Abstract

The gene bb0250 of Borrelia burgdorferi is a homolog of the dedA family, encoding integral inner membrane proteins that are present in nearly all species of bacteria. To date, no precise function has been attributed to any dedA gene. Unlike many bacterial species, such as Escherichia coli, which has eight dedA genes, B. burgdorferi possesses only one, annotated bb0250, providing a unique opportunity to investigate the functions of the dedA family. Here, we show that bb0250 is able to restore normal growth and cell division to a temperature-sensitive E. coli mutant with simultaneous deletions of two dedA genes, yqjA and yghB, and encodes a protein that localizes to the inner membrane of E. coli. The bb0250 gene could be deleted from B. burgdorferi only after introduction of a promoterless bb0250 under the control of an inducible lac promoter, indicating that it is an essential gene in this organism. Growth of the mutant in the absence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside resulted in cell death, preceded by cell division defects characterized by elongated cells and membrane bulges, demonstrating that bb0250 is required for proper cell division and envelope integrity. Finally, we show that BB0250 depletion leads to imbalanced membrane phospholipid composition in borrelia. These results demonstrate a strong conservation of function of the dedA gene family across diverse species of Gram-negative bacteria and a requirement for this protein family for normal membrane lipid composition and cell division.

The dedA family is a highly conserved bacterial gene family encoding inner membrane proteins of unknown function (35). There are more than 2,000 homologs currently found in the NCBI protein database (protein BLAST score versus Escherichia coli DedA of <0.02), and many species of bacteria have multiple homologs. This built-in redundancy has precluded easy genetic analysis. Each of the dedA homologs in E. coli (yqjA, yghB, yabI, yohD, dedA, ydjX, ydjZ, and yqaA) is individually nonessential as the single gene knockouts have been made and are available in the Keio collection (1). Our group has determined that simultaneous deletion of yghB and yqjA from E. coli results in a strain (named BC202; ΔyghB::Kanr ΔyqjA::Tetr) that has abnormal membrane phospholipid composition, does not complete cell division (forming chains of cells), and fails to grow at 42°C (35). YghB and YqjA are proteins of 219 and 220 amino acids, respectively, displaying 61% amino acid identity. The other six E. coli homologs display roughly 25 to 30% amino acid identity with each other and YghB/YqjA.

The E. coli mutant BC202 referred to above displays several intriguing phenotypes that reflect important functions for the DedA family. The membrane and cell division defects of BC202 are present at both the permissive and nonpermissive growth temperatures. However, BC202 is not hypersensitive to antibiotics or detergents, likely signifying an intact outer membrane, under permissive growth conditions (35). We have demonstrated that the periplasmic amidases AmiA and AmiC are not exported to the periplasm in E. coli mutant BC202 (31). These amidases are normally exported across the inner membrane via the twin arginine transport (Tat) pathway in E. coli (6), a Sec-independent protein export pathway found in many bacteria and also present in archaea and plants (4, 5, 11, 26). AmiA and AmiC are required for normal cell division and envelope integrity (19). ΔTat mutants also display cell division defects due to loss of amidase export (6, 33). Overexpression of the components of the Tat pathway (TatABC) restores normal cell division and growth to BC202 (31). However, BC202 shares some, but not all, phenotypes with ΔTat and amidase mutants. In spite of this progress, a precise function for these genes remains to be determined.

We are interested in determining if the functions of dedA family genes are conserved in diverse bacterial species. The spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is a Gram-negative pathogen that is the cause of Lyme disease (3, 9, 34). B. burgdorferi has a complex enzootic life cycle where it cycles between tick and vertebrate hosts with unique patterns of gene expression to ensure survival in each host (20, 29). The B. burgdorferi genome has been sequenced and consists of one linear chromosome and 21 linear and circular plasmids (17). Notably, its genome possesses only one dedA family homolog, annotated bb0250, present on the linear chromosome. Since tools for the genetic manipulation of B. burgdorferi are available and because of the lack of genome redundancy of dedA genes in this organism, we sought to examine the function and essentiality of B. burgdorferi bb0250. Here, we show that cloned bb0250 can complement the mutant phenotypes of E. coli mutant BC202 and localizes to the inner membrane in E. coli. Furthermore, we have deleted bb0250 from B. burgdorferi, and we demonstrate that it is an essential gene in this organism. Loss of gene expression from an inducible plasmid results in cell division defects, morphological abnormalities, changes in membrane phospholipid composition, and growth arrest, implying a general role for DedA family membrane proteins in cell division and maintenance of proper membrane composition and function. Intriguingly, these phenotypes are independent of any role these proteins may play in the Tat protein export pathway since the B. burgdorferi genome does not encode homologs of TatABC or any proteins with predicted Tat-dependent signal peptides (12). These results demonstrate conserved and important functions for DedA family inner membrane proteins in bacterial cell physiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Tryptone and yeast extract were from Difco. Radioisotopes were purchased from Perkin Elmer. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. All other chemicals were reagent grade and purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or VWR. E. coli was grown in LB broth, and B. burgdorferi was grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly H (BSK-H) complete medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 33°C. Antibiotics gentamicin (50 μg/ml for B. burgdorferi; 5 μg/ml for E. coli), ampicillin ([Amp] 100 μg/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) were added to the growth medium as necessary.

Construction of pBB0250-GFP.

The gene bb0250 was amplified from B. burgdorferi B31 genomic DNA using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) with cloning primers 250F and 250R (sequences of all primers are given in Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR product was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA), digested with XbaI/BamHI, and cloned into a similarly treated vector, pET28 (Novagen). Subsequently, the gene along with its upstream ribosomal binding and N-terminal hexahistidine tag was amplified from pET-BB0250 using upstream primers 250GF and 250GR (see Table S2), digested with XbaI/XhoI, and ligated into a similarly digested pTB28 (6) following removal by gel purification of the original XbaI/XhoI fragment encoding AmiC. The resulting plasmid, pBB0250-GFP (where GFP is green fluorescent protein) expresses a fusion protein consisting of N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged BB0250 linked to the GFP variant GFPmut2 via the linker region LEDPPAEF. The control vector pBB0 encoding lac-inducible GFP was constructed by digesting vector pTB28 (6) with EcoRI, removing the 1.5-kb insert encoding AmiC by gel purification, and ligation to recircularize the plasmid. DNA sequencing conducted at the Louisiana State University (LSU) College of Basic Science Genomics Facility confirmed the sequences of all cloned PCR products used in this study.

Construction of p250KO.

A 4,566-bp fragment containing the entire bb0250 gene (615 bp) with flanking upstream (1,950 bp) and downstream (1,991 bp) sequence was amplified with Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) with primers P1F and P1R, which also contained linkers for Acc65I and NcoI, respectively (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), digested with the appropriate enzymes, and ligated into a similarly digested vector pNCO1T (30, 38), creating pNCO1T-250. A gentamicin cassette (aacC1), which confers gentamicin resistance in both E. coli and B. burgdorferi (16), was amplified from the shuttle vector pBSV2G (38) using primers P2F and P2R and digested with PstI/BspEI. Finally, pNCO1T-250 was amplified using primers P3F and P3R, similarly digested with PstI/BspEI, and ligated to the gentamicin resistance cassette. This procedure created a plasmid termed p250KO that cannot replicate in borrelia.

