

- 5.(a) Chan A, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2005;7:905–908. doi: 10.1021/ol050100f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Phillips EM, Wadamoto M, Chan A, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:3107–3110. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chan A, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5334–5335. doi: 10.1021/ja0709167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wadamoto M, Phillips EM, Reynolds TE, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10098–10099. doi: 10.1021/ja073987e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstein C, Glorius F. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461572.Sohn SS, Rosen EL, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14370–14371. doi: 10.1021/ja044714b.He M, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2005;7:3131–3134. doi: 10.1021/ol051234w.Nair V, Vellalath S, Poonoth M, Mohan R, Suresh E. Org Lett. 2006;8:507–509. doi: 10.1021/ol052926n.For an excellent recent review of NHC catalysis, see: Enders D, Niemeier O, Henseler A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5606–5655. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z.

- 7.Gothelf KV, Jørgensen KA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:863–909. doi: 10.1021/cr970324e.Jen WS, Wiener JJM, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9874–9875.For recent examples of [3 + 3] formal cycloadditions of nitrones, see: Young IS, Kerr MA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:3023–3026. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351573.Sibi MP, Ma ZH, Jasperse CP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5764–5765. doi: 10.1021/ja0421497.Shintani R, Park S, Duan W-L, Hayashi T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5901–5903. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701529.

- 8.The hydroxyl amine products are stable when stored at −20 °C, but slowly decompose at 23 °C.

- 9.Relative and absolute configuration of 7 was determined by X-ray crystallography; see Supporting Information for details. Additional stereochemistry assigned by analogy.

- 10.For a racemic synthesis of 17, see ref 4c.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.