Abstract

A total of 71 fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (45 methicillin-resistant and 26 methicillin-susceptible) isolates were examined for the presence of resistance determinants. Among 45 fusidic acid-resistant methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), isolates, 38 (84%) had fusA mutations conferring high-level resistance to fusidic acid (the MIC was ≥128 μg/ml for 22/38), none had fusB, and 7 (16%) had fusC. For 26 fusidic acid-resistant methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), only 3 possessed fusA mutations, but 15 (58%) had fusB and 8 (31%) had fusC. Low-level resistance to fusidic acid (MICs ≤ 32 μg/ml) was found in most fusB- or fusC-positive isolates. For 41 isolates (38 MRSA and 3 MSSA), with fusA mutations, a total of 21 amino acid substitutions in EF-G (fusA gene) were detected, of which R76C, E444K, E444V, C473S, P478S, and M651I were identified for the first time. The nucleotide sequencing of fusB and flanking regions in an MSSA isolate revealed the structure of partial IS257-aj1-LP-fusB-aj2-aj3-IS257-partial blaZ, which is identical to the corresponding region in pUB101, and the rest of fusB-carrying MSSA isolates also show similar structures. On the basis of spa and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) typing, two major genotypes, spa type t037-SCCmec type III (t037-III; 28/45; 62%) and t002-II (13/45; 29%), were predominant among 45 MRSA isolates. By pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis, 45 MRSA isolates were divided into 12 clusters, while 26 MSSA isolates were divided into 15 clusters. Taken together, the distribution of fusidic acid resistance determinants (fusA mutations, fusB, and fusC) was quite different between MRSA and MSSA groups.

Fusidic acid has been used as a topical agent for skin infection and for some systemic infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus (12). Fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus has been reported in many countries, with the prevalence ranging from 0.3 to 52.5%, and the occurrences of resistance determinants were remarkably different among different countries (5, 6). The rate of fusidic acid resistance in S. aureus in our hospital each year is about 3 to 6%. Although this frequency is not very high, the understanding of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms still is very important.

Two major fusidic acid resistance mechanisms have been reported in S. aureus: the alteration of the drug target site (4, 24, 25), which is due to mutations in fusA (encoding elongation factor G [EF-G]) (24, 28) or rplF (or FusE, encoding ribosome protein L6) (19, 25), and the protection of the drug target site by FusB family proteins, including fusB, fusC, and fusD (27, 30). Point mutations in fusA occur mainly in domain III of EF-G and usually permit normal colony size and growth rate, conferring the FusA class resistance (20, 25). Fusidic acid-resistant small-colony variant (SCV) isolates, referred to as the FusA-SCV class, were due mostly to mutations in domain V of EF-G (19, 25). Some fusA point mutations may compromise fitness during growth in vivo and in vitro, but these costs may be partly or fully compensated for by acquiring additional amino acid substitutions (24). Another subclass of mutations, located in rplF (32), is referred to as the FusE class, which confers fusidic acid resistance to SCV isolates.

Acquired fusidic acid resistance genes found in Staphylococcus spp. include fusB, fusC, and fusD. The genes fusB and fusC were found in S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (22, 27, 30, 34), and fusD was an intrinsic factor causing fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus saprophyticus (30). The fusB determinant originally was found on the plasmid pUB101 in S. aureus (26). Later, the fusB determinant also was found on a transposon-like element (27) or in a staphylococcal pathogenicity island (29).

In this study, we analyzed fusidic acid resistance determinants among methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) isolates for which fusidic acid had a MIC of ≥2 μg/ml. The distribution of fusidic acid resistance determinants was found different in MRSA and MSSA groups. Furthermore, to understand the phylogenetic relationship of resistance determinant-containing isolates, genotyping also was performed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Seventy-one fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus isolates (MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml) were tested in this study, including 45 MRSA and 26 MSSA isolates. Isolates were collected between October 2002 and January 2007 in the Bacteriology Laboratory, National Taiwan University Hospital, a 2,500-bed teaching hospital in northern Taiwan. The 45 MRSA isolates were chosen randomly from each month, representing about half of the collection. The 26 fusidic acid-resistant MSSA isolates were selected from all MSSA isolates in the collection period. Only one isolate per patient was included. The sources of 71 isolates included blood (59), external ear (2), pus (2), sputum (2), wound (2), synovial fluid (1), abscess (1), ascites (1), and burn (1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by standard agar dilution according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Bacterial inocula were prepared by direct colony suspension to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standards. A bacterial density of 104 CFU/spot was inoculated on Mueller-Hinton agars with various concentrations of fusidic acid (0.03 to 128 μg/ml) by using a Steers replicator, and the plates were incubated at 33 to 35°C for 16 to 20 h. S. aureus ATCC 29213 was used as the control organism. The breakpoint of fusidic acid resistance was 2 μg/ml (8).

