Abstract

The authors investigated discrepancies in arrest rates between Black and White male juveniles by examining the role of early risk factors for arrest. Two hypotheses were evaluated: (a) Disproportionate minority arrest is due to increased exposure to early risk factors, and (b) a differential sensitivity to early risk factors contributes to disproportionate minority arrest. The study included 481 Black and White boys who were followed from childhood to early adulthood. A higher incidence of early risk factors accounted for racial differences related to any juvenile arrest, as well as differences in violence- and theft-related arrests. However, increased exposure to early risk factors did not explain race differences in drug-related arrests. Minimal support was found for the hypothesis that a differential sensitivity to risk factors accounts for disproportionate rate of minority male arrests. In sum, most racial discrepancies in juvenile male arrests were accounted for by an increased exposure to childhood risk factors. Specifically, Black boys were more likely to display early conduct problems and low academic achievement and experience poor parent–child communication, peer delinquency, and neighborhood problems, which increased their risk for juvenile arrest.

Keywords: juvenile arrest, racial discrepancies, risk factors

When examining arrest rates, one finds racial discrepancies that cannot be ignored (Beckett, Nyrop, Pfingst, & Bowen, 2005; Krueger, Bond Huie, Rogers, & Hummer, 2004; Lauritsen, 2005; Ramchand, Pacula, & Iguchi, 2006). Specific to juvenile arrest, evidence suggests that Black youths are up to 3 times more likely to be arrested than White youths (Huizinga et al., 2007). Although many have speculated about the origins of racial discrepancies in juvenile arrest, few have empirically evaluated potential explanations of these discrepancies (Kempf-Leonard, 2007). In the current study, we evaluated two potential explanations of racial discrepancies in juvenile male arrest using prospective information collected on child internalizing and externalizing behavior and con textual risk factors.

One primary hypothesis in the literature is that racial discrepancies in arrest rates occur as a byproduct of Black youths displaying and experiencing more risk factors for arrest across multiple domains (Kempf-Leonard, 2007; Moffitt, 1994). Increased exposure to risk models propose that environmental and societal inequalities (e.g., poor health care and educational systems) cause Black youths to exhibit more adverse individual risk factors, which then leads to a greater probability for arrest. Along these lines, risk factors across multiple domains have been linked to juvenile arrest (Loeber et al., 2005), and many of these risk factors are more prevalent among Black versus White youths (Piquero, Moffitt, & Lawton, 2005). In terms of risk for arrest, child problem behavior, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems (Lahey et al., 1999), conduct problems (Hanson et al., 1984), oppositional defiant problems (Lahey et al., 1999), affective problems (Loeber et al., 2005), low anxiety (Tremblay, Pihil, Vitaro, & Dobkin, 1994), and interpersonal callousness (Loeber et al., 2005) have been associated with juvenile arrest. Additional factors such as family socioeconomic status (SES; Bynum & Thompson, 1999; Patterson & Yoerger, 2002), poor parent–child communication (Hanson et al., 1984; Loeber et al., 2005), physical punishment (Loeber et al., 2005), peer delinquency (Felson, 1998; Hanson et al., 1984; Patterson & Yeorger, 2002), peer rejection (Hanson et al., 1984), low academic achievement (Herrenkohl, Hawkins, Chung, Hill, & Battin-Pearson, 2001), and neighborhood problems (Bynum & Thompson, 1999; Felson, 1998; Piquero, Moffitt, & Lawton, 2005) have also been associated with arrest.

In some preliminary studies, researchers have statistically evaluated risk factors and suggested that exposure to high levels of risk factors may account for racial discrepancies in arrest (Krueger et al., 2004). However, few studies have simultaneously examined risk factors across multiple domains in childhood prior to the onset of first arrest (Piquero et al., 2005; Sampson, Morenoff, & Raudenbush, 2005). Considering an array of risk factors assessed in childhood makes it possible to identify the primary factors that may account for racial discrepancies in arrest (Kempf-Leonard, 2007). This information could then be used to refine early prevention strategies designed to target specific factors that increase child’s risk for juvenile arrest. One way to evaluate whether specific risk factors significantly account for racial discrepancies in arrests is through the use of indirect effects models (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Indirect effects models can be used to statistically evaluate whether the influence of race on arrests can be accounted for by the influence of specific early risk factors as well as to determine the proportion of the race effect that is accounted for by specific risk factors. Thus, the current study examined which risk factors best explained racial discrepancies in juvenile male arrest rates through the use of indirect effects models.

In addition to increased exposure to risk models, other theories have suggested that disproportionate minority arrest rates may be accounted for by a differential sensitivity to early risk factors between Black and White youths. These differential sensitivity models suggest that the exclusionary practices associated with institutionalized racism may leave Black juveniles more sensitive to risk factors than White juveniles (Piquero et al., 2005). For example, longitudinal evidence indicates that the negative impact of physically abusive parenting practices on behavior may be more pronounced in Black than in White children (Lansford et al. 2002). However, studies examining the association between less severe forms of physical discipline and conduct problems in the two racial groups have produced mixed findings (Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2004; Pardini, Fite, & Burke, 2008). Thus, there is some preliminary evidence, particularly in regard to physical discipline, to suggest differential sensitivity to risk factors between Black and White youths. However, research examining whether differential sensitivity plays a role in racial discrepancies in arrest rates is needed. One way to examine differential sensitivity is to examine whether the association between risk factors and arrest statistically differ among racial groups (Aiken & West, 1991). Accordingly, we investigated the differential sensitivity hypothesis of racial discrepancies by examining whether relations between risk factors and arrest rates varied across racial groups.

The Current Study

In sum, we sought with the present study to better understand discrepancies in arrest rates between Black and White male juveniles by examining the role of individual (i.e., inattention/hyperactivity, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct problems, affective problems, anxiety problems, interpersonal callousness, and low academic achievement) and contextual risk factors (i.e. family SES, poor parent–child communication, physical punishment, peer delinquency, peer rejection, neighborhood SES, and neighborhood problems). Two hypotheses were evaluated: (a) A differential exposure to early risk factors accounts for differences in arrest rates between Black and White male juveniles, and (b) differential sensitivity to early risk factors accounts for the discrepancy in arrest rates among male juveniles. To examine these questions, we used risk factors that had been measured in children in the second grade to predict juvenile arrest when they were 10–17 years old. The current study examined any juvenile arrest, along with domain-specific arrests (i.e., violence-related, theft-related, and drug-related), given that different types of delinquency may be influenced by divergent causal mechanisms (Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & White, 2008). In this study, we extend previous research by prospectively predicting arrest throughout adolescence, including risk factors across multiple - domains, examining multiple types of offenses, and comparing differential sensitivity and differential risk explanations. Associations were examined in a community-recruited sample of boys with an oversampling of high-risk boys in order to ensure variability in study constructs.

