Abstract

We investigated possible cross talk between endogenous antioxidants glutathione, spermidine, and glutathionylspermidine and drug efflux in Escherichia coli. We found that cells lacking either spermidine or glutathione are less susceptible than the wild type to novobiocin and certain aminoglycosides. In contrast, exogenous glutathione protects against both bactericidal and bacteriostatic antibiotics. The glutathione protection does not require the AcrAB efflux pump but fails in cells lacking TolC because exogenous glutathione is toxic to these cells.

In Escherichia coli and other Gram-negative bacteria, the major mechanism responsible for high levels of intrinsic resistance to antibiotics is active efflux, which decreases effective concentrations of drugs in the cytoplasm and periplasm (14). This efflux is carried out by multidrug efflux pumps comprising an inner membrane transporter from the resistance-nodulation-cell division superfamily, a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP), and an outer membrane channel. The best-characterized example of such pumps is AcrAB-TolC from E. coli, which forms a protein conduit spanning the entire two-membrane E. coli envelope (15). Among substrates of AcrAB-TolC are a broad range of antibiotics, detergents, dyes, organic solvents, and hormones.

Results of recent studies suggested that in addition to inhibiting specific intracellular targets, bactericidal antibiotics induce production of hydroxyl radicals, which are eventually responsible for cell death (6). Thus, besides drug efflux, the intracellular processes responsible for protection against oxidative damage might contribute to antibiotic resistance. E. coli cells produce two highly abundant compounds implicated in protection against reactive oxygen species: glutathione (GSH) and spermidine (SPE) (3, 13, 18). In addition, glutathionylspermidine (GSP), a conjugate of GSH and SPE, was also proposed previously to play a role in protection against oxidative stress (17). Whether these antioxidants protect E. coli cells against bactericidal antibiotics and how this protection is related to drug efflux remain unclear.

To investigate the possible contribution of endogenous antioxidants to protection against bactericidal antibiotics, we measured MICs of antibiotics and detergents for strains lacking GSP synthetase (ΔgspS), GSH synthetase (ΔgshB), and SPE synthetase (ΔspeE). In addition to gspS, the E. coli chromosome contains ygiC and yjfC genes, which encode proteins with significant homology to the C-terminal GSP synthetase domain of GspS (2). The high level of conservation of catalytically important residues in YgiC and YjfM suggested that these proteins could be GSP synthetases (5). We therefore constructed a mutant lacking ygiBC, yjfMC, and gspS and investigated its antibiotic susceptibility as well.

The mutants were either obtained from the Keio collection or constructed using the λ Red recombination approach (4). The MICs were determined by using Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 2-fold-increasing concentrations of antibiotic as described before (19). As shown in Table 1, E. coli cells that do not produce GSH and SPE did not become hypersusceptible to any of the tested compounds. Furthermore, MICs of amikacin and kanamycin increased 16-fold for ΔspeE cells and 4-fold for ΔgshB cells. In addition, ΔgshB cells were 8-fold less susceptible to novobiocin. Thus, endogenous SPE and GSH do not protect against antibiotics and, in some cases, are synergistic with them. The synergistic interactions between polyamines and aminoglycosides were reported before and attributed to interactions at the binding sites on ribosomes (8, 9, 12). It is surprising that similar interactions between GSH and certain antibiotics exist. Interestingly, although the ΔgspS mutant showed the same level of susceptibility as the wild type (WT), GD108 cells, lacking all three GSP enzymes, were 4-fold more susceptible than the WT to norfloxacin but not to other tested antibiotics. This result suggested that GSP enzymes function in the same, norfloxacin-sensitive pathway.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of E. coli strains to antibiotics

| Strain | Genotype | MICa (μg/ml) of: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERY | NOV | NOR | AMI | SPE | KAN | AMP | ||

| BW25113 | WT | 32 | 32 | 0.04 | 1 | 25 | 0.78 | 5 |

| GD100 | ΔtolC | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 1 | 12.5 | 0.78 | 5 |

| JW0117-1 | ΔspeE | 32 | 64 | 0.02 | 16 | 25 | 12.5 | 5 |

| JW2914-1 | ΔgshB | 64 | 256 | 0.04 | 4 | 25 | 6.25 | 10 |

| JW2956-1 | ΔgspS | 64 | 64 | 0.02 | 2 | 25 | 1.56 | 10 |

| GD108 | ΔygiBC ΔyjfMC ΔgspS | 64 | 32 | 0.01 | 1 | 25 | 1.56 | 5 |

| GD106 | ΔtolC ΔspeE | 1 | 1 | 0.005 | 8 | 25 | 6.25 | 5 |

| GD107 | ΔtolC ΔgshB | 1 | 1 | 0.0025 | 2 | 12.5 | 3.125 | 5 |

ERY, erythromycin; NOV, novobiocin; NOR, norfloxacin; AMI, amikacin; SPE, spectinomycin; AMP, ampicillin; KAN, kanamycin.