Construction of the pWTD250 inducible covering plasmid.

Following unsuccessful attempts to disrupt bb0250, we reasoned that this locus is essential in B. burgdorferi. Our strategy was to use the newly developed borrelia-optimized plasmids allowing for controllable gene expression using the well-characterized lac promoter/repressor (7). Michael Norgard (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) generously provided plasmid pJSB104. This plasmid is optimized for tight regulation of gene expression in Borrelia using the lac promoter. In the absence of convenient restriction sites, we used a semiblunt cloning approach. pJSB104 was amplified using primers P4F and P4R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The gene bb0250 was amplified using primers P5F and P5R. The PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA), digested with NcoI, and ligated. Ligation reaction products were transformed into competent XL1-Blue cells, and transformants were selected on LB-streptomycin plates. The resulting plasmid was named pWTD250.

Disruption of the bb0250 locus.

The clone 13A derived from B. burgdorferi B31 5A13 was used for this study because of its high transformability (38). The construct pWTD250 was electroporated into 13A in the presence of 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. Sixteen transformants were obtained and analyzed for plasmid content as described previously (39). All 13A transformants lost plasmid cp9 because the of incompatibility of cp9 with pWTD250. The transformants shared the same plasmid content as the 13A clone except for cp9 and were denoted CK (Table 1). To disrupt the bb0250 locus, as described previously (38), 10 μg of p250KO DNA was electroporated into CK spirochetes in the presence of 50 μg/ml of gentamicin and 5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cultures were maintained in 5 mM IPTG during all of the following manipulations. Gentamicin-resistant clones were screened as described previously (38); the insertion of the aacC1 cassette into the bb0250 locus was confirmed by PCR using primers P7F and P7R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) specific for the cassette and primers P6F and P6R, flanking the bb0250 gene (see Fig. 5).

TABLE 1.

Number of dedA family genes found in sequenced genomes of representative bacterial and archaeal species

| Strain | No. of DedA family homologsa |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli K-12 | 8 |

| Salmonella enterica SL480 | 6 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | 5 |

| Helicobacter pylori J99 | 2 |

| Vibrio cholerae El Tor N16961 | 3 |

| Caulobacter crescentus CB15 | 3 |

| Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 | 3 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi B31 | 1 |

| Bacillus subtilis 168 | 6 |

| Bacillus anthracis Ames | 8 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | 4 |

| Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW-3/CX | 0 |

| Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 | 3 |

| Halobacterium salinarum NRC-1 | 1 |

Significant homologs (protein BLAST E-value of <0.02) of E. coli YqjA, YghB, DedA, YohD, YabI, YdjZ, YdjX, and YqaA were included in the number of genes. Accession numbers for each gene are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Microscopy of E. coli and B. burgdorferi strains.

Localization of BB0250-GFP was done using live cells. BC202 harboring plasmid pBB0250-GFP was grown overnight in LB medium with 100 μg/ml Amp and was diluted 1:200 in 20 ml of fresh LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and 0.3 mM IPTG. The cells were grown at 30°C in an incubator with shaking at 225 rpm to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.4. Live cells were directly harvested from the growth medium by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh LB medium at an OD600 of ∼1.0. Ten microliters of the cells was applied to agarose-coated glass slides and observed using differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy. The images of B. burgdorferi were visualized and captured by using an Axio Imager (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

SEM.

The cultured cells were centrifuged, washed once with room temperature phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate-0.1 M sucrose buffer, pH 7.3. The mixture was drawn into a 10-ml syringe with a Swinney filter holder fitted with a 13-mm-diameter, 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filter. Filtered cells were fixed for 2 h and then rinsed five times in 0.02 M glycine in 0.1 M cacodylate-0.1 M sucrose buffer, pH 7.3, over a 12-h period. Samples were postfixed for 1 h with 2% osmium tetroxide, rinsed briefly in distilled H2O, en bloc stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate for 1 h in the dark, rinsed again in distilled H2O, and dehydrated with an ethanol series. The filter paper was removed from the syringe and cut in half for scanning electron microscopy (SEM), critical point dried with liquid CO2 in a Denton critical point dryer (CPD), mounted on aluminum SEM stubs, coated with gold-palladium (60:40) in an Edwards S150 sputter coater, and imaged with a JSM-6610 SEM.

Growth curve.

Strain DXL-01 was grown at 33°C to late log phase (approximately 108 cells/ml) in BSK-H medium containing 1 mM IPTG and then diluted to 104 cells/ml with BSK-H medium supplemented with either 0 or 1 mM IPTG. Cell numbers were determined twice a day for 12 days under dark-field microscopy.

Cell fractionation and Western blotting.

E. coli strain BC202 harboring plasmid pBB0 (expressing soluble GFP) or pBB0250-GFP was grown in LB-Amp in the presence of 0.3 mM IPTG to an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0. Cell pellets were lysed by sonication of spheroplasts prepared using lysozyme-EDTA as described previously (43). The crude lysate was centrifuged at 2,700 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells. Membrane and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared by centrifugation of cell lysates for 1 h at 100,000 × g in an ultracentrifuge. Following the first ultracentrifugation, the pellet (membrane fraction) was resuspended in 10 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.8, and 25% sucrose using a Dounce homogenizer. The supernatants (cytoplasmic fractions) and resuspended pellets were then centrifuged in separate tubes for an additional 1 h at 100,000 × g. Total protein was determined on the cytoplasm and resuspended membranes using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce), and equal amounts of protein were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (13) using the anti-GFP primary antibody JL-8 (Clontech). The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Thermo Scientific), and detection was performed with an Immun-Star kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). E. coli inner and outer membranes were separated by 30 to 60% isopycnic sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation as described previously (13). NADH oxidase activity (an inner membrane marker) was measured spectrophotometrically (28). Equal volumes of each fraction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using antibodies against OmpA (an outer membrane marker) or GFP.

Phospholipid analysis.

E. coli strains were grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 1.0 in LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and 0.3 or 1.0 mM IPTG. Cells were diluted 1:3 into identical fresh LB medium prewarmed to 44°C and grown in a shaking water bath for 30 min. 32Pi was added to a concentration of 4 μCi/ml, and growth was continued for 15 min. B. burgdorferi strains were grown in BSK-H complete medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and 0, 1.0, or 5.0 mM IPTG at 33°C to mid-log phase. 32Pi was added to a concentration of 4 μCi/ml, and growth was continued for 4 h. Following growth and labeling, both E. coli and B. burgdorferi cells were extracted and analyzed in an identical manner. Cells were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min, and pellets were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, and suspended in 0.2 ml of PBS. Chloroform and methanol were added to cells to a final ratio of chloroform-methanol-PBS of 1:2:0.8. The extraction mixture was allowed to incubate for 1 h at room temperature with occasional mixing. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge for 10 min at 20,000 × g at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and chloroform and water were added to adjust the ratio of chloroform-methanol-water to 1:1:0.8, resulting in a two-phase mixture. The aqueous upper phase was discarded, and the lower phase was washed with fresh preequilibrated upper phase. Lipid species were resolved by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on Silica gel 60 plates (Merck) using the solvent chloroform-methanol-glacial acetic acid (13:5:2) and analyzed using a Phosphorimager equipped with IQMac software.

