Abstract

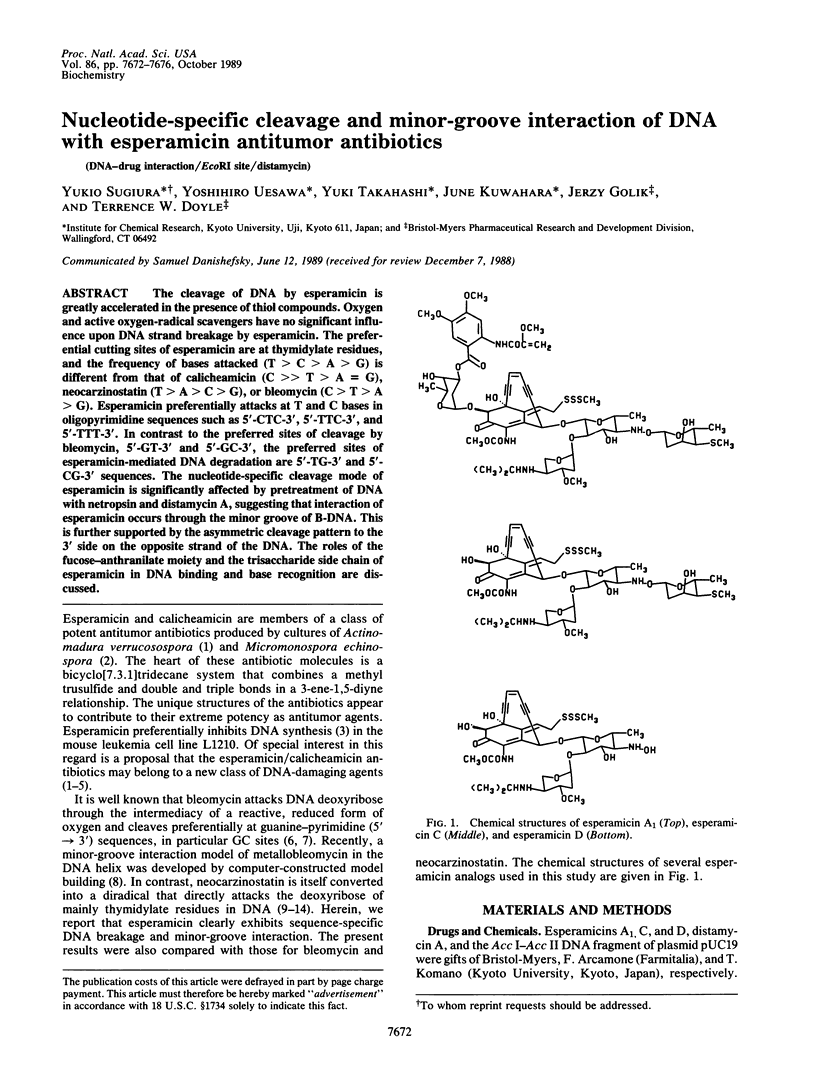

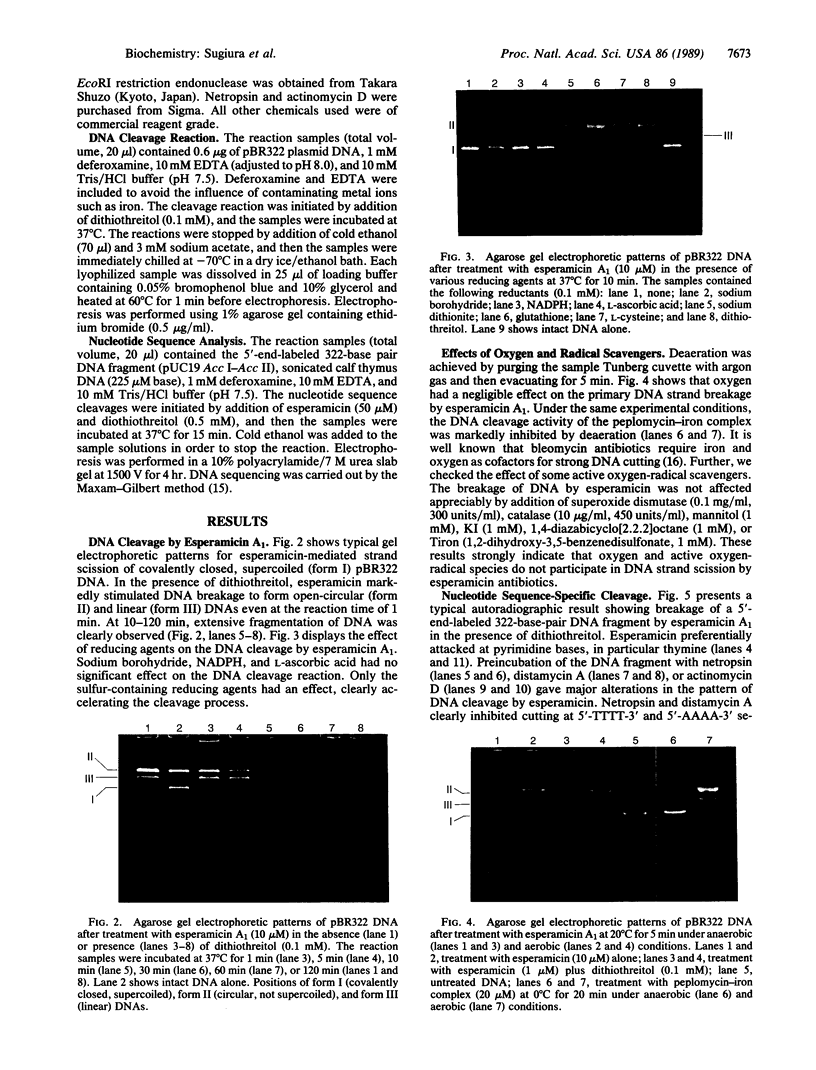

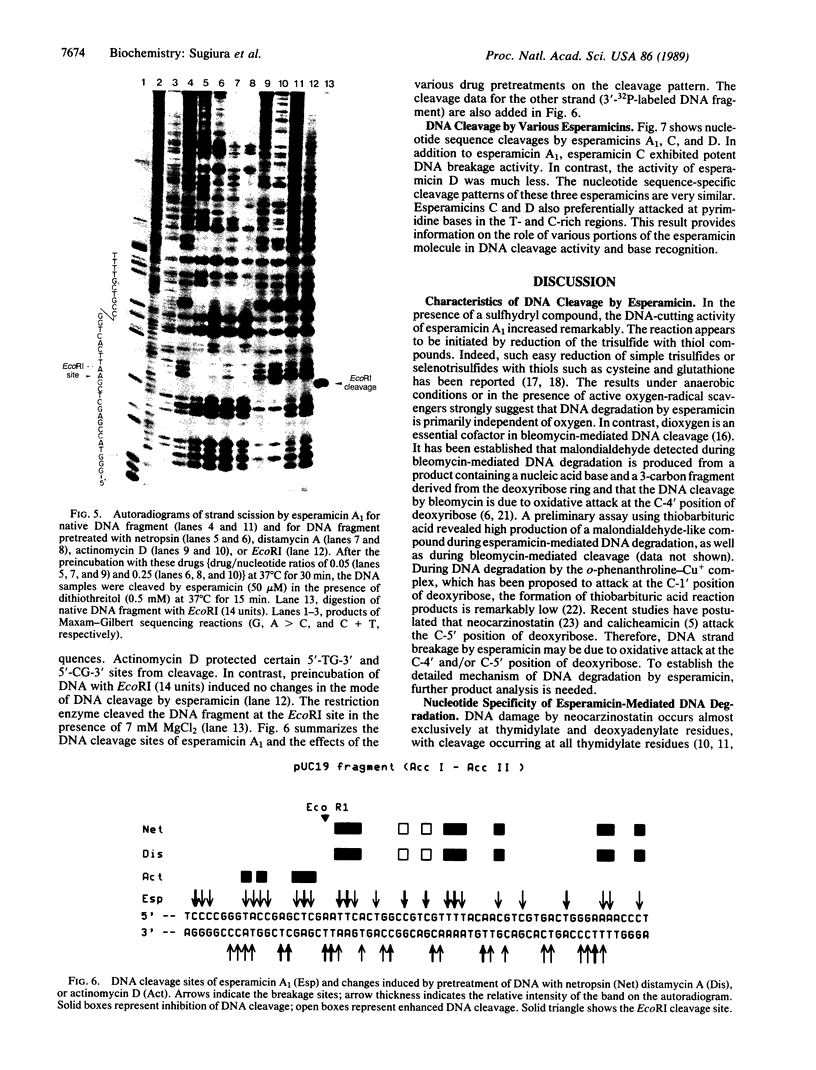

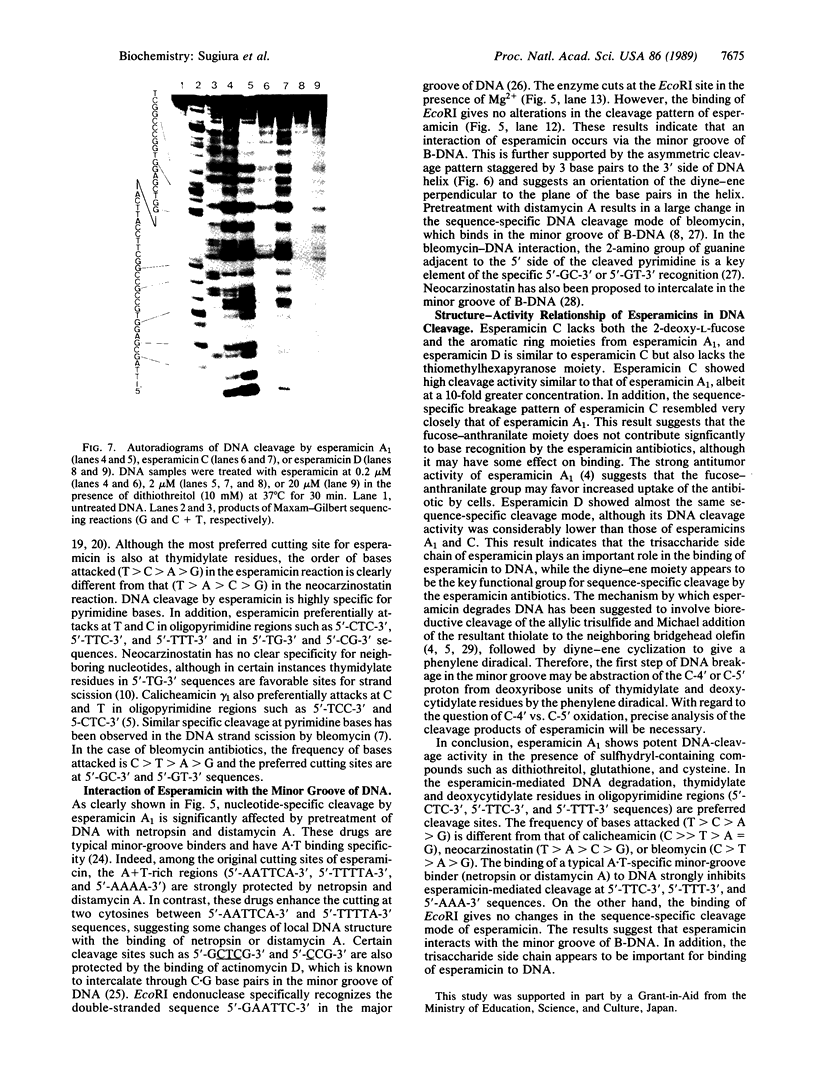

The cleavage of DNA by esperamicin is greatly accelerated in the presence of thiol compounds. Oxygen and active oxygen-radical scavengers have no significant influence upon DNA strand breakage by esperamicin. The preferential cutting sites of esperamicin are at thymidylate residues, and the frequency of bases attacked (T greater than C greater than A greater than G) is different from that of calicheamicin (C much greater than T greater than A = G), neocarzinostatin (T greater than A greater than C greater than G), or bleomycin (C greater than T greater than A greater than G). Esperamicin preferentially attacks at T and C bases in oligopyrimidine sequences such as 5'-CTC-3', 5'-TTC-3', and 5'-TTT-3'. In contrast to the preferred sites of cleavage by bleomycin, 5'-GT-3' and 5'-GC-3', the preferred sites of esperamicin-mediated DNA degradation are 5'-TG-3' and 5'-CG-3' sequences. The nucleotide-specific cleavage mode of esperamicin is significantly affected by pretreatment of DNA with netropsin and distamycin A, suggesting that interaction of esperamicin occurs through the minor groove of B-DNA. This is further supported by the asymmetric cleavage pattern to the 3' side on the opposite strand of the DNA. The roles of the fucose-anthranilate moiety and the trisaccharide side chain of esperamicin in DNA binding and base recognition are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burger R. M., Berkowitz A. R., Peisach J., Horwitz S. B. Origin of malondialdehyde from DNA degraded