Detection of fusidic acid resistance determinants by PCR.

To detect fusA mutations, the DNAs were amplified with primers fusA-F and fusA-R (see Table S1in the supplemental material) and then sequenced by fusA −68_−49, fusA 404_425, fusA 946_968, and fusA down 47_25 (Table S1). The presence of acquired fusidic acid resistance determinants (fusB, fusC, and fusD) was detected by PCR (Table S1). PCRs were carried out using a DNA thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) with 30 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s; at 45°C for fusA, 50°C for fusB and fusC, and 57°C for fusD), and extension (72°C for 2 min for fusA and 30 s for the others), followed by a final extension step (72°C for 10 min). The expected amplicons were 492 bp for fusB, 411 bp for fusC, and 465 bp for fusD. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels.

Southern blotting.

To clone and sequence the fusB fragment in MSSA, Southern blotting was used to estimate the fragment sizes digested by restriction enzymes and to perform further cloning procedures. Southern blot analysis was performed with the DNA from a representative isolate, NTUH-5020, using restriction enzymes (BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, PstI, SalI, and XbaI) (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and detected with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled fusB-specific probe prepared by PCR amplification (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The hybridization assay was performed by using a commercial kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany).

Nucleotide sequencing of fusB and flanking regions.

To determine the sequence of fusB and its flanking regions, an LA PCR in vitro cloning kit (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Japan) was used. The LA PCR was carried out with the XbaI-digested DNA fragments. After ligating the XbaI-digested DNA fragments with cassette adapters, the amplification was performed with cassette primers (C1 for the first PCR and C2 for the nested PCR) supplied by the manufacturer and target gene-specific primers (fusB 437-465F for the first PCR and fusB 531-559F for the nested PCR) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The fusB upstream sequences were amplified with a pair of primers, IS 257 518-499R and fusB 283-254R (Table S1). Amplification products subsequently were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the Taq BigDye deoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

SCCmec typing.

The staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) types were determined by the detection of ccr genes and the types of mec complexes (7). The detection of ccrAB was carried out by a multiplex PCR using a mixture of four primers: a degenerate forward primer (β2) and three reverse primers (α2, α3, and α4) specific to ccrA1B1 (SCCmec type I) (0.7 kb), ccrA2B2 (SCCmec type II or type IV) (1 kb), and ccrA3B3 (SCCmec type III) (1.6 kb) (13). The determination of the presence of ccrC (SCCmec type V) was carried out by PCR with primers γF and γR (520 bp) (14). Another PCR amplification was performed to detect the ccrC2 gene (257 bp; SCCmec type VII, previously named SCCmec type VT) (33). mec complex class A was determined by the amplification of the mecI gene by mecI-1 and mecI-2 (481 bp) (10). A 1,287-bp fragment amplified by mecRA1 (located in mecR1) and mDA2 (located in IS1272) was used to identify mec complex class B (17). Transposase C of Tn554 was detected by amplification with the primer pair Tn554C F and Tn554C R (2). The primers mentioned above are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

spa typing and multilocus sequence typing.

The spa typing was performed as previously described (31). An amplification of the staphylococcal protein A gene (spa) was carried out with the primer pair spa-1095F and spa-1517R (see Table S1). Since this pair of primers couldn't produce a spa PCR product in NTUH-2803, another forward primer, spa-1063F, was used (18). The spa type was determined by using the Ridom Spaserver website (http://www.spaserver.ridom.de) (11). The multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was analyzed in eight MRSA isolates, representing different spa types according to a method described previously (9).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

The genotyping of fusidic acid-resistant MRSA and MSSA was performed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Genomic DNAs were prepared and digested with SmaI (New England BioLabs) (23) and then separated in a CHEF-DR II apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). PFGE was carried out at 200 V and 13°C for 20 h, with pulse times ranging from 5 to 60 s. The pulsotypes were analyzed by BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). The dendrogram of pulsotype relationships was produced by the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages (UPGMA) based on Dice similarity indices.