RESULTS

bb0250 is the only member of the dedA family in B. burgdorferi.

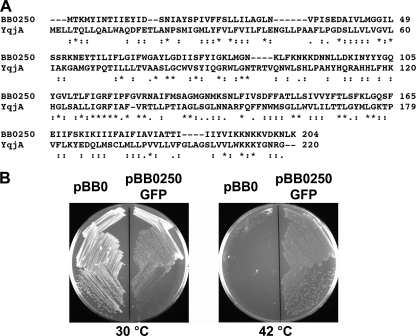

The dedA family is a highly conserved bacterial gene family, and many species, including E. coli, have multiple homologs (Table 1), suggesting an important function(s) for this family. Our recent work demonstrates important but redundant functions for yghB and yqjA, two dedA genes, in E. coli physiology (31, 35). BC202 (W3110 ΔyqjA::Tetr ΔyghB::Kanr) is temperature sensitive for growth, has altered membrane lipid composition, and displays cell division defects, forming chains of incompletely divided cells (35). However, the presence of multiple homologs with potentially redundant functions capable of compensating for each other complicates genetic investigation into functions of this protein family in E. coli. B. burgdorferi possesses only one putative dedA gene (Table 1). This gene is annotated bb0250 and encodes a protein with only 19% identity and 56% similarity to E. coli YqjA across the entire length of the protein (Fig. 1A). To experimentally examine whether bb0250 belongs to the dedA family, bb0250 was amplified from B. burgdorferi genomic DNA and cloned in frame with a C-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) to allow for simultaneous detection by Western blotting and analysis with fluorescence microscopy. This plasmid, pBB0250-GFP (Table 2) was transformed into BC202, and the resulting strain was grown at 30 and 42°C on LB medium containing ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG. pBB0250-GFP is capable of supporting growth of BC202 at 42°C (Fig. 1B), suggesting that BB0250 can functionally substitute for the absence of YghB and YqjA in the E. coli mutant BC202.

FIG. 1.

The Borrelia genome encodes a protein with 19% amino acid identity to E. coli YqjA that supports growth of BC202 (ΔyghB::Kanr ΔyqjA::Tetr) at 42°C. (A) Alignment of E. coli YqjA and B. burgdorferi BB0250. The two proteins display 19% identity (56% similarity) over their entire lengths. The alignment was performed using Clustal W (24). E. coli YghB displays 19% identity and 50% similarity to BB0250 (alignment not shown). (B) Cloned BB0250-GFP can restore growth to BC202 at 42°C. bb0250 was amplified from B. burgdorferi genomic DNA. The gene was cloned into a vector in frame with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and C-terminal green fluorescent protein and expressed in BC202. Ampr colonies of BC202 harboring control vector pBB0 or pBB0250-GFP were streaked onto LB-Amp plates containing 1 mM IPTG and incubated at 30 and 42°C overnight.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| W3110 | Wild type; F− λ− | E. coli genetic stock center, Yale University |

| BC202 | W3110 ΔyqjA::Tetr ΔyghB781::Kanr | 35 |

| B. burgdorferi | ||

| 13A | B. burgdorferi B31 5A13 subculture with high transformability and lacking plasmids lp25 and lp56 | 38 |

| CK | 13A harboring pWTD250 | This study |

| DXL-01 | 13A harboring Δbb0250::Genr(pWTD250) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28b | Expression vector, T7 lac promoter; Kanr | Novagen |

| pWTD52 | pWSK29 expressing YqjA-GFPmut2 fusion; Ampr | 31 |

| pET-BB0250 | BB0250 cloned into NdeI/BamHI sites of pET28 | This work |

| pTB28 | AmiC-GFP expression vector; Ampr | 6 |

| pBB0 | GFP expression vector, based on pTB28; Ampr | This work |

| pBB0250-GFP | BB0250-GFP expression vector; pTB28 with bb0250 cloned into XbAI/XhoI sites (following removal of amiC); Ampr | This work |

| PNCO1T | TA cloning vector | 14, 30 |

| pNCO1T-250 | pNCO1T with cloned 4,566-bp fragment (see Materials and Methods); Acc65I and NcoI linkers | This work |

| pBSV2G | Shuttle vector; Genr (aacC1) | 38 |

| p250KO | pNCO1T-250 with bb0250 replaced with Genr cassette from pBSV2G | This work |

| pJSB104 | pJD7::PpQE30-Bbluc and PflaB-BblacI (tandem); Specr/Strepr | 7 |

| pWTD250 | pJSB104 engineered to express bb0250 under the control of borrelia-optimized lac promoter | This work |

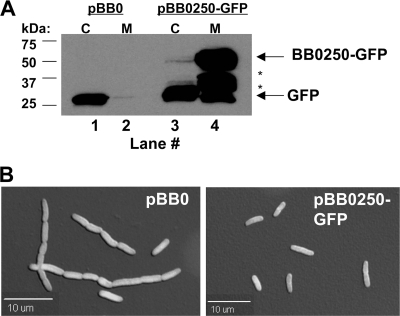

To localize BB0250 in E. coli, cytoplasmic and membrane fractions were prepared from BC202 expressing soluble GFP or BB0250-GFP. Soluble GFP localizes almost exclusively to the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, greater than 99% of BB0250-GFP localizes to the membrane fraction (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). Some presumed degradation products corresponding to the size of GFP can be found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A, lane 3), and this likely is responsible for the fluorescence that is seen throughout these cells in micrograph images (Fig. 2B). Fluorescent micrographs of BC202 expressing BB0250-GFP show that the plasmid corrects the cell division defect of BC202 under these conditions (Fig. 2B, right) while expression of soluble GFP does not (Fig. 2B, left). However, fluorescence appears throughout the cells during growth with all concentrations of IPTG that were tested (Fig. 2B, right), in contrast to the clear peripheral membrane fluorescence that is observed in these cells with GFP-tagged YqjA or YghB (31). This is likely due to the observed proteolysis of the fusion protein during expression in E. coli (Fig. 2A) and is not due to inefficient membrane targeting of the protein in E. coli.

FIG. 2.

BB0250-GFP expressed in BC202 localizes to the membrane fraction and corrects the cell division defect of BC202. (A) BC202 transformed with pBB0 expressing soluble GFP or pBB0250-GFP was grown in the presence of 0.3 mM IPTG. Cytoplasmic (C) and membrane (M) fractions were isolated and analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody against GFP. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. Arrows indicate the molecular masses corresponding to GFP and BB0250-GFP, and asterisks indicate the presence of presumed BB0250-GFP degradation products. (B) Fluorescent/DIC overlay images are shown for BC202 cells harboring plasmids pBB0 and pBB0250-GFP grown at 30°C in the presence of 0.3 mM IPTG.