We next constructed strains that in addition to lacking antioxidants contained a deletion in the tolC gene, encoding an essential outer membrane component of multiple efflux pumps (1). As found previously, all ΔtolC mutants were highly susceptible to erythromycin, novobiocin, and norfloxacin but not to aminoglycosides and ampicillin (Table 1), presumably because the latter are not substrates of the major efflux pump AcrAB-TolC. In agreement with this conclusion, tolC deletion did not abolish an increase in the MICs of amikacin and kanamycin caused by the loss of SPE but completely eliminated the increase in MICs of novobiocin for ΔgshB cells. On the other hand, ΔtolC mutants lacking antioxidants became 2- to 4-fold more susceptible to norfloxacin, suggesting that these compounds contribute to the intrinsic resistance against this antibiotic. Although this contribution is not readily detectable in cells producing functional TolC, it becomes apparent in the absence of efflux.

GSH was previously reported to protect E. coli cells from fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides when added to growth medium, presumably by neutralizing hydroxyl radicals, which are involved in the action of these bactericidal antibiotics (10, 11). Therefore, we next investigated whether TolC is needed for this GSH-mediated protection against antibiotics. Consistent with findings of previous studies, the addition of increasing concentrations of GSH protected WT E. coli from norfloxacin and kanamycin (Table 2). In the presence of 15 mM GSH, the MICs of norfloxacin and kanamycin were 32-fold higher than those in the absence of GSH. Interestingly, GSH protection, up to a 4-fold increase in MICs, was also seen with erythromycin, a bacteriostatic antibiotic which presumably does not induce oxidative damage in cells. This result suggested that GSH action is broader than protection against oxidative damage.

TABLE 2.

MICs of norfloxacin, erythromycin, and kanamycin in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSHa

| Strain | Genotype | Norfloxacin MIC (μg/ml) with GSH concn (mM): |

Erythromycin MIC (μg/ml) with GSH concn (mM): |

Kanamycin MIC (μg/ml) with GSH concn (mM): |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | ||

| BW25113 | WT | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 1.28 | 128 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 1.56 | 25 | 50 | 50 |

| GD100 | ΔtolC | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | − | 4 | 4 | 4 | − | 1.56 | 25 | 50 | − |

| W4680AE | ΔacrAB ΔacrEF | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 32 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

−, no growth; ND, not determined. Strain W4680AE contains a kanamycin resistance cassette.

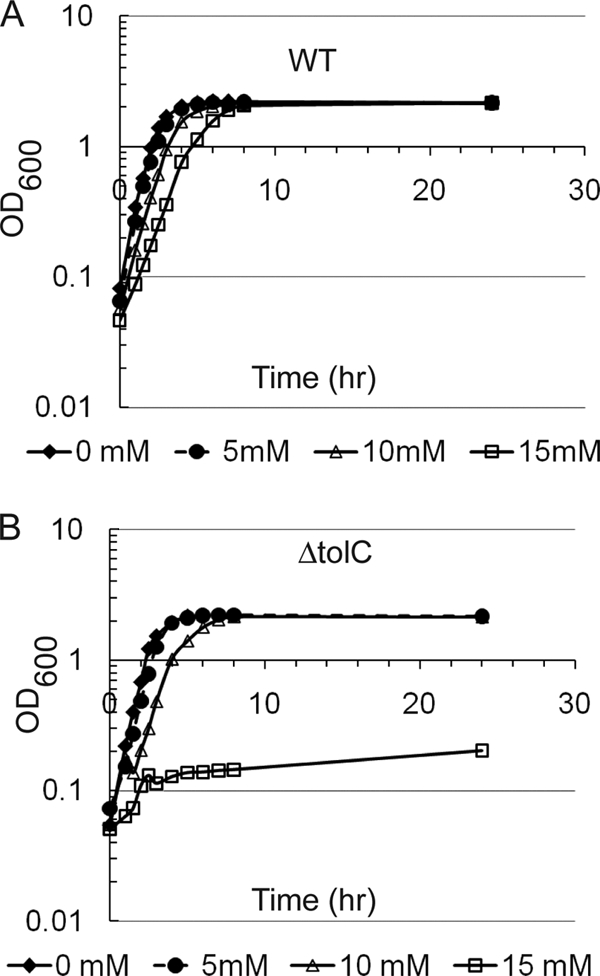

Albeit to a lesser extent, protection against norfloxacin and kanamycin by exogenous GSH in ΔtolC cells could also be seen, suggesting that this GSH activity does not require functional TolC (Table 2). In agreement with this evidence, W4680AE cells, lacking the efflux pumps AcrAB and AcrEF that function with TolC, were protected against norfloxacin by GSH. Thus, GSH protection is not dependent on drug efflux but is more efficient in the presence of TolC and efflux pumps. However, the effects of GSH on erythromycin differed for ΔtolC and ΔacrAB ΔacrEF cells. Significant, up to 8-fold, GSH protection against erythromycin could be seen for ΔacrAB ΔacrEF cells but not for ΔtolC cells. The difference between these two mutants is further evident from their different susceptibilities to GSH. A 15 mM concentration of GSH was highly toxic to ΔtolC cells, as demonstrated by complete inhibition of growth (Fig. 1 B). In contrast, only slight reduction of the growth rate was found for WT and ΔacrAB ΔacrEF cells (Fig. 1A and data not shown). These results suggest that defects in ΔtolC cells make them susceptible to GSH and that the lack of protection against erythromycin in these cells is likely due to GSH toxicity.