Method

Participants

Participants for the current study consisted of the boys in the youngest cohort of the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS; Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1998), a community sample of inner-city boys. Participants were recruited from first graders attending the Pittsburgh public schools in 1987–1988. A multi-informant (i.e., parent, teacher, child report) screening measure of antisocial behavior was used to increase the number of high-risk males included in the PYS. Those boys scoring within the upper 30% of antisocial behavior and an approximately equal, number of boys randomly selected from the remainder were followed longitudinally. The participation rate of selected families was 84.6%. Boys in the initial recruiting sample were similar to boys in the longitudinal follow-up sample in terms of race, age, family composition, and parental education level (for details, see Loeber et al., 1998). Descriptive statistics for study predictors based on race and risk status are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (Means and Standard Deviations) for Arrest Predictor Variables by Race and Risk Screening Score

| Predictors | White boys |

Black boys |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non–high screen |

High screen |

Non–high screen |

High screen |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Inattention/hyperactivity | 7.06 | 4.99 | 10.92 | 5.11 | 8.94 | 4.35 | 11.66 | 5.11 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 3.21 | 2.04 | 5.26 | 2.29 | 3.20 | 2.11 | 4.85 | 2.45 |

| Conduct problems | 1.24 | 1.77 | 3.86 | 3.29 | 2.28 | 3.09 | 4.52 | 3.84 |

| Affective problems | 1.73 | 2.08 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 1.70 | 1.93 | 1.88 | 2.16 |

| Anxiety problems | 1.50 | 1.73 | 1.96 | 1.60 | 1.38 | 1.53 | 1.64 | 1.78 |

| Interpersonal callousness | 2.58 | 2.79 | 5.68 | 3.86 | 3.38 | 2.83 | 5.77 | 3.72 |

| Low academic achievement | 1.79 | 0.54 | 1.99 | 0.57 | 2.05 | 0.56 | 2.25 | 0.59 |

| Family SES | 38.94 | 10.88 | 37.95 | 13.70 | 34.09 | 12.08 | 31.09 | 13.09 |

| Poor communication | 25.19 | 3.75 | 27.37 | 4.66 | 27.50 | 4.20 | 28.87 | 5.00 |

| Physical punishment | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.38 |

| Peer delinquency | 2.82 | 3.23 | 5.03 | 5.05 | 4.69 | 3.85 | 7.19 | 4.88 |

| Peer rejection | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.46 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | −0.13 | 0.61 | −0.07 | 0.59 | 2.57 | 1.66 | 2.63 | 1.56 |

| Neighborhood problems | 19.91 | 4.30 | 22.11 | 6.32 | 28.98 | 9.15 | 28.81 | 9.29 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

Procedures

Interviews were conducted with the boys and their primary caretakers typically in their homes. Prior to assessment, informed written consent was obtained from caretakers (Loeber et al., 1998). Data collection procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Risk factors were assessed when participants were in second grade, and arrest outcomes were assessed when participants were between 10 and 17 years old.

Measures

Child’s race

A caretaker-reported demographic questionnaire (Loeber et al., 1998) was used to collect information regarding the child’s race (i.e., “What is the child’s race?”). Caretakers chose from one of five categories: White (N = 202), Black (N = 279), Hispanic, (N = 1), Asian (N = 9), and other racial heritage (N = 13). Because the number of children in other racial groups was minimal, only children who were White or Black were included in analyses.

Externalizing behavior problems

The current study included four facets of externalizing problems: conduct problems (CP; 8 items assessing behaviors such as fighting, stealing, and destroying - others’ property), oppositional defiant problems (ODP; 5 items assessing behaviors such as arguing and being defiant), attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems (ADHP; 11 items assessing impulsive behavior, restlessness, and inattention), and interpersonal callousness (IC; 8 items assessing behavior such as being manipulative and showing no guilt after misbehaving). Constructs were created from items on an extended version of the caretaker-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and the Teacher Report Form (TRF), with the higher of the two informants’ ratings being used (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986). Many of the items included in the CP, ODP, and ADHP scales have been rated by clinicians as being very consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (4th ed.; DSM–IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) conceptualizations of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, respectively (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2001, 2003). The IC scale was designed to assess the interpersonal and affective features associated with psychopathy in youths (Pardini & Loeber, 2008; Pardini, Obradovic, & Loeber, 2006). Confirmatory factor analysis has supported the construct validity of the CP, ODP, ADHP, and IC scales across all three cohorts of the PYS, and each of these scales was significantly correlated with persistent delinquent behavior across a 3-year follow-up period (for details, see Pardini, Obradovic, & Loeber, 2006). Moderate to high internal consistency was obtained for the CP (α = .87), ODP (α = .79), ADHP (α = .89), and IC (α = .86) scales.

Internalizing problems

The DSM–IV–oriented scales of anxiety problems (nine items assessing the presence of fears and nervous behaviors) and affective problems (six items assessing the presence of sadness and self-injurious behavior) from the caretaker-reported CBCL were used to measure facets of internalizing problems. These items were rated by clinicians as being very consistent with DSM–IV conceptualizations of childhood anxiety and depressive disorders, respectively (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2001; 2003). Internal consistencies of the affective problems (α = .59) and anxiety problems (α = .57) scales were low in the current study.

Family socioeconomic status (SES)

A caretaker-reported demographic questionnaire (Loeber et al., 1998) was used to collect information regarding family characteristics. Information on caretakers’ educational attainment and current occupation were used to calculate the Hollingshead Index of Socioeconomic Status (Hollingshead, 1975).

Poor parent–child communication

We used the 18 items from the Revised Parent–Adolescent Communication Form (RPACF; Loeber et al, 1998) to assess the parents’ communication style with their child and gauge how often the caregivers discussed issues with their child in an open and supportive manner. Parents responded to each item using a 3-point scale (0 = almost never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = always). Items were coded such that high scores represented poor parent–child communication. Internal consistency of the scale was moderate (α = .74).

Physical punishment

One item from the Discipline Scale (Loeber et al, 1998) was used to examine physical punishment (“If your son does something that he is not allowed to do or that you don’t like, do you slap or spank him, or hit him with something?”). Caretakers responded using a 3-point Likert scale (1= almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often). Because only 6.2% of caretakers responded with often, we dichotomized the item by combining the sometimes and often categories.

Peer delinquency

The Peer Delinquency Scale (PDS; Loeber et al, 1998) was used to measure affiliation with deviant peers. The PDS includes nine items assessing delinquent acts such as stealing. Boys rated how many of their friends had engaged in the acts over the past 6 months using a 4-point scale (0 = none of them, 4 = all of them). Internal consistency of the scale was moderate (α = .79).

Peer rejection

This scale consists of four items administered to both caretakers and teachers as part of the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991) and TRF (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986), respectively. The items assess the child’s tendency to be disliked, teased, and ridiculed by their peers. Internal consistency for the scale was adequate (α = .73).

