Abstract

The desymmetrization of 1,3-diketones using N-heterocyclic carbenes results in the formation of highly enantioenriched cyclopentenes in good yield. The reaction proceeds through a catalytic intramolecular aldol reaction and subsequent β-lactone formation. The expulsion of carbon dioxide at mild reaction temperatures affords the cyclopentene products.

Keywords: carbenes, asymmetric catalysis, Umpolung, β-lactones, aldol reactions

Introduction

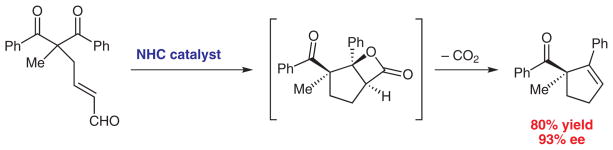

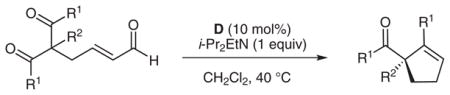

Generating enantioenriched compounds from simple precursors is a persistent goal in organic chemistry.1,2 De-symmetrization reactions of achiral starting materials have become an efficient and topologically interesting approach to produce optically active products.3–6 The utilization of this strategy can be advantageous particularly for the stereoselective formation of quaternary carbon centers.7–9 Herein, we report an efficient and practical method for the construction of α,α-disubstituted cyclopentene rings through an aldol reaction catalyzed by a chiral N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) (Scheme 1).10

Scheme 1.

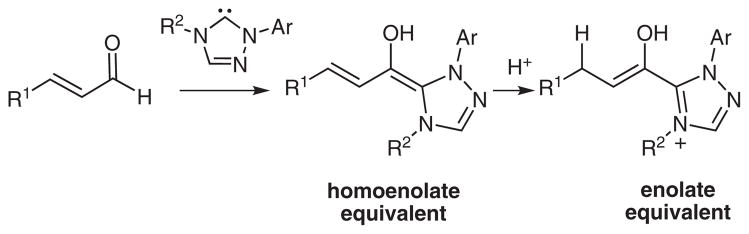

The opportunity to catalyze aldol reactions emerged with our previous studies into NHC-catalyzed processes.11–15 The application of carbene catalysis in these studies involves the protonation of an in situ generated homoenolate to produce a reactive enol intermediate (Scheme 2).16–18 With the appropriate Lewis base precursor (azolium salt) and conditions, the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde can serve as the progenitor for either homoenolate or enolate reactivity.19

Scheme 2.

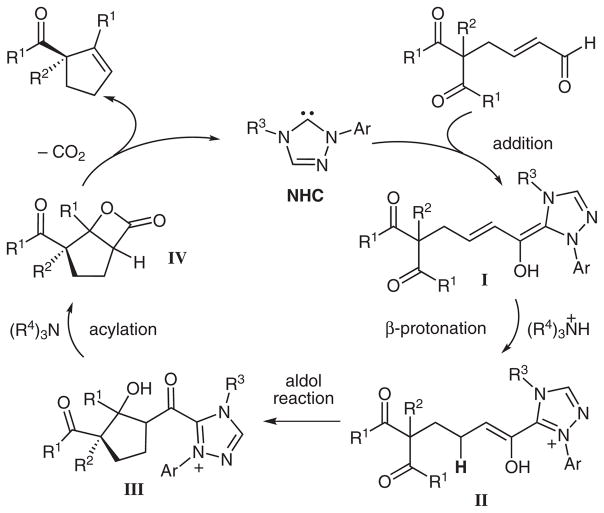

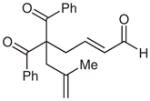

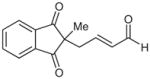

Our goal was to leverage our knowledge of carbene-catalyzed Michael reactions20 to produce an aldol-mediated desymmetrization of 1,3-diketones. In the proposed reaction pathway, β-lactone formation would then regenerate the catalyst followed by a decarboxylation to form enantioenrinched cyclopentenes (Scheme 3).21 The achiral symmetric substrates are readily available from simple palladium(0)-catalyzed alkylations of 1,3-diketones with butadiene monoepoxide followed by oxidation. In this manner, substitution in the 2-position can be varied and the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde is easily appended.

Scheme 3.