FIG. 1.

Exogenous GSH is toxic to ΔtolC cells. Shown are growth curves for strains BW25113 (A) and GD100 (B) in LB medium supplemented with 0, 5, 10, and 15 mM GSH.

In contrast to GSH, even at the 64 mM concentration, the exogenous SPE was well tolerated by ΔtolC mutants. No effect on MICs of antibiotics was found for exogenous SPE (data not shown).

Taken together, these results show that endogenous GSP and SPE modulate the susceptibility of E. coli to antibiotics. However, only certain antibiotics are affected, suggesting that this modulation occurs at antibiotic binding sites. In contrast, exogenous GSH increases MICs of various fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and erythromycin (this study and references 10 and 11). The effect of GSH is profound only when it is present in the medium, suggesting that its protective action is likely localized to the periplasm (Table 2). There is a growing body of evidence that GSH is exported into the periplasm and might play an important role in this cellular compartment as well. An ABC-type transporter, CydDC, originally identified by its requirement for assembly of the cytochrome bd-type terminal oxidase of E. coli, exports both cysteine and GSH into the periplasm (16). Also, glutaredoxin 3 exported into the periplasm promotes disulfide bond formation. This activity is not dependent on DsbB and requires the GSH biosynthetic pathway in the cytoplasm (7). Although the role of GSH in the periplasm remains obscure, it might be involved in the assembly of cytochromes and disulfide bonding in proteins (16).

It is not immediately clear why GSH is toxic to ΔtolC cells. But the decreased growth of the WT in the presence of 15 mM GSH suggests that GSH is toxic when it accumulates at high concentrations in the periplasm. The inhibitory effect of GSH is amplified in GD100 cells, which are under metabolic and membrane stress (5). Thus, it is likely that high concentrations of GSH in the periplasm compromise functions of membrane proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2R01-AI052293 to H.I.Z.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, C., C. Hughes, and V. Koronakis. 2001. Protein export and drug efflux through bacterial channel-tunnels. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:412-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollinger, J. M., Jr., D. S. Kwon, G. W. Huisman, R. Kolter, and C. T. Walsh. 1995. Glutathionylspermidine metabolism in Escherichia coli. Purification, cloning, overproduction, and characterization of a bifunctional glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14031-14041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chattopadhyay, M. K., C. W. Tabor, and H. Tabor. 2003. Polyamines protect Escherichia coli cells from the toxic effect of oxygen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:2261-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhamdhere, G., and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2010. Metabolic shutdown in Escherichia coli cells lacking the outer membrane channel TolC. Mol. Microbiol. 77:743-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwyer, D. J., M. A. Kohanski, B. Hayete, and J. J. Collins. 2007. Gyrase inhibitors induce an oxidative damage cellular death pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eser, M., L. Masip, H. Kadokura, G. Georgiou, and J. Beckwith. 2009. Disulfide bond formation by exported glutaredoxin indicates glutathione's presence in the E. coli periplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:1572-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldemberg, S. H., and I. D. Algranati. 1981. Polyamine requirement for streptomycin action on protein synthesis in bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 117:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldemberg, S. H., and I. D. Algranati. 1981. Polyamines and antibiotic effects on translation. Med. Biol. 59:360-367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goswami, M., S. H. Mangoli, and N. Jawali. 2007. Effects of glutathione and ascorbic acid on streptomycin sensitivity of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1119-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goswami, M., S. H. Mangoli, and N. Jawali. 2006. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:949-954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon, D. H., and C. D. Lu. 2007. Polyamine effects on antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2070-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masip, L., K. Veeravalli, and G. Georgiou. 2006. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8:753-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikaido, H. 2009. Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:119-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikaido, H., and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2001. AcrAB and related multidrug efflux pumps of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:215-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittman, M. S., H. C. Robinson, and R. K. Poole. 2005. A bacterial glutathione transporter (Escherichia coli CydDC) exports reductant to the periplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 280:32254-32261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith, K., A. Borges, M. R. Ariyanayagam, and A. H. Fairlamb. 1995. Glutathionylspermidine metabolism in Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 312(Pt. 2):465-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabor, C. W., and H. Tabor. 1976. 1,4-Diaminobutane (putrescine), spermidine, and spermine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 45:285-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tikhonova, E. B., Q. Wang, and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2002. Chimeric analysis of the multicomponent multidrug efflux transporters from gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:6499-6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]