Low academic achievement

Four items administered as part of the TRF (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986) were used to assess academic achievement. Teachers rated the child’s overall performance on four different subjects (i.e., reading, writing, math, spelling) using a 4-point scale (ranging from well below average to well above average). Items were recoded such that higher scores represented lower levels of academic achievement. The scale had high internal consistency (α = .91).

Neighborhood SES disadvantage

Neighborhood SES disadvantage scores were derived from a principal components factor analysis of 1990 U.S. Census tract data of Pittsburgh neighborhoods (Wikström & Loeber, 2000). Each participant was assigned a neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage factor score based on the neighborhood in which he lived at the first follow-up assessment. High scores represent high neighborhood SES disadvantage.

Neighborhood problems

A 17-item caretaker-reported Neighborhood Scale was used to assess neighborhood problems such assaults, drug dealing, and vandalism (Loeber et al., 1998). For each item, caretakers indicated the severity of the problem using a 3-point scale (1 = not a problem, 3 = a big problem). This measure exhibited high internal consistency (α = .91).

Juvenile arrest

Two court sources were used to gather information on juvenile arrest charges. Information on juvenile offenses within Allegheny County prior to 2001 was collected from Allegheny County Juvenile Court records (participants were 10–17 years old). In addition, the Pennsylvania Juvenile Court Judges’ Commission provided data on juvenile offenses throughout Pennsylvania up to 1997 (participants were 10–16 years old). In order to prevent double-counting of charges found across both data sources, we examined dates of arrest so that any charge that was registered on the same date across both sources was counted only once. For the present study, we examined outcomes related to the presence of any type of criminal charge as a juvenile (i.e., 0 = no charges, 1 = 1 or more charges), as well as three different dichotomous categories of charges: violence-, theft-, and drug-related arrests. Arrest for violence was coded positive if the participant had any charges for crimes against another person that involved the use of force or threat of force (e.g., homicide, robbery). Theft arrest was coded positive if the participant had any charges related to the illegal procurement or possession of property without the owner’s consent that did not involve the use of force or threats of force (e.g., burglary, larceny), while drug-related arrest was coded positive for participants who had any charge related to the possession of drug paraphernalia and illegal substances, as well as drug dealing.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 4.2 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). As recommended in the literature, all predictor variables were standardized prior to the primary analyses in order to aid our interpretation of the findings (Aiken & West, 1991). Due to the dichotomous nature of the arrest variables, weighted least squares estimation with a mean and variance adjusted chi-square statistic (WLSMV) was utilized in the current study. WLSMV provides unbiased estimates, standard errors, and model fit tests for dichotomous data (Muthén, 1984). This estimator uses a standard error, mean, and variance adjusted chi-square test statistic, which is appropriate for non-normally distributed data (Muthén, 1984; Muthén & Muthén, 2006). The weighted root-mean-square residual (WRMR) statistic was used to evaluate model fit, with a WRMR value of less than .90 suggesting the model provided good fit to the data (Yu & Muthén, 2001).

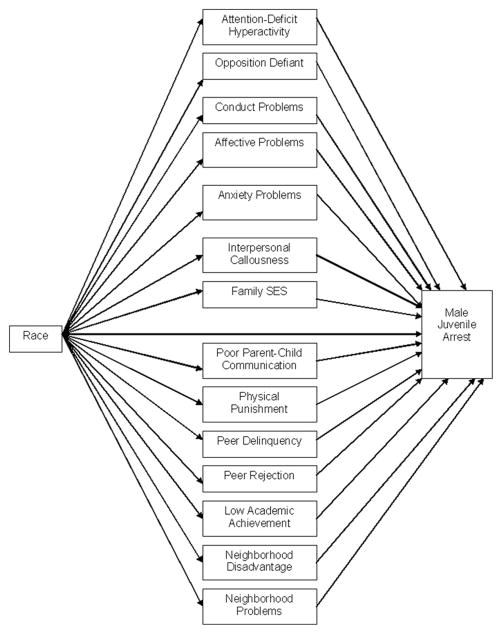

Empirical evaluation is required to determine whether risk factors account for the relation between race and arrests. It is not enough to simply add risk factor variables to the model (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Accordingly, we used indirect effect models to evaluate whether increased exposure to risk factors accounted for the significant relation between race and juvenile arrest. First, we estimated the bivariate relation between race and the outcome of arrest by estimating models that regressed arrest onto race. Next, analyses were conducted to determine whether a disproportionate exposure to risk factors could statistically account for the association between race and arrest (i.e., race has an indirect effect on arrest), as well as to determine the proportion of the race effect accounted for by specific risk factors. For these indirect effect models, regression paths from race to each of the risk factors and from each risk factor and race to arrests are estimated simultaneously within the model (See Figure 1). These models allow one to determine whether the risk factors completely account for the significant relation between race and arrests. If race is no longer a significant predictor of arrests after the inclusion of the risk factors in the model, then it suggests that race only indirectly affects arrest through its relation with one or more risk factors in the model. More specifically, we used the bias-corrected bootstrap method to test indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2004). This method has been found to provide a more accurate balance between Type 1 and Type 2 errors than other methods used to test for indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2004). The bias-corrected bootstrap method provides a more accurate test of indirect effects by correcting for bias in the estimate of the central tendency through resampling to account for the nonnormal distribution of the indirect effect (Bollen & Stine, 1990; MacKinnon et al., 2004). Five hundred bootstrap samples and the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were used to test the significance of indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Heuristic of indirect effects model. The paths from race to each risk factor and juvenile arrest should not be interpreted as causal mechanisms. SES = socioeconomic status.

To further evaluate the magnitude of the indirect effects, we calculated the percentage of the total effect of race on arrest that was accounted for by each significant risk factor, as well as all significant risk factors together (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993). Specifically, we divided the estimated indirect effect for each significant risk factor, as well as the sum of the indirect effects for all significant risk factors, by the regression parameter representing the association between race and arrest without the risk factors in the model.

Odds ratios for the relation between the risk factors and arrest are also reported in order to allow evaluation of the magnitude of associations between the risk factors and arrests. Odds ratios greater than 1 suggest an increase in odds of the outcome per 1 standard deviation increase in the independent variable, and odds ratios less than 1 indicate a decrease in odds of the outcome per each standard deviation increase in the independent variable (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

Overarching models in which all the potential risk factors were included were first estimated in order to establish which risk factors uniquely account for racial differences in arrest. Individual models for each risk factor were then estimated in order to provide follow-up analyses of which risk factors accounted for racial differences in arrest when considered individually.

Note that some investigators have found that child reports of peer delinquency may be a reflection of the child’s own antisocial behavior rather than the behavior of their peers per se (e.g., Haynie & Osgood, 2005). Moreover, the association between conduct problems and arrest most likely reflects continuity of problem behavior over time, as many conduct problems seen in children in the second grade would be grounds for arrest if exhibited by older adolescents. As a result, including these variables in the model may attenuate the indirect effects of other risk factors on relations between race and arrests. To examine the influence of these variables on the results, we re-estimated the overarching increased exposure to risk models without child conduct problems and child-reported peer delinquency in the model. Additionally, a combined parent and teacher scale of deviant peer affiliation was included in the model in lieu of the child self-reported variable to determine whether associations were due to the use of child reports of peer delinquency.