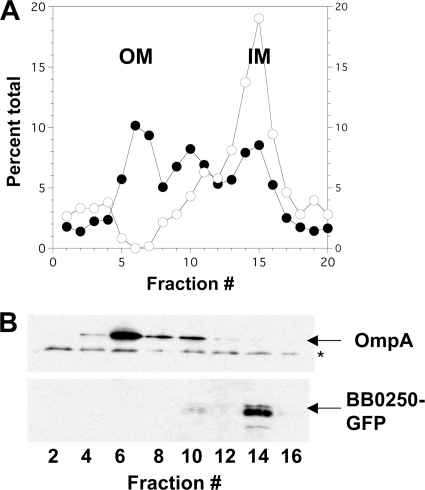

BB0250-GFP was localized to the inner membrane in E. coli using an isopycnic sucrose gradient to separate inner and outer membranes. Protein determination of individual fractions shows a total of three peaks, with inner membrane NADH oxidase activity centered on fraction 14 (Fig. 3A) and outer membrane OmpA centered on fraction 6 (Fig. 3B, top panel). The middle peak, commonly observed in these preparations, may represent fused inner-outer membranes caused by artifactual membrane mixing (13). BB0250-GFP colocalizes with NADH oxidase activity near fraction 14, demonstrating that the protein localizes to the inner membrane when expressed in E. coli (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). These data show conclusively that the fusion protein is correctly targeted to the inner membrane and restores normal cell division, and they demonstrate that BB0250 can functionally substitute for the absence of YghB and YqjA in E. coli mutant BC202, thus confirming that it is a member of the dedA family. While these results do not directly address the localization of the BB0250 protein in borrelia cells, we feel that it is reasonable to assume that it is also an inner membrane protein when expressed in its native cell type.

FIG. 3.

BB0250-GFP expressed in BC202 localizes to the inner membrane. (A) BC202 transformed with pBB0250-GFP was grown under Amp selection in the presence of 1 mM IPTG; total membranes were isolated, and inner and outer membranes (IM and OM, respectively) were separated with a sucrose gradient. Twenty fractions were recovered from the gradient. Total protein (filled circles) and NADH oxidase activity (open circles) were measured on each gradient fraction, and values are expressed as percent total across the gradient. (B) Antibodies against OmpA were used to identify outer membrane fractions, and antibodies against GFP were used to identify fractions containing BB0250-GFP. Equal volumes of sucrose gradient fractions were loaded in each lane. The band marked with an asterisk on the OmpA blot is a nonspecific band that serves as a loading control.

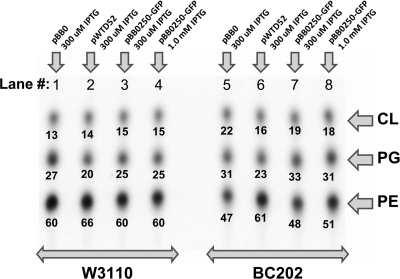

BC202 also displays an intriguing membrane phospholipid imbalance (35). Whether grown at 30 or 42°C, BC202 has reduced levels of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and increased levels of both phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and cardiolipin (CL). Normal lipid levels can be restored by expression of a cloned copy of yghB or yqjA. It is not yet clear if these membrane lipid changes are directly related to the growth and cell division phenotypes observed in BC202. We were therefore interested in determining if expression of bb0250 could restore normal lipid levels in BC202, with the caveat being that B. burgdorferi does not synthesize PE and instead produces membrane lipids phosphatidylcholine (PC) and PG (see Discussion). E. coli W3110 and BC202 harboring appropriate plasmids were grown, and phospholipids were labeled, extracted, and analyzed as previously described (35). W3110 produces nearly identical membrane lipid composition regardless of whether the cells express GFP, YqjA-GFP, or BB0250-GFP (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 4), with 60 to 66% of the lipids in the form of PE, 20 to 27% in the form of PG, and 13 to 15% as CL. In contrast, BC202 expressing GFP produces somewhat lower levels of PE (47% of total), with the remaining lipids in the form of PG and CL (Fig. 4, lane 5). Expression of YqjA-GFP by BC202 restores lipid composition to near what is found in parent strain W3110 (Fig. 4, lane 6). However, expression of bb0250 has essentially no effect on lipid levels in BC202 (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 8) even though the expression of the gene can restore growth (Fig. 1B) and cell division (Fig. 2B). In spite of this lack of an effect on lipid composition of E. coli, we show below that depletion of BB0250 from B. burgdorferi has marked effects upon lipid composition in its native species (see Fig. 8).

FIG. 4.

Expression of BB0250 does not correct lipid imbalance in E. coli strain BC202. W3110 and BC202 were transformed with vector pBB0, pWTD52, or pBB0250-GFP, as indicated, expressing GFP, YqjA-GFP, or BB0250-GFP, respectively. Cells were grown in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics and 0.3 M (lanes 1 to 3 and 5 to 7) or 1 mM (lanes 4 and 8) IPTG for 3 h at 30°C to an OD600 of ∼1.0 and then diluted 1:3 into fresh medium prewarmed to 42°C; cells were grown for an additional 30 min and labeled for 15 min with 32Pi. Phospholipids were extracted, resolved with thin-layer chromatography, and analyzed with a Phosphorimager. The number below each spot gives the percent contribution of each lipid species to the total phospholipid composition for each strain. This is a representative experiment, with the numbers corresponding to the data shown. Nearly identical data were obtained on three separate occasions.

bb0250 is required for cell division in borrelia.

We repeatedly attempted to replace the bb0250 locus in B. burgdorferi B31 with a gentamicin resistance cassette using established methods (37, 38). Unfortunately, no gentamicin-resistant clones were isolated that did not harbor an amplifiable copy of bb0250 (data not shown). We reasoned that bb0250 is an essential gene in this organism. Norgard and colleagues described a plasmid system for inducible gene expression optimized for B. burgdorferi based on the lac promoter/repressor system (7). We placed a promoterless bb0250 under the control of the borrelia-optimized lac promoter using plasmid pJSB104 (Table 2) as a template. The plasmid also expresses a borrelia-optimized lacI gene as well as a gene encoding resistance to streptomycin/spectinomycin (7). This plasmid, here named pWTD250, is maintained in E. coli and could restore growth to BC202 at 42°C in the presence or absence of IPTG, indicating the lack of tight control of gene expression in the E. coli host (data not shown).