RESULTS

MIC of fusidic acid.

Among 45 fusidic acid-resistant MRSA isolates, the MICs of fusidic acid ranged from 4 to >128 μg/ml, with a 50% minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC50) of 32 μg/ml and MIC90 of >128 μg/ml. The fusidic acid MICs for 26 fusidic acid-resistant MSSA isolates ranged from 2 to 32 μg/ml, giving a MIC50 of 8 μg/ml and MIC90 of 16 μg/ml. The results indicated that the level of fusidic acid resistance was higher in MRSA than in MSSA.

Prevalence of fusidic acid resistance determinants.

To determine the prevalence of fusidic acid resistance determinants among 45 MRSA and 26 MSSA isolates, the entire fusA gene was sequenced, and other fusidic acid resistance genes (fusB, fusC, and fusD) were detected by PCR. Point mutations in fusA were found in 38/45 (84%) MRSA isolates, while 3 of 26 fusidic acid-resistant MSSA isolates possessed fusA point mutations (Table 1). Amplifications with primers specific for fusB, fusC, and fusD (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) revealed that none of the 45 MRSA isolates possessed either fusB or fusD, but seven MRSA isolates carried fusC (16%). The fusB gene was prevalent in MSSA isolates (15/26; 58%). Eight MSSA isolates (31%) carried the fusC determinant. Neither MRSA nor MSSA carried the fusD determinant (Table 1). The presence of fusB and fusC also was confirmed by Southern blotting with specific probes (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Fusidic acid resistance determinants detected among MRSA and MSSA isolates

| Species (no. of isolates showing fusidic acid MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml) | No. (%) of isolates with different fusidic acid resistance determinants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fusA mutation | fusB | fusC | fusD | |

| MRSA (45) | 38 (84) | 0 (0) | 7 (16) | 0 (0) |

| MSSA (26) | 3 (12) | 15 (58) | 8 (31) | 0 (0) |

| Total (71) | 41 (58) | 15 (21) | 15 (21) | 0 (0) |

Relationship of MIC to fusidic acid resistance determinants.

The correlation of MIC to fusidic acid resistance determinants among MRSA and MSSA isolates was analyzed (Table 2). Isolates with fusA mutations usually had higher levels of fusidic acid resistance (the MIC for more than half of the isolates [22/41] was ≥128 μg/ml), while isolates with other determinants (fusB or fusC) had lower levels of resistance to fusidic acid (MICs ≤ 32 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of fusidic acid MIC and resistance determinants among fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus isolates

| Resistance determinant (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates with different fusidic acid MIC (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-16 | 32-64 | ≥128 | |

| fusA point mutation (41) | 15 | 4 | 22 |

| fusB (15) | 14 | 1 | 0 |

| fusC (15) | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (71) | 44 | 5 | 22 |

Mutations in fusA.

We determined the nucleotide sequences of fusA from all MRSA and MSSA isolates. Point mutations in fusA were detected in 38 MRSA and 3 MSSA isolates. A total of 22 different nucleotide substitutions causing 21 amino acid exchanges at 17 different positions in EF-G were found (Table 3). Single-amino-acid substitutions were found in 21 MRSA and 3 MSSA isolates, and two amino acid substitutions were found in the other 17 MRSA isolates. Most amino acid substitutions occurred in domain III of EF-G (14/21; 67%), followed by domain I (5/21; 24%), while only one substitution was found in domain II and domain V. Six different amino acid substitutions were not previously reported, including R76C (in domain I), E444V (domain III), E444K (domain III), C473S (domain III), P478S (domain III), and M651I (domain V) (Table 3). A high frequency of amino acid substitutions arose at His-457 and Leu-461 of EF-G. Even a single-amino-acid substitution, such as H457Y or L461K, could result in a high level of fusidic acid resistance (MIC ≥ 128 μg/ml).