We then tested differential sensitivity effects by examining whether associations between risk factors and arrest varied as a function of race using a multiple group model approach (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). An unrestricted model, in which relations were allowed to vary freely across the racial groups was first estimated. Next, a model in which associations between risk factors and arrest were constrained to be equal across the racial groups was estimated. A diff test procedure was then used to determine whether constraining relations to be equal across the groups resulted in a significant decrement in the model chi-square (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). If constraining relations across the groups resulted in significant decrement in the model chi-square, then findings would suggest that associations varied across the racial groups. The multiple group model strategy was first used to provide overall omnibus tests of whether the 14 risk factors (i.e., a block effect) varied across the racial groups. Then models in which only one risk factor was constrained to be equal across racial groups at a time were estimated in order to provide follow-up analyses of whether there were racial differences in particular risk factors.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 contains the means and standard deviations for all predictor variables by both race and high risk score at screening. Arrest rates for each of the offense categories by race are reported in Table 2. As expected from previous studies, chi-square difference tests indicate that Black youths were significantly more likely to be arrested as juveniles than White youths across all types of arrests. The discrepancy was particularly pronounced for the variable representing any type of criminal charge as a juvenile. Specifically, approximately one half of Black boys in the sample had been charged with a crime as a juvenile, while approximately one third of White boys had a criminal charge as a juvenile.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Age of Onset of Juvenile Arrest for Black and White Boys

| Variable | Full sample (N = 481) |

Black boys (N = 279) |

White boys (N = 202) |

χ2(1, N = 481) | t(219) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | M | SD | % | N | M | SD | % | N | M | SD | |||

| Any arrest | 45.9 | 221 | 56.6 | 158 | 31.2 | 63 | 30.54*** | |||||||

| Violence-related arrest | 29.5 | 142 | 38.4 | 107 | 24.6 | 35 | 24.89*** | |||||||

| Theft-related arrest | 26.8 | 129 | 33.3 | 93 | 27.9 | 36 | 14.36*** | |||||||

| Drug-related arrest | 13.5 | 65 | 19.7 | 55 | 5.0 | 10 | 21.85*** | |||||||

| Age at first arrest | 13.67 | 2.12 | 13.65 | 2.08 | 13.75 | 2.25 | 0.317 | |||||||

p = .001.

Correlations among all study predictors and outcomes are reported in Table 3. Any type of juvenile arrest and violence-related arrests were moderately associated with all risk factors except for affective and anxiety problems. Theft-related arrests were weakly to moderately associated with all risk factors except for affective and anxiety problems, physical punishment, and peer rejection. In contrast, drug-related arrests were weakly to moderately associated with only 5 of the risk factors (i.e., low academic achievement, poor parent–child communication, peer delinquency, neighborhood disadvantage, and neighborhood problems). As anticipated, race was weakly to strongly correlated with 10 of the 14 risk factors, suggesting that Black youths were more likely to display and experience the majority of risk factors than White youths. This increased level of risk among Black boys was present across multiple domains, including individual (e.g., conduct problems), school (e.g., low academic achievement), family (e.g., poor parent–child communication), peer (e.g., peer delinquency), and community-level (e.g., neighborhood problems) risk factors.

Table 3.

Correlation, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Race | — | — | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Any arrest | .25* | — | — | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Violent arrest | .23* | .70* | — | — | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Theft arrest | .17* | .66* | .46* | — | — | — | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Drug arrest | .21* | .43* | .33* | .27* | — | — | — | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Inattention/hyperactivity | .15* | .20* | .16* | .09* | .03 | — | 4.87 | 2. | |||||||||||||

| 7. Oppositional/defiant | −.02 | .21* | .14* | .12* | .01 | .61* | — | 4.12 | 2. | ||||||||||||

| 8. Conduct problems | .15* | .32* | .27* | .21* | .09 | .58* | .69* | — | 3.07 | 3. | |||||||||||

| 9. Affective problems | −.06 | .05 | .02 | .00 | .03 | .25* | .29* | .24* | — | 1.91 | 2. | ||||||||||

| 10. Anxiety problems | −.06 | .00 | −.04 | −.04 | −.02 | .26* | .26* | .20* | .52* | — | 1.60 | 1. | |||||||||

| 11. Interpersonal callousness | .09 | .22* | .16* | .13* | .03 | .66* | .66* | .68* | .23* | .28* | — | 4.42 | 3. | ||||||||

| 12. Low acad. achievement | .20* | .22* | .23* | .15* | .13* | .42* | .18* | .23* | −.03 | −.02 | .20* | — | 2.16 | 0. | |||||||

| 13. Family SES | −.23* | −.23* | −.17* | −.24* | −.09 | −.12* | −.13* | −.15* | −.04 | .05 | −.08 | −.18* | — | 34.98 | 12. | ||||||

| 14. Poor communication | .22* | .28* | .27* | .18* | .11* | .26* | .18* | .23* | .17* | .10* | .21* | .22* | −.29* | — | 27.40 | 4. | |||||

| 15. Physical punishment | .10* | .15* | .14* | .08 | .05 | .20* | .14* | .12* | .05 | −.03 | .13* | .13* | −.09 | .11* | — | 0.73 | 0. | ||||

| 16. Peer delinquency | .24* | .22* | .21* | .10* | .13* | .16* | .15* | .17* | .04 | .02 | .16* | .11* | −.04 | .08 | .12* | — | 5.13 | 4. | |||

| 17. Peer rejection | .12* | .18* | .21* | .08 | .03 | .53* | .55* | .68* | .26* | .25* | .59* | .20* | −.09* | .22* | .04 | .15* | — | 0.42 | 0. | ||

| 18. Neighborhood disadvantage | .72* | .27* | .24* | .20* | .22* | .15* | .05 | .21* | .03 | .01 | .14* | .17* | −.28* | .23* | .08 | .21* | .14* | — | 1.46 | 1. | |

| 19. Neighborhood problems | .45* | .20* | .24* | .09* | .19* | .14* | .11* | .18* | .12* | .11* | .14* | .10* | −.22* | .28* | .08 | .11* | .17* | 0.53* | — | 25.55 | 8. |

Note. Acad. = academic; SES = socioeconomic status.

p < .05.