by Fe(II) x bleomycin. J Biol Chem. 1980 Dec 25;255(24):11832–11838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll M., Frederick C. A., Wang A. H., Rich A. A bifurcated hydrogen-bonded conformation in the d(A.T) base pairs of the DNA dodecamer d(CGCAAATTTGCG) and its complex with distamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Dec;84(23):8385–8389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea A. D., Haseltine W. A. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by the antitumor antibiotics neocarzinostatin and bleomycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta D., Goldberg I. H. Mode of reversible binding of neocarzinostatin chromophore to DNA: base sequence dependency of binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Jan 24;14(2):1089–1105. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.2.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edo K., Iseki S., Ishida N., Horie T., Kusano G., Nozoe S. An electron spin resonance study of a spin adduct of the non-protein component (NPC) of neocarzinostatin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980 Dec;33(12):1586–1589. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganther H. E. Reduction of the selenotrisulfide derivative of glutathione to a persulfide analog by glutathione reductase. Biochemistry. 1971 Oct 26;10(22):4089–4098. doi: 10.1021/bi00798a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg I. H. Novel types of DNA-sugar damage in neocarzinostatin cytotoxicity and mutagenesis. Basic Life Sci. 1986;38:231–244. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9462-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatayama T., Goldberg I. H., Takeshita M., Grollman A. P. Nucleotide specificity in DNA scission by neocarzinostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Aug;75(8):3603–3607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappen L. S., Ellenberger T. E., Goldberg I. H. Mechanism and base specificity of DNA Breakage in intact cells by neocarzinostatin. Biochemistry. 1987 Jan 27;26(2):384–390. doi: 10.1021/bi00376a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyoto S., Shibata T., Kawai Y., Hori Y., Nakayama O., Terano H., Kohsaka M., Aoki H., Imanaka H. New antitumor antibiotic, FR-900405. III. Mechanism of action of FR-900405. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1985 Jul;38(7):955–956. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide Y., Ito A., Edo K., Ishida N. The biologically active site of neocarzinostatin-chromophore. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1986 Oct;34(10):4425–4428. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.4425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara J., Sugiura Y. Sequence-specific recognition and cleavage of DNA by metallobleomycin: minor groove binding and possible interaction mode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Apr;85(8):2459–2463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Goldberg I. H. Sequence-specific, strand-selective, and directional binding of neocarzinostatin chromophore to oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Biochemistry. 1989 Feb 7;28(3):1019–1026. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long B. H., Golik J., Forenza S., Ward B., Rehfuss R., Dabrowiak J. C., Catino J. J., Musial S. T., Brookshire K. W., Doyle T. W. Esperamicins, a class of potent antitumor antibiotics: mechanism of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(1):2–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey V., Williams C. H., Jr, Palmer G. The presence of S degrees-containing impurities in commercial samples of oxidized glutathione and their catalytic effect on the reduction of cytochrome c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971 Feb 19;42(4):730–738. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClarin J. A., Frederick C. A., Wang B. C., Greene P., Boyer H. W., Grable J., Rosenberg J. M. Structure of the DNA-Eco RI endonuclease recognition complex at 3 A resolution. Science. 1986 Dec 19;234(4783):1526–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.3024321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura Y., Suzuki T. Nucleotide sequence specificity of DNA cleavage by iron-bleomycin. Alteration on ethidium bromide-, actinomycin-, and distamycin-intercalated DNA. J Biol Chem. 1982 Sep 25;257(18):10544–10546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takusagawa F., Dabrow M., Neidle S., Berman H. M. The structure of a pseudo intercalated complex between actinomycin and the DNA binding sequence d(GpC). Nature. 1982 Apr 1;296(5856):466–469. doi: 10.1038/296466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zein N., Sinha A. M., McGahren W. J., Ellestad G. A. Calicheamicin gamma 1I: an antitumor antibiotic that cleaves double-stranded DNA site specifically. Science. 1988 May 27;240(4856):1198–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.3240341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]