TABLE 3.

FusA (EF-G) alternation sites detected in 41 S. aureus isolates

| Amino acid substitution (domaina) | Nucleotide substitution | No. of isolates | Fusidic acid MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P404Lb | CCA→CTA | 2 (1 MRSA, 1 MSSA) | 8, 16 |

| P406Lb | CCA→CTA | 1 | 16 |

| E444Kf | GAA→AAA | 1 | 16 |

| G451Vb | GGT→GTT | 2 | 8, 16 |

| M453Id | ATG→ATA | 2 | 8 |

| H457Qg | CAC→CAA | 1 | 8 |

| H457Yb | CAC→TAC | 5 | 128, >128 |

| L461Kb | TTA→AAA | 6 | >128 |

| L461Sb | TTA→TCA | 2 | 4, 8 |

| P478Sf | CCA→TCA | 1 (MSSA) | 8 |

| M651I (domain V)f | ATG→ATA | 1 (MSSA) | 2 |

| M16I (domain I)c, H457Yb | ATG→ATA, CAC→TAC | 3 | 16, 32, 64 |

| A67T (domain I)e, H457Yb | GCA→ACA, CAC→TAC | 3 | 128, >128 |

| A70V (domain I)c, H457Yb | GCA→GTA, CAC→TAC | 1 | >128 |

| A71V (domain I)c, P404Lb | GCT→GTT, CCA→CTA | 1 | 8 |

| R76C (domain I)f, H457Yb | CGT→TGT, CAC→TAC | 1 | >128 |

| A376V (domain II)c, L456Fb | GCT→GTT, CTT→TTT | 1 | 32 |

| E444Vf, L461Fb | GAA→GTA, TTA→TTT | 1 | 32 |

| H457Qg, L461Fb | CAC→CAA, TTA→TTT | 4 | 128 |

| H457Qg, L461Kb | CAC→CAG, TTA→AAA | 1 | >128 |

| L461Kb, C473Sf | TTA→AAA, TGT→AGT | 1 | >128 |

No domain specification indicates domain III of EF-G.

The amino acid substitutions have been identified as compensatory mutations in S. aureus (24).

Reported for Salmonella typhimurium (15).

The amino acid substitution has been reported to have no impact on fusidic acid resistance or compensation for fitness in S. aureus (3).

The amino acid substitutions were first identified among S. aureus isolates.

The amino acid substitution H457Q was recently reported by Castanheira et al. (5).

Genetic structure of fusB-containing regions in MSSA.

Since most of the fusidic acid-resistant MSSA carried fusB, we determined the sequences of a 4,765-bp fragment containing fusB and its flanking regions in an MSSA isolate, NTUH-5020. The nucleotide sequences revealed the organization of partial IS257-aj1-LP-fusB-aj2-aj3-IS257-partial blaZ. The genetic structures of the fusB fragments in the other 15 clinical isolates were further tested by PCR mapping with two pairs of primers, IS 257 518-499R/fusB 283-254R for the upstream region and fusB 531-559F/IS 257 33-52F (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) for the downstream region of fusB. In addition, we confirmed the structure of fusB fragment by Southern blotting (data not shown). The results indicated that the genetic structures of fusB elements among our MSSA isolates were very similar.

Genotyping of MRSA by spa type, SCCmec type, and MLST.

To understand the phylogenetic relationships between the fusidic acid-resistant MRSA isolates, we determined spa types and SCCmec types of the MRSA isolates. The 45 MRSA isolates belonged to five different spa types. The majority (42/45) of MRSA isolates belonged to two major spa types, t037 (29/45; 64%) and t002 (13/45; 29%). The remaining three isolates belonged to the spa types t437, t036, and t037*. The spa type t037* (repeat ID based on Ridom Spaserver website, 190-12-16-2-25-17-24) differ from t037 with only one nucleotide difference.