Increased Exposure to Risk

Juvenile arrest

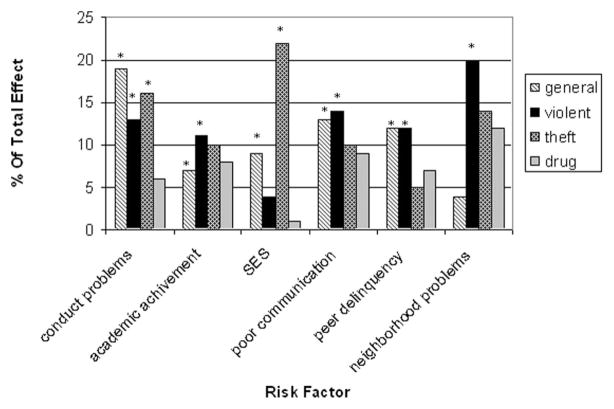

In the initial bivariate model examining the relation between race and general arrest (WRMR = .000), race emerged a significant predictor of arrest (B = 0.33, p < .05; R2 = .10). Specifically, Black youths were more likely to be arrested than White youths. All potential risk factors were then added to the model (WRMR = .081; see Table 4 for all path estimates). Specifically, paths from race to each of the risk factors, as well as paths from each of the risk factors and race to arrest, were estimated simultaneously. In this model, race was no longer a significant predictor of juvenile arrest (B = 0.07, p = .44). Indirect effects analysis indicated that peer delinquency (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.08; % indirect effect [IE] = 12%), conduct problems (B = 0.06, 95% CI = .02–.12; IE = 19%), SES (B = 0.03, 95% CI = .03–.07; IE = 9%), poor communication (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.08; IE = 13%), and low academic achievement (B = 0.02, 95% CI = .002–.060; IE = 7%) significantly accounted for the relation between race and any juvenile arrest. Taken together, these significant risk factors accounted for 60% of the total effect between race and general arrest. Figure 2 depicts the percentage of effect between race and any juvenile arrest accounted for by each of the significant individual risk factors.1

Table 4.

Path Estimates and Odds Ratios for Overarching Indirect Effect Arrest Models

| Risk factor | Race → risk factor | Risk factor → general arrest |

Risk factor → violent arrest |

Risk factor → theft arrest |

Risk factor → drug arrest |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path est. | Odds ratio | Path est. | Odds ratio | Path est. | Odds ratio | Path est. | Odds ratio | ||

| ADHD | .15* | −.11 | .90 | −.11 | .90 | −.15 | .86 | −.16 | 0.85 |

| Oppositional defiant | −.02 | −.01 | .99 | −.04 | .96 | .03 | 1.03 | −.04 | 0.96 |

| Conduct problems | .15* | .42* | 1.52 | .27* | 1.31 | .26* | 1.30 | .16 | 1.17 |

| Affective problems | −.06 | −.01 | .99 | −.02 | .98 | −.02 | .98 | .09 | 1.09 |

| Anxiety problems | −.06 | −.04 | .96 | −.10 | .90 | −.04 | .96 | −.05 | 0.95 |

| Interpersonal callousness | .09† | .03 | 1.03 | −.03 | .97 | .06 | 1.06 | −.00 | 1.00 |

| SES | −.23* | −.13* | .88 | −.06 | .94 | −.23* | .79 | −.01 | 0.99 |

| Poor communication | .22* | .19* | 1.21 | .20* | 1.22 | .12 | 1.13 | .06 | 1.06 |

| Physical punishment | .10* | .13* | 1.14 | .14* | 1.15 | .06 | 1.06 | .01 | 1.01 |

| Peer delinquency | .24* | .16* | 1.17 | .16* | 1.17 | .05 | 1.05 | .12 | 1.13 |

| Peer rejection | .12* | −.11 | .90 | .08 | 1.08 | −.11 | .90 | −.07 | 0.93 |

| Low acad. achievement | −.20* | .12† | 1.13 | .17* | 1.19 | .11 | 1.12 | .16 | 1.17 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | .72* | .09 | 1.09 | .02 | 1.02 | .10 | 1.11 | .08 | 1.08 |

| Neighborhood problems | .45* | .03 | 1.03 | .14* | 1.15 | −.07 | .93 | .11 | 1.12 |

Note. All predictors were standardized. Race → risk factor represents relations between race and risk factors. Risk factor → arrest represents relations between the risk factors and arrest. In these multivariate models, nonsignificant paths were found between race and general arrest (B = .07, p = .44), violence-related arrest (B = .06, p = .49), and theft arrest (B = .07, p = .40). However, race significantly predicted drug-related arrest (B = .22, p = .03). Est. = estimate; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SES = socioeconomic status; acad. = academic.

p < .07.

p < .05.

Figure 2.

Percentage of race effect accounted for by individual risk factors. Bars with asterisk above them indicate a statistically significant (p < .05) indirect effect for the risk factor and arrest category listed.

Risk factors were then examined in separate models in order to determine which risk factors significantly accounted for the relation between race and general arrest when considered alone. Consistent with the overarching model, peer delinquency (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .03–.09), conduct problems (B = 0.06, 95% CI = .02–.09), SES (B = 0.06, 95% CI = .03–.09), poor communication (B = 0.07, 95% CI = .04–.11), and low academic achievement (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .02–.08) significantly accounted for the relation between race and any juvenile arrest when considered individually. Additionally, interpersonal callousness (B = 0.02, 95% CI = .003–.050), attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems (B = 0.03, 95% CI = .01–.06), neighborhood problems (B = 0.06, 95% CI = .01–.12), neighborhood SES disadvantage (B = 0.16, 95% CI = .06–.28), and physical punishment (B = 0.02, 95% CI = .003–.050) significantly contributed to the relation between race and juvenile arrest. When examined together in a single model, these 10 risk factors accounted for 72% of the total effect between race and general arrest.

Domain-specific arrest

In the initial model that estimated the relation between race and each of the domain-specific arrests simultaneously (WRMR = .001), race was a predictor of violence-related (B = 0.32, p < .05; R2 = .09), theft-related (B = 0.24, p < .05; R2 = .06), and drug-related (B = 0.39, p < .05; R2 = .13) arrest. Specifically, Black youths were more likely to be arrested for all three types of offenses than White youths. All potential risk factors were then added to the model (WRMR = .073; see Table 4 for all path estimates) to examine whether the association between race and each arrest category could be explained by a differential exposure to risk factors. Specifically, paths from race to each of the risk factors, as well as paths from each of the risk factors and race to each arrest category, were estimated simultaneously. In this model, race was no longer a predictor of violence-related arrest (B = 0.06, p = .49). Indirect effects analysis indicated that conduct problems (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.09; IE = 13%), low academic achievement (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.07; IE = 11%), communication problems (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .02–.08; IE = 14%), peer delinquency (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.08; IE = 12%), and neighborhood problems (B = 0.06, 95% CI = .01–.13; IE = 20%) significantly accounted for the relation between race and violence-related arrest (see Figure 2 for visual presentation of percentage of effect accounted for by significant risk factors). Taken together, these significant risk factors accounted for a combined 70% of the total effect between race and violence-related arrest.