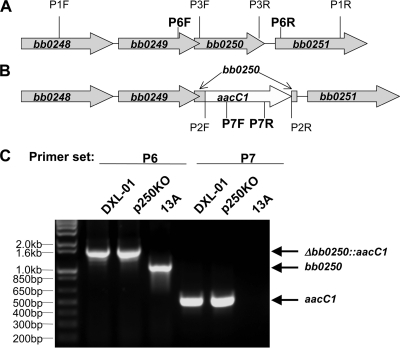

pWTD250 was transformed into B. burgdorferi B31, and transformants were maintained in the presence of streptomycin. Disruption of bb0250 was repeated, and a single clone was isolated that was resistant to gentamicin and did not contain a chromosomally encoded amplifiable bb0250 gene (Fig. 5A and B). This clone was named DXL-01 [Δbb0250::Genr(pWTD250)] (Table 2) and was maintained in medium containing streptomycin and 1 or 5 mM IPTG. We did not observe any differences in growth at levels of IPTG greater than 1 mM (data not shown). We confirmed the deletion of bb0250 with PCR amplification using primers specific for the gentamicin cassette and primers specific for the region flanking the gene itself (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Disruption of bb0250 in B. burgdorferi B31 harboring pWTD250. (A) A diagram of the bb0250 locus and adjacent open reading frames. The bb0250 gene is located on the borrelia linear chromosome downstream from bb0248 (annotated oligoendopeptidase F [17]; 1,773 bp) and bb0249 (phosphatidylcholine synthase [17, 36]; 705 bp) and upstream of bb0251 (leucyl-tRNA synthase [17]; 2,523 bp). The binding sites of primers P1F, P1R, P3F, P3R, P6F, and P6R are indicated, with P6 primers, used the experiment shown in panel C, in bold print. Genes are not drawn to scale. (B) A diagram of the disrupted bb0250 locus showing the insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette (aacC1). The binding sites of primers P2F, P2R, P7F, and P7R are also shown, with P7 primers, used the experiment shown in panel C, in bold. The gentamicin resistance cassette inserts in such a way as to leave the first 39 bp and last 15 bp of the original bb0250 locus intact. (C) One gentamicin-resistant clone was screened, as described previously (38), for the insertion of the aacC1 gentamicin resistance cassette into the bb0250 locus. Cassette insertion and gene deletion were confirmed by PCR using primers P6F and P6R, flanking the BB0250 gene (second to fourth lanes) and primers P7F and P7R specific for the cassette (fifth to seventh lanes) with template DNA from strain DXL-01, plasmid pWTD250KO, and strain 13A, as indicated. Sequences of all primers are given in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

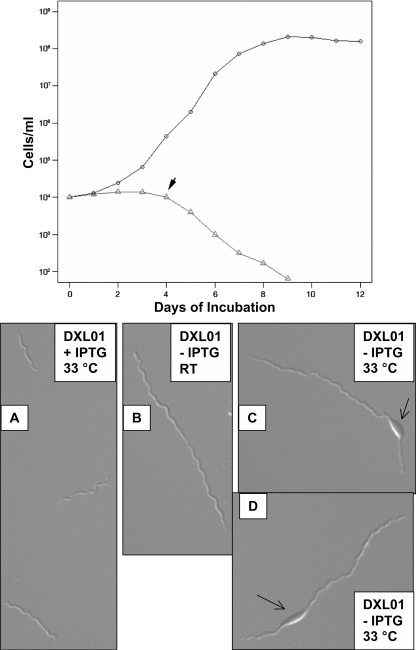

The growth of DXL-01 in the presence or absence of IPTG was measured. DXL-01 was cultured in 1 mM IPTG until the cells reached late log phase (approximately 108 cells/ml). Cells were then diluted to 104 cells/ml into medium containing 0 or 1 mM IPTG, and cell numbers were determined twice a day. As seen in Fig. 6 (top panel), the growth rate of cells grown in the absence of IPTG begins to slow by day 2, and cells begin to lose viability after day 4, as indicated by the steep drop in total cell numbers after this time point. Cells grown in the presence of IPTG continued to grow normally until late log phase was reached (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

B. burgdorferi Δbb0250 mutant displays cell division defects under nonpermissive growth conditions. (Upper panel) B. burgdorferi DXL-01 was cultured in BSK-H medium supplemented with either 1 mM (circles) or 0 mM (triangles) IPTG and appropriate antibiotics. The arrow indicates the time point when cells started to bulge and then die. (Lower panels) DXL-01 was grown in BSK-H medium and appropriate antibiotics supplemented with 5 mM IPTG (+IPTG) or without (−) IPTG for 4 to 5 days at room temperature RT; ∼25°C) or at 33°C. Membrane bulging (arrows) was more evident at 33°C but was also observed at 25°C. The images of the spirochetes were visualized and captured by using an Axio Imager (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

Cells were examined using microscopy after 4 days of growth in the presence or absence of IPTG. DXL-01 was grown in the presence of 0, 1, and 5 mM IPTG, and the cells were visualized using an Axio Imager. Growth in 1 or 5 mM IPTG resulted in cells that grew and looked identical to the parent strain under the same conditions (Fig. 6A). The mutant did not grow in 0 mM IPTG for longer than 5 days. However, when the cells were grown without IPTG for several days, they appeared elongated and formed filaments extending in length up to seven times what is normally observed (Fig. 6B). In addition, growth in the absence of IPTG resulted in the appearance of membrane bulging and protrusions (Fig. 6C and D). During growth in the absence of IPTG, all mutant cells eventually formed bulges before death. Similar membrane bulging is seen in bacteria treated with cell wall-targeting antibiotics (8, 10) and is frequently observed in the E. coli mutant BC202 (35), suggesting that DedA family proteins play a pivotal role in envelope maintenance.

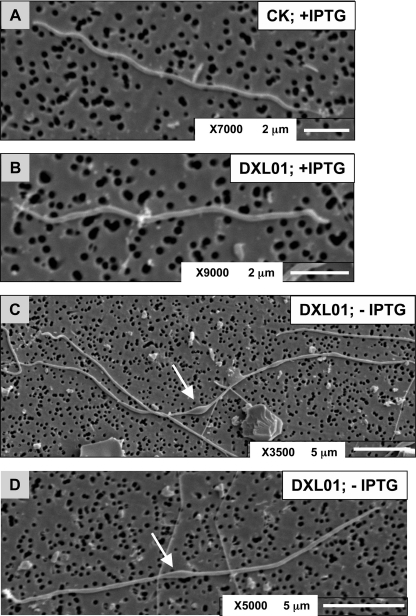

The mutant was also analyzed at high resolution using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The parent strain and the mutant grown in the presence of IPTG appeared normal and possessed typical lengths and morphologies (Fig. 7A and B). However, DXL-01 grown in the absence of IPTG appeared elongated with signs of membrane bulging (Fig. 7C and D). The mutant cells appear less spiral-shaped than those of the parent strain, but this can be due to changes in the flagellum structure associated with the increase in cell length. A similar shape is seen in a chaining borrelia amidase mutant (40).

FIG. 7.

Scanning electron micrographs of B. burgdorferi strains. Parent strain CK and strain DXL-01 were cultured for 4 to 5 days in the presence of 5 mM IPTG (+IPTG) or without (−) IPTG in BSK-H medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. The arrows indicate signs of membrane bulging in DXL-01. Cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and imaged with a JSM-6610 scanning electron microscope.