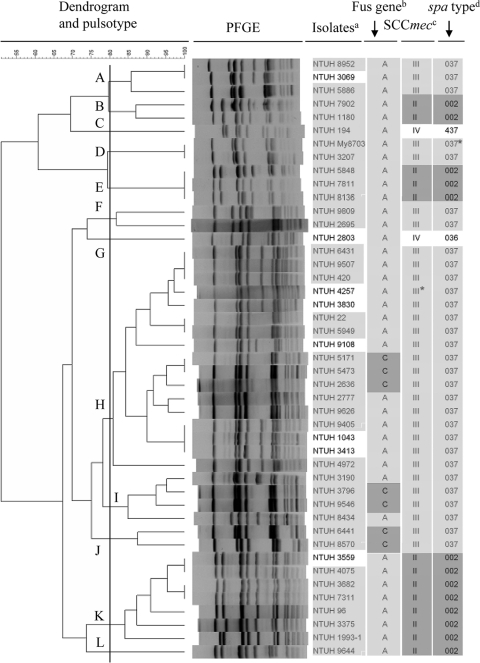

Three SCCmec types (II, III, and IV) were identified among the 45 fusidic acid-resistant MRSA isolates. The majority (29/45; 64%) contained SCCmec type III. Thirteen (29%) were SCCmec type II, and only two (4%) were SCCmec type IV. One isolate, NTUH-4257 (spa type t037), possessing mec complex A, ccrC, and transposase C of Tn554, was tentatively classified as SCCmec III* (Fig. 1). The 38 MRSA isolates with fusA mutations belonged to SCCmec types II, III, or IV, while all (seven) strains carrying fusC were restricted to SCCmec type III.

FIG. 1.

Genotypes and fusidic acid resistance determinants among 45 fusidic acid-resistant MRSA isolates. The dendrogram was produced by BioNumerics software, showing distance calculated by the Dice similarity index of SmaI-digested DNA fragments. The degree of similarity is shown in the scale. Footnotes: a, light gray indicates isolates collected from blood specimens; b, resistance determinants of resistance to fusidic acid (A, fusA point mutation [light gray]; C, fusC determinant [dark gray]); c, SCCmec type based on ccr gene and mec complex (light gray, SCCmec type III; dark gray, SCCmec type II; SCCmec type III*, undetermined but possibly SCCmec type III [ccrA3B3 PCR failed], which contained mec complex A, ccrC, and transposase C of Tn554); d, spa type based on data from the Ridom Spaserver website (http://www.spaserver.ridom.de) (light gray, spa type t037 [repeat ID, 15-12-16-2-25-17-24] and spa type t037* [repeat ID, 190-12-16-2-25-17-24; one nucleotide different from t037]; dark gray, spa type t002).

The MLST was analyzed in eight MRSA isolates, with two representing spa t002 and SCCmec type II (NTUH-7811 and NTUH-4075), four representing spa t037 (including three SCCmec type III [NTUH-420, NTUH-5171, and NTUH-1043] and one undetermined but possible SCCmec III, NTUH-4257), one representing spa t437 (SCCmec type IV; NTUH-194), and one representing t036 (SCCmec type IV; NTUH-2803). The sequence type (ST) for four isolates of spa type t037 was ST239. The ST of two isolates with spa type t002 was ST5. The STs for two isolates containing SCCmec type IV were ST59 for spa type t437 (NTUH-194) and ST254 for spa type t036 (NTUH-2803), respectively.

PFGE analysis in MRSA and MSSA.