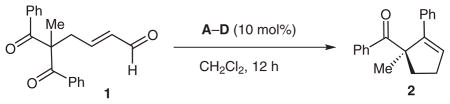

To determine the optimal reaction conditions for this process, several combinations of azolium salts and bases were surveyed. While 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene in conjunction with any pre-catalyst (Table 1, entry 1) does not result in product formation, employment of a stoichiometric amount of N,N-diisopropylethylamine with a triazolium salt is quite successful. A variety of L-phenylalanine-derived azolium salts deliver the cyclopentene product in moderate yield but the selectivity obtained with these salts is not optimal (entries 2–4). Interestingly, employment of pre-catalyst C allows for the synthesis of the opposite enantiomer even though the catalyst structure is still derived from L-phenylalanine. We are investigating this unusual observation and details on this study are forthcoming. Utilization of azolium salt D results in similar yields, but the selectivity of this reaction greatly improves (entry 5). Further investigation revealed that the incorporation of oxygen into the reaction may be affecting the yield of desired compounds due to the isolation of the unsaturated carboxylic acid derived from 1. In order to circumvent this potential problem, dichloromethane and N,N-diisopropylethylamine were degassed prior to use. The interaction of a strongly nucleophilic Lewis base, such as an NHC, and oxygen is indeed plausible.19 To the best of our knowledge, there are no literature examples to date that specifically examine this parameter and report that the exclusion of oxygen directly increases yields using N-heterocyclic carbenes.22 Future carbene catalysis efforts may well be impacted by this curious, yet critical, observation.

Table 1.

Reaction Optimization

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Temp (°C) | Basea | Azolium salt | Yieldb (%) | eec (%) |

| 1 | 23 | DBU | A | 0 | – |

| 2 | 23 | i-Pr2EtN | A | 47 | −83 |

| 3 | 23 | i-Pr2EtN | B | 38 | −76 |

| 4 | 23 | i-Pr2EtN | C | 45 | 51 |

| 5 | 23 | i-Pr2EtN | D | 40 | 94 |

| 6d | 23 | i-Pr2EtN | D | 66 | 94 |

| 7d | 40 | i-Pr2EtN | D | 80 | 93 |

| 8d,e | 40 | i-Pr2EtN | D | 70 | 93 |

1 equiv of base used.

Isolated yields.

Determined by HPLC (Chiralcel OD-H).

Careful exclusion of oxygen.

5 mol% of D.

To our delight, this simple procedure to minimize the oxygen content increased the yield to 66% (entry 6). Finally, slightly heating the reaction ensures that the β-lactone intermediate fully decarboxylates23,24 to form the cyclopentene product in 80% yield (entry 7). Importantly, the increased temperature does not diminish the enantioselectivity of the reaction (93% ee). Decreasing the catalyst loading leads to similar levels of selectivity but lower yields (entry 8).

Scope and Limitations

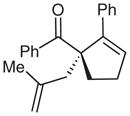

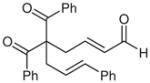

Various 1,3-diketones with different substitution patterns were subjected to the optimal reaction conditions (Table 2). Aryl ketones are good substrates for this process, save for electron-rich aryl ketones (entry 6). We have found that these reactions can be scaled up to produce large amounts of product without diminishing the yield or selectivity (entry 2). Substitution in the 2-position can be varied as well, but the selectivity decreases when the groups become too large. Ethyl groups are accommodated under the reaction conditions with similar enantioselectivity (entry 7). Increasing the size of this group to allyl, methallyl, or cinnamyl groups results in good yields with a small decrease in the levels of selectivity (entries 8–10).

Table 2.

Substrate Scope

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | Cyclopentene | Yielda (%) | eeb (%) |

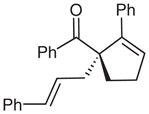

| 1 | Ph | Me | 2 | 80 | 93 |

| 2c | Ph | Me | 2 | 78 | 91 |

| 3 | 4-ClC6H4 | Me | 3 | 76 | 94 |

| 4 | 4-MeC6H4 | Me | 4 | 60 | 94 |

| 5 | 3-MeC6H4 | Me | 5 | 65 | 93 |

| 6 | 4-MeOC6H4 | Me | 6 | <5 | nd |

| 7 | Ph | Et | 7 | 73 | 90 |

| 8 | Ph | allyl | 8 | 70 | 83 |

| 9 |  |

9 |

69 | 83 | |

| 10d |  |

10 |

64 | 82 | |

| 11d |  |

11 |

65e | 93 | |

| 12d |  |

12 |

51e | 96 | |

| 13d |  |

13 |

36e | 15 | |

Isolated yields.

Determined by HPLC; nd = not determined.

Reaction run with 0.50 g of enal 1.

20 mol% of D.

Diastereomeric ratio 20:1. Relative and absolute stereochemistry determined by NOE and X-ray crystallography. See ref. 10 for details.

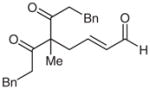

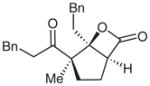

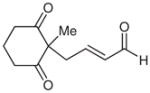

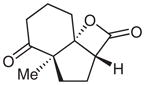

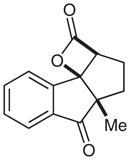

Surprisingly, alkyl ketones allow for the isolation of the β-lactones with excellent diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity (entries 11 and 12). It is interesting to note the favored diastereomer when employing a cyclic or acyclic diketone. The acyclic diketone substrate provides a β-lactone product with the methyl group anti to the tertiary alkoxide (entry 11). However, the relationship is syn with the cyclic diketones (entries 12 and 13). We believe that in these cases, the relative stereochemistry of the methyl group and lactone is determined by the ability of the 1,3-diketone to form a hydrogen-bonded network during the aldol reaction. Unfortunately, indanedione-derived compound 13 was low yielding and had low levels of enantioselectivity (entry 13).