Likewise, race was no longer a predictor of theft-related arrest (B = 0.07, p = .40) in this model. For theft-related arrest, indirect effects analysis indicated that SES (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .03–.10; IE = 22%) and conduct problems (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.09; IE = 16%) significantly accounted for the relation between race and theft-related arrest (see Figure 2 for visual presentation of percentage of effect accounted for by significant risk factors). Taken together, these significant risk factors accounted for a combined 38% of the total effect between race and theft-related arrest.

In contrast to the findings for violence- and theft-related arrest, no risk factors included in the model significantly accounted for the relation between race and drug-related arrest. In fact, after we added the risk factors to the model, only race emerged as significant predictor of drug-related arrest (B = 0.22, p = .03; see Table 4 for all estimated paths).

Risk factors were then examined in separate models in order to determine which risk factors significantly accounted for relations between race and domain-specific arrests when considered alone Consistent with the overarching model, conduct problems (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .02–.08), low academic achievement (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .03–.09), communication problems (B = .07, 95% CI = .04–.11), peer delinquency (B = 0.05, 95% CI = .02–.10), and neighborhood problems (B = 0.10, 95% CI = .05–.16) significantly accounted for the relation between race and violence-related arrest. Additionally, interpersonal callousness (B = 0.02, 95% CI = .001–.04), attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems (B = 0.03, 95% CI = .01–.06), peer rejection (B = 0.03, 95% CI = .01–.06), neighborhood SES disadvantage (B = 0.12, 95% CI = .01–.23), physical punishment (B = 0.02, 95% CI = .002–.050), and SES (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .02–.08) significantly contributed to the relation between race and violence-related arrest. When these 11 risk factors were combined in a single model, they accounted for 72% of the total effect between race and violence-related arrest.

Also consistent with the overarching model, SES (B = 0.07, 95% CI = .04–.11) and conduct problems (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .01–.07) significantly accounted for the relation between race and theft-related arrest. Additionally, low academic achievement (B = 0.03, 95% CI = .01–.08) and communication problems (B = 0.04, 95% CI = .02–.08) significantly contributed to the relation between race and theft-related arrest when factors were examined individually. When combined in a single model, these four risk factors accounted for 47% of the total effect between race and theft-related arrest.

When examined individually, no risk factors were found to significantly account for the relation between race and drug-related arrest. Overall, these findings suggest that a differential exposure to early risk factors included in the current study may not explain the racial discrepancies in drug-related arrest, but exposure to such factors does seem to account for racial differences in violence- and theft-related arrest.

Increased Exposure to Risk: Supplemental Analyses

To examine the influence of conduct problems and child-reported peer delinquency on the results, we re-examined the increased exposure to risk models without these variables in the model. The risk factors that significantly accounted for the association between race and arrest did not change in any of the models, and the direct paths from race to general, theft-related, and violence-related arrests remained nonsignificant. Additionally, we re-estimated each of the models using a combined parent and teacher scale of deviant peer affiliation that was created by summing a single item from the CBCL and TRF, respectively (regarding whether the child associated with children who “get in trouble”). It is important to note that the significant peer delinquency effects that we found using the child-report measure were also significant when the alternative parent- and teacher-report peer deviance scale was used. Overall, this suggests that the reported findings are remarkably stable and robust.

Differential Sensitivity

Juvenile arrest

A multiple group model approach was used to provide an overall omnibus test of whether the association between risk factors and juvenile arrest varied as a function of race. The diff test suggested that associations did not vary as a function of race, Δχ2(12) = 18.29, p = .11. Additionally, the models in which risk factors were examined individually revealed that their effects did not vary by race (ps > .05). These findings suggest that the association between each of the risk factors and general arrests did not significantly differ between Black and White boys.

Domain-specific arrests

The multiple group model used to provide an overall omnibus test of whether the association between risk factors and domain-specific arrests varied as a function of race indicated that the overall pattern of associations between risk factors and arrests did not vary across racial groups, Δχ2(19) = 19.62, p = .42. However, the models in which each risk factor was examined individually suggested racial differences in the relation between physical punishment and violence-related and theft-related arrest, such that physical punishment was significantly associated with an increased risk for violence- and theft-related arrest for Black (Bs = .030 and 0.23, respectively; ps < .03) but not for White boys (Bs − =.11 & −.22, respectively; ps > .19).

Discussion

The current study examined the role of early risk factors in accounting for discrepancies in arrest rates between Black and White boys. In this study, we extended previous research by prospectively predicting arrest throughout adolescence, including risk factors across multiple domains, examining multiple types of offenses, and comparing differential sensitivity and differential risk exposure explanations. Consistent with prior studies, Black boys displayed higher levels of individual risk factors and experienced higher levels of contextual risk factors across multiple domains and were also more likely to be arrested than White boys. Additionally, increased exposure to childhood risk factors across multiple domains accounted for racial differences in later juvenile arrest, particularly for violence- and theft-related arrest. Our findings contribute to a growing literature suggesting that an increased exposure to risk factors accounts for racial discrepancies in several areas of functioning, including educational achievement (e.g., Fryer & Levitt, 2005). While Black boys experienced and exhibited elevations on several risk factors, only a subset of these factors uniquely accounted for racial discrepancies in arrest, providing clearer primary targets for prevention programs in the early elementary school years aimed at reducing disproportionate rates of minority arrest.

Of the variables included in the current study, conduct problems emerged as the most consistent predictor of future arrest for both theft and violence and accounted for nearly one fifth of the discrepancy in general arrest rates between Black and White boys. While it is well known that children who exhibit severe conduct problems are at increased risk for arrest (Hanson et al, 1984; Lahey et al., 1999), it is important to note that other behavior problems did not add to the prediction of arrest when conduct problems and other risk factors were also included in the model. This finding is particularly important given that the DSM–V workgroup on disruptive behavior disorders has stressed the need for studies examining whether behaviors consistent with oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and interpersonal callousness provide any predictive utility for antisocial outcomes above and beyond behaviors associated with conduct disorder (Moffitt et al., 2008). Along these lines, the current results suggest that interventions aimed at preventing juvenile arrest should target young boys exhibiting early signs of conduct disorder above all other forms of internalizing and externalizing behavior. Because low levels of academic achievement also uniquely accounted for the increased risk for later violence-related arrest, intervention programs designed for children exhibiting co-occurring conduct disorder symptoms and academic problems will likely have the greatest impact on disproportionate minority arrest rates.

Contextual risk factors in childhood also accounted for disproportionate male minority arrest rates, although there was variation in which factors were most important depending on the type of arrest examined. Boys who were exposed to conflicted parent–child interactions and who affiliated with delinquent peers were at relatively high risk for later arrest, especially for violence. Exposure to these two social factors accounted for 26% of the observed racial discrepancy in violence-related arrests. Exposure to increased levels of neighborhood problems emerged as the most important factor for explaining the increased risk for violence related arrests in Black boys, accounting for an additional 20% of the observed race effect. In contrast, SES was the most important factor for explaining disproportionate minority arrest for theft in boys but was not uniquely related to arrest for violence. Overall, findings suggest that efforts to eliminate disproportionate minority arrest rates should involve targeting multiple social systems.