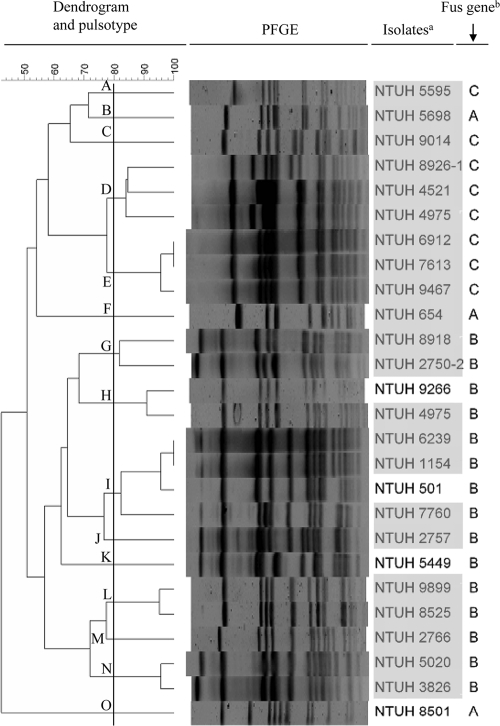

To determine the genetic diversity among 45 fusidic acid-resistant MRSA and 26 MSSA isolates, we performed PFGE and assigned pulsotypes to clusters with >80% similarity with BioNumerics software, based on the Dice similarity index in the dendrogram created by the UPGMA algorithm. The 45 MRSA isolates were divided into 12 clusters (Fig. 1), while 26 MSSA isolates were divided into 15 clusters (Fig. 2). Pulsotype H was the most frequent pulsotype in MRSA (17/45; 38%). Some isolates belonging to a closely related pulsotype carried different fusA mutations, such as NTUH-My8703 (P406L) and NTIH-3207 (A71V and P404L) in pulsotype D. Seven MRSA containing fusC distributed in three PFGE types (Fig. 1). MSSA isolates containing fusB or fusC clustered separately (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Genotypes and fusidic acid resistance determinants among 26 fusidic acid-resistant MSSA isolates. The dendrogram was produced by BioNumerics software, showing distance calculated by the Dice similarity index of SmaI-digested DNA fragments. The degree of similarity is shown in the scale. Footnotes: a, light gray, isolates collected from blood specimens; b, resistance determinants to fusidic acid (B, fusB; C, fusC).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown geographical differences in the prevalence of fusidic acid resistance determinants among S. aureus. Lannergard et al. reported that approximately equal frequencies of the FusA, FusB, and FusC classes were found in bacteremia isolates of S. aureus (19). In U.S. and European collections, fusC was more prevalent than fusB in S. aureus strains (5, 6). However, the previous studies did not compare the difference between MRSA and MSSA. In the present study, we found that the prevalence of fusidic acid resistance determinants was quite different between MRSA and MSSA groups. The predominant determinants in MRSA were fusA mutations, followed by fusC, and none carried fusB determinant. In contrast, most MSSA carried the acquired resistance gene fusB followed by fusC, with only three isolates showing fusA mutations. In our isolates, the fusA mutations and acquired FusB-family determinants were not detected in a same strain, which might be due to the inability of different determinants to interact synergistically (27).

In agreement with previous reports, isolates with fusA mutations usually displayed higher levels of resistance to fusidic acid (MICs ranging from 4 to >128 μg/ml). Previous reports and the findings presented here indicate that single-amino-acid substitutions in EF-G can lead to high levels of resistance to fusidic acid (for example, H457Y and L461K). The MIC of fusidic acid in MSSA carrying fusB ranged from 4 to 32 μg/ml, which was much lower than those in MRSA with fusA mutations. The MIC of fusidic acid in MRSA and MSSA isolates carrying fusC ranged from 8 to 16 μg/ml, which is similar to findings in other reports (30).

Among 41 isolates (38 MRSA and 3 MSSA) with fusA mutations, a total of 22 types of nucleotide changes causing 21 amino acid substitutions were found. Of these, most (14 mutations) occurred in domain III, followed by domain I (5 mutations), one in domain II, and one in domain V. Mutations with M16I, A70V, A71V in domain I, and A376V in domain II have been reported as compensatory mutations in S. aureus (24). Nine amino acid changes in domain III have previously been reported to be associated with fusidic acid resistance in S. aureus (4, 24), and one (M453I) has been identified in Salmonella typhimurium (15). The amino acid substitution, A67T, has been reported as having no impact on fusidic acid resistance or compensation for fitness in S. aureus (3). The importance of three mutations of fusA (P406L, H457Y, and L461K) for fusidic acid resistance in S. aureus has been directly proved by site-directed mutagenesis (4). Among the fusA mutations detected in the present study, six (R76C, E444K, E444V, C473S, P478S, and M651I) were first reported (Table 3). Of these, mutations of E444V, E444K, C473S, P478S located in domain III, and M651I located in domain V of EF-G were very possibly a cause of fusidic acid resistance. The amino acid substitution R76C was found to be accompanied with another fusA mutation (Table 3). Since A70V and A71V have been reported as fitness compensation mutations, it is possible the R76C play the same role. Amino acid alteration at position 457 (His) replaced by tyrosine has been reported previously to produce a MIC of 64 μg/ml (4). Substitution at His-457 with glutamine had not been reported when we prepared the first version of the manuscript. However, it was just recently published by Castanheira et al. (5, 6). This result indicated that different mutations at the same amino acid position result in different levels of resistance. The role of the six newly found amino acid substitutions in fusA is unknown and needs further investigation.