In conclusion, a direct route to highly functionalized cyclopentene rings has been developed. By using a chiral azolium salt as a pre-catalyst, a desymmetrization of 1,3-diketones through a tandem aldol/acylation reaction occurs to form β-lactones. When a decarboxylation is coupled to the desymmetrization event, cyclopentene rings are formed in high yield and enantioselectivity. When alkyl 1,3-diketones are employed, β-lactones can be accessed with excellent levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity. Investigations using carbene catalysis to generate homoenolate and enolate intermediates with unique properties are continuing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Herein we describe the procedure for the desymmetrization of 1,3-diketones catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbenes.

[(R)-1-Methyl-2-phenylcyclopent-2-enyl](phenyl)methanone (2); Typical Procedure

In a glove-box, under inert atmosphere, to a flame-dried round bottom flask equipped with magnetic stirring bar was added azolium salt D (12.6 mg, 0.03 mmol) and enal 1 (92 mg, 0.3 mmol). The flask was sealed with a rubber septum. The flask was charged with degassed CH2Cl2 (6 mL, 0.05 M). Once the material dissolved, degassed i-Pr2NEt (54 μL, 0.3 mmol) was added via syringe. The flask was removed from the glove box and heated to 40 °C under N2 atmosphere for 12 h. The soln was diluted with hexanes (2 mL) and was directly subjected to flash column chromatography (silica gel, 5% to 12% EtOAc–hexanes) to afford 2 (63 mg, 80%) as a colorless oil. For large-scale reactions the material was first washed with sat. aq NH4Cl (20 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 20 mL). The combined organics were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated. The residue was then purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel, 5% to 12% EtOAc–hexanes).

HPLC (Chiralcel OD-H, 3% i-PrOH–hexanes, 1 mL/min): tR = 5.87 (major), 9.22 min (minor).

IR (film): 3057, 2962, 2929, 2847, 1670, 1596, 1496, 1446, 1372, 1261, 1240, 1172, 976, 758, 692 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.98 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.38–7.34 (m, 4 H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 7.15 (m, 1 H), 6.36 (s, 1 H), 2.73–2.60 (m, 3 H), 1.99–1.97 (m, 1 H), 1.55 (s, 3 H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 205.0, 148.6, 137.5, 135.2, 132.0, 129.3, 128.9, 128.7, 128.3, 127.5, 126.5, 62.1, 39.0, 31.1, 24.1.

GC-MS (CI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C19H19O: 263.1; found: 263.0.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by NIH/NIGMS (RO1 GM73072). We thank Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, GlaxoSmith-Kline, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim for generous unrestricted support. We thank FMCLithium, Wacker Chemical Company, Sigma-Aldrich, and BASF for providing reagent support.

References

- 1.Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. 1–3. Springer; Berlin: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ojima I, editor. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YG, McDaid P, Deng L. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2965. doi: 10.1021/cr020037x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.France S, Guerin DJ, Miller SJ, Lectka T. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2985. doi: 10.1021/cr020061a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Urdiales E, Alfonso I, Gotor V. Chem Rev. 2005;105:313. doi: 10.1021/cr040640a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian SK, Chen YG, Hang JF, Tang L, McDaid P, Deng L. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:621. doi: 10.1021/ar030048s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corey EJ, Guzman-Perez A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas CJ, Overman LE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trost BM, Jiang CH. Synthesis. 2006:369. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadamoto M, Phillips EM, Reynolds TE, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10098. doi: 10.1021/ja073987e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattson AE, Bharadwaj AR, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2314. doi: 10.1021/ja0318380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan A, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2005;7:905. doi: 10.1021/ol050100f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maki BE, Chan A, Phillips EM, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2007;9:371. doi: 10.1021/ol062940f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan A, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4558. doi: 10.1021/ja060833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maki BE, Chan A, Scheidt KA. Synthesis. 2008:1306. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeitler K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:7506. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enders D, Niemeier O, Henseler A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5606. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marion N, Diez-Gonzalez S, Nolan IP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2988. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denmark SE, Beutner GL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1560. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips EM, Wadamoto M, Chan A, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3107. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nair V, Vellalath S, Poonoth M, Suresh E. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8736. doi: 10.1021/ja0625677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YK, Li R, Yue L, Li BJ, Chen YC, Wu Y, Ding LS. Org Lett. 2006;8:1521. doi: 10.1021/ol0529905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulzer J, Zippel M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:751. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulzer J, Zippel M. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1981:891. [Google Scholar]