In contrast to BC202 (35), there is no sign of formation of division septa in the borrelia dedA mutant (Fig. 6 and 7). This is consistent with the severity of the phenotype observed here (lethality) versus the “milder” phenotype observed for BC202 (temperature sensitivity), possibly due to functional redundancy of other dedA genes in E. coli. These results collectively demonstrate that bb0250 is an essential gene in B. burgdorferi, and depletion of protein levels by growth in the absence of IPTG results in marked defects in cell division and cell envelope function.

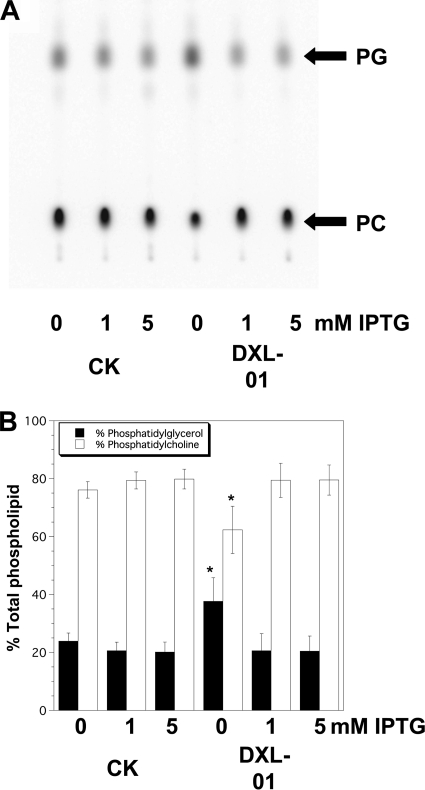

bb0250 is required to maintain normal membrane lipid composition in B burgdorferi.

The borrelia mutant reported here is reminiscent of the E. coli mutant BC202 (ΔyqjA::Tetr ΔyghB::Kanr) that also displays cell division defects (31, 35). BC202 also has an altered membrane phospholipid composition, with decreased levels of the zwitterionic phospholipid PE (Fig. 4) (∼40 to 45% of total phospholipids versus ∼65 to 70% normally) and increased levels of the acidic phospholipids PG and CL (Fig. 4) (∼55 to 60% versus ∼30 to 35% normally) (35). Even though expression of bb0250 was not capable of restoring wild-type lipid composition to BC202 (Fig. 4), we were interested in determining the effect of titration of gene expression on lipid composition of borrelia membranes. We measured the membrane phospholipid composition of the B. burgdorferi parent 13A and the DXL-01 mutant by labeling cells that had been cultured for 4 to 5 days in the presence or absence of the inducing agent IPTG. Strains were grown at 33°C in the presence of 0, 1, or 5 mM IPTG; the cells were labeled with 32Pi for 4 h, and lipids were extracted and resolved using TLC; radioactivity was imaged and quantified using a Phosphorimager. B. burgdorferi synthesizes only two membrane phospholipids, the zwitterionic lipid phosphatidylcholine (PC) and the acidic lipid PG (2). Newly synthesized phospholipids in the parent strain CK were composed of approximately 80% PC and 20% PG, regardless of IPTG concentration (Fig. 8, first three lanes of each panel). When DXL-01 is grown in the presence of 1 or 5 mM IPTG, the membranes have similar compositions, with about 80% of the total phospholipids in the form of PC (Fig. 8, fifth and sixth lanes of each panel). However, when the mutant strain is grown in the absence of IPTG to deplete the cells of BB0250 protein, the membrane composition changes so that roughly 40% of the phospholipids are PG and 60% are PC (Fig. 8, fourth lanes). Phospholipid labeling efficiency in the mutant is similar to that of the parent strain, indicating that the cells are metabolically active so toxicity or cell death is not a significant problem under these growth conditions. While these numbers fall just short of statistical significance at a P value of <0.1 using Student's t test, it is also likely that the plasmid-encoded protein was not completely diluted away under these growth conditions. This result suggests that loss of the bb0250 gene product results in cells with an abnormal membrane phospholipid composition that can be restored by titration of gene expression using IPTG. The fact that the plasmid copy of bb0250 restores normal membrane composition also demonstrates that the Δbb0250::Genr mutation in DXL-01 does not disrupt function of the gene immediately upstream, bb0249, encoding phosphatidylcholine synthase (Fig. 5A) (36). Collectively, these data demonstrate a requirement for the dedA homolog of B. burgdorferi for normal cell division and maintenance of normal membrane lipid composition.

FIG. 8.

Altered B. burgdorferi membrane phospholipid composition upon depletion of BB0250 protein. B. burgdorferi strains CK and DXL-01 [Δbb0250::Genr(pWTD250)] (Table 2) were grown in BSK-H medium supplemented with 0, 1, or 5 mM IPTG for 4 to 5 days at 33°C. 32Pi was added, and growth was continued for 4 h. Cells were harvested and washed, and phospholipids were extracted and resolved using thin-layer chromatography. Radioactivity was detected with a Phosphorimager. A representative image is presented in panel A showing migration of the two major phospholipids, PC and PG. (B) Quantification of percent contribution of each phospholipid species to the total phospholipid signal. Results represent average and standard deviations of three separate determinations. *, P < 0.1, using a Student's t test comparing results of DXL-01 with those of CK for the 0 mM IPTG concentration.

DISCUSSION

The dedA gene family is found in nearly all bacterial species, and distant homologs are found in sequenced eukaryotic genomes including Caenorhabditis elegans (41), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (21), and mammals. The function has not been established for any dedA family gene in any organism. Analysis of individual bacterial genomes also shows evidence of substantial gene duplication. E. coli, for example, possesses up to eight dedA family genes, and many species have at least two such genes (Table 1). However, simultaneous deletion of yqjA and yghB, encoding E. coli dedA family members with 61% amino acid identity, results in temperature sensitivity, membrane defects, and interruption of normal cell division (35). Such functional redundancy may therefore be expected as this family is analyzed in other species of bacteria. B. burgdorferi possesses only one member of the dedA gene family. This gene is annotated bb0250 and shows highest amino acid identity to E. coli YabI (25% identity) and DedA (25%), with 17 to 21% identity to the other E. coli DedA family members (YqjA, YghB, YohD, YdjX, YdjZ, and YqaA). B. burgdorferi is the cause of Lyme disease (3, 9, 34), and there is an ever-expanding set of genetic tools available to study functions of individual genes (29). This allowed us the opportunity to investigate the function of a dedA family gene in an organism free from homologs with possibly redundant functions.

Cloned bb0250 could restore growth at 42°C (Fig. 1B) and normal cell division (Fig. 2B) to BC202, an E. coli mutant with deletions of both yqjA and yghB (35). BB0250 also localized correctly to the inner membrane of E. coli when expressed in BC202 (Fig. 3) but was unable to restore normal lipid composition to BC202 (Fig. 4). These results demonstrate a strong conservation of function of DedA family proteins among distantly related species of Gram-negative bacteria.