In agreement with previous reports, the fusB genes in our MSSA isolates are located in a genetic structure identical to that of pUB101 (26, 34). However, the MICs of fusidic acid for our MSSA isolates were lower than that for pUB101 isolates (26). Why was the fusB gene detected only in MSSA and not in MRSA isolates? PFGE analysis demonstrated the heterogeneity of pulsotypes among the fusB-containing MSSA isolates, not in a single clone. However, isolates with fusB or fusC formed separate clusters. Thus, the horizontal and clonal spreading may have both contributed to the fusidic acid resistance in S. aureus isolates.

On the basis of spa and SCCmec typing, a major genotype, spa type t037-SCCmec type III (t037-III; 28/45; 62%), corresponding to PFGE types A, D, F, H, I, and J, was found to be dominant in fusidic acid-resistant MRSA, followed by t002-II (13/45; 29%), corresponding to PFGE types B, E, K, and L. The MLST analysis with representatives of different spa types indicated that isolates of spa t037, t002, t437, and t036 were identified as ST239, ST5, ST59, and ST254, respectively. Previous studies have shown that spa type t037 with SCCmec type III belonged to ST239 or ST241, while spa type t002 with SCCmec type II belonged to ST5 (21). ST239-SCCmec type III (ST239-III) or ST241-III, which was known as the Brazil/Hungary clone, and ST5-II, which was known as the New York/Japan clone, were common in Asia (1, 16). In general, the MRSA isolates with fusA mutations or carrying fusC were distributed among diverse PFGE types. The MSSA isolates containing fusB or fusC formed separate clusters. However, different types of fusA mutations could be found in MRSA isolates with identical SCCmec type, spa type, and closely related PFGE types (found in pulsotypes A, D, E, H, and K), suggesting that they originate from the same clone but were independently selected by antibiotic pressure.