Exposure to high levels of risk factors examined in the current study did not account for racial differences in drug-related arrest There is evidence to suggest that Black youths are more likely to obtain and use substances in more public places, where police officers are more abundant and individuals are more likely to get caught (Beckett et al., 2005; Ramchand et al., 2006), which could explain racial discrepancies. Along the same lines, Coker (2003) proposed that Black individulas are more likely to be stopped for traffic offenses and, when stopped, to have their cars are searched by police for evidence of more criminal activity (i.e., drug possession) that leads to arrest. Additionally, other risk factors (e.g. parental substance use) not assessed in the current study or more proximal predictors (e.g., substance use or peer relationships just prior to the time of arrest) may better account for drug-related arrest than the more distal predictors examined in the current study. However, further research is needed to determine which of these explanations best accounts for the racial discrepancies in drug-related arrest.

The current study found little support for the notion that disproportionate minority arrest rates can be explained by a differential sensitivity to certain risk factors. The sole exception was that exposure to physical punishment was related to violence- and theft-related arrests for Black, but not for White, boys. Although these findings are consistent with previous research using the PYS (Pardini et al., 2008), other investigators have suggested that physical punishment may actually reduce behavior problems in Black boys (Lansford et al., 2004). It seems unwise to view physical punishment in Black families as a beneficial parenting practice since it was associated with an increased risk for future arrest in the current study.

With regard to intervention, these findings stress the need for early multifaceted interventions that target both individual and contextual factors. Indeed, interventions that target multiple domains are more efficacious than interventions that target only one aspect of risk (Foster & Olchowski, 2007; Lochman & Wells, 2004). While findings suggest that the same factors should be the targets of intervention for both Black and White boys, Black boys are more likely to have individual risk factors and experience multiple contextual risk factors associated with arrest. An increased focus on effective prevention programs within schools and community-based organizations that predominately serve Black families is indicated. Along these lines, the Pennsylvania Department of Health (2008) recently provided funding to implement an empirically based prevention program called Stop Now and Plan (SNAP) (Webster, Augimeri, & Koegl, 2002) for boys exhibiting significant conduct problems within the city of Pittsburgh. The goal of the intervention is to prevent arrest by targeting many of the risk factors that accounted for the disproportionate minority arrest rates found in the current study. The intervention will be implemented by community-based organizations that disproportionately serve Black families. As a result, we are hopeful that this program will be a positive step toward eliminating the racial discrepancies in arrest in the Pittsburgh area.

Findings may also have implications for the juvenile justice system. Black youths in the juvenile court system may be particularly in need of further assessment to determine what additional services may be needed to overcome early risk factors. Additionally, one interpretation of findings is that there is little evidence of racial bias in arrest, at least for non-drug-related arrests. However, this interpretation may be a bit deceptive, as one of the leading offenses for juvenile arrest is drug-related crime (Lauritsen, 2005). Black youths are far more likely to be arrested for drug offenses than White youths, despite evidence suggesting similar rates of use among White and Black youths (Beckett, Nyrop, & Pfingst, 2006; Ramchand et al., 2006).

Limitations

There are several noteworthy limitations of the current study. First, the sample was comprised of boys, and therefore findings should not be generalized to girls. This sample was a community-recruited sample with an oversampling of high-risk boys, which likely resulted in elevated arrest rates when compared with a representative community sample. Additionally, this study examined discrepancies in arrest rates between Black and White boys, and findings may not translate to other racial/ethnic groups. Moreover, findings need to be interpreted in light of the specific risk factors included in the models. Other individual and contextual factors (e.g., malnutrition, parental psychopathology) not examined in this study may also account for racial differences in arrest. There are also likely many proximal predictors (e.g., employment opportunities, educational opportunities, current peer affiliations) that play a role in the likelihood of arrest that were not examined in the current study. Along these lines, it is important to remember that having temporal precedence in longitudinal studies does not ensure causation, and it is likely that a developmental cascade of events starting in early childhood likely precedes juvenile arrest. However, the risk factors identified in the current study may be the early seeds of developmental trajectories that can lead to arrest. Future research examining the pathways through which these early precursors lead to arrest would be useful for further refining prevention strategies. A further measurement limitation is the low to modest internal consistencies of some variables included in the current study. Future studies should include more internally consistent measures. In addition, the current study focused on arrest and not differential treatment between Black and White in terms of sanctions following arrest, which may be influenced by other factors, including discriminatory practices (Kempf-Leonard, 2007). Furthermore, we examined domain-specific arrests by comparing boys who had been arrested for a particular type of offense (e.g., drug-related) with boys who had not been arrested for that specific type of offense, which included those who had not been arrested along with those who had only been arrested for other types of offenses (e.g., violence- and theft-related arrests). This provides information on what risk factors are unique predictors of a particular outcome but does not provide a comparison of those who have been arrested versus those who have not been arrested, and findings need to be interpreted as such.

It is also important to note that caution should be taken when interpreting the effects of peer delinquency and neighborhood problems in the current study. Specifically, peer delinquency may be an indication of a child’s own tendency to seek out antisocial peers rather than a direct influence of peers on the child’s behavior. Research indicates that children tend to select peers who engage in similar levels of antisocial behavior (e.g., Bauman & Ennett, 1994; Hartup, 1995; Haselager, Hartup, van Lieshout, & Riksen-Walraven, 1998) and children who endorse antisocial beliefs may seek out deviant peer groups (Pardini, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2005). In addition, children tend to attribute their own behavior to the behavior of their friends (e.g., Bauman & Ennett, 1994; Haynie & Osgood, 2005). Along similar lines, findings indicating neighborhood problems contribute to the prediction of violent arrest may be the result of differential policing practices in these neighborhoods. It will be important for future research in the area to examine the extent to which other neighborhood characteristics influence arrest across racial groups, as well as to examine whether neighborhood characteristics moderate the effect of risk factors on arrest.

Conclusions

To summarize, findings suggest that increased exposure to early risk factors account for most discrepancies in juvenile arrest rates between Black and White boys, as race was no longer a significant predictor of general, violence-related, or theft-related arrests once risk factors were accounted for in the models. Note that these risk factors can be identified in childhood well before boys can be charged with a crime, emphasizing the importance of early prevention efforts. However, the current study assessed difficulties in the second grade, and environmental processes may have already influenced the development of problem behavior by that time. The current findings should not be interpreted as evidence that being Black causes the development of problem behavior that leads to arrest (Hawkins, 2003). Rather, early environmental factors are likely responsible for the racial differences observed in these risk factors. For example, Moffitt (1994) posited that institutional racism has put Black youths at risk for poor prenatal health care, malnutrition, and exposure to toxins, which can result in psychological problems. Moreover, institutional racism creates undue hardship for Black parents, which can influence parenting and other family characteristics that contribute to the child’s problems. These difficulties are then further compounded by disadvantaged school systems, fewer employment opportunities, poor neighborhood quality, and the like. Thus, the fact that African American boys are at increased risk for experiencing individual and contextual risk factors of arrest suggests the need to also intervene on a larger societal level.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA411018), National Institute on Mental Health (MH 48890, MH 50778), and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (96-MU-FX-0012). Preparation of this article was supported by funding from the National Institute on Mental Health (1K01MH078039-01A1) awarded to Dustin Pardini.