Our initial attempts to disrupt the bb0250 locus using approaches described previously were unsuccessful, leading us to speculate that bb0250 may be required for viability of B. burgdorferi. bb0250 was cloned behind a borrelia-optimized lac promoter using the system developed by Norgard and colleagues (7). The presence of this plasmid allowed us to disrupt bb0250 and investigate of the effects of loss of gene expression on cellular physiology. The observation that cells do not grow in the absence of the inducing agent IPTG confirmed that bb0250 is indeed an essential gene in Borrelia. When DXL-01 [Δbb0250::Genr(pWTD250)] cells are cultured for a few days in the absence of IPTG, they stop growing and display an intriguing cell division phenotype with evidence of filamentation and membrane bulges (Fig. 6 and 7). This phenotype recalls that of BC202 (ΔyqjA::Tetr ΔyghB::Kanr), which forms chains of cells at the permissive growth temperature (35), and suggests that the distantly related dedA orthologs from E. coli and B. burgdorferi may carry out similar functions in their respective organisms. Similar phenotypes have been observed with E. coli treated with subinhibitory concentrations of cell wall-targeting antibiotics of the cephalosporin (8) and β-lactam classes (10), suggesting that the dedA family may be required for cell wall maintenance or function.

Both DXL-01 (Fig. 8) and BC202 (35) display alterations in membrane phospholipid composition. While E. coli and many bacteria synthesize three major phospholipids, PG, CL, and PE, B. burgdorferi synthesizes only two major membrane phospholipids, PG and PC (2, 36). PC is a major phospholipid in eukaryotic cells and is a membrane component of roughly 10% of bacterial species, including some photosynthetic bacteria and both symbionts and pathogens of eukaryotes (32, 42). Examination of the borrelia genome suggests that both PG and PC are synthesized using the precursor CDP-diacylglycerol. Borrelia PG is most likely synthesized as it is in E. coli via condensation of glycerol-3-phosphate with CDP-diacylglycerol by the enzyme PgsA, followed by dephosphorylation by PgpA (32). PC is synthesized in Borrelia by the direct condensation of choline (probably obtained from the host) with CDP-diacylglycerol, using the enzyme phosphatidylcholine synthase (BB0249) and not via N-methylation of PE as no gene encoding a PE N-methyltransferase (pmtA) is found within the borrelia genome (17, 32), nor is PE found in borrelia membranes (2).

PG is an acidic or negatively charged phospholipid while both PC and PE are zwitterionic lipids possessing both a positive and negative charge on the lipid headgroups. While there are significant chemical differences between PE and PC, the most important being that PC prefers to form bilayers while PE prefers the reverse hexagonal phase (HII) (reviewed in reference 25), they may function similarly in maintaining certain membrane properties due to their charge similarities. The fact that BC202 is depleted of PE while DXL-01 is depleted of PC perhaps suggests that one function of the DedA family proteins may be to sense membrane phospholipid composition and ensure a proper balance of zwitterionic and acidic phospholipids. However, to date there is no evidence of direct binding of any specific lipid to any DedA family protein. Since expression of BB0250 can restore cell division to BC202 (Fig. 2B) but not normal lipid composition (Fig. 4), it appears that these two phenotypes may be not causally related.

We have recently reported that BC202 fails to export the critical periplasmic amidases AmiA and AmiC to the periplasm, causing the cell division defect (31). AmiC, as well as AmiA, is exported from the cytoplasm via the twin arginine transport (Tat) pathway in E. coli (6). Like BC202, E. coli ΔTat mutants display cell division defects (33). However, Tat mutants display additional outer membrane defects that are not shared with BC202 (22, 33). It is not clear if the malfunction of the Tat pathway in BC202 is due directly to a role that YghB/YqjA play in the export pathway itself or to a secondary effect resulting from the disruption of proper membrane lipid composition. Importantly, the borrelia genome does not encode a homolog of TatA, TatB, or TatC or any predicted gene product containing a Tat-specific signal peptide (12). Therefore, it is still unclear what role DedA family proteins play in cell division and protein export, but the similarities between BC202 and the B. burgdorferi mutant described here are striking. One intriguing possibility that remains to be explored is that perhaps BB0250 somehow substitutes for a functional Tat pathway in B. burgdorferi.

Cell division of Borrelia has not been studied extensively, but the B. burgdorferi B31 genome contains homologs of several E. coli cell division proteins including FtsZ, FtsI, FtsW, FtsA, and FtsK (17). Amidase deletion mutants display cell-chaining phenotypes in both B. burgdorferi (40) and E. coli (18, 19). Cell division in Borrelia is dependent upon the presence of periplasmic flagella since mutants that lack the gene flaB display abnormal division (27). A since-retracted paper reported the requirement of borrelia FtsZ for proper cell division (15). Using cryoelectron tomography, cytoplasmic structures resembling FtsZ filaments and sites of midcell constriction are visible in Borrelia family spirochetes (23). These observations collectively suggest that cell division in borrelia functions similarly to cell division in other organisms.

The finding that a distantly related dedA family gene from B. burgdorferi can restore growth to BC202, an E. coli dedA family mutant that displays temperature sensitivity and impaired cell division, implies widespread and common functions for members of this gene family. Depletion of the gene product from a B. burgdorferi mutant causes abnormal cell division and membrane composition abnormalities that are reminiscent of those seen in BC202. Since dedA family genes are found in nearly all sequenced bacterial genomes and many sequenced environmental samples, this work establishes common functions for members of this family across diverse bacterial phyla. Future studies will be directed at identifying specific targets and functions of this interesting and widely distributed membrane protein family.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Norgard for providing plasmid pJSB104 and Thomas Bernhardt for providing plasmid pTB28. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions to improve the manuscript.