In conclusion, different resistance determinants were responsible for fusidic acid resistance in MRSA and MSSA isolates. Resistance to fusidic acid in MRSA was associated mostly with fusA point mutations. The acquired FusB-family determinants were responsible for fusidic acid resistance in MSSA. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that fusidic acid-resistant MRSA and MSSA belonged to different lineages.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant NSC 96-2320-B-002-013 from the National Science Council of Taiwan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 20 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa, M., M. I. Crisostomo, I. S. Sanches, J. S. Wu, J. Fuzhong, A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2003. Frequent recovery of a single clonal type of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in two hospitals in Taiwan and China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:159-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakere, G., S. Nadig, T. Ito, X. X. Ma, and K. Hiramatsu. 2009. A novel type-III staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) variant among Indian isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besier, S., A. Ludwig, V. Brade, and T. A. Wichelhaus. 2005. Compensatory adaptation to the loss of biological fitness associated with acquisition of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1426-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besier, S., A. Ludwig, V. Brade, and T. A. Wichelhaus. 2003. Molecular analysis of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 47:463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castanheira, M., A. A. Watters, J. M. Bell, J. D. Turnidge, and R. N. Jones. 2010. Fusidic acid resistance rates and prevalence of resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. isolated in north America and Australia, 2007-2008. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3614-3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castanheira, M., A. A. Watters, R. E. Mendes, D. J. Farrell, and R. N. Jones. 2010. Occurrence and molecular characterization of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. from European countries (2008). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1353-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chongtrakool, P., T. Ito, X. X. Ma, Y. Kondo, S. Trakulsomboon, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, T. Chavalit, J. H. Song, and K. Hiramatsu. 2006. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in 11 Asian countries: a proposal for a new nomenclature for SCCmec elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1001-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutant, C., D. Olden, J. Bell, and J. D. Turnidge. 1996. Disk diffusion interpretive criteria for fusidic acid susceptibility testing of staphylococci by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25:9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright, M. C., N. P. J. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for the characterization of methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanssen, A. M., G. Kjeldsen, and J. U. Sollid. 2004. Local variants of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec in sporadic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci: evidence of horizontal gene transfer? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:285-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmsen, D., H. Claus, W. Witte, J. Rothganger, D. Turnwald, and U. Vogel. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442-5448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howden, B. P., and M. L. Grayson. 2006. Dumb and dumber-the potential waste of a useful antistaphylococcal agent: emerging fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:394-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito, T., X. X. Ma, F. Takeuchi, K. Okuma, H. Yuzawa, and K. Hiramatsu. 2004. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2637-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johanson, U., and D. Hughes. 1994. Fusidic acid-resistant mutants define three regions in elongation factor G of Salmonella typhimurium. Gene 143:55-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko, K. S., J. Y. Lee, J. Y. Suh, W. S. Oh, K. R. Peck, N. Y. Lee, and J. H. Song. 2005. Distribution of major genotypes among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Asian countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:421-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi, N., S. Urasawa, N. Uehara, and N. Watanabe. 1999. Distribution of insertion sequence-like element IS1272 and its position relative to methicillin resistance genes in clinically important staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2780-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koreen, L., S. V. Ramaswamy, E. A. Graviss, S. Naidich, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2004. spa typing method for discriminating among Staphylococcus aureus isolates: implications for use of a single marker to detect genetic micro- and macrovariation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:792-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lannergård, J., T. Norstrom, and D. Hughes. 2009. Genetic determinants of resistance to fusidic acid among clinical bacteremia isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2059-2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurberg, M., O. Kristensen, K. Martemyanov, A. T. Gudkov, I. Nagaev, D. Hughes, and A. Liljas. 2000. Structure of a mutant EF-G reveals domain III and possibly the fusidic acid binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 303:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, Y., H. Wang, N. Du, E. Shen, H. Chen, J. Niu, H. Ye, and M. Chen. 2009. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:512-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaws, F., I. Chopra, and A. J. O'Neill. 2008. High prevalence of resistance to fusidic acid in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1040-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray, B. E., K. V. Singh, J. D. Heath, B. R. Sharma, and G. M. Weinstock. 1990. Comparison of genomic DNAs of different enterococcal isolates using restriction endonucleases with infrequent recognition sites. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:2059-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagaev, I., J. Bjorkman, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 2001. Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norström, T., J. Lannergard, and D. Hughes. 2007. Genetic and phenotypic identification of fusidic acid-resistant mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4438-4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien, F. G., C. Price, W. B. Grubb, and J. E. Gustafson. 2002. Genetic characterization of the fusidic acid and cadmium resistance determinants of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pUB101. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Neill, A. J., and I. Chopra. 2006. Molecular basis of fusB-mediated resistance to fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 59:664-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Neill, A. J., A. R. Larsen, A. S. Henriksen, and I. Chopra. 2004. A fusidic acid-resistant epidemic strain of Staphylococcus aureus carries the fusB determinant, whereas fusA mutations are prevalent in other resistant isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3594-3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neill, A. J., A. R. Larsen, R. Skov, A. S. Henriksen, and I. Chopra. 2007. Characterization of the epidemic European fusidic acid-resistant impetigo clone of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1505-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neill, A. J., F. McLaws, G. Kahlmeter, A. S. Henriksen, and I. Chopra. 2007. Genetic basis of resistance to fusidic acid in staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1737-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shopsin, B., M. Gomez, S. O. Montgomery, D. H. Smith, M. Waddington, D. E. Dodge, D. A. Bost, M. Riehman, S. Naidich, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sköld, S. E. 1982. Chemical cross-linking of elongation factor G to both subunits of the 70-S ribosomes from Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 127:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takano, T., W. Higuchi, T. Otsuka, T. Baranovich, S. Enany, K. Saito, H. Isobe, S. Dohmae, K. Ozaki, M. Takano, Y. Iwao, M. Shibuya, T. Okubo, S. Yabe, D. Shi, I. Reva, L. J. Teng, and T. Yamamoto. 2008. Novel characteristics of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains belonging to multilocus sequence type 59 in Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:837-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yazdankhah, S. P., A. W. Asli, H. Sorum, H. Oppegaard, and M. Sunde. 2006. Fusidic acid resistance, mediated by fusB, in bovine coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1254-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.