We would like to thank Rolf Loeber and Norm White for their input. Finally, we would like to thank the families who participated in the study.

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

To account for neighborhood differences in arrest rates, we used information on the number of arrests recorded by the police within each Pittsburgh neighborhood at the beginning of the study. Information from the Pittsburgh Department of Public Safety (1988) included the overall number of arrests for Part 1 (e.g., murder, forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary) and Part II offenses (e.g., simple assaults, vandalism, stolen property) within each neighborhood. For each Pittsburgh neighborhood, an arrest rate per 100 inhabitants was calculated to account for population differences across neighborhoods. Although race predicted community-level arrest (B = 0.45, p < .0001), community-level arrest rates were unrelated to arrests (ps = .35–.79). Moreover, the overall pattern of associations remained when we included community-level arrests in analyses. The only indirect effect influenced by inclusion of community-level arrests in the model was neighborhood problems. Neighborhood problems no longer significantly accounted for the relation between race and violence-related arrests. This is likely due to the overlap in the two neighborhood constructs, leaving little unique variance to account for the relation between race and violence-related arrests in the model, as the neighborhood problems variable may be viewed as a caregiver reported measure of crime in the neighborhood, including items such as assault, drug dealing, and vandalism.

Contributor Information

Paula J. Fite, Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee

Porche’ Wynn, Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee.

Dustin A. Pardini, Department of Psychiatry and Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Ratings of relations between DSM–IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6–18, TRF, and YSR. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:328–340. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and teacher version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Testing and interpreting interaction in multiple regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Ennett ST. Peer influence on adolescent drug use. American Psychologist. 1994;49:820–822. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.9.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K, Nyrop K, Pfingst L. Race, drugs, and policing: Understanding disparities in drug delivery arrests. Criminology: An inter disciplinary journal. 2006;44:105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K, Nyrop K, Pfingst L, Bowen M. Drug use, drug possession arrests, and the question of race: Lessons from Seattle. Social Problems. 2005;52:419–444. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Stine R. Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology. 1990;20:115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum JE, Thompson WE. Juvenile delinquency: A sociological approach. 4. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Coker D. Foreword: Addressing the real world of racial injustice in the criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 2003;93:827–880. [Google Scholar]

- Felson M. Crime and everyday life. 2. London: Thousand Oaks; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foster E, Olchowski A, Webster-Stratton C. Is stacking intervention components cost-effective? An analysis of the Incredible Years Program. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 2007;46:1414–1424. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181514c8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer RG, Levitt SD. The Black–White test score gap through third grade. (NBER Working Paper No. 11049) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2005. Available from www.nber.org/papers/w11049. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson CL, Henggler SW, Haefele WF, Roddick JD. Demographic, individual, and family relationship correlates of serious and repeated crime among adolescents and their siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:528–538. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The three faces of friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12(4):569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Haselager GJ, Hartup WW, van Lieshout CF, Riksen-Walraven J. Similarities between friends and nonfriends in middle childhood. Child Development. 1998;69:1198–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DF. Editor’s introduction. In: Hawkins DF, editor. Violent crime: Assessing race and ethnic differences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Osgood DW. Reconsidering peers and delinquency: How do peers matter? Social Forces. 2005;84:1109–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins JD, Chung I, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S. School and community risk factors and interventions. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Child delinquents: Development, intervention, and service needs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 211–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove RL, Hill K, Farrington DP. Disproportionate minority contact in the juvenile justice system: A study of differential minority arrest/referral to court in three cities. A report to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (NCJ Rept. No. 219743) 2007 Retrieved from National Criminal Justice Reference System Web site: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/grants/219743.pdf.

- Kempf-Leonard K. Minority youths and juvenile justice: Disproportionate minority contact after nearly 20 years of reform efforts. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger PM, Bond Huie SA, Rogers RG, Hummer RA. Neighborhoods and homicide mortality: An analysis of race/ethnic differences. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:223–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.011874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID, McBurnett K. The development of antisocial behavior: An integrative causal model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. Racial and ethnic differences in juvenile offending. In: Hawkins DF, Kempf-Leonard K, editors. Our children, their children: Confronting racial and ethnic differences in American juvenile justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR. Violence and serious theft: Development and prediction from childhood to adulthood. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Pardini D, Homish DL, Wei EH, Crawford AM, Farrington DP, et al. The prediction of violence and homicide in young men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;76:1074–1088. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in previous studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Natural histories of delinquency. In: Wietekamp EGM, Kerner HJ, editors. Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, et al. DSM–V conduct disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:3–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical and continuous latent variable indicator. Psychometrika. 1984;49:115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus: The Comprehensive Modeling Program for Applied Researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Fite P, Burke JD. Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and African American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:647–662. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Loeber R. Interpersonal callousness trajectories across adolescence: Early social influences and adult outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35:173–196. doi: 10.1177/0093854807310157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Developmental shifts in parent and peer influences on boys’ beliefs about delinquent behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:299–323. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Obradovic J, Loeber R. Interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, inattention, and conduct problems as precursors to delinquency persistence in boys: A comparison of three grade-based cohorts. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:46–59. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Yoerger K. A developmental model for early-and late-onset delinquency. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyeder J, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pennsylvania Department of Health. Rendell administration announces health research grant from tobacco settlement funds. 2008 Retrieved July 14, 2008 from http://www.dsf.health.state.pa.us/health/cwp/view.asp?A=190&Q=250400.

- Piquero AR, Moffitt TE, Lawton B. Race and crime: The contribution of individual, familial, and neighborhood-level risk factors to life-course persistent offending. In: Hawkins DF, Kempf-Leonard K, editors. Our children, their children: Confronting racial and ethnic differences in American juvenile justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 202–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pittsburgh Department of Public Safety. Police statistical report. Pittsburgh, PA: Author; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Pacula RL, Iguchi M. Racial differences in marijuana-users’ risk of arrest in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Pihil RO, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:732–739. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090064009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster CC, Augimeri LK, Koegl CJ. The under-12 outreach project for antisocial boys: A research-based clinical program. In: Corrado RR, Roesch R, Hart SD, Gierowski JK, editors. Multi-problem violent youth: A foundation for comparative research needs, interventions, and outcomes. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2002. pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström POH, Loeber R. Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents? A study of male juvenile serious offending, individual risk and protective factors, and neighborhood context. Criminology. 2000;38:1109–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Yu CY, Muthén BO. Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes (Technical report) Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles, Graduate School of Education and Information Studies; 2001. [Google Scholar]