Financial support has been provided by the National Science Foundation (grant MCB-0841853 to W.T.D.), the Louisiana Board of Regents [LEQSF grant (200508)-RD-A-04 to W.T.D], the LSU Faculty Research Grant Program (to W.T.D), and the National Institutes of Health (grants AR053338 and AI077733 to F.T.L.). F.T.L. is the recipient of an Arthritis Foundation Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 September 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T., T. Ara, M. Hasegawa, Y. Takai, Y. Okumura, M. Baba, K. A. Datsenko, M. Tomita, B. L. Wanner, and H. Mori. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belisle, J. T., M. E. Brandt, J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard. 1994. Fatty acids of Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 176:2151-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benach, J. L., E. M. Bosler, J. P. Hanrahan, J. L. Coleman, G. S. Habicht, T. F. Bast, D. J. Cameron, J. L. Ziegler, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, R. Edelman, and R. A. Kaslow. 1983. Spirochetes isolated from the blood of two patients with Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:740-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berks, B. C., T. Palmer, and F. Sargent. 2005. Protein targeting by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:174-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks, B. C., F. Sargent, and T. Palmer. 2000. The Tat protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35:260-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernhardt, T. G., and P. A. de Boer. 2003. The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1171-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blevins, J. S., A. T. Revel, A. H. Smith, G. N. Bachlani, and M. V. Norgard. 2007. Adaptation of a luciferase gene reporter and lac expression system to Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1501-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braga, P. C., M. Dal Sasso, and S. Maci. 1997. Cefodizime: effects of sub-inhibitory concentrations on adhesiveness and bacterial morphology of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli: comparison with cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgdorfer, W., A. G. Barbour, S. F. Hayes, J. L. Benach, E. Grunwaldt, and J. P. Davis. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalhoff, A., T. Nasu, and K. Okamoto. 2003. Target affinities of faropenem to and its impact on the morphology of Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Chemotherapy 49:172-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Buck, E., E. Lammertyn, and J. Anne. 2008. The importance of the twin-arginine translocation pathway for bacterial virulence. Trends Microbiol. 16:442-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilks, K., R. W. Rose, E. Hartmann, and M. Pohlschroder. 2003. Prokaryotic utilization of the twin-arginine translocation pathway: a genomic survey. J. Bacteriol. 185:1478-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doerrler, W. T., and C. R. H. Raetz. 2005. Loss of outer membrane proteins without inhibition of lipid export in an Escherichia coli YaeT mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27679-27687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downie, A. B., L. M. Dirk, Q. Xu, J. Drake, D. Zhang, M. Dutt, A. Butterfield, R. R. Geneve, J. W. Corum III, K. G. Lindstrom, and J. C. Snyder. 2004. A physical, enzymatic, and genetic characterization of perturbations in the seeds of the brownseed tomato mutants. J. Exp. Bot. 55:961-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubytska, L., H. P. Godfrey, and F. C. Cabello. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi ftsZ plays a role in cell division. J. Bacteriol. 188:1969-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Elias, A. F., J. L. Bono, J. J. Kupko III, P. E. Stewart, J. G. Krum, and P. A. Rosa. 2003. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, O. White, K. A. Ketchum, R. Dodson, E. K. Hickey, M. Gwinn, B. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, R. D. Fleischmann, D. Richardson, J. Peterson, A. R. Kerlavage, J. Quackenbush, S. Salzberg, M. Hanson, R. van Vugt, N. Palmer, M. D. Adams, J. Gocayne, J. Weidman, T. Utterback, L. Watthey, L. McDonald, P. Artiach, C. Bowman, S. Garland, C. Fuji, M. D. Cotton, K. Horst, K. Roberts, B. Hatch, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidrich, C., M. F. Templin, A. Ursinus, M. Merdanovic, J. Berger, H. Schwarz, M. A. de Pedro, and J. V. Holtje. 2001. Involvement of N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidases in cell separation and antibiotic-induced autolysis of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidrich, C., A. Ursinus, J. Berger, H. Schwarz, and J. V. Holtje. 2002. Effects of multiple deletions of murein hydrolases on viability, septum cleavage, and sensitivity to large toxic molecules in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:6093-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovius, J. W., A. P. van Dam, and E. Fikrig. 2007. Tick-host-pathogen interactions in Lyme borreliosis. Trends Parasitol. 23:434-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inadome, H., Y. Noda, Y. Kamimura, H. Adachi, and K. Yoda. 2007. Tvp38, Tvp23, Tvp18 and Tvp15: novel membrane proteins in the Tlg2-containing Golgi/endosome compartments of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Exp. Cell Res. 313:688-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ize, B., N. R. Stanley, G. Buchanan, and T. Palmer. 2003. Role of the Escherichia coli Tat pathway in outer membrane integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1183-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kudryashev, M., M. Cyrklaff, W. Baumeister, M. M. Simon, R. Wallich, and F. Frischknecht. 2009. Comparative cryo-electron tomography of pathogenic Lyme disease spirochetes. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1415-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin, M. A., G. Blackshields, N. P. Brown, R. Chenna, P. A. McGettigan, H. McWilliam, F. Valentin, I. M. Wallace, A. Wilm, R. Lopez, J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, A. G. 2004. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666:62-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, P. A., D. Tullman-Ercek, and G. Georgiou. 2006. The bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motaleb, M. A., L. Corum, J. L. Bono, A. F. Elias, P. Rosa, D. S. Samuels, and N. W. Charon. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10899-10904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osborn, M. J., J. E. Gander, E. Parisi, and J. Carson. 1972. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 247:3962-3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosa, P. A., K. Tilly, and P. E. Stewart. 2005. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:129-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi, Y., Q. Xu, S. V. Seemanapalli, K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2006. The dbpBA locus of Borrelia burgdorferi is not essential for infection of mice. Infect. Immun. 74:6509-6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sikdar, R., and W. T. Doerrler. 2010. Inefficient Tat-dependent export of periplasmic amidases in an Escherichia coli strain with mutations in two DedA family genes. J. Bacteriol. 192:807-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohlenkamp, C., I. M. Lopez-Lara, and O. Geiger. 2003. Biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine in bacteria. Prog. Lipid Res. 42:115-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanley, N. R., K. Findlay, B. C. Berks, and T. Palmer. 2001. Escherichia coli strains blocked in Tat-dependent protein export exhibit pleiotropic defects in the cell envelope. J. Bacteriol. 183:139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steere, A. C., R. L. Grodzicki, A. N. Kornblatt, J. E. Craft, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, G. P. Schmid, E. Johnson, and S. E. Malawista. 1983. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompkins, K., B. Chattopadhyay, Y. Xiao, M. C. Henk, and W. T. Doerrler. 2008. Temperature sensitivity and cell division defects in an Escherichia coli strain with mutations in yghB and yqjA, encoding related and conserved inner membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 190:4489-4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, X. G., J. P. Scagliotti, and L. T. Hu. 2004. Phospholipid synthesis in Borrelia burgdorferi: BB0249 and BB0721 encode functional phosphatidylcholine synthase and phosphatidylglycerolphosphate synthase proteins. Microbiology 150:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu, Q., K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2008. Essential protective role attributed to the surface lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi against innate defences. Mol. Microbiol. 69:15-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, Q., K. McShan, and F. T. Liang. 2007. Identification of an ospC operator critical for immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:220-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu, Q., S. V. Seemanapalli, L. Lomax, K. McShan, X. Li, E. Fikrig, and F. T. Liang. 2005. Association of linear plasmid 28-1 with an arthritic phenotype of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 73:7208-7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, Y., and C. Li. 2009. Transcription and genetic analyses of a putative N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase in Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 290:164-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yook, K., and J. Hodgkin. 2007. MosI mutagenesis reveals a diversity of mechanisms affecting response of Caenorhabditis elegans to the bacterial pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum. Genetics 175:681-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y. M., and C. O. Rock. 2008. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:222-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, Z., K. A. White, A. Polissi, C. Georgopoulos, and C. R. H. Raetz. 1998. Function of Escherichia coli MsbA, an essential ABC family transporter, in lipid A and phospholipid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